What Europeans really want: Five myths debunked

Summary

- The 2019 European Parliament election will be radically different from the tales in the headlines: it will not be a referendum on migration.

- New ECFR/YouGov research reveals huge fluidity in current voting intentions: 70 percent of Europeans certain to vote are yet to make their choice. Nearly 100m swing voters are up for grabs.

- The big divide is not ‘open Europe’ versus ‘closed nation states’ but between status quo and change. Record numbers of people now support the EU – and even Eurosceptic parties have repositioned themselves.

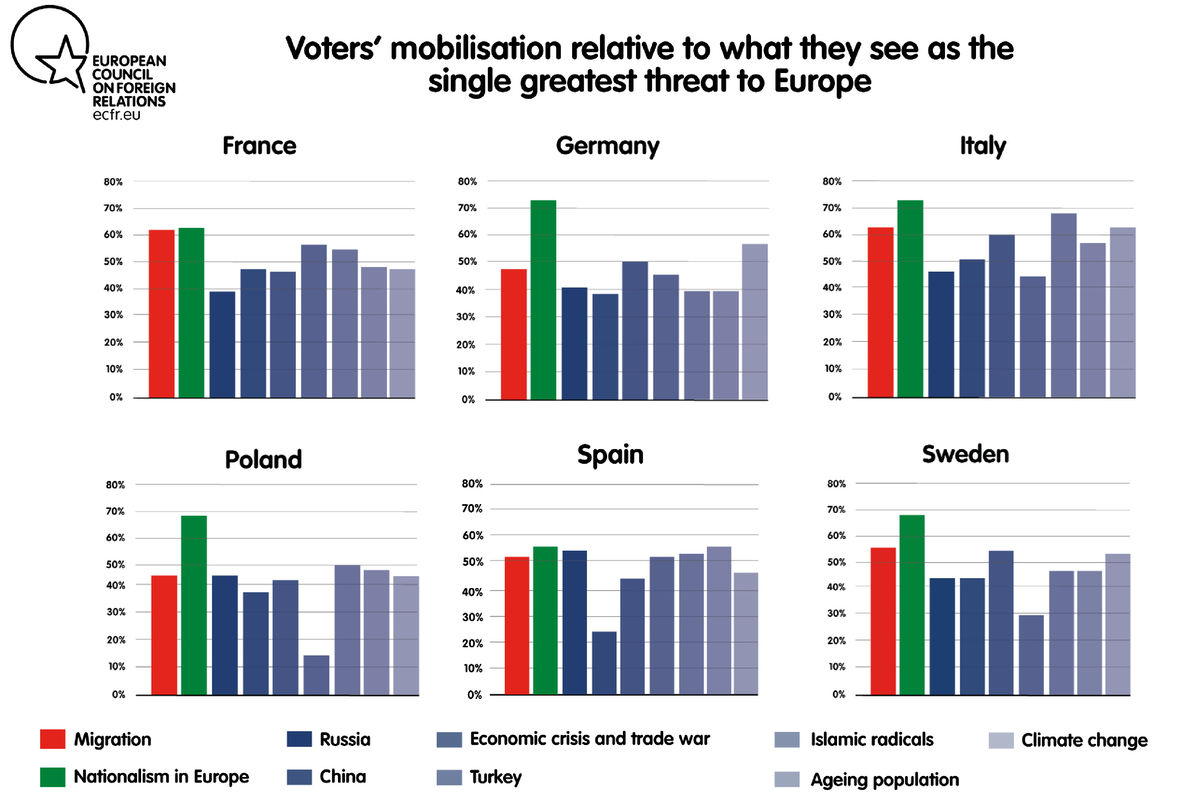

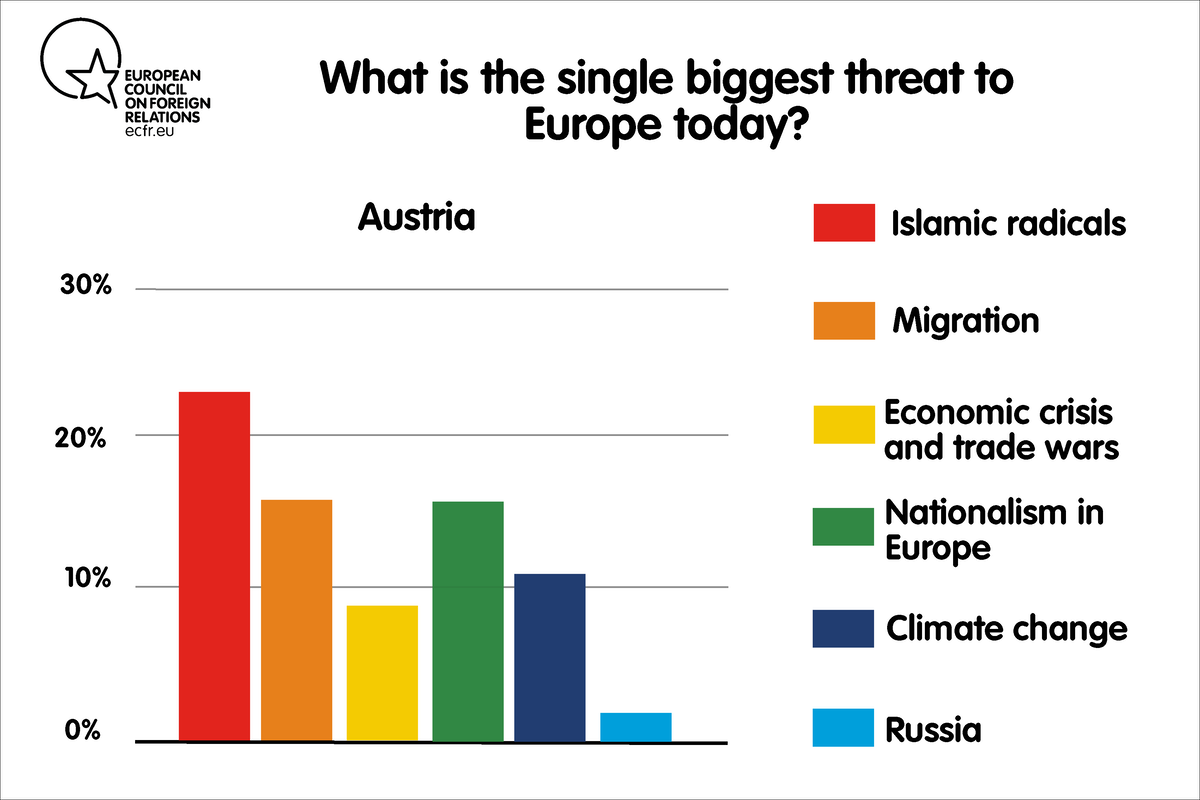

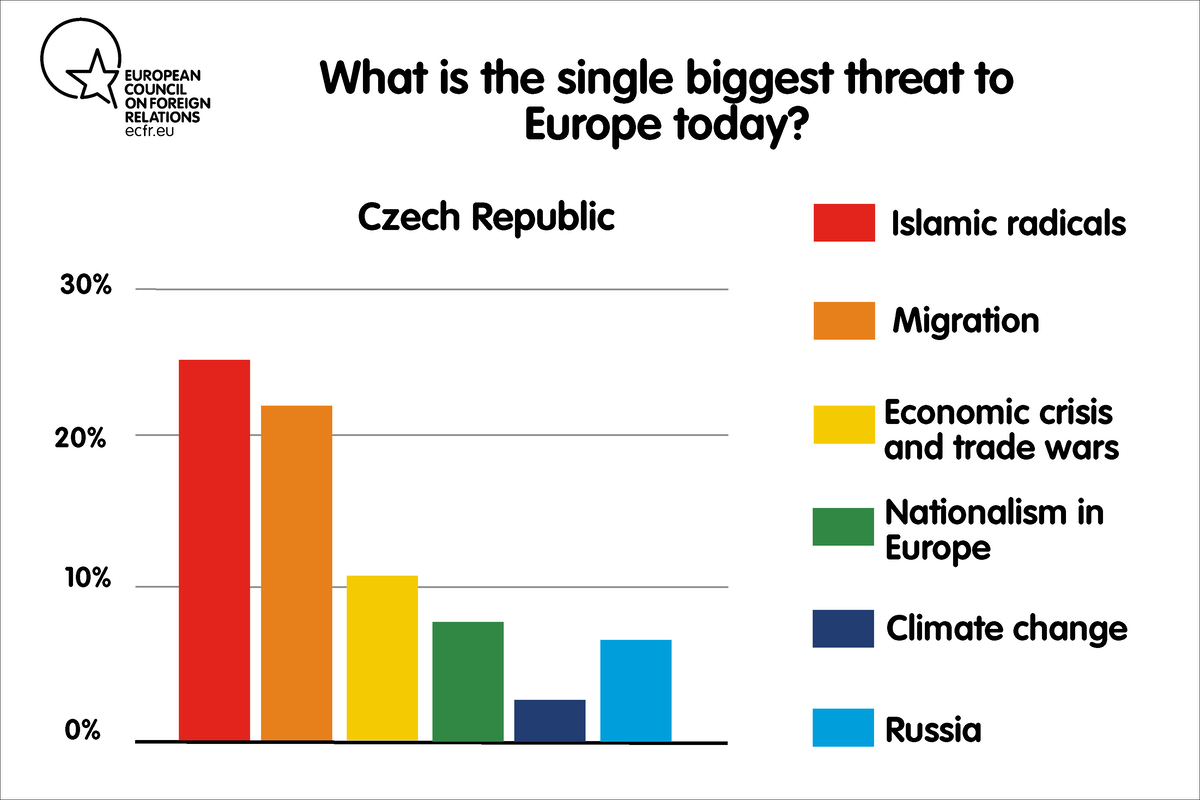

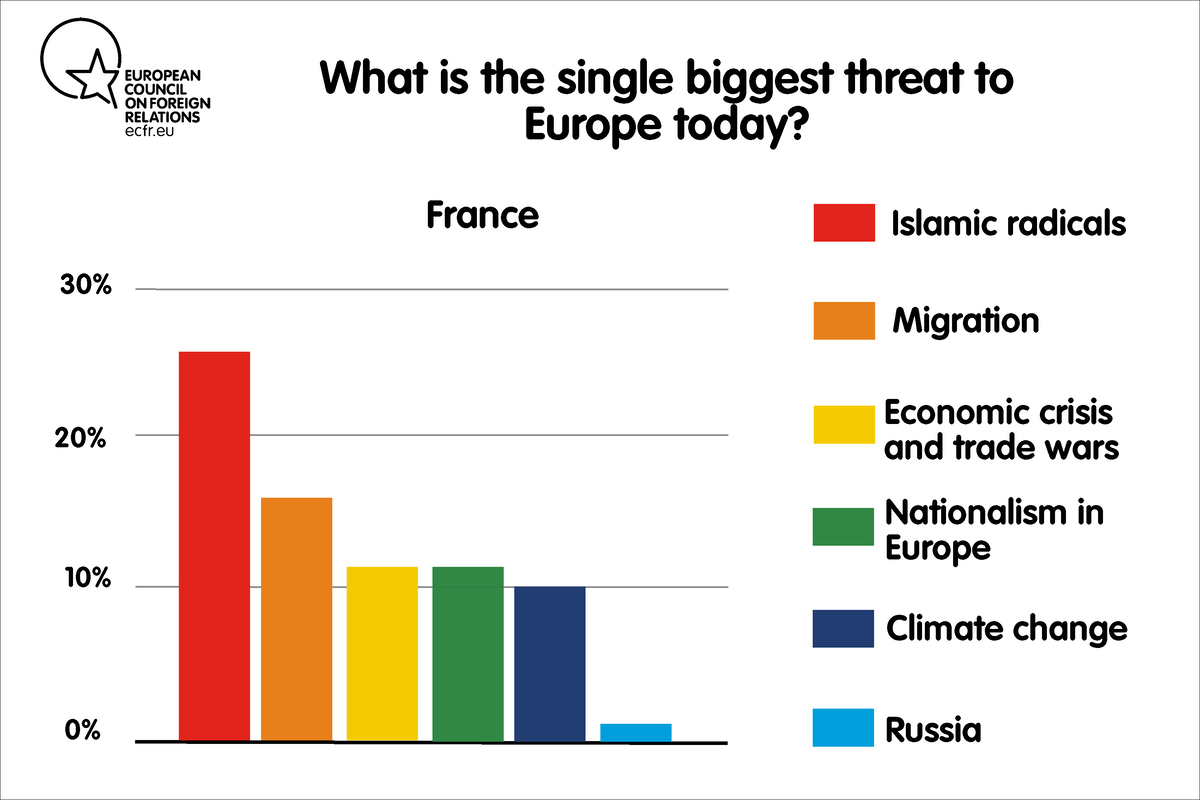

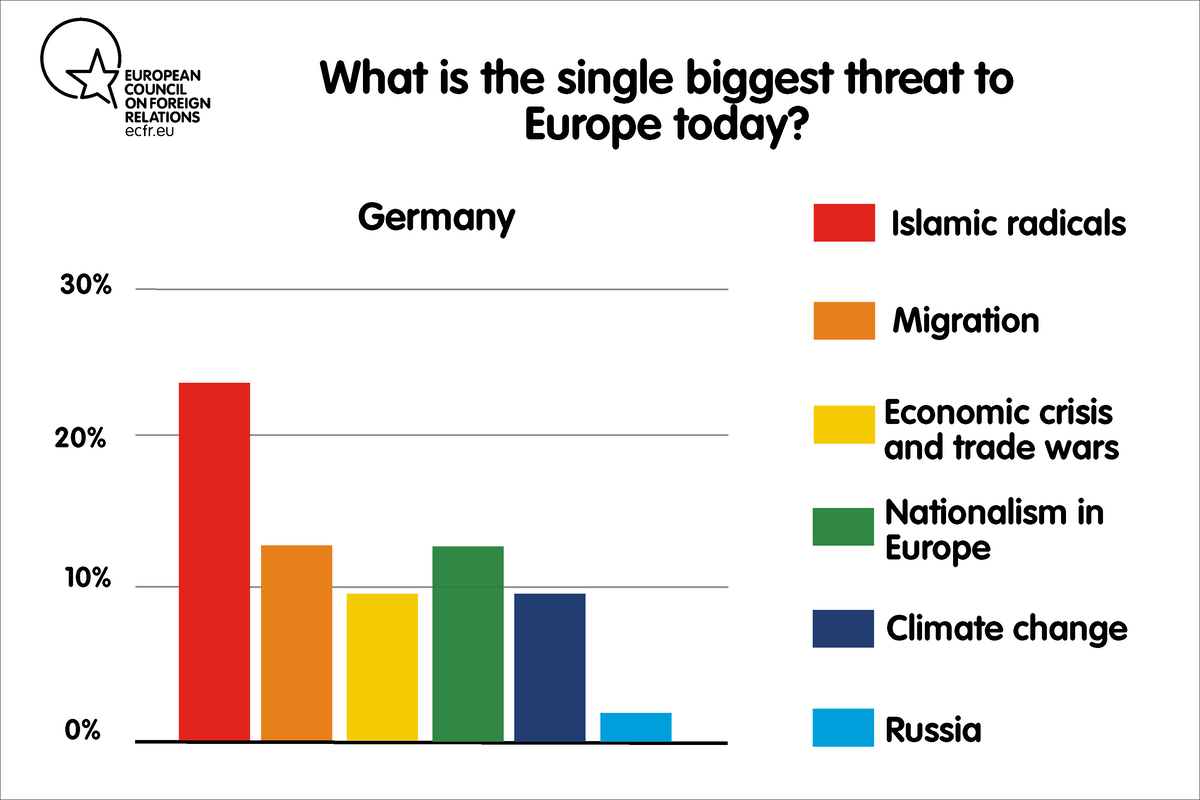

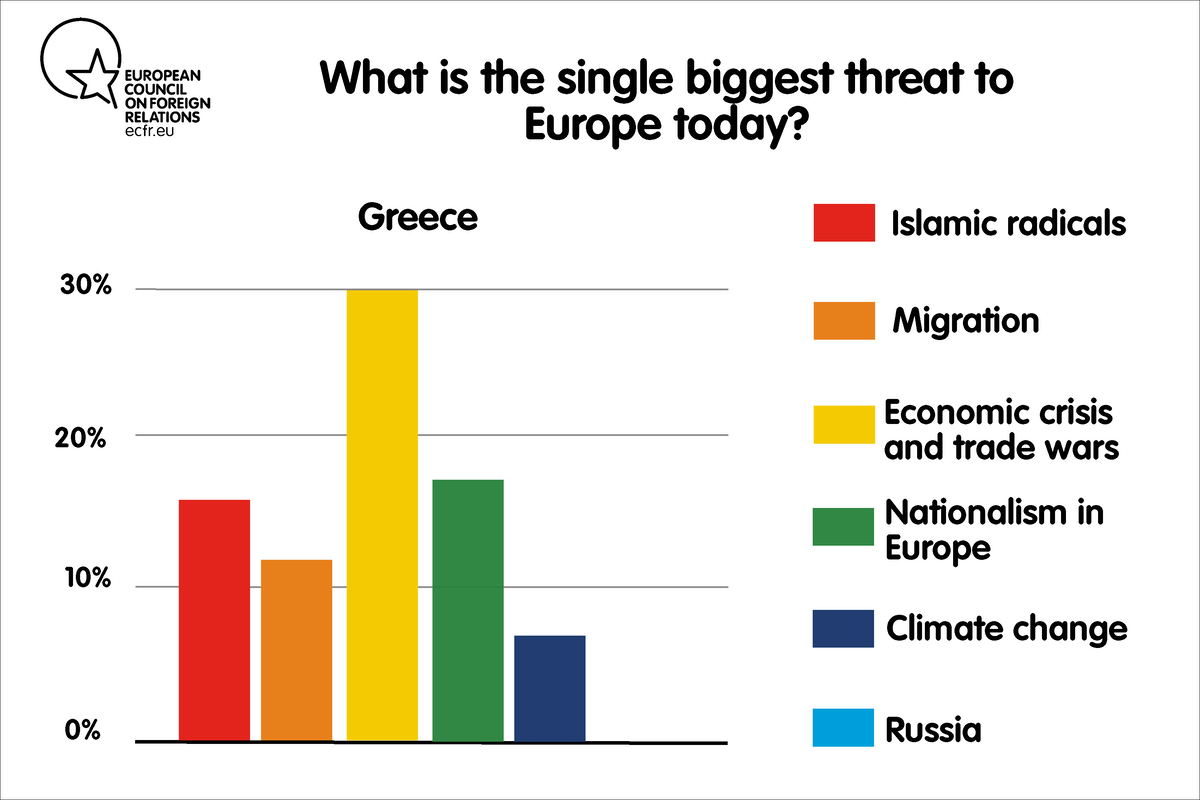

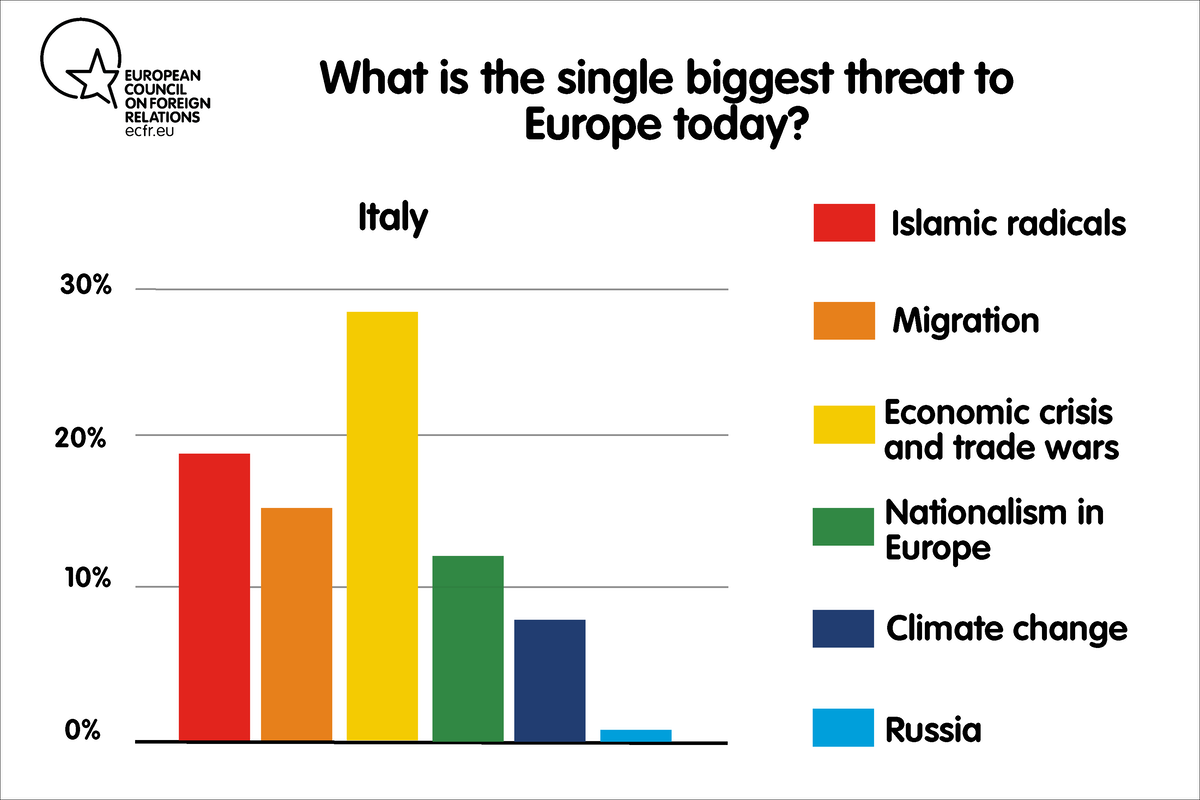

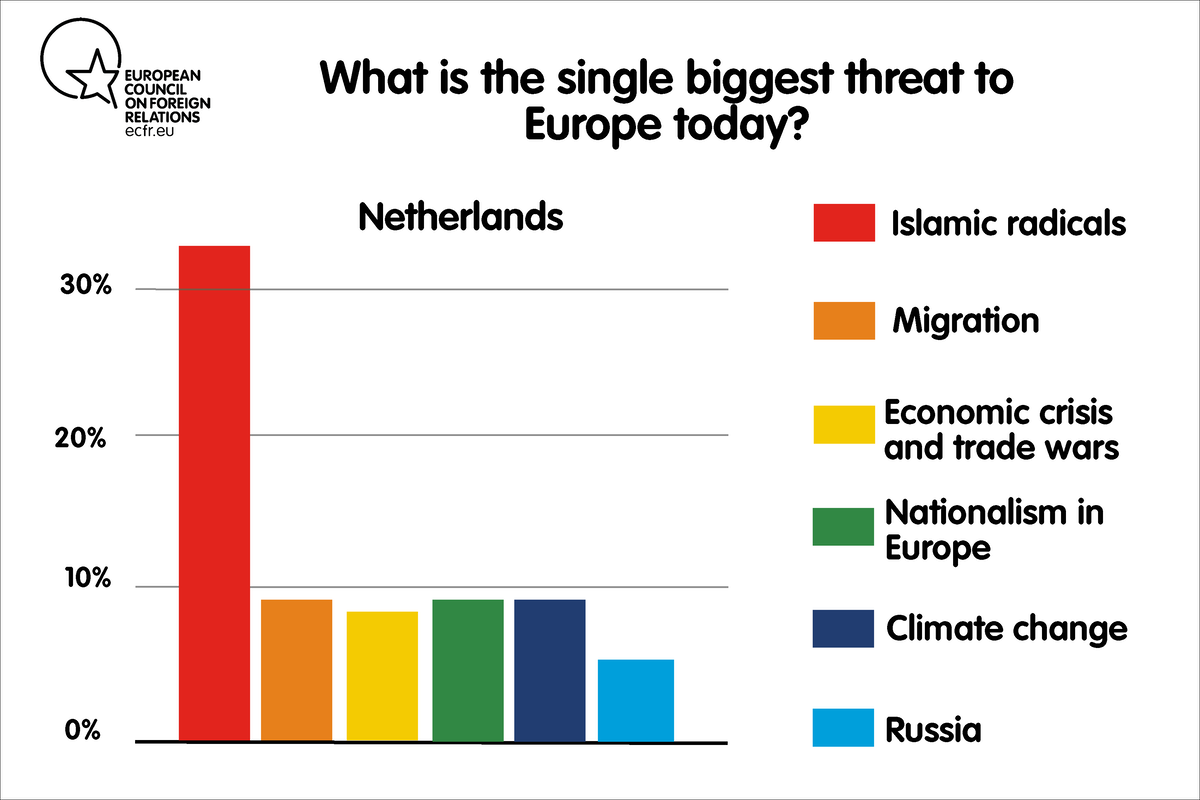

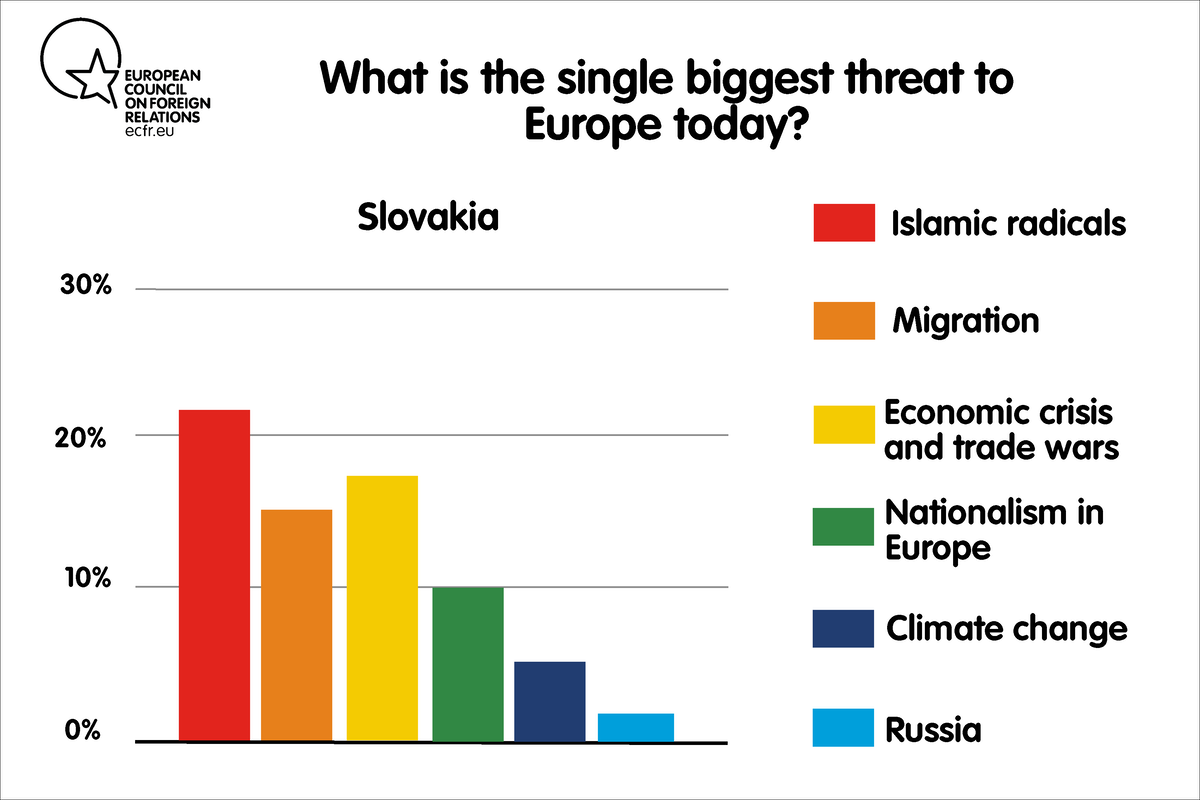

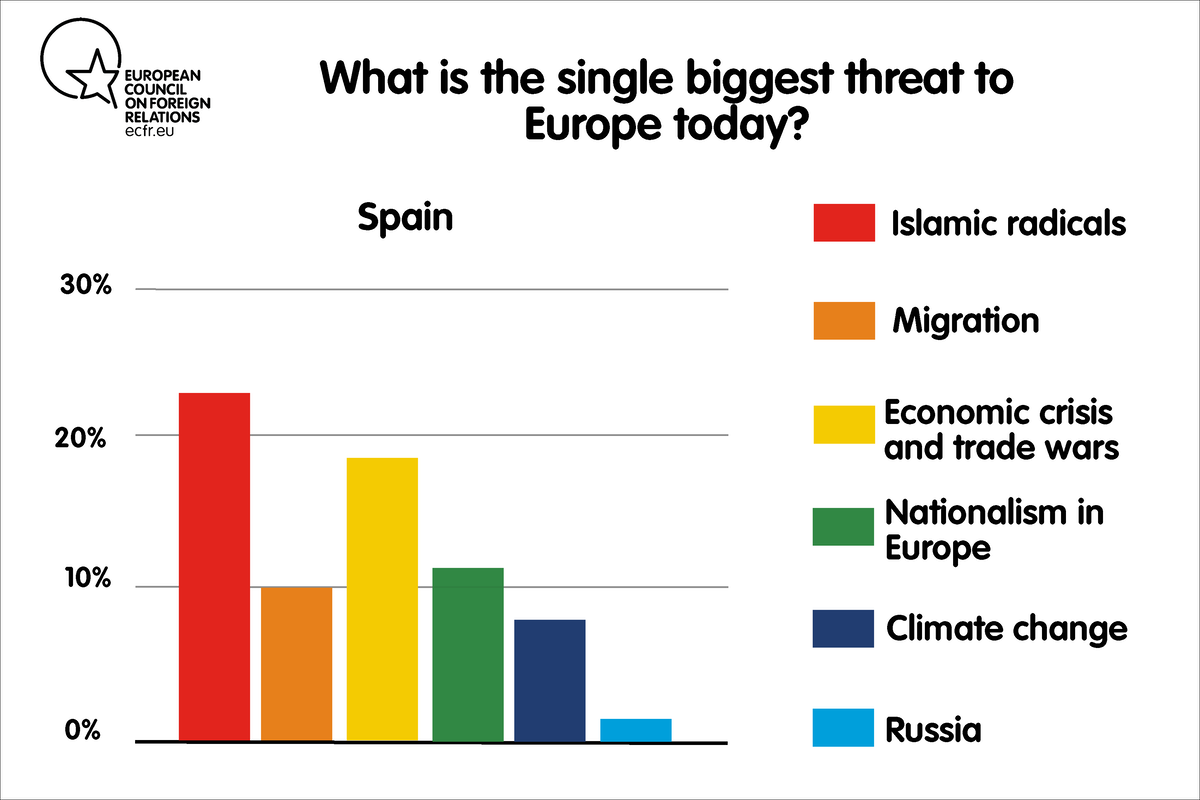

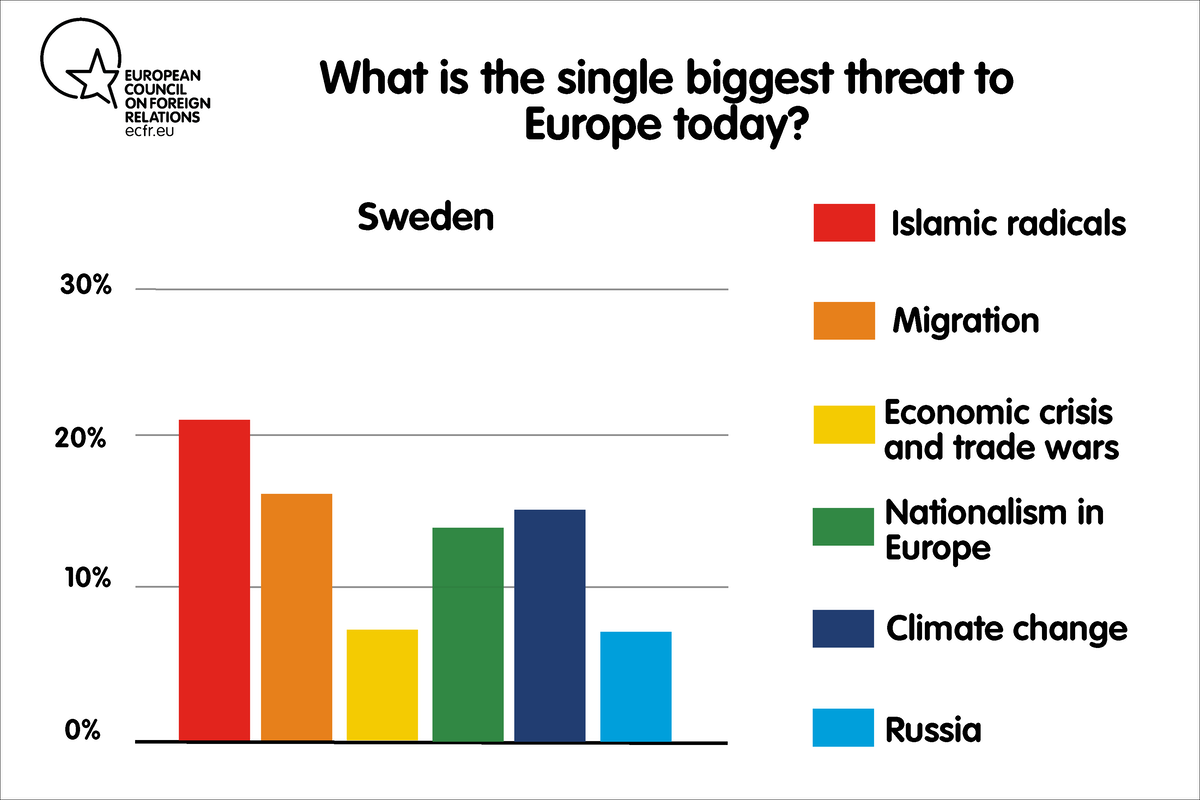

- There is no single issue on voters’ minds; indeed, many are more worried about emigration than immigration, and many are concerned about: Islamic radicalism (87m, 22 percent of the EU voting population); the rise of nationalism (45m, 11 percent); and the economy (63m, 16 percent). Just under 59m highlight migration as one of the top threats to Europe: only 15 percent of the EU voting population.

- These findings shed light on the issues that will decide Europeans’ votes and the battlegrounds that moderate mainstream politics can engage them on. Crucially, voters right now are ready to move in many different directions – so even last-minute events could shape the final make-up of the European Parliament.

Introduction

“Populists are whipping up a storm as Europe faces lurch to the right”; “Explained: the rise and rise of populism in Europe”. Headlines about the European Parliament election in May scream that 2019 is set to be Act Three in the Donald Trump and Brexit drama, this time across the European Union. They warn of a grand showdown between those who believe in an open Europe and those who believe in closed national societies, with migration as the key mobilising issue.

But are the headline-writers correct? Is this really what is brewing? New research by the European Council on Foreign Relations and YouGov suggests not.

It is true that the last decade has seen a splintering of national party systems across the EU. Anti-system parties have grown in strength at almost every national election, campaigning on the promise to give voice to those the current system does not represent. Nine governments in Europe now include anti-European parties. And, after the forthcoming European Parliament election, at least one-third of parliamentarians are projected to come from anti-European parties. Were they to form a single bloc, they would be the largest in the parliament and would easily outnumber either the Christian Democrat European People’s Party or the Socialists & Democrats group.

It is often said that generals are always preparing to fight the last war. As Europe’s political parties kick off their campaigns for the European Parliament election, it does indeed appear that their strategies are informed by lessons learned from recent votes they have observed. Brexit, Trump, Viktor Orban, and Emmanuel Macron have coloured their expectations and those of the elite more generally. As a result, five highly misleading ideas about the shape of European politics are defining the debate.

This first is that this election represents a descent into tribal politics: that continental European politics, as with those in the United Kingdom and the United States, have shifted in the past four years from parties to tribes. The second myth is that the old left-right divide is giving way to a split between pro-Europeans and nationalists – between advocates of an open or closed Europe. Macron’s experience in the second round of the French presidential election has contributed to the emergence of this myth. Thirdly, the continuing strength of Orban has engendered the idea that the European Parliament election will be a referendum on migration, resulting in offers from politicians to build more walls. Orban is also responsible for the fourth myth – of a growing split between an illiberal, anti-migration eastern Europe and a western Europe that supports EU values. Finally, there is a lingering myth that the vote is bound to be a predominantly national, low-turnout affair that has no transnational or pan-European aspects.

The noisy arrival to Europe of the Movement – an international alliance of Eurosceptic parties coordinated by former US presidential adviser Steve Bannon – fostered the idea of a European staging of the Trumpian revolution. Anti-European parties hail this; pro-European parties are mobilising to counter it.

But a large-scale opinion survey from ECFR and YouGov demonstrates that all these assumptions are wrong. Politicians who fight the European Parliament election based on these myths are likely to fail. The survey shows that voters are not seeking change from the far left or the far right – but they are seeking change. Mainstream parties can and should adapt, urgently, to address voters’ concerns. But, to do so successfully, they need to understand what these concerns really are – not what they imagine them to be.

Myth 1: Europe’s politics are becoming tribal

The truth: 97 million voters are up for grabs

Recent political events in the US and UK have heightened the fear that people are flowing away from mainstream parties based on class and towards new tribes based on identity. In the US, tribal divides between red and blue voters have been shaped by a “big sort” that involves people moving into parallel worlds that pray, work, marry, only with people like themselves. 1These groups are divided not just by their views – they have access to different facts that are produced by the partisan media outlets they rely upon for information.

In the UK, following the Brexit referendum, the left-right party split is less important for many people than some of the tribal divisions over Brexit that split north from south, young from old, towns from cities, and, above all, graduates from non-graduates. As in the US, these geographic and demographic differences are reinforced by culture: support for the death penalty has been identified as the best single indicator of whether UK citizens are pro-Brexit.

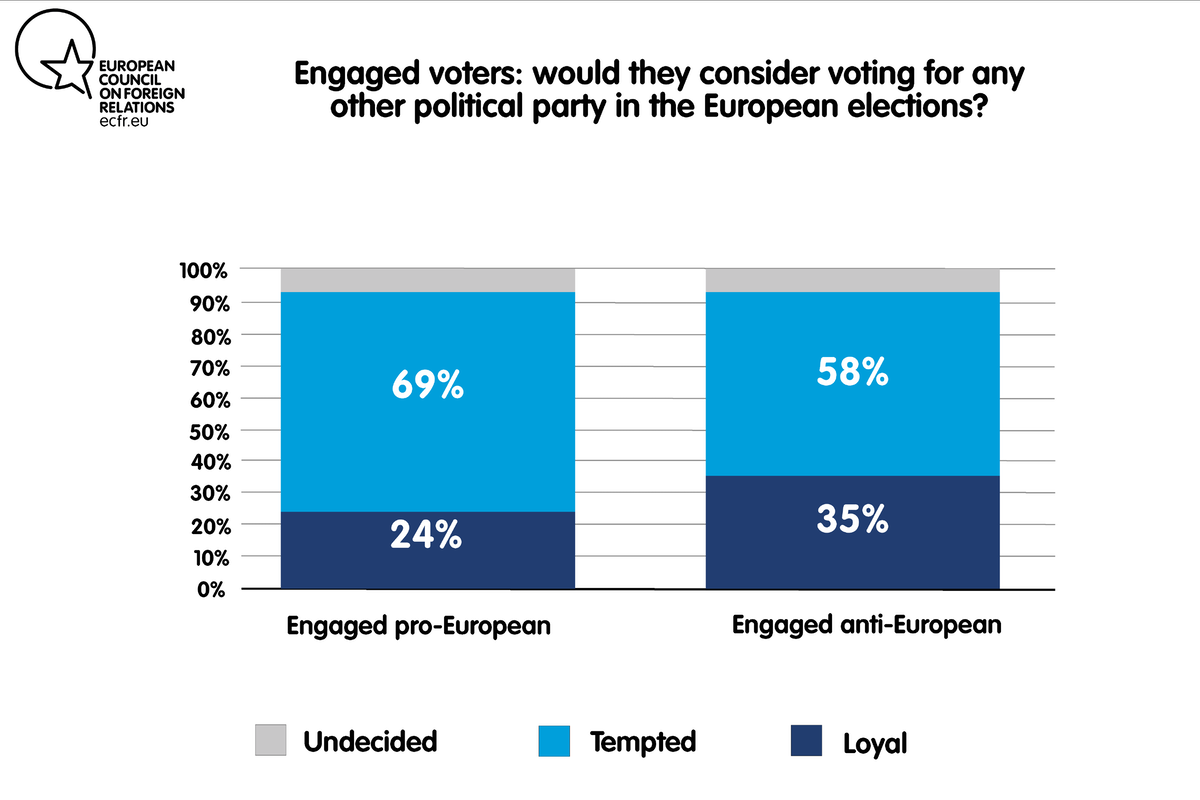

It would be easy to assume that these trends will now shape politics across Europe. So, after all the talk of tribes in the US and UK, we set out to identify the tribes of Europe. Our findings show that, while European societies are currently a complex and shifting whirlpool, they are not yet tribal. The research demonstrates that none of the classic indicators that have defined tribes in recent elections and votes in the US and the UK – geography, age, level of education, left and right, and religion – help much in predicting how people are planning to vote in the upcoming European Parliament election. In fact, the ECFR/YouGov poll reveals that the defining feature of the political landscape is volatility: voters have not yet made up their minds.2 And there are no fewer than 97 million of these confused and undecided voters.

The poll shows that only 43 percent of voters will definitely vote. The other 57 percent are less likely to turn out in the European Parliament election. So far, so unsurprising. Equally, between 15-30 percent of all electors do not have any preference yet; and between 30-50 percent of these undecideds will probably vote.

