Eyes tight shut: European attitudes towards nuclear deterrence

Europeans remain unwilling to renew their thinking on nuclear deterrence, despite growing strategic instability. Their stated goal of “strategic autonomy” will remain an empty phrase until they engage seriously on this matter

Summary

- Europeans remain unwilling to renew their thinking on nuclear deterrence, despite growing strategic instability. Their stated goal of “strategic autonomy” will remain an empty phrase until they engage seriously on this matter.

- This intellectual under-investment looks set to continue despite: a revived debate “German bomb” debate; a new Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons; and the collapse of the INF treaty.

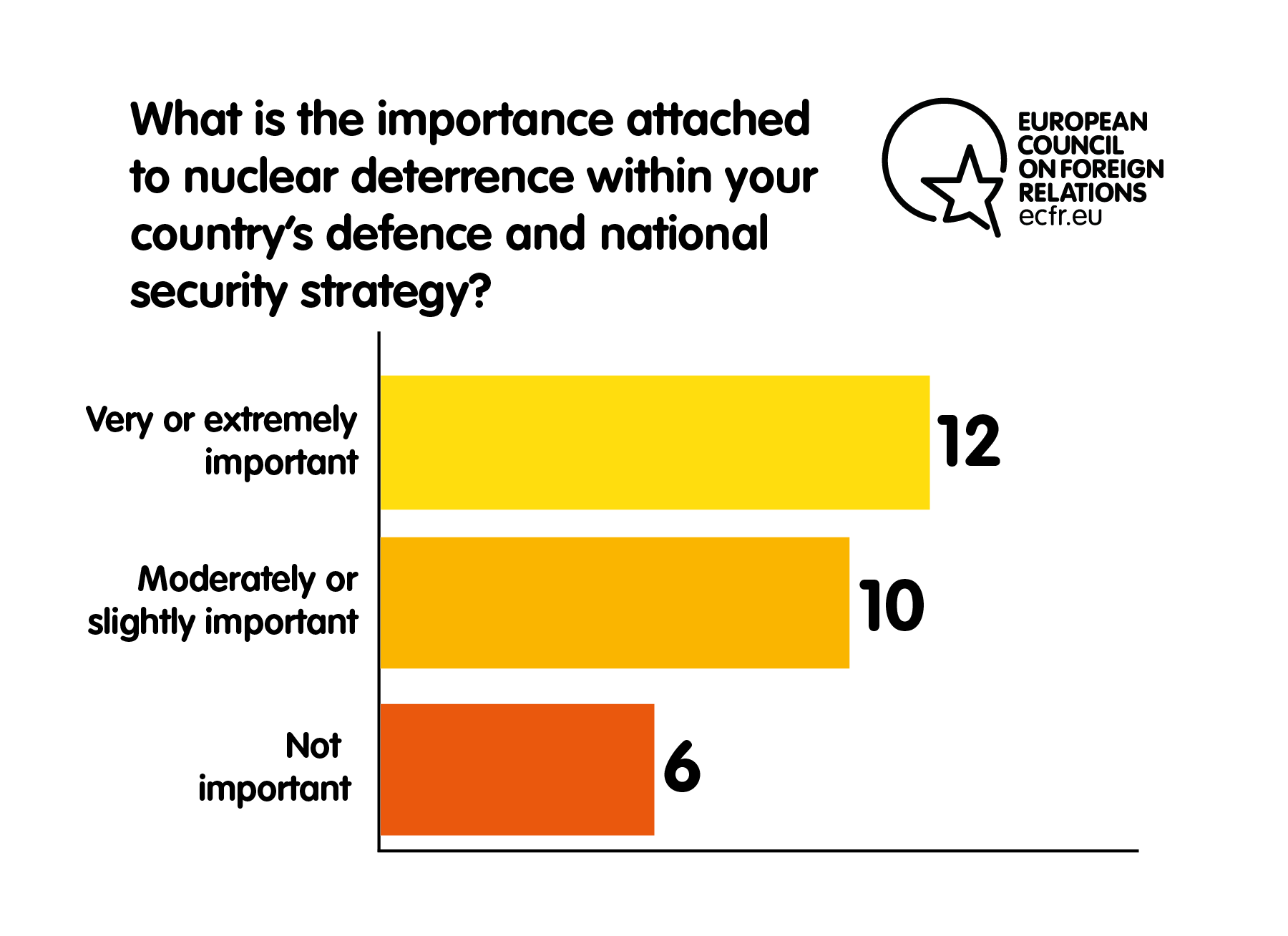

- Attitudes to nuclear deterrence differ radically from country to country – something which any new engagement on the nuclear dimension will have to contend with. And, while many governments and their voting publics are aligned in attitudes, in some crucial players like Germany the government and public are at loggerheads.

- No European initiative to declare strategic nuclear autonomy is yet practicable but a strategy to hedge for future uncertainties is available.

- As a first step, the UK and France should convert the idea of a European deterrent from mere notion into credible offer, by thickening their bilateral nuclear cooperation and sending growing signals that indicate their readiness to protect others.

Introduction

The 29 July edition of Germany’s Welt am Sonntag hit newsstands like a bombshell. The weapon in question was painted in German national colours, and illustrated the front-page headline “Do we need the bomb?” Inside, the writer argued that: “For the first time since 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany is no longer under the US nuclear umbrella.”[1]

It is extraordinary that this question should arise so prominently in peace-loving, anti-nuclear Germany. But it is not before time. This year, the European Council on Foreign Relations conducted a comprehensive survey of attitudes towards nuclear issues across the member states of the European Union. Two overarching themes emerged. Firstly, despite the growing insecurity all around them, Europeans remain unwilling to face up to the renewed relevance that nuclear deterrence ought to have in their strategic thinking. Secondly, and as a consequence, national attitudes remain much where they were when the subject dropped off the agenda at the end of the cold war – which is to say, scattered across the entire spectrum from those who continue to see nuclear deterrence as an essential underpinning of European security to enduring advocates of unilateral nuclear disarmament.

This is hardly the only important challenge on which Europeans’ views are all over the place, and about which they would prefer to remain in denial. As one official told the authors, “Europe has not only outsourced its security, but also its security thinking”. But when set against the dramatic changes occurring in the international security environment, the results of this research demonstrate that there is now an urgent need for Europeans to think about, and debate, nuclear deterrence anew. A ‘German bomb’ is unlikely to prove attractive – not least to Germans themselves. Europeans must instead give serious consideration to whether a Franco-British ‘nuclear umbrella’ would be a possible and desirable complement to, or substitute for, the current US nuclear guarantee to Europe. This paper concludes that this issue is significant but belongs to a range of nuclear weapons-related topics with which Europeans need to re-engage.

Regardless of whether it proves viable to agree to a “nuclear Saint-Malo”, to borrow a phrase coined by a member of ECFR’s pan-European research team, one thing is clear: the situation is such that Europeans can no longer pretend that their declared ambition of “strategic autonomy” is more than an empty phrase unless they engage seriously on the nuclear dimension. The absence of a European deterrent may be a fatal flaw for such an ambition. Besides nuclear capabilities, there are many ways in which Europe can move towards its stated bid for strategic autonomy. But, without this, many Europeans will continue to believe that Russia will always hold the whip hand in any military confrontation with a Europe not backed by a credible US nuclear guarantee. And yet most Europeans’ approach to the nuclear dimension of a rapidly shifting strategic environment is to keep their eyes tight shut.

Darkening skies

Europeans are, of course, aware that their security environment is deteriorating. They know that the neighbourhood they once aspired to turn into a ring of friends has instead turned into something closer to a ring of fire. They know too that this violence has ventured into European territory in the form of terrorism. But Vladimir Putin’s Russia has also played a key role in European perceptions, as evidenced by the coincidence between the rise in European defence budgets and the war in eastern Ukraine that began following Russia’s annexation of Crimea. And with Donald Trump resident in the White House, doubts have risen about the United States’ commitment to Europe’s security, including through NATO.

The 2016 Global Strategy set strategic autonomy as the centrepiece ambition for the EU and its member states.[2] Though ill-defined, this concept nonetheless indicated that Europeans acknowledged the need to be readier to fend for themselves and, consequently, to do more on defence by standing on their own feet and reducing their dependence on the US. But the truth is that NATO and the accompanying US security guarantee were, and remain, the defining security frame for Europeans. The progress made towards a European Defence Union since 2016 has addressed only conventional capabilities and Europe’s defence technological and industrial base. In all these discussions and developments, European governments were all too happy to ignore nuclear issues almost entirely.

And yet the nuclear dimension of this security environment is obvious. A recent concerted diplomatic effort led to the adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) at the United Nations in 2017. But this effort won no support from any of the current nuclear weapons states – whether those recognised by the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) or the others. On the contrary, nuclear weapons have since gained further salience in Russia’s defence strategy, while the US has moved to a more “flexible” policy under its 2018 Nuclear Posture Review and its inclusion of low-yield warheads.[3]

At the same time, events in east Asia and the Middle East have increased worries about a rise in the number of nuclear states; and the risk of proliferation crises in Iran and North Korea has dominated the headlines at various times in the last year. The situation in both regions remains highly unpredictable. Europe is more or less absent from efforts to solve the situation in east Asia. And, although it is playing a crucial role in trying to keep the Iran nuclear deal alive, it faces a formidable challenge due to the US not only exiting the deal but also trying to prevent Europe from implementing its own non-proliferation strategy by threatening secondary sanctions on European companies.

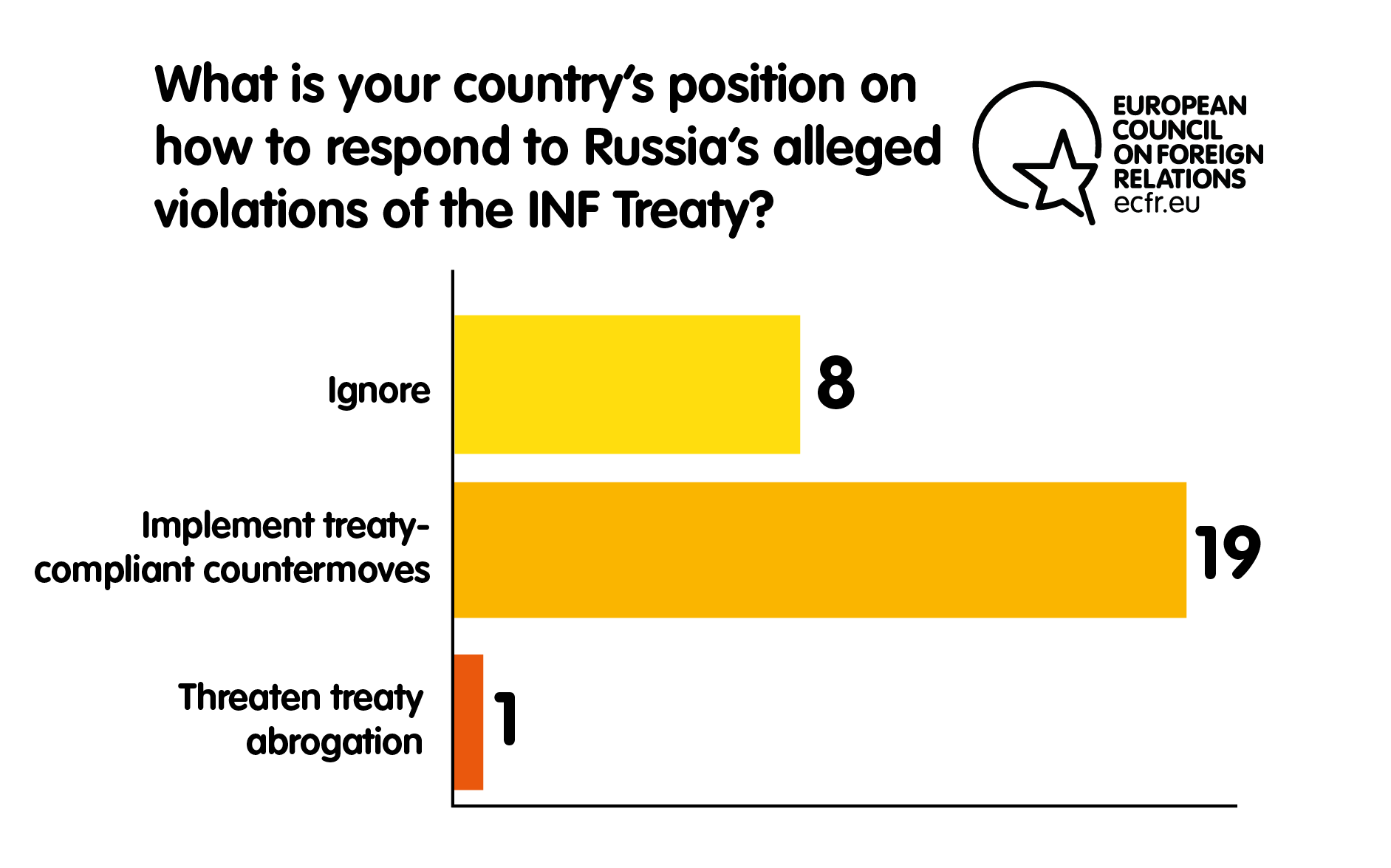

In Europe itself, the crisis in Ukraine has given way to Russian nuclear sabre-rattling – through not just rhetoric but also the deployment of short-range nuclear-capable missiles to the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, which borders two EU member states. This has further weakened a European security order to which the US and Russia have, in fact, been actively making changes for nearly two decades; the notion of an unchanging post-cold war order does not bear too much scrutiny. The US unilaterally terminated the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002, while Russia has likely violated the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) by testing and deploying the SSC-8, a new and prohibited intermediate-range, nuclear-capable missile. Both powers have announced new plans to strengthen their strategic arsenals. Yet, although NATO statements have raised this issue, Europe scarcely seemed to act upon it until the US announced its intent to withdraw from the INF treaty.[4] When Russia deployed a new missile, the SS-20, in the cold war, the result was the Euromissile crisis. In contrast, Europeans have chosen to react to the appearance of the SSC-8 by looking the other way.

