The 2019 European election: How anti-Europeans plan to wreck Europe and what can be done to stop it

Summary

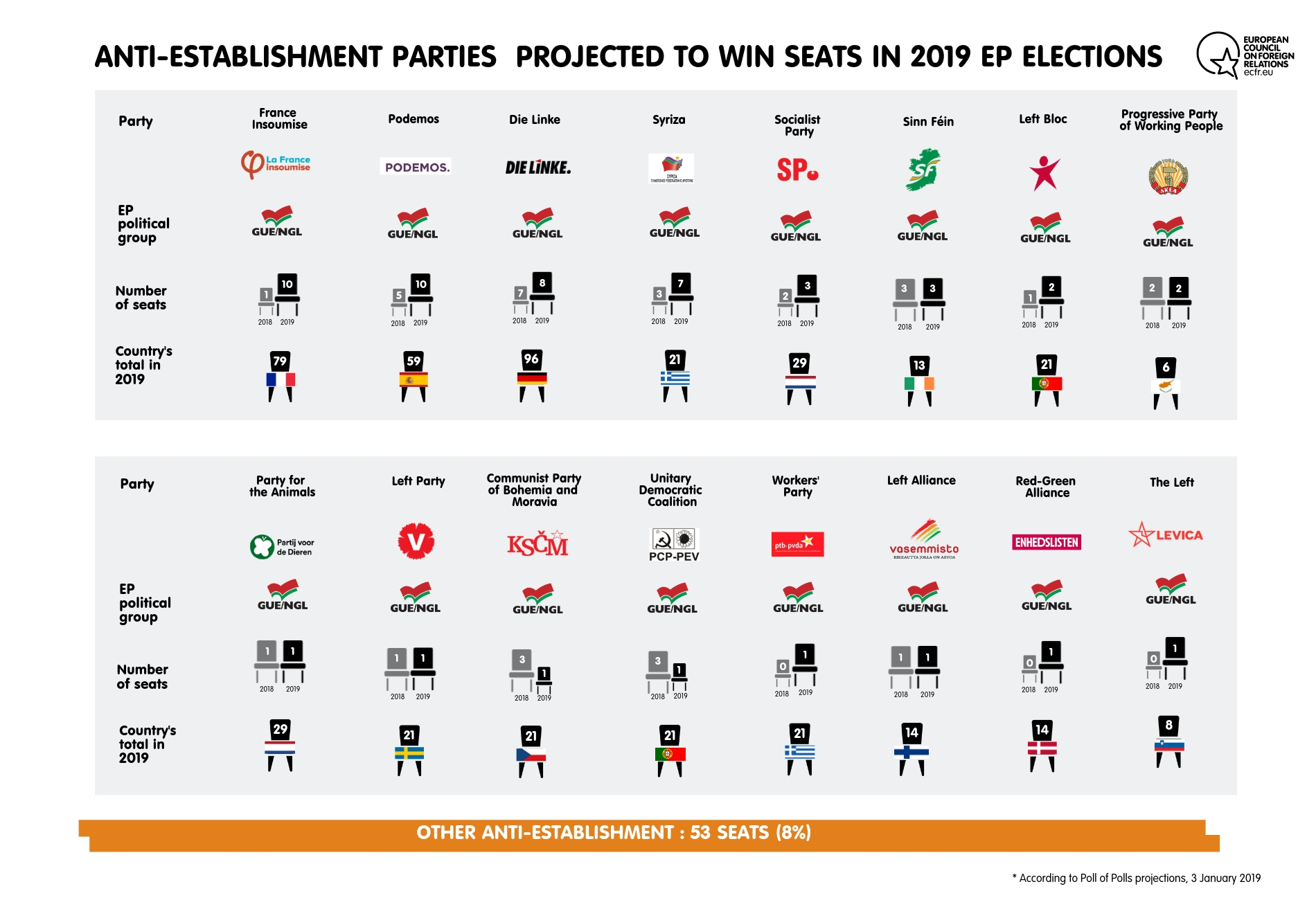

- With anti-Europeans on their way to winning more than one-third of seats in the next European Parliament, the stakes in the May 2019 election are unusually high.

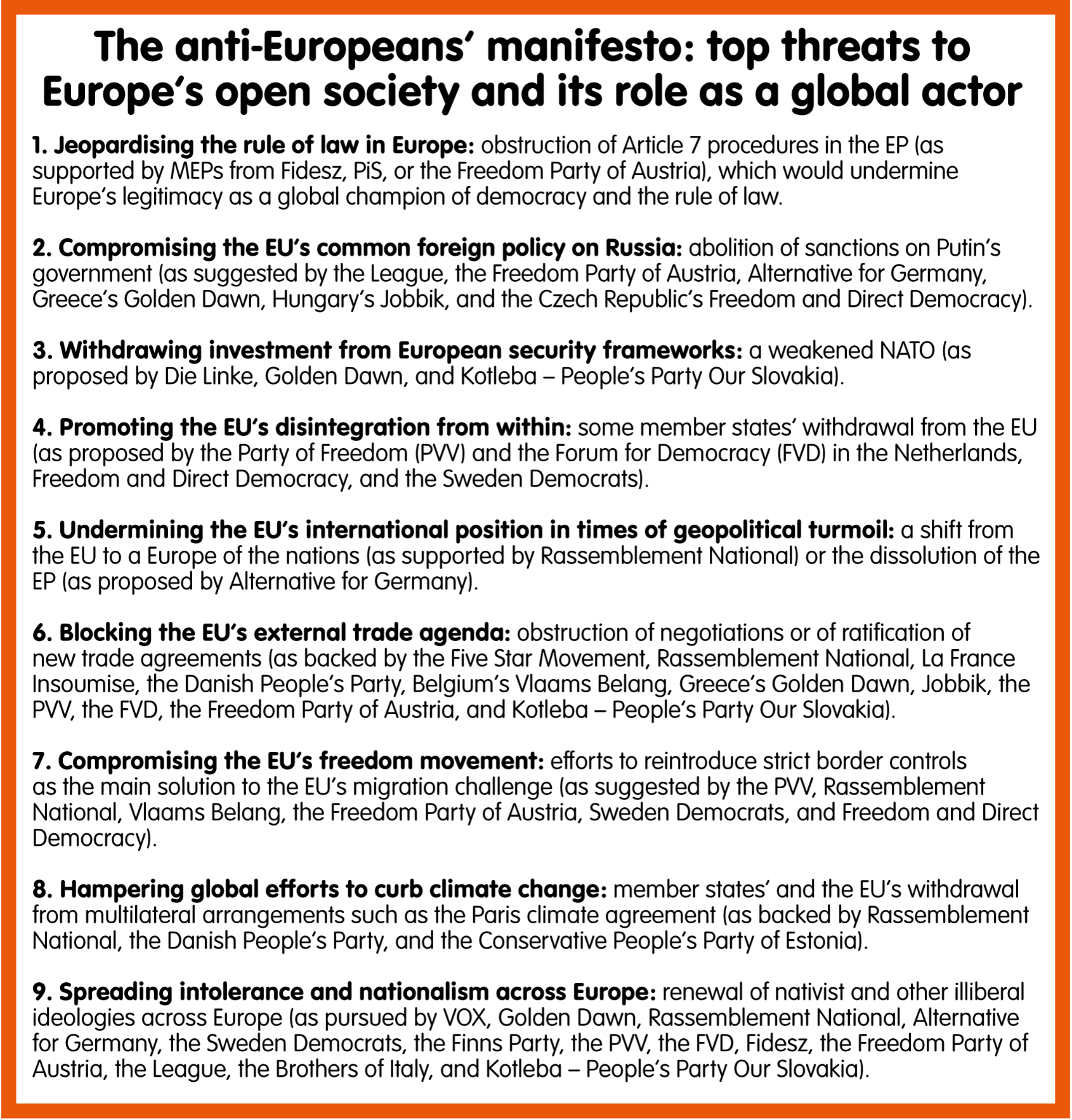

- While there are significant divides between them on substance, anti-European parties could align with one another tactically in support of a range of ideas: from abolishing sanctions on Russia to blocking the EU’s foreign trade agenda, to pulling the drawbridge up against migration. This would put at risk Europe’s capacity to defend its citizens from external threats at exactly the time when, given global turmoil, it needs to show more resolve, cooperation, and global leadership.

- This paper marks the start of ECFR’s campaign to strengthen Europe in the face of efforts by anti-European parties to divide it and make it weaker. We analyse, in detail, the political situation in each of the EU’s 27 member states ahead of the 2019 EP election.

- For supporters of an outward-looking Europe, we offer a strategy to fight back: by driving a wedge between anti-European parties, exposing the real-world costs of their key policy ideas, and identifying new issues that could inspire voters: from the rule of law and the environment to prosperity and Europe’s foreign policy goals.

- In the coming months, ECFR will explore these issues at a more granular level through quantitative and qualitative surveys across the EU27.

Introduction

Europeans have a growing litany of worries. With US President Donald Trump dismantling the fundamentals of the multilateral system and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, conducting a large-scale misinformation campaign designed to undermine European political systems, the European Parliament (EP) election scheduled for May 2019 might seem like a relatively minor concern. The EP is, after all, only one of the European Union’s governing bodies and, in many ways, the least powerful of them. In its legislative role, the institution cooperates with the Council of the EU (comprising national ministers from EU member states) and bases its work on proposals from the European Commission. And, despite having the ability to pass resolutions on a wide range of subjects, the EP has no formal role in foreign policy.

Unfortunately for beleaguered internationalist Europeans, the election really does matter. The vote could see a group of nationalist anti-European political parties that advocate a return to a “Europe of the nations” win a controlling share of seats in the EP. Among them number many figures who are strongly sceptical of free trade, in favour of pulling the drawbridge up against migration, and supportive of Moscow’s arguments about the need to flout international law in the Russian national interest in Ukraine. They are not currently a unified alliance but, in an EP in which their voices entered the mainstream, and in an EU in which transactional decision-making was commonplace, they could let all these ideas shape European policy in the medium term. And, in the longer term, their ability to paralyse decision-making at the centre of the EU would defuse pro-Europeans’ argument that the project is imperfect but capable of reform. At this point, the EU would be living on borrowed time.

Consequently, underestimating the importance of this election could have a very high cost for liberal internationalists across the EU. In the battle for EP seats, turnout will be critical in determining how anti-European forces fare. If nationalist parties marshal the clearest, loudest, arguments, and significant numbers of anti-Europeans turn out to vote, the views of Europe’s silent majority will be drowned out in the new parliament. The experience of the 2016 Brexit referendum shows the mobilising power of a rejection of the status quo in the current political climate. And, regardless of whether anti-European parties increase their share of EP seats, the battle of ideas that they are launching looks set to reshape Europe’s political landscape for years to come. In both contests, pro-European forces have the potential to repel the attack. But, to succeed, they cannot simply defend the status quo or engage in the polarised debate that the other side is currently shaping. In doing so, they risk fatally misunderstanding European popular sentiment and becoming an easy opponent for those who seek to undermine the project.

To understand the implications of the vote, ECFR conducted a study in the 27 member states that will go to the polls in May 2019. Our network of associate researchers in EU capitals interviewed political parties, policymakers, and policy experts, while analysing opinion polls, patterns in voter segmentation, and party manifestos. Even though Europe is still in the early stages of preparing for the election, it is already clear that this will be the most consequential parliamentary vote in the EU’s history.

ECFR has, therefore, set up the Unlock Europe’s Majority project to push back against the rise of anti-Europeanism that weakens Europe and its influence in the world, and to show how different parties and movements can – rather than competing in the nationalist or populist debate – effectively rally, knit together, and give the pro-European, internationally engaged majority in Europe a new voice. Over the coming weeks and months, ECFR will develop in-depth analysis informed by polling and focus group data about the various tribes and shifting coalitions in Europe that favour a more internationally engaged EU, as well as lay out what would be at stake with an EU in decline. ECFR will use this research to engage with pro-European parties, civil society allies, and media outlets on how to frame nationally relevant issues in a way that will reach across constituencies and reach the ears of voters who oppose an inward-looking, nationalist, and illiberal version of Europe.

No ordinary EP election

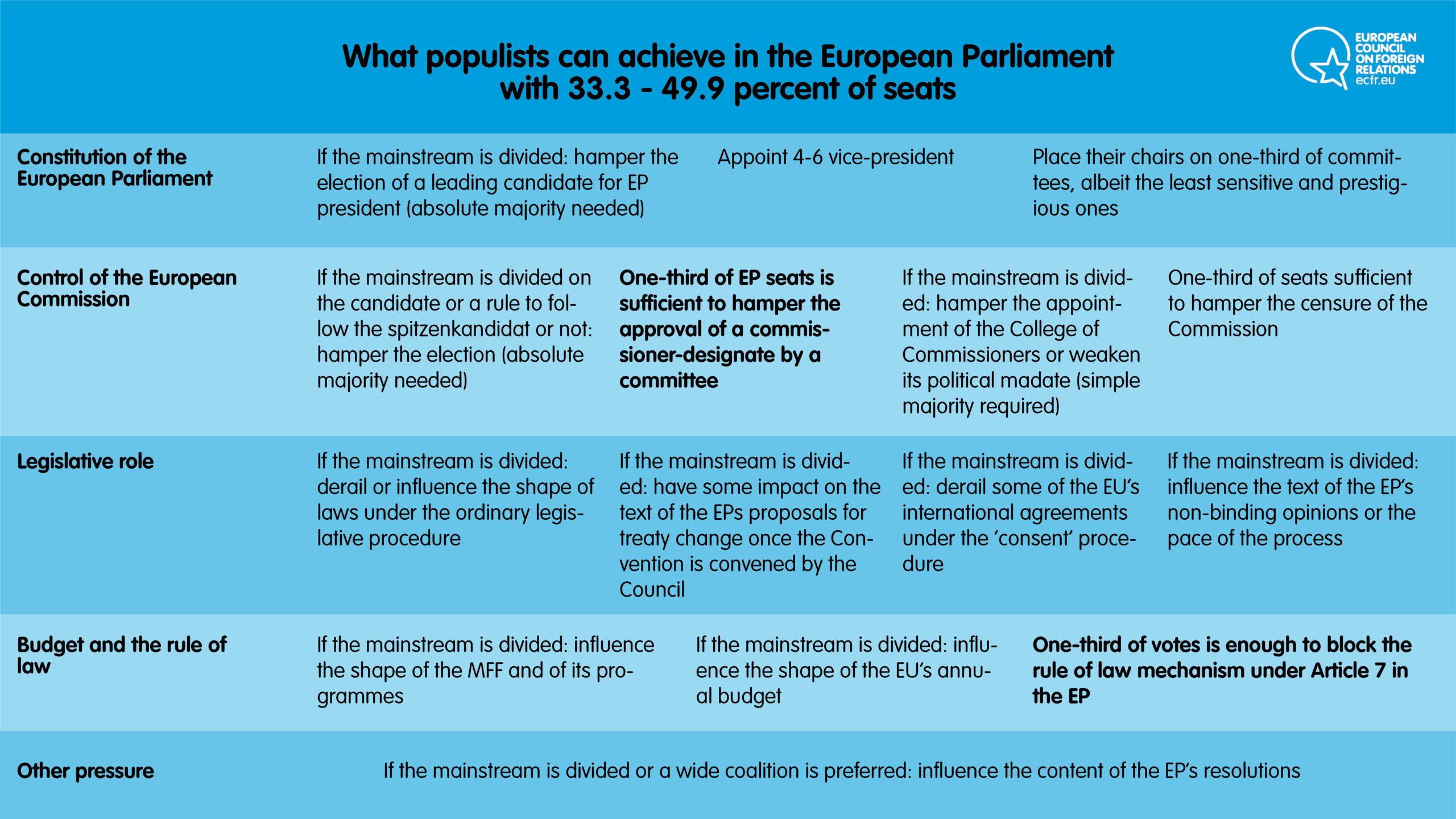

The first challenge pro-Europeans must understand if they are to succeed in the EP election is a mathematical one. Simply put, winning a certain number of seats will give anti-European forces influence over key processes and decisions. Judging by what many of them have campaigned for, anti-European parties could use this increased share of seats to obstruct the EP’s work on foreign policy, eurozone reform, and freedom of movement, and could limit the EU’s capacity to preserve European values relating to liberty of expression, the rule of law, and civil rights.