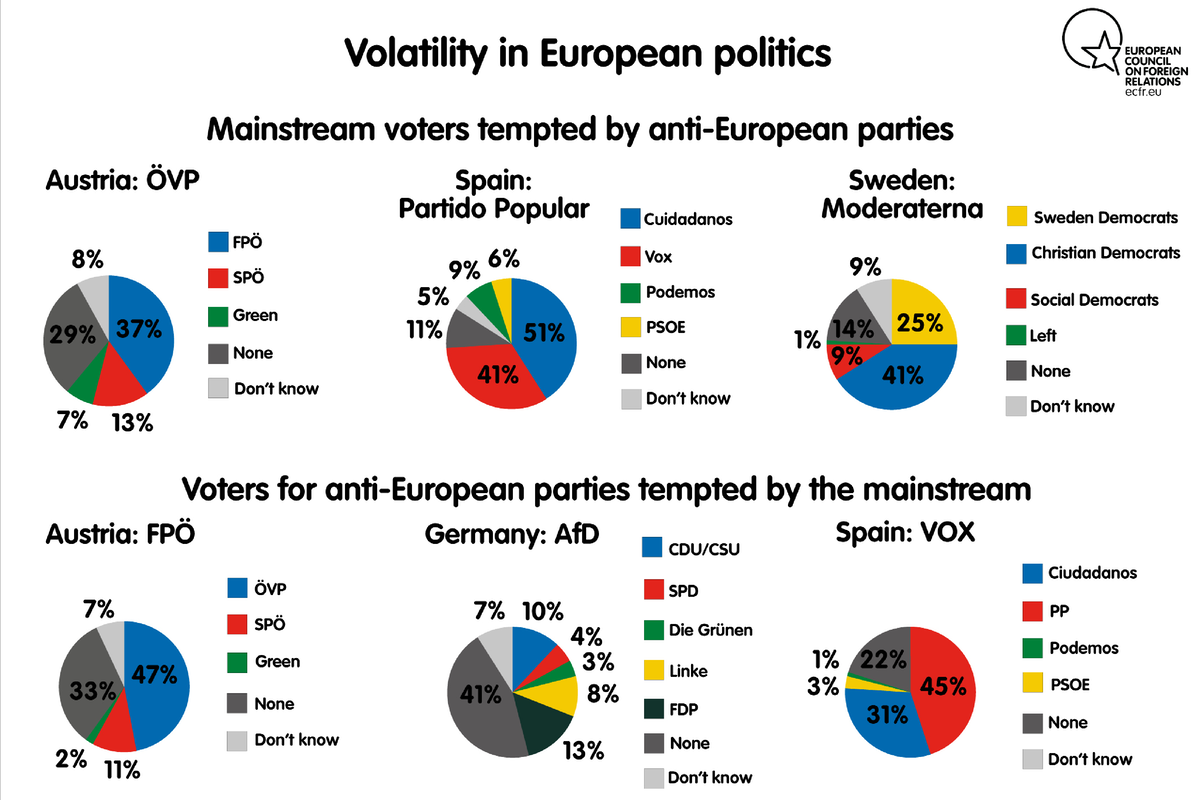

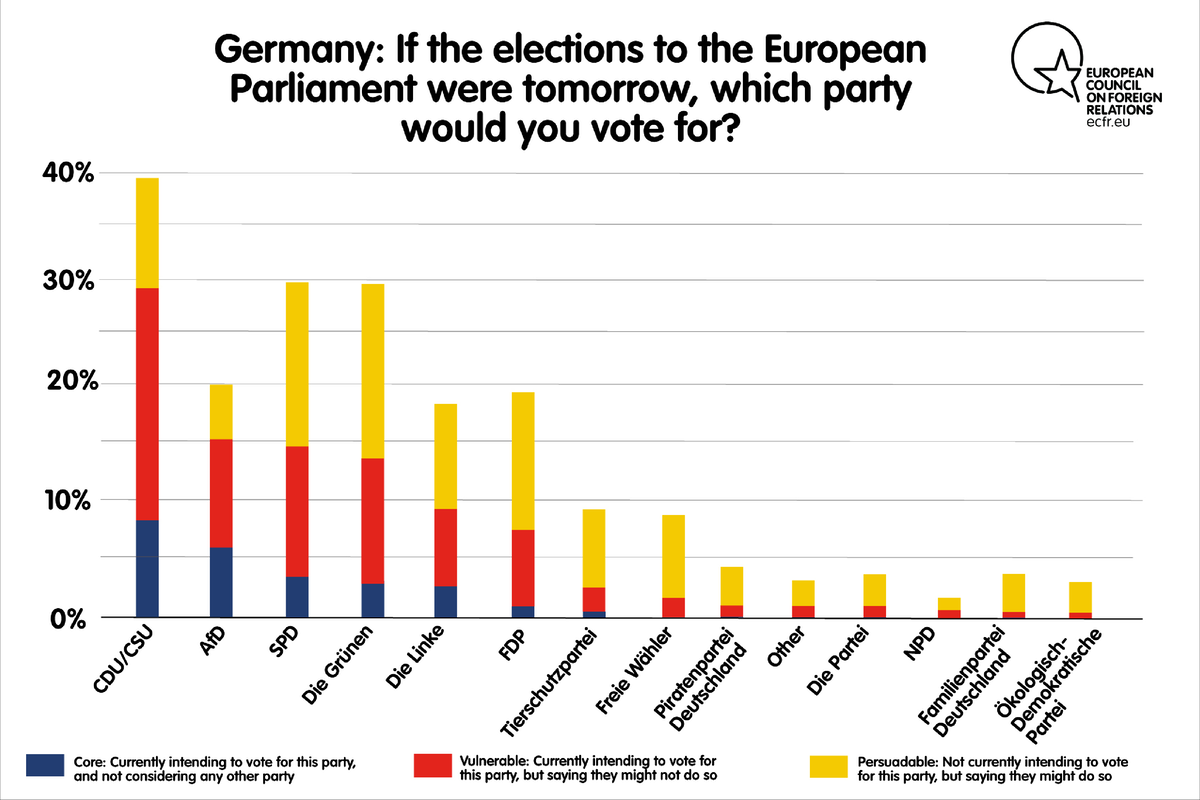

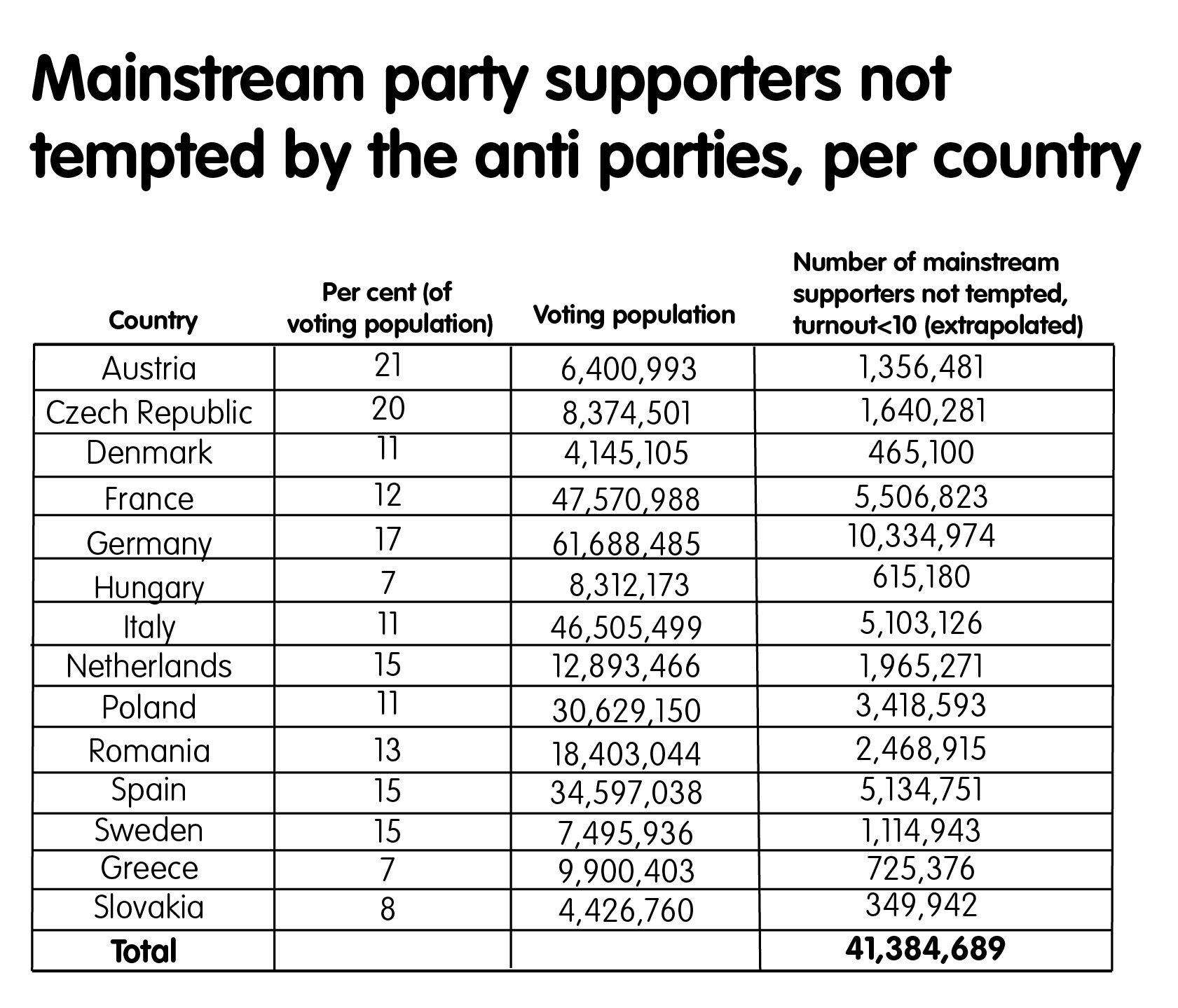

But 70 percent of those who have a voting preference are swing voters who have not decided on their choice: they say they might switch to another party – and it is these people who make up the 97 million. Among those who are planning to turn out in countries such as Denmark, France, Germany, and Hungary, 6-7 percent of mainstream party voters are tempted by an anti-European party. In Greece, this is as high as 9 percent. Even venerable parties such as the Christian Democratic Union and the Social Democratic Party in Germany can only count on 8.6 percent and 3.4 percent of German voters respectively as a solid base. And this plays both ways: 6 percent of anti-European voters across Europe are tempted by the mainstream. Electoral movement is thus not just in one direction, but in all directions among the very same people.

Political analyst Gilles Finchelstein has explored how politics have shifted in France, from a situation in which clearly organised political parties represented social structures to one that reflected the realities of the post-cold war period.3 In that period, politics became “liquid”, as society itself became more complex and a growing group of voters turned into swing voters, switching their support between mainstream parties in elections. However, politics today have now gone a stage further and entered the “gaseous era”, according to Finchelstein. It is a shapeless agglomeration of unpredictable, atomised units that can come together momentarily to form compounds before disappearing once again into the ether. As in other gaseous conditions, it can be toxic or explosive and is very difficult for parties and leaders to get under control.

Our research shows that, in this gaseous era of politics, the usual rules for predicting how voters are likely to behave no longer apply. Whereas vote choice and turnout are usually analysed as a function of socio-demographic factors, the upcoming election is driven more by issues. The probability of turning out in the election depends on what issues you care about, and there is also strong evidence for issue-based voting. But it is not only the position that leaders take on issues that matters; it is also their leadership and personalities, and the trust that people have in them. In other words: do leaders appear to embody the values and feelings of voters? Simply put, the rules of the election game have evolved.

Myth 2: The European election will be a clash between those who believe in (open) Europe and those who believe in the (closed) nation state

The truth: What matters is for parties to be agents of change

The EU risks slipping into a populist-nationalist “nightmare” unless centrists win greater public backing for the European cause: such was the warning issued by the leader of the European Parliament liberal group, Guy Verhofstadt. This is the mirror image of what the far right have argued as they portray the elections as a battle between globalists and nationalists. On either side, pro-Europeans and anti-Europeans mount strikingly similar arguments.

The contest that pitted the pro-European Macron against Marine Le Pen, the anti-European leader of Rassemblement National, in the second round of the French presidential election has contributed to this sentiment. In an electrifying debate ahead of that poll, Macron broke with the timidity of pro-Europeans and directly challenged Le Pen on her severe Euroscepticism and her advocacy of France quitting the euro. This put the National Front leader on the back foot. Macron’s camp sees that confrontation as the critical moment when his victory became certain.

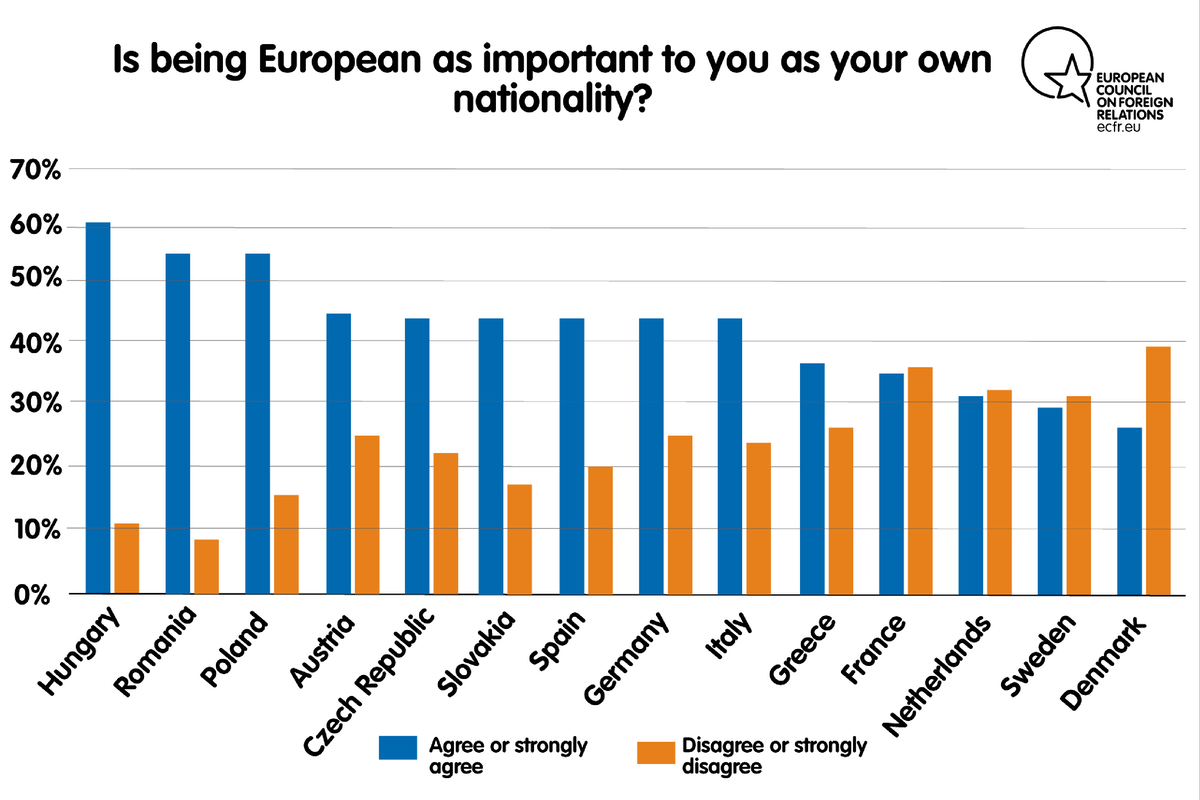

But the ECFR/YouGov poll shows that the core divide in EU countries will not be one that pits supporters of the EU against nationalists. Instead, for the majority of citizens, this is not a choice they feel the need to make: for them, being European is as important as their national identity. Only 25 percent of respondents disagreed with the statement that their European identity is as important to them as their national identity. Further analysis is needed to dig into the extent to which this identification is with the European project or is rooted in an ethno-religious definition of being European. But it shows that most EU citizens believe European and national identities to be complementary rather than in conflict.

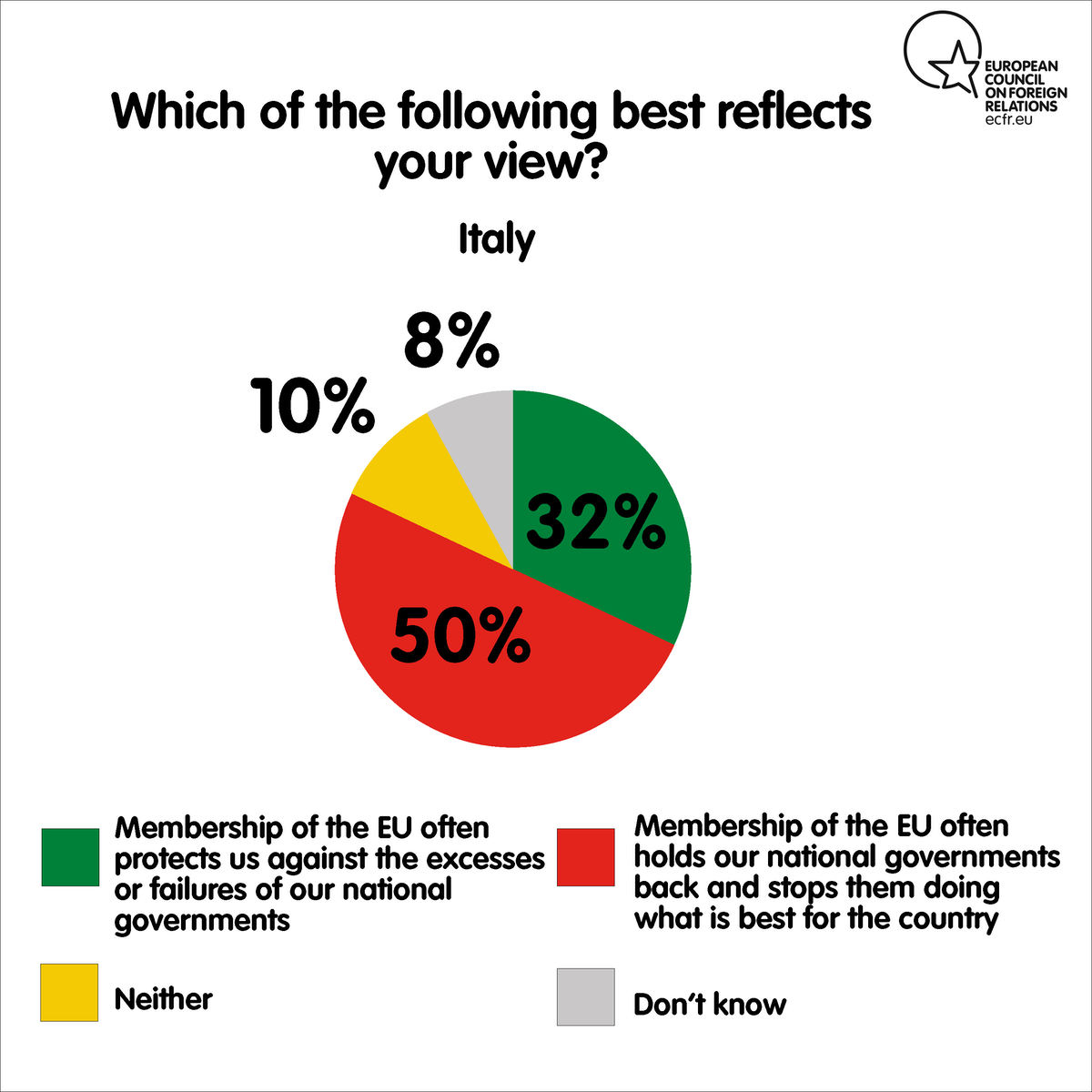

Nationalist parties have learned this lesson as well. In the last few months, most of them have tried to reposition themselves on Europe and abandoned their previously expressed desire to take their countries out of the euro. This is not just true of the Rassemblement National but also of the League and the Five Star Movement in Italy. Their goal is not to appear anti-European but rather to offer a refoundation of Europe – one that will allow countries to resist migration and reclaim sovereignty from the institutions in Brussels. It allows them to avoid alienating the pro-European majority, but at the same time to portray themselves as champions of change rather than nostalgic defenders of the status quo.