Trump has shown that he meant it when he described NATO as obsolete, even though Europeans are only slowly coming to terms with this fact. But even in the post-Trump era to come, the US may well fold up its nuclear umbrella.[5] For the moment, European governments continue to believe, or hope, that they can go on taking advantage of the comfort blanket of the post-cold war order. This is partly because they have fallen so far out of practice of discussing nuclear weapons issues with one another, not to mention with the public.

Of course, memories of the Euromissile protests of 35 years ago result in some governments turning a blind eye. Others really are wary of Russia. Some governments have begun to recognise the changing environment formally: for instance, the French armed forces ministry’s recent strategic review noted the emergence of a “nuclear multipolarity”, the growing risks associated with the “deconstruction of the security architecture in Europe”, and the strategic “unpredictability and ambiguity” that come with it.[6] But most European leaders still shy away from opening up what they fear could be a Pandora’s box of difficult questions and possible political opposition.

Silence above, ignorance below

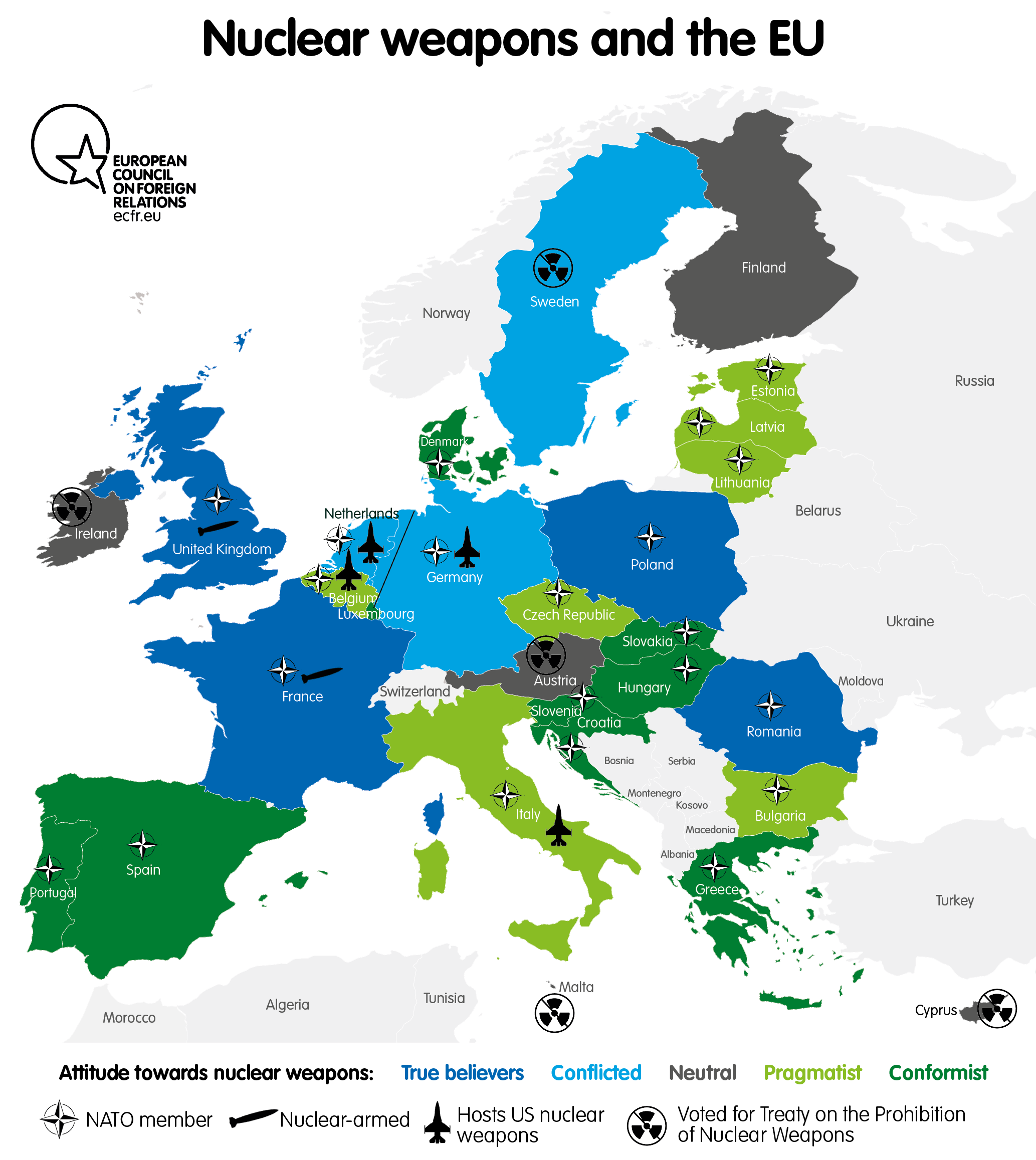

European attitudes are a patchwork of opinions: the United Kingdom and France are nuclear powers in their own right, with public opinion more or less solidly behind this status. The historical experience of Poland and the Czech Republic leads these states to be more confidently supportive of nuclear deterrence. Countries such as Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany have seen civil society clash with their governments’ decisions around hosting nuclear weapons. Ireland and Austria are active campaigners for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

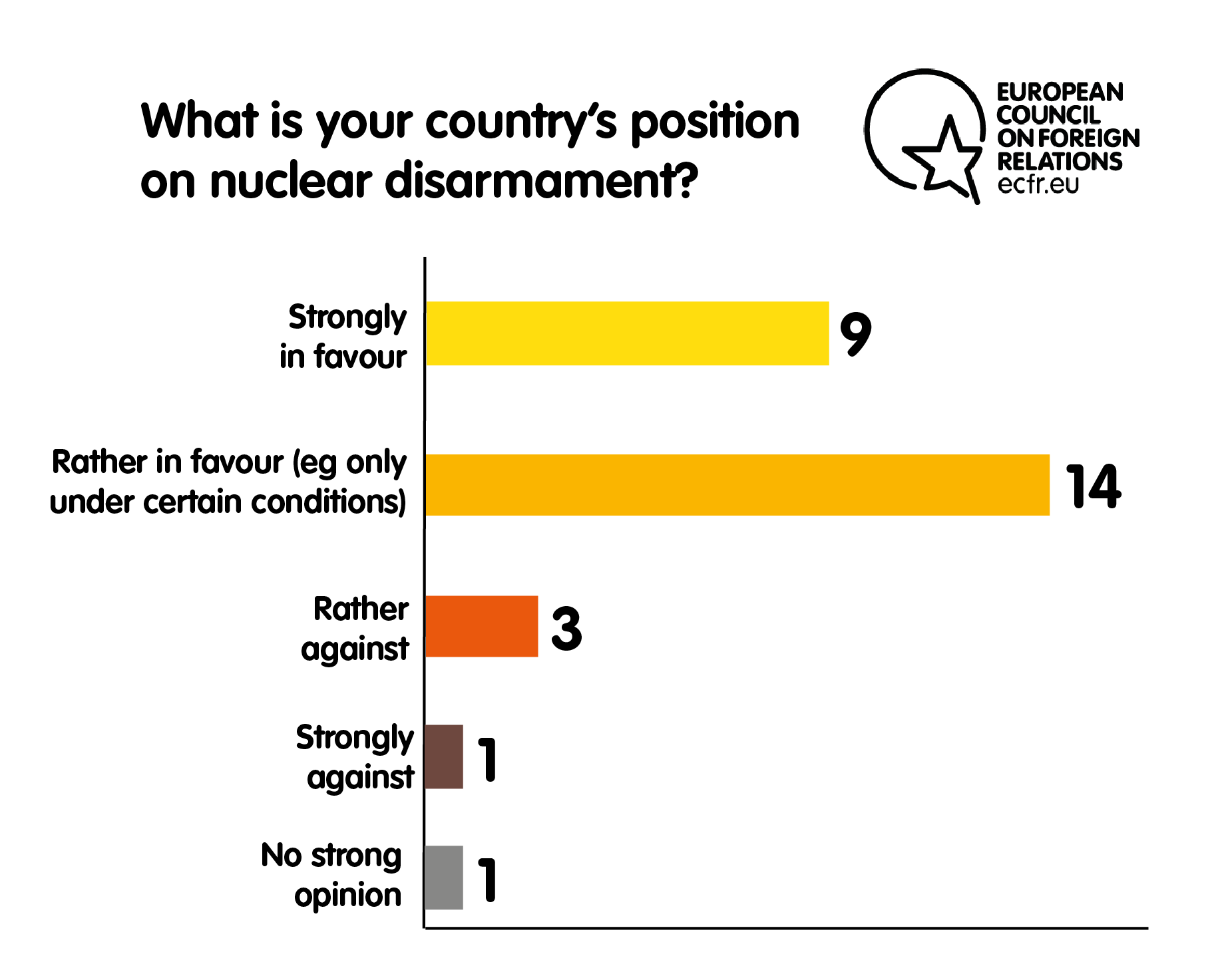

Despite all this, most EU member states have two things in common in this matter. First, nearly all of them share an official, if ostensible, commitment to reducing nuclear weapons: research for this paper revealed that only three member states harbour reservations about the goal of nuclear disarmament. This is all while many of these countries remain within NATO, which is of course underpinned by the potential of nuclear-backed intervention via Article 5. The potential tension between this pro-disarmament stance and the enjoyment of the US nuclear umbrella is something yet to fully play out.

Second, nuclear weapons have little salience in the public imagination. On the occasions in the late cold war period when European governments were obliged to make difficult decisions about nuclear weapons, these became fraught and contested in the country at large as well as in parliament. But with the disappearance of the Soviet threat, Western governments and populations became less obliged to think, and argue, about nuclear weapons with the degree of heat and rigour that they had had to prior to 1989. In Europe, most were more than content to enjoy the happier and more hopeful international environment, and to simply dismiss nuclear worries from their minds. Rather than peace underpinned by nuclear weapons, as many cold war leaders characterised it, Europeans began to enjoy peace with nuclear weapons still around. Nuclear weapons disappeared from the public debate. The end of the cold war led to an effort to reduce the total number of nuclear warheads in the world, with Russia and the US doing substantially more heavy lifting in this regard even if they still possess considerably more weaponsthan France and the UK, which have both moved significantly towards minimal deterrence.

If anything, the public today is rather inclined towards disarmament – which may partly explain its relative lack of concern as the total number of weapons in the world fell, although it is hard to say that Russia and the US won many plaudits for their efforts either. If a shift in public attitudes does now come about, this may emanate from high-level activism. In the context of the TPNW, the decision to award the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons hints at a new wave of abolitionism. This also finds stronger expression in national politics: last year’s German federal election saw the Social Democrat challenger for chancellor promise the removal of US nuclear weapons from the country. And, in the UK, a unilateralist disarmer is now leader of the Labour Party and Scotland’s ruling Scottish National Party is firmly opposed to nuclear weapons.

The current fraught and unstable international environment has not led the wider public to fret about nuclear issues – yet – nor for their governments to take the lead on this. The disconnect between public leanings and government policies appears to have induced governments to keep discussion of nuclear matters low key. If this is the case, it seems to have worked. But Europe probably has the ingredients for popular opposition to nuclear deployments to emerge once again.