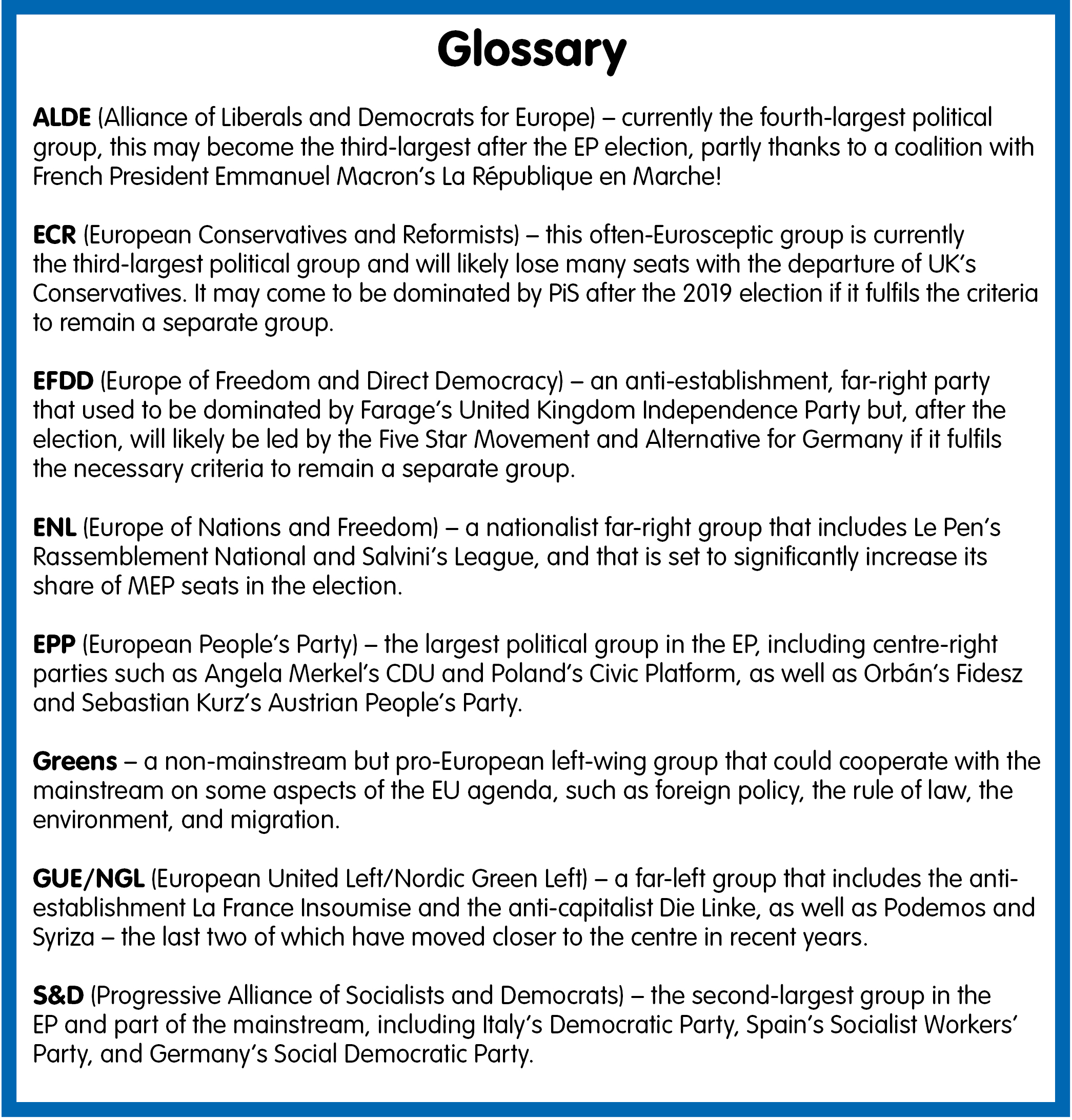

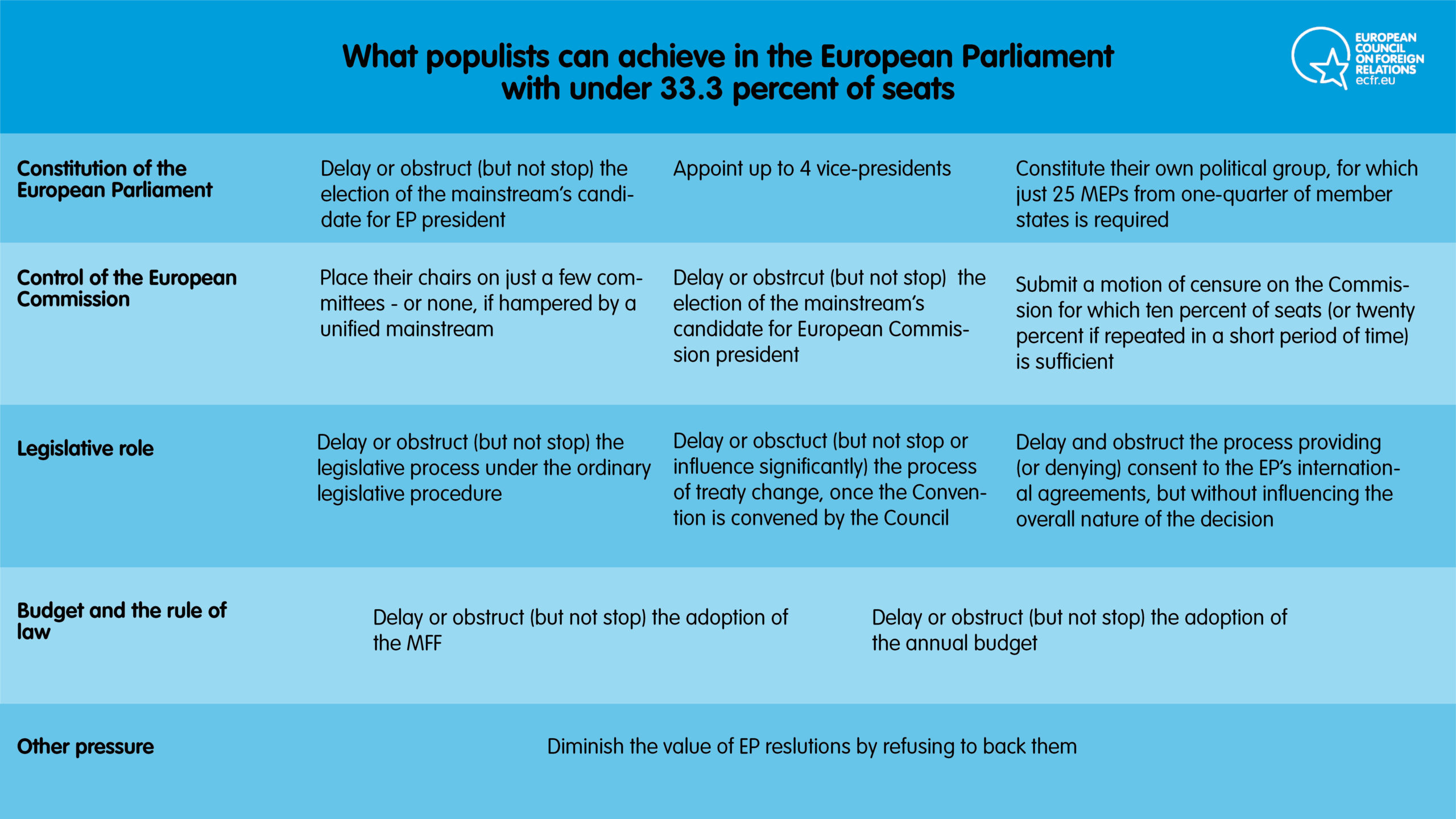

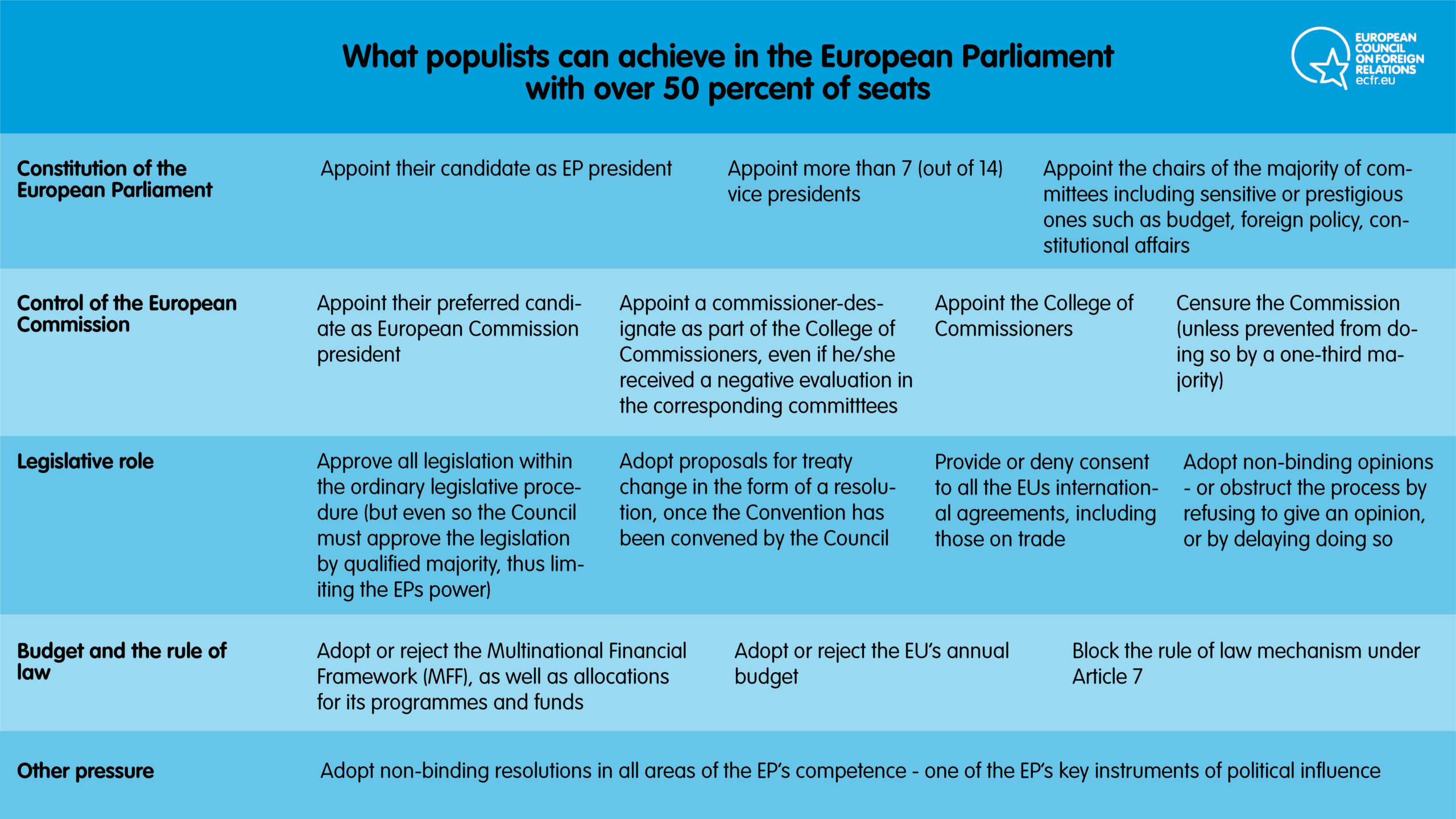

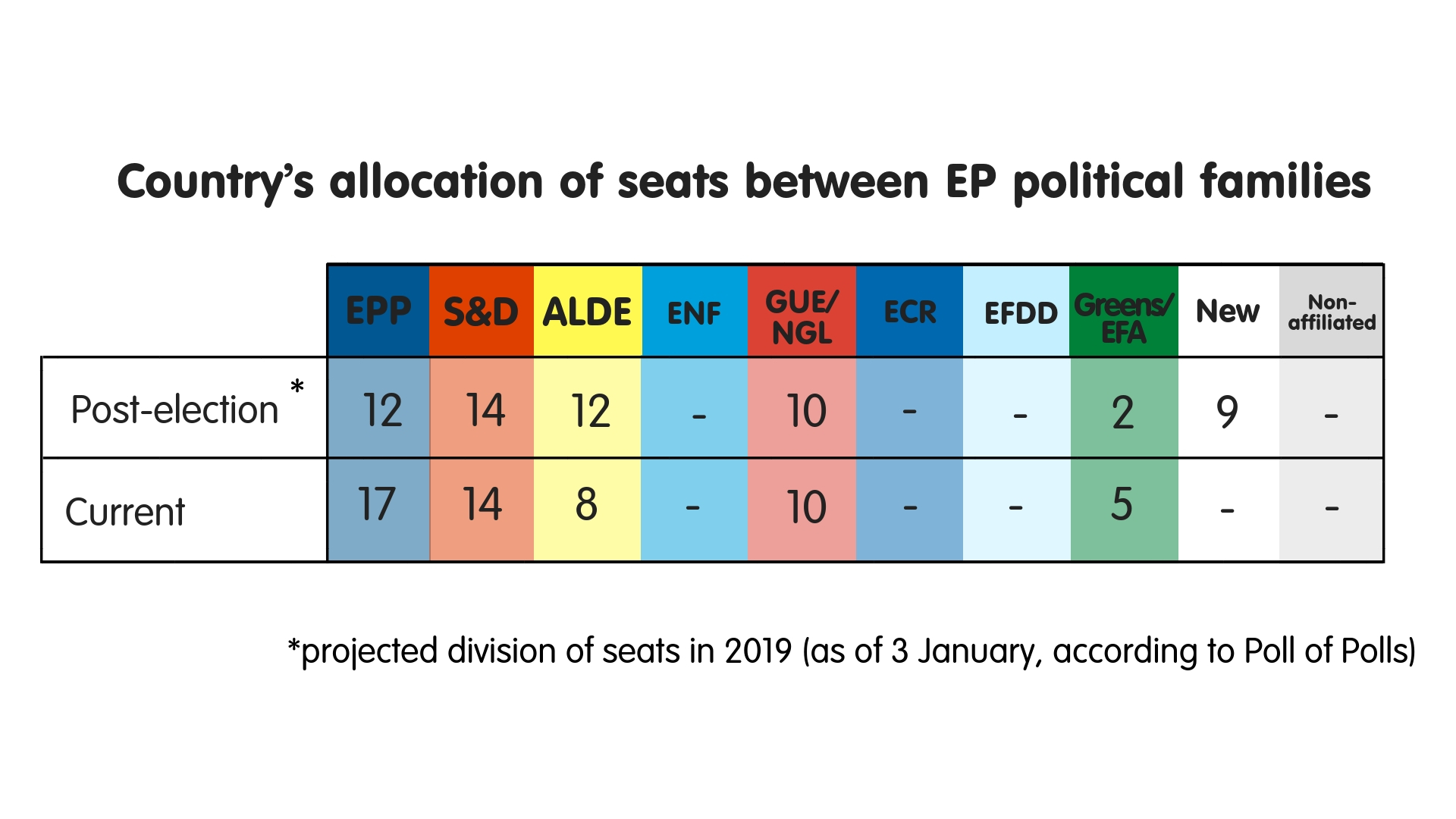

Winning more than 33 percent of seats would enable them to form a minority that could block some of the EU’s procedures and make the adoption of new legislation much more cumbersome – with a potentially damaging impact on the content of the EU’s foreign policy, as well as on the EU’s overall institutional readiness and its political credibility to take initiatives in the area. The table above outlines the possible procedural consequences of crossing this threshold.[1] Below, we explore in more detail the challenges for the EU’s foreign policy writ large.