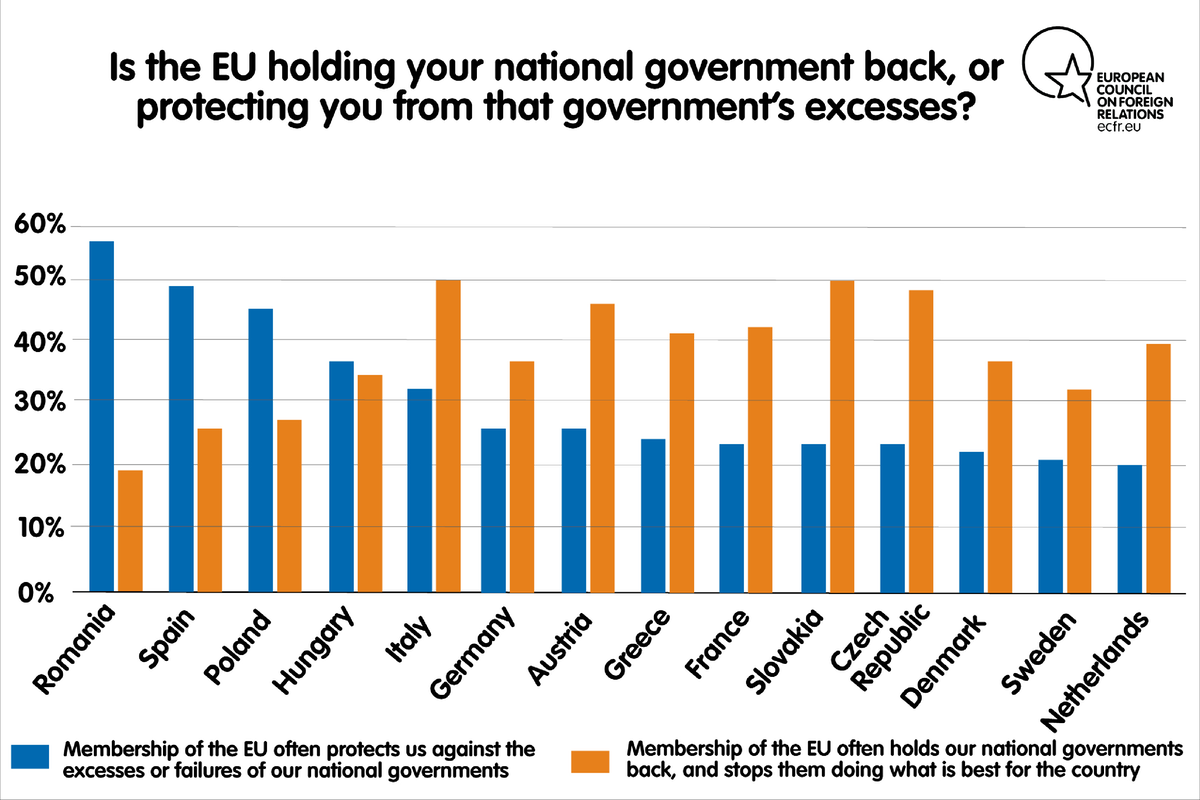

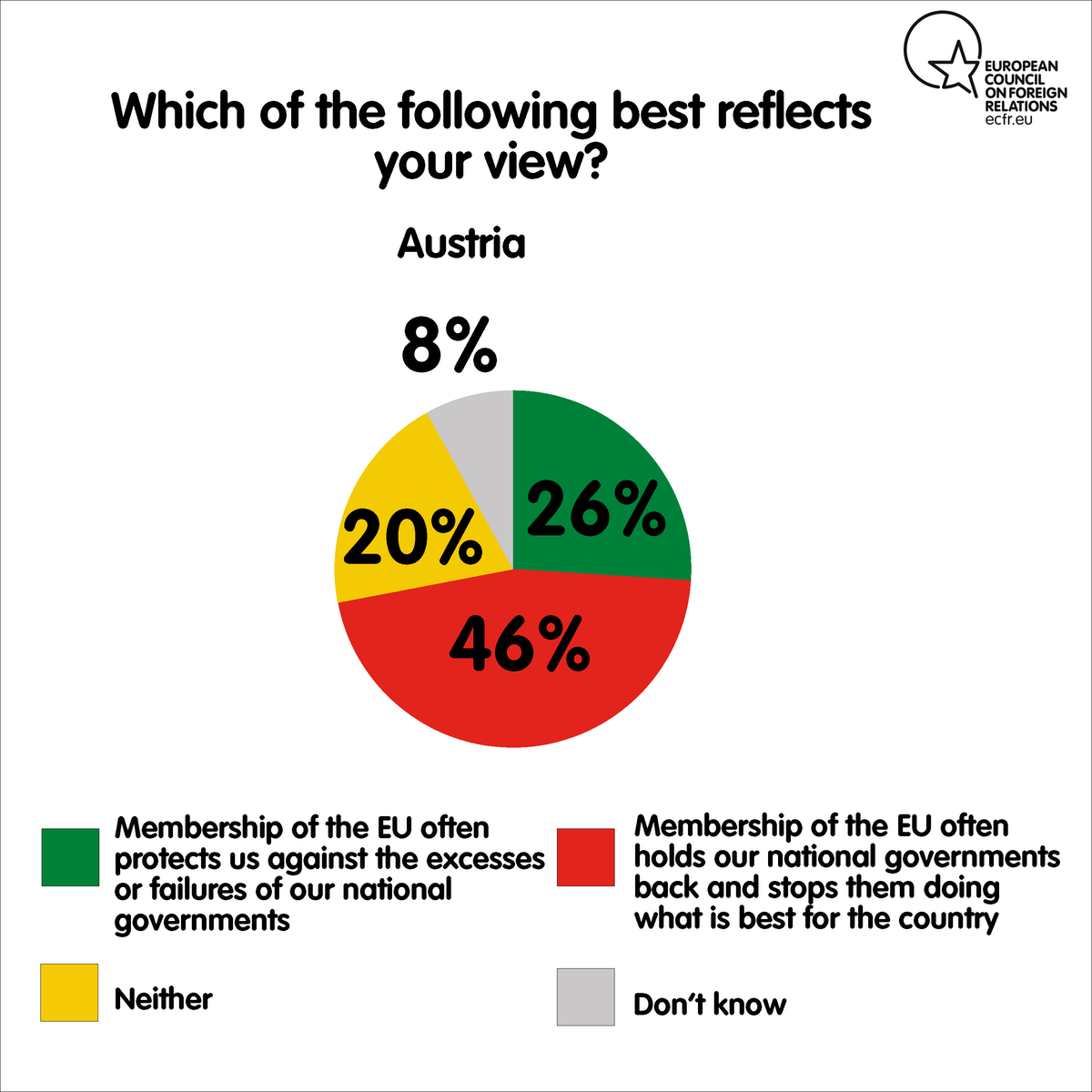

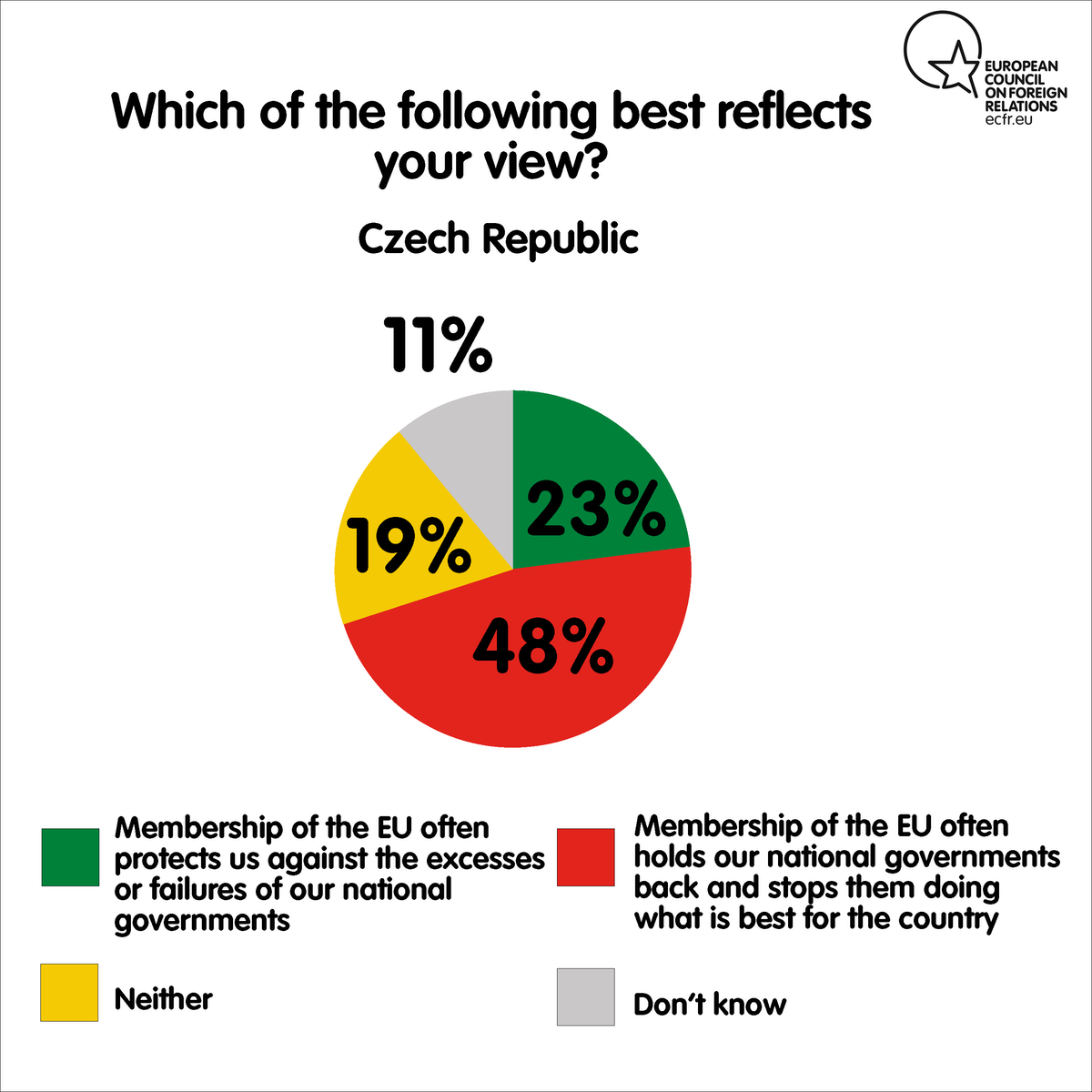

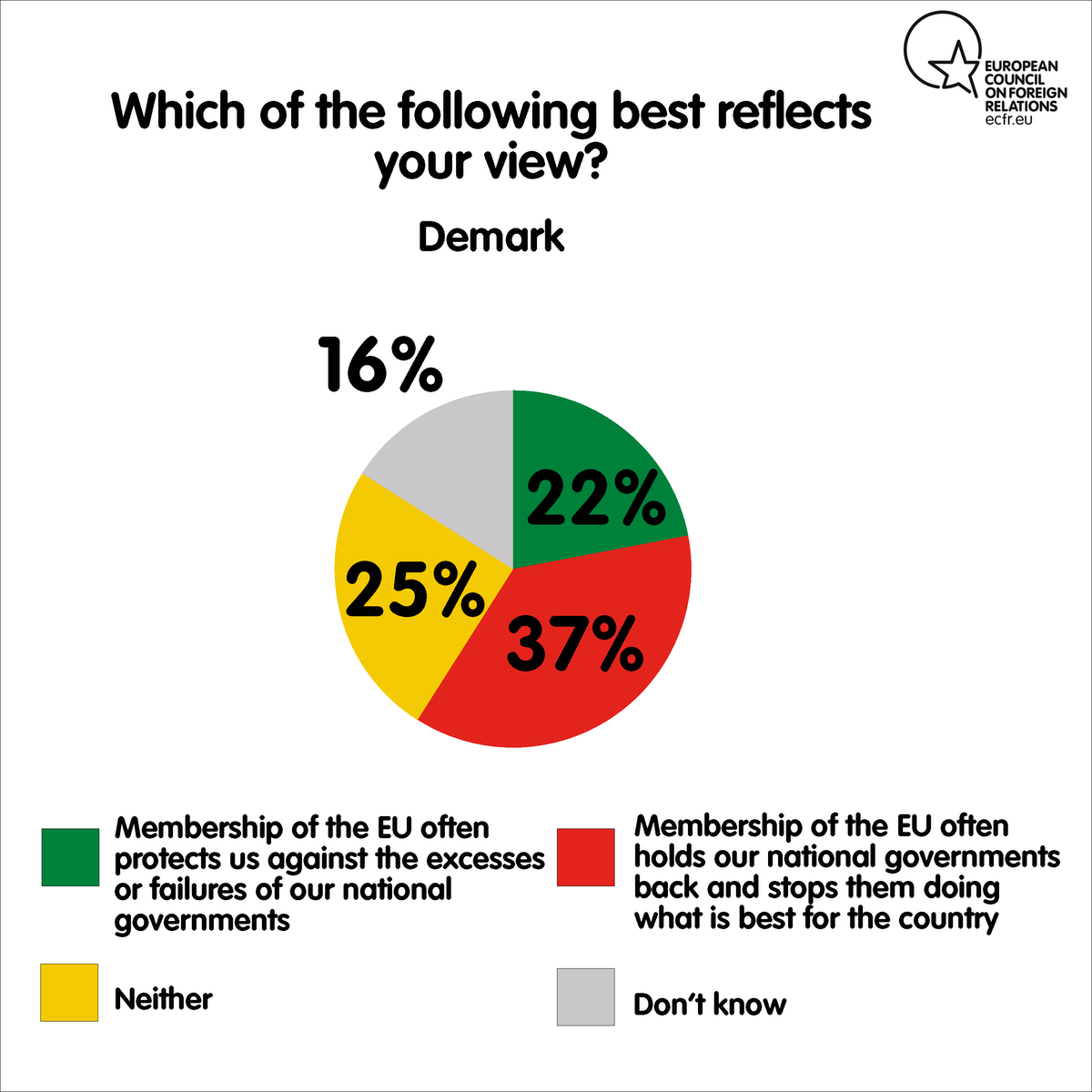

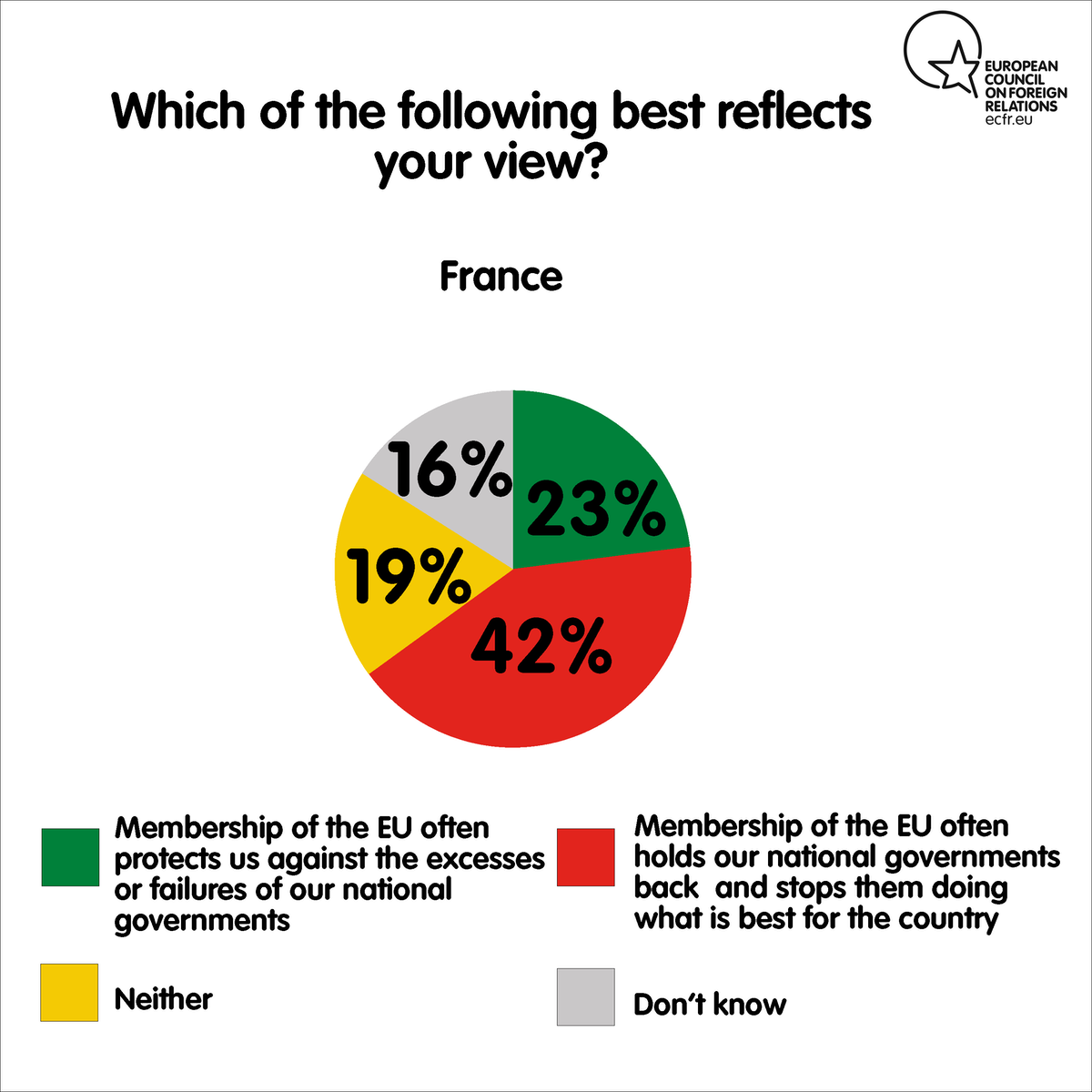

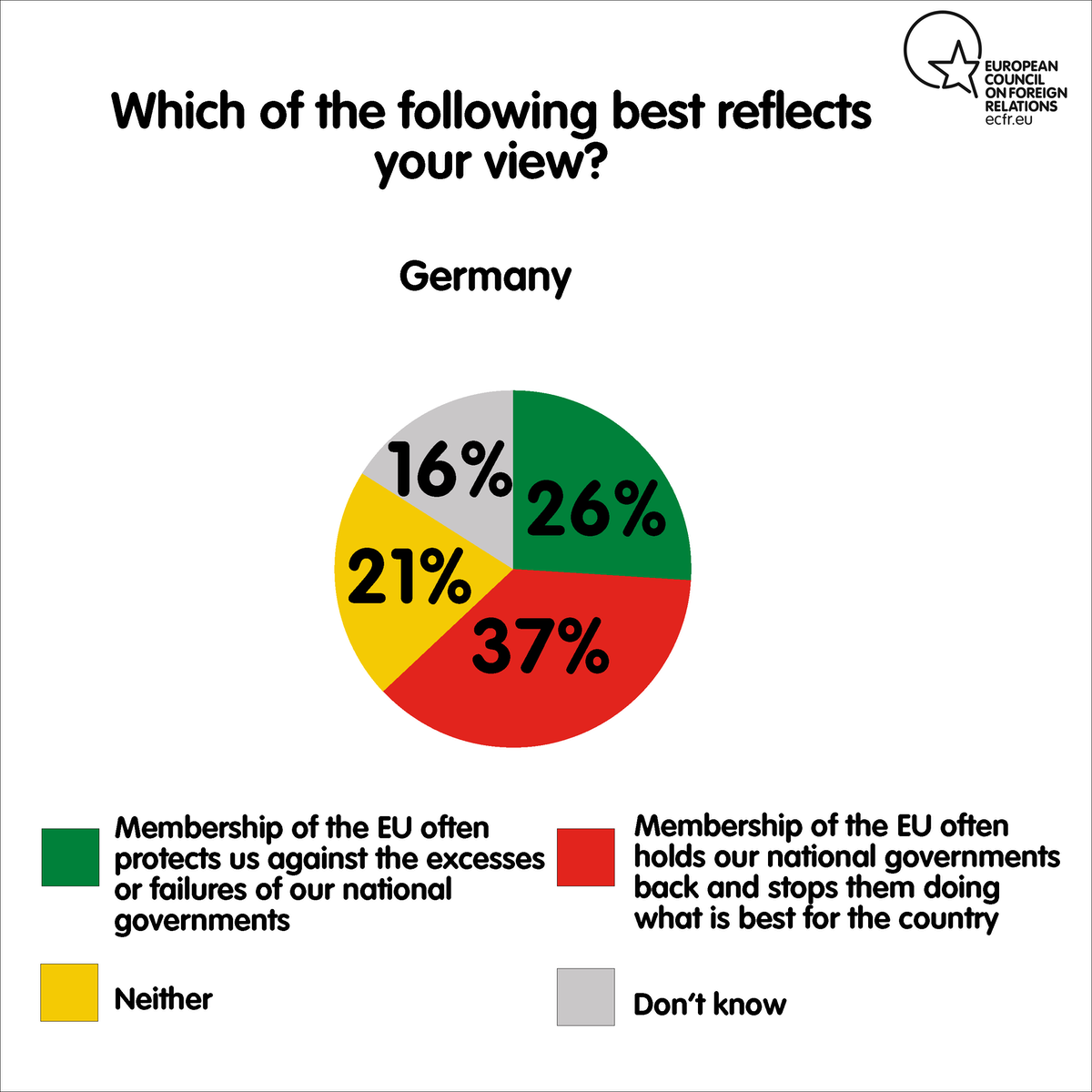

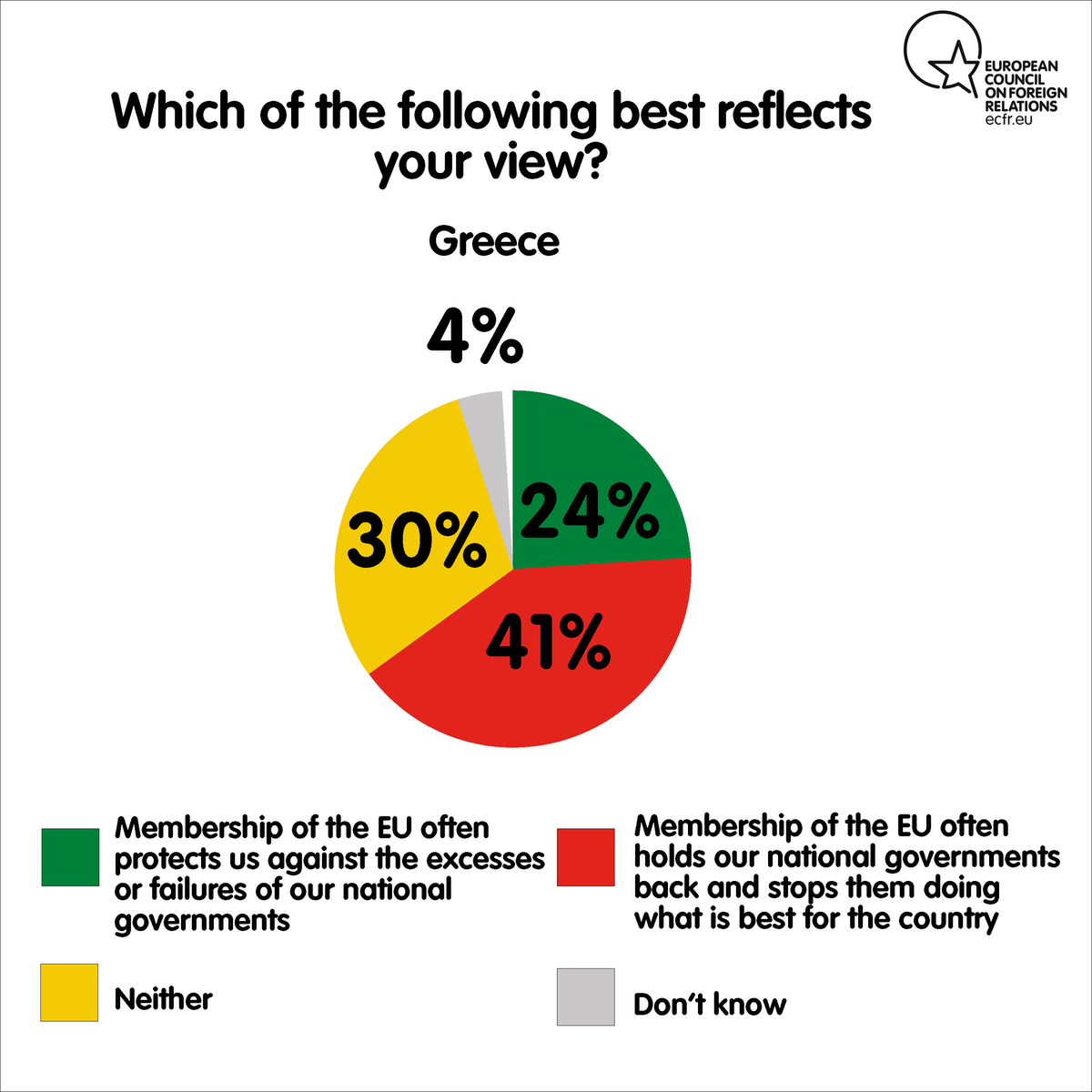

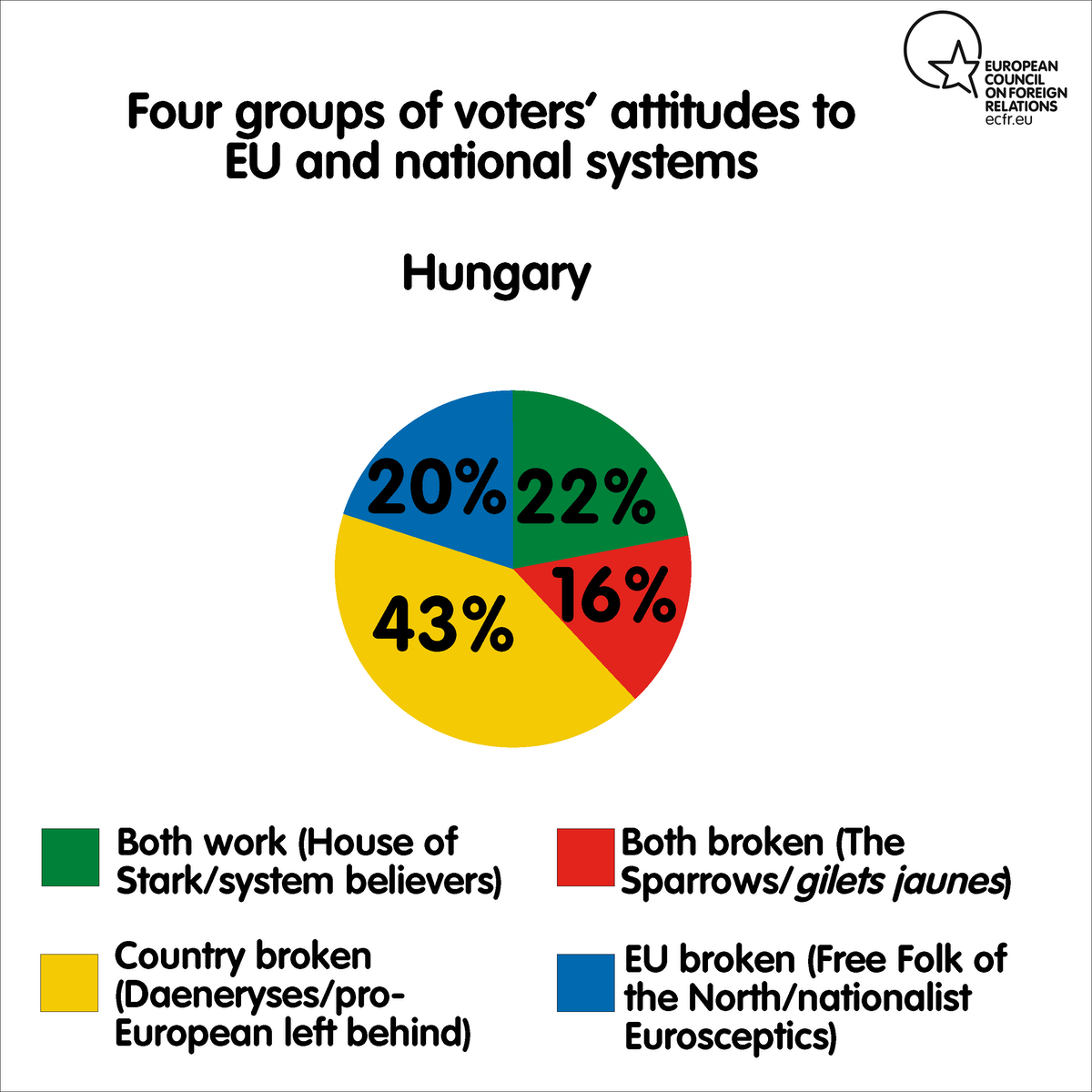

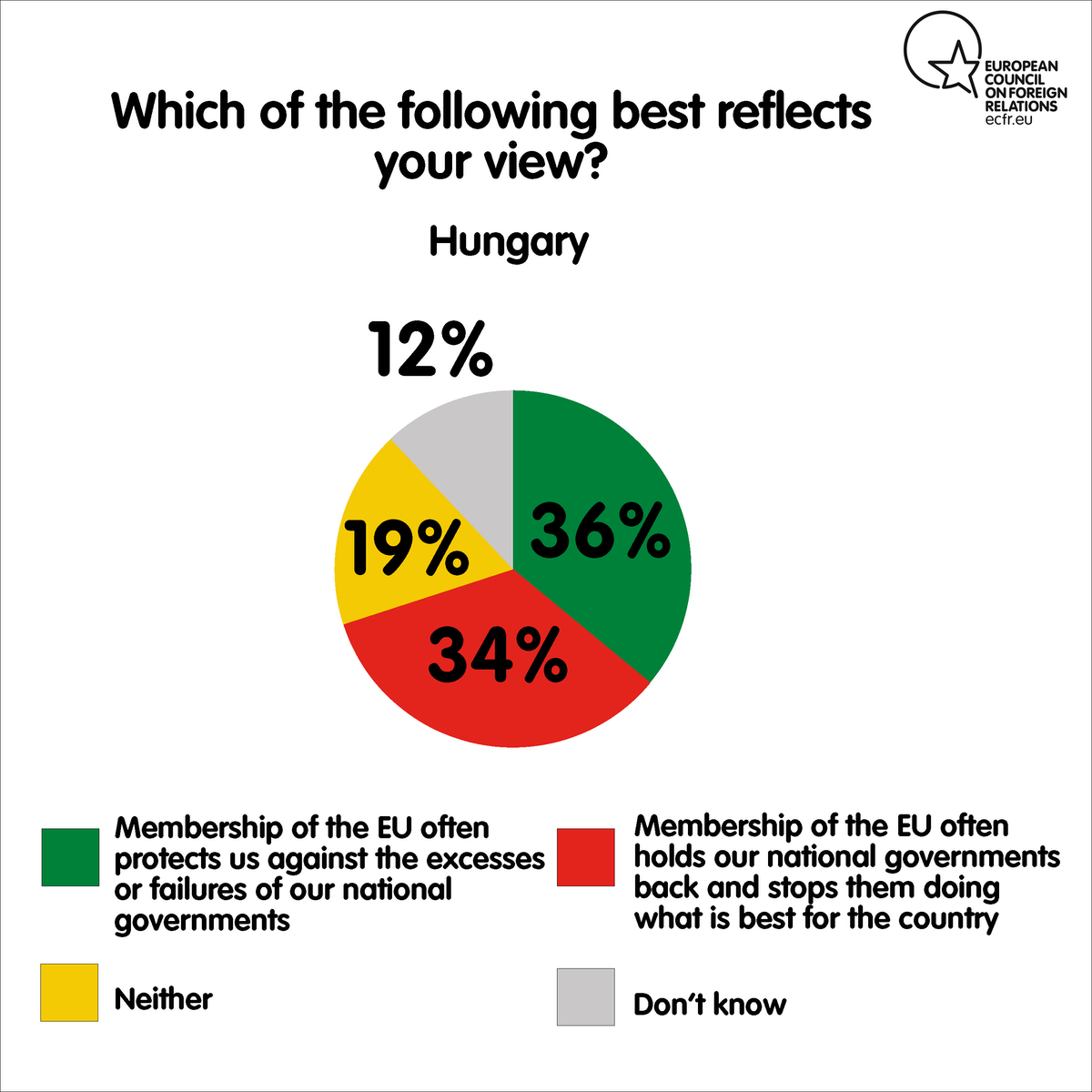

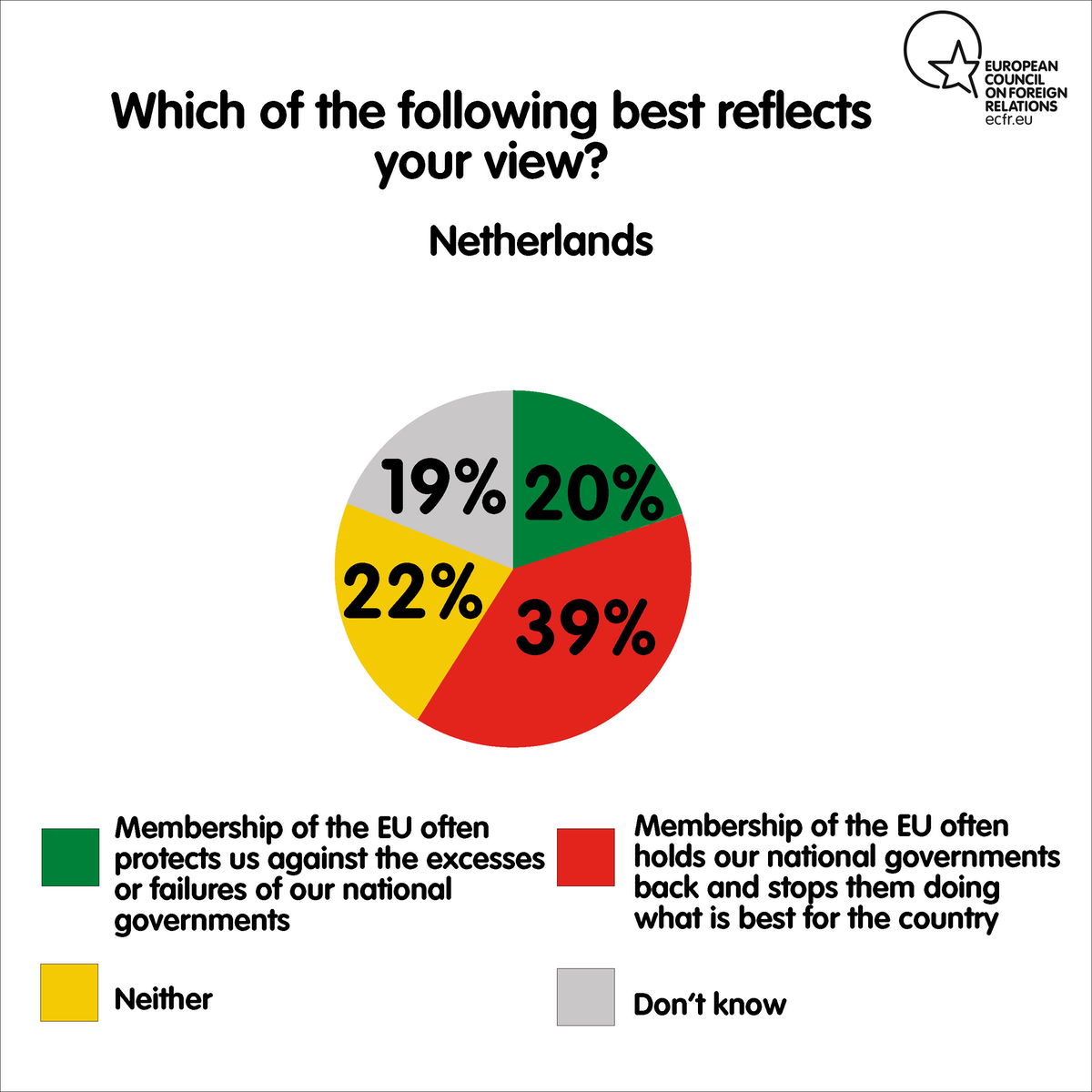

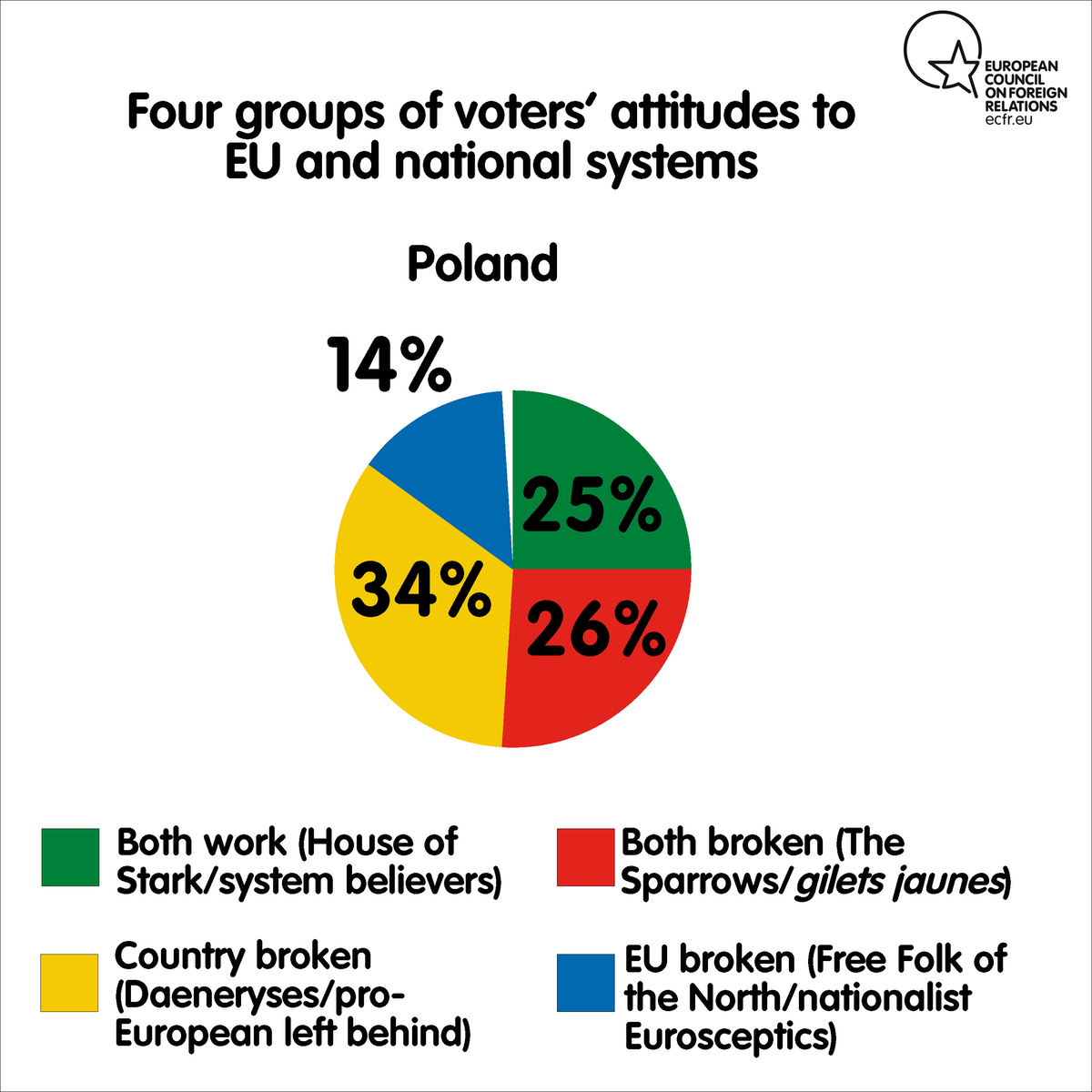

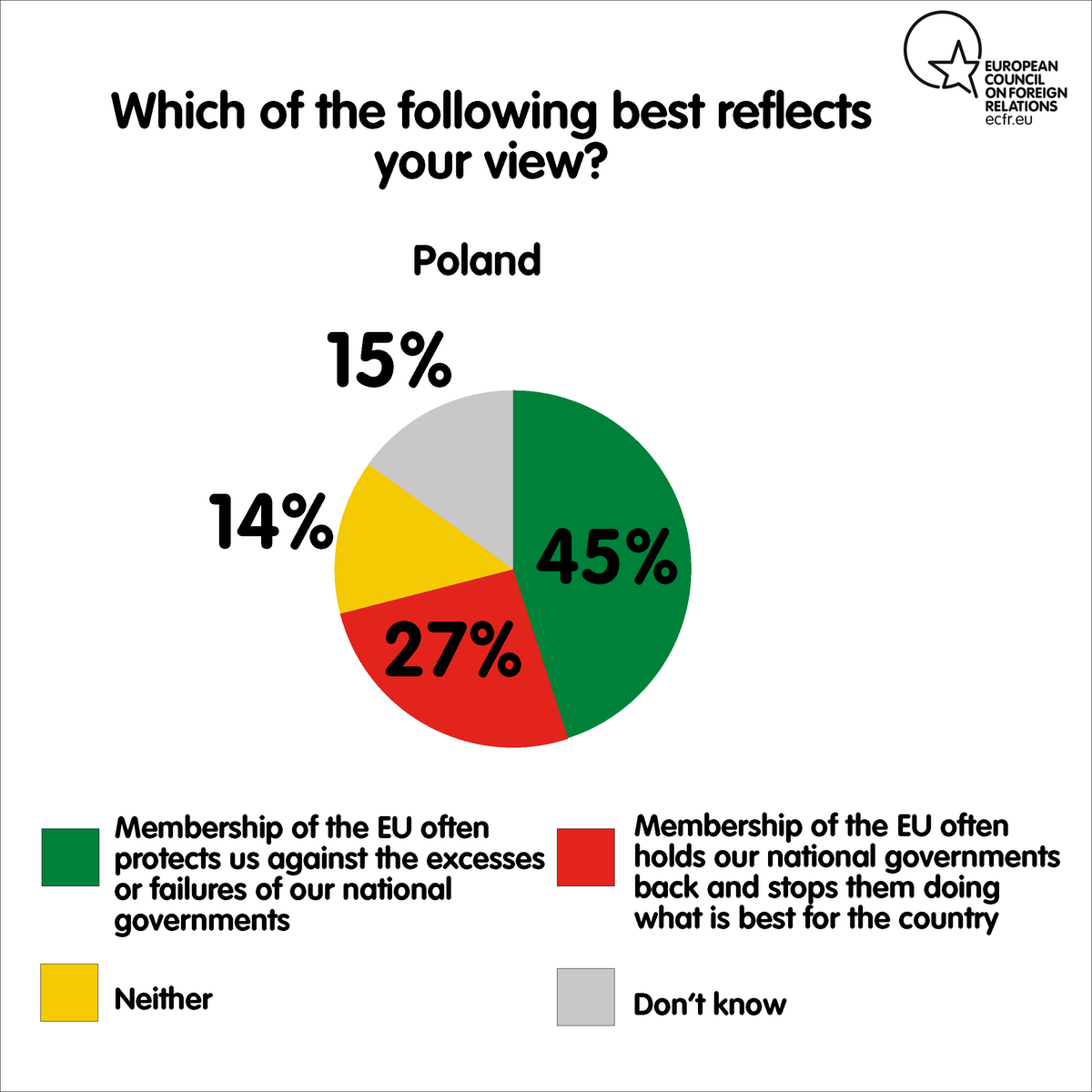

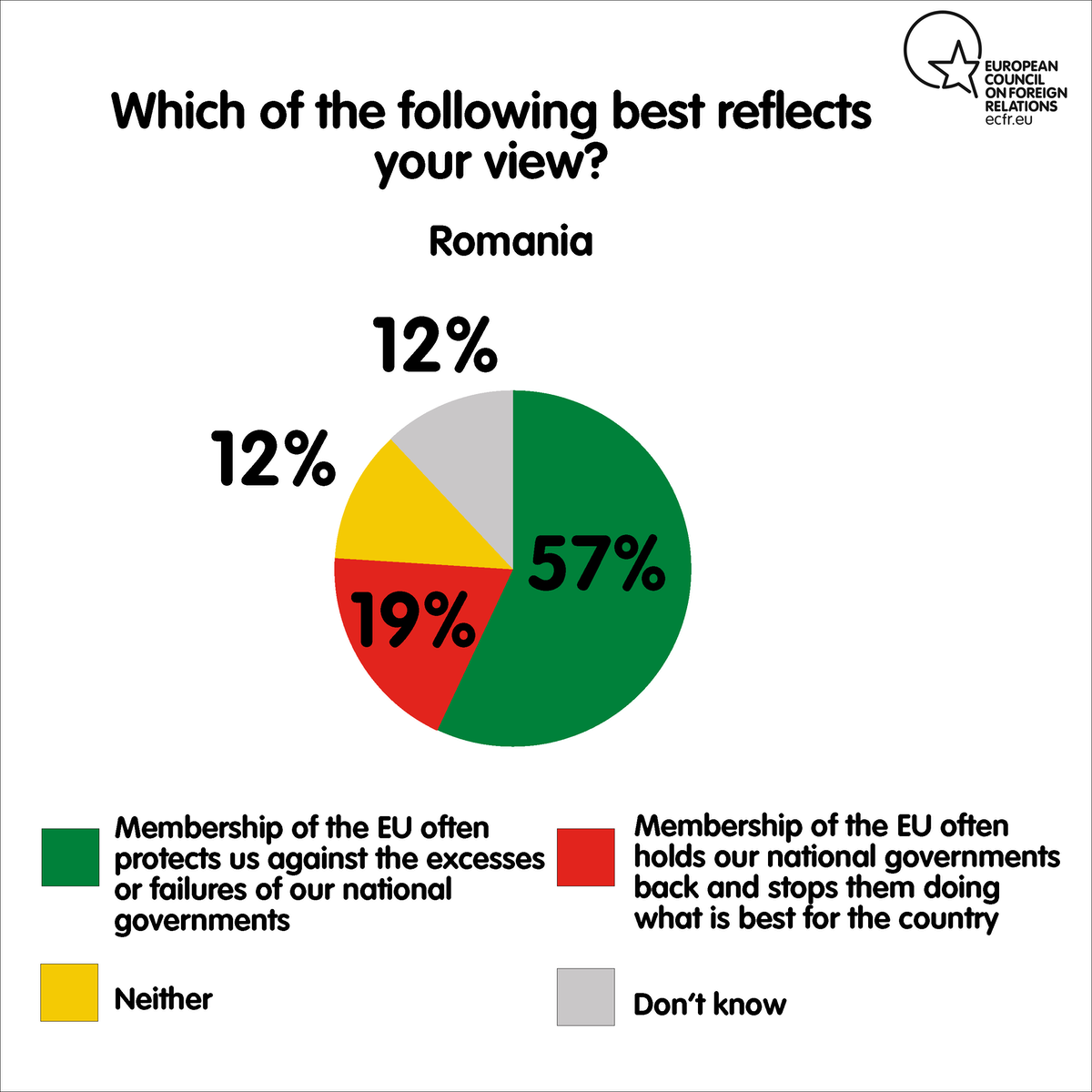

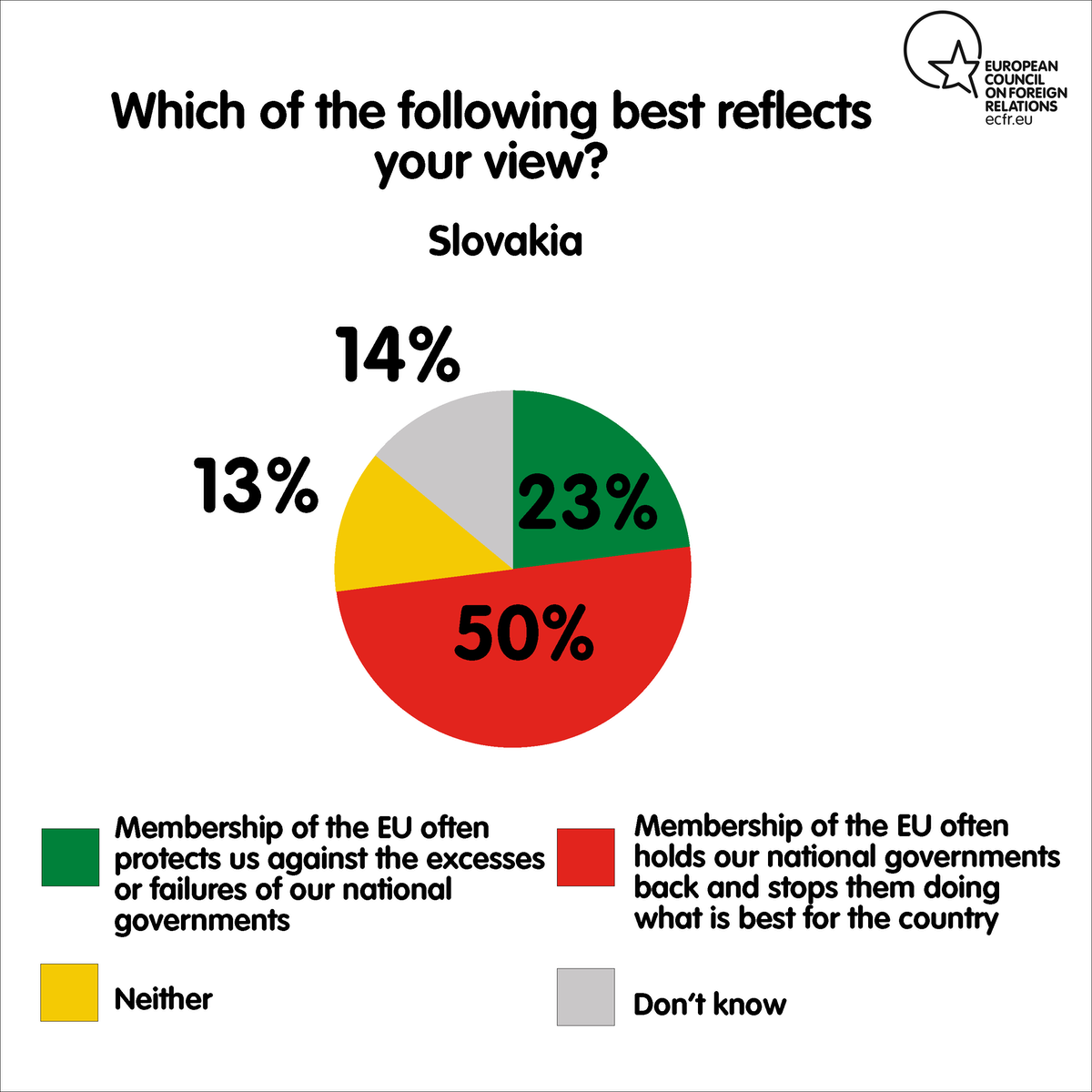

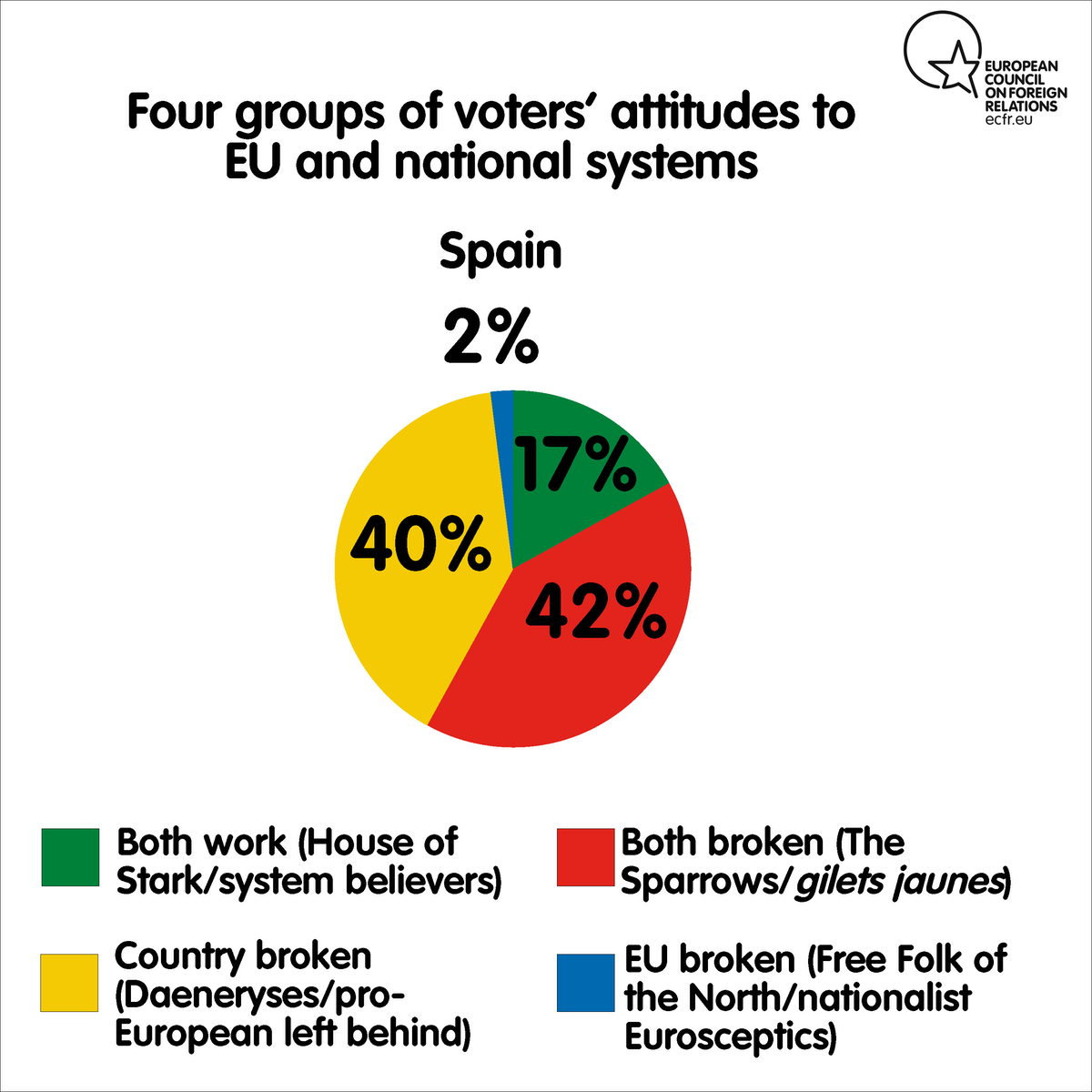

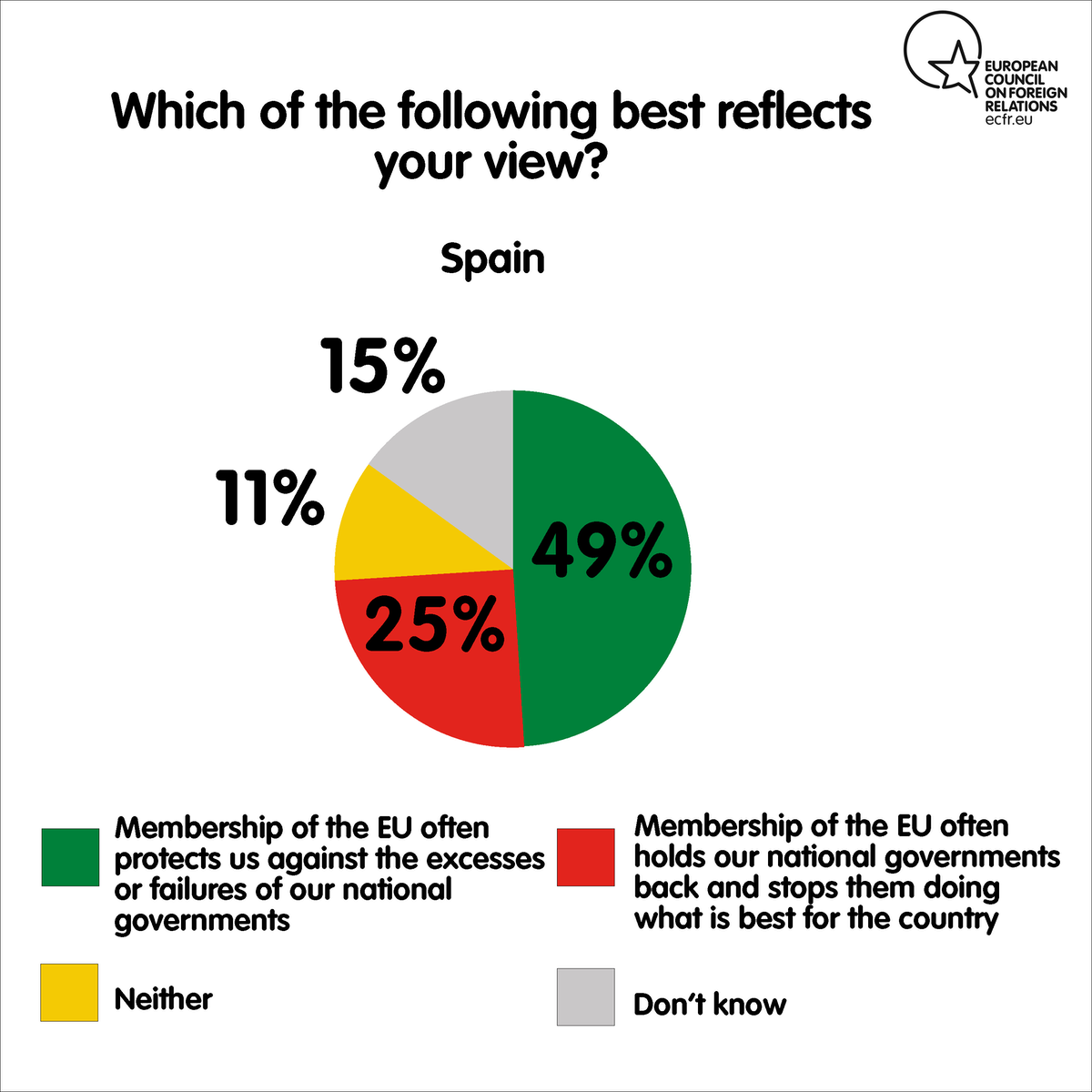

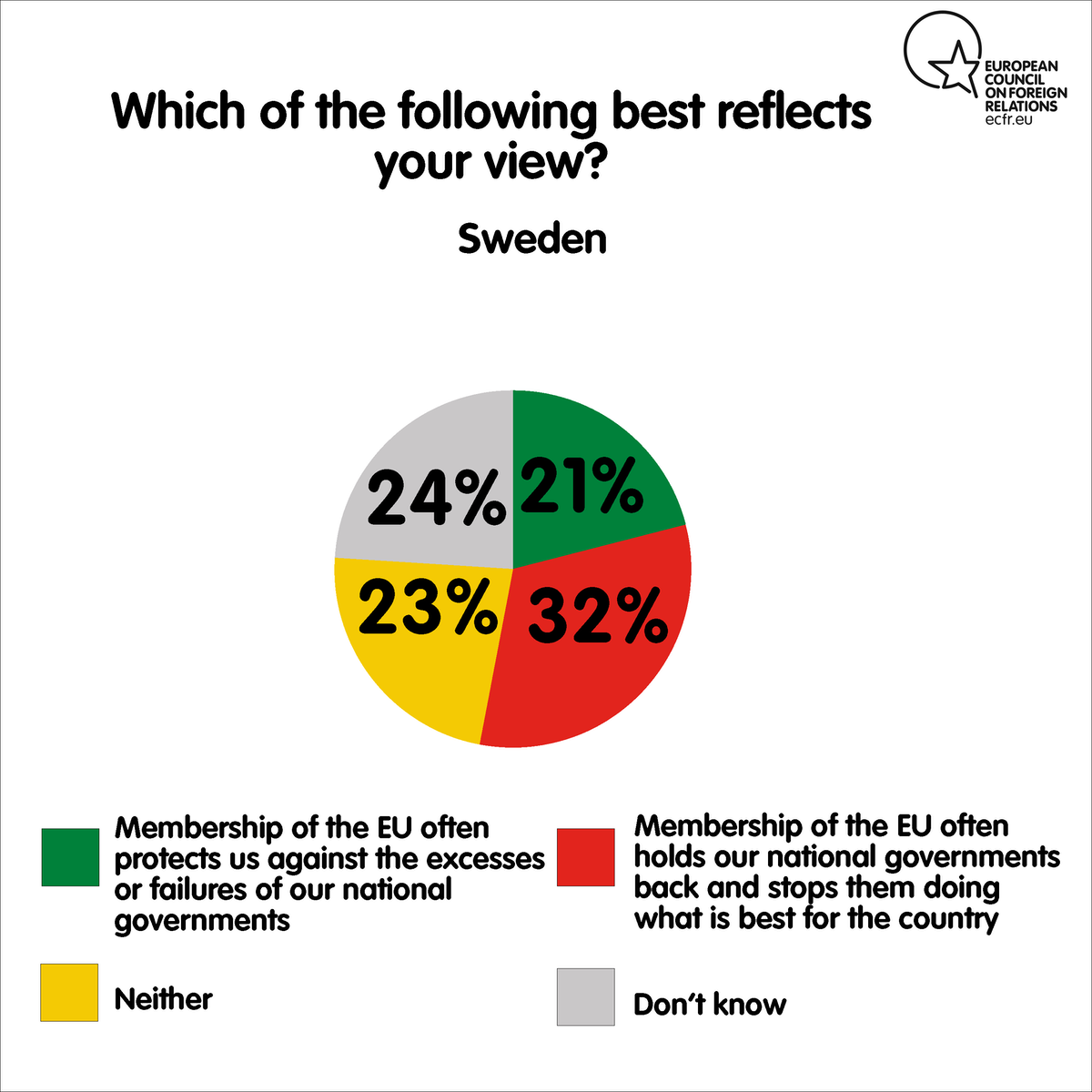

The poll shows that people have come to regard the EU as part of their system of government, with some seeing it as a constraint on that system’s ability to deliver and others as a check on excesses and failures. But this division does not fit with the stereotype of a pro-European west and an anti-European east. When asked about the perceived consequences of EU membership, Poland, Hungary, and Romania were (along with Spain) the countries with the strongest responses, saying that EU membership protects against the excesses and failures of national government. The bottom line is that the real division is not between pro- and anti-Europeans but rather comes from how people feel about their political systems.

At this time of uncertainty, a spectre is haunting European electoral politics: the yellow peril. In the late nineteenth century, the Russian sociologist Jacques Novikov coined the term “yellow peril” to conjure a fear of China. But for European leaders, the yellow peril is not about invaders from China – it is about protesters wearing yellow vests.

They have become the new face of political insurgency and anger. Though their direct impact on the upcoming elections is as yet unclear, they have captured the imagination of frustrated voters across Europe and have encouraged the fringes of the centre to vote more radically. Rather than comprising a stable, predictable electoral community of citizens who are organised into parties, the European political system has descended into an unpredictable battleground of constantly shifting alliances between groupings that come together momentarily before blowing up again afterwards. Some groupings are formed by people coming together from below and others are mobilised by strong leaders, operating according to different rules and cultures. In this brutal contest for influence, many are willing to use underhand tactics and conspiracy theories to gain the advantage. In this sense, European politics look less like the ideals of Athenian democracy and more like Game of Thrones.