Europe’s nuclear families: cousins and rivals

To understand the situation better, ECFR’s network of 28 associate researchers carried out investigations into European attitudes towards nuclear weapons. These comprised interviews with more than 100 policymakers and analysts, and research into policy documents, academic discourse, media analysis, and opinion polls. The research questions centred on what countries today think of nuclear deterrence, how they assess nuclear threats to their own security, and what action they are considering in response. The data reflects what officials and experts believe to be the position of their respective countries on these topics. The country-by-country analyses are contained in the annex.

Perhaps the most striking finding of the survey concerns the immutability of attitudes across Europe. Most, if not all, European countries see recent events as proving their traditional attitudes right. They conclude that, despite the changed environment, there is little need for further reconsideration of their position on nuclear matters. This, therefore, provides little impetus for governments to break their silence and dispel public ignorance.

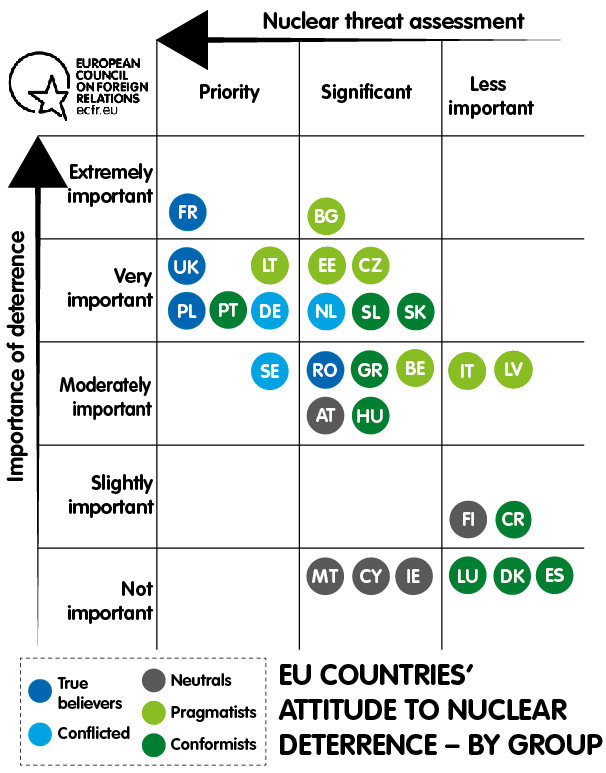

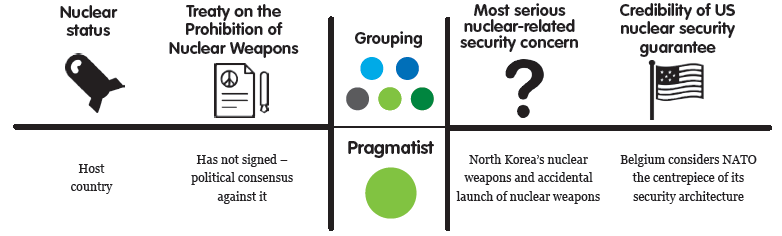

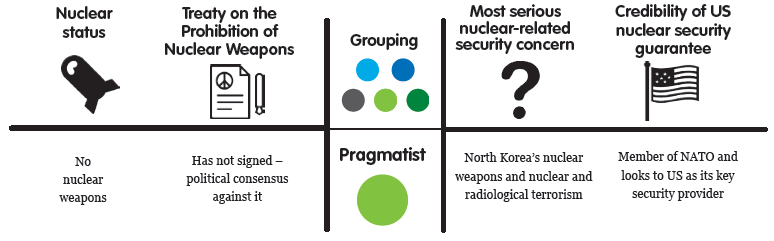

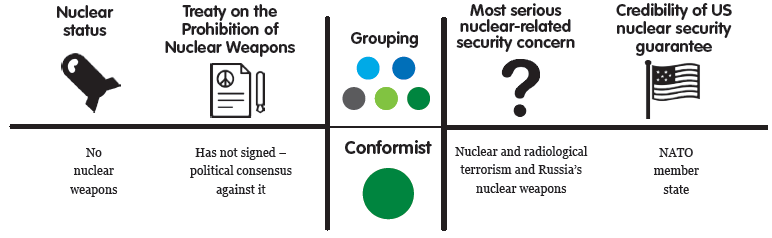

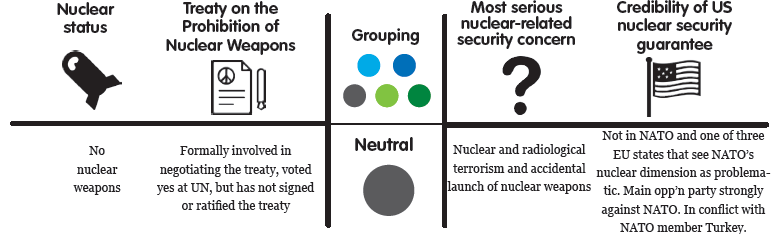

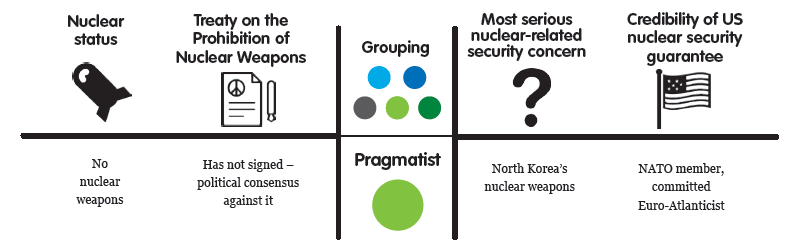

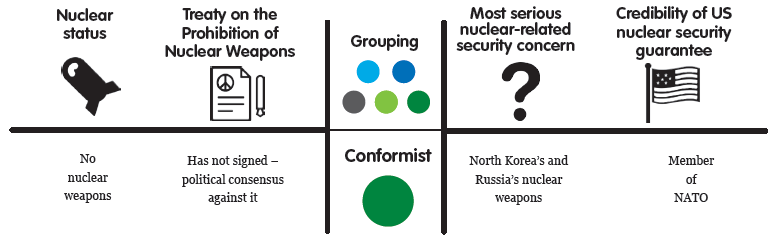

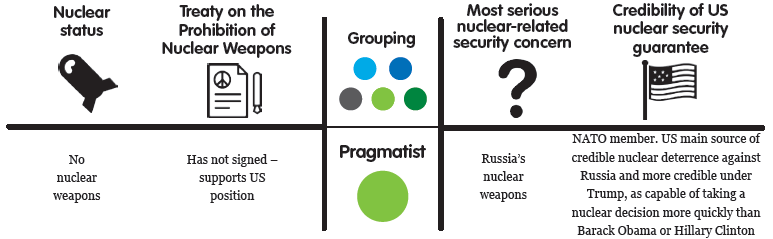

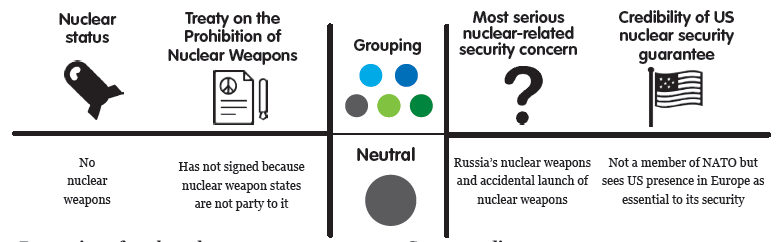

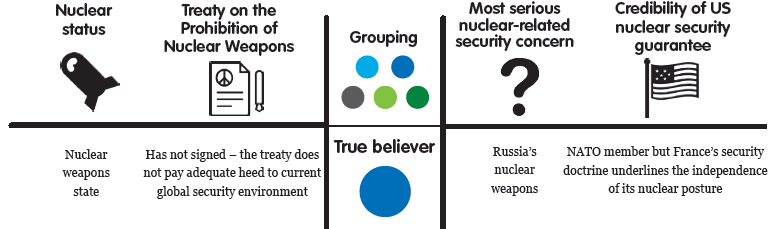

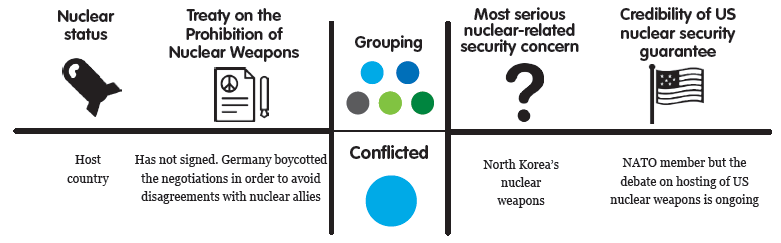

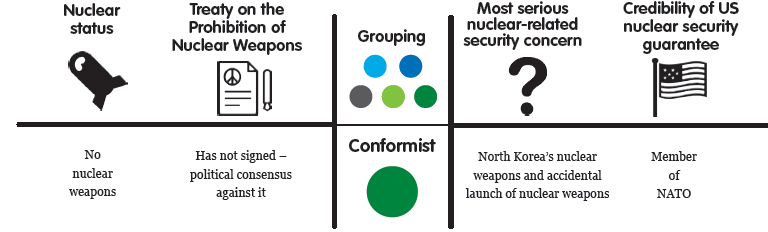

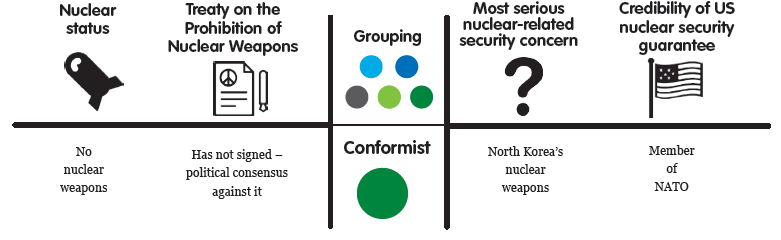

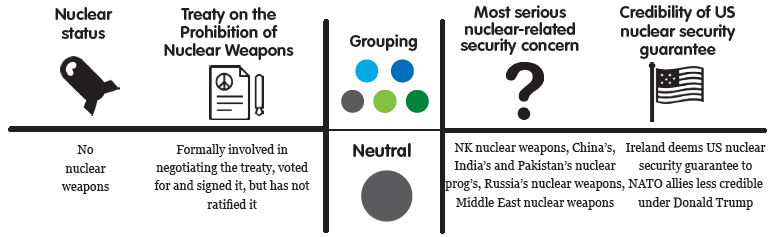

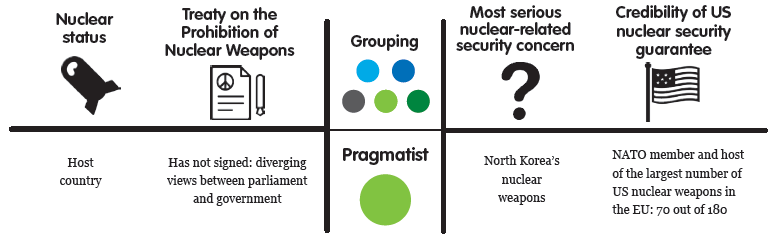

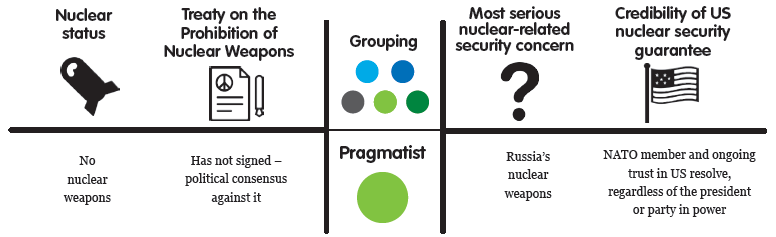

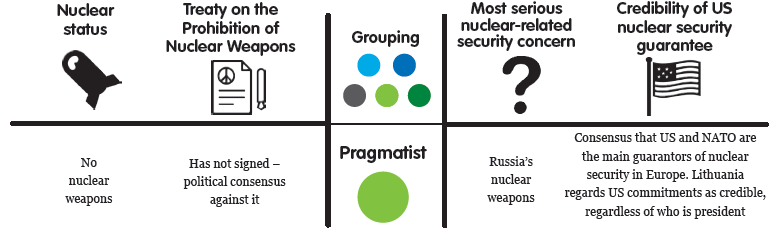

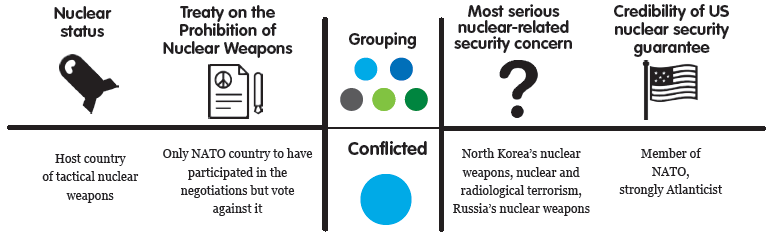

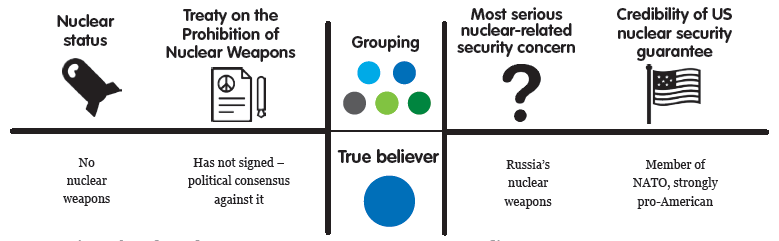

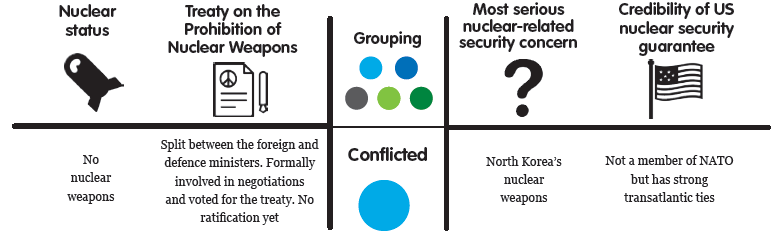

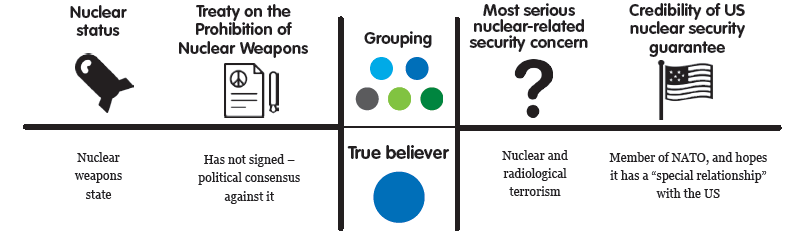

EU member states continue to span the full spectrum from committed nuclear powers to determined abolitionists – and they fall into five groups depending on their attitude to nuclear deterrence: True Believers, Neutrals, Conflicted, Pragmatists, and Conformists.

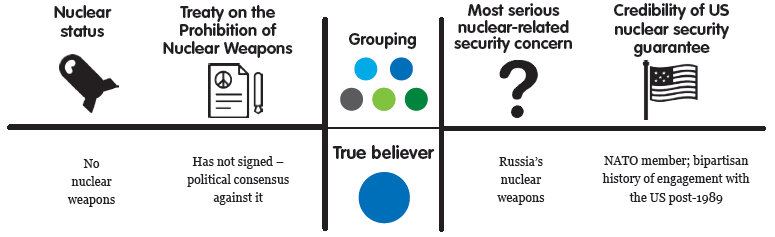

At one end of the spectrum lie the True Believers: France and the UK, accompanied by Poland and Romania. The first two are nuclear weapons states, and plan to stay that way: even with an avowed unilateral disarmer leading the opposition, most Labour members of parliament backed the renewal of Trident in a 2016 vote. Since the end of the cold war, France and the UK have modernised their nuclear arsenals while also pursuing reductions in their size under doctrines of minimum deterrence. Each has also limited where its weapons are deployed.

Poland and Romania also belong to the True Believers camp because they are greatly preoccupied with Russia and are active in seeking out reassurance from the US and even increased physical presence on their soil from the superpower. Both countries host a rotating brigade and elements of NATO’s missile defence system, and Poland recently offered to pay for a new US base – “Fort Trump” – as part of a bilateral arrangement. That said, these countries’ commitment to nuclear deterrence does not involve hosting US nuclear weapons on their territory.

All four countries rank nuclear threats as important in their strategic assessments and have also determined that nuclear deterrence should play an important part in their defence and national security strategy. In addition, unlike others that may share this approach, such as Germany, public opinion in their countries is behind them, meaning they are not conflicted about their commitment to nuclear deterrence.

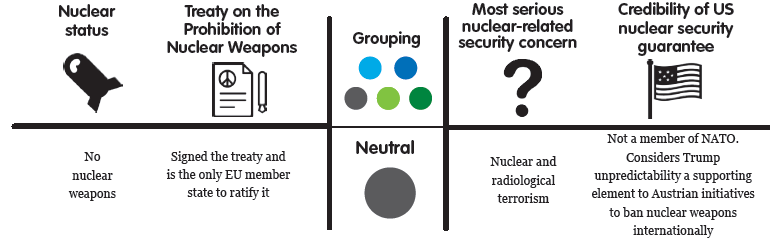

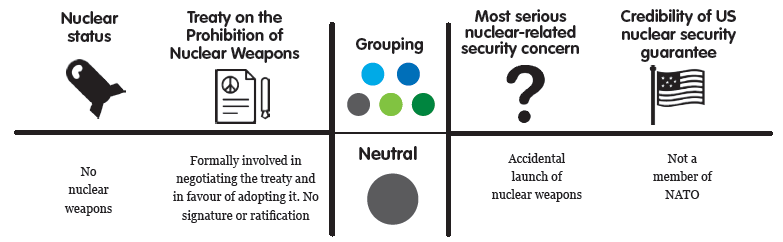

At the other end of the spectrum are the Neutrals: Ireland, Austria, Malta, Cyprus, and Finland (all non-NATO members of the EU). The first two pride themselves on their anti-nuclear tradition: over the last few years they proactively sponsored the TPNW at the UN and signed it. One of Ireland’s five stated core foreign policies is to achieve a world free of nuclear weapons in addition to promoting disarmament.[7] Austria has been even more active on this front: it ratified the TPNW in May, and it has also been a vocal and intransigent supporter of the abolitionist agenda, holding the view that only a generalised abandonment and condemnation of such weapons can halt their proliferation.[8]

Malta and Cyprus have traditions of non-alignment, as well as friendly relations with Russia. They forgo reliance on nuclear deterrence in their defence policy, and they also voted in favour of the TPNW at the UN, although they have not yet signed the treaty.[9] But they contrast with Ireland and Austria because of the activism displayed by the latter two countries.