Foreign trade

When the leader of Italy’s Five Star Movement, Luigi di Maio, criticises the EU’s external trade agenda – saying, “if so much as one Italian official continues to defend treaties like CETA, they will be removed” – he expresses a view shared by several of Europe’s anti-European parties on both the far left (La France Insoumise) and the far right (Rassemblement National). In the next parliament, trade could become a consensus issue on which they display an image of unity, challenge the mainstream’s capacity to seek wider compromises, and influence the EU’s policies.

The role of the EP in international trade agreements has continuously grown in recent years. The Lisbon Treaty gives the EP veto power over almost all trade and other international agreements, due to the consent procedure – which requires an absolute majority. (The procedure is also used for the accession of new EU member states and arrangements for withdrawal from the EU, as seen in the EP’s role in the Brexit process.) Thus, the EP can provide or deny consent for the conclusion of an agreement prior to authorisation by the Council of the EU.

The EP was quick to use its new powers, rejecting in February 2010 the initial version of the SWIFT agreement. It has also exercised a strong influence elsewhere – notably, in negotiations on free trade agreements with South Korea, Canada, and the United States (it is expected to play a vital role in a future trade agreement between the EU and the United Kingdom). The EU’s agreement with Singapore led to temporary uncertainty on the scope of the union’s exclusive competence on trade. Following the European Court of Justice’s Opinion 2/15, which distinguished between EU-only and mixed agreements, there is a widespread expectation that most of the EU’s upcoming trade agreements will now include only those elements that are within the EU’s exclusive competence, to avoid a lengthy ratification process in member states.

The threat of a parliamentary veto is enough to shape the EU’s trade policies. Therefore, controlling the majority of EP seats is crucial, as it can otherwise be difficult to gain the EP’s consent. According to VoteWatch, the balance of power on trade-related decisions is unlikely to change much in the next EP, mostly because several anti-European parties either do not oppose free trade outright (Alternative for Germany) or are among its most stable supporters (Law and Justice, or PiS). But, given the risk that they could seek tactical alliances, and the fact that the current mainstream in the EP – composed of the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) – will no longer have the absolute majority they need to adopt new international trade agreements, nationalists could significantly slow down the EU’s external trade agenda. This would curb the union’s ability to use trade as one of its major instruments for boosting prosperity in Europe and pursuing its foreign policy goals.[2]

The rule of law

One of the key procedural powers that flows from controlling at least 33 percent of EP seats is that to block the EU’s Article 7 mechanism, which is designed to defend the rule of law in member states. Currently, Article 7.1 procedures are open against the governments of Poland and Hungary. In September 2018, the EP voted by an overwhelming margin – 448 to 197, with 48 abstentions – that there was a “clear risk of a serious breach” of the EU’s values in Hungary. The matter then went to the Council, which, before making a determination about whether there is such a risk, must hear from the Hungarian government, make recommendations to it, and assess its response. In the case of Poland, the procedure was initiated by the Commission. But, in March 2018, the EP voted by a large majority – 422 to 147 – in favour of a non-binding resolution that supported the Commission’s decision to trigger Article 7 against Poland for undermining the independence of the judiciary, calling upon the Council to swiftly determine whether there is a “clear risk of a serious breach” of the EU’s values.

This shows the extent to which progress with the EU’s rule of law procedures depends on the support of both the EP and the Council – which is one of the reasons why the Article 7 mechanism is mostly an instrument of political pressure rather than anything that could realistically lead to the suspension of a member state’s voting rights. But that is exactly the point: with the EP unable to initiate rule of law investigations against member states, and with a rising number of member states in the Council represented by governments that are reluctant to support it either, the EU would have severe limits on its capacity to defend democracy within its borders. And such procedures could even be completely blocked if some anti-European parties successfully translate their gains at the EP election into a position in government at home (as seems possible in Denmark, Estonia, and Slovakia). Aside from its internal consequences, such a development would further erode Europe’s global credibility as a champion of democracy and the rule of law.

Migration

The EP has mostly non-legislative competences in migration policy – one of the issues on which anti-European parties focus. The EP has a consultation (rather than co-decision) role in this area. In those subject to the consultation procedure, the Council has to ask the EP for its opinion. It is not legally obliged to take the opinion into account. However, in line with the case law of the European Court of Justice, it must not take a decision without having received the EP’s opinion, which is decided by a majority vote. That said, the EP can make things difficult for the Council. Firstly, it can refuse to give an opinion – which prevents the Council and the Commission from proceeding. The EP can also delay proposals it does not support by referring them back to committees. Secondly, insofar as the Commission can amend the proposal until the moment of final agreement by the Council, the EP will often aim to exert pressure on the Commission to secure its agreement on amendments the EP supports.

Still, apart from providing opinions, the EP has been increasingly active in adopting non-binding resolutions on issues where it lacks a co-decision role – including most aspects of migration. For example, on 12 April 2016, the EP adopted a resolution on “the situation in the Mediterranean and the need for a holistic EU approach to migration”. Therefore, the major threat to the EU’s migration policies stemming from the 2019 EP election is that, with many more anti-immigrant MEPs present in the next parliament, their voices would become much stronger than they are today, which could limit the capacity of member states and the Council to seek a humanitarian and solidarity-based approach towards migration challenges – instead of securitising the issue. As on the rule of law and free trade, this would limit the EU’s credibility to contribute to the resolution of challenges in other regions of the world and at the global level.

Foreign policy

Despite its limited competences, the EP is increasingly active on foreign policy issues. The EP’s committee on foreign affairs has more members than other committees and is one of its most active. Between July 2014 and December 2017, it adopted 58 reports on its own initiative – almost twice as many as the economic and monetary affairs committee, the second most active one (although the latter adopted many more legislative reports and delegated acts).

Usually, the EP’s activity on foreign affairs takes the form of resolutions that are subject to majority voting. The importance of these resolutions varies depending on the issue or region in question. For example, they are closely followed by accession countries such as Montenegro. This is related to the EP’s “power of the purse”: it has a crucial voice on the allocation of accession funds to candidate countries. But EP’s resolutions on other issues – including China, the US, and Russia – are also important, as they are increasingly perceived as an expression of the EU’s foreign policy. This is why the EP must demonstrate as wide support as possible for any resolution it adopts.

Although they are non-binding, such resolutions are also one of the tools with which the EP can influence the EU’s foreign policy – through both the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the Council. Its other tools for this include budgetary pressure (given that the EP has to approve EEAS budgetary and staff changes) and regular hearings with the high representative for foreign affairs and security policy. Thus, even without holding many seats in the EP, nationalist parties can obstruct processes in this area. For example, given the usual insistence on looking for the widest possible support on the EP’s foreign policy resolutions, they could table a long list of amendments to either delay the process (after which they could still vote against the motion) or water down the final text – a tactic that members of the far-left European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) group have sometimes used.

EU budget

The EP has a crucial role in shaping the EU’s Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), in three respects. Firstly, while adopting a proposal from the Council formally requires only the EP’s consent, Article 312(5) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union enables the EP to also participate in the negotiating process around the MFF. This requires the EP, the Council, and the Commission to take any measure necessary to facilitate the adoption of the MFF. The support of a majority of the EP’s component members is needed for the adoption of the MFF. Secondly, following the ordinary legislative procedure, the EP has a strong role in deciding what the MFF will allocate to various programmes and funds. And, finally, the EP needs to issue an opinion on the EU’s resources within the MFF. While this gives it a relatively limited role, the EP has so far presented these three elements as a single package, strengthening its role in MFF negotiations.

The EP also plays a key part in the allocation of expenses in the EU’s annual budget. The Lisbon Treaty eliminated the distinction between compulsory and non-compulsory expenditure, putting the EP on an equal footing with the Council in this. The EU’s annual budget is now subject to a form of the ordinary legislative procedure. The EP is involved in the budgetary process from the preparation stage, notably in laying down guidelines and determining types of spending.

Finally, the EP also makes extensive use of its budgetary powers elsewhere. For example, the EP has a de facto veto over the design of the EEAS, as it must approve the organisation’s budgetary and staff changes. In this way, the EP may have an impact on the priorities of the EU’s foreign policy. All in all, whoever controls the EP’s majority has significant budgetary tools at their disposal to shape the EU’s priorities, as well as its policies (by, for example, limiting the funds available to various areas of foreign and development policy).

Brexit, the EP election, and the end of the current MFF will come in quick succession in 2019 and 2020. This creates intense pressure to adopt the next MFF, together with the accompanying spending plans for various sectors, as soon as possible. But the EU seems unlikely to reach even a rough agreement on the next MFF before the election, meaning that MEPs from anti-European parties in the next parliament will be able to exert pressure on the size and shape of the EU’s next multiannual budget. Of course, these talks are always difficult, as they set net contributors and net beneficiaries against each other – as they do supporters of various elements of the budget, ranging from cohesion policy, agricultural funds, and research to migration, the eurozone, and defence and foreign policy. Nonetheless, an EP in which nationalists have a strengthened voice may only add an additional hurdle to an already complicated process – even if they pursue contradictory goals such as shrinking the budget, increasing cohesion funds, and defunding foreign policy and development projects. In this scenario, there is a heightened risk that the EU’s foreign policy will fall victim to cuts or compromises.

Appointment of the next Commission

The result of the May 2019 election will be instrumental to the composition of the next European Commission (the EU’s main executive body), including the president and the high representative for foreign affairs and security policy. Once the Council nominates a candidate for the president of the Commission (with a qualified majority), he or she will need to be approved by a majority of the EP’s component members – that is, at least 353 of 705 MEPs in the post-Brexit EP. If the candidate does not obtain the required majority, the president of the EP will invite the European Council to propose a new candidate, who would have to follow the same procedure. In 2014, a Spitzenkandidat was appointed for the first time, with the Council’s nomination of Jean-Claude Juncker (the leader of the winning EPP group) as candidate for the presidency of the Commission. This practice is meant to not just provide democratic legitimacy to the EU’s executive, but also to facilitate the EP’s approval of the nominee.

The next step is the election of the entire College of Commissioners. Here, the EP has a significant opportunity for disruption. The EP elects or rejects the College of Commissioners as a whole, in one vote, with a majority of votes cast. However, prior to this, the commissioners-designate appear for hearings before parliamentary committees in their prospective fields of responsibility. Each committee meets to produce an evaluation of the candidate’s expertise and performance, which is then sent to the president of the EP. The threshold for suspending the process of nominating a candidate is relatively low: more than one-third is enough to hamper the committee’s approval of a candidate. The candidate may still be elected as part of the entire College of Commissioners in a plenary vote. However, a negative evaluation has prompted previous candidates to withdraw from the process.

Although it is up to member states to propose commissioners-designate, the presence of anti-Europeans in several national governments poses a serious risk that the next European Commission will become less internationalist and principled on the main global issues Europe faces, such as free trade, human rights, the rule of law, and multilateralism. But the result of the 2019 EP election will also be decisive for whether and how the selection of the president of the European Commission will follow the Spitzenkandidat procedure. (For example, the appointment of the EPP’s Manfred Weber as the next president of the EP could mean various things depending on which political groups support him.) And it would have an impact on the chances for candidates with a relatively internationalist world view – such as the next high representative – to obtain a positive evaluation in committee. In short, the European Commission’s foreign policy outlook also depends on this election.

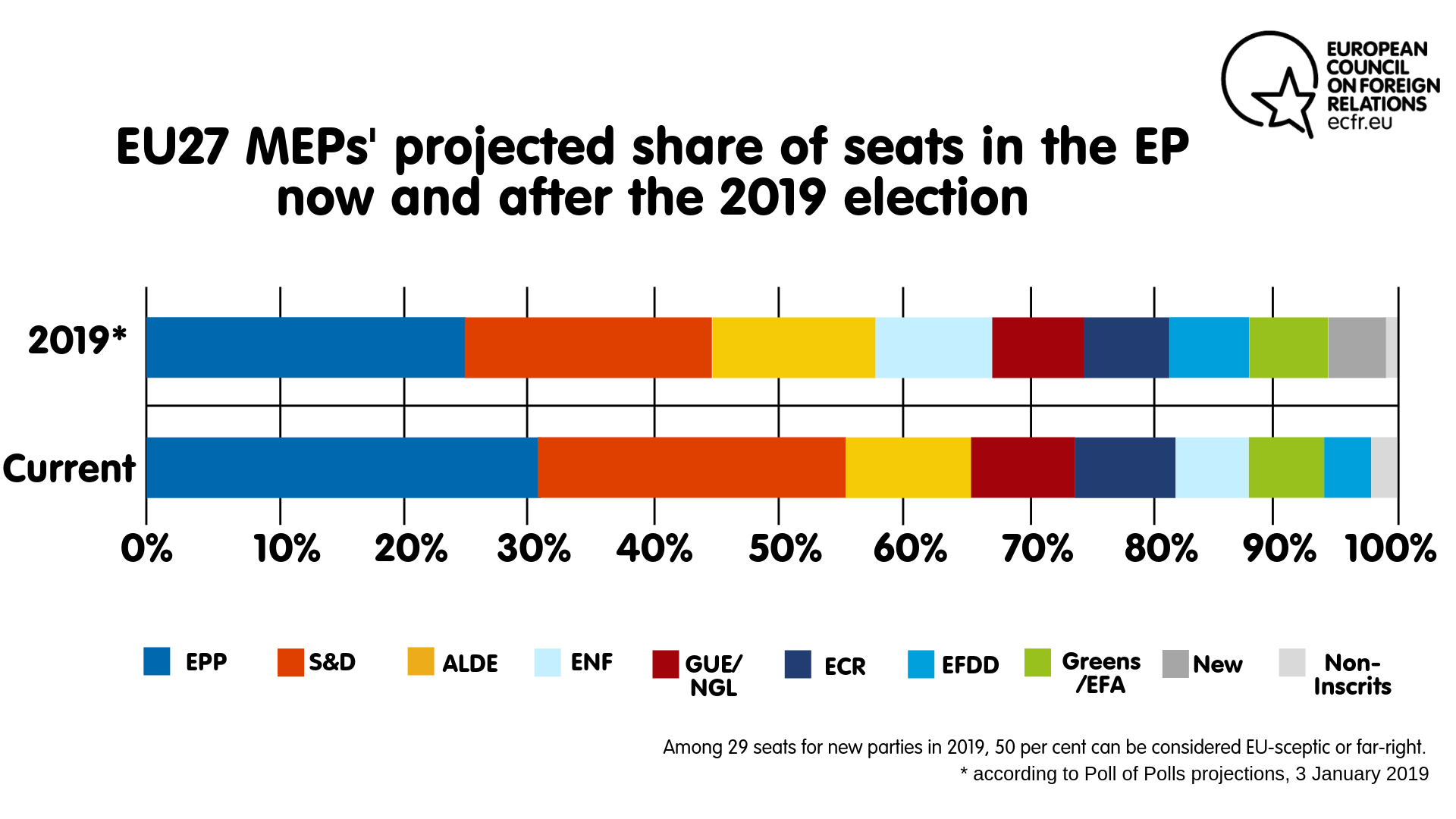

The spoils of cooperation

Anti-European parties’ capacity to obstruct the work of the EP in the ways described above will largely depend on whether they can coordinate their activities with one another – something that has never been one of their strengths. According to current polls, a variety of anti-European parties ranging from the far left to the far right, including right-wing Eurosceptics, are for the first time almost certain to acquire more than one-third of EP seats. More worryingly, the collective seat share of representatives from the far right and right-wing Eurosceptics will, if current polling is accurate, rise from 23 percent to 28 percent. They could even gain more than 30 percent of seats if their popularity continues to grow or if some of the fringe members of the mainstream join them. If they cross the one-third threshold, this would signify a qualitative change in the EU. ECFR’s calculations in this paper assume that the UK will not participate in the May 2019 election. However, as an extension to Article 50 negotiations seems a distinct possibility with the lack of clarity on the UK’s position, the participation of British MEPs in May 2019 could throw another spanner in the works.