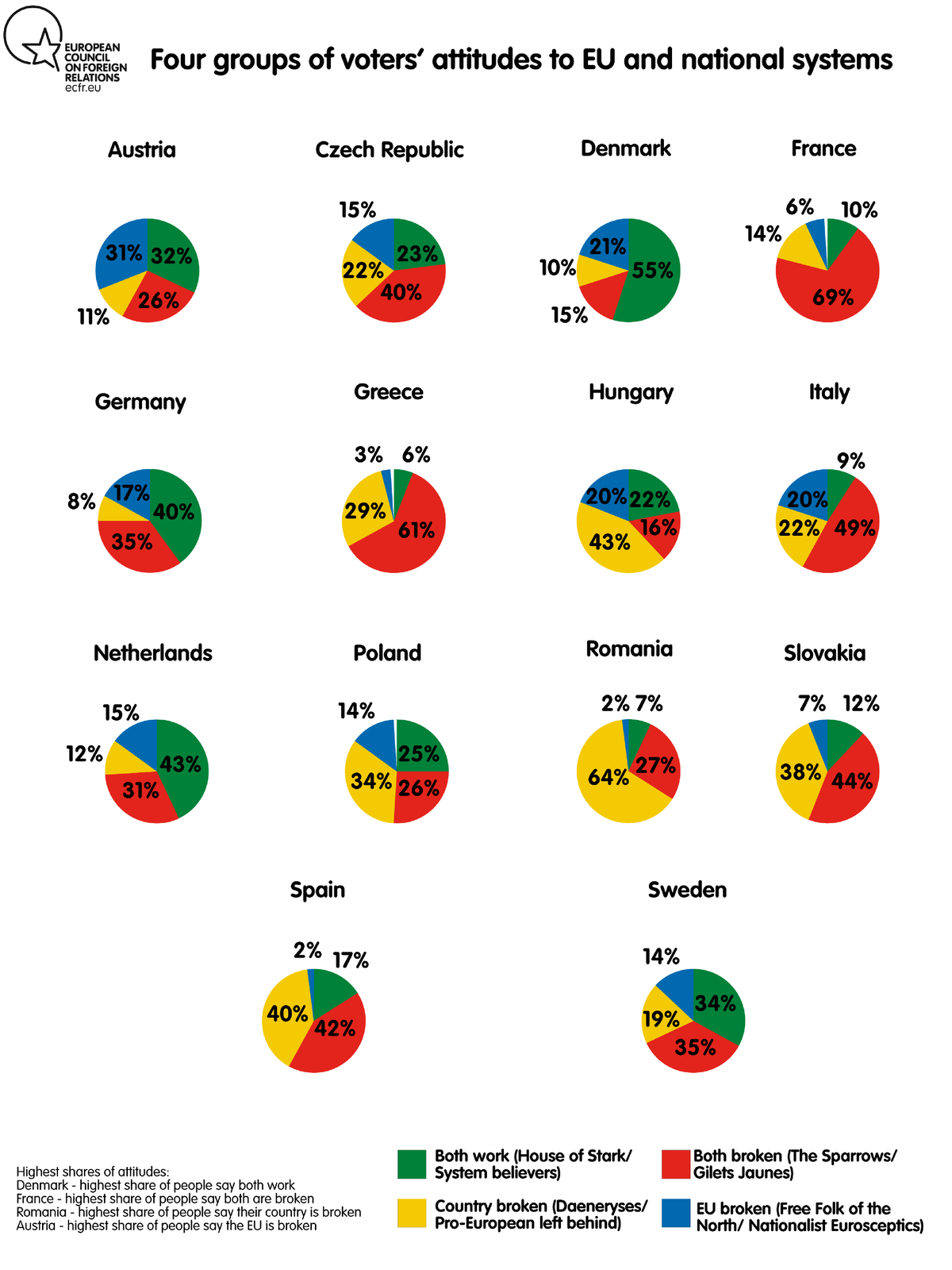

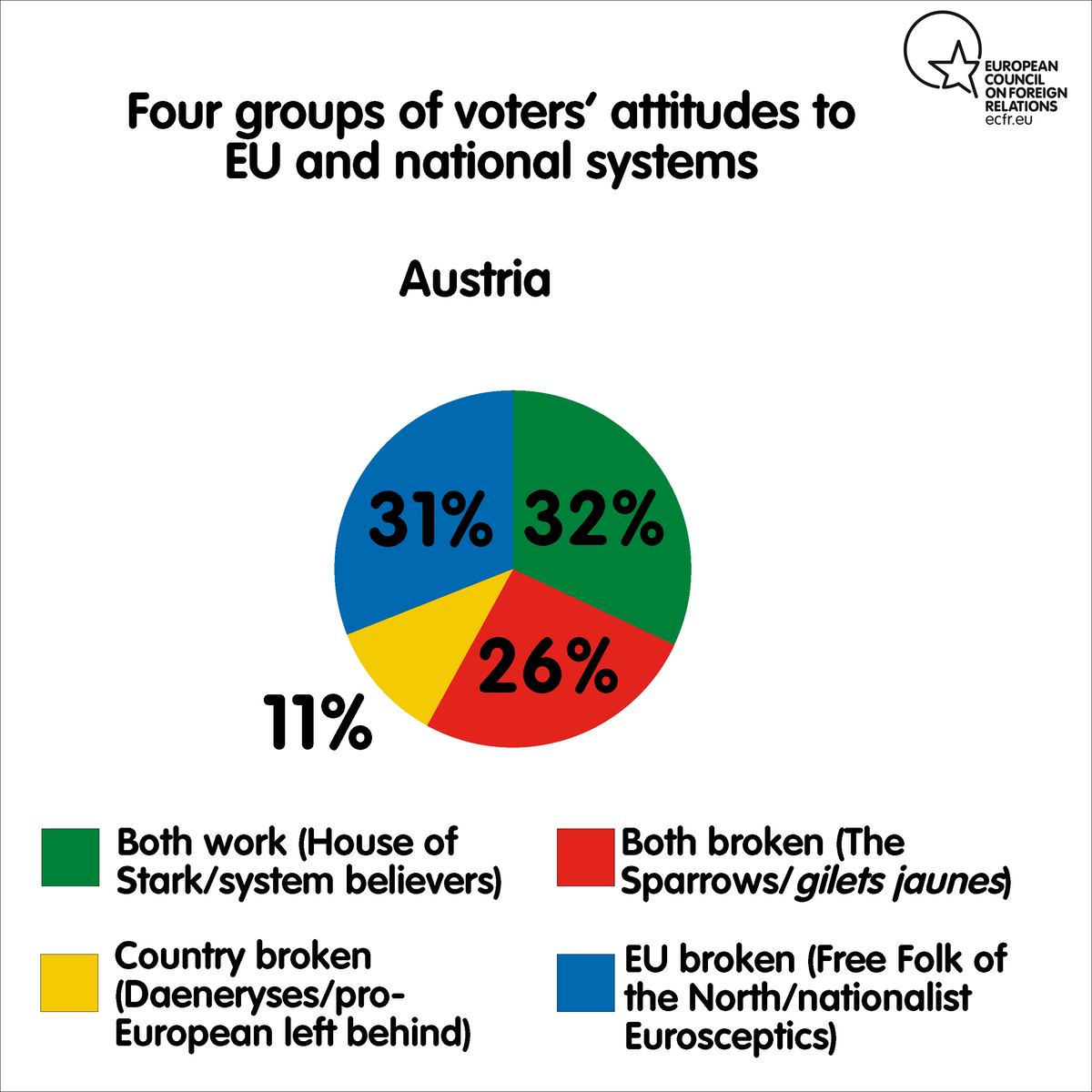

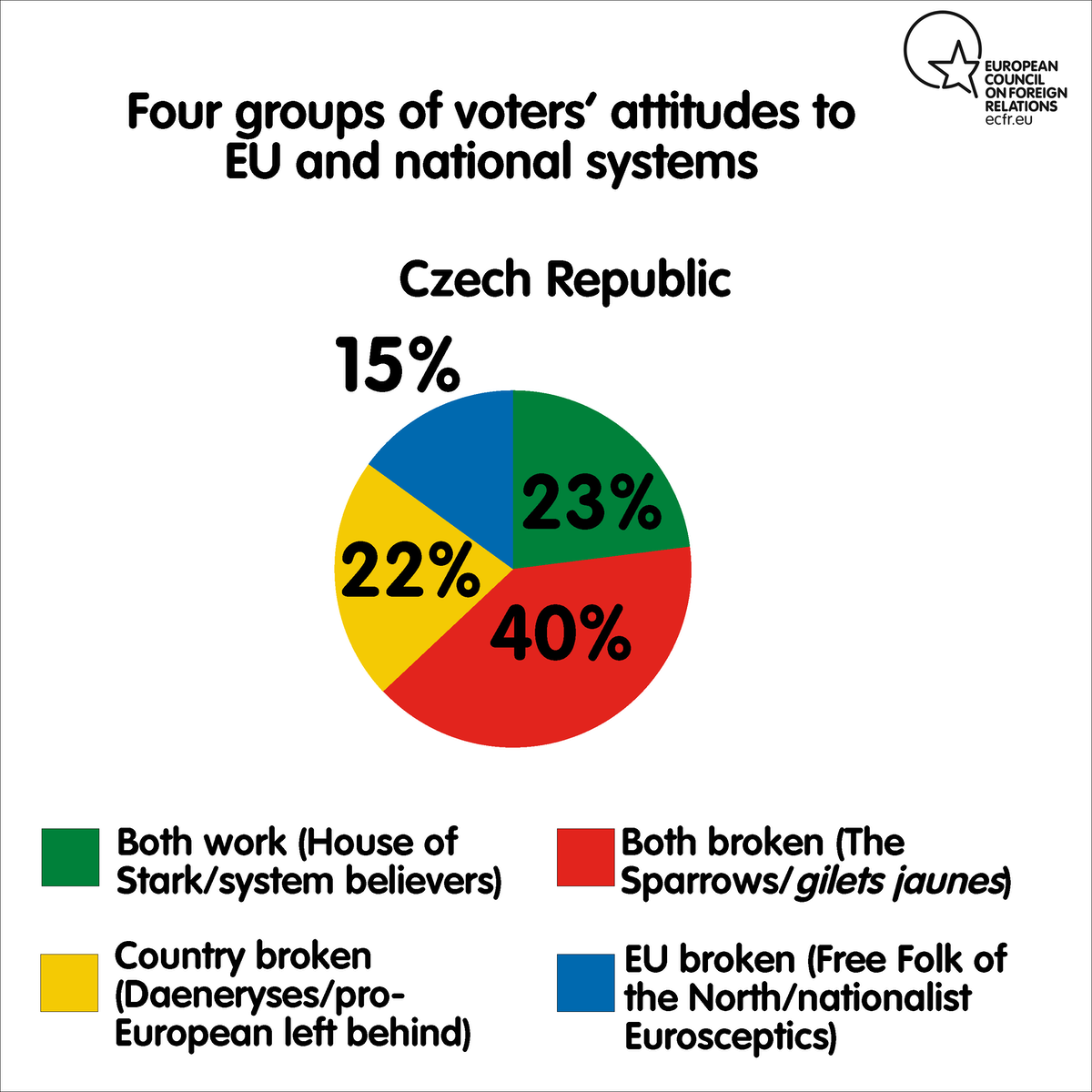

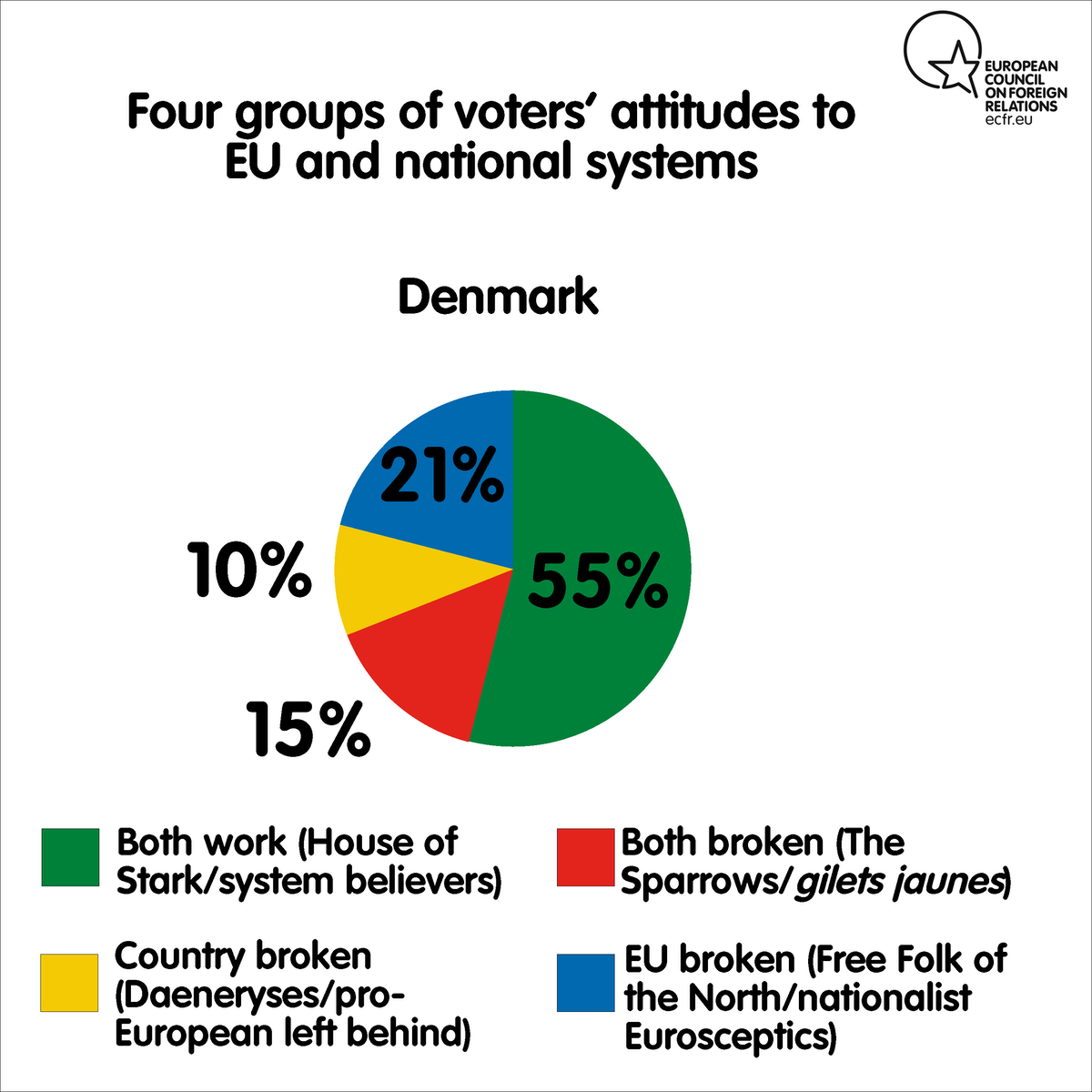

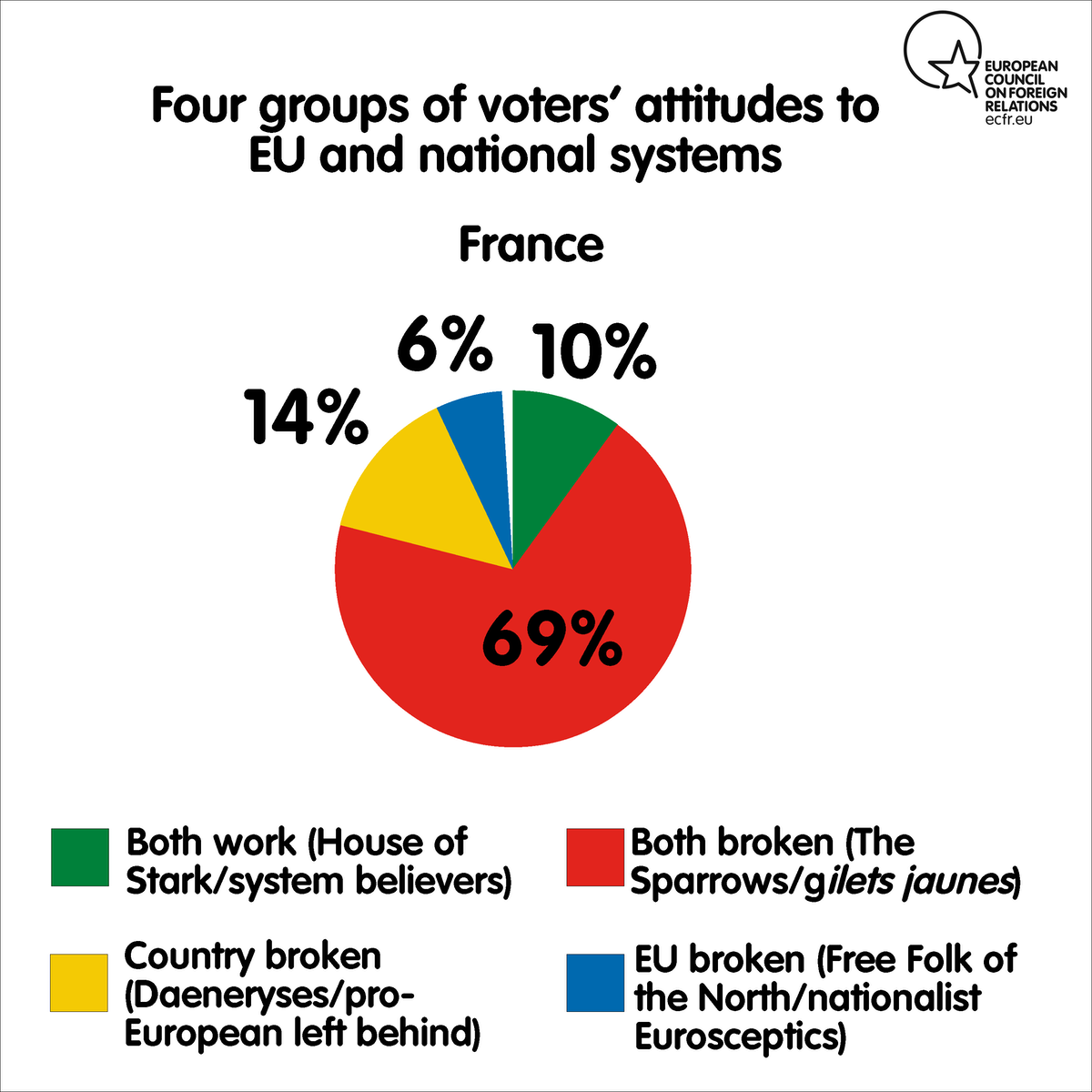

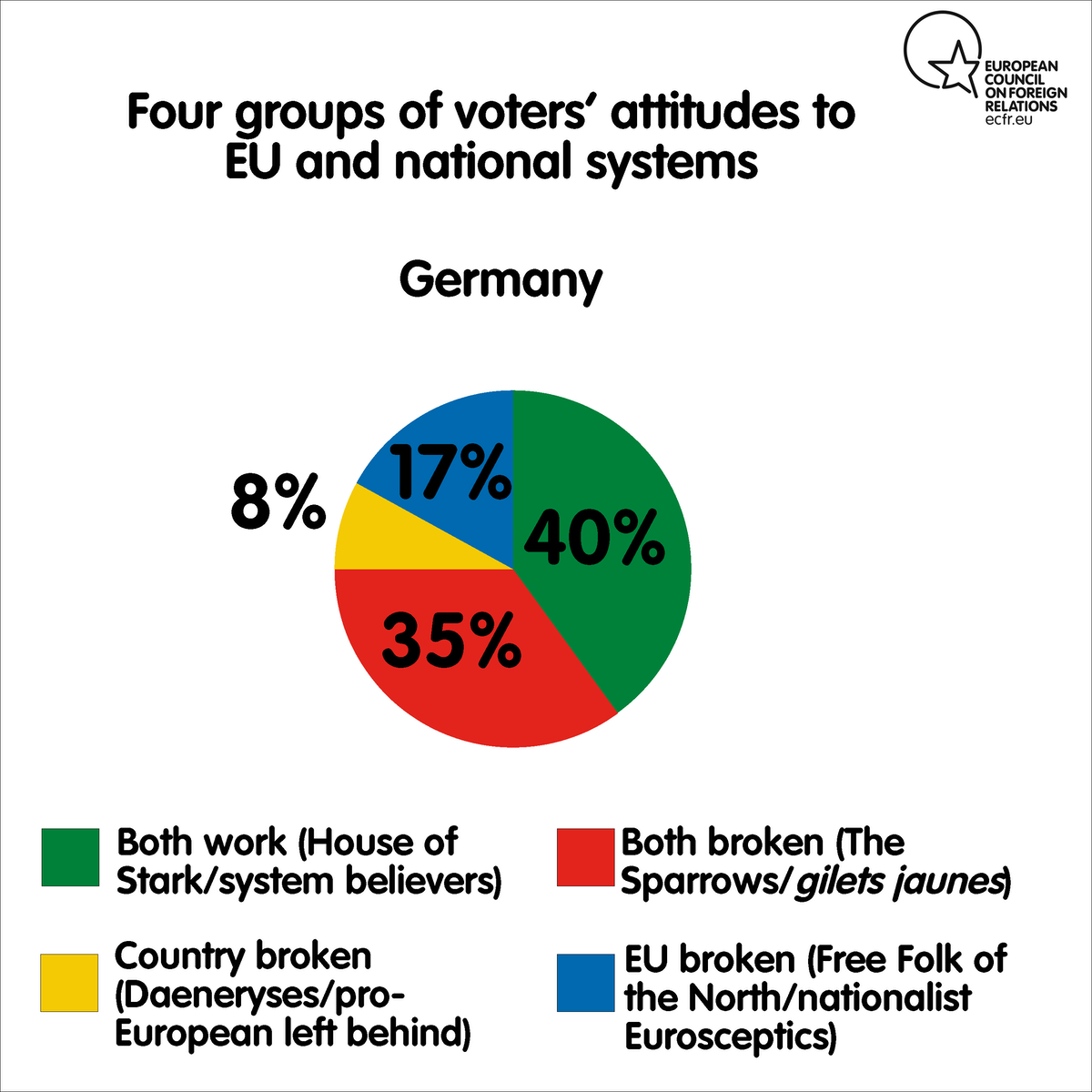

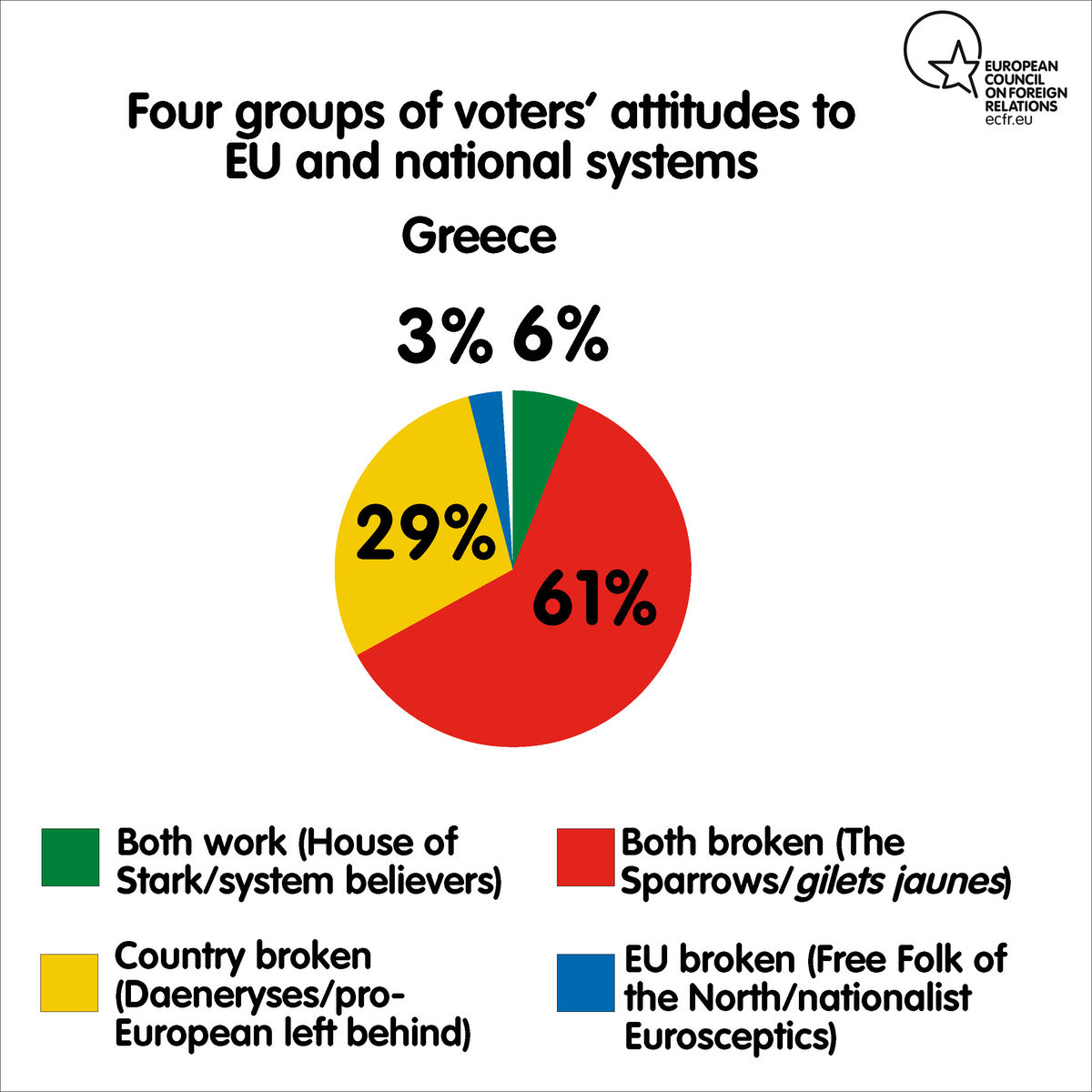

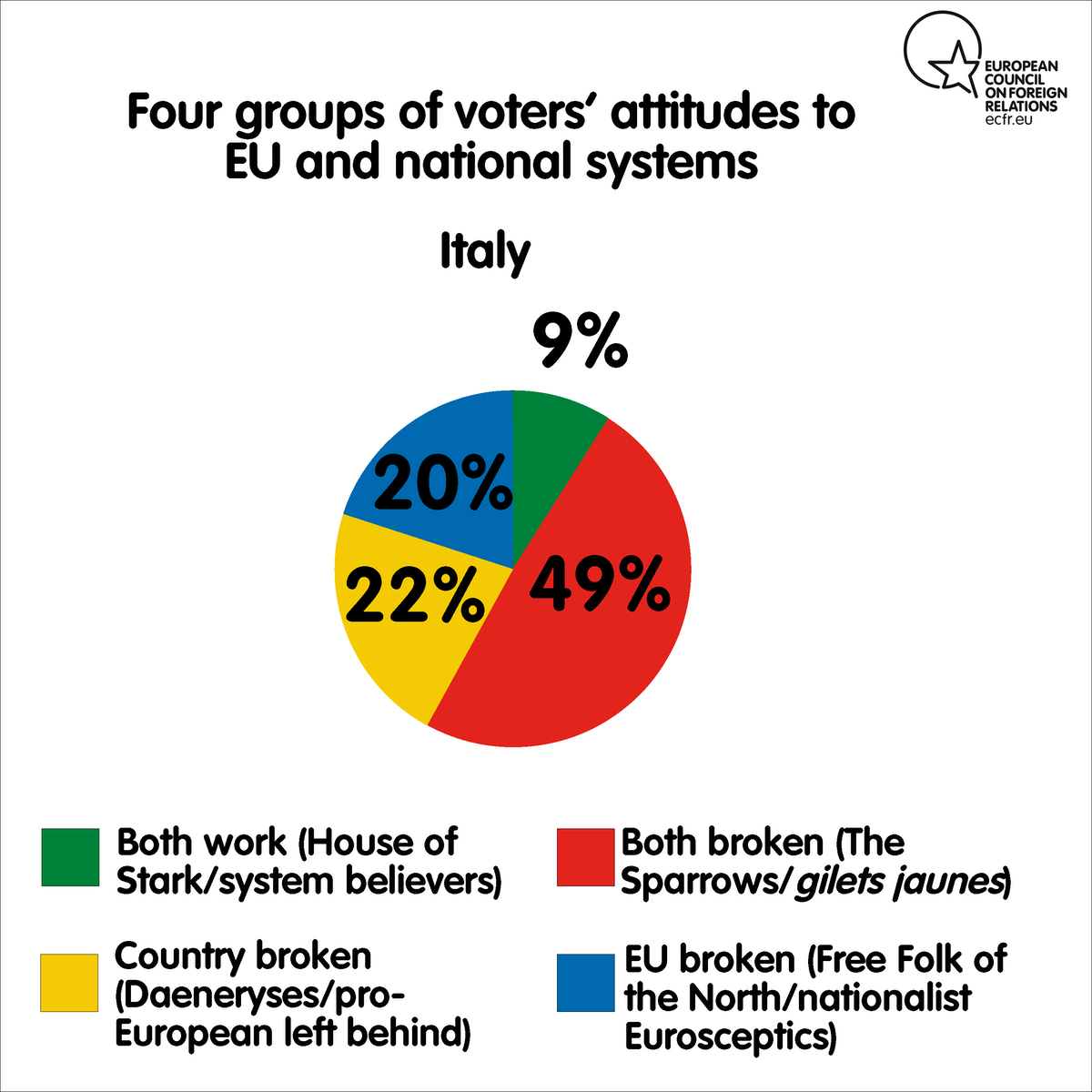

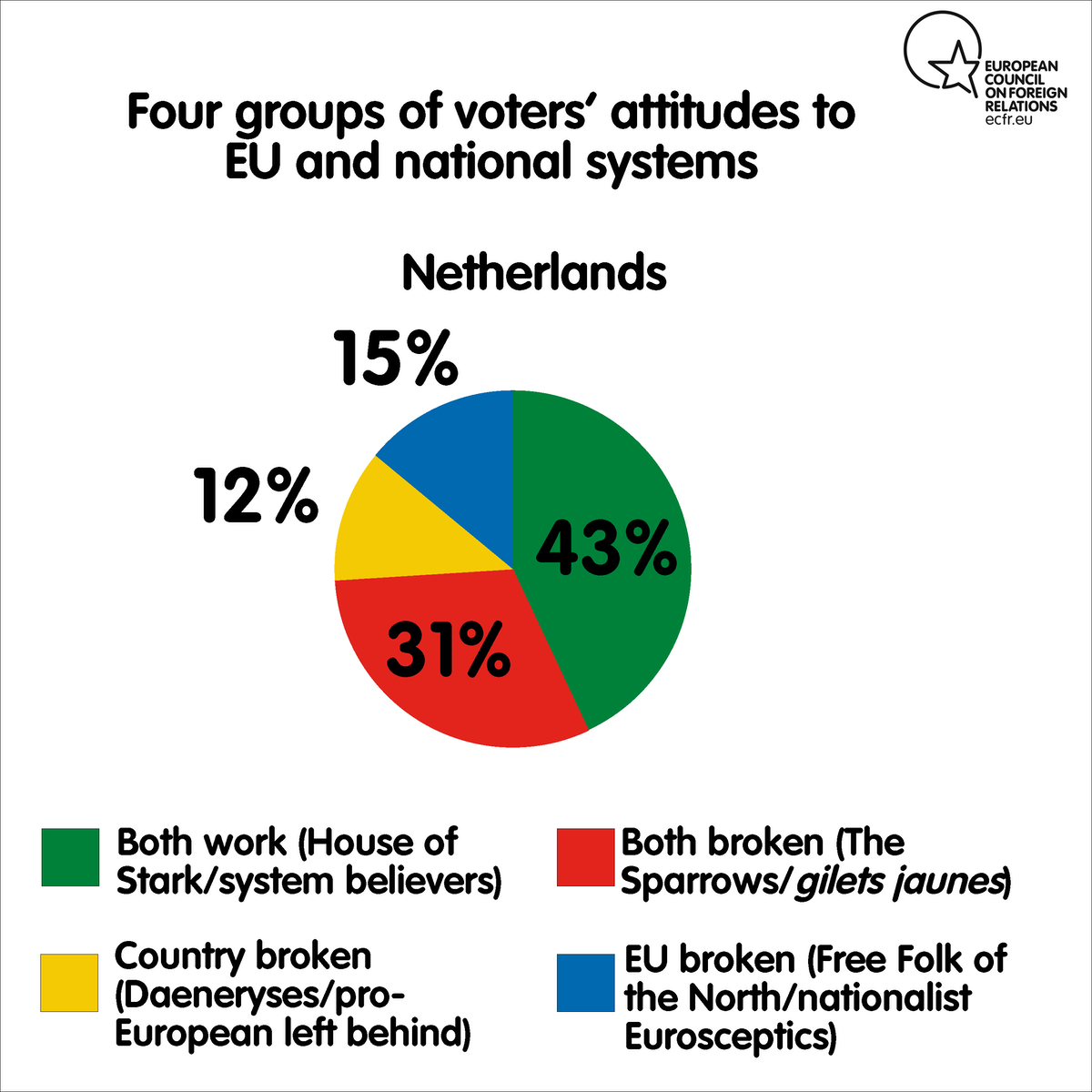

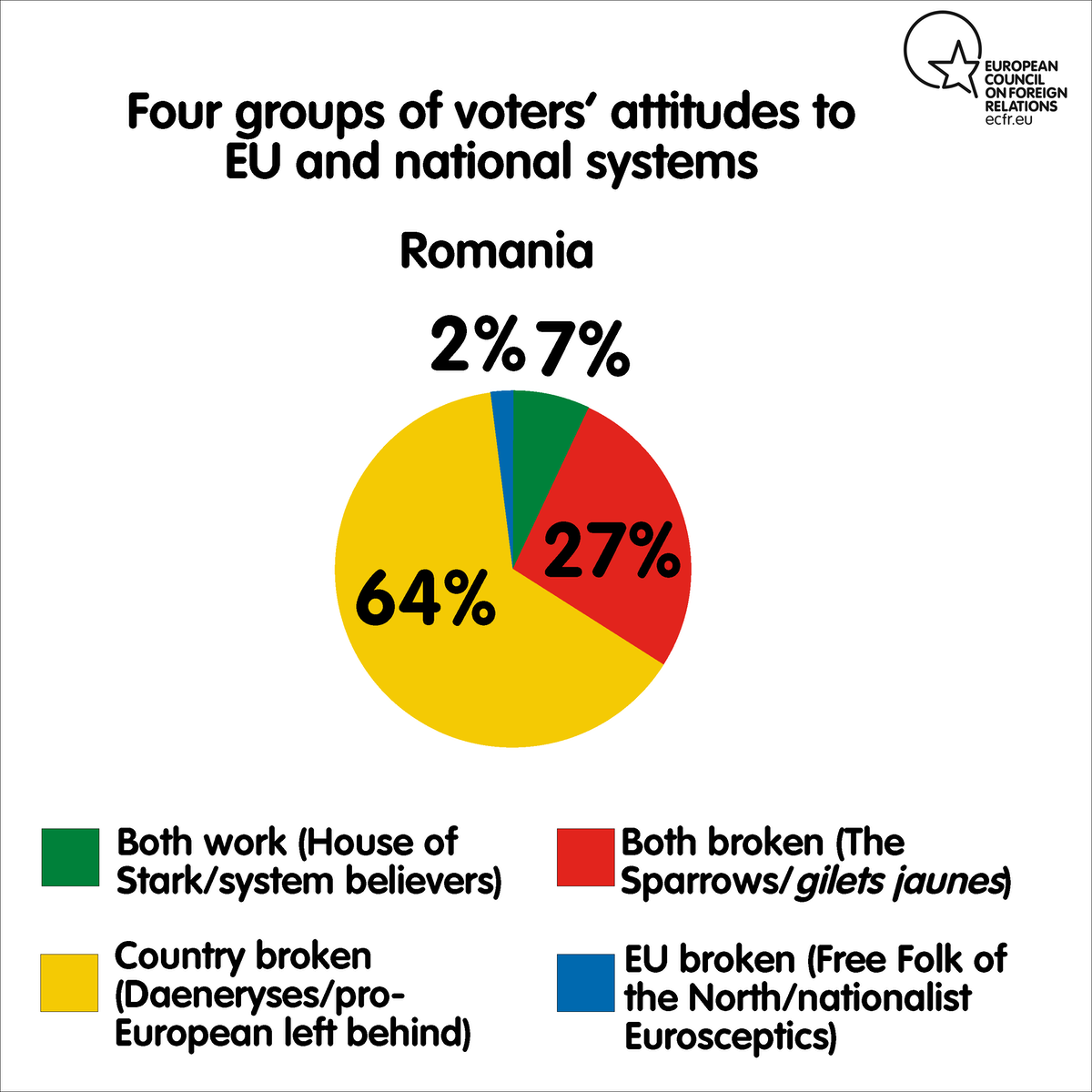

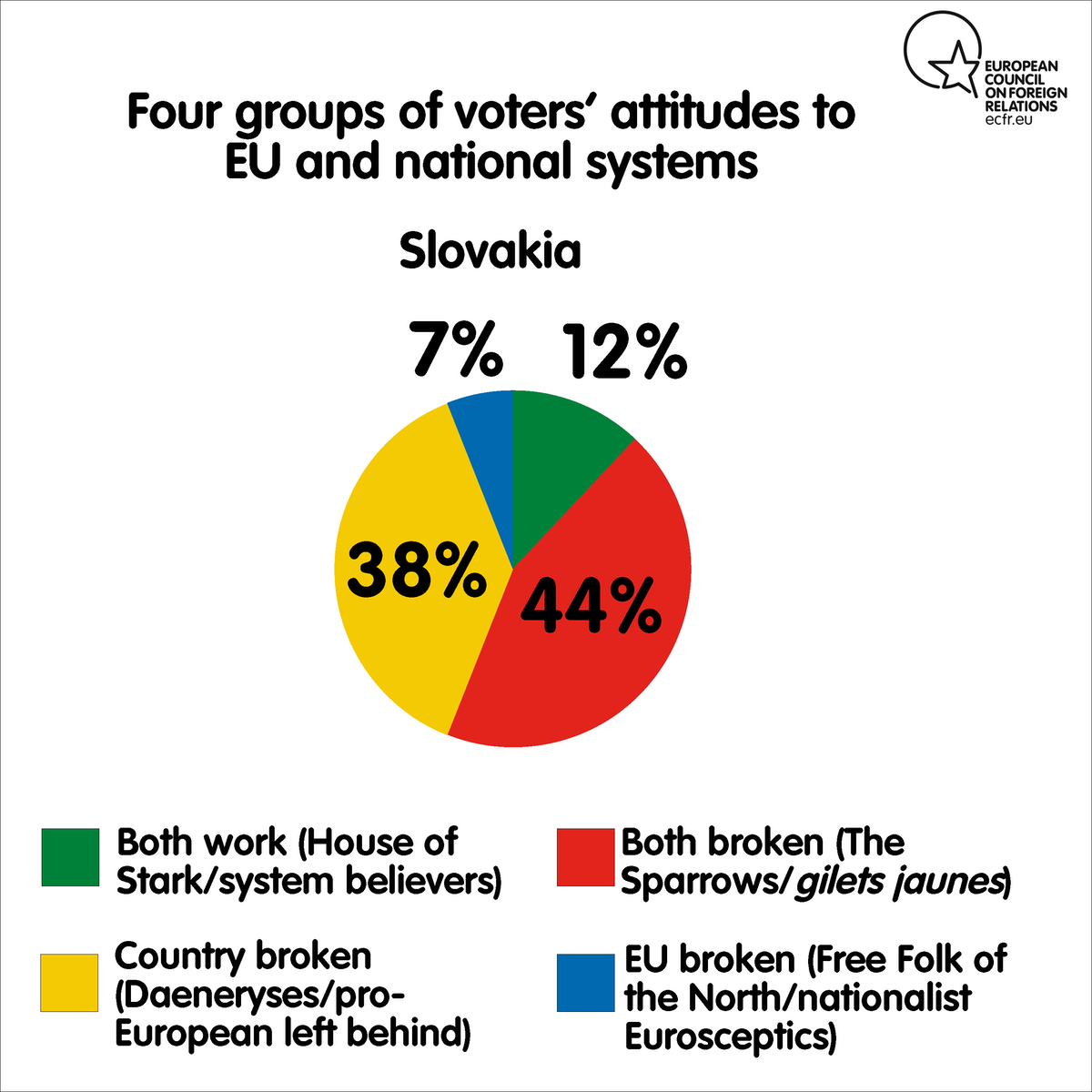

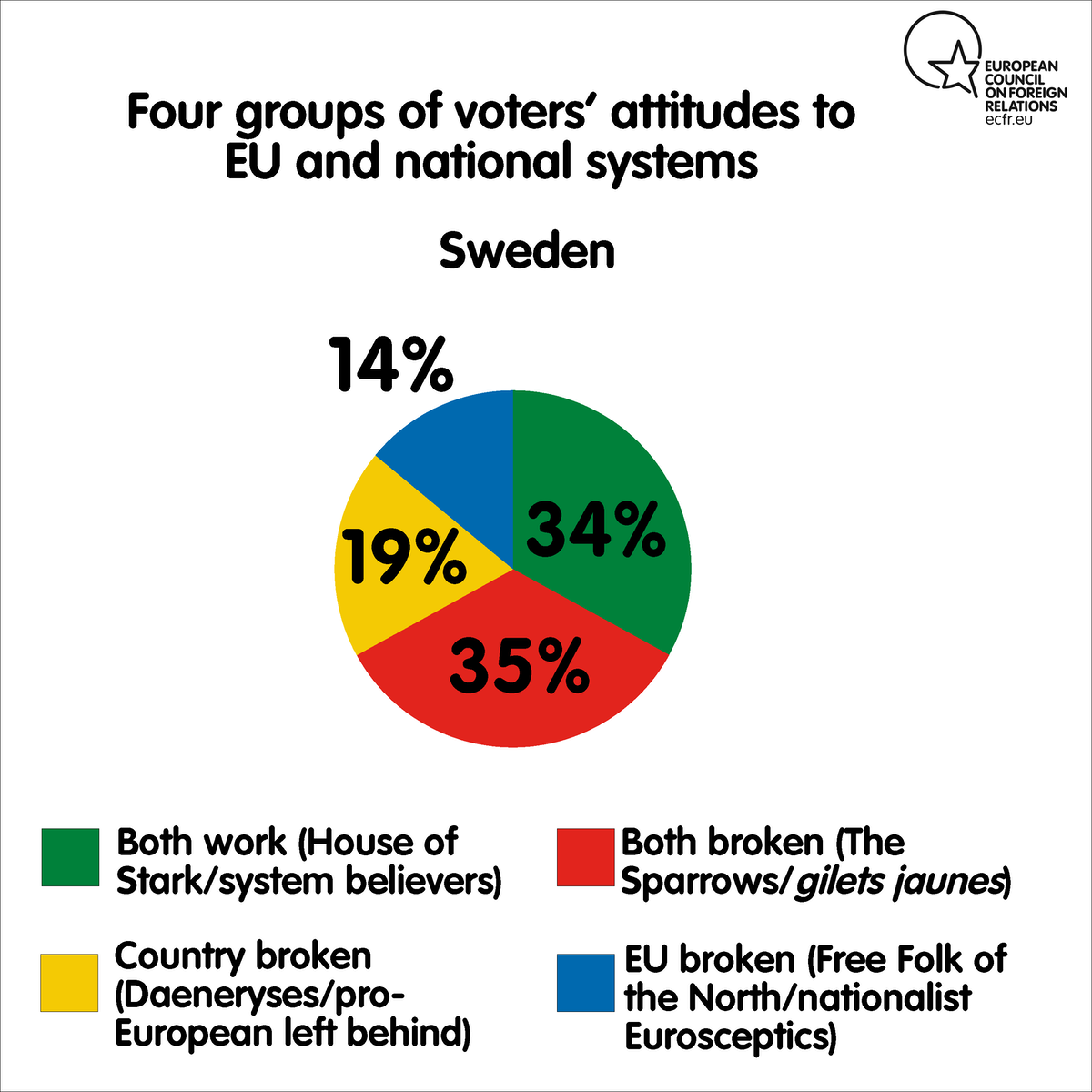

Through analysis of our survey of attitudes to whether the political system works well at the national and European levels, we have identified four big groups in the European electorate:

- “House of Stark” (the System Believers). This is the complacent class who believe that the system still works at both a national and a European level. For them, politics continue to operate by the usual rules. By voting, they can have their voice heard and influence their future. In Game of Thrones, the House of Stark continues to be bound by the traditional norms and customs – even as the House of Lannister and other families turn these rules on their heads

- “The Sparrows” (the Gilets Jaunes). These people have given up hope in both their national political systems and in the EU, because they think that all political systems are broken and cannot see how anything good can come of them. The only solution, therefore, is revolution – a popular uprising to cleanse society and start again. This is the vision of the High Sparrow in Game of Thrones, whose bottom-up political movement uses violence to humble the corrupt elites who have controlled political life for centuries.

- “The Daeneryses” (the Pro-European Left Behind). Like Daenerys Targaryen, mother of dragons, who frees slaves, these people wish to liberate Europeans from their shackles in restrictive nation states with a positive international vision; these people are looking for salvation in a transnational project. They think that their national systems are broken and look to a Brussels political system they still believe in to cure their country of its disease.

- “The Free Folk” (Nationalist Eurosceptics). These people think that the EU is a dangerous illusion that undermines national sovereignty. They want to return to self-governing member states. In this sense, they echo the fiercely independent Free Folk, who value self-reliance over idealistic attempts to unite humanity or the grandiose alliance-building of other political leaders.

The House of Stark (the System Believers)

Believing that both the European and national systems basically work, they constitute 24 percent of the EU electorate.

- Average age: nearing 50; but many younger members of the House of Stark are not planning to vote.

- Male/female: majority-male, but fairly representative of men and women.

- Where found: greatest representation in Germany, Denmark, and Sweden; can also be found in Austria, Hungary, and the Czech Republic.

- Other defining characteristics: comfortably off, usually with an upper-secondary education or more.

The Sparrows (the Gilets Jaunes)

Desperate revolutionaries who have lost faith in both the European and national political systems, they constitute 38 percent of the EU electorate.

- Average age: most mobilised Sparrows are older than 50.

- Male/female: slightly more women than men, and significantly more female in France and Italy.

- Where found: strongest in France, Greece, and Italy.

- Other defining characteristics: Sparrows are neither left-wing nor right-wing; the disengaged voters in this group have the same average income as those in the House of Stark.

The Daeneryses (the Pro-European Left Behind)

Convinced Europeans who feel that their national system is broken, constituting 24 percent of the EU electorate.

- Average age: disengaged Daeneryses are the youngest group of all, with an average age of 41.

- Male/female: this group is fairly evenly balanced, but with more female representation in Austria, Czech Republic, the Netherlands, and Sweden.

- Where found: highest concentrations in Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain.

- Other defining characteristics: The Daeneryses have the lowest average income of all the groups, and are largely made up of Millennials and Generation X.

The Free Folk (Nationalist Eurosceptics)

Nationalist Eurosceptics who feel that their country’s political system works but Europe’s does not, constituting 14 percent of the EU electorate.

- Average age: the oldest group overall, as is especially clear among the engaged voters in this group.

- Male/female: this group is fairly evenly balanced between men and women, but men predominate in some settings. In Denmark, men account for 64 percent of this group; in Austria, 62 percent. However, in Italy and Hungary, the group has strong female representation.

- Where found: high concentrations in Austria, Denmark, and Italy.

- Other defining characteristics: The Free Folk are better off than the Daeneryses. They are predominantly baby-boomers, and slightly to the right of them ideologically.

Cross-referencing the four groups with the parties their members say they are interested in supporting provides the best predictor of how voters how the voters assess some of the key challenges facing Europe today.

The core divide is not one of wanting either an open Europe or a closed nation state, but between voters who think that the system is broken and those who think the status quo still basically works. France and Denmark are polar opposites in this respect – 69 percent of people in France think both the national and the European systems are broken, while 55 percent in Denmark think both systems work well. This dynamic take has a highly local flavour, one which does not necessarily result in a shift against mainstream parties. In countries where anti-Europeans are in power, they are the status quo – but, in countries where they are in opposition, they have significant influence. However, the key lesson from the study is that success in this election depends on the ability to position oneself as a credible agent of change. It is about offering good positions on issues people care about. But equally important is whether voters trust politicians to bring about this change.

Myth 3: This will be a referendum on migration

The truth: Voters have a wider mix of issues on their minds

Bannon, Orban, and League leader Matteo Salvini have tried to turn the election into a referendum on migration, mobilising a sovereigntist coalition to dismantle the EU from inside. They think that the 2015 migration crisis upended European politics, and that this was the beginning of a permanent change, putting mainstream parties on the defensive and going to the heart of European insecurity about identity. They are hoping for an increase in migration pressure in the coming weeks that will shift the balance of the discussion in their favour.