Finland, also non-aligned, has grown closer to NATO in recent years but the nuclear threat is not a priority in its strategic assessment of its environment. Consequently, deterrence remains marginal to Finland’s defence strategy. Still, it strikes a more moderate pose than others in the Neutrals group when it comes to the abolitionist agenda: Finland did not take part in the TPNW vote and has declined to sign the treaty – determined, it seems, to avoid any position at all on nuclear issues beyond support for the NPT. To some extent, Finland could be considered in a category of its own, based on the fact that it is so resolutely self-contained.

As another historically neutral member of the EU, Sweden voted in favour of the TPNW at the UN. Yet if the Neutrals in this typology have taken their positions with minimal domestic controversy, nothing could be less true of Sweden – which, therefore, joins the Netherlands, and Germany in the Conflicted group.

In all these countries, civil society is actively organised and critical of nuclear weapons, while votes in the national parliament reflect a deeper level of controversy over the nuclear issue among the wider public. In Sweden’s case, growing worries about Russia and increasing defence cooperation with the US and NATO have clashed with its cherished ‘peace’ tradition. This has led to open splits within the government over its signing of the TPNW, and to the creation of a special commission to review the arguments for and against acceding to the treaty.

Similar tensions caused the Netherlands to break NATO ranks by engaging in the TPNW negotiations, under pressure from the Dutch parliament – only to then vote against the treaty. There are further difficulties ahead for the Netherlands as it will soon need to replace its fleet of F16s (see box). In 2012 its parliament voted that the replacement aircraft should not be nuclear-capable, putting in doubt The Hague’s ability to continue to be part of NATO’s nuclear-sharing arrangements.[10]

Meanwhile, in Germany, the public has long been overwhelmingly hostile to NATO’s nuclear policy, but German governments have traditionally supported it. Despite its familiarity with this tension, Germany’s upcoming decision on a dual-capable Tornado replacement will not be straightforward. This is all the more true now that key figures in government, including the chancellor, are challenging the traditional exclusive dependency on the US strategic umbrella.

Tough decisions ahead: Nuclear burden-sharing and dual-capable aircraft renewal

Four European countries keep US free-fall nuclear bombs on their territory, for delivery by their own aircraft: Belgium, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands. This long-established arrangement is part of NATO’s doctrine of ‘nuclear burden-sharing’ – the idea that nuclear risks and responsibilities should be shared, to demonstrate alliance solidarity and to make the alliance’s deterrent threat more credible.

The dual-capable aircraft involved in this nuclear-sharing mission all need replacement in the near to medium term. This means that Belgium and the Netherlands (which currently use F16s), and Germany and Italy (which use Tornados), will not only need to acquire new aircraft, but also to include special wiring in a proportion of the replacement national fleets to make them dual-capable – that is, able to deliver both nuclear bombs and conventional munitions.

The US is making dual-capable as well as conventional F35s for its own national purposes and is keen for European nuclear burden-sharers to buy this aircraft.

The acquisition of F35s is, in any case, a real bone of contention from the standpoint of Europe’s growing preference for fostering its own defence technological and industrial base. But the dual-capable issue is creating problems of its own. Italy and the Netherlands have already decided to procure F35s, while Belgium and Germany have not made their decision yet. But even the former pair have not publicly made known their choice concerning the ability of these aircraft to carry nuclear weapons. Among the latter, the Dutch parliament has voted against such a move.

The remaining 16 EU member states are all NATO members. They subscribe to NATO policy on nuclear deterrence, and they all followed the NATO line on the TPNW, which was to dismiss the proposed treaty as unrealistic and potentially damaging to the NPT. But these member states exhibit differing degrees of conviction, reflected in their rough segregation into two further groups.

The first of these is the Pragmatists. These are: Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Belgium, and Italy. The five central and eastern European states in this group share, to varying degrees, a matter-of-fact acceptance of the importance of the nuclear element in NATO’s strategy. This is largely due to their distrust of Russia (they have other reasons for this too). Belgium’s future as a nuclear burden-sharer is not in doubt, though it too faces a dual-capable aircraft decision that will be difficult for defence industrial and political reasons. Italy too will remain a burden-sharer as it has already opted for the F35: the advantages of positioning itself as a staunch US ally take precedence over the widespread view that Russia need not be a threat if Europe handles it properly.