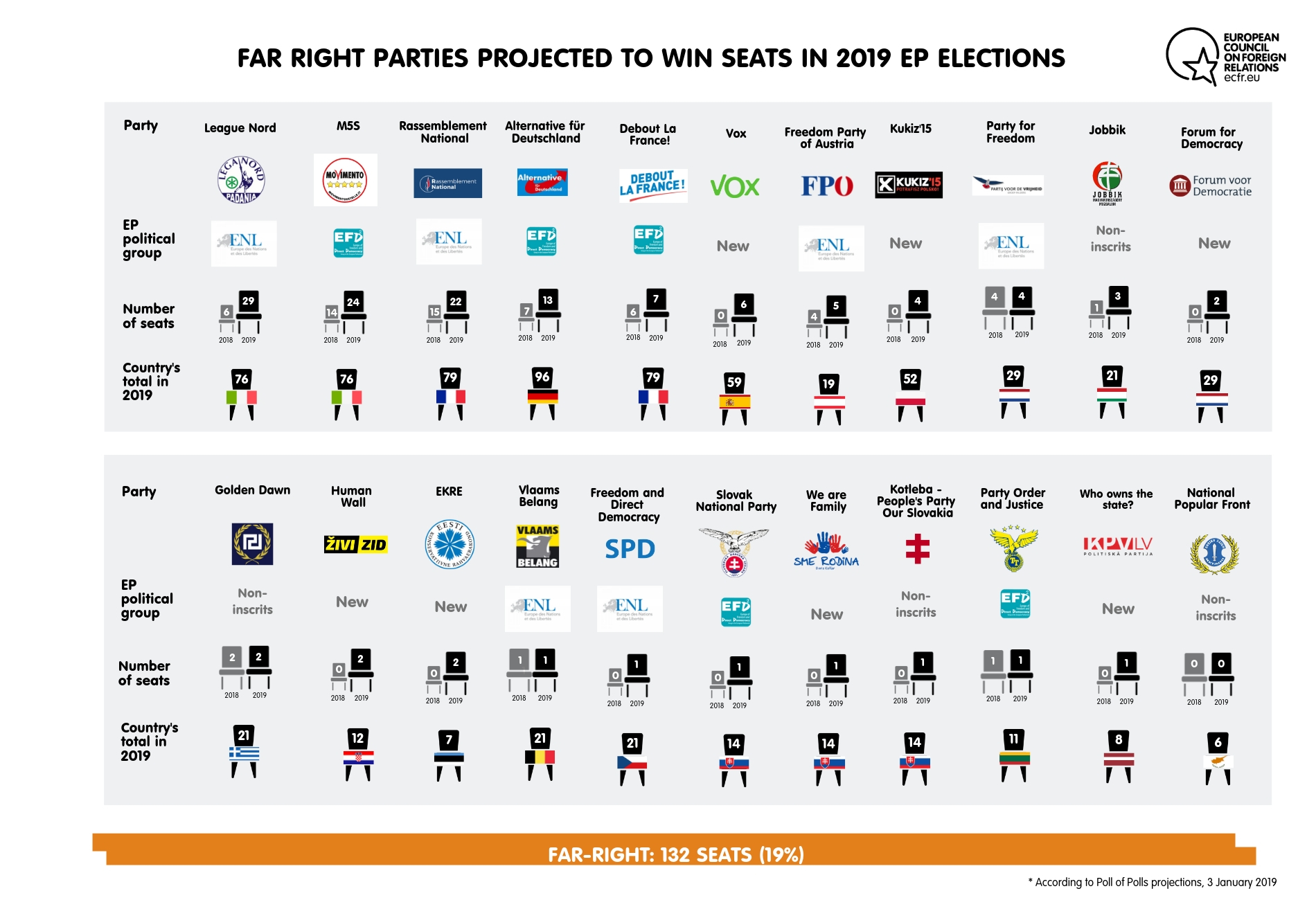

What types of cooperation between parties are possible? To start with, a die-hard anti-EU coalition of only the far right – including Rassemblement National leader Marine Le Pen and the UK’s Nigel Farage, as well as Greek and Hungarian nationalists – currently holds slightly more than 10 percent of EP seats. This share may rise to 19 percent next year, largely due to the expected success of Rassemblement National, Alternative for Germany, and Italy’s League (as well as that of the Five Star Movement, which may not align with the EP’s far right). Most far-right MEPs are affiliated with one of two political groups in the EP – Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD) and Europe of Nations and Freedom – or are non-aligned. So far, the far right has been divided, due to ideological and personal issues. These two political groups have demonstrated very weak internal cohesion relative to most others in parliament. And this lack of unity has often prevented the far right from affecting European processes (as has their reluctance to actively participate in the EP’s daily work). But this could change if they double their share of seats.

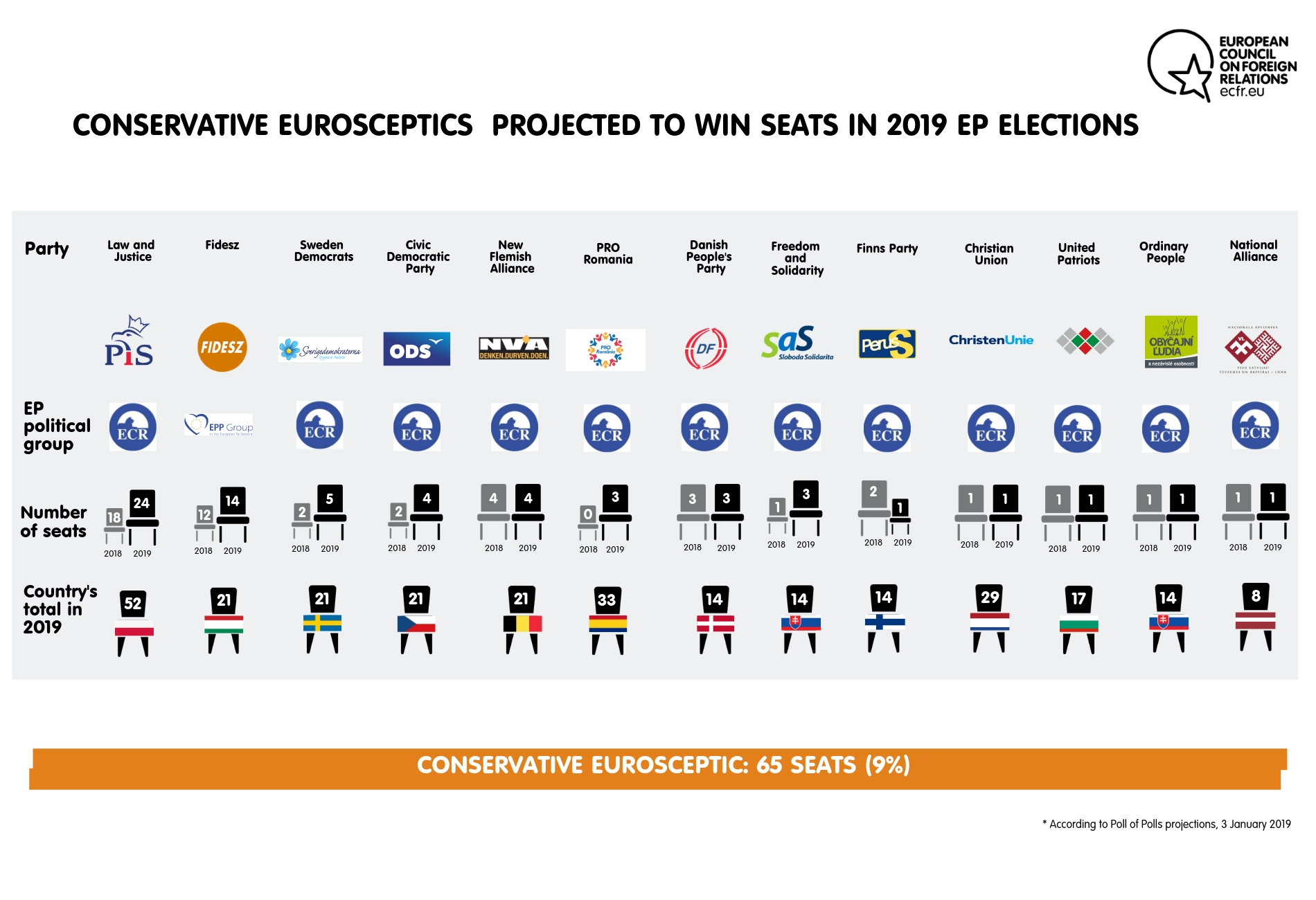

This core far-right group could also ally with MEPs from Eurosceptic parties on the right, particularly those in Scandinavia and central Europe. These parties include Poland’s PiS, the Sweden Democrats, and the Danish People’s Party – all of which are currently affiliated with the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group in the EP – as well as Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz, which remains a member of the EPP.

Members of a possible coalition of the far right and conservative Eurosceptics would find it relatively easy to cooperate with one another on the issues they care about most, particularly migration and the rule of law. They may disagree on some foreign policy issues: the pro-Russian stance of Le Pen and the League’s Matteo Salvini has discouraged PiS leader Jaroslaw Kaczynski from joining a unified sovereigntist block in the run-up to the EP election. But they may still put their differences aside to reach two shared tactical goals: curbing the EU’s liberal orientation and returning power to member states.

Europe’s right and far right could even formally establish a new political group, which would be the second-largest political family in the EP. In any case, the right and the far right will likely be forced to realign in 2019 due to the loss of British MEPs and to requirements for forming a parliamentary political group that the ECR and the EFDD may struggle to meet. Furthermore, it is unclear whether Fidesz will leave the EPP. As it stands, neither Orbán nor the EPP have an interest in announcing a divorce before May 2019. But, after the election, there is a high likelihood that the nationalist camp will become more unified.

Finally, there is also a possibility of an “all against the establishment” alliance of the far right, Eurosceptics, and the far left. If parties such as Germany’s Die Linke and La France Insoumise joined the cause, this coalition could make life very difficult for pro-European forces given that, for the first time, they are almost certain to collectively win more than one-third of MEP seats.

The far right and the far left have worked together in the EP before, largely in areas where either the ECR voted with the mainstream (such as on Russia, the US, and trade) or the mainstream demonstrated significant internal discipline (such as on migration). Love of Russia, hatred of sanctions, and strong protectionist inclinations can unite the far left and the far right. Nonetheless, it is still more common for them to take different approaches. For example, in September 2018, most MEPs affiliated with the far-left GUE/NGL voted with the mainstream in favour of the Sargentini Report, which criticised Orbán’s government for undermining the rule of law in Hungary.

Therefore, opportunities for cooperation between the far right and the far left are limited and will vary from party to party. For example, Portugal’s Left Bloc may be critical of the EU in many ways, but it also aims to counter xenophobia and nationalism in Europe. Podemos and Syriza have been much more willing to cooperate with mainstream parties on European issues since they became part of their countries’ political establishments. In turn, La France Insoumise could play a different role: its leader, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, refused to tell his supporters not to vote for Le Pen in the second round of France’s 2017 presidential election.

In this context, a significant threat to the European project comes not so much from an “all against the establishment” alliance (especially given that the far left have few things in common with the Eurosceptic right), or from a stable alliance between the far left and the far right, but rather from unplanned alignment on key aspects of the EU’s agenda, or a readiness to cooperate on the two tactical goals discussed above. Whenever the far right, the far left, and the EU-sceptic right vote together, the mainstream will have a relatively slim margin of error, forcing it to be disciplined and to build coalitions around individual issues. In recent years, pro-Europeans across the political spectrum have rarely exercised such discipline.

The ideal opponent: where defenders of the European project are going wrong

But what would cooperation between anti-European parties in the EP mean in the real world? Politics across the EU – from the gilets jaunes (yellow vests) stand-off in France to the election of EU-sceptic governments in Hungary, Italy, and Poland – demonstrates that an increasing number of voters see no link between negotiations in the corridors of power and the issues they care about: jobs, security, and living standards. Can the threat that the election poses be brought to life?

Allowing anti-Europeans to frame the debate

Arguably, in a world where tweets can dictate policy and easy promises of change increasingly draw votes, the ideas that mobilise the anti-European camp can have a much simpler appeal than arguments for a united, internationally engaged Europe. Le Pen claimed in October 2018 that “we are not fighting against Europe, but against the EU, which has become a totalitarian system.” Together with Salvini and Orbán, she will harness the power of this kind of confrontational imagery to lead Europe’s nationalists. Regardless of whether they eventually receive logistical support from the Movement (a pan-European organisation created by former US presidential adviser Steven Bannon in anticipation of the 2019 EP election), they are already uniting behind three main beliefs: EU institutions have too much power, European citizens want governments to place a greater emphasis on security, and Europe requires tighter border controls.

However, it is the third belief – and the topic of migration more broadly – that is becoming the main focus of their campaign. According to Orbán, “the conventional division of parties into those of the right and of the left will be replaced with a division between those which are pro-immigration and those which are anti-immigration”. This framing enables anti-European parties, mostly those on the right, to strengthen their sense of internal unity and to reach out beyond the core anti-EU electorate. Therefore, it would be a mistake to assume that anti-Europeans will have no influence on the EU’s approach to migration just because they are disunited on the specifics of migration management policy. Indeed, the political fear that they have generated on migration in almost every EU member state in recent years – which has caused mainstream parties on the right and the left to advocate increasingly draconian approaches to migration management – testify to the power of this issue for them.

To date, the Movement has only rallied a handful of Europe’s 40 or so anti-EU parties to its cause. But its relentless focus on the core message and its targeted, well-funded media campaign appear to have lent it considerable momentum. The performance of the far-right Vox party in a regional election in Andalusia last year – in which it obtained 11 percent of votes and 12 out of 109 seats in the regional parliament, allowing it to join a regional coalition – provided the Movement with a significant success story. The organisation also benefits from the alignment of its objectives with those of the American alt-right and the Putin government, as well as a worldwide revolutionary zeitgeist evidenced by the latest presidential elections in the US and Brazil. Given the Russian interference in recent national elections in Europe, and the tension in EU-Russian relations arising from hostilities in the Sea of Azov in November 2018, it is highly likely that Moscow will attempt to manipulate the EP vote.

If the nationalists’ focus on migration is well chosen, this is because the issue not only resonates with voters but also demonstrates the divides within the much larger pro-European camp. It seems that most European voters would prefer to reduce immigration, but they differ on how, and to what extent, they should do so. This has prompted pro-European parties to deal with these voters as distinct camps. Not so the anti-Europeans. ECFR’s research confirms that in all EU member states except Portugal, Ireland, and Lithuania, migration will feature prominently in the debate on the May 2019 election. And there are signs that mainstream parties – mostly members of the centre-right EPP – are already conceding ground on migration. With Eurosceptic forces having taken them to task on the issue, moderate parties increasingly appear to view a relatively hard line on migration as the price they must pay to retain power.