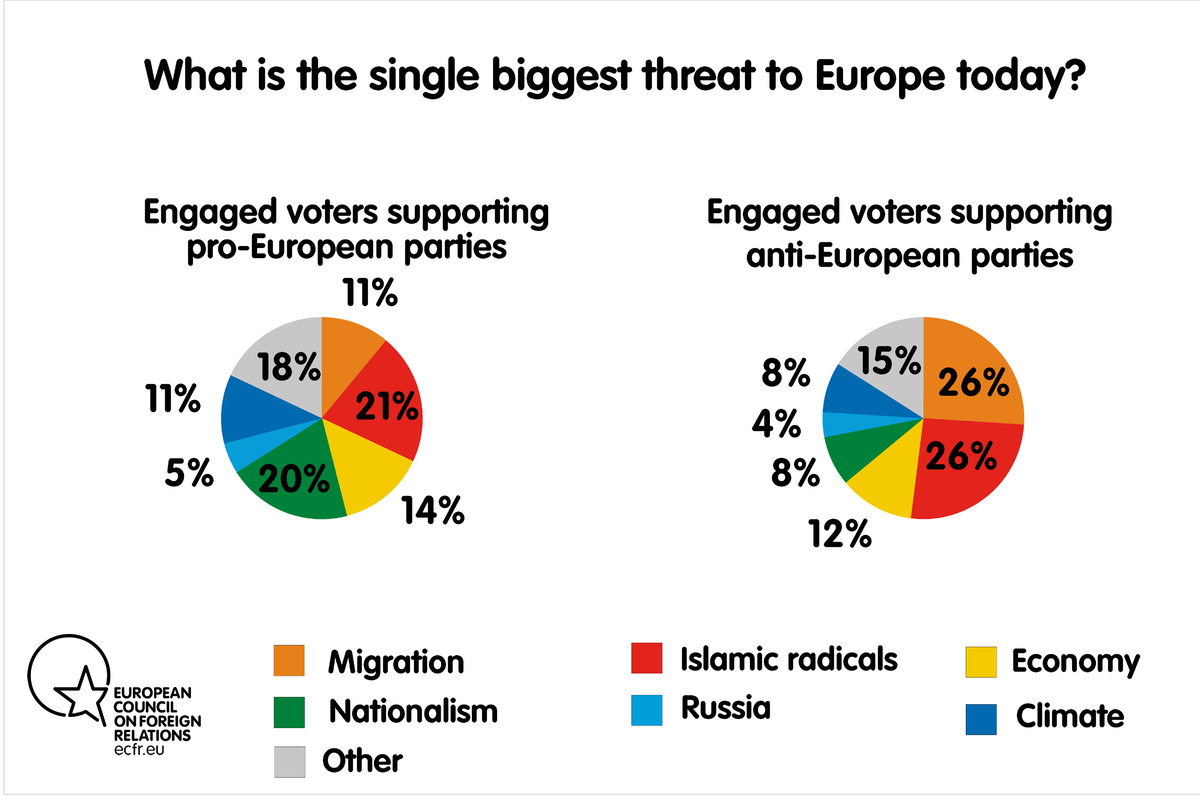

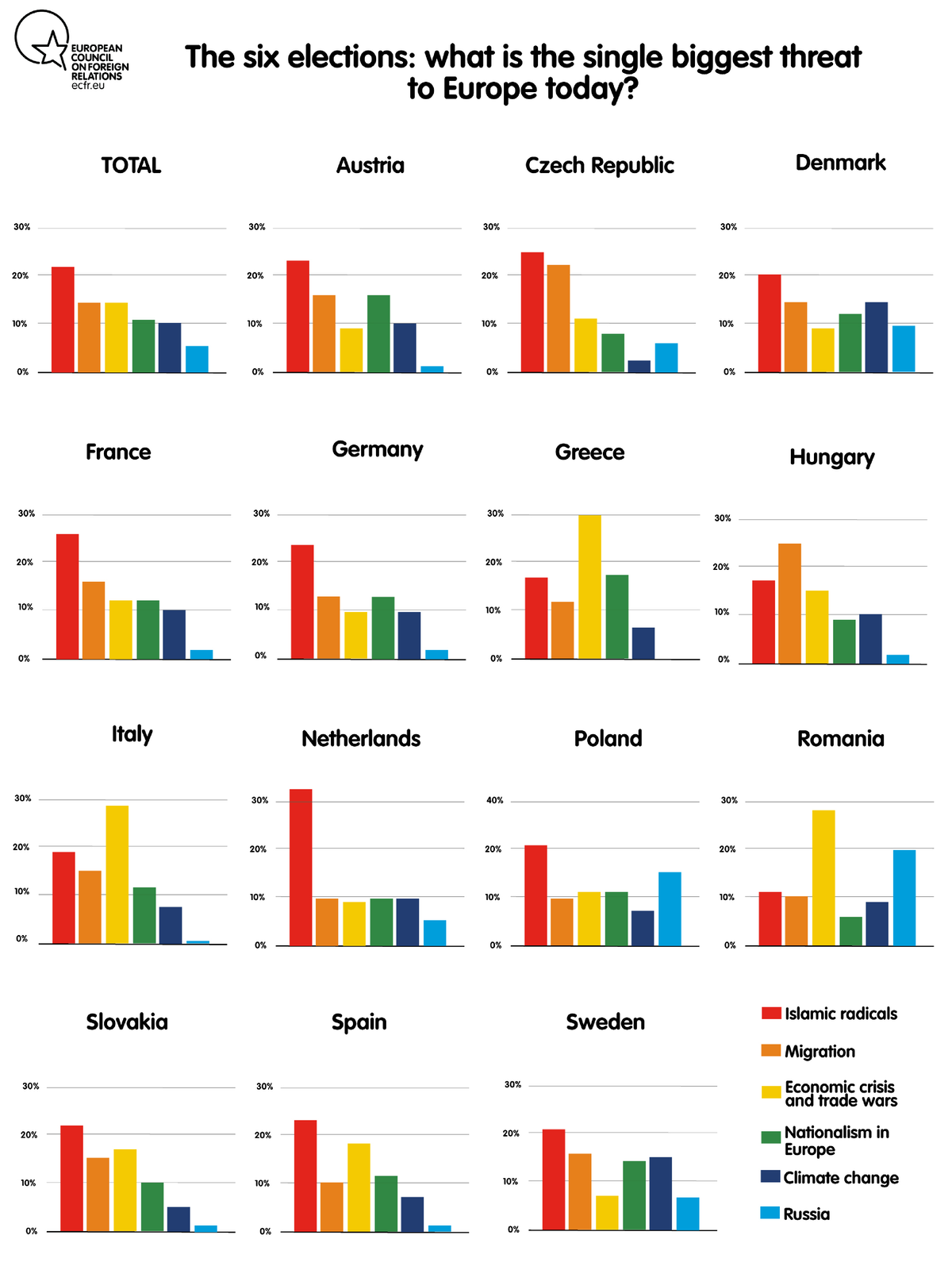

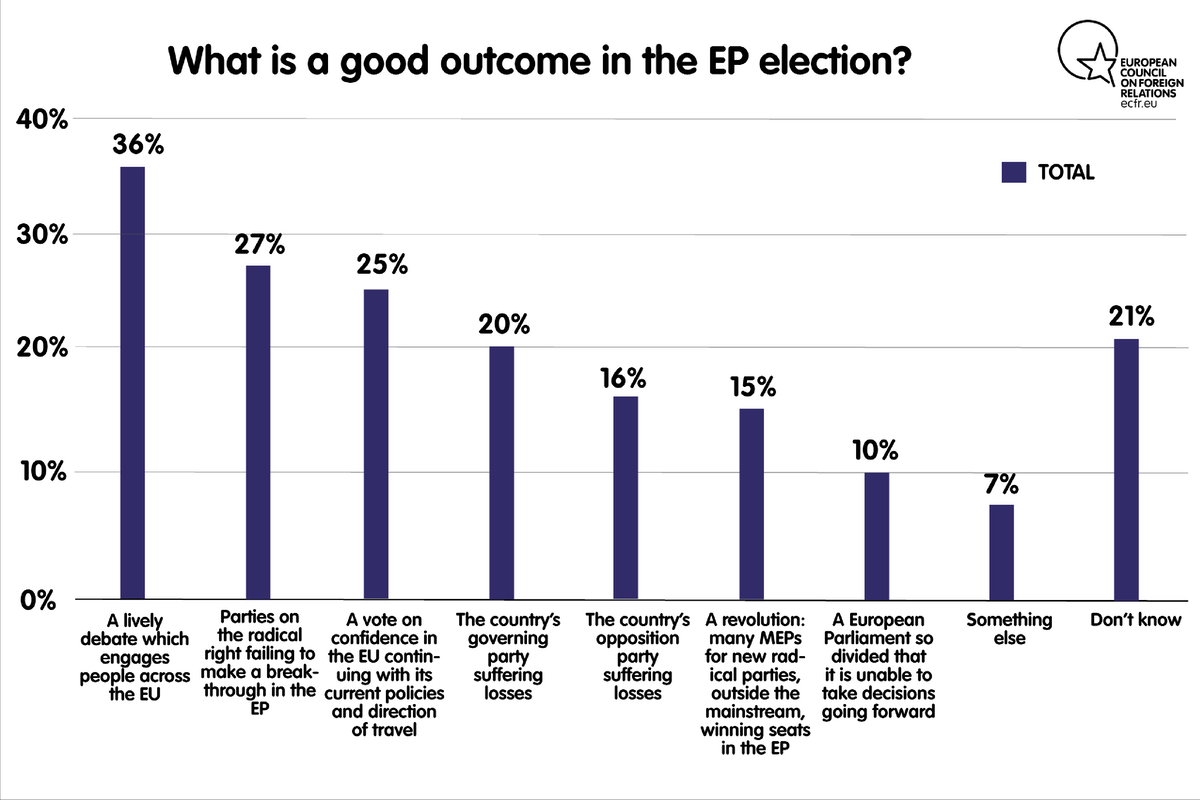

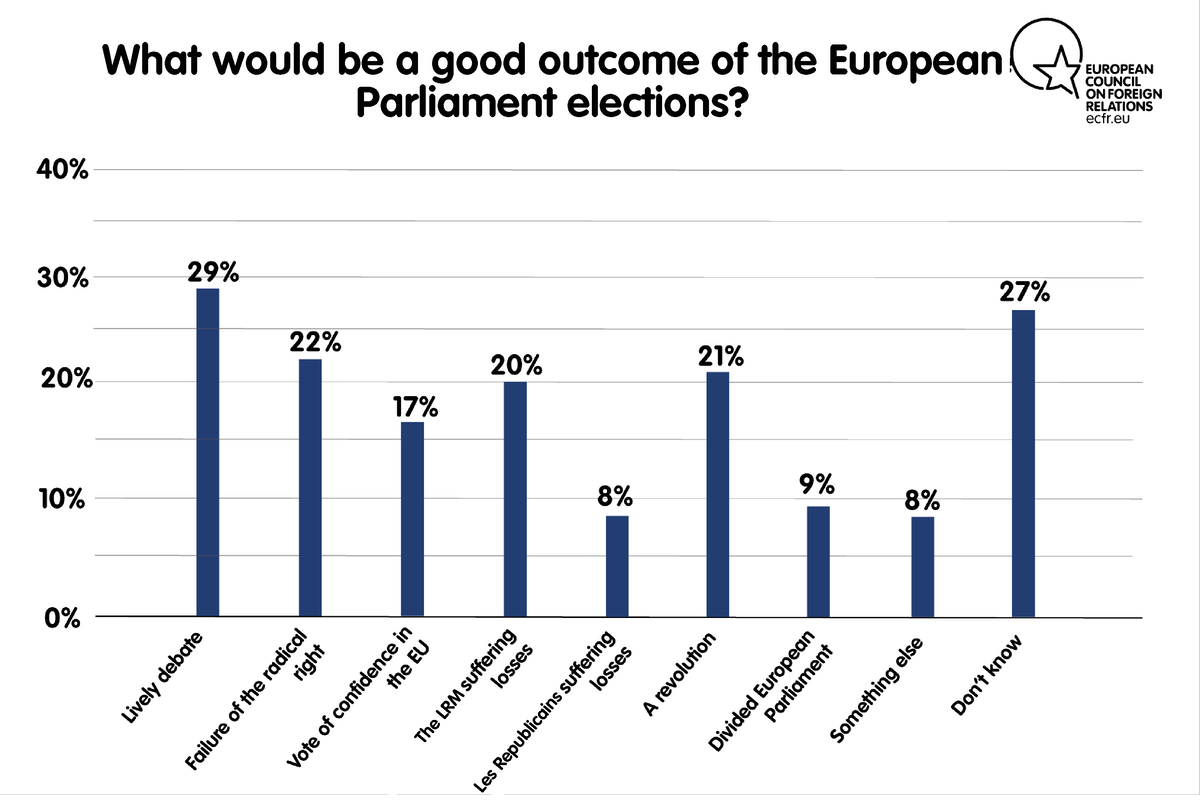

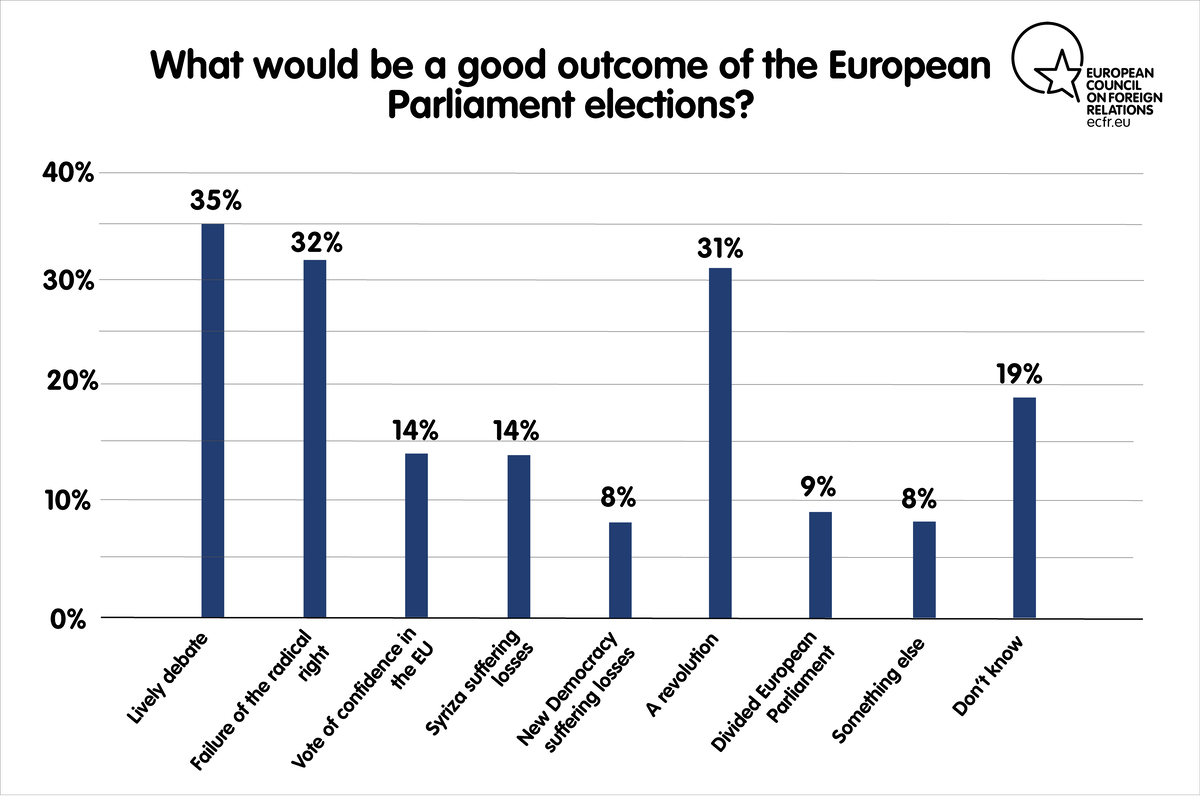

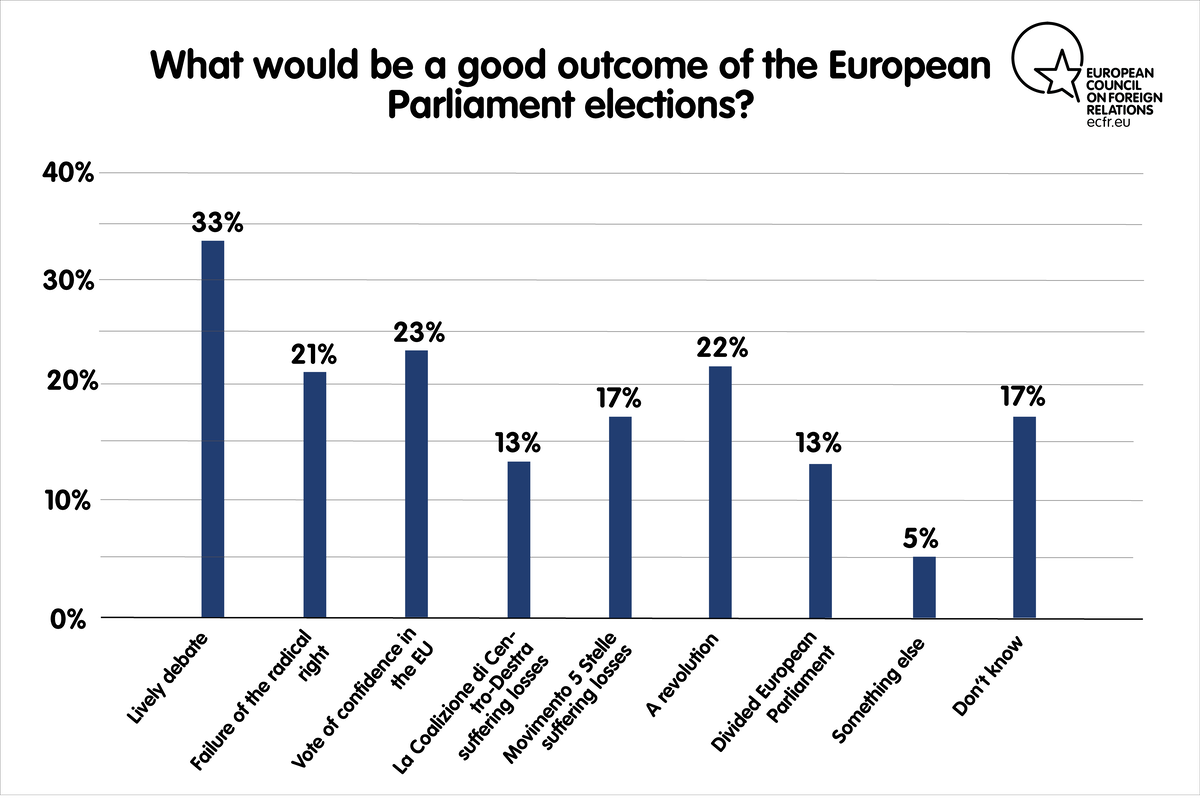

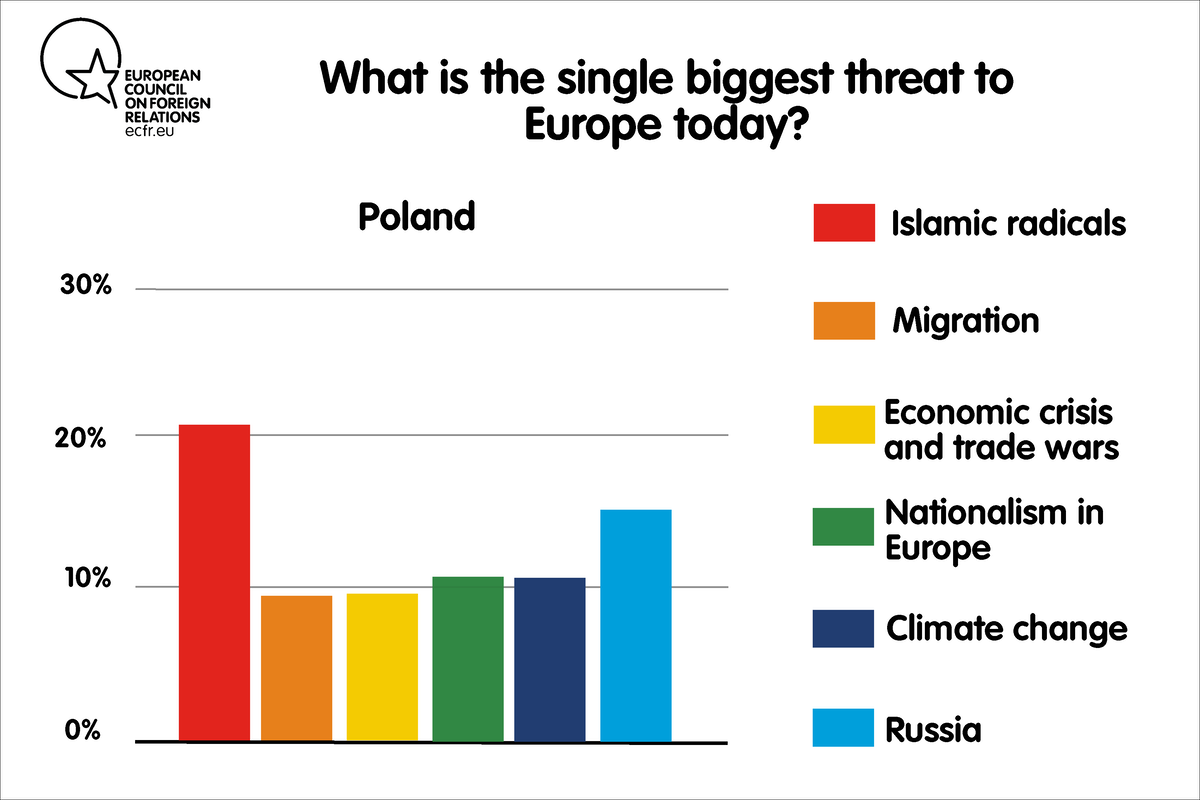

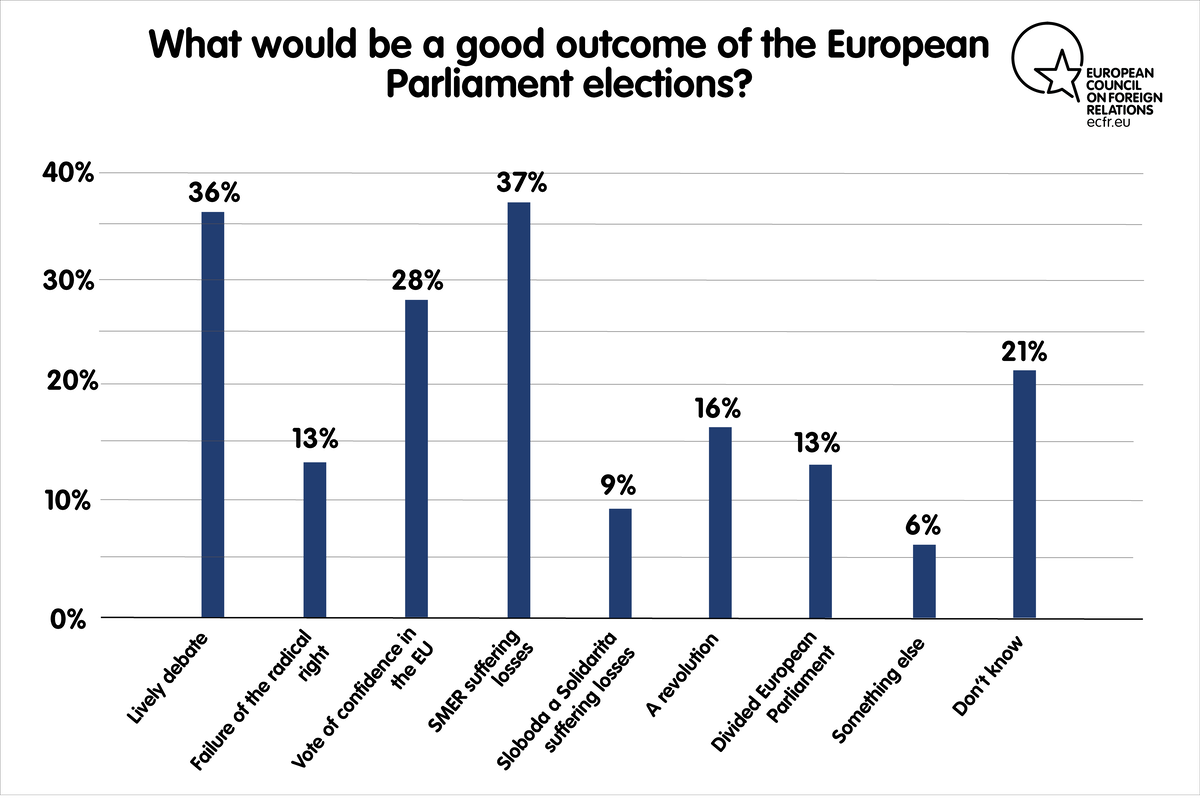

But the study findings show that the world of 2019 is radically different to that of 2015. The poll asked voters what they think the biggest threats to the EU are; what issues are of biggest concern to them; and what would constitute a good election result.

The campaign for a ‘fortress Europe’ will not be winning strategy, for three reasons.

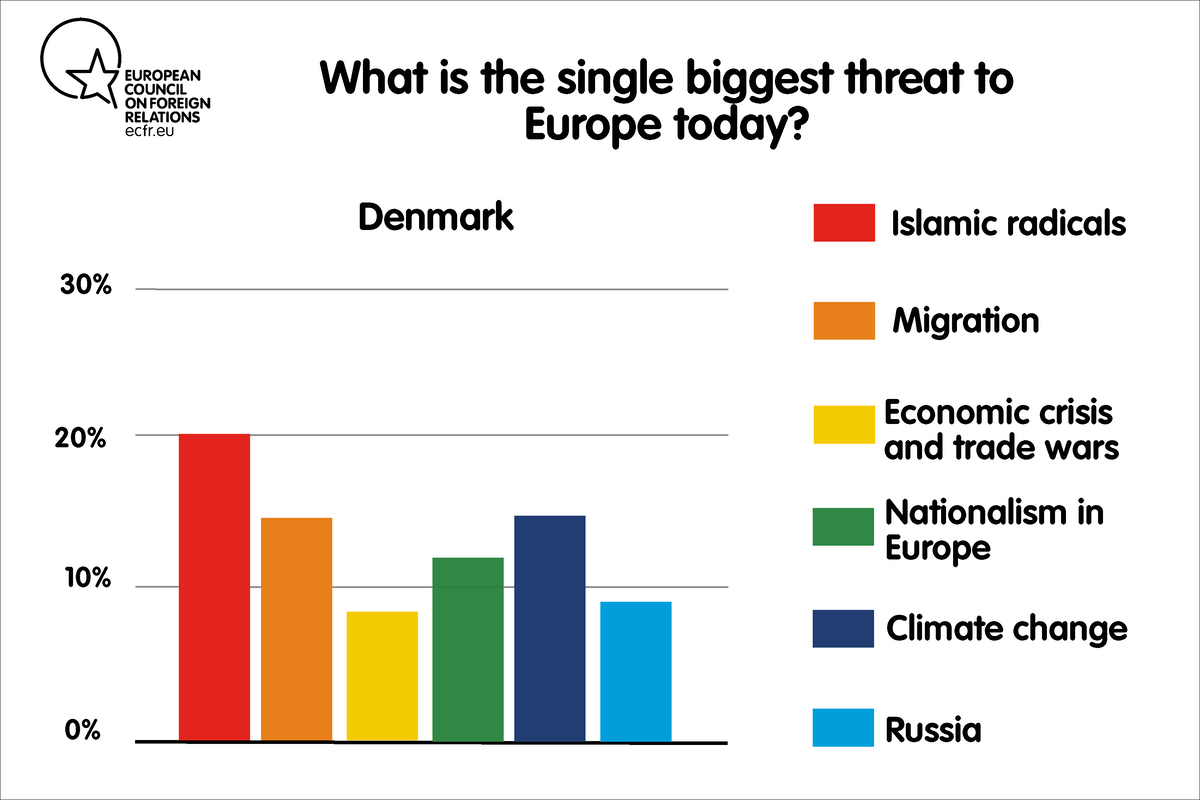

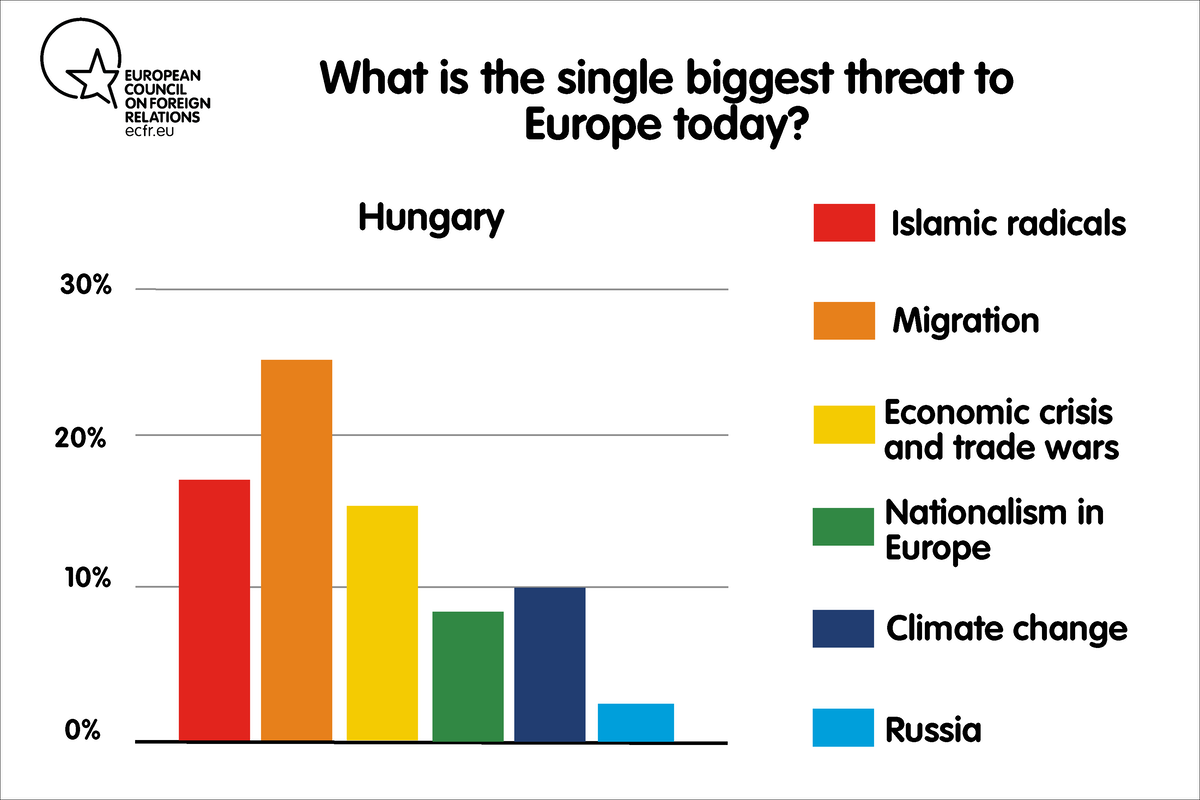

Firstly, migration is not a defining issue. The survey results show that a majority of people in every single country polled do not regard it as one of the top two issues facing their country. Hungary is the only country where immigration is still felt to be the number one threat to the EU. This is little wonder given the endless stream of propaganda that Orban puts out through his state-controlled media. But in every other one of the 14 countries polled one of at least five other themes emerged that are equally, if not more, important to Europeans. Rather than being a referendum on migration, this election will see European voters make up their minds on six thematic European election issues – with migration not among them.

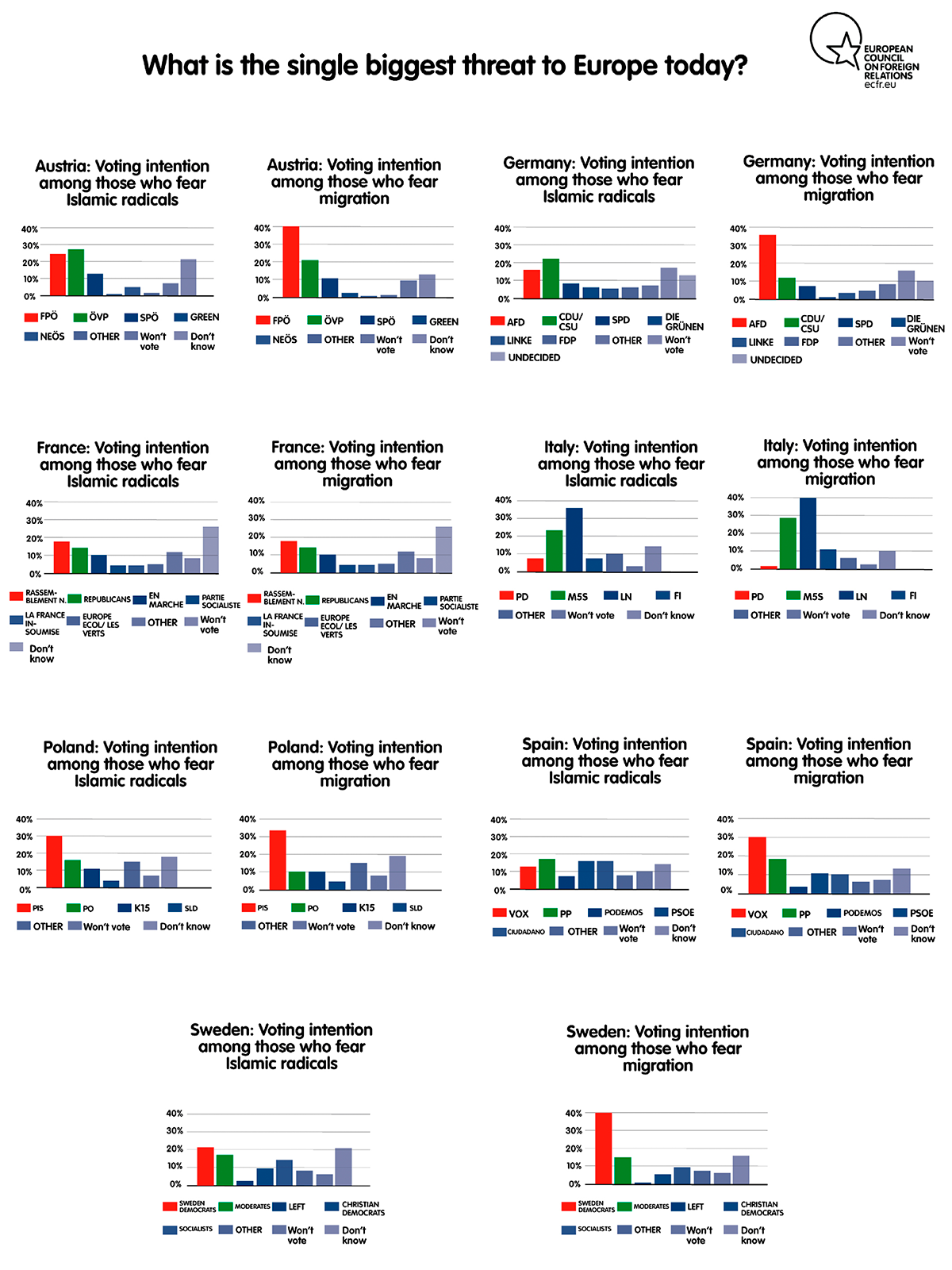

The poll reveals that the more Europeans fear Islamic radicalism than any other threat. But this does not automatically mean that a political party adopting an anti-migration posture will sweep up such voters: Islamic radicalism is a far greater preoccupation among voters who align with centre and centre-right parties than among anti-system parties, which are far more concerned about migration and the number people arriving in Europe. Those who oppose migration, meanwhile, are more likely to support far-right parties such as Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), Rassemblement National, and the Freedom Party of Austria. Notably, Islamic radicalism is the highest concern for voters who identify as Catholic or Protestant – implying the importance of integration and social cohesion policies as a response for these voters – whereas nationalism is the largest concern among atheists.

Another important issue that is squeezing out migration is the fear that nationalism will destroy the EU. Voters see this as more important than – or at least equal in importance to – migration in Austria, Denmark, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain. Nationalism is especially important to voters who say they are likely to turn out.

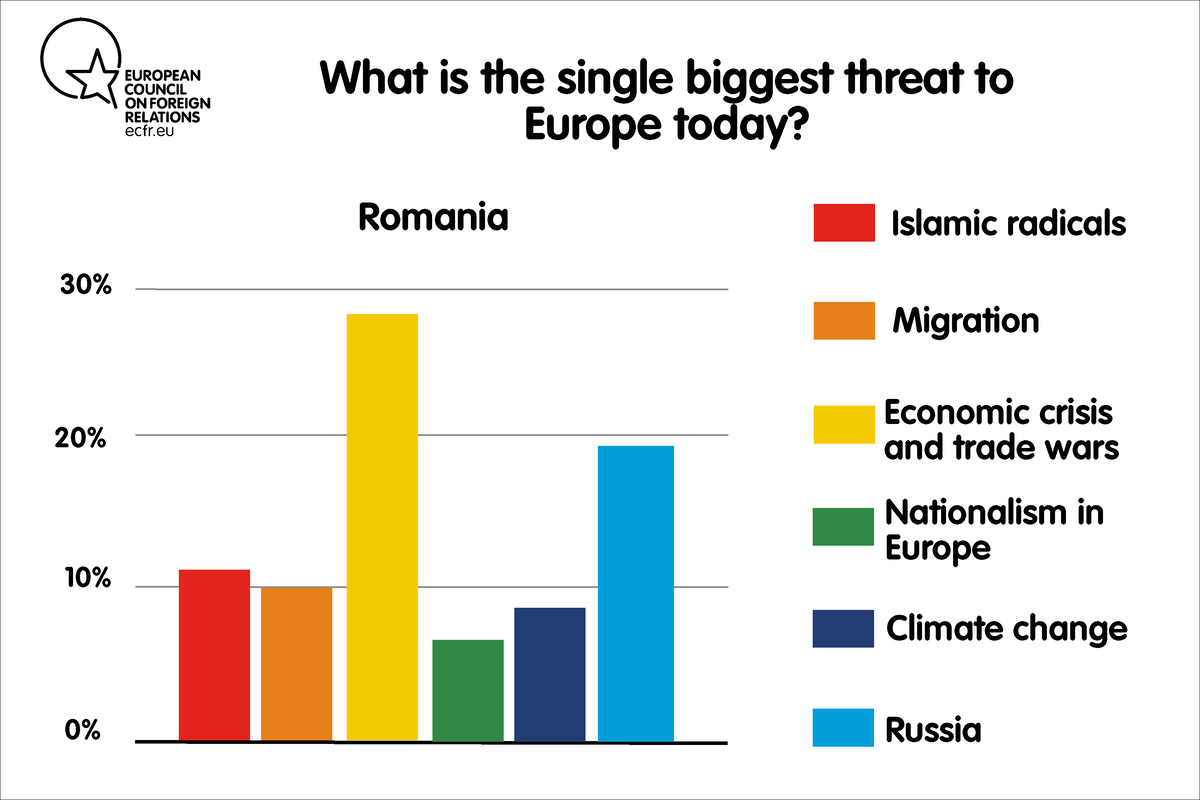

In Italy, Romania, Greece, and Slovakia, the economy is a hugely prominent issue. In every member state, apart from Denmark and Germany, a minority of voters think their economy is performing well.

One big surprise is climate change. Only Danes cited this issue as one of two top threats among others. But, when asked about it as a standalone issue, climate change polled spectacular majorities across all 14 countries. Finally, Russia is a leading concern in Sweden, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Romania.

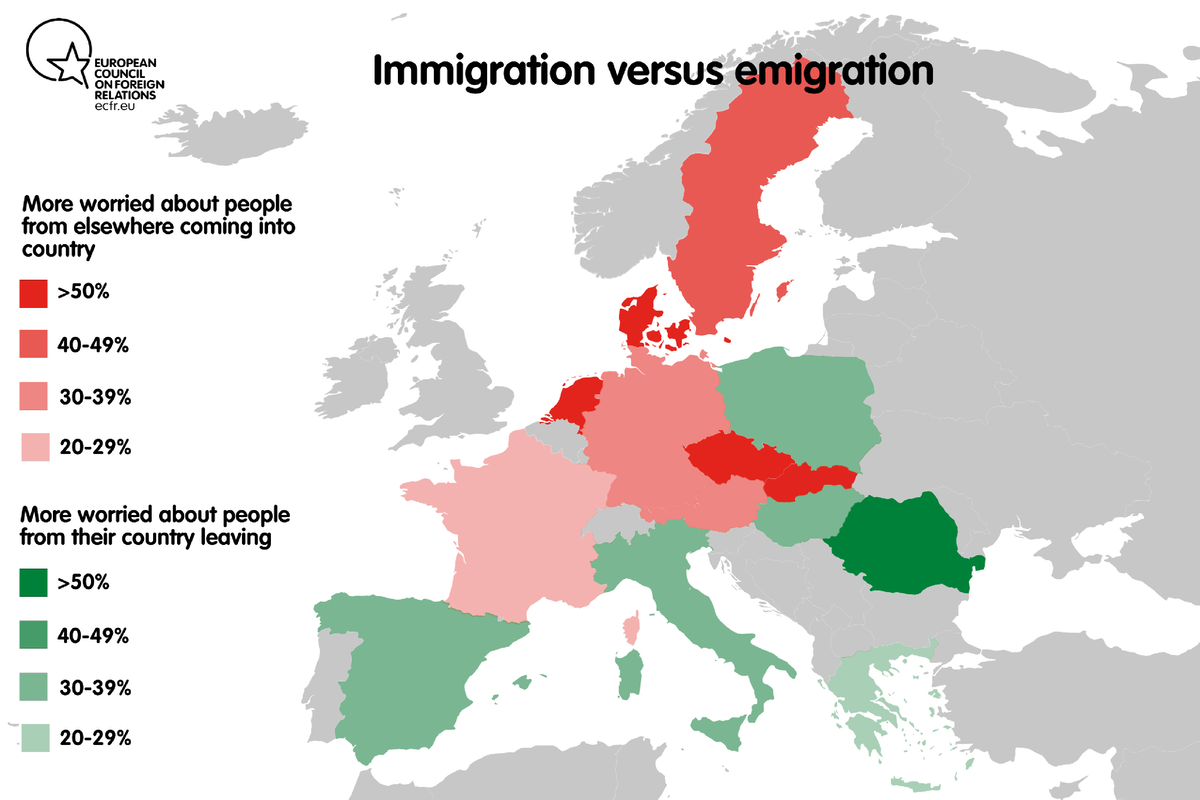

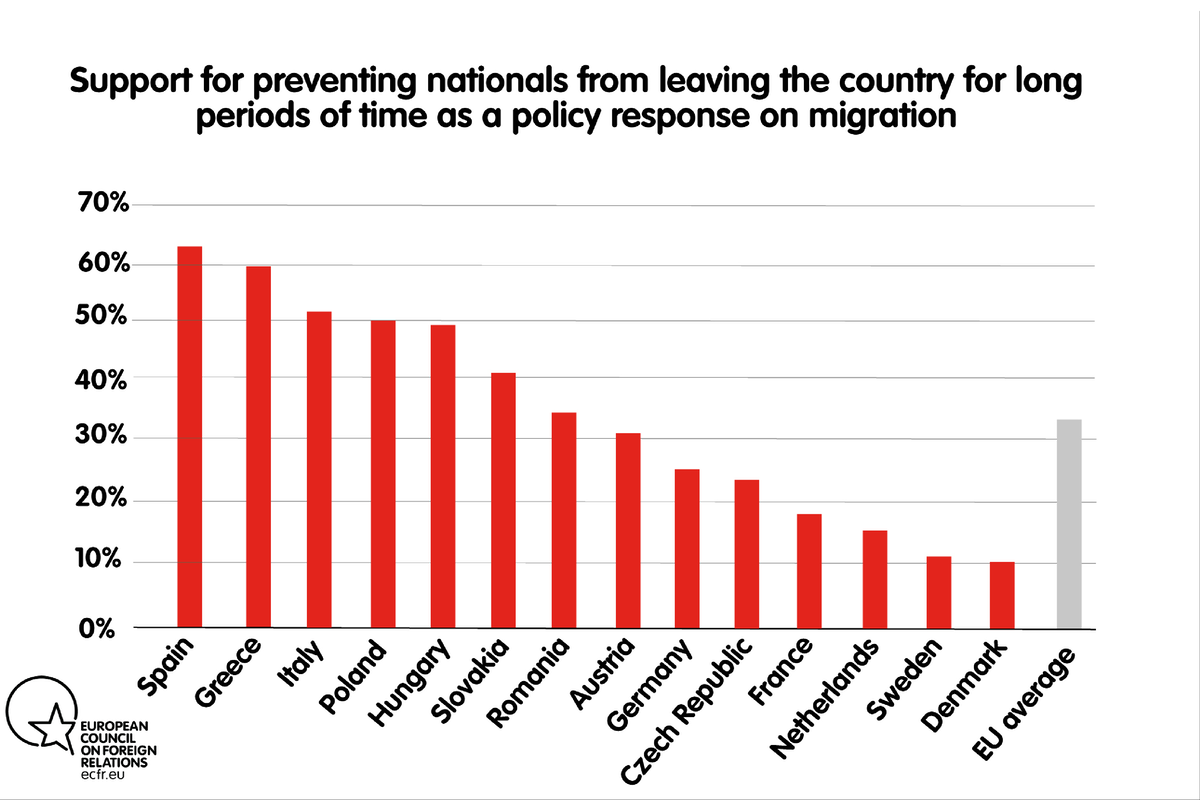

There is a second reason migration is unlikely to work as a key driver of turnout at this year’s election: even those who see migration as a top issue mean radically different things when they talk about it. In some countries, respondents likely associated “migration” with emigration rather than immigration. Indeed, our research revealed a significant divide between those who worry predominantly about immigration in their countries and those who worry about emigration leading to a decline in the national population. While northern and western Europe still fears the inflow of outsiders, majorities in Greece, Italy, Spain, Hungary, Poland, and Romania are much more worried about their citizens leaving. This leads to the spectacular finding that double-digit majorities in all these countries would like their governments to make it illegal for their own citizens to leave for long periods of time. In a Europe that prides itself on tearing down borders and promoting free travel, such a desire for self-imprisonment is striking. In Romania, one in five citizens has left their country in the last decade. Those left behind seem ready to create a new migration wall for themselves – just three decades after the Berlin Wall fell.

Crucially, our analysis shows that concern about migration is much less of a driver of willingness to vote than other policy areas of concern, such as fear of nationalism. Migration does not particularly stand out from other fears as a driver, such as worries about the economy, the ageing population, or climate change.

This may reflect some of the big changes in politics since 2015. The most obvious one is the collapse in the numbers of arrivals: television screens are now more likely to be occupied by the chaos of Brexit than uncontrolled borders. It is also a reflection of the fact that all mainstream parties now advocate stronger controls on the EU’s border – and none of them advocates open borders.

This does not mean that mainstream parties should be silent on migration – saying something credible on this will be part of earning the right to be listened to on other issues. But they need to go beyond talking about border controls to engage with fear of Islamic radicalism and the brain drain affecting many European countries. They should develop an agenda around security and the integration of migrants that is sensitive to national and regional differences, and that addresses cultural anxiety, policing, and intelligence, as well as questions of citizenship and language.

This is a huge challenge, but tackling it could help normalise politics in countries focused on emigration and immigration alike. That would be the ultimate blow to Orban and Salvini – and might even convince Bannon to pack his bags and permanently return to the US.

Myth 4: The dividing line in Europe is between east and west

The truth: East and west are not homogeneous, and there are important differences between, and within, north and south

Reportage on Zuzana Caputova’s election as Slovakia’s president in March 2019 portrayed her as a progressive anti-corruption lawyer and acclaimed her for halting a populist march across central and eastern Europe. Underlying this was an enduring myth that eastern member states are fundamentally less favourable to the values set out in Article Two of the Treaties of the EU than those in western Europe. ECFR’s and YouGov’s polling shows that this supposed division does not exist.