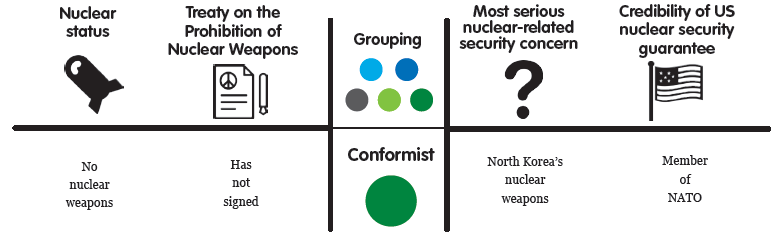

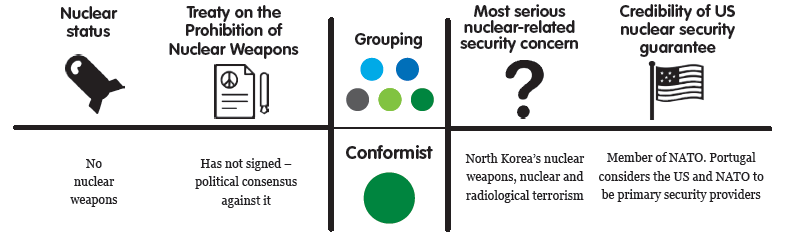

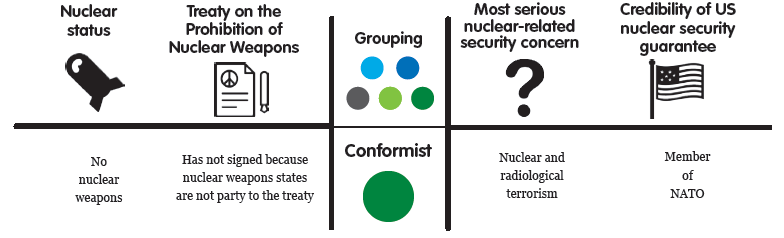

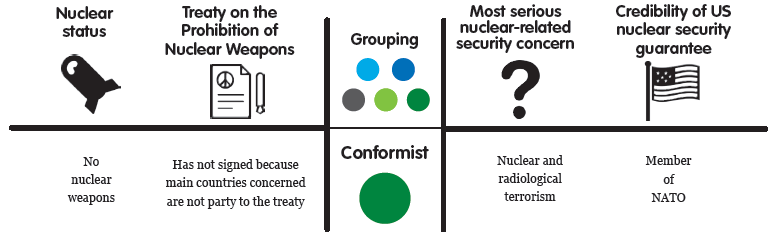

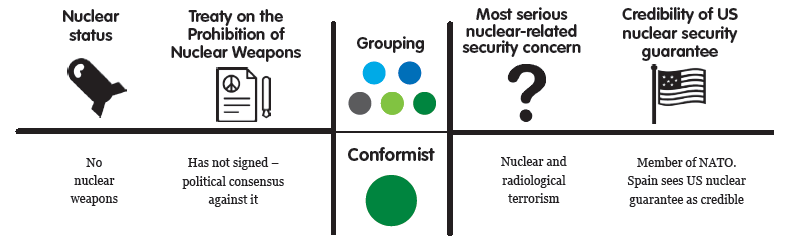

This leaves the final, and largest, group: NATO states that are less concerned with nuclear threats than some other European countries are, and that look on deterrence as of only limited importance to their defence. For them, going with the NATO flow is the easiest and most advantageous course. They are the Conformists: Croatia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Hungary, Greece, Denmark, Luxembourg, Spain, and Portugal. Each country, of course, has its own national attitudes. At one end of the spectrum, Croatia is fundamentally unconcerned about nuclear issues, but it is worried by Russian activities in the Balkans. Denmark, meanwhile, combines a traditional Nordic nuclear aversion with tough-minded Atlanticism. But all belong firmly in the mainstream of European countries that would be happy if agreed NATO language on nuclear policy was rolled over indefinitely.

Shaping the nuclear question

ECFR’s research sheds light on the issues that contribute to each country’s overall view of nuclear deterrence. All are live matters that are actively shaping opinion among both governments and the public: Russia; the reliability or otherwise of the US nuclear security guarantee; proliferation crises; nuclear disarmament; missile defence; and NATO.

Russia in Europe’s threat perception

The survey results confirm that the perception of Russia as a threat plays a significant role in influencing the nuclear stance of most EU states. It comes as no surprise that EU member states are divided on their strategic assessment of Russia. But there is a diversity of attitudes even between those that have a similar threat perception. Those that see Russia as a threat, irrespective of its nuclear power status, tend to cluster at the more hardline side of the spectrum, either as True Believers or as Pragmatists. At the other end, those that do not see Russia as a threat feature strongly among the large Conformist group. And it makes sense that those who support the abolitionist agenda come from traditionally neutral states. But there is no clear link between a country thinking Russia a threat and Russia’s possession of nuclear weapons; there are countries in all groups that agree it is a threat in this way but disagree on how to respond.

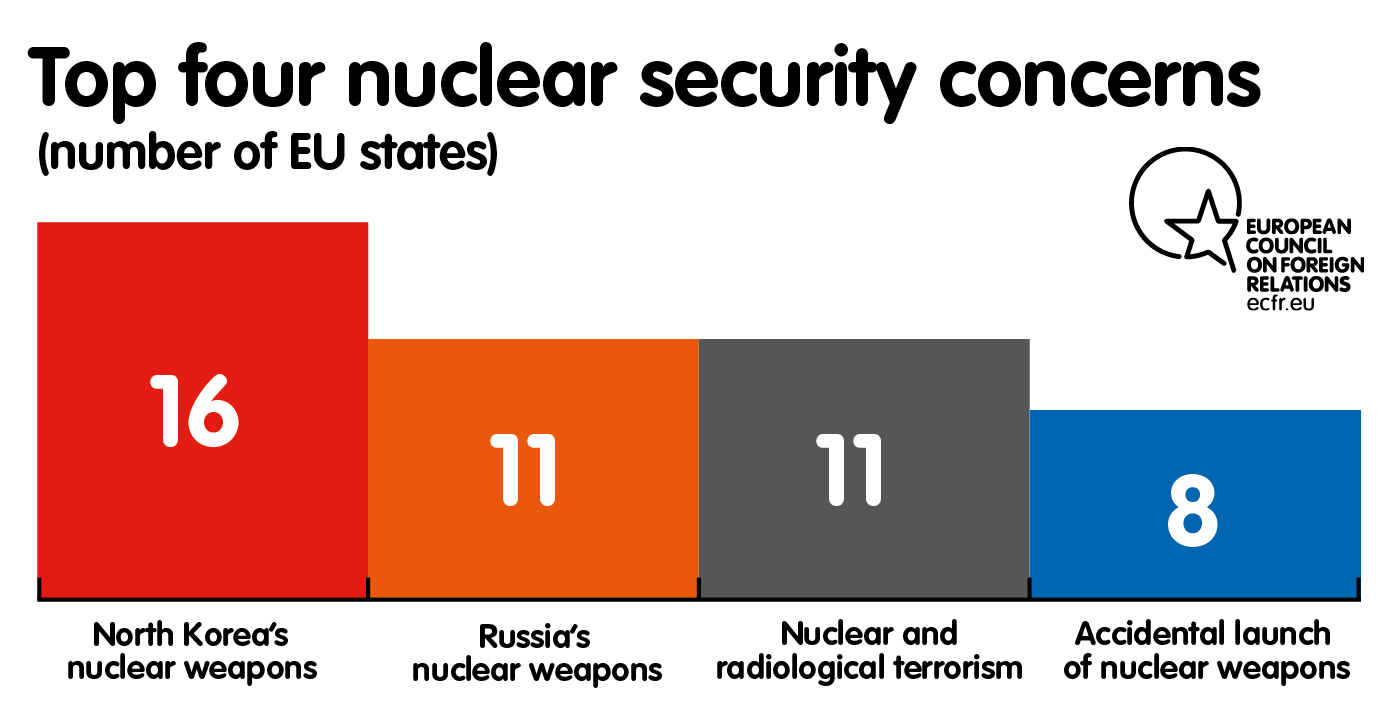

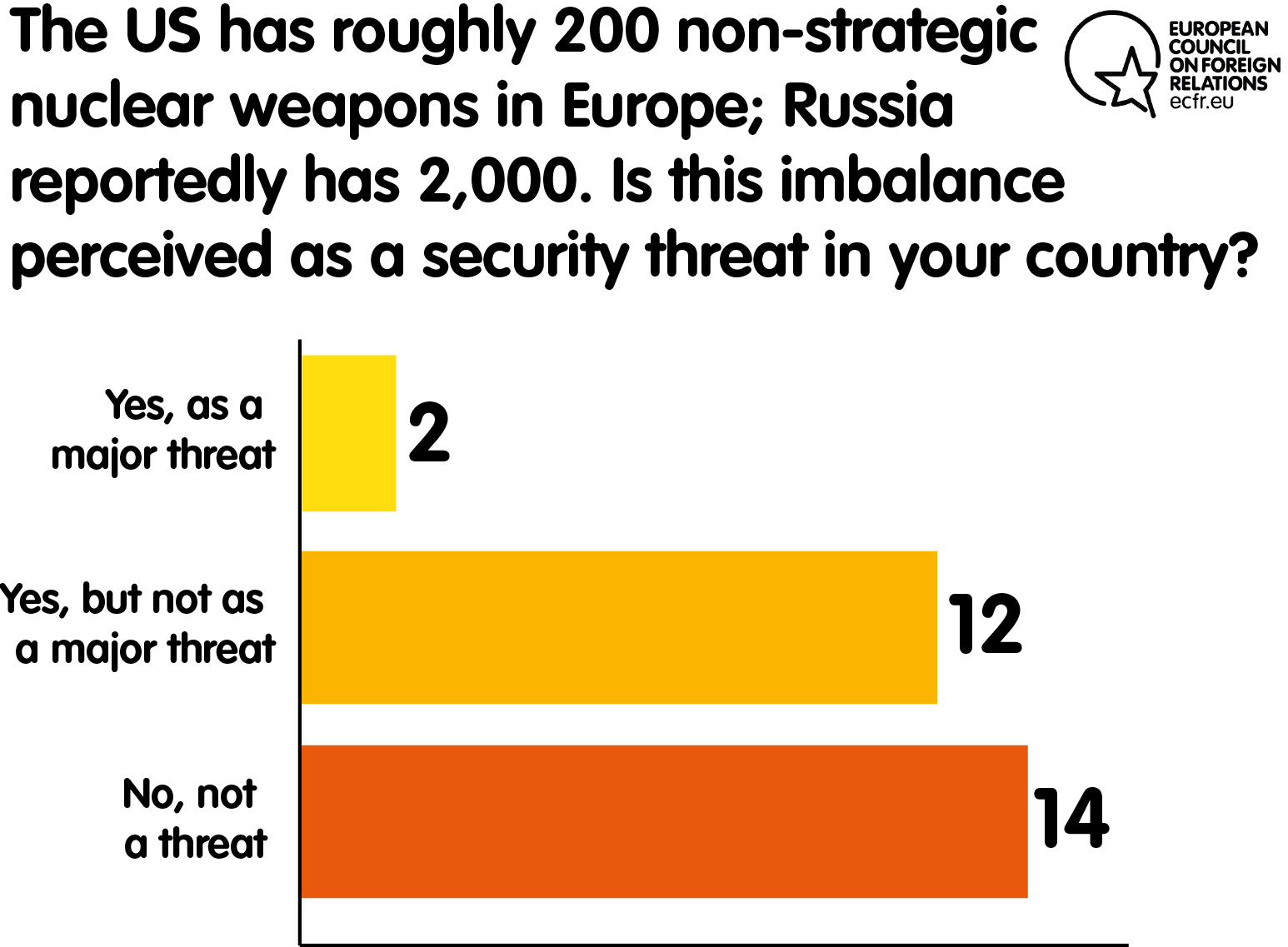

Studying member states’ views on what constitutes the greatest threats further reveals the diversity of Europeans’ attitudes and perceptions. Russia’s nuclear arsenal is the top concern of 11 member states and a leading concern of several others. Most of these member states are True Believers or Pragmatists. These same states also agree that the imbalance between the reported numbers of US non-strategic nuclear weapons – 200 – and those of Russia – 2,000 – is a threat, while half of member states do not see this as a threat at all. But, overall, most member states do not see Russia as their top concern from a nuclear threat perspective. Instead, proliferation is their main concern.

Three of the four True Believers (France, Poland, and the UK) consider nuclear threats to be a priority relative to other – conventional and non-conventional – threats. But this is also the case for other countries: Sweden considers nuclear threats a priority, which is what drives it towards its Conflicted neighbours.

Ireland and Austria, members of the Neutrals group, overlap with Estonia and Latvia – Pragmatists – in the sense that they all agree that there is a threat from Russia that is amplified by its possession of a nuclear arsenal. The difference between them resides in the fact that the former consider this to further support their case for nuclear abolition while the latter insist that NATO deterrence plans should take into account scenarios involving the use of tactical nuclear weapons by Russia. Countries that consider nuclear threats to be less important than other types of threat feature strongly among the Pragmatists and the Conformists.

Trump: not the game-changer

Trump’s arrival in the White House as the first “America First” president in decades, and certainly in the NATO era, might have increased European insecurities to the point of prompting Europeans to consider shouldering more responsibility for their own defence – and consider too that doing so might include a nuclear dimension. This has found a voice in some quarters: key US allies have raised the issue publicly since Trump’s election. In 2017 in Poland, Jaroslaw Kaczynski expressed support for the idea of a European nuclear power, only to lament that he did not think it would happen.[11] The year before, Bundestag member Roderich Kiesewetter remarked: “if the United States no longer wants to provide this guarantee, Europe still needs nuclear protection for deterrent purposes”. He also raised the notion of a Franco-British nuclear umbrella for Europe financed through a joint European military budget.[12] The Bundestag subsequently commissioned a review that determined that Germany could legally finance the British or French nuclear weapons programmes, and accept such weapons on German soil, in exchange for their protection.[13]

Seven EU member states – four of them NATO countries – believe that the US nuclear security guarantee has become less credible under Trump. This includes two states from the Conflicted group, Sweden and Germany, as well as France – unsurprisingly, given that France never accepted total reliance on the US umbrella, and based its policy of a national and independent deterrent on such doubts. The survey nevertheless shows that no fewer than 22 member states – all of them NATO members – believe that the US guarantee remains credible. Three – Estonia, the UK, and Poland – even believe it has become more credible, perhaps judging that the new unpredictability of the guarantee will act as an added deterrent.