This has been clear since the adoption – by a margin of 459 votes to 206, with 52 abstentions – of the resolution on “the situation in the Mediterranean and the need for a holistic EU approach to migration” in April 2016. Providing an overview of the EP’s main positions on asylum, the resolution passed thanks to the support of the EPP, the S&D, the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), and the Greens. However, the EPP’s internal cohesion was relatively low: 33 members of the grouping – including representatives of Hungary’s Fidesz and Romania’s National Liberal Party; several Czech, Slovak, and Latvian MEPs; and even one member of France’s Les Républicains – voted against the resolution. Within the S&D, four Czech social democrats rebelled. Even though the resolution was adopted, the episode demonstrated anti-immigration parties’ capacity to play on divisions within the pro-European camp.

Nationalists also find it relatively easy to divide the pro-Europeans on other issues, such as the rule of law and the EU’s economic governance. The Sargentini Report passed by a margin of 448 votes to 197, with 48 abstentions. But more than one-quarter of EPP members – including some from not just Fidesz but also Germany’s Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU), Forza Italia, Les Républicains, Bulgaria’s GERB, and Spain’s Partido Popular – voted against it.

In what may be another sign that they are bowing to Eurosceptics’ wish for less European economic governance, members of the EPP often vote against one another on issues involving the eurozone. For instance, in a parliamentary vote on the eurozone budget held in 2017, there was a clear divide between representatives of eastern and western countries within the EPP. In comparison, representatives of the centre-left S&D, the ALDE, and the Greens were much more cohesive, largely supporting the introduction of a eurozone budget. Nonetheless, left-wing parties’ persistent divisions on trade liberalisation could lead some of them to partner with Eurosceptics, perhaps paving the way for a more protectionist Europe after Brexit.

Therefore, unless they recognise the existential challenge they face, members of Europe’s political mainstream will struggle to work together against an attack from anti-European parties that seeks to polarise voters on any of these issues. The table below sets out the broad manifesto of anti-European parties – no one party holds all these positions, but each issue could become a focal point for cooperation between them if they see an advantage in it after the election.

Despite their different ideological traditions, pro-European parties will need to become more open to compromise with one another to collectively defend the European project. They will also have to try harder to preserve the internal cohesion of their EP political groups to avoid losing their distinct identities. One of the challenges for them in the election campaign and the next EP will be to define and defend core European values – what voters view as the EU’s greatest strengths – while sustaining a pluralist political debate. These are issues that ECFR will explore at a granular level through quantitative and qualitative public surveys across the EU in the coming months, laying the groundwork for more effective pro-European strategies in the election and afterwards.

Underestimating the importance of the upcoming election

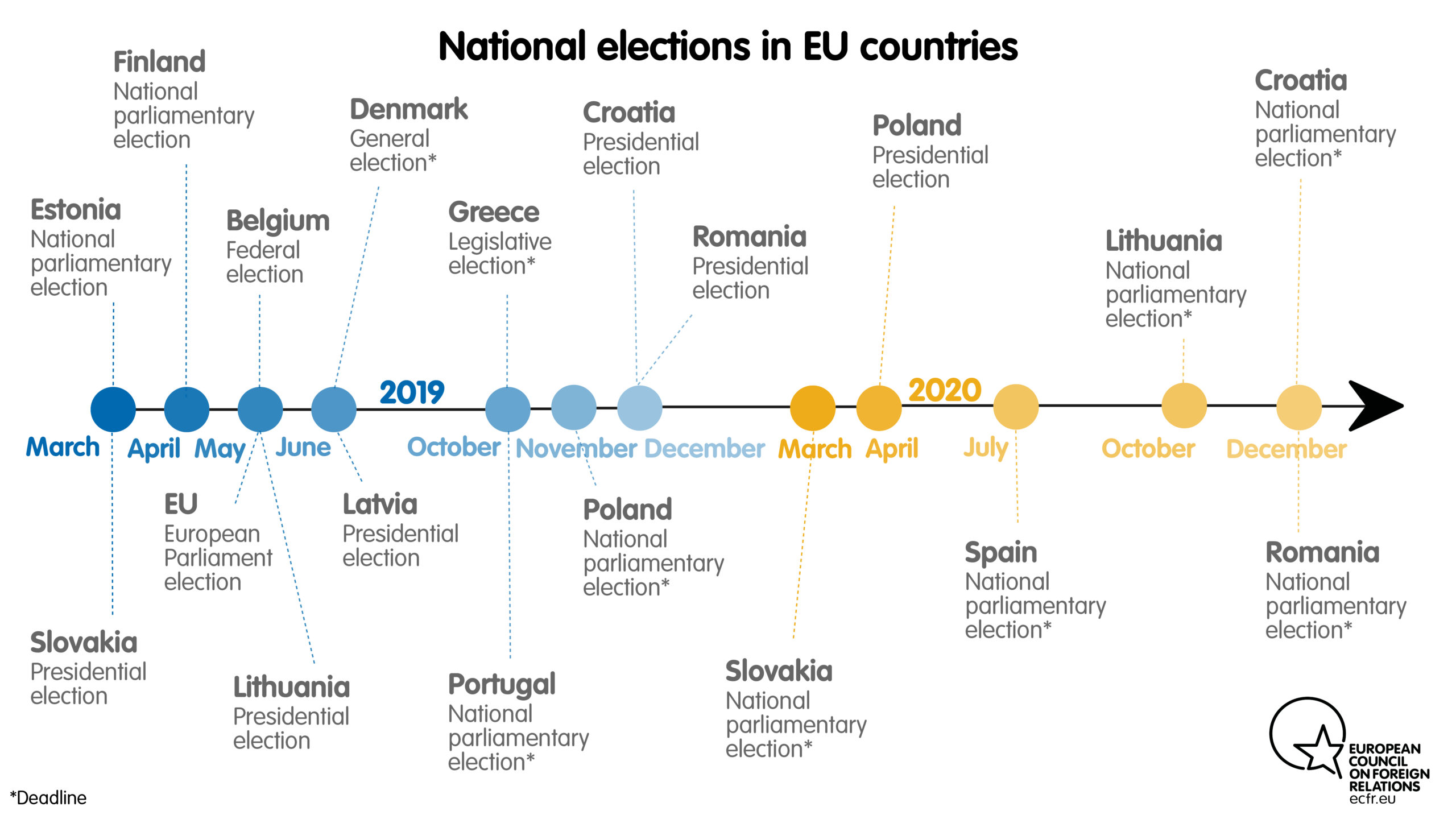

For anti-European parties, winning more seats in the May 2019 election should be understood as a means to an end. The bigger prize for them is a position from which they can challenge pro-Europeans in a wider battle of ideas. They mean to use this as a springboard for fighting national elections across Europe in the coming years.

For instance, if it is successful in the EP election, PiS will improve its position in the run-up to Polish parliamentary vote scheduled for autumn 2019. Equally, a poor result for the party would increase the likelihood that Kaczynski, Poland’s de facto leader, will soon lose power. In Bulgaria, the outcome of the EP election may determine whether the government will hold a snap national election. Such a vote could occur if the ruling, centre-right GERB performs poorly in the EP election, precipitating a political crisis. While GERB has signalled rapprochement with Orbán in the past year, a new election could pave the way for a government led by the Socialist Party, which is a far more strident advocate of anti-immigration and nationalist policies (and more pro-Russian) than its rival.

The EP election could also have a significant effect on Denmark’s political dynamics. With the country planning to hold a national election by June 2019, its mainstream Social Democrats have increasingly adopted an anti-immigration and Eurosceptic posture. And the populist Danish People’s Party stands a chance of entering the next government (having provided parliamentary support to the current one). A similar pattern may emerge in Belgium, with the conservative New Flemish Alliance (the country’s leading party) growing increasingly anti-immigrant ahead of a federal election scheduled for the same day as the EP election. In December 2018, the party’s ministers quit the government in protest against Belgium’s participation in the United Nations’ Marrakesh migration pact.

In Finland and Estonia, the EP election will likely coincide with fresh negotiations on forming a coalition government, raising the prospect of the far right forming part of the next Estonian government. And, by 2020, there will have been a new parliamentary election in Greece (with an early election in May 2019 increasingly likely), Croatia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Portugal, and Spain. There is also a growing possibility of a snap election in Italy, which would almost certainly benefit the League.

All in all, if Eurosceptics retain their power in Poland and Italy and acquire at least some influence over ruling coalitions in countries such as Denmark, Estonia, and Slovakia, this could help the illiberal camp obstruct the EU’s work through the European Council. In this scenario, governments in Budapest, Warsaw, and Rome would feel empowered by association, perhaps helping them break EU rules with impunity. And the risk is all the more serious given that the European Council (which is already a dominant player in the EU’s inter-institutional power game) could gain even greater power after the May 2019 election – at the expense of an EP that will likely be grappling with nationalist parties.

This suggests that neither pro-European parties nor their supporters can afford to indulge in the usual complacency about the importance of the EP election (which, in the past, may have been somewhat justified). In an ideal scenario, their goals of winning both European and national elections should be mutually reinforcing. But there is a risk that some generally pro-European parties – such as those in Denmark, Belgium, Spain, Austria, and the Netherlands, to name just a few – will enter into a vicious spiral: flirting with populist ideas ahead of the May 2019 election to strengthen their position at home. This would only provide more legitimacy to these ideas in a broader European debate and could later backfire at home, if voters decided that they preferred the original to a copy – switching their support from Partido Popular to VOX; from the New Flemish Alliance to Vlaams Belang; from the Austrian People’s Party to Freedom Party of Austria; from Les Républicains to Rassemblement National; from the CDU/CSU to Alternative for Germany; and from Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte to Geert Wilders or Thierry Baudet, leaders of the Party for Freedom and the Forum for Democracy respectively.

Fighting back

Despite the scale of the challenge they face, internationalist Europeans should not give up on this fight before they have even properly begun. Below, we lay out a strategy to prevent the EP election from setting off a broader shift in the European political landscape. The strategy centres on the following ideas:

- Driving a wedge between anti-European parties.

- Demonstrating the costs of their proposals in the real world.

- Framing the election within a pro-European agenda.

Driving a wedge between anti-European parties

As discussed above, the anti-European camp is much more divided than meets the eye. During the EP election campaign, pro-European forces should expose these divisions to undermine nationalists’ capacity to cooperate. They could even play one anti-European party against another – using tactics similar to those that have divided the mainstream.

For example, while the parties of Orbán, Kaczynski, and Salvini may all agree that migration is the EU’s major problem, they seek radically different solutions: the Hungarian and Polish governments refuse to accept the relocation of immigrants to their countries, while the Italian government seeks greater cooperation and solidarity between European states in relocating immigrants. Salvini and Kaczynski also hold irreconcilable views of the EU’s policy on Russia. The former does not conceal his admiration for Putin, while the latter views Russia as posing the greatest threat to his country. Unsurprisingly, they also disagree on NATO. The Austrian, German, and Dutch far right would like to slash the EU’s structural funds, which continue to be a crucial source of revenue for the Eurosceptic governments of Italy, Hungary, and Poland.

Some anti-Europeans are reluctant to address climate change, while others are not. And while anti-immigrant parties in central and southern Europe (including those in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Italy, and Spain) are deeply conservative about social issues – such as LBGT rights – this is not always the case for comparable parties in western and northern Europe. Last but not least, nationalist parties represent all shades of Euroscepticism: from seeking to abolish the EU outright to disliking the common currency or EU institutions’ focus on rule of law issues, to aiming to reshape the EU from within while maintaining an inflow of structural funds. The mainstream should emphasise these differences, with the goal of destroying the image of a monolithic anti-European alliance that Bannon, Salvini, Le Pen, and others are trying to create to promote confidence in the viability of the alternative they believe they offer.

Anti-European parties have accurately observed that, so far, European countries have been disunited on migration. This is why, during the campaign, pro-European parties should put forward practical policies that enable the EU to cope with the political challenge of migration without putting European values at risk. They should uncover the ambiguities and contradictions in the alternative narrative about migration – on which Orbán and Salvini speak with one voice but have opposing interests. At the same time, pro-Europeans should not let themselves become entangled in an all-encompassing debate on migration. Instead, they should try to extend the discussion to areas such as foreign policy, climate change, security and defence, growth, and jobs, issues on which nationalists are either much more divided or much less appealing, or simply have little to say.

Demonstrating the costs of anti-Europeans’ proposals in the real world

Pro-Europeans should also commit to showing how the EP election will affect voters’ lives. They should make clear that a vote for nationalist parties – as novel and exciting as this may seem – has significant effects in the real world.

Most anti-Europeans heavily criticise the EU for allegedly being an elitist project, undermining national sovereignty, and imposing heavy costs on individual countries. They use the word “liberal” as a grievous insult, even if they mean several different things by it. For the left, liberals are to blame for promoting free trade, globalisation, and austerity policy. For the right, liberals damage traditional values and ignore the dangers posed by migrants, secularism, and changes in gender roles. Like Trump or his Brazilian counterpart, Jair Bolsonaro, European nationalists are usually critical of “political correctness” – to the extent that they present their opposition to women’s rights, LGBT rights, other cultures, or measures to mitigate climate change as a crucial part of a pluralist political debate. They are particularly suspicious of multilateralism, as expressed in the Paris climate agreement and the Marrakesh migration pact. And – despite the cautionary tale of Brexit – many of them continue to lure citizens with a promise that their countries can exit the EU without incurring major costs. Pro-Europeans should spell out the consequences of the policies implicit in nationalists’ manifestos.

Support for anti-European and anti-establishment messages has been growing beyond the core electorate of the far right and the far left, for at least three reasons. Firstly, there is widespread frustration – un ras-de-bol général, as the French call it – among many citizens who are tempted to punish the political establishment at the polling stations. Before the 2016 Brexit referendum, many political commentators believed that voters would gravitate towards the status quo in a pivotal election out of fear of the unknown. But the political landscape has changed: recent national elections in France, Germany, Sweden, and Italy have shown that Europeans are increasingly willing to gamble with a vote against the establishment.

Anti-European forces have been successful in constructing an image of EU institutions as distant, ineffective apologists for a ruthless process of globalisation, and as responsible for much of the hardship that voters have endured in the past decade due to austerity, increased migration, and growing insecurity. Moreover, national elections may underrepresent the level of risk that voters could be willing to take in May 2019, given that Europeans generally see EP elections as being of secondary importance. Even EU membership could prompt voters’ recklessness: a paradox that Ivan Krastev observed in central Europe, asking “why should Poles fear someone like Kaczynski if they know that Brussels will tame him if he goes too far?”.

Secondly, some members of the political establishment hope to stay afloat by adopting elements of the anti-Europeans’ agenda, particularly in veering towards anti-immigrant or EU-sceptic positions. The effect of this is twofold, increasing the potential for cooperation between the centre-right and the far right, and making the leap from mainstream parties to their populist rivals appear smaller.

Thirdly, national and EU leaderships adopt anti-Europeans’ methods when they try to address the EU’s so-called democratic deficit through direct democracy tools – such as plebiscites or consultations – and attach excessive importance to them when they are not fully representative or do not go far beyond the level of isolated opinions. This approach could be seen in the citizen consultations on European issues that various member states organised in 2018, in the hope that this could lead to some kind of grand consensus on citizens’ expectations and the ways in which the EU could satisfy them. But this is a perfect example of a technocratic solution to a political problem.