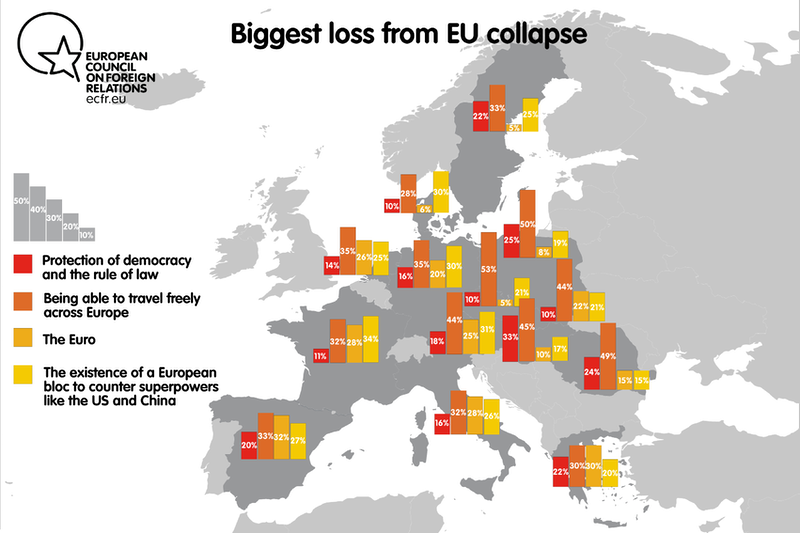

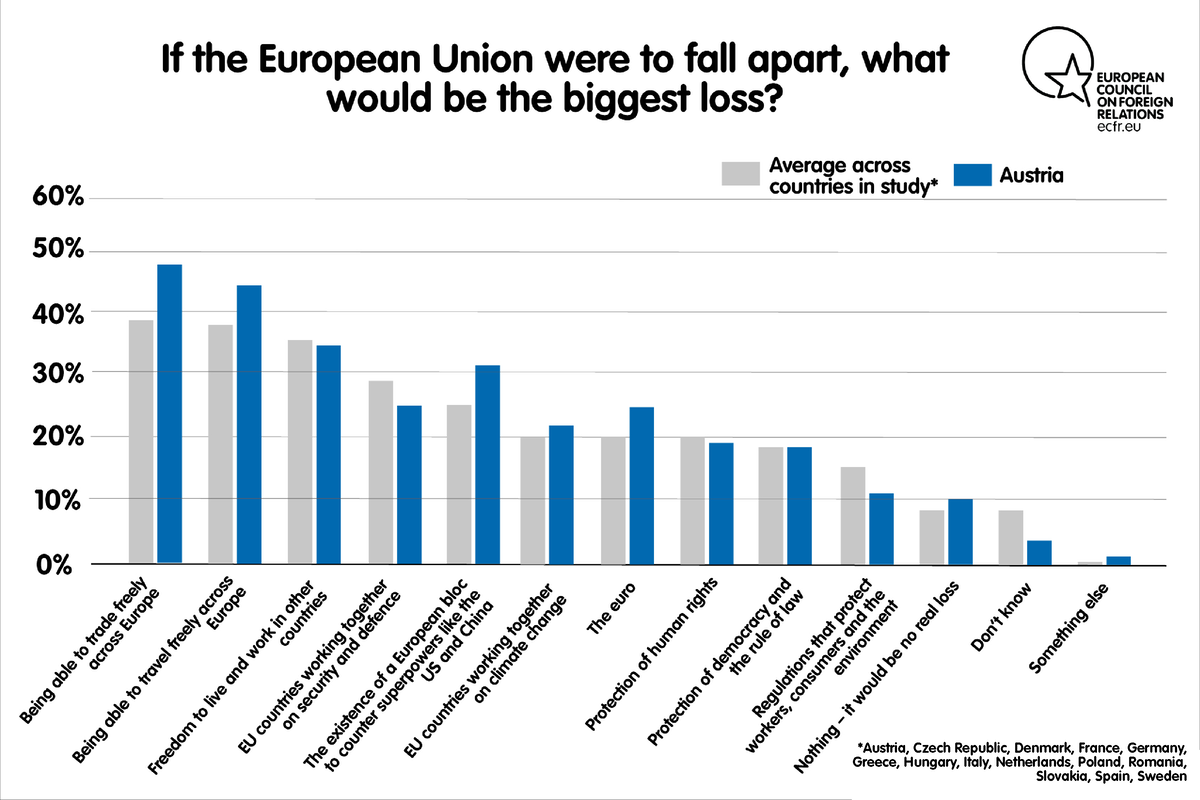

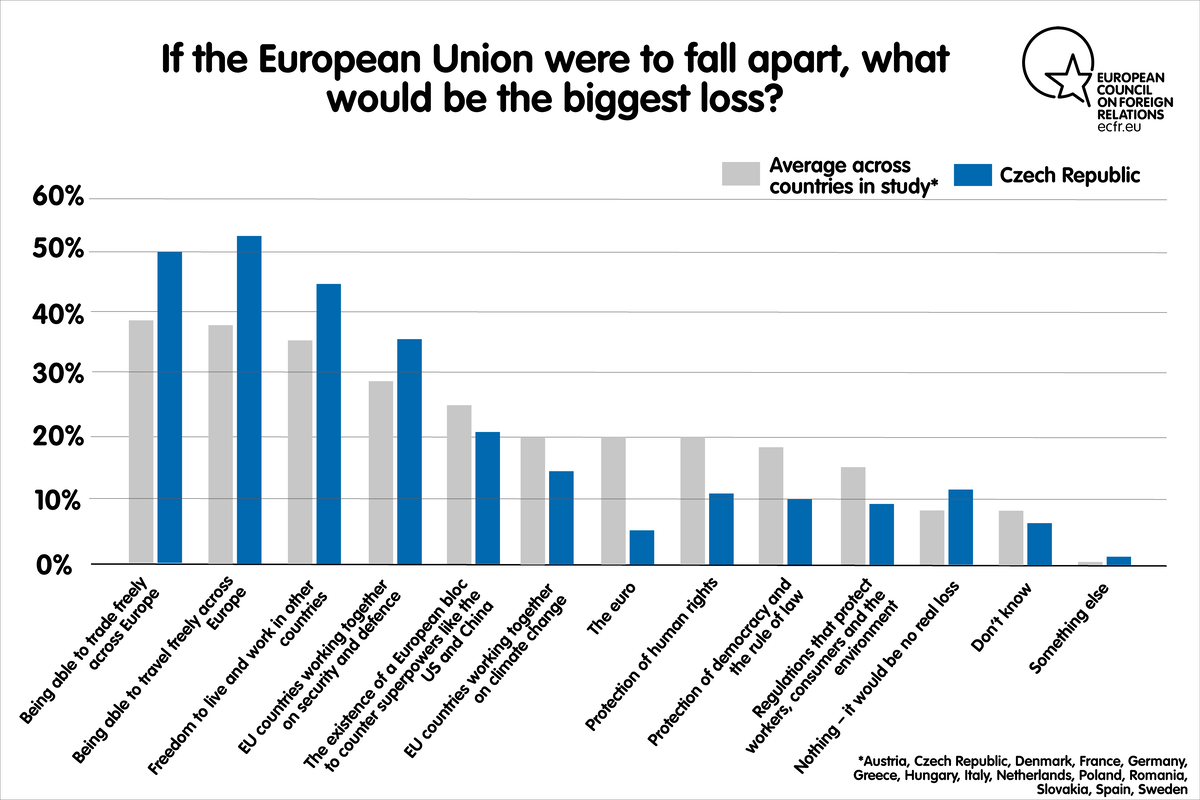

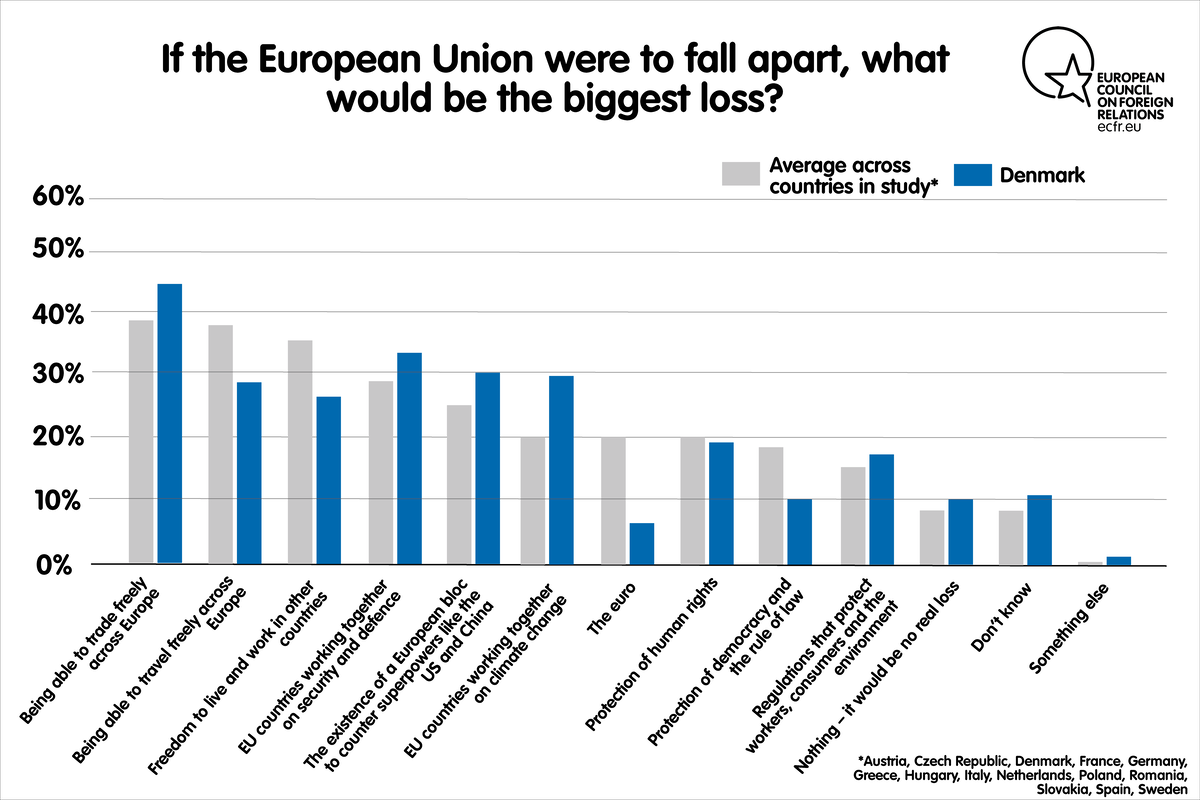

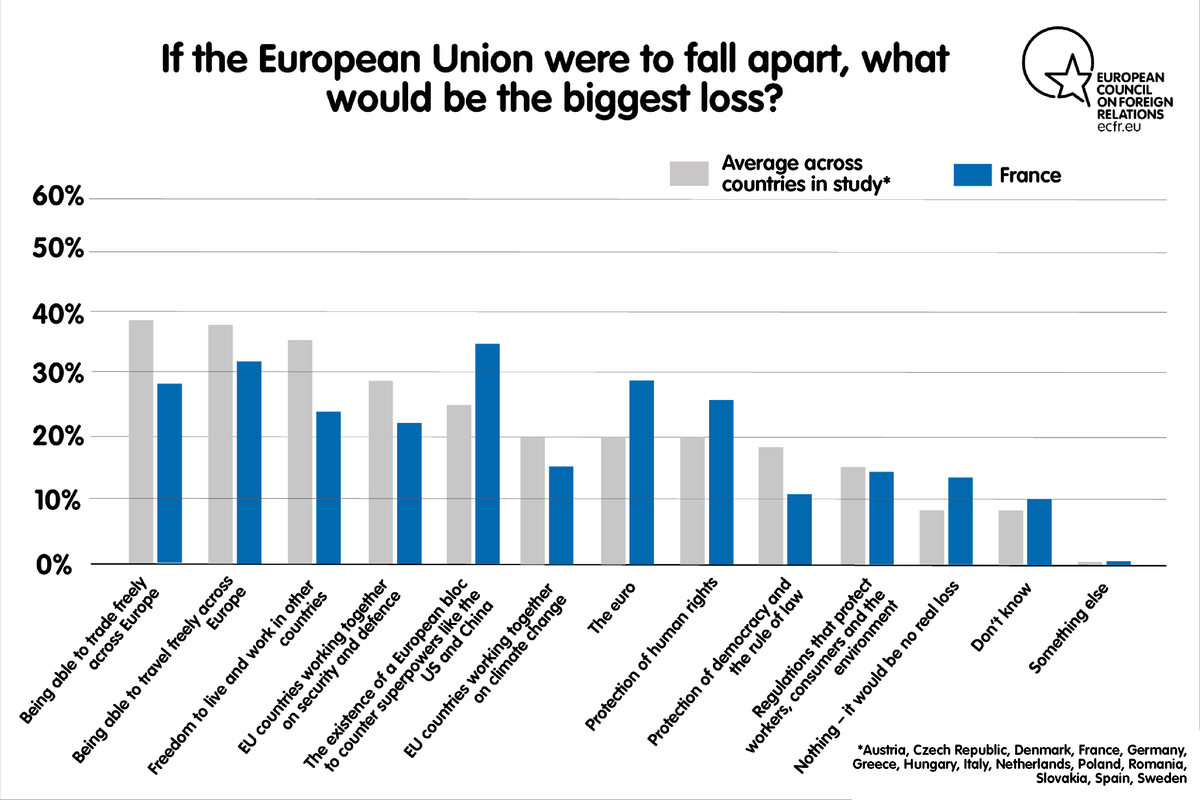

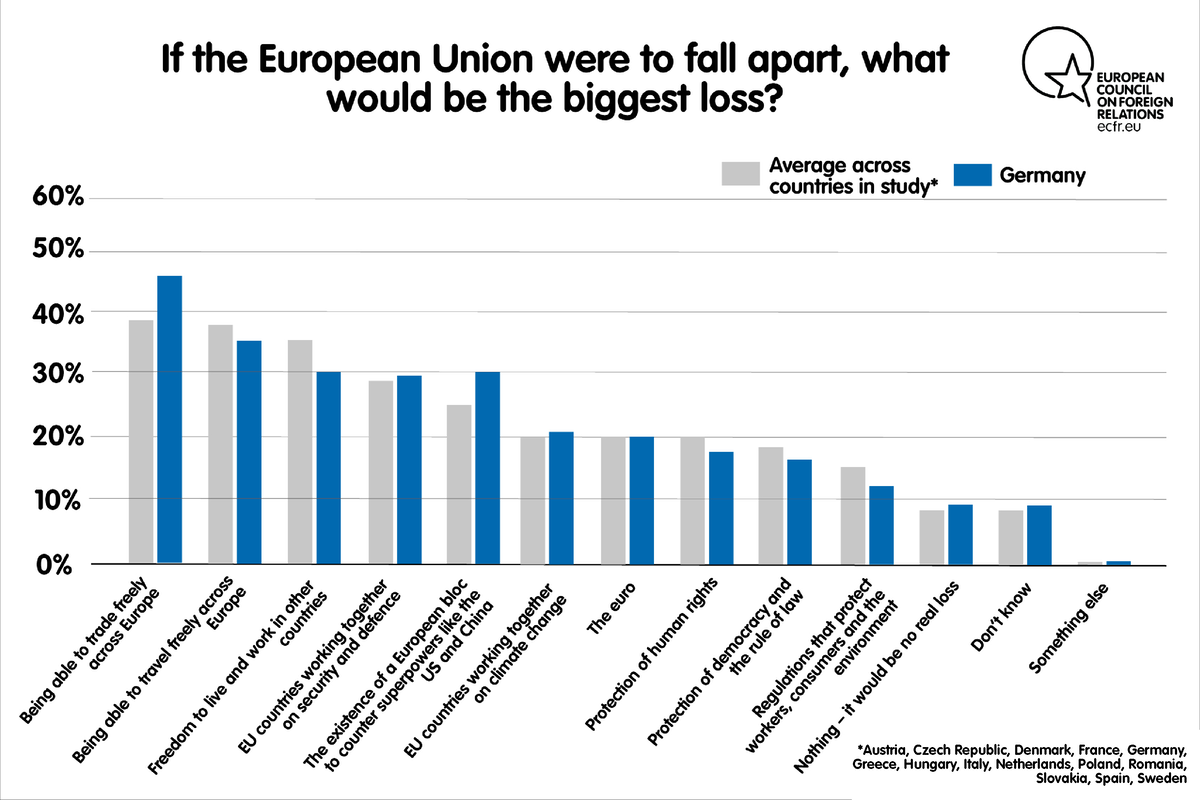

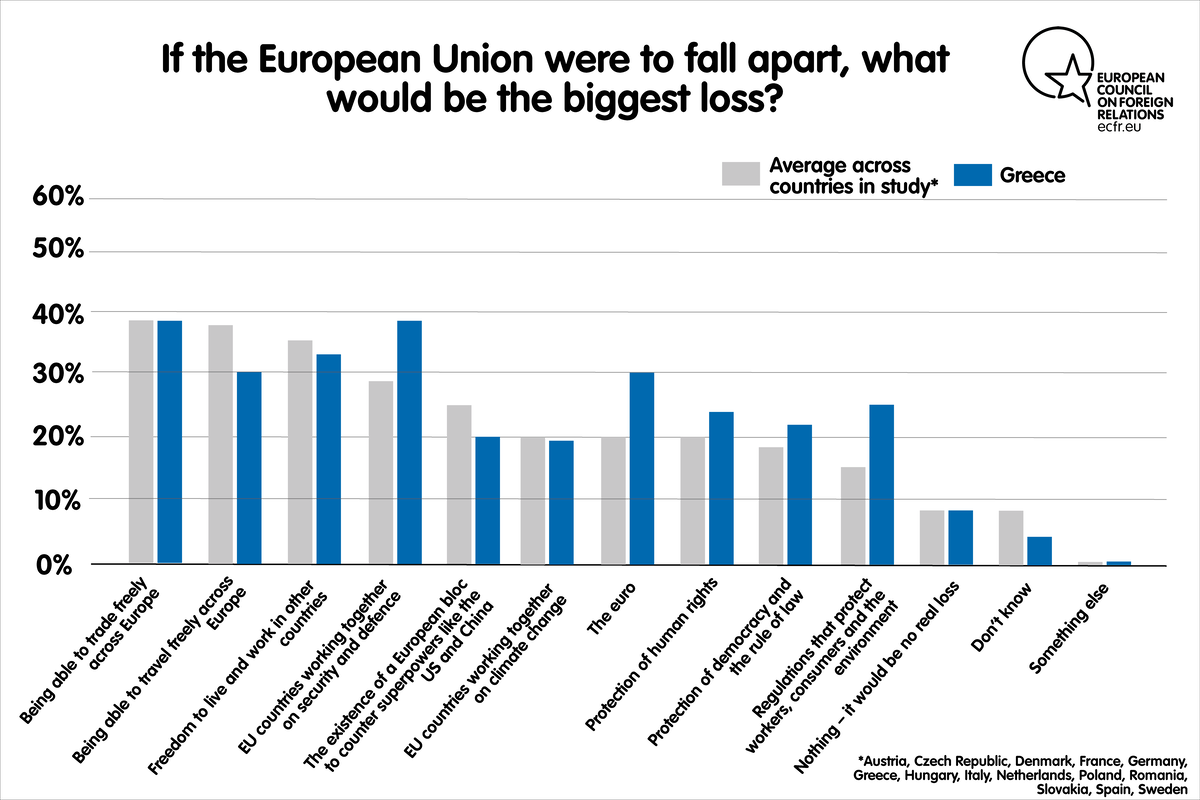

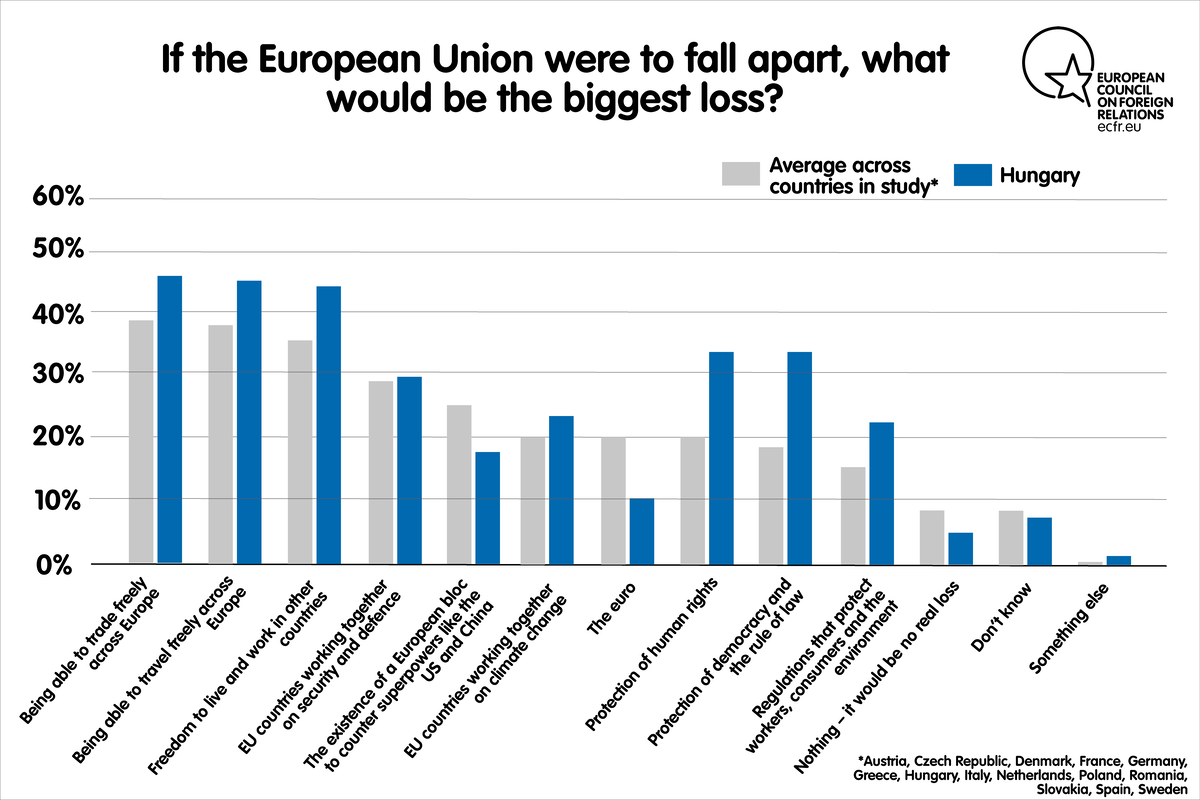

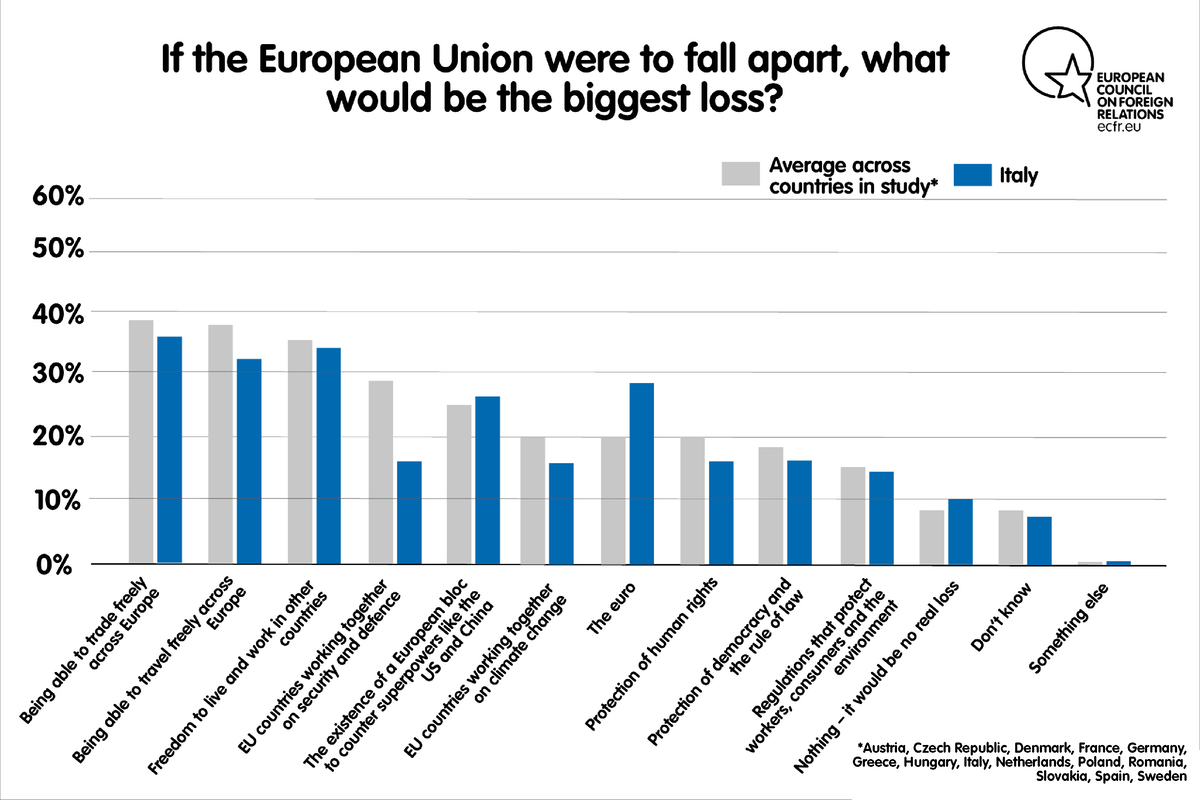

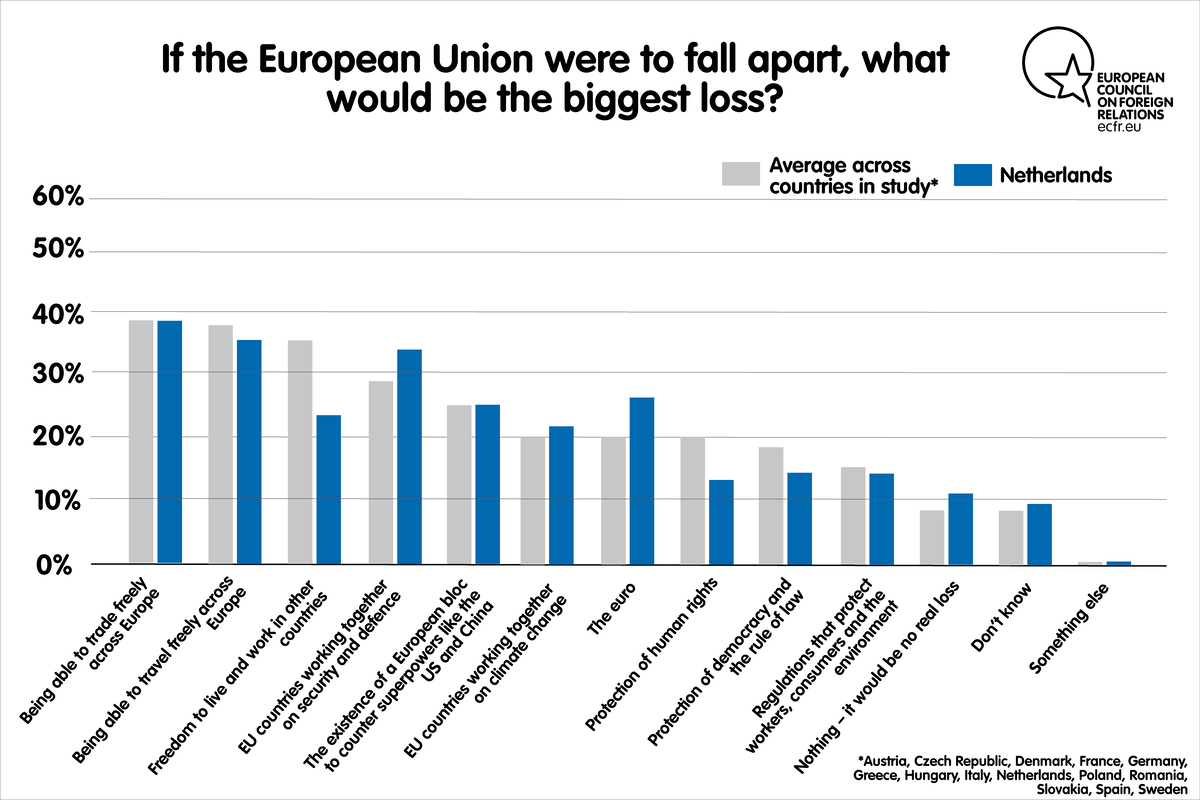

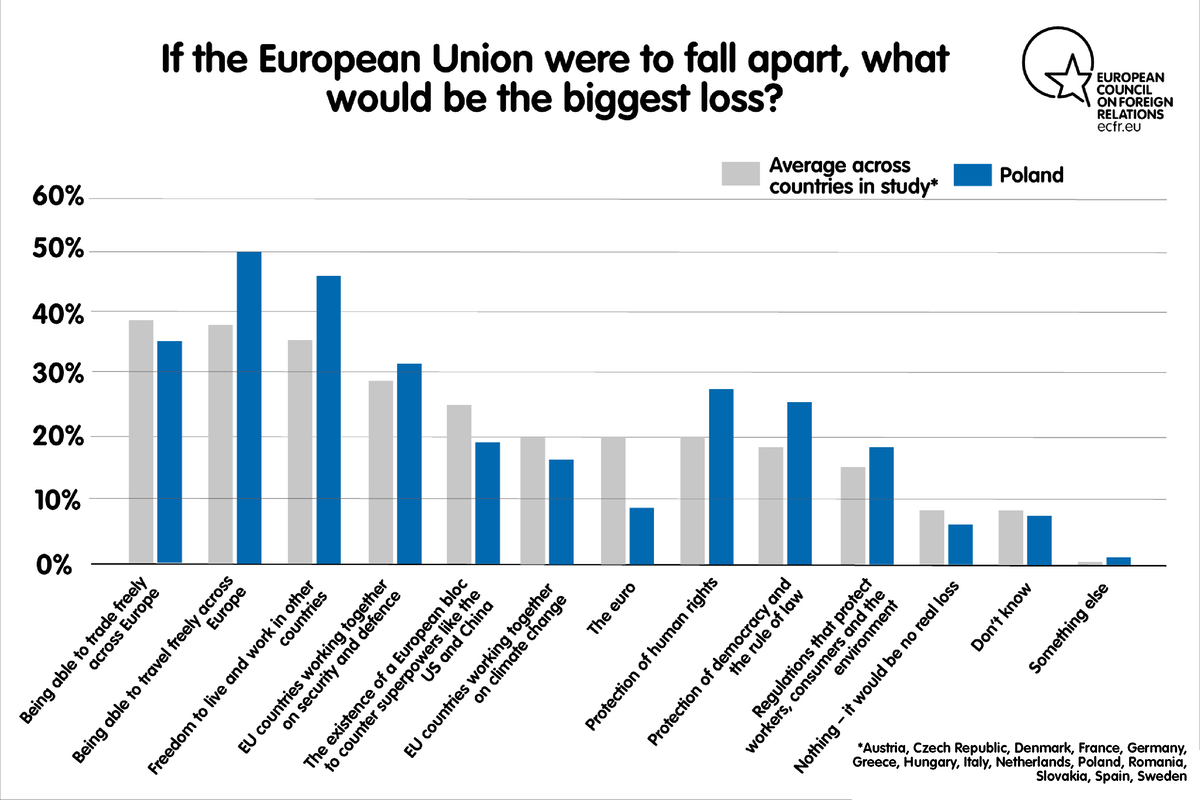

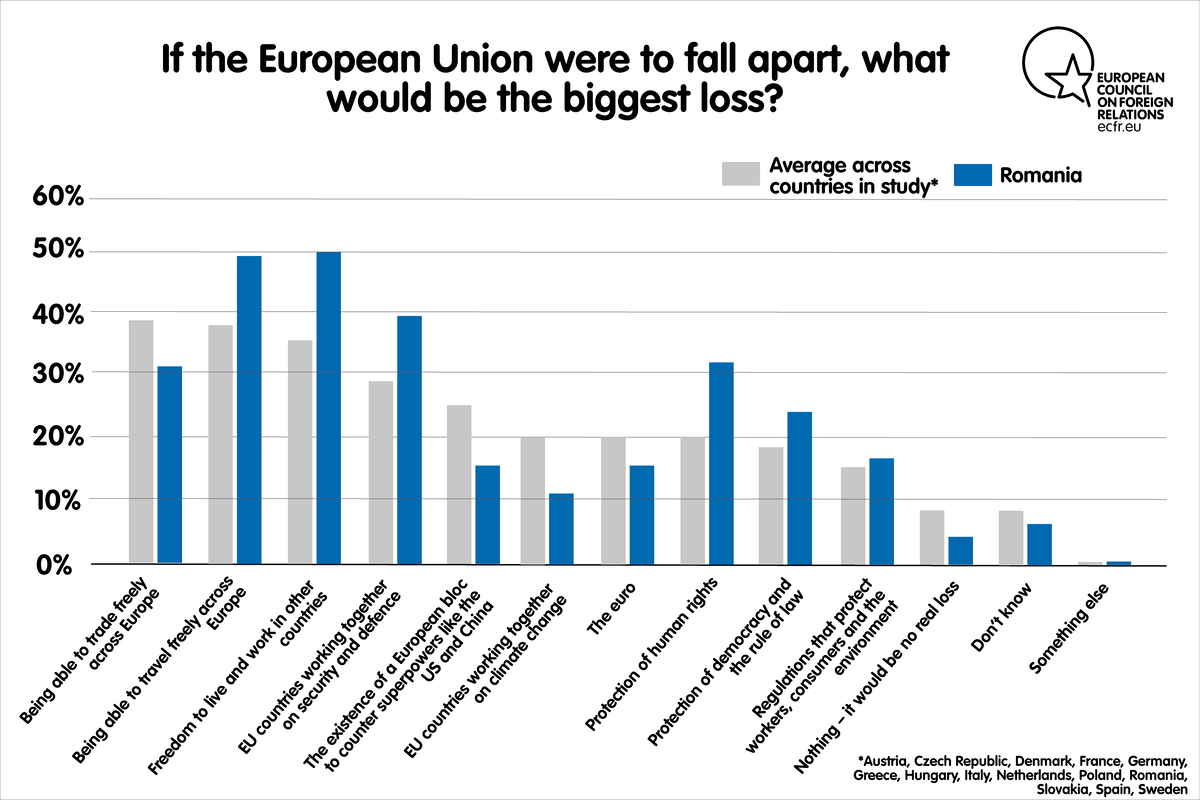

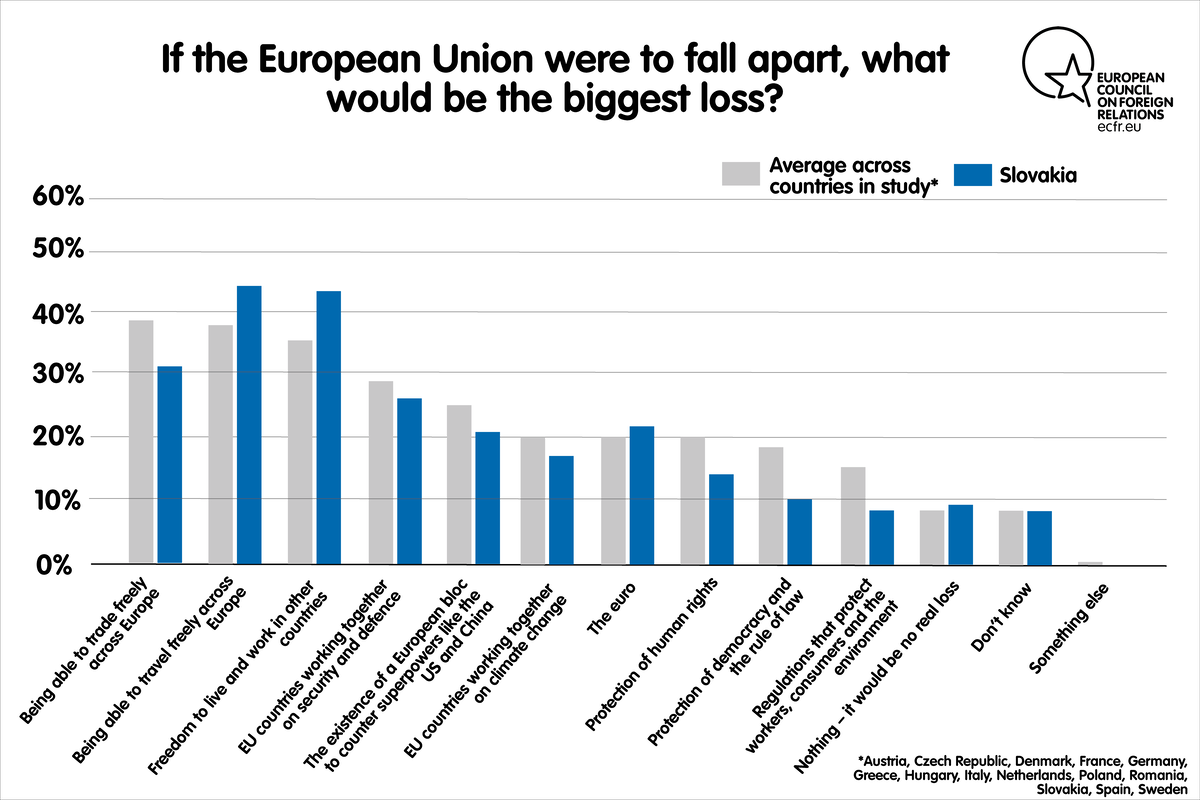

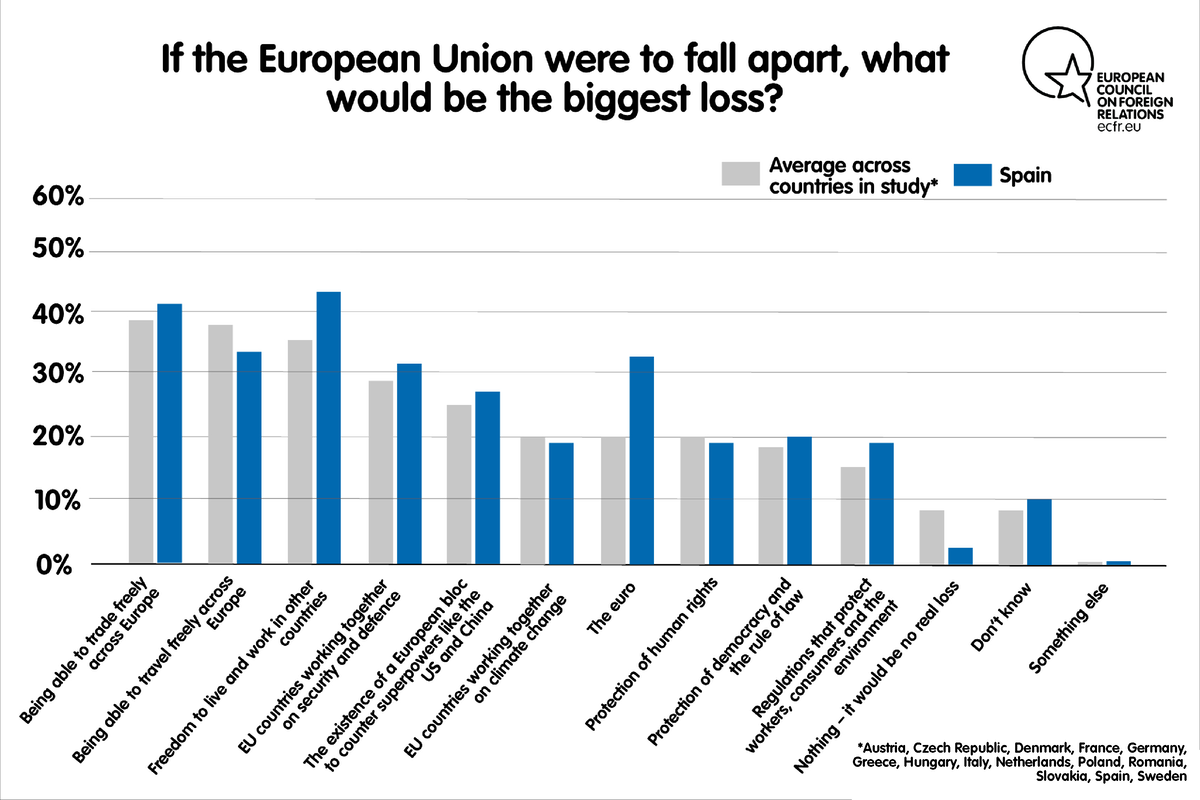

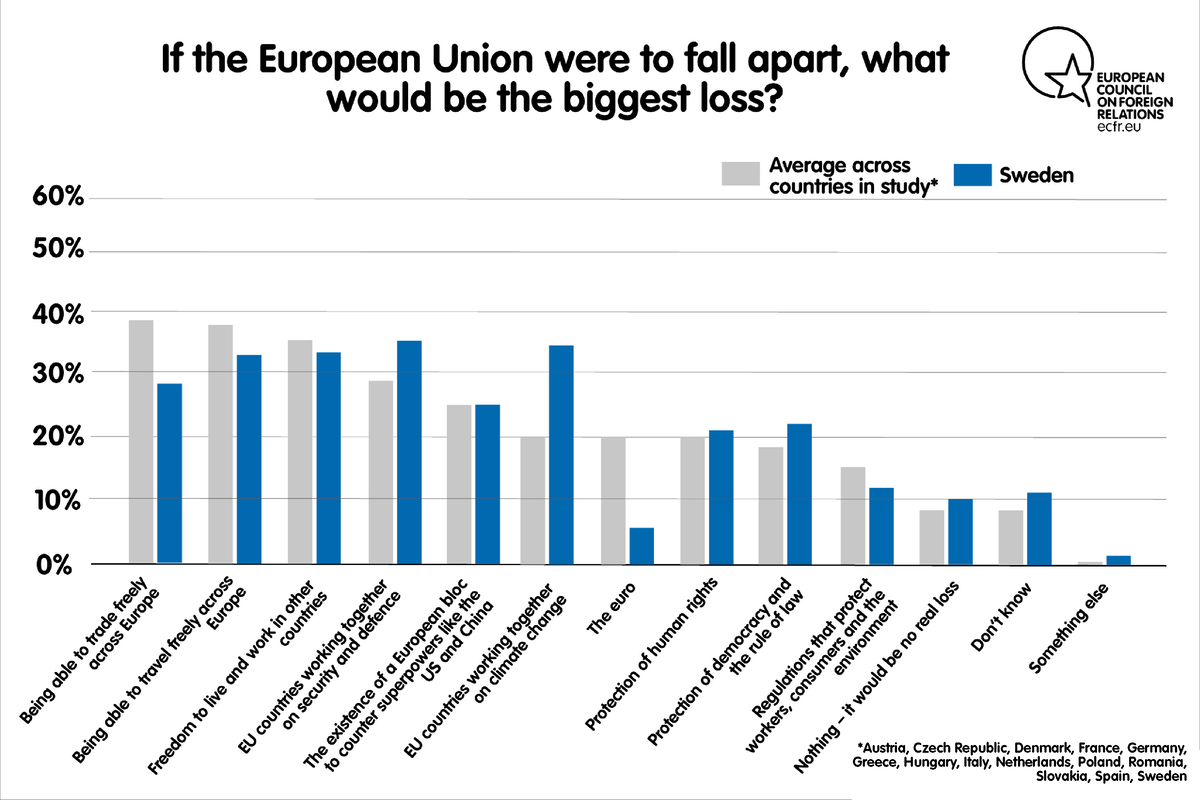

When asked what the greatest loss would be were the EU to fall apart tomorrow, the protection of human rights, and of the rule of law and democracy, were among the top answers across Europe, at 20 percent and 18 percent respectively. However, when this is broken down by member state, it is by no means just citizens in the west who are preoccupied with such issues. Thirty-three percent of Hungarians saw the loss of protection of democracy and rule of law as a major problem, compared to just 11 percent in France. On the protection of human rights, the figures were 33 percent in Hungary and 32 percent in Romania, compared to just 17 percent in Germany, 16 percent in Italy, 15 percent in France, and 13 percent in the Netherlands.