Doubts about US commitment to the alliance are nothing new, in any case. Europeans may yet still need to face the prospect of the US failing to fulfil its Article 5 obligations. But Trump’s arrival has done next to nothing to jolt Europeans into more substantive thinking about nuclear and other strategic matters.

Proliferation crises and other nuclear concerns

Non-proliferation was always an issue EU member states were able to agree and act on. The role of the E3 (France, Germany, and the UK), of the EU high representative, and of EU sanctions in managing the crisis around Iran’s nuclear programme and in reaching the July 2015 agreement with the Iranian government illustrated this.

Non-proliferation remains an area of concern, as well as of consensus. At the time that ECFR conducted its research (before Trump withdrew the US from the Iran deal), several countries spread across the five groups – ranging from Portugal and Ireland to Germany – named the situation on the Korean Peninsula as their top nuclear-related concern. In contrast, the situation in the Middle East caused less worry among most Europeans: no member state named it as its top priority.

This commitment to non-proliferation helps explain why member states see any merits of nuclear weapons in the European security context as not applicable to other parts of the world. Two-thirds of EU countries believe that nuclear deterrence makes Europe more or even “much more” secure, and nearly half think that this benefits the rest of the world as well. But the same logic does not appear to apply to other regions: a plurality of member states fear that local nuclear deterrence makes the Middle East and Asia less or even “much less” secure. As a consequence, most member states believe that the EU should continue trying to resolve major proliferation crises – including that on the Korean Peninsula, where Europe has had a limited role so far. Just a small minority believe that the only meaningful thing that Europeans can do, if anything, is to support the US.

Still, it is important to note that proliferation crises are not the only source of concern in Europe. In addition to Russia, another consistent top priority of nuclear-related security concern across Europe is nuclear and radiological terrorism. This is a particular concern for Conformists (Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Spain) and Neutrals (Austria and Cyprus). The risk of a nuclear military accident generates some concern among Neutrals (Malta and Finland). Few cited the Middle East, tensions in south Asia, or China’s development of its military nuclear programme as key worries.

Attitudes towards nuclear disarmament

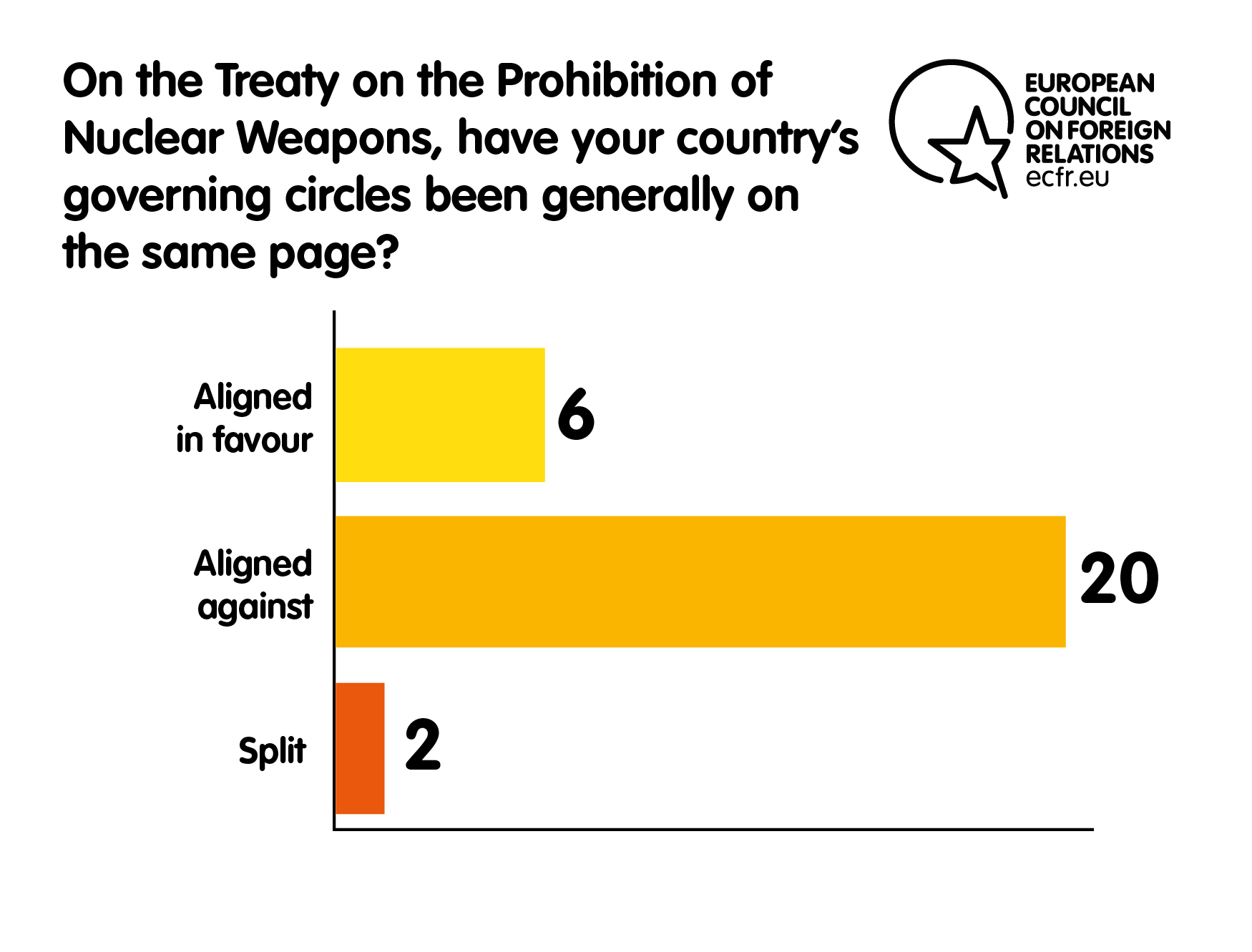

In contrast to non-proliferation, disarmament has long been a more problematic issue for Europeans – due not least to the ambiguity of the term. Does it mean mere reductions or full abolition? With the renewal of abolitionist efforts under the banner of the TPNW, this uncertainty has now turned into a strong divergence between member states.

The survey confirms that a clear majority of member states are in favour of nuclear disarmament, at least in principle. This includes the nuclear-armed states, the UK and France. This consensus holds when it comes to what the next steps should be on disarmament: countries point to a variety of specific measures, including the entry into force of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), which has the support of two-thirds of member states. Half of member states support the negotiation of a Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty (FMCT), a goal endorsed by common EU positions, as a priority. That said, despite general support for moving towards disarmament, there is no consensus on what the next step should be. This likely reflects the low level of debate on this issue, but also points to a barrier to making genuine progress on this front.

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, EU countries are not quick to pass the buck solely to the US and Russia: support for a new round of reductions in both strategic and non-strategic weapons lags behind other available options, such as the CTBT and the FMCT, and reductions shared across all nuclear powers. Of the two nuclear weapons states, the UK is particularly in favour of reductions involving all states – likely out of a preference for multilateral rather than unilateral disarmament – while France joins the majority in supporting rules-based measures (such as the treaties) rather than arsenal reductions.

Reservations begin to show, and divisions to appear, on whether the current global security environment allows for total and/or unilateral disarmament. No issue reveals this better than the fierce debate around the TPNW, which is the most divisive nuclear issue within the EU at the moment. The problem is not so much that member states are split: only Austria, Ireland, Malta, Cyprus, and Sweden voted in favour of it at the UN (Finland abstained), while just Austria and Ireland signed it, and Austria alone ratified it. But this issue has polarised and effectively locked down discussions on disarmament at the EU level. As NATO members disagree with Neutrals on the issue, the alliance’s official response to the treaty has been that nuclear disarmament should happen in a “step-by-step and verifiable way” and “on the basis of reciprocity”. Rather than creating “the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons”, NATO said, the treaty risks undermining the current non-proliferation regime.[14]

Missile defence

US engagement with Europe has actually deepened in one respect: through the construction – already under way – of missile defence infrastructure. As then US president Barack Obama decided to scale this programme back, its rollout attracted less controversy than it might have done. But the trend has reversed under Trump, and the programme is now in full swing in Poland and Romania.[15]

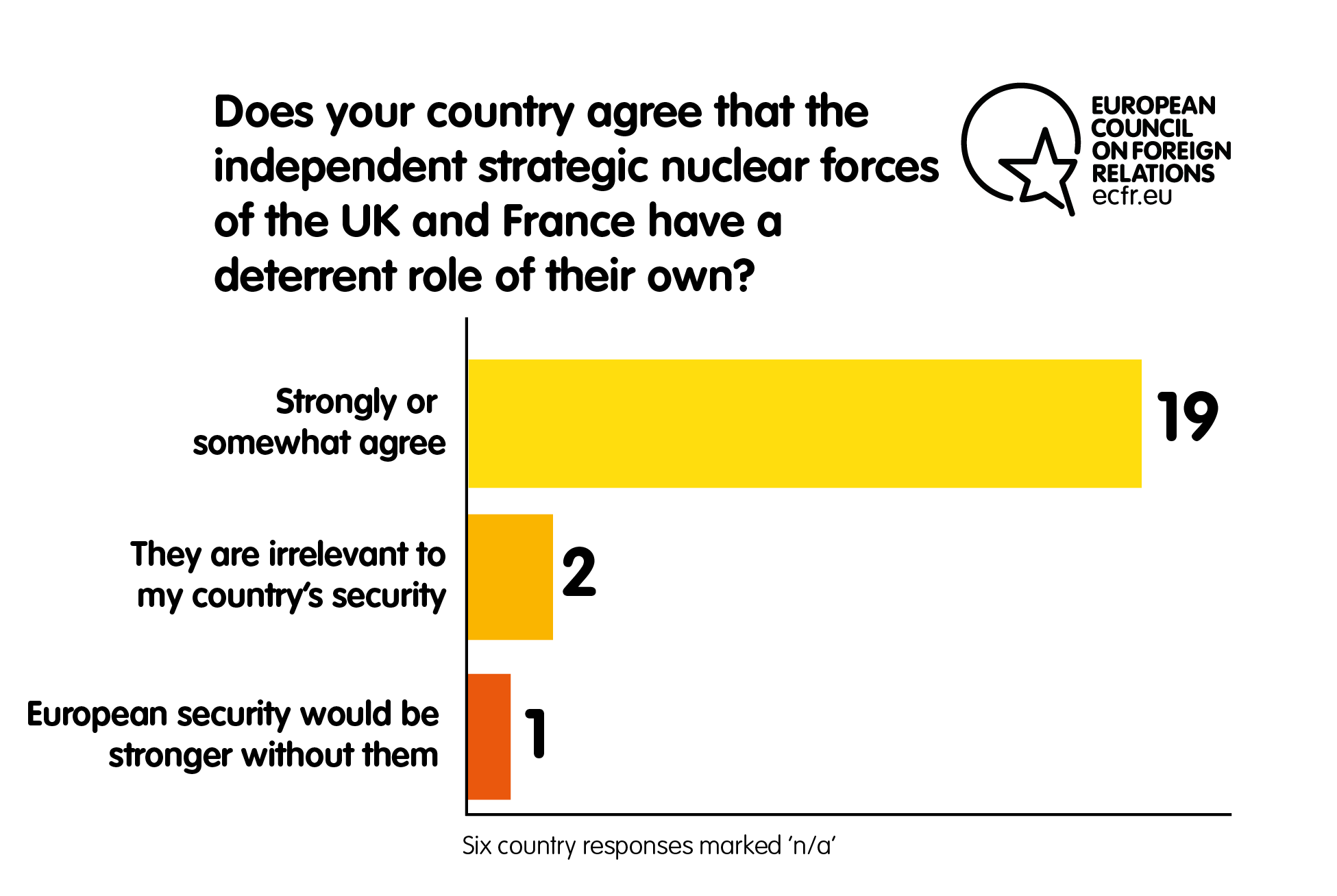

Despite Europeans’ traditional ambivalence on this issue, the survey shows that a majority of member states are supportive of missile defence deployments in Europe. Only Malta and Ireland believe that it is strategically destabilising and likely to provoke Russian countermeasures. And, despite the risk of their deterrent ultimately being compromised by effective strategic missile defence, the UK, and even France, have still joined the ranks of countries that are supportive of the programme.