National and EU institutions will need to play a role in halting the progress of nationalists across Europe. But they should not bypass politics, presenting the EU’s policies as apolitical, pragmatic, and without alternatives – as this would only weaken the mediating role of political parties and civil society. Political parties on the national and European levels must do most of the work. Arguably, one of the main reasons behind the rise of the far left and the far right in almost all parts of Europe is that mainstream parties have often become too indistinguishable from one another.

Attempts to unite the left and the right in a kind of pragmatic alliance have been, at best, disappointing and, at worst, dangerously disruptive for established channels of political activism (as is currently seen in countries such as the Czech Republic, Italy, and France). Mainstream political parties’ task is to insert multiple policy options back into the public debate, on issues ranging from migration to trade, the eurozone, and pan-European solidarity. Political parties will also need to argue that elected representatives are indispensable to making sense of very complex issues, against anti-Europeans’ claim that people can rule directly (as promised by Italy’s Five Star Movement, the gilets jaunes, or the Forum for Democracy).

Framing the election with a pro-European agenda

The success of pro-European parties will also depend on whether they can mobilise the silent pro-European majority through the issues that they care about enough to vote on them. To do this, they need a far deeper understanding of what Europeans are currently feeling as well as thinking, and what this means for how pro-European parties should communicate with them. There are many lessons they should learn from the populists themselves. Deeper research is also necessary to provide an emotional map of Europe, to help pro-Europeans navigate the political landscape and understand the feelings and experiences that drive the opinions expressed in citizens’ consultations. This is one of the goals of ECFR’s work in the coming months.

Rather than simply fight defensively on the issues that anti-Europeans favour, pro-European forces should be creative in constructing an image of a reinvigorated, hopeful European project. And they should frame the election debate in each national setting according to the issues that voters want the EU to deal with there. Our research across the EU27 suggests that there are at least five different approaches that could mobilise pro-Europeans:

- A values election: pro-Europeans should explicitly defend the fundamental values that the silent majority believe in and associate with the EU project, including the rule of law; freedom of expression; and equality in economic, social, and cultural rights. They should make clear the extent to which these are under threat from many nationalist parties.

- A prosperity election: pro-Europeans should stress that nationalists’ promise to bring prosperity to the EU is a false one, and defend the record of EU investment in underdeveloped regions. If paralysis in the EU prevents agreement on the next MFF (and the structural funding it provides), this will have a real impact on voters’ quality of life in many parts of the EU. In some countries, such as those in central, eastern, and southern Europe, Europeans should explicitly make this link.

- A tax justice election: in many member states, pro-Europeans could win votes by emphasising that EU institutions are critical in the fight to ensure that large tech companies pay their fair share of tax. This could be effective given that the growing gap between rich and poor is an issue that has prompted many European protests.

- A green election: issues such as climate change and air quality are high on the agenda in France, Poland, Sweden, and other member states. To mobilise voters who are concerned about these issues, it will be important for pro-Europeans to position themselves as the guardians of the green agenda, and emphasise the risk that the EU will no longer be able to provide multilateral leadership in setting environmental regulations.

- An enemy from within election: the argument that anti-Europeans are doing the job of the Kremlin for them, destabilising Europe from within, could prove powerful among voters who are concerned about evidence of political interference and information manipulation from Russia in recent European elections. Pro-Europeans should draw attention to the foreign policy agenda of many nationalist parties.

In some settings – particularly large cosmopolitan cities; regions in which the tangible benefits of EU membership are still highly evident; and member states unsettled by the turbulent international environment and the unreliability of the US security guarantee under Trump, such as Germany – mainstream parties could also fight an “existential threat to Europe” election. In these settings, the desire for l’Europe qui protège is strong, and the logical case should be made that the EU cannot protect its citizens if the internal destruction agenda of the anti-Europeans goes ahead. All in all, political parties should not shy away from looking for novel approaches that reflect their political orientation while enabling them to move the debate onto a wide spectrum of issues. In this way, they could inspire their countries’ pro-European silent majority.

In the three countries in which anti-Europeans lead the government rather than just pose a distant political threat – Poland, Hungary, and Italy – there are strong reasons for the pro-European forces to emphasise their unity. For example, the Polish government may currently be trying to present a pro-European face, but with Poland’s rule of law controversies far from being resolved, and the European Court of Justice ruling on Poland expected in March 2019, there is a genuine threat that Poland will leave the EU, if only by accident. The Polish opposition must emphasise this if it is to stand a chance of defeating PiS in the EP election, and to establish a lead ahead of a national parliamentary election in autumn this year. However, with many voters worried about the direction in which the EU is moving, Poland’s pro-Europeans cannot focus their campaign on only the spectre of an exit from the EU. Instead, they may also have to redefine Poland’s national interests – on energy, defence, and migration, among other areas – and realign them more closely with the rest of the EU, given the changing regional and global context.

In Hungary, the opposition is much weaker than its Polish counterpart. Nonetheless, a recent wave of protests provides the opposition with some momentum to expose the problems with Orbán’s Europe policy, including his government’s reluctance to join the European Public Prosecutor’s Office.

The situation in Italy is much less clear-cut than that in either Poland or Hungary: there are sharp divisions within the government separate to those between it and the pro-European parties of the centre-left and the centre-right opposition. But the Democratic Party and Emma Bonino’s new Più Europa should question whether the government’s aggressive Europe policy – on economics and migration, as well as their anti-elitist stance – actually benefits the country and its citizens.

Conclusion

The battle of ideas in which Europeans are engaged will doubtlessly continue after the EP election. But the result of the May 2019 contest will largely set the boundaries of this battle for years to come. The key battles in May 2019 will take place in Germany, France, Italy, Poland, and Spain, which collectively account for more than 50 percent of EP seats. Nonetheless, preserving a pro-European majority in the EU in the medium and long term will require hampering the rise of nationalists elsewhere, from Sweden and the Netherlands to Estonia and Croatia.

In this sense, pro-Europeans from all EU member states have no time to lose. EU heads of state and government plan to adopt a new document on the future of Europe at an informal summit in Sibiu, Romania, in May 2019. And there are European leaders who occasionally signal a possible opening, as with Juncker’s recent expression of support for European unemployment insurance. But these efforts are insufficient given the task at hand. Pro-European parties and groupings should realise that the fight is now under way. If they allow Eurosceptics to seize the initiative and frame the discussion, and gain further political momentum at home, this will be a strategic error they cannot recover from.

Annex

About the authors

Susi Dennison is a senior policy fellow at ECFR and director of the European Power programme, which focuses on the strategy, politics, and governance of European foreign policy at this challenging moment for the international liberal order. She previously led ECFR’s European Foreign Policy Scorecard project for five years, and worked with ECFR’s MENA programme on north Africa. Before joining ECFR in 2010, Susi worked for Amnesty International in its European Union office. Susi began her career in HM Treasury in the United Kingdom.

Pawel Zerka is a programme coordinator at ECFR based in the Paris office. He coordinates ECFR’s European Power programme. Pawel holds a PhD in economics and an MA in international relations. His main areas of expertise include EU affairs, Latin American politics, international trade, and Poland’s European and foreign policy. Before joining ECFR in 2017, Pawel worked as an expert in foreign affairs in two private think-tanks in Poland: WiseEuropa, and demosEUROPA-Centre for European Strategy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Open Society Foundation, without whose financial support this research would not have been possible. They would also like to express their gratitude to ECFR’s colleagues, especially José Ignacio Torreblanca, Mark Leonard, and Carla Hobbs for their helpful comments. Special thanks go to Chris Raggett, Adam Harrison, and Katharina Botel-Azzinnaro for editing, and to Marta Pellón Brussosa for research support. This report relies more than anything on the tireless work of our 27 researchers across the EU, to whom the authors are deeply indebted.

[1] For a demonstration of procedural effects of two other scenarios – above 50 percent or below 33 percent – see Annex.

[2] For the explanation of abbreviations and of the political divisions in EP, see Glossary Box at the end of this paper.

Austria

Projected voter turnout

Turnout at the last two EP elections in Austria stood at 45-46 percent. It is unlikely to go beyond that level in 2019 – despite the higher than usual stakes of the vote. There are usually no surprises in Austrian EP elections given that they normally see experienced politicians running for the main parties. At the same time, the ruling coalition may refrain from putting too much emphasis on the poll as Austrian voters have often used EP elections as an occasion to protest against government policy – to the benefit of opposition parties.

Main battles in 2019

Austria is a small political market and, therefore, it will hold a centralised political debate ahead of the 2019 EP election. Migration and security concerns will be the main topics. Chancellor Sebastian Kurz’s Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) – the ruling coalition’s main party – will present itself as one of the key actors in reforming the EU and a guarantor that the country’s borders will be protected against illegal migration. Heinz-Christian Strache’s Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) – the coalition’s junior partner – will campaign more aggressively against immigration and the purported Islamisation of the country. In turn, the main opposition parties – liberals and social democrats – may intend to refocus the debate on socio-economic challenges and are likely to appeal for stronger European cooperation.

The mainstream

The ÖVP is the main political force in Austria, leading the government coalition and polling first with 35 percent of the vote, nine percentage points more than the Social Democrats (SPÖ). The ÖVP is a member of the European People’s Party group within the EP and maintains close links to German conservatives: Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats and Horst Seehofer’s Christian Social Union. The ÖVP favours trade liberalisation and the EU’s focus on the rule of law – but is reluctant to support further EU integration and is internally divided on the issue of migration. It is likely to win seven MEP seats in 2019. The SPÖ is traditionally the other mainstream party in Austria. A member of the Socialists and Democrats group in the EP, it cooperates with the Italian and Spanish centre-left; it may win five or six MEP seats. Mostly in favour of migration, the rule of law, and closer European integration, it tends to be divided on the issue of trade liberalisation.

The Eurosceptics

The FPÖ is the main party of Austria’s far right. The junior partner in the ruling coalition, the FPÖ is strongly anti-immigration and Eurosceptic, opposing not just “ever closer union”, but also the EU’s focus on the rule of law and its trade liberalisation initiatives. Members of the Europe of Nations and Freedom group in the EP, they maintain close links to Alternative für Deutschland, Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National in France, and Law and Justice in Poland. Between 2015 and 2017, the FPÖ led in Austria’s opinion polls but ended up coming third in the 2017 Austrian parliamentary election, with 26 percent of the vote – which is, more or less, its current level of support. The FPÖ is projected to win five MEP seats.

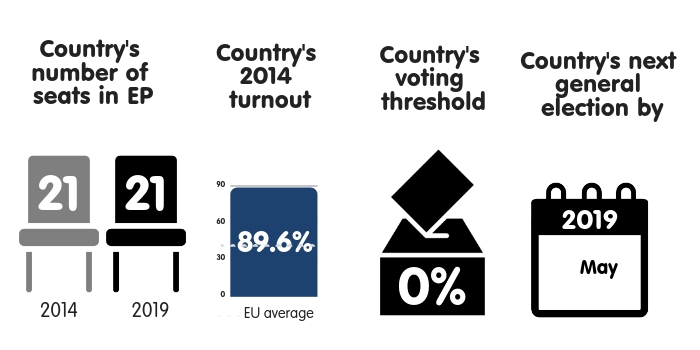

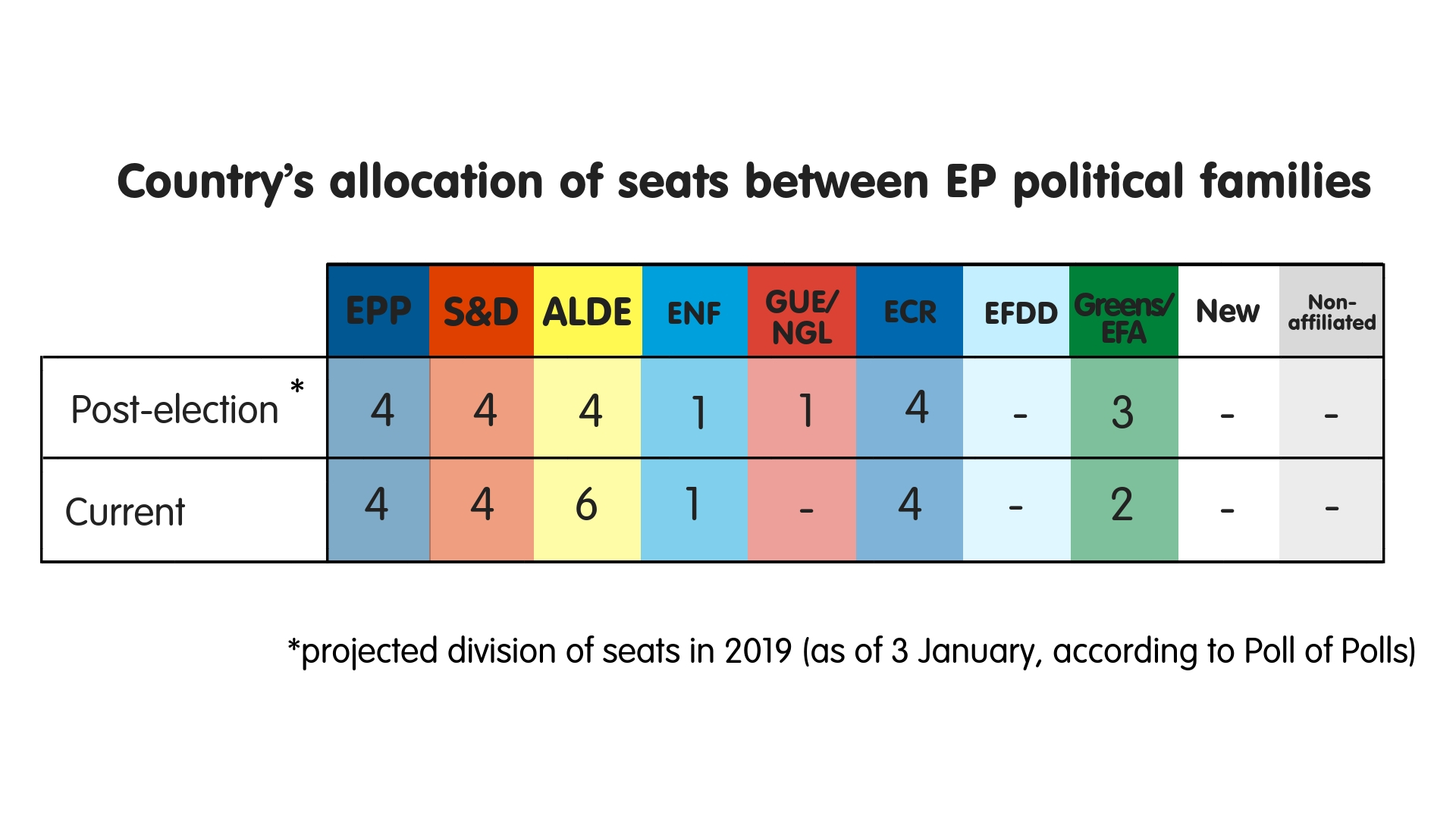

Belgium

Projected voter turnout

Belgium and Luxembourg usually have higher turnouts in EP elections than any other country (regularly more than 90 percent). However, given that voting is obligatory in both states, this is not a useful indicator of voters’ interest in EU affairs. Judging by the low profile of European issues in the Belgian political debate, EP elections are of little interest to voters. That may especially be the case in 2019 due to recent fallout over the Marrakesh Pact, and given that the EP election will coincide with federal and regional elections, which most citizens consider to be much more important. This is quite paradoxical, since some of the most topical issues in the coming national ballot (such as security and the refugee crisis) are, to a large extent, dealt with at the EU level.