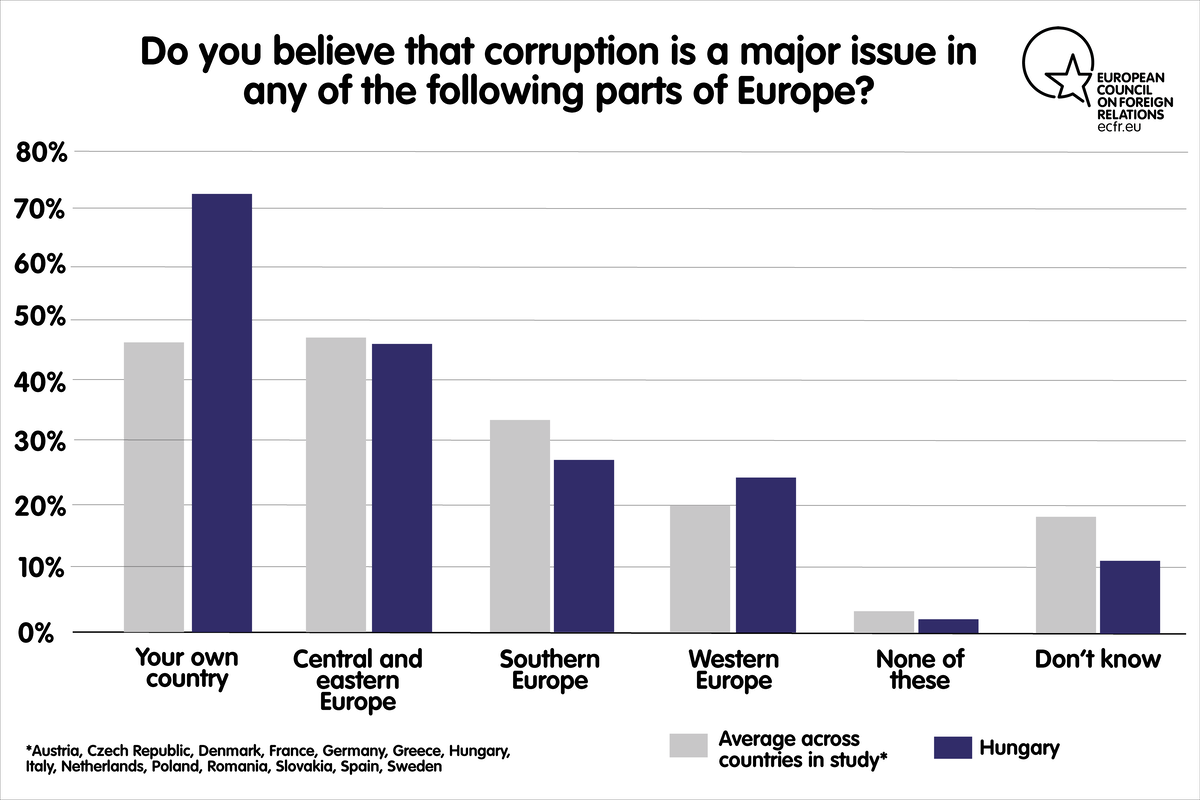

EU citizens in newer member states also seem less wary than their counterparts in older ones about the EU as a constraining force. This is perhaps explained by high levels of mistrust in corrupt national elites and weak national institutions in the east – meaning that they rate the EU higher by comparison. EU financial transfers may also play a role. And, when asked about the perceived consequences of EU membership, voters in Poland, Hungary, and Romania (along with Spain) were the most forceful in saying that EU membership protected against the excesses and failures of national governments. In other countries – including France, Italy, Germany, and Sweden – the most common responses were that the EU constrained national governments in doing what is best for its citizens. Citizens from the same group of states, along with those from Slovakia and Greece, also indicated that they are more likely to trust in the European Parliament to look after their interests than they are in their national governments.

As the political crisis in the EU peaked from 2015, growing coordination between Visegrad states (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) contributed to an image of these central and eastern European countries as more closed to newcomers, and less supportive of international commitments to protect refugees, than those in the west of the EU. In fact, the survey suggests that this image does not have strong underpinning either.

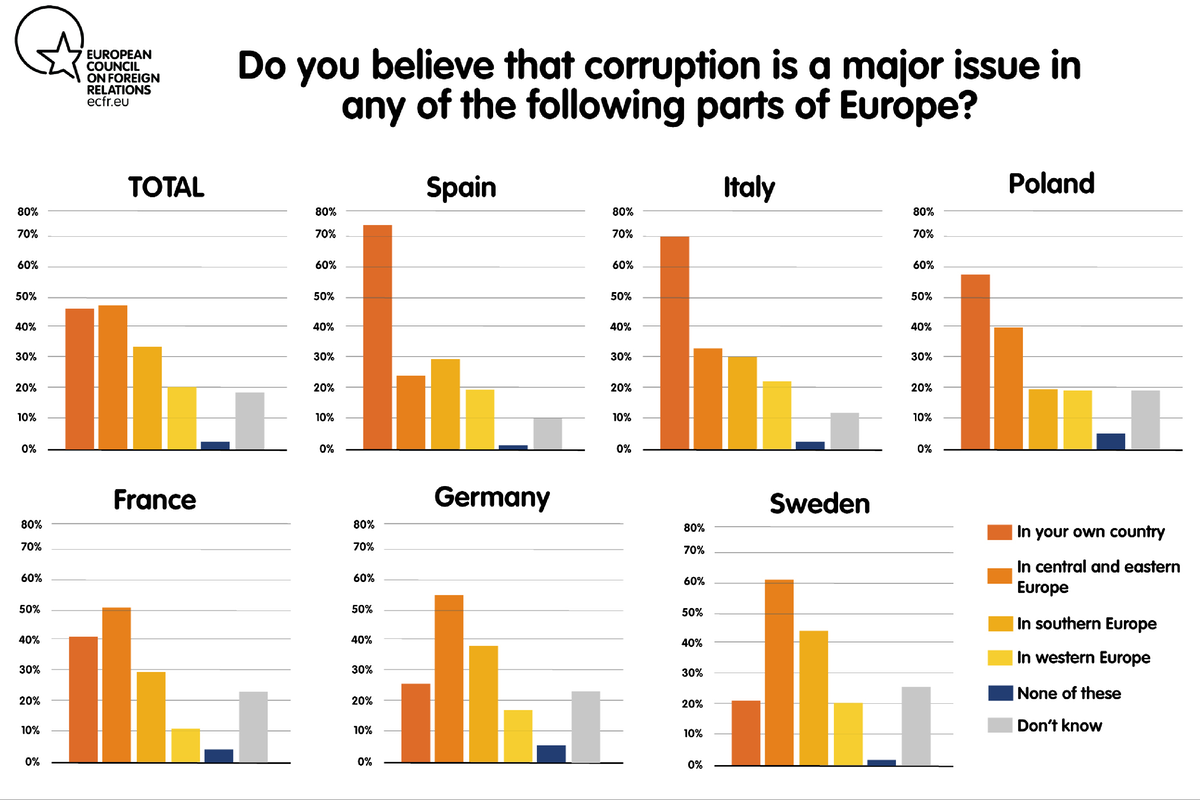

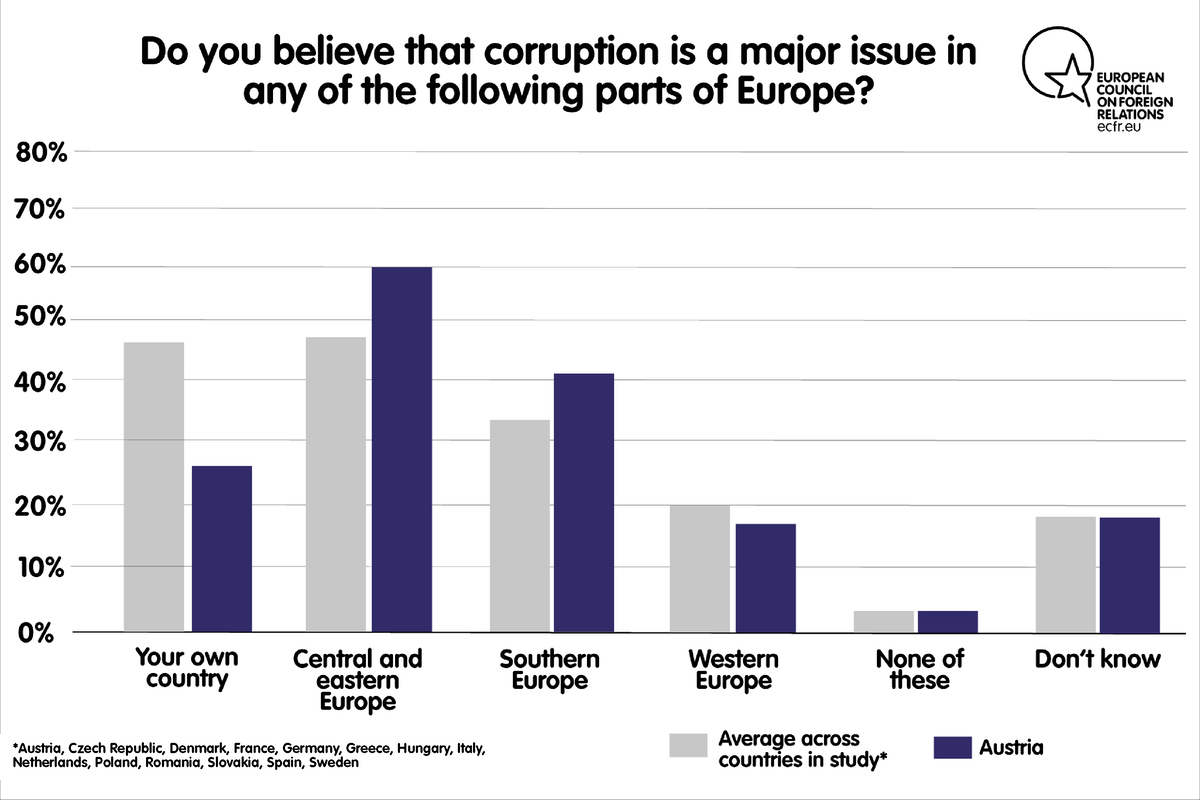

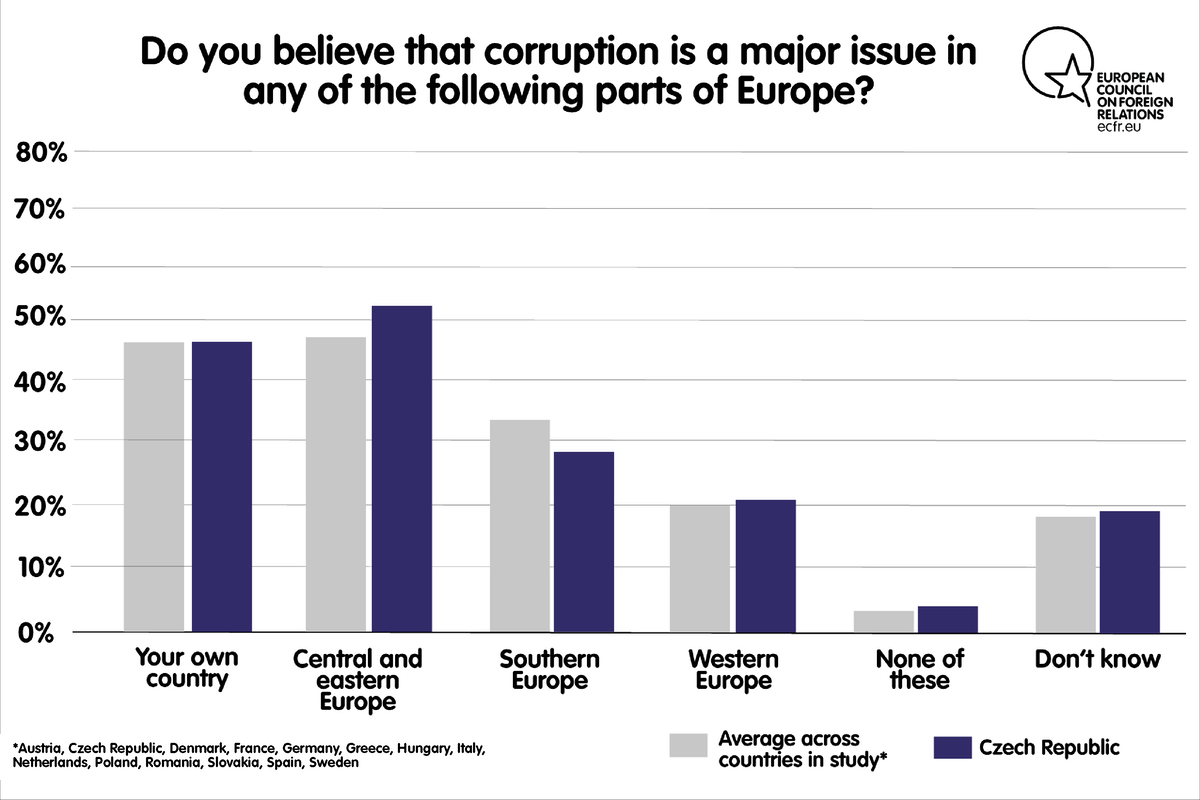

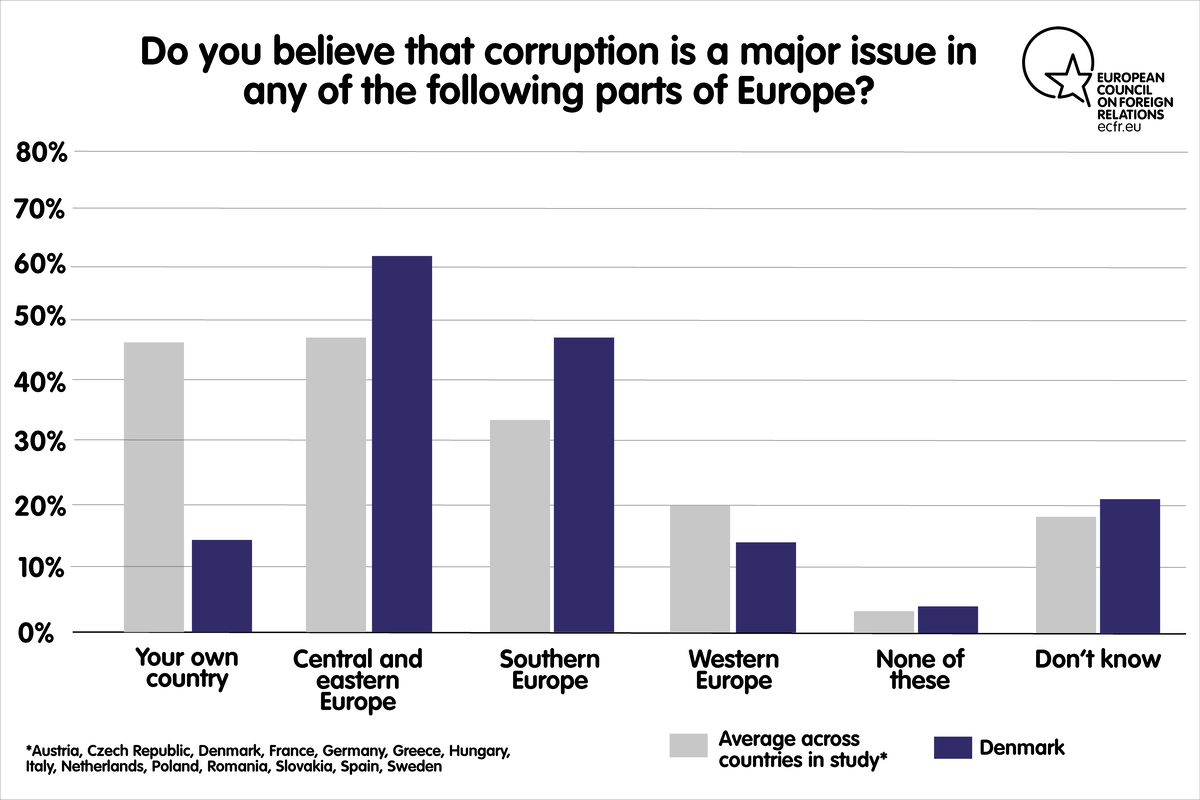

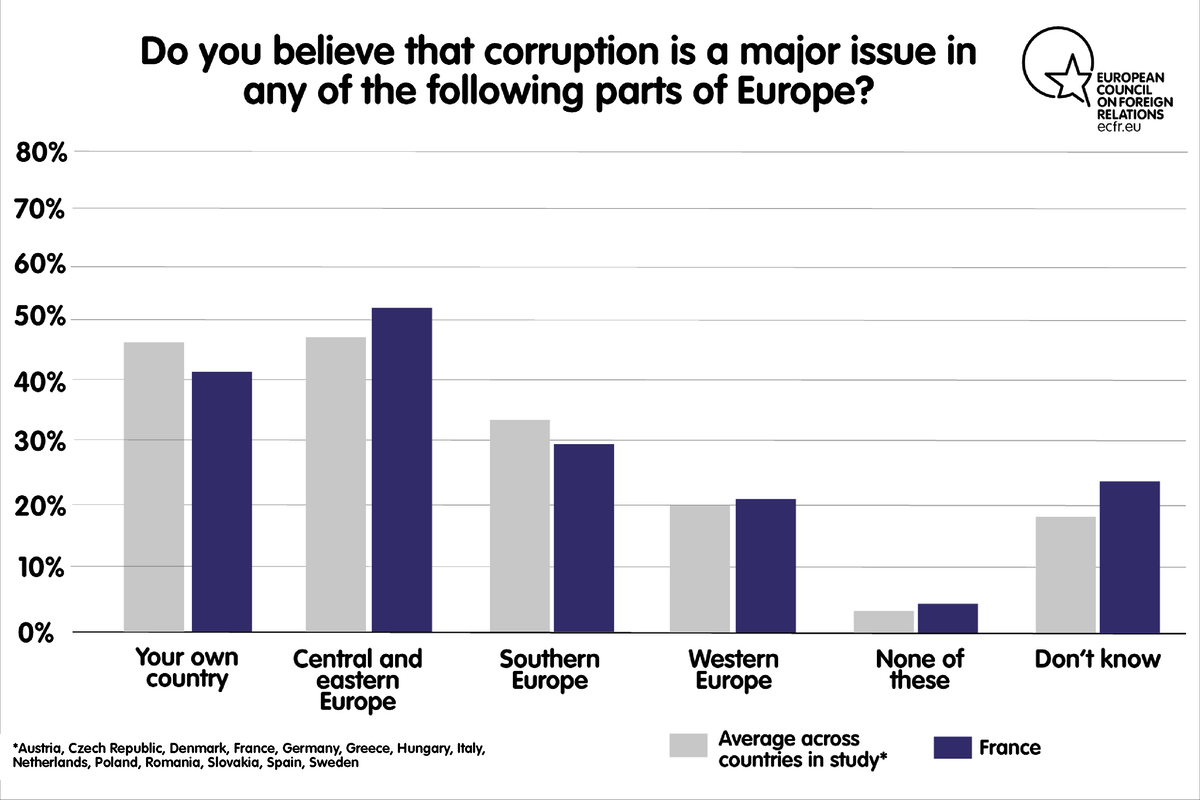

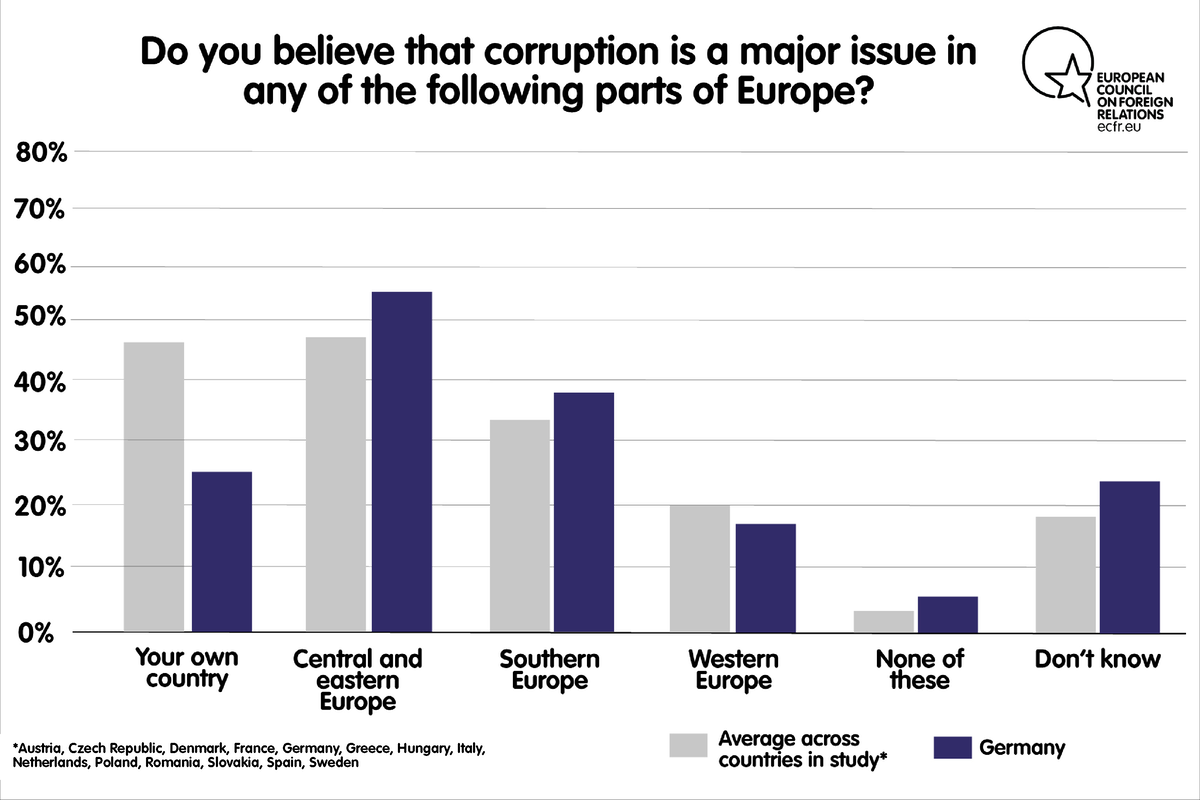

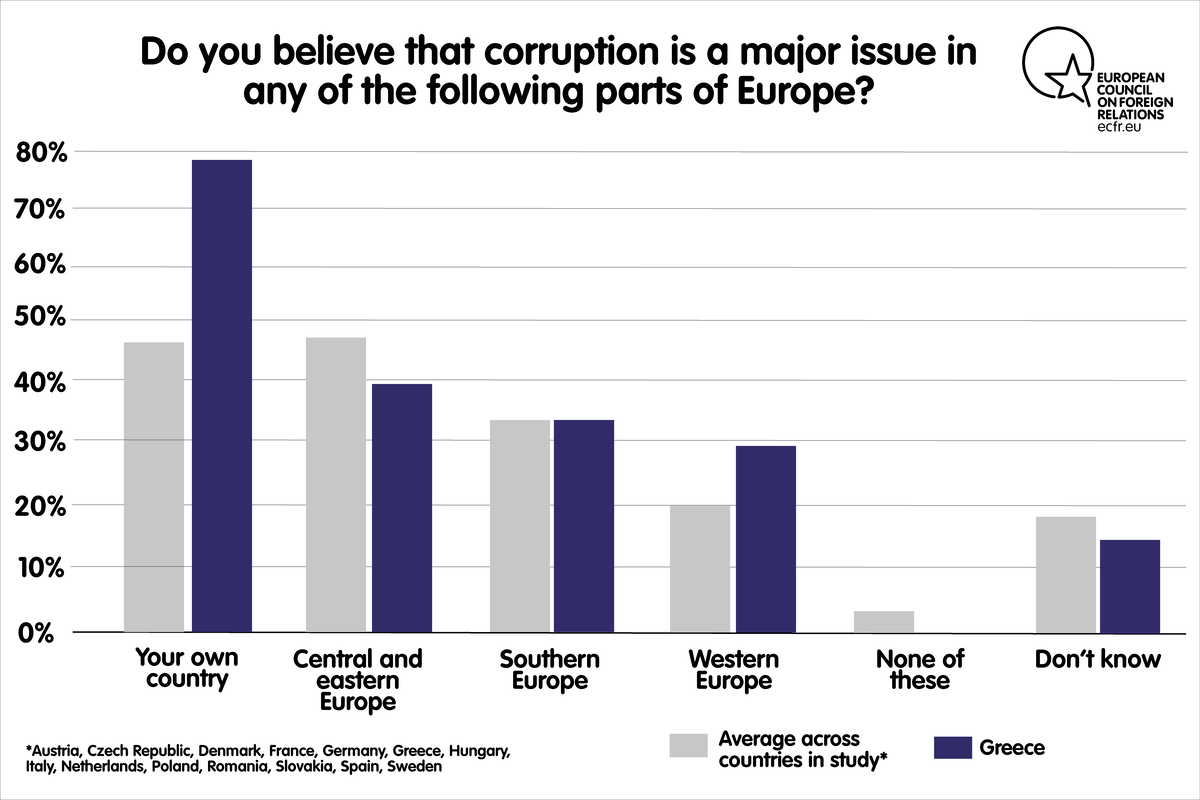

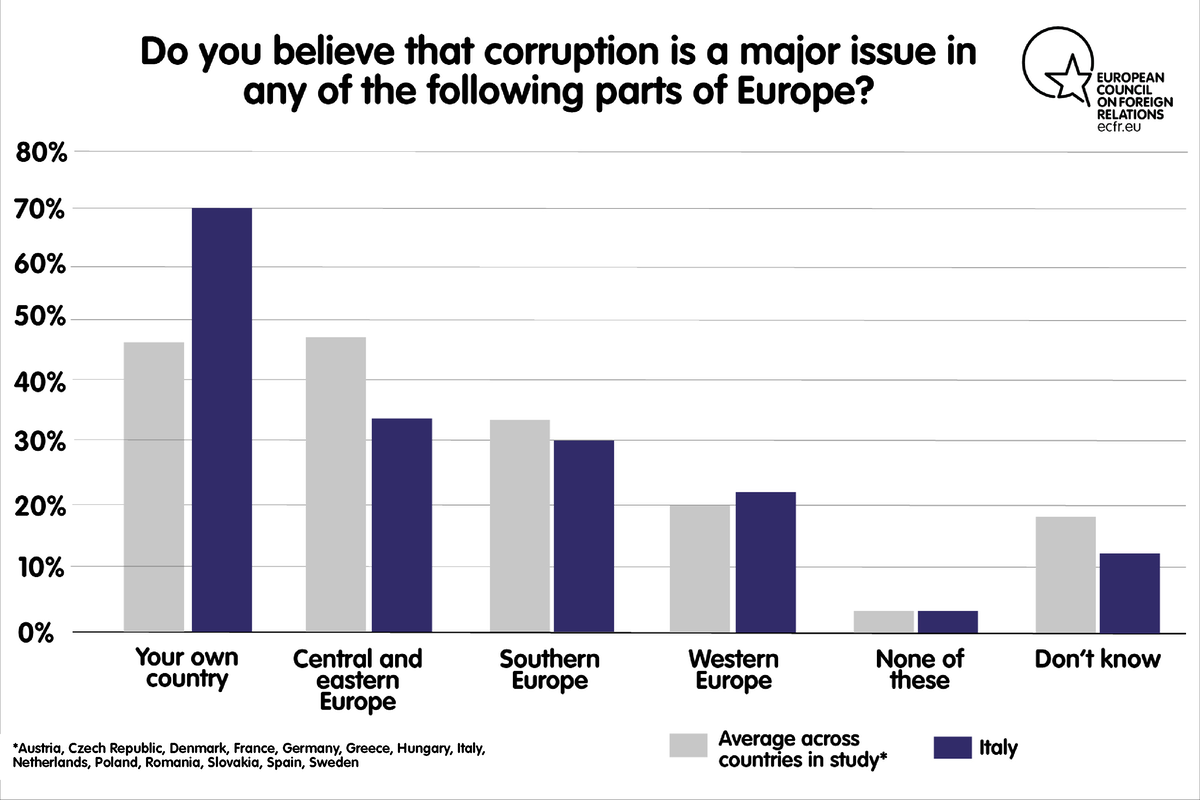

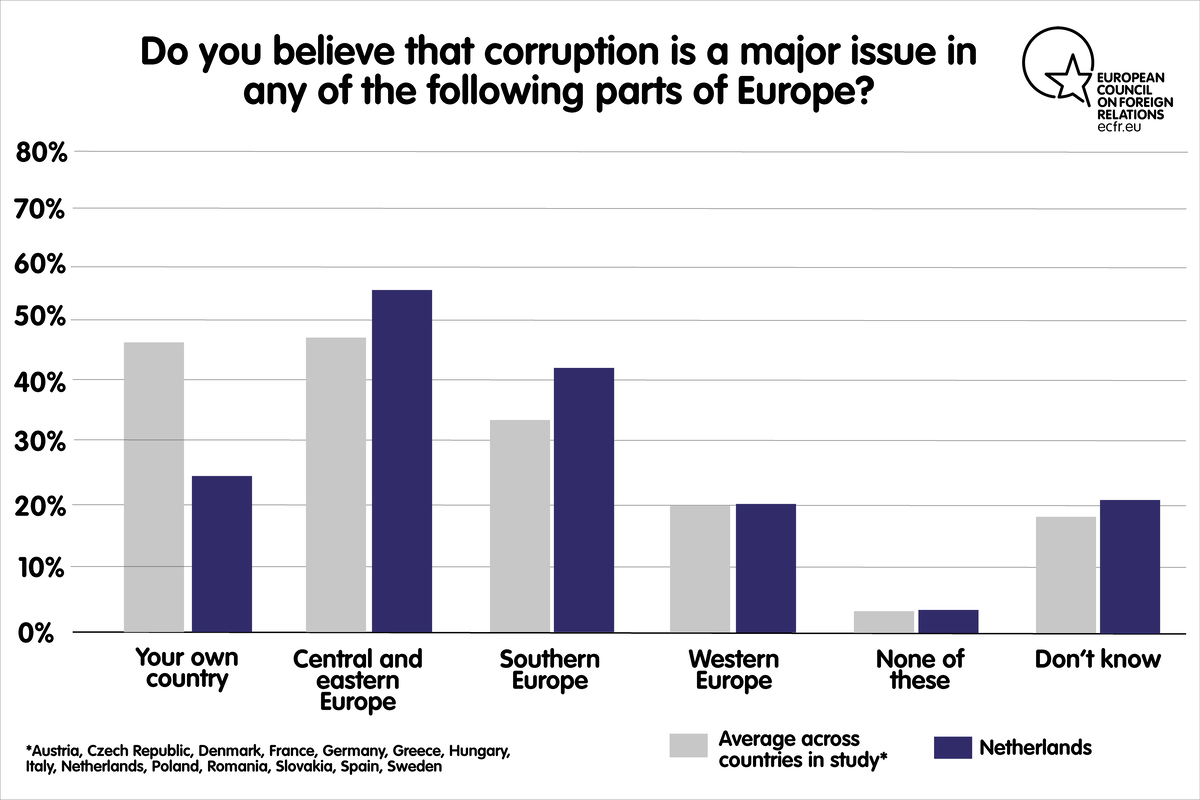

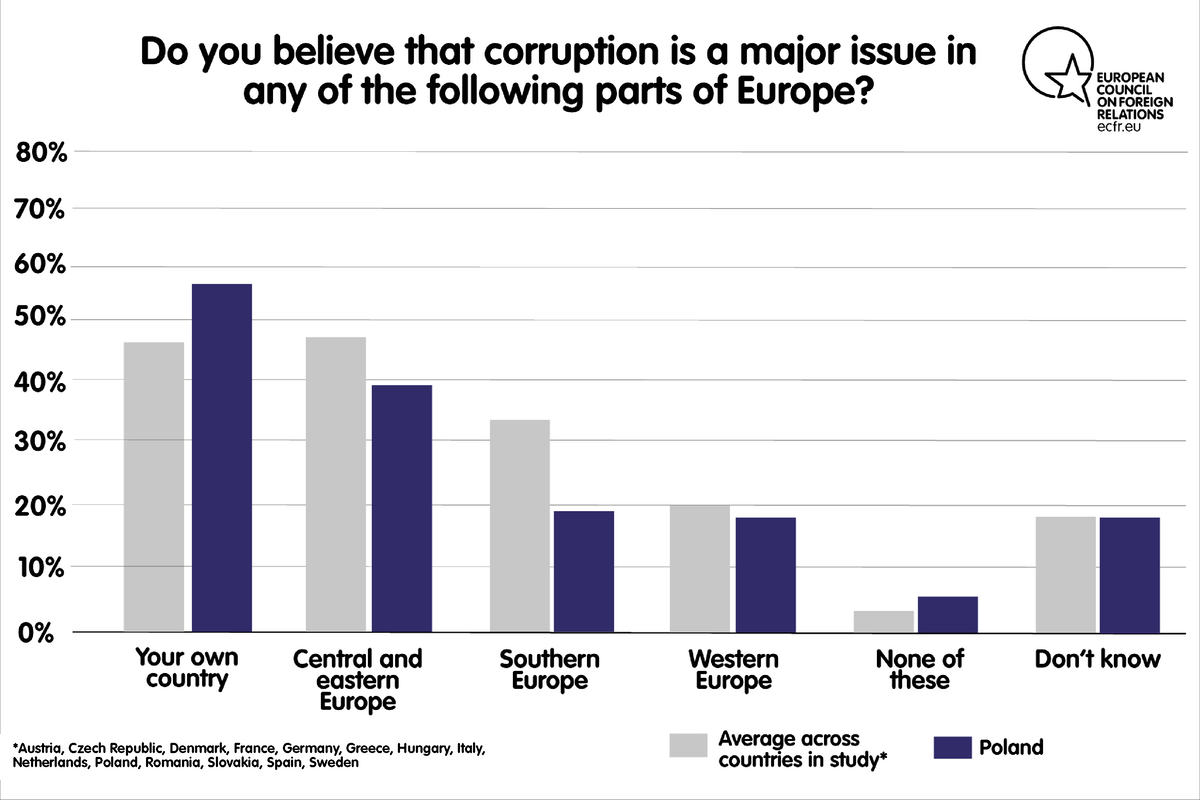

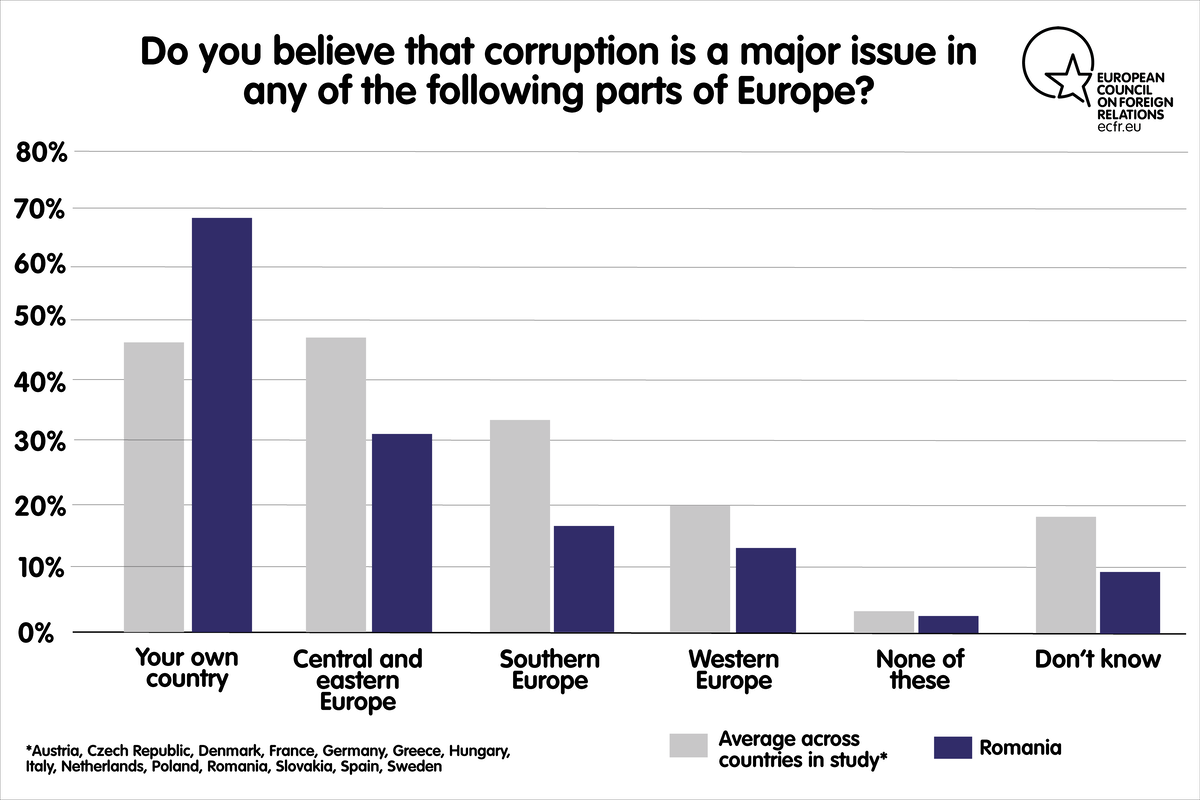

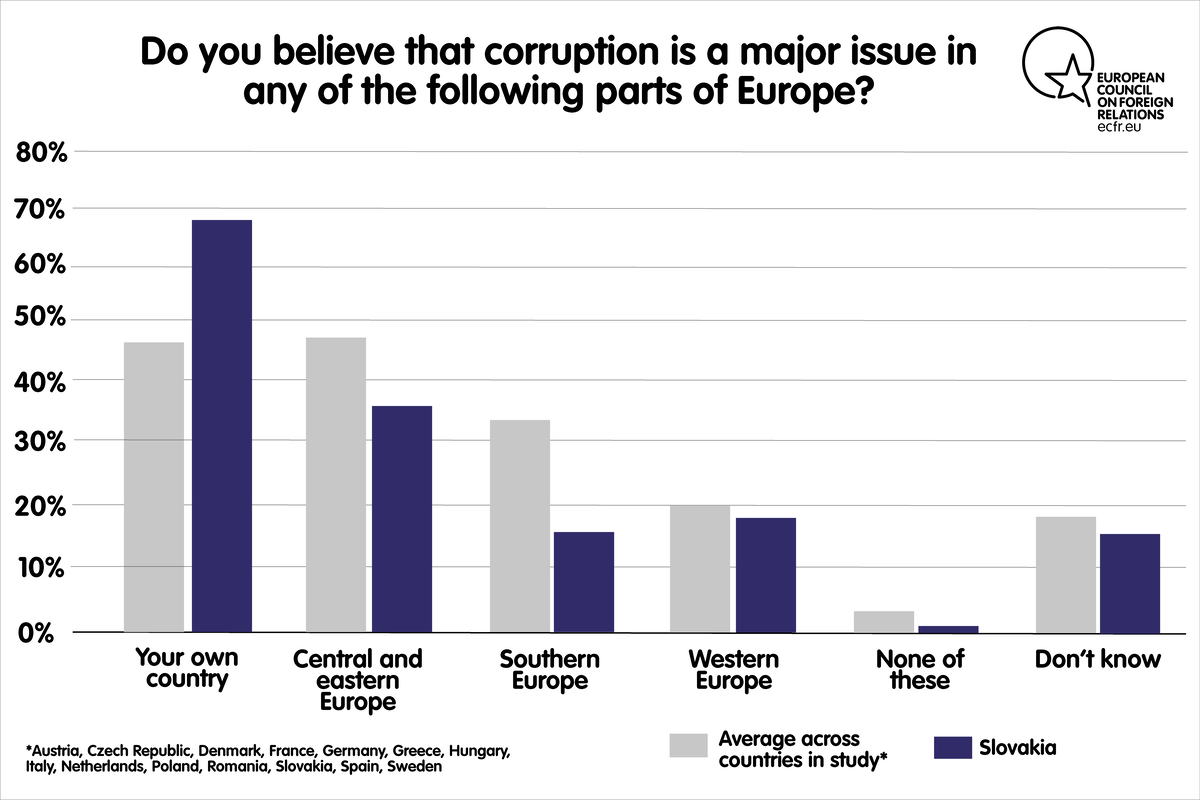

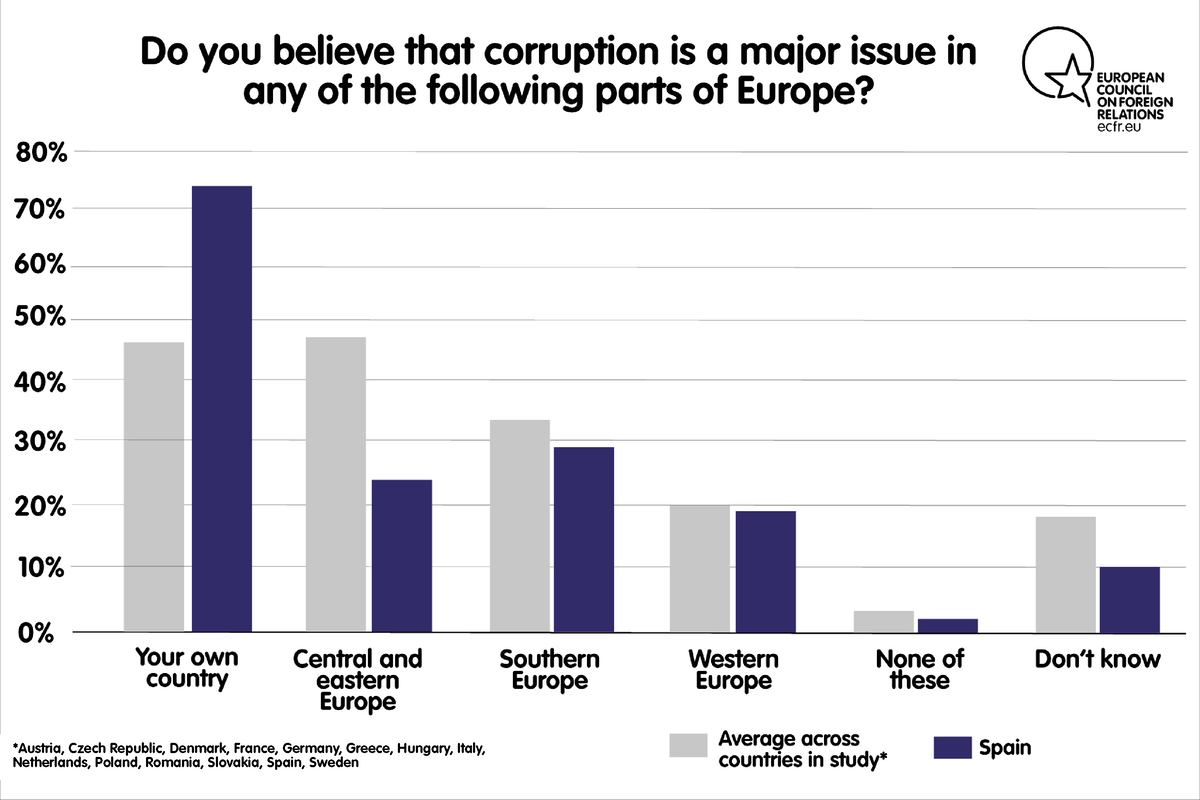

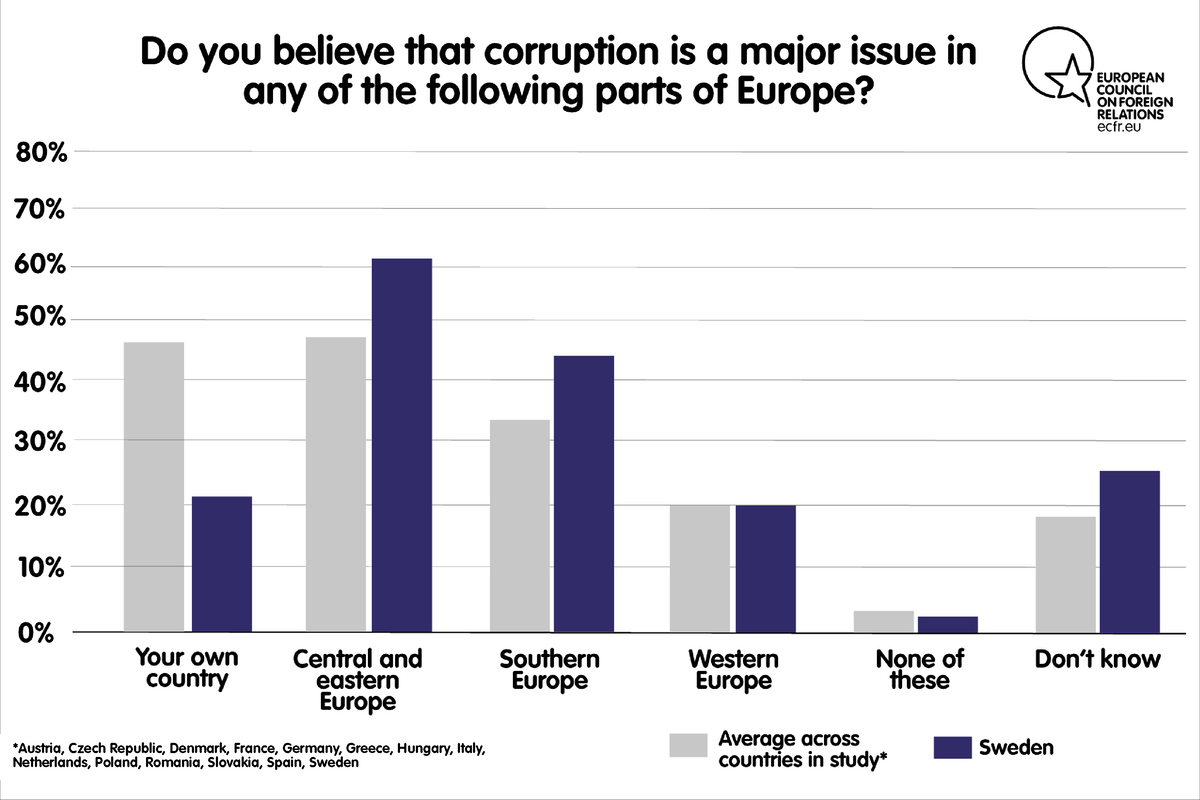

When asked about the biggest threats facing the EU, the response level for “migration” was above the EU average in Austria, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Italy, Slovakia, and Sweden. It was below average in Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, and Spain. And it was exactly the average, at 14 percent, in Denmark. So, there is no clear pattern indicating a heightened preoccupation with migration in eastern Europe. That said, citizens in central and eastern Europe are far more concerned about corruption in their country than they are about migration. The differences in Poland and Slovakia were particularly stark: 19 percent of Poles name corruption, and just 7 percent migration, as a top threat. In Slovakia, 37 percent cite corruption as their greatest worry and just 2 percent opt for migration.