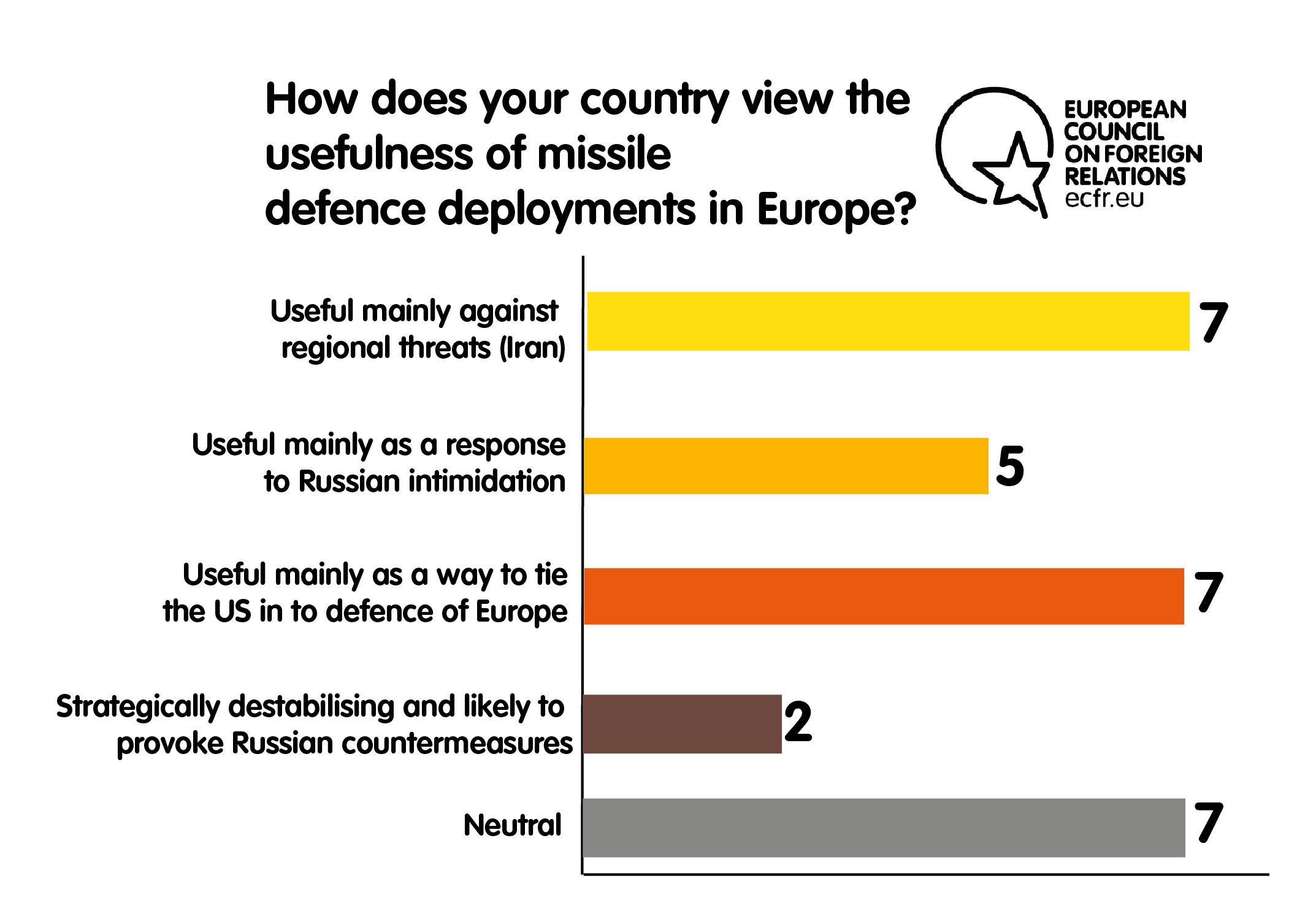

But the reasons for this support provide yet another hint at Europeans’ lack of strategic cohesion on these issues. A plurality of member states stick to NATO’s official rationale that it needs these defence systems to counter potential regional threats. But an equivalent number of countries (coming from both Pragmatist and Conformist ranks) admit that they find such missile defence systems useful first and foremost as a way to tie the US to the defence of Europe. And a smaller but similar number of them believe missile defence is useful mainly as a response to Russian intimidation. This group includes Poland and Romania, which are both True Believers and play a key role in the deployment of the new system.

NATO

The vast majority of member states agree that nuclear deterrence is central to NATO; indeed, ten member states hold that this has become even more important in the current climate. Those that agree that the nuclear dimension is “problematic” all belong to the Neutrals group.

For NATO members, national positions are primarily influenced by consultations and decisions through the alliance (and, consequently, by the US) rather than by consultations with other European partners. The difficulty of reaching common EU positions reinforces this pattern. For instance, as noted above, NATO played a key role in encouraging its EU members to oppose the very notion of a treaty that seeks to prohibit nuclear weapons.

This aside, coordination between EU member states is rare, although it does take place formally and informally between neighbours or key member states such as France, the UK, and Germany. Bilateral cooperation between France and the UK is the obvious exception to this pattern. This cooperation – which entails political and legal commitments, and technological collaboration, such as that on simulating nuclear weapons tests – is set to continue despite Brexit.

***

These findings show that most EU member states feel vindicated in their established positions, whether in justifying a national deterrent, embracing the abolition of nuclear weapons, or underlining the importance of the transatlantic umbrella. The Conflicted are the rare exception to this pattern, as they struggle to reconcile their traditional views with the immediate issues they face. In Sweden, debate rages within the government on both the opportunities and the consequences of ratifying the TPNW. The Swedish government is struggling to maintain consistency between its traditional pro-disarmament stance and the attempt to strengthen defence ties with the US it has made out of concern about its immediate security environment. But even Conflicted countries’ positions have still not changed significantly. In Germany, the recent debate on a national deterrent was unprecedented, but it concluded quickly by settling back into its more traditional stance.

The picture emerging from ECFR’s survey results and the history of this contested arena is one of a continent that is not devoting enough intellectual energy to the subject. The EU has not adapted its thinking on nuclear issues to the post-cold war era, let alone to the new age of Russian revanchism and potential regional proliferation.

A European nuclear deterrent?

In Germany this year, Putin and Trump between them prompted a new flurry of interest in an old idea – that of a European nuclear deterrent.[16] That notion actually covers a number of different options, ranging from France and the UK ceding ultimate control of their deterrents to (already existing) unilateral statements that national nuclear forces are “de facto” protecting more than just national territory. The usual variant is based on France and Britain providing the umbrella, with their non-nuclear partners and protégés finding ways to share the burden – politically, financially, and, perhaps, operationally.

The notion of a European nuclear deterrent has been around for decades. France and Germany discussed the idea, sotto voce, at several points in the twentieth century. At times, it was Germany that reached out to France: Konrad Adenauer did so, but Charles de Gaulle halted any further progress as after he was elected in 1958. Later, Helmut Schmidt suggested that France include Germany under its nuclear umbrella, in exchange for financial support for the French nuclear programme. Germany even glossed its 1975 ratification of the NPT with the explicit reservation that “no stipulation in the treaty can be construed to hinder the further development European unification, especially creation of a European Union with appropriate capabilities”.[17] More recently, France proposed “concerted deterrence”, without receiving much by way of response from Germany, or from anyone else.

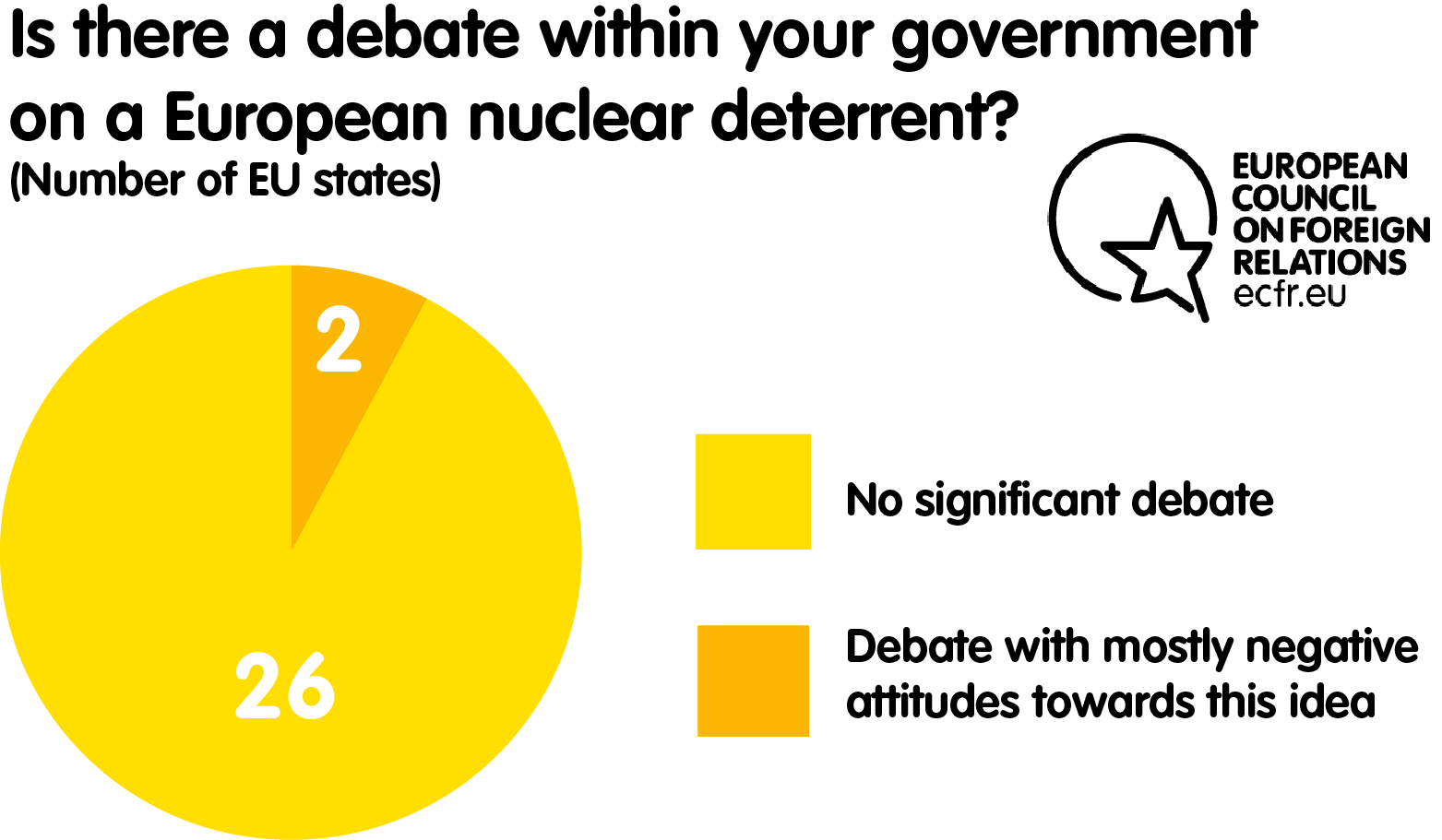

Striking though the re-emergence of the subject in Germany was, it has hardly caught fire. German official circles have shown no public interest in the matter. Paris and London have remained silent. Even Kiesewetter said that: “he hoped to spur Mr. Trump to end doubts over American security commitments to Europe, rendering unnecessary the nuclear ‘Plan B.’”[18] And, as the survey confirms, this is just one more nuclear issue that most Europeans would greatly prefer to ignore.

The Euro-deterrent idea’s failure to gain official traction is hardly surprising. Why antagonise Trump? And why encourage the Kremlin to take the US nuclear guarantee to Europe less seriously? It was not, after all, as though a European deterrent – that is, the extension of British and French nuclear deterrence to European partners and allies – was an immediately credible concept. Euro-deterrent talk tends to prompt only more questions: Would London and Paris be willing to offer such a guarantee? If so, do they have adequate capabilities? Should they be trusted? What would they expect in return? And above all at this point in history: how could such a development possibly be squared with Britain’s decision to leave the EU?

So if a Euro-deterrent were ever to progress from newspaper provocation to serious policy option, the initial onus would be less on the supposed beneficiaries to appeal for such protection than on the two nuclear powers to begin to signal that they might really be willing and able to offer such extended deterrence, if that is what their partners wanted.

Implausible though it may sound today, Brexit should not necessarily be seen as a terminal blow to such a possibility. A UK guaranteeing its rejected partners’ security as it leaves the EU may seem unlikely; and a bitter conclusion to the Brexit negotiations could put an end to any such notion for a generation. And it does not help that the leader of the Labour opposition is a longstanding unilateral disarmer, albeit one at odds with his own party’s policy of supporting the deterrent. Yet, counterintuitively, the period since the Brexit referendum seems, if anything, to have whetted the UK government’s appetite for a “deep and special relationship” in foreign, security, and defence policy with the EU27. “We are leaving the EU, not Europe”, the British insist; and the prime minister reiterates that Britain will remain “unconditionally committed” to Europe’s security. Moreover, the British have a deep historical attachment to the idea that their nuclear weapons are maintained as much as a service to allies as for national purposes. They invented the doctrine of the “second centre of nuclear decision-making within the alliance” precisely to bolster this contention. Their relevant forces have always been fully committed to NATO. Extending deterrence, the UK could argue, is nothing new.

Despite being the leading proponent of European strategic autonomy, France has been more ambivalent on this subject. On the one hand, it has always insisted that its deterrent is essentially national and independent. Even after it rejoined the NATO military command in 2009, France has declined to commit its nuclear forces to the alliance, staying out of NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group in particular. On the other hand, the French deterrent was never designed to exclusively confuse national vital interests with the boundaries of the French territory; and France’s official positions have repeatedly made clear that it amounts to de facto European protection.[19] Although France never trusted extended deterrence by others as a credible security guarantee for itself, the fact is that, as one observer has commented, it “paradoxically has an interest in others believing in it for themselves: beneficiary states, so as not to be tempted to develop their own nuclear capabilities; and potential adversaries, so as to be deterred from attacking”.[20]

As a consequence, in 1995, France’s then prime minister, Alain Juppé, proposed the notion of “concerted deterrence”, stressing the need for a dialogue between France and Germany rather than a simple “extension” of the French nuclear umbrella.[21] This has since become a standard reference point for the French authorities’ nuclear doctrine. It has, however, tended to fall flat because of the lack of interest, or even negative reaction, from other European countries, especially Germany – at which these ideas were largely directed.

Nonetheless, since the end of the cold war, France and Britain have been pursuing a slow but steadily developing dialogue on nuclear matters, beginning with a bilateral Nuclear Commission to deepen mutual understanding of respective doctrines and programmes, and progressing to the 2010 Lancaster House treaty on nuclear cooperation. Strikingly, the treaty’s preamble includes the words: “Bearing in mind that they do not see situations arising in which the vital interests of either Party could be threatened without the vital interests of the other also being threatened”.[22] “Vital interests” here is code for “things that matter to us so much that you cannot attack them without risking nuclear retaliation”. In other words, Britain and France have already given each other a sort of oblique mutual nuclear guarantee, and they have even done this in treaty form.

If a mutual nuclear guarantee, why not a joint guarantee to non-nuclear European partners and allies? Few doubt Emmanuel Macron’s appetite for bold policy departures or his belief in the need for Europeans to stand on their own feet: his September 2017 Sorbonne speech spoke of the “gradual and inevitable disengagement” of the US from Europe.[23] The section of France’s new Strategic Review that addresses nuclear matters reiterates that “the definition of [France’s] vital interests cannot be restricted to the national scope, because France does not conceive its defence strategy in isolation, even in the nuclear field”,[24] and that “beyond these commitments, the political reality implies that an external aggression against European integrity or cohesion would severely affect our interests”.[25] Flirting with a wider definition as the Strategic Review does is significant, particularly given the precedent of close Franco-British post-cold war cooperation in this area. Yet France stopped short of explicitly extending its nuclear umbrella to all, and even some, of its European partners’ “vital interests”.

What next? The history of European defence efforts to date suggests ‘not much’. Nuclear issues are uniquely sensitive; and ECFR’s survey confirms that Europeans have no current appetite for putting Euro-deterrence on any formal agenda. The path of least resistance will be to cling to the belief that the US nuclear guarantee to Europe is, and will indefinitely remain, rock solid – and to continue to talk about the need for European strategic autonomy while ignoring its fatal lack of a European nuclear underpinning.

But just hoping for the best is not a policy. For the reasons discussed above, no immediate European initiative to declare strategic nuclear autonomy is practicable, desirable, or even conceivable – but a strategy to hedge against the uncertainties of the future is certainly available. With all the necessary caveats (over time, and subject to Brexit), the UK and France could convert the idea of a European deterrent from a mere notion into a credible offer, by thickening their bilateral nuclear cooperation and hinting ever more clearly at their readiness to protect others.

Lancaster House was not the last word on bilateral nuclear cooperation. There are various areas in which the UK and France could take that cooperation further – nuclear propulsion, for example, or joint target planning. The latter could be a particularly useful way of signalling that “any aggressor” – i.e. Russia – disposed to ignore the retaliatory threat posed by the minimum deterrent forces and second-strike capability of the UK or France individually would have to weigh the damage (in truth, devastating) that both could cause in combination.

The two countries could combine closer and discreetly publicised bilateral cooperation with scaling up their declaratory policy to be increasingly explicit that they would view armed aggression against EU partners as threatening their own “vital interests”. The aim would be to create a sense of de facto extended deterrence: “we have each other’s backs, and we have yours too, even if you don’t yet feel you want or need it.”

Of course, it is inconceivable that France and the UK should embark on this without being confident that other countries in Europe would actively support, or at least tolerate, this new trajectory. While the Welt am Sonntag question focused on a bomb for Germany, the issue may instead be whether the country should welcome someone else’s bomb. Yet, it is hardly imaginable that a government-to-government agreement would suffice given the German public’s potential reaction.

In France, there is the start of a discussion about whether Macron ought to make the same commitment to the defence of German “vital interests” that France and the UK have made to each other since 1995.[26] Indeed, rather than Germany developing its own bomb – and breaking its commitments under the NPT and the Two Plus Four Agreement (which led to German reunification) – the Europeanisation of the French deterrent is a topic of discussion in Berlin.[27] Over time, the two European nuclear powers could hope to draw relatively receptive EU partners into nuclear discussions, eventually firming these up in into nuclear consultation (rather than a simple unilateral extension of the nuclear umbrella) and some form of burden-sharing.

The development and acceptance of such a “European vocation” for the British and French nuclear deterrents would be the work of a decade or more. Events during that time could easily combine to render the process unnecessary. But, given the unpredictability of the twenty-first-century world and Europeans’ apparent belief in the need to build strategic autonomy, it would be wise for them to begin the journey along this road.

Conclusion

The primary finding of ECFR’s research is that, whatever thought Europeans have given to their strategic interests and policies (arguably, they have given little), almost none has been about the nuclear dimension of European security. This was true when the “pivot to Asia” under Obama prompted a touch of worry but resulted in no significant reaction. It is still true under the Trump administration, with its “America First” banner and the president’s deeply held instinct that NATO is “obsolete”. The Conflicted countries are only the most visible illustration of the fact that past attitudes are no longer sustainable. Familiar questions about nuclear deterrence are slowly forcing themselves onto others, while the growing gap between Europe’s nuclear environment and the solidity of the US security guarantee may render such questions yet sharper for all Europeans.

The possibility of decoupling from, or just a more distant, US – a traditional concern across Europe during the cold war – cannot be escaped. Angela Merkel may have echoed Macron in recent remarks about the need for Europe to become more self-reliant in security matters; German attitudes towards defence issues have clearly evolved in the last few years.[28] Europeans need to do some harder thinking than they have up until now; they should do this before a possible political and even strategic alignment between the US and Russia takes its toll on those caught in between.

The second main finding is that there are many more dimensions that are required to move towards strategic autonomy than addressing nuclear issues. No one expects Germany to overcome its nuclear taboo any time soon: the newly sparked debate about a German bomb has seen no enthusiasm for such a proposal. Germany remains far off even reaching NATO’s 2 percent of GDP defence spending target. Still, moving along on conventional defence while leaving aside decisions and even discussions on the nuclear issues is not a sustainable approach. In particular, Europeans need to be able to weigh in much more directly and forcefully on the development of the European security order, whose nuclear dimension they cannot avoid. The combination of missile defence, the deployment of non-strategic weapons, the TPNW, and the evolution of both US and Russian nuclear postures should bring Europeans towards confronting these issues head on.

The third key point is that EU countries must acknowledge the almost total evaporation of the intellectual investment made in the last century in understanding and thinking strategically about nuclear deterrence. The case in favour of these weapons – as guarantors of peace and stability – has gone largely by default. The fact is that it took a strong US lead (and NATO statement, providing the necessary arguments) to ensure that most Europeans stayed out of the UN initiative to “prohibit” nuclear weapons. This clearly indicates that most of the strategic thinking on nuclear issues stems from the US, at a time when European impetus on the topic seems essential.

The international landscape is changing quickly. Europeans perceive it, whether through their concern about a less predictable US nuclear alliance or in news headlines on the situation in the Middle East or even on the Korean Peninsula. But they seem paralysed by these changes rather than prompted to confront them. And yet more factors will only add to this turmoil. Countries that are still debating their stance on the TPNW or whether and how to replace their dual-capable aircraft fleet will find themselves buffeted by all sorts of demands if they do not now take some time to sort out their strategic positions.

In this context, it is hard to overcome the contradiction between idealist support for a bold disarmament agenda and the realist assessment of a dangerous world. This is even more difficult now than in 2009, when the Obama administration called for a “world without nuclear weapons” and yet prepared for a major modernisation of the US arsenal. The increasing challenge of this issue is not limited to the Conflicted countries. The growing differences – between public opinion and governments, between parliaments and governments, and within and between EU governments – are likely to burst out more obviously into the open at some point. This will have ramifications beyond countries where political disagreements on nuclear issues are greatest.

Fourth, there is now a nascent discussion about a Euro-deterrent – whatever form this might eventually take. But this discussion urgently needs to expand and deepen. Unless this debate acquires new energy and sophistication, the worst result of it would be to conclude with the status quo by default. Recognising that nuclear proliferation in Europe is a non-starter is one thing but failing to contemplate the Europeanisation of the British or French deterrent, or both, would only leave Europe facing a strategically dangerous dead end. Europe’s dependence on a faltering US security guarantee could leave the continent exposed to a variety of threats.

This is not just about the relationship member states have with the US. Above all, it is about Europeans’ collective responsibility to themselves; and about governments’ responsibility to their peoples, however unattractive it looks to broach the nuclear issue. France and the UK should deepen their nuclear relationship and develop their declaratory policy; they must also prepare for a time when a joint offer to provide that capability might seem both credible and welcome to their European partners.

In short, Europeans need to overcome their deep-seated reluctance to think about nuclear issues anew. They must prise their eyes open and take a good hard look at the implications of the strategic autonomy they have endorsed. Soberly, seriously, and with some resolve, Europeans must answer the question of whether they can ever enjoy such autonomy unless they possess a deterrent capability of their own.

If it is to happen, progress on these issues will require far clearer thinking about Europe’s threat perceptions, its security interests, and its strategy for confronting the current and future international environment. As such, the nuclear dimension is not the only indicator, but it is a telling one – revealing both the need to move forward and the distance to be closed by Europeans who wish to do so.

Austria

Perception of nuclear threats

Austria perceives Russia as a threat, but not a major one. Austrian governing circles are instead preoccupied with other serious nuclear-related concerns, including: nuclear and radiological terrorism, North Korea’s nuclear weapons, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Overall, Austria’s strategic assessment does not cite nuclear weapons as a priority.

Influence of public opinion on the political debate

Austria’s position is unique – as a non-NATO member it is a neutral country, and it is also a strong proponent of nuclear abolition. Government and public opinion are largely aligned on nuclear weapons policy.

Stance on disarmament

Austria has initiated international-level conferences on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons and was the originator of a document that became a humanitarian pledge signed by 127 countries in 2014. In December 2016, Austria co-sponsored UN Resolution 71/258, which the UN General Assembly adopted, leading in 2017 to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

For Austria, the next steps on nuclear disarmament should be as follows: a reduction in stockpiles involving all states that possess nuclear weapons; the entry into force of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty; advances in methods for verifying nuclear disarmament; and the adoption of confidence-building measures by nuclear weapons states.

European coordination and perception of the need for a European political and/or military role

Austria coordinates closely with like-minded countries such as the Nordic states, as well as non-EU members such as Norway and Switzerland. Austria believes that the EU should play a role in Iran’s nuclear programme.

Belgium

Perception of nuclear threats

Belgium believes that