Main battles in 2019

Belgium (along with Italy, Poland, and Ireland) is one of a handful EU members that will be divided into several constituencies at the 2019 EP election. Its three constituencies will comprise the Dutch- (12 MEPs), French- (eight MEPs), and German-speaking (one MEP) electoral colleges. At the same time, the debate will be strongly polarised between the country’s three main regions: Flanders, Wallonia, and Brussels. As Flanders is a right-leaning region, migration and security should feature prominently there, especially since these will be the first federal, regional, and EP elections in Belgium since the March 2016 Brussels bombings. Wallonia is a left-leaning region where socio-economic issues will be at the heart of the debate, although migration will feature as well.

The mainstream

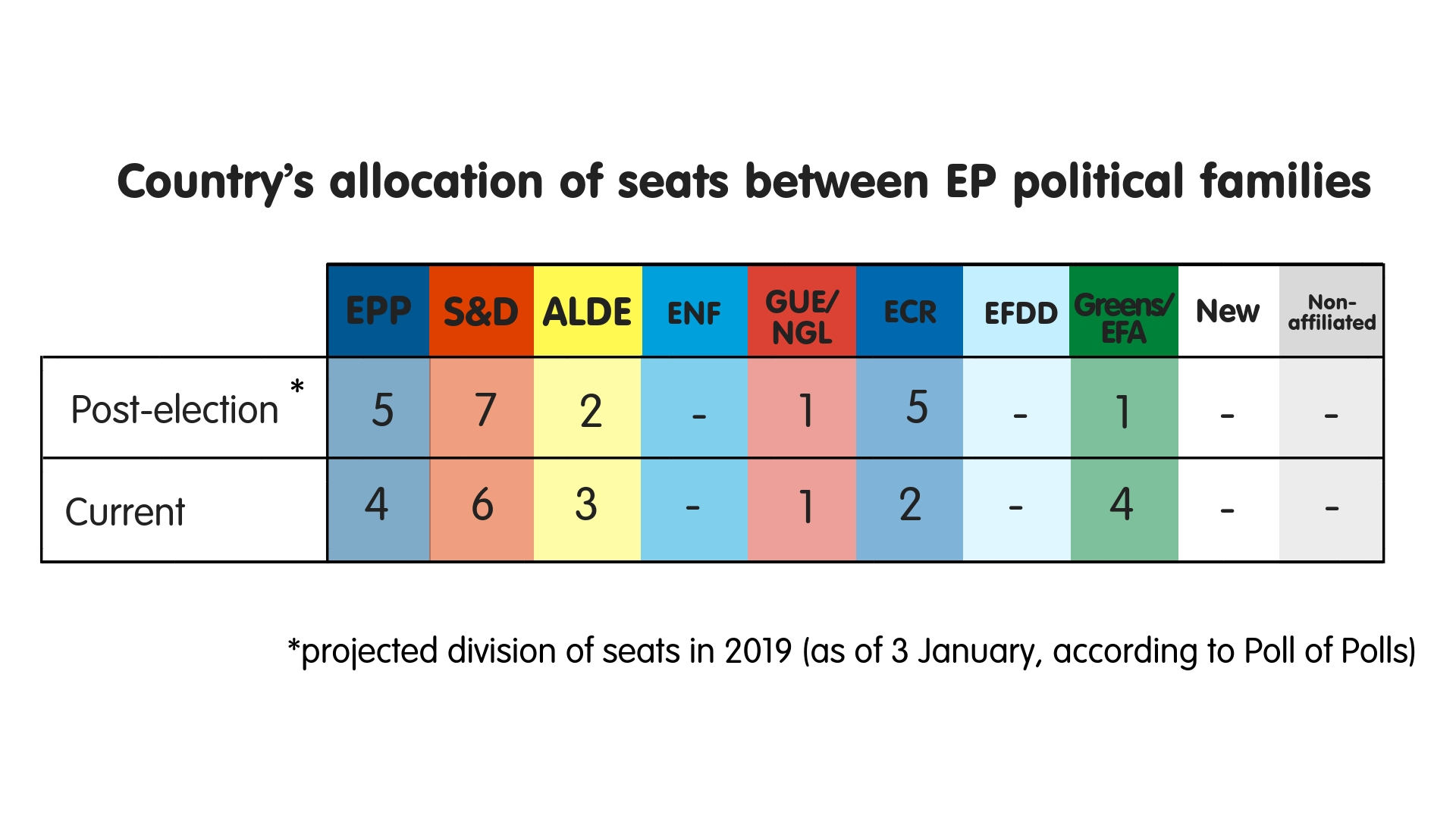

Given the lack of electoral threshold, and the fact that the country is divided into three electoral colleges, Belgium’s political representation in the EP is likely to be something of a patchwork. Altogether, 12 different parties are projected to win one or more seats, half of them just one MEP. Therefore, it makes sense to discuss the projected changes in the balance between representatives in the EP’s political groups. From this perspective, the number of Belgian liberal MEPs may fall from six to four following the decline in the polls of both Le Mouvement Réformateur and the Flemish Liberals (Open VLD). The Greens – who are gaining popularity in Flanders and Wallonia – may add another MEP seat to their current two. Belgian members of the European People’s Party, the Socialists and Democrats, and the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) – which have four MEPs each – should maintain their overall positions.

The Eurosceptics

One dynamic that is playing out on the right of the political spectrum is crucial in Flanders. There, the right-wing New Flemish Alliance (NVA), a member of the ECR, is trying not to lose ground to the far-right Vlaams Belang (VB), a member of the Europe of Nations and Freedom group. As it does so, the NVA is becoming increasingly hardline on migration – and it left the ruling coalition in December 2018 in protest against the country’s support for the UN Global Compact on migration. Current polls suggest that the NVA and the VB will win four MEP seats and one MEP seat respectively, but this may change. Meanwhile, on the left of the spectrum is the far-left PTB/PVDA, which is a member of European United Left–Nordic Green Left group, and which has been critical of the EU. Seeking its first MEP, it has already pulled the region’s Socialist Party further to the left. At a federal level, this growing polarisation will likely complicate the formation of the next Belgian government: the main Flemish party, the NVA, refuses to govern with the main Walloon one, the Socialists.

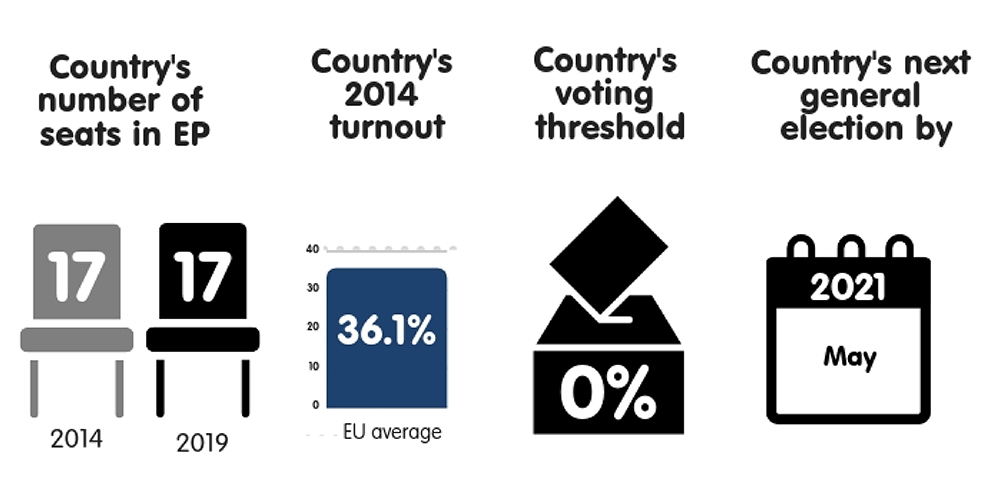

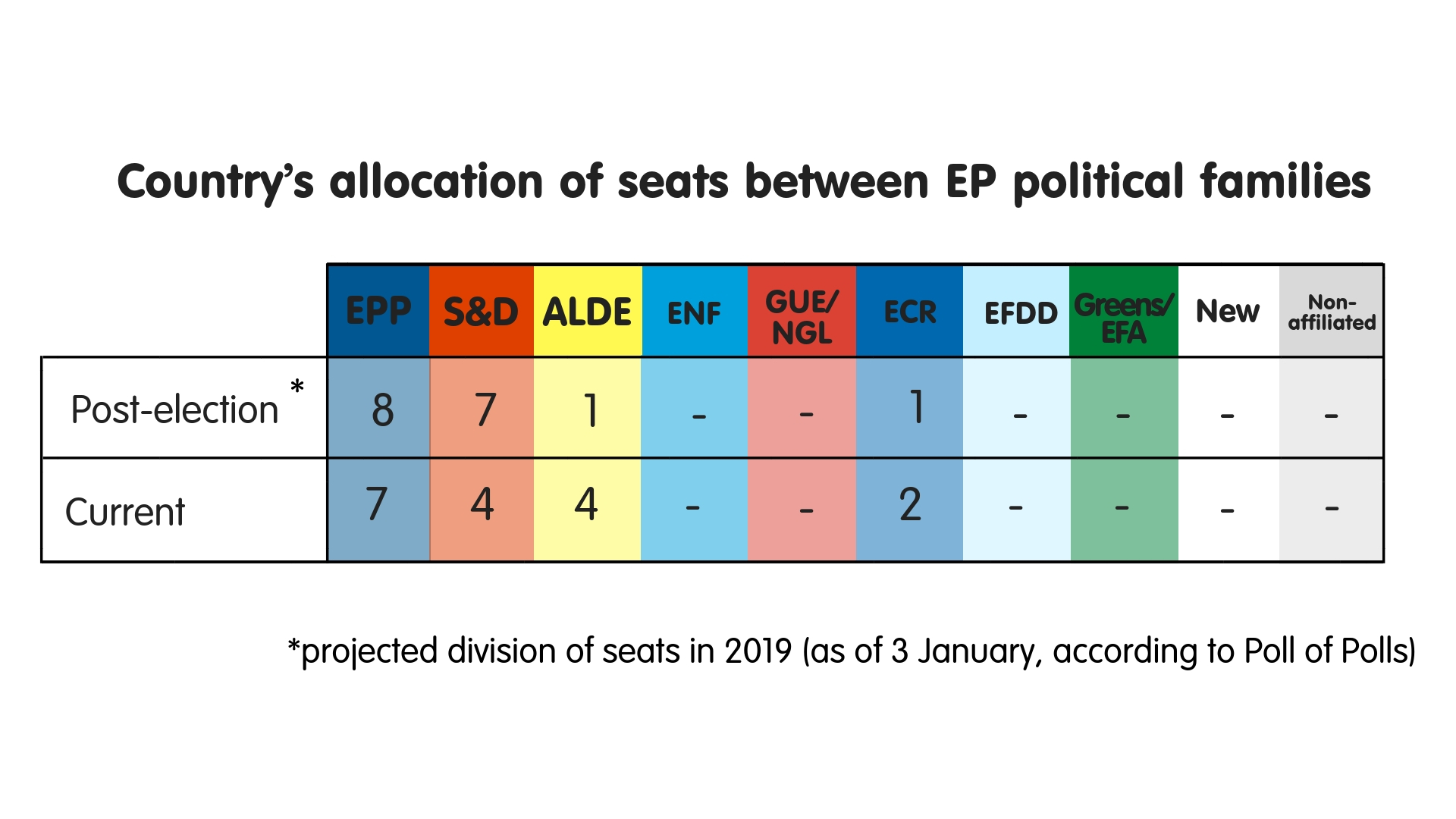

Bulgaria

Projected voter turnout

Most Bulgarians see the EP elections as a continuation of national politics, or as something of a rehearsal for the next general election, rather than a period of in-depth deliberation about the EU and Bulgaria’s membership of it. Bulgarians have not had an opportunity to express their support for political parties since the snap general election in March 2017. Some experts say that the outcome of 2019 EP election will decide whether another snap national election is needed in Bulgaria. This raises the stakes of the 2019 vote and may boost turnout – which was higher in 2014 (at 36 percent) than in most other central and eastern European EU member states.

Main battles in 2019

The campaign for the EP election will focus on a mixture of national and European issues. The ruling centre-right will likely concentrate on the EU’s next Multiannual Financial Framework, as well as cohesion policy, with a positive message about the next round of European investments in Bulgaria. It may also promise further progress on the country’s membership of the eurozone and the Schengen Area. In turn, the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), as the main opposition party, and right-wing United Patriots, a junior partner in the ruling coalition, may focus more on migration and border protection, exploiting a rise in anti-refugee sentiment in the country. They are also likely to criticise the EU’s policy vis-à-vis Russia, given their largely pro-Moscow orientation. There is a consensus among Bulgarian parties that the prospect of a multi-speed Europe should be avoided, but that they should debate the ways in which it could come about.

The mainstream

The ruling coalition is led by Boyko Borissov’s centre-right GERB (a European People’s Party member), which leads the polls with 38 percent of the vote and is projected to win eight MEP seats in 2019. The BSP, members of the Socialists and Democrats group in the EP, is the second-largest party in Bulgaria, polling second at 33 percent of the vote, which would provide it with seven MEP seats. Rumen Radev, who became the country’s president in 2017 with the support of the BSP, is considered a unifying figure for the country’s left, which is strongly pro-Russian. The Movement for Rights and Freedoms (a member of the EP grouping of Liberals) is often referred to as the Turkish minority party and polls third with 8 percent of the vote, which would earn it one MEP seat. All other parties are projected to compete for the one remaining Bulgarian seat in the EP.

The Eurosceptics

Despite representing the mainstream, factions within Bulgaria’s two main parties (especially the BSP and, to a lesser extent, GERB) have veered sharply towards conservative, nationalist, and even Eurosceptic positions in recent years, following the lead of Viktor Orbán’s Hungary. These aside, there are strongly Eurosceptic politicians in Bulgaria – particularly within the United Patriots, which is a loose coalition of three nationalist parties (the National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria, the Bulgarian National Movement, and Ataka), and which serves as a junior partner in the current national government. With 9 percent support in the polls, it hopes to win one MEP seat in 2019. The three United Patriots parties are, to varying degrees, pro-Russian and Eurosceptic – but they are also mired in internal infighting.

Croatia

Projected voter turnout

Turnout in the 2014 EP election was just 25 percent in Croatia. This year, it is likely to be more than 30 percent, largely because the current prime minister, Andrej Plenković, used to be an MEP and because Croatia will take over the EU’s rotating presidency in early 2020. There have been rumours about Plenković calling a snap parliamentary election to benefit from his current popularity. That may enable his party to govern alone, without the need to enter a coalition with smaller partners. If such an election took place at the same time as the EP vote, turnout would be even higher. This would largely benefit the ruling Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ). But it currently appears unlikely that there will be a snap election.

Main battles in 2019

The campaign is likely to focus on economic issues: how to boost Croatia’s weak growth, make better use of the EU’s structural funds, increase youth employment, and slow the emigration of Croats to other EU member states. But immigration will also be a hot issue, especially if another wave of refugees arrives at the country’s borders in the spring. Xenophobia is on the rise in Croatia: in 2017, one survey showed that 80 percent of Croats believed that “migrants and refugees should go to countries with similar culture”. If migration becomes a central topic, this will benefit the two anti-refugee parties: MOST and Human Shield. The ruling party used to flirt with far-right ideology but Plenković has positioned it as an ally of German Chancellor Angela Merkel, with a much softer stance on migration.

The mainstream

The ruling centre-right HDZ party (a member of the European People’s Party) dominates Croatia’s political landscape and could secure around 35-40 percent of the vote, giving it five or six MEP seats. The other parties of the country’s mainstream include the Social Democratic Party of Croatia (the SDP, a member of the Socialists and Democrats). It has, however, lost a considerable number of supporters in recent years due to internal infighting. It is projected to obtain around 15-20 percent of the vote and three MEP seats. Both parties – as well as the liberal GLAS/IDS (a member of the EP’s liberal group), which is projected to gain a vote share of 5-10 percent and one MEP seat – are pro-European: in favour of ever closer union, trade liberalisation, and a focus on European values.

The Eurosceptics

The decline of the SDP in recent years has provided space for new parties, such as the centre-right MOST and the anti-EU Human Shield. The latter is rising in the polls, largely due to its anti-migration discourse, which finds fertile ground in Croatia’s growing xenophobia. Human Shield is not just Eurosceptic but also anti-establishment, pro-Russian, and critical of NATO and of integration with the West. Its members do not conceal their close links to Moscow nor contact with former US presidential campaign adviser Steve Bannon and the Movement. If Human Shield enters the EP in 2019, this will provide a strong boost to the party’s popularity at home.

Cyprus

Projected voter turnout

Despite compulsory voting, turnout at EP elections has been in rapid decline in Cyprus: from 72 percent in 2004 to 44 percent in 2014. Local problems dominate the public debate, notably reunification and the current crisis with Turkey over hydrocarbon exploration. Still, Brexit and the refugee crisis (which have major implications for neighbouring Greece and Turkey) have led many Cypriots to realise how dependent on EU membership their country has become. This may herald a similar or slightly higher turnout than in the last vote. The country’s emerging far-right party, the National Popular Front (ELAM), is projected to mobilise its supporters to try to seize one of Cyprus’s six MEP seats. This should prompt other parties to urge their supporters to vote.

Main battles in 2019

Turkey-EU relations will dominate the campaigns of each major political party in the 2019 EP election. Other topics that should also feature include economic growth and employment, security and defence, and human rights. Immigration will be discussed, but it is not a central issue given that Cyprus (an island outside the Schengen Area) hosts few refugees in comparison to other European countries. The upcoming election will largely be about the race for the sixth MEP seat, which may fall to the country’s far right for the first time.

The mainstream

The three main parties in Cyprus – Democratic Rally (DISY), the Progressive Party of Working People (AKEL), and the Democratic Party (DIKO) – are projected to get two, two, and one MEPs respectively. DISY (a member of the European People’s Party) is Cyprus’s main party and dominates the centre-right of the political spectrum. AKEL (a member of European United Left–Nordic Green Left group) and DIKO (a member of the Socialists and Democrats) dominate the left and centre respectively. AKEL criticises the EU’s “neoliberal” orientation but is not opposed to the EU as such. Another left-wing party, the Movement for Social Democracy (EDEK) – which distinguishes itself from the other mainstream parties due to its opposition to a federal solution to the Cyprus problem – will compete with ELAM for the country’s sixth MEP seat.

The Eurosceptics

The ultranationalist, Eurosceptic ELAM, which is affiliated with Greece’s Golden Dawn, stands a real chance of getting one MEP seat. Currently, the party polls in fourth place, with the support of six percent of voters. ELAM opposes European integration and advocates a Europe of nations instead. More worryingly, however, it also promotes Greek nationalism and exhibits neo-fascist leanings. In 2010, the party organised a march against Turkish Cypriots and migrants.

Czech Republic

Projected voter turnout

Turnout in EP elections in the Czech Republic is regularly among the three lowest in the EU. This year, it is widely expected to be little more than 20 percent, and only slightly higher than in 2014. Migration issues might have a mobilising effect on the electorate. But, at the same time, voters may already be tired of going to the polls: in 2018, they have had to vote in presidential, senatorial, and local elections. Low turnout usually favours pro-European parties, whose supporters are relatively interested in European issues. It may also enable smaller parties (such as the pro-European centre-right TOP 09 party, which is currently polling below the threshold to enter parliament) to vie for a seat if they invest in the campaign.

Main battles in 2019

A strong Eurosceptic element will feature in the 2019 EP election in the Czech Republic due to the presence of the far-right Freedom and Direct Democracy party in the Czech parliament, and an overall rise in anti-refugee sentiment across the country. Migration will become the most controversial issue in the campaign, perhaps leading politicians to link it to security and the fight against terrorism. Other topics that Eurosceptics are likely to raise include the country’s accession to the eurozone as well as “Czechxit”. Still, ANO 2011, the party of Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, should be the clear winner of the election (despite allegations of corruption against the prime minister). It is expected to campaign on a pro-European ticket, especially given recent signs of cooperation between Babiš and French President Emmanuel Macron.

The mainstream

The pro-European mainstream in the Czech Republic is currently dominated by ANO 2011 (a member of the EP Liberal group), which may win twice as many votes in 2019 as any other party and obtain nine MEP seats as a result. Babiš won the 2018 general election with promises to stand up to Brussels and fight illegal migration. But he has softened his stance since, favouring the principle of free movement while seeking stronger controls on the EU’s border. Two established parties of the Czech pro-European mainstream – the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats – may win just one MEP seat each. The pro-European Czech Pirate Party (a member of the Greens in the EP) should finish in second or third place, winning three or four MEP seats.

The Eurosceptics

Various degrees of Euroscepticism are evident on the Czech political scene. On the far right, Tomio Okamura’s Freedom and Direct Democracy party will likely campaign against migration, eurozone accession, and Czech EU membership in general. Supported by 8-9 percent of voters, it is projected to gain one or two MEP seats. Interestingly, similar messages (and an analogous pro-Russian orientation) will feature in the campaign of the far-left Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia, which may win one MEP seats. These two radical parties aside, the conservative Civic Democratic Party (a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists in the EP) will call for a return of competencies to member states and for the Czech Republic to obtain opt-outs from the EU’s common asylum policy and eurozone accession. Currently polling second, it should win four MEP seats. Still, the party might shift closer to the European mainstream if, after the 2019 election, it joins the European People’s Party.

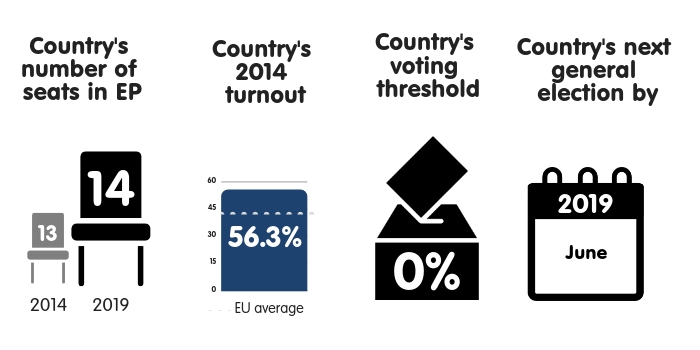

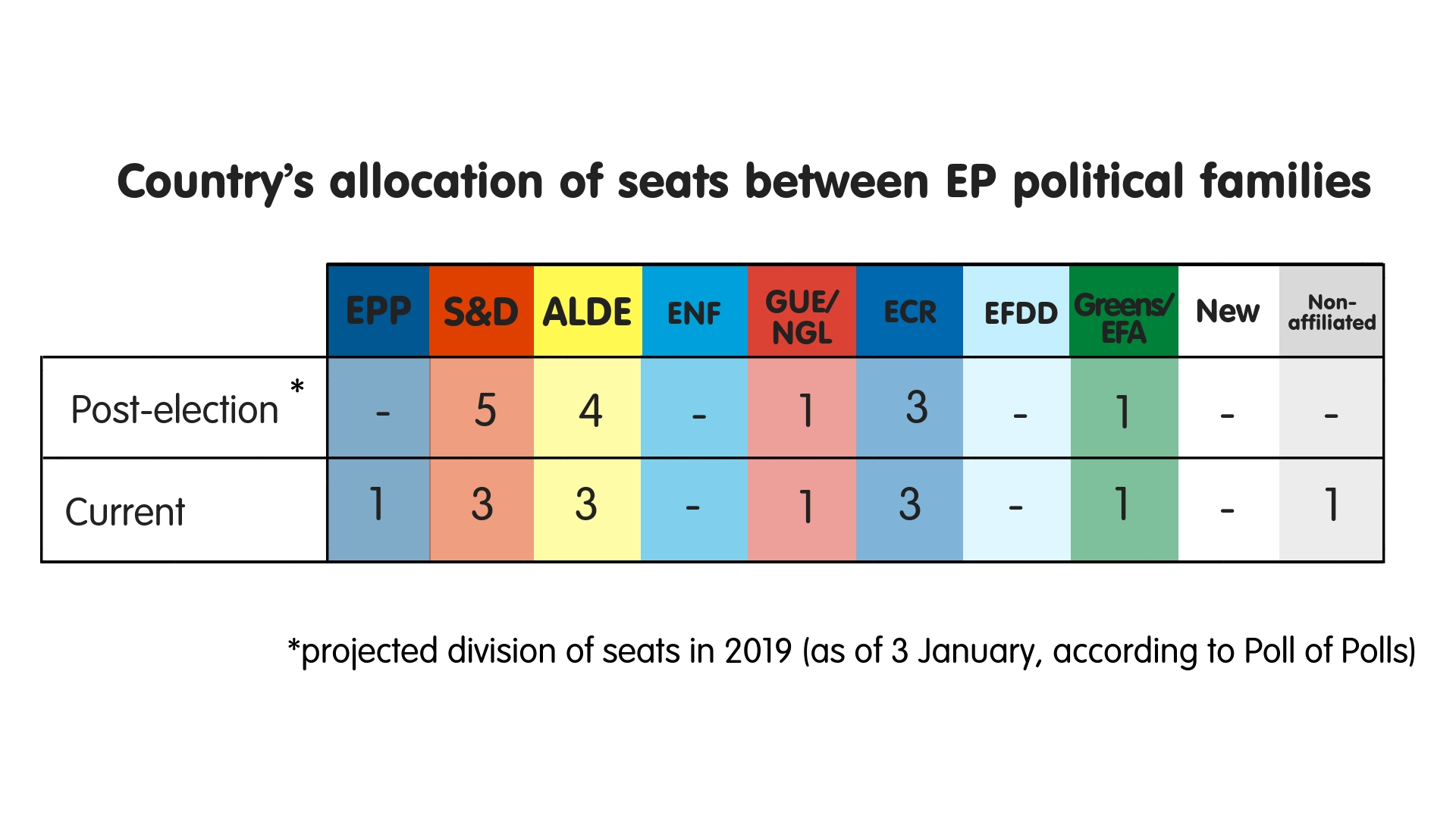

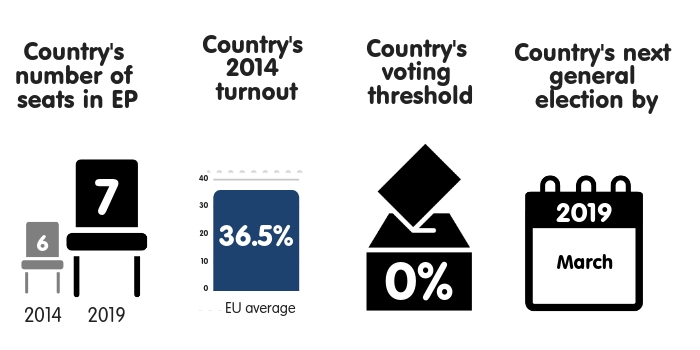

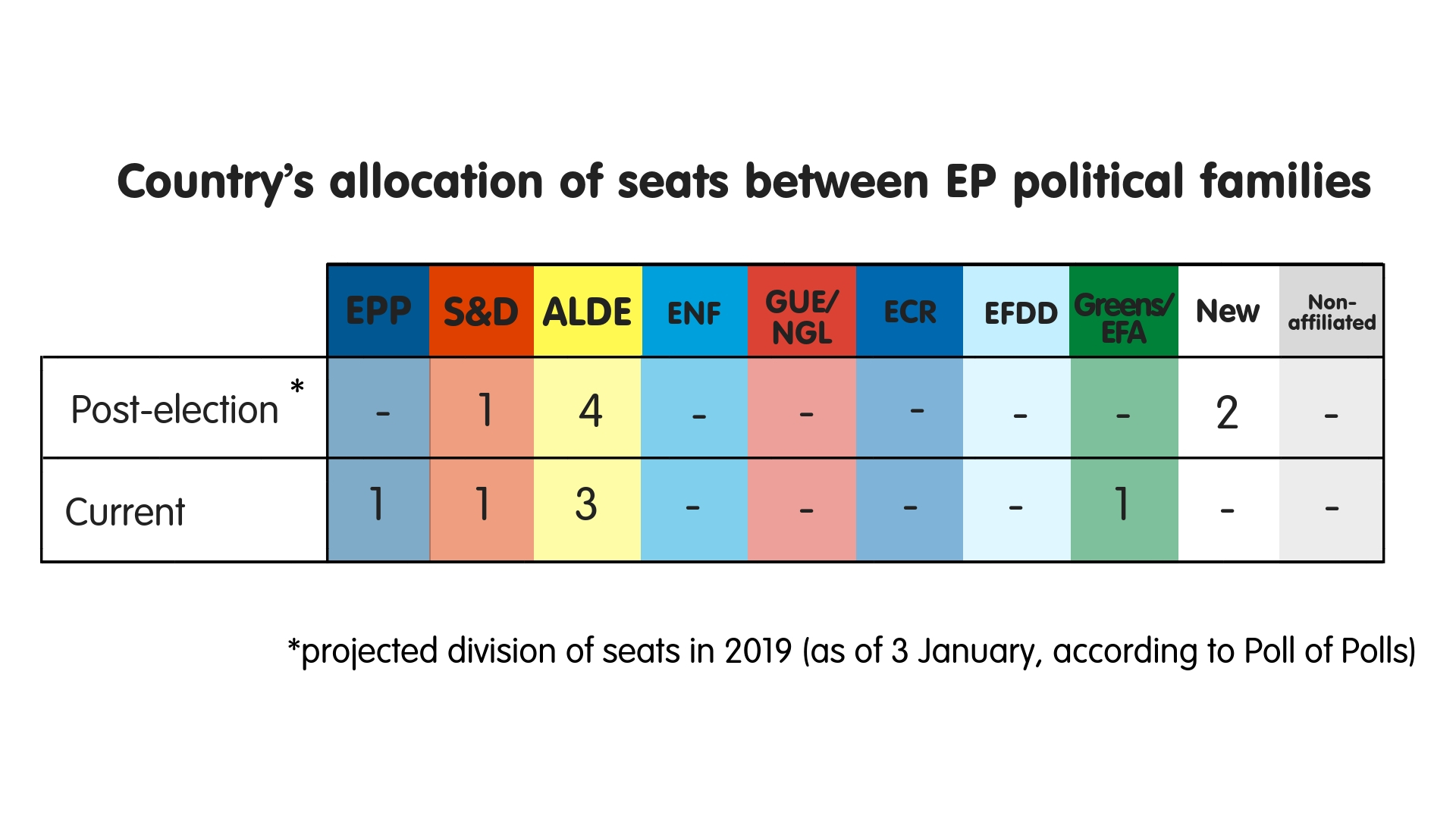

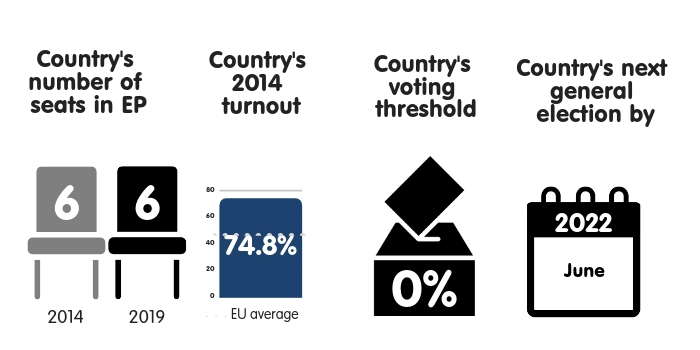

Denmark

Projected voter turnout