The data show that the west is not homogeneous either. There is a fairly significant divide between southern and northern member states in their concerns about the world. The question of whether states are more concerned about immigration or emigration clearly shows this.

There are many more states that are preoccupied with emigration in the south of the EU than other regions, while those in the north are more concerned about immigration than most others. Respondents in Spain, Italy, and Greece all expressed stronger concerns about fellow nationals leaving their country than they did about new arrivals; this was most pronounced in Greece, at 28 percent to 7 percent. Meanwhile, the opposite is true in Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands (the starkest difference was in the Netherlands, with 6 percent concerned about emigration and 55 percent about immigration). In general, countries in the south and east of the EU fear both immigration and emigration; countries in the north and the west tend to fear neither.

Myth 5: All European elections are exclusively national

The truth: This could be the first truly transnational European Parliament election

Despite their name, European elections have long carried the tag of “second-order national elections”. In other words, they are low-turnout elections that voters use to deliver a message to national politicians.

While there are lots of national dynamics at play – and no Spitzenkandidat has achieved recognition across Europe – the upcoming election promises to have a greater transnational, even pan-European, element than any of its predecessors. This is partly because Bannon is helping Orban and Salvini in his quest to unite the extreme left and the extreme right behind populist leaders, and to provide a European answer to the Trumpian revolution that has disrupted politics across the Atlantic. Orban and Salvini are striving to build a pan-European populist alliance that marries anti-austerity and anti-migration stances, aiming to provide a powerful alternative to more mainstream forces. They seek to capture the institutions in Brussels so that they can reverse European integration from the inside. In their grand visions, they would refound Europe on the basis of illiberal values.

The threat of this movement could also lead to a counter-mobilisation of pro-European voters concerned about the survival of the EU.

When asked what the biggest loss would be if the EU ceased to exist, in most countries concern centres on issues relating to the single market – the freedom to live in, work in, and travel to other countries, and to trade across borders – as well as to the single currency. As noted above, voters in countries such as Hungary, Poland, and Romania see the EU’s role in protecting democracy, the rule of law, and human rights as vital. But there is also a great power dimension to their concerns: voters in France, Germany, Austria, Spain, Denmark, and Italy value the EU’s ability to counter the US and China. Finally, citizens of the three Scandinavian EU members, together with the Netherlands and Austria, appreciate the EU’s role in tackling climate change.

This issue has the potential to be important in mobilising pro-European voters. The data suggest that people who worry about climate change tend to have more optimistic views of the EU, perhaps because they recognise it as an issue that goes beyond the nation state and requires collective action.

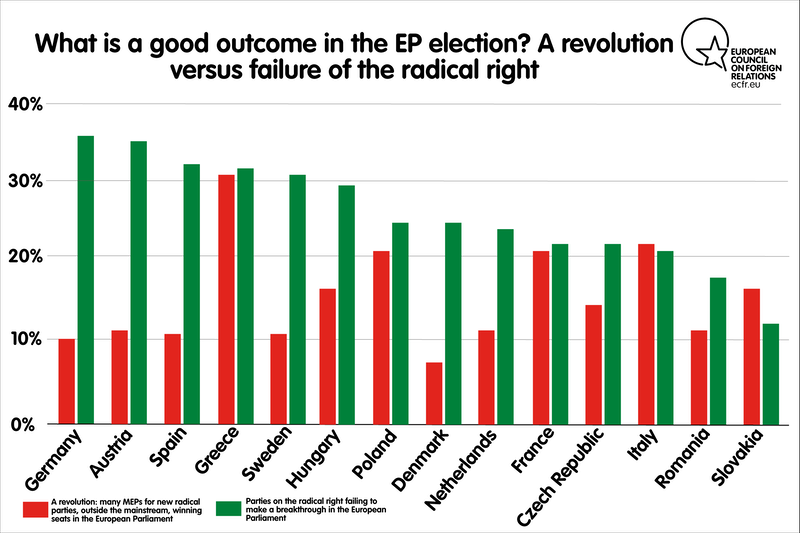

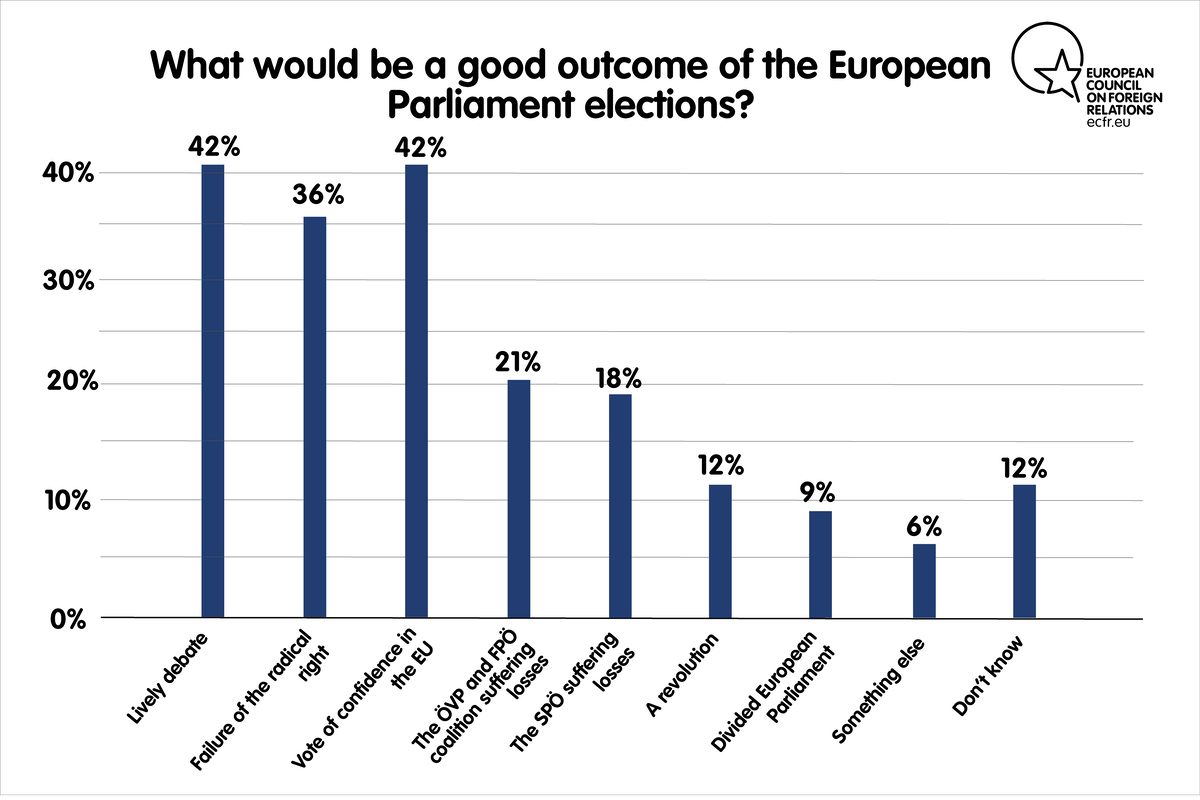

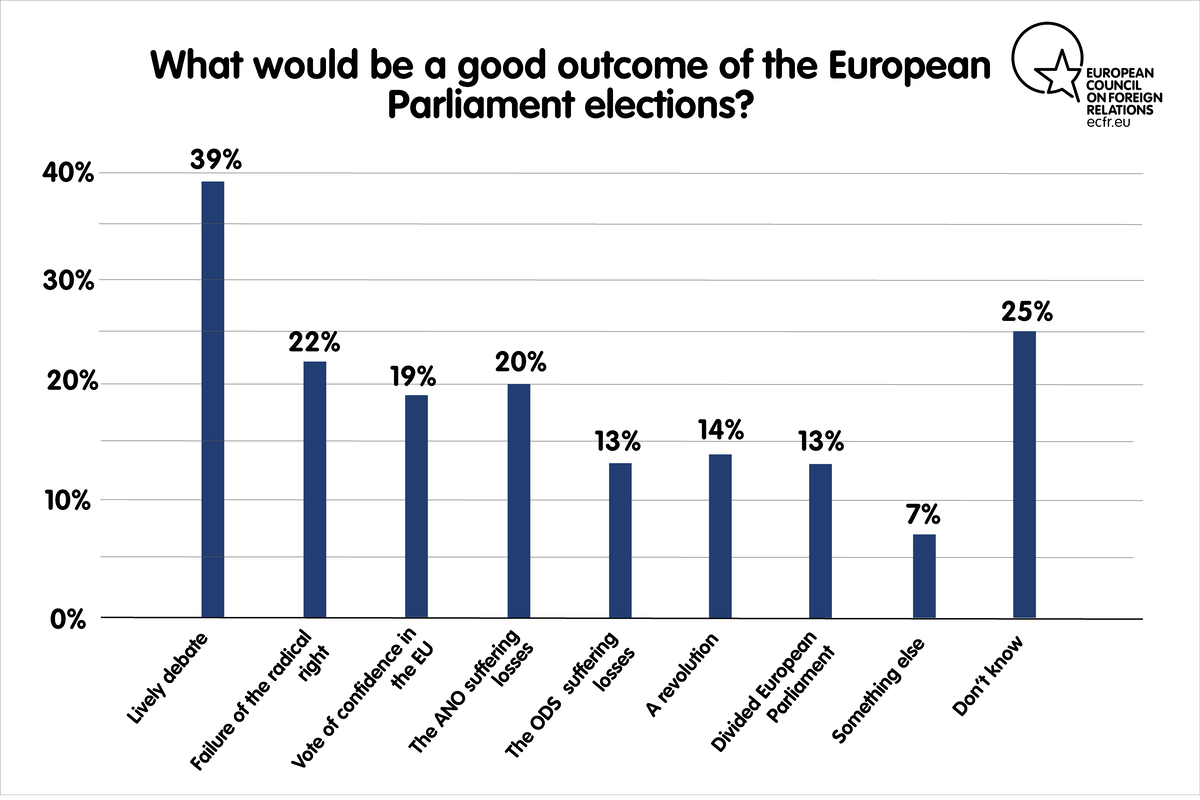

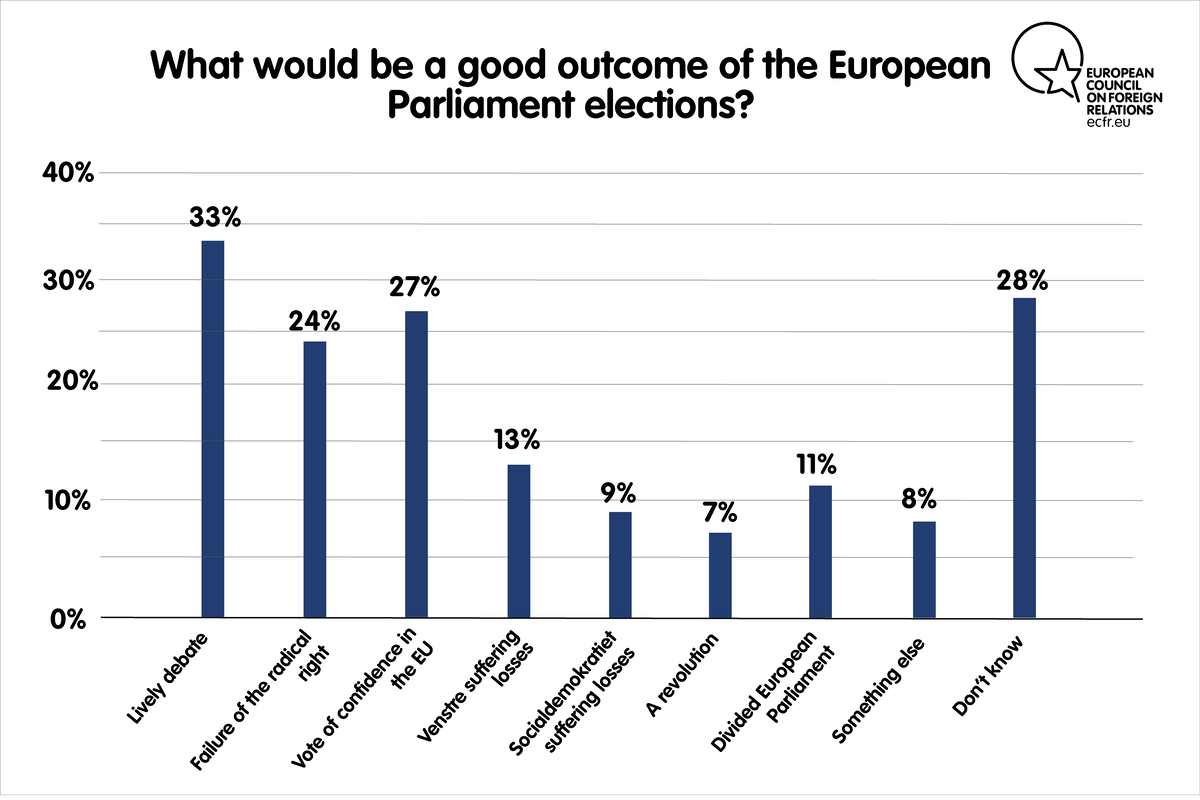

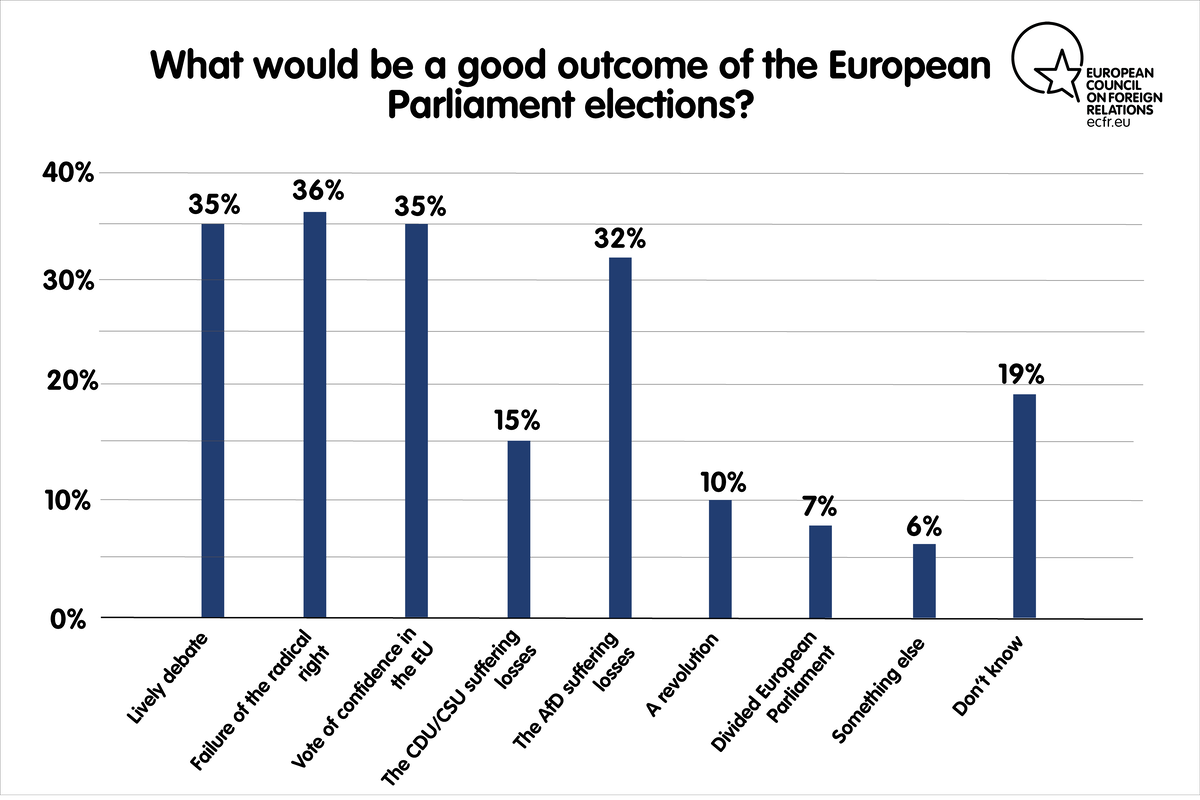

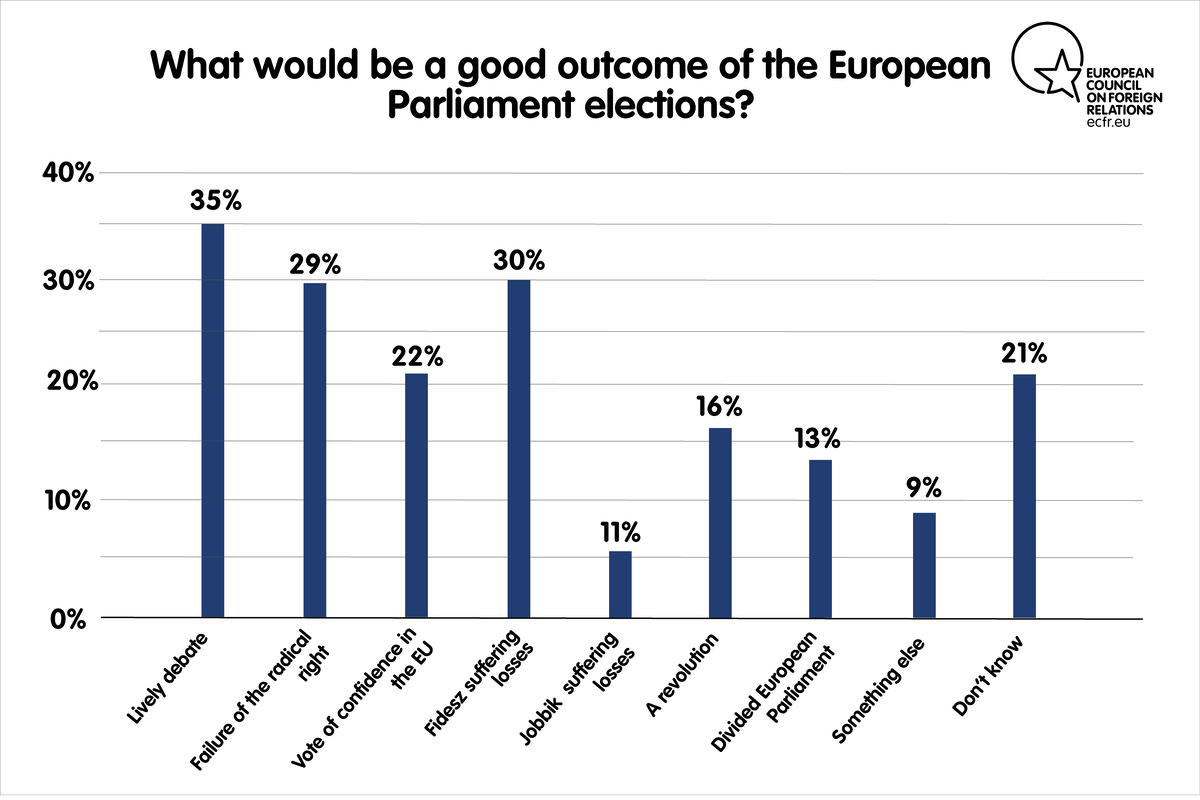

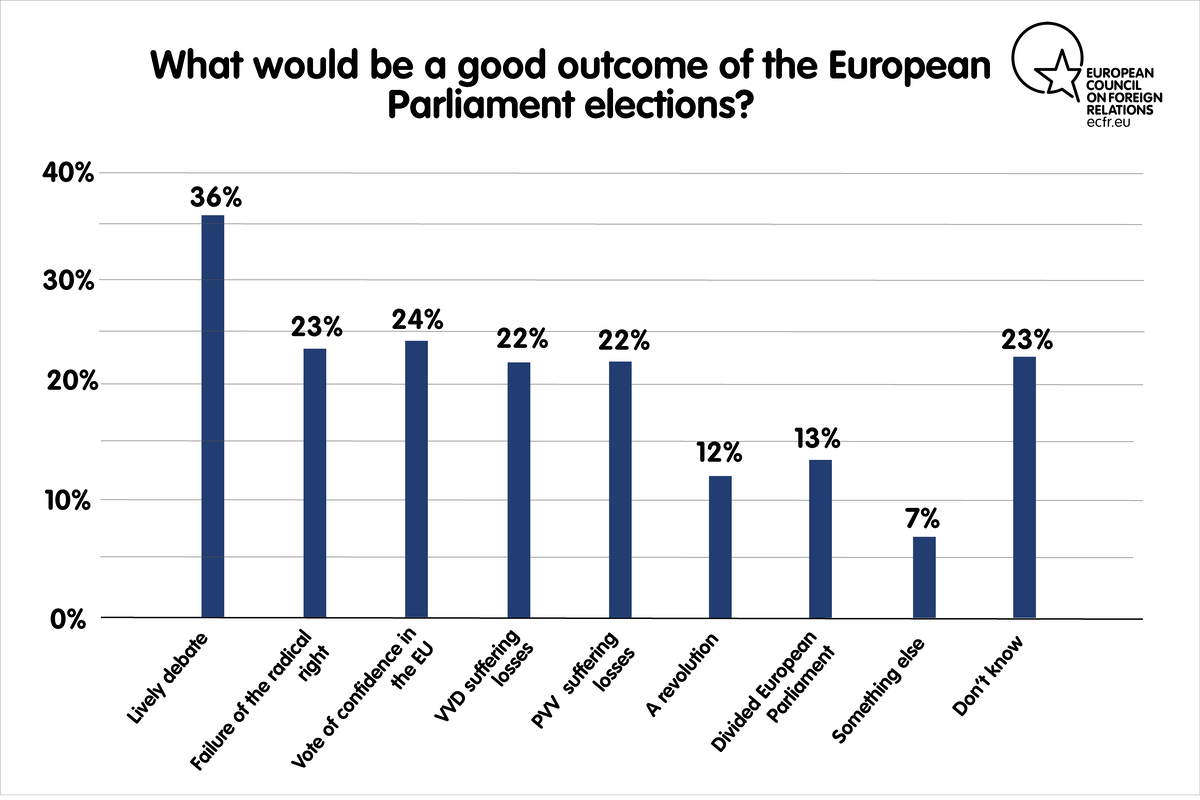

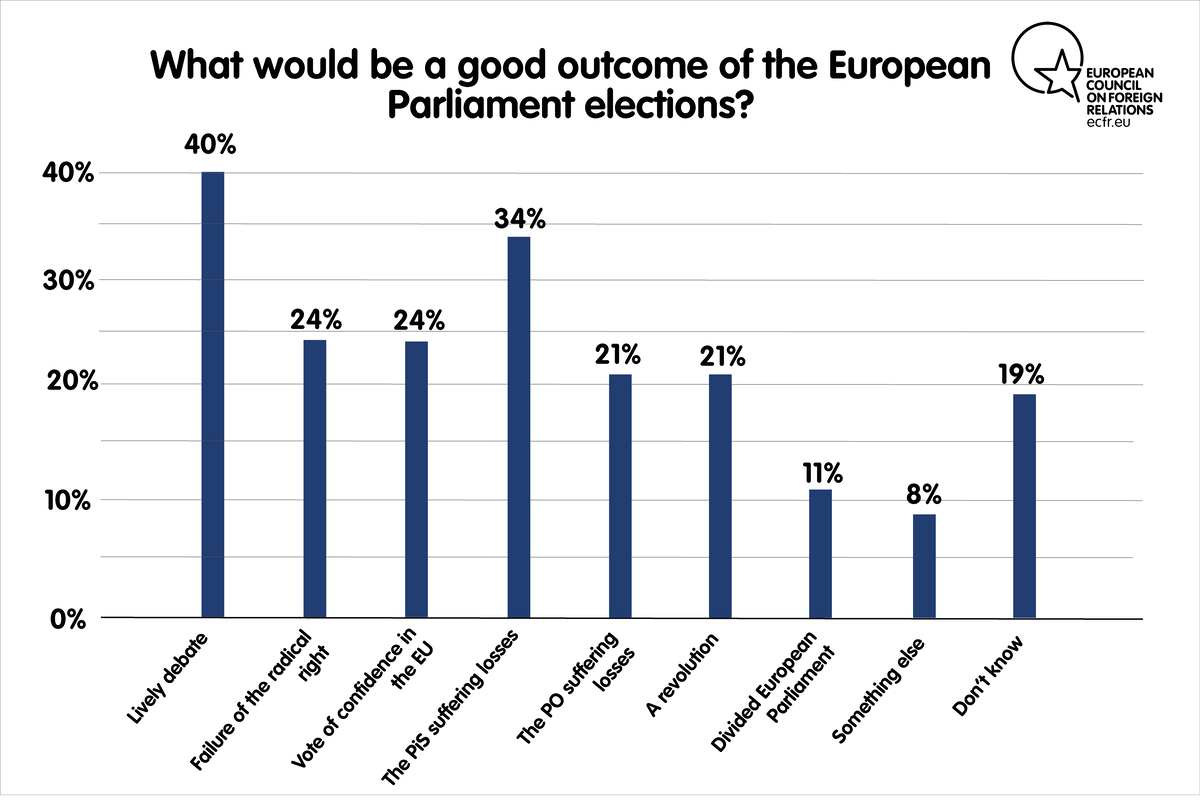

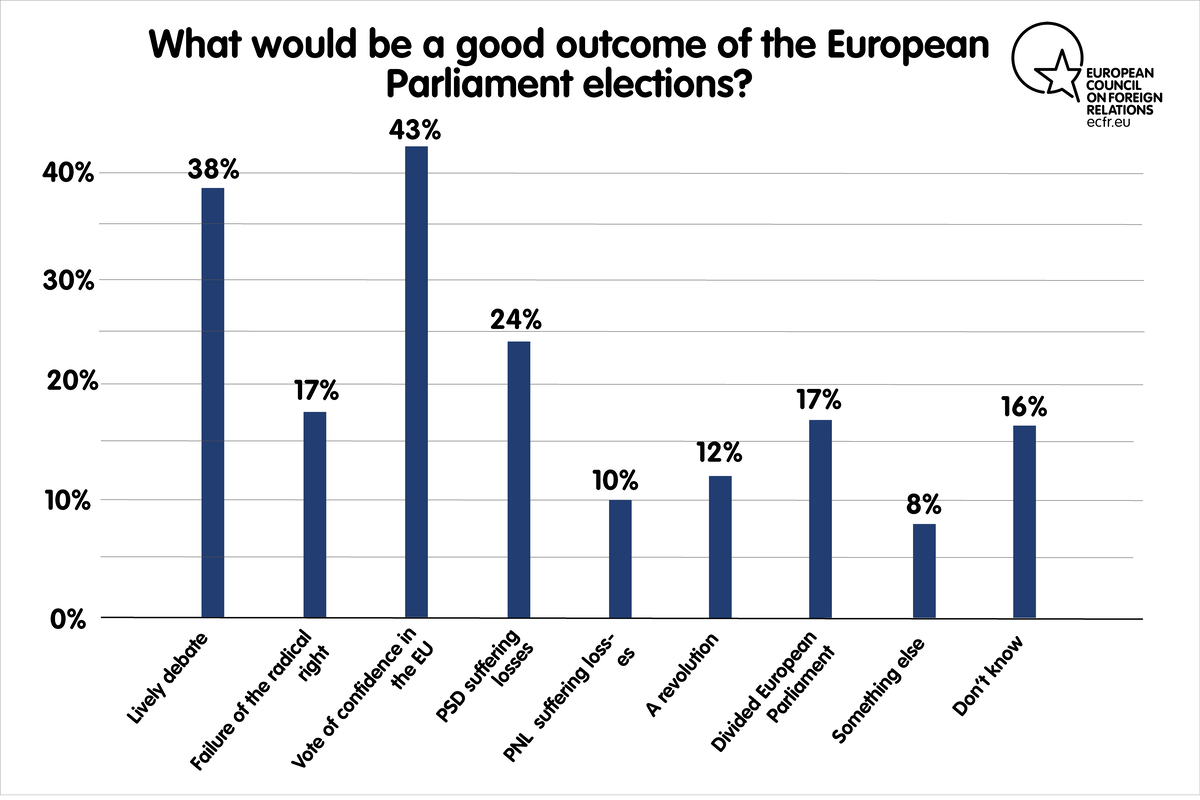

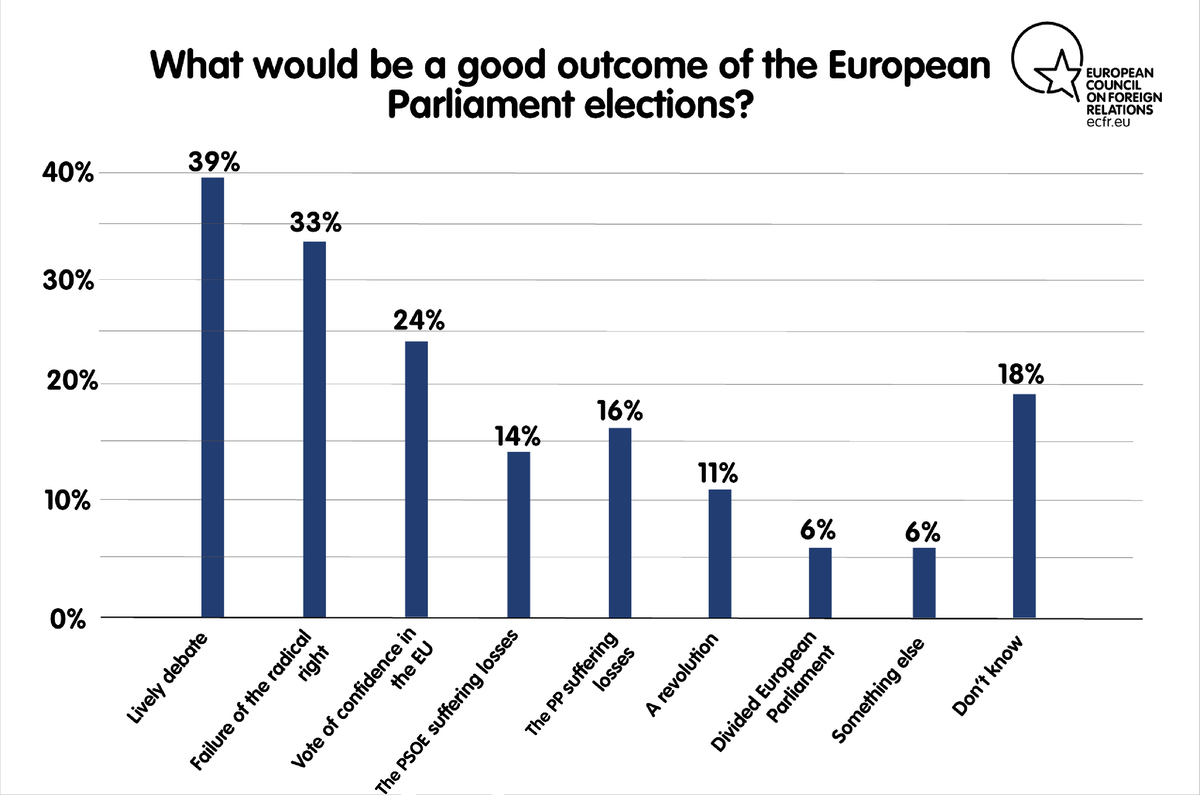

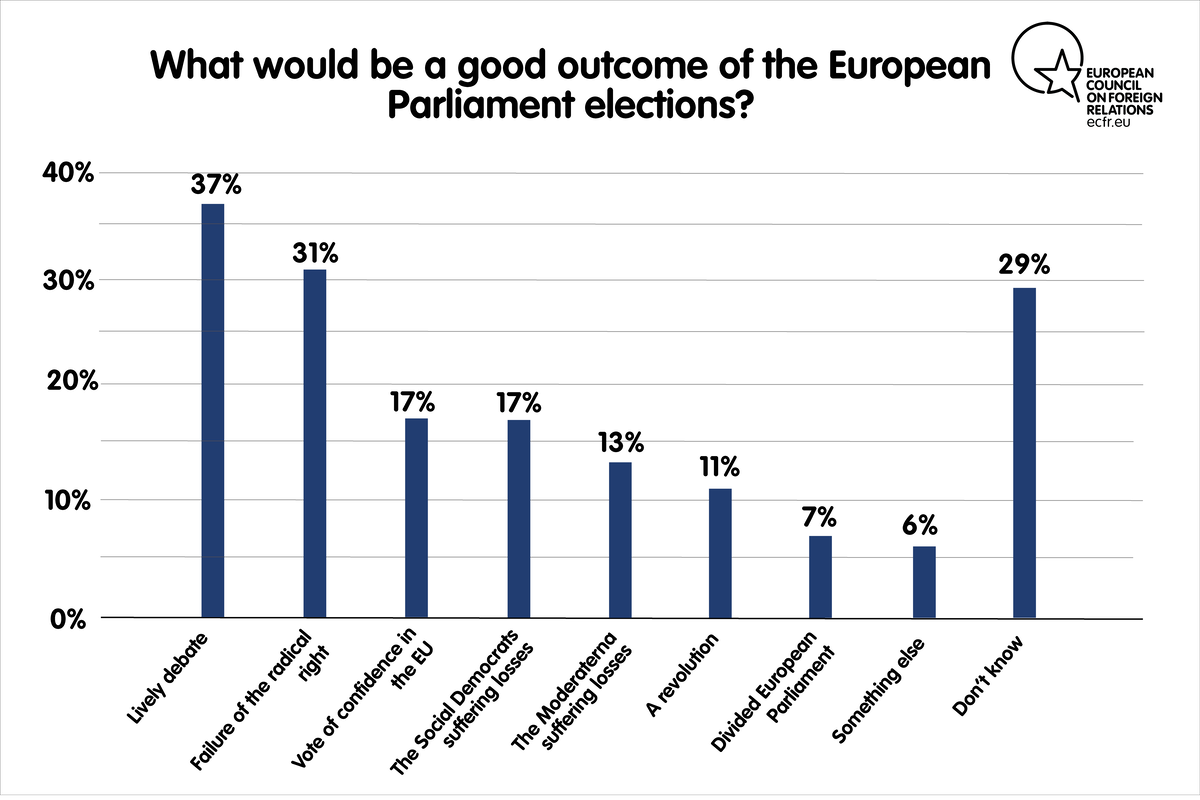

In many member states, there are high levels of concern about the threat of nationalism to the EU’s future among people who are likely to vote. This is partly because the Brexit saga is a key factor in the backdrop to this election – and no other member state wants to follow the UK into this self-imposed chaos. Moreover, even people who have come to terms with nationalist parties in their countries are still worried about Euroscepticism in other states. What has changed since the last European Parliament election, in 2014, is that voters no longer take the EU for granted. Indeed, more people than ever are following the course of the European Parliament election in other EU member states. And stopping the far right is the second most popular definition of a “good election” among respondents to our survey – after the vanilla option of a “lively debate”.

The outcome will be a new kind of ‘hybrid election’ – nationally grounded, but affected by debates elsewhere in Europe. This potential contagion adds to the unpredictability of the May 2019 vote: more than ever, an event in one EU member state could affect the election result in another.

Conclusion: Recapturing the future

For pro-Europeans to win this election, they need to understand two things. Firstly, how to maximise the turnout of voters who are System Believers or members of the Pro-European Left Behind. And, secondly, how to bring some Gilets Jaunes and Nationalist Eurosceptics back into the system.

In all elections nowadays, political parties focus more on persuading their current supporters to vote than on trying to change people’s minds. For this reason, many political parties will focus on the 149 million of people in the EU who are not tempted by anti-European parties but are not sure whether they will bother voting in a European election (this includes undecided voters). In appealing to these people, the biggest challenge is showing that the stakes are high enough to justify turning out to vote.

In addition, party strategists have to realise that, for them, the moment of catholic marriage is over – and many of their voters have endorsed the concept of open marriage. Dyed-in-the-wool party voters are a thing of the past, and today’s European voters – who have a strong concern about corruption – place more emphasis on the integrity of political leaders.

Most voters want change, but do not see that change coming just from the far left or the far right. In France, those who intend to vote for Macron are among those most convinced that the EU is broken. If they want to succeed at the election, pro-European parties must present themselves as parties of reform, standing against the status quo and at the ready to make the changes necessary for a better and more secure future for Europe.

But there is a danger that, if European politics continue like this, with parties only focused only on their existing voters, it will become what the late British political consultant Philip Gould called an empty stadium – where the mainstream parties continue to battle it out as if nothing has changed, but the voters have left. ECFR’s and YouGov’s findings show that the crisis has become so deep that, in many places, political parties need to recover their ‘licence to operate’. Understanding this is central to bringing some of the desperate revolutionaries and nationalist Eurosceptics back into the system.

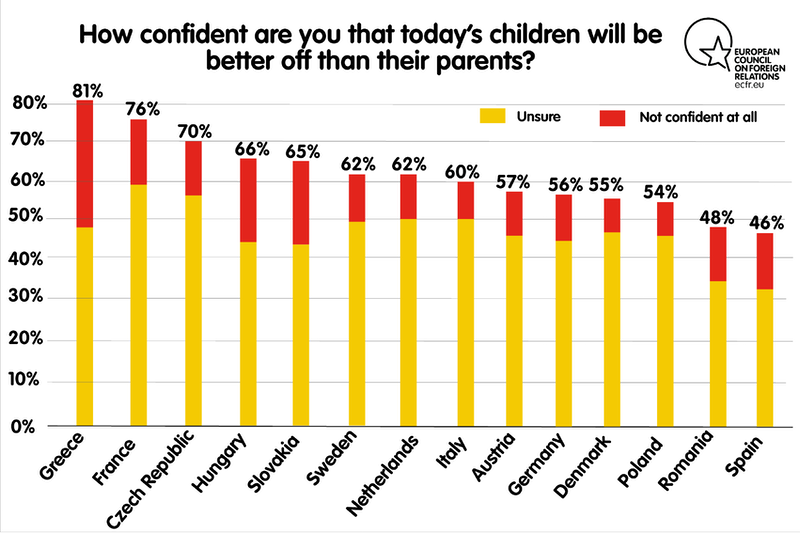

The EU was created by societies that feared their past. Now Europeans fear the future. This is not just about disillusionment with European institutions in Brussels. Many people think that national politics were underpinned by an implicit deal that is now broken.

Their feeling that the deal is broken is most manifest in five areas:

- Economics – If you play by the rules, life gets progressively better – this is no longer true;

- Fairness – People do not believe the government defends people like them, and often believe that the needs of foreigners are prioritised over theirs; they also believe that too many people are able to take advantage of the social welfare system;

- Voice – Citizens no longer believe that you can influence your future through a political system in which you can vote for parties that represent people like them;

- Information – People no longer trust the media and politicians to tell the truth and represent them;

- The political system – Concern about corruption is very high across the EU.

So, particularly among the Gilets Jaunes and Nationalist Eurosceptics, but also among the Pro-European Left Behind, citizens want to vote for change that will bring them their preferred past. Yet this past differs greatly between political parties. These confused voters have ideas that are contradictory in many ways, and their decision-making is quite driven by emotion. If the problem in the UK and the US is that voters are firmly committed to their tribes, the problem for European parties is that they are ready to move in many different directions. As a result, the way they vote could be shaped by events shortly before the election.

Bringing these voters back into the system does not necessarily call for a new grand vision but will instead require assembling support by proposing changes that resonate with them.

Our data shows that the environment offers one channel for doing this – turning the fear of the status quo into hope for a common, sustainable future. The economy is another option – as seen in EU efforts to take tough action on digital companies that are exploiting our future.

Pushing back against superpowers such as China and the US could offer a further channel in a Europe that is fearful about threats from such states.

To win a hearing, pro-European parties will also need to take some defensive action. Instead of selling only a European project that exists to rip down borders between people and countries, the EU needs to make interdependence safe again. That means giving real meaning to the rhetoric of “a Europe that protects”. The French philosopher Régis Debray has argued that a well-protected border is “a vaccine against the epidemic of walls”. And, in today’s Europe, where so many settled boundaries seem to be melting, there is a clear craving for borders and control. Many people have seen the certainties that defined their lives collapsing: the barriers between the developed and developing worlds, social structures, and moral codes – even the difference between men and women. However, misinterpreting this desire for boundaries as a simple call to fight an election on immigration will lead to pro-Europeans failing voters once more. They need to regain their licence to operate, setting out a future for the European project that resonates with citizens – one that they are capable of delivering.

1 The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America is Tearing us Apart, Bill Bishop, Mariner Books, 2004.

2 Poland, where the electorate is distinctly polarised, is the exception to this.

3 See, for example, Piège d’identité, by Gilles Finchelstein, Fayard, 2016.

Methodology

This report is based on a large sample-size pan-European poll carried out by YouGov for ECFR between 23 January and 25 February 2019. The questions covered the issues that are driving voters’ thinking about the European Union, and their decisions on how to vote in the European Parliament elections.

The countries covered were Austria (2000), Czech Republic (1000), Denmark (2,500), France (5000), Germany(5000), Greece (500), Hungary (4000), Italy (5000), the Netherlands (2000), Poland (5000), Romania (1000), Slovakia (500), Spain (5000), and Sweden (4000). This is a total of 46,000 polled.

In follow up, we carried out focus groups in Germany, France, Italy and Poland with representatives of the different groups (divided on the basis of their responses to the question of whether or not the national and European systems were broken) exploring their feelings about community, agency, the future and the world around them in March 2019.

Results by country

Austria

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_at_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_at_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Czech Republic

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_cz_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_cz_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Denmark

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_dk_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_dk_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

France

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_fr_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_fr_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Germany

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_de_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_de_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Greece

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_gr_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_gr_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Hungary

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_hu_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_hu_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Italy

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_it_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_it_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Netherlands

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_nl_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_nl_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Poland

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_pl_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_pl_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Romania

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_ro_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_ro_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Slovakia

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_sk_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_sk_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Spain

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_es_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_es_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

Sweden

![What do you think are the two most important issues [COUNTRY] is facing at this moment?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_8_se_What%20do%20you%20think%20are%20the%20two%20most%20important%20%20issues%20Germany%20is%20facing%20at%20this%20moment_.png)

![Are you more worried about people coming into your country or [NATIONALITY] people leaving?](https://ecfr.eu/images/unlock-myths/1200/Country_7_se_%20Are%20you%20more%20worried%20about%20people%20coming%20into%20your%20country%20or%20NATIONALITY%5D%20people%20leaving_.png)

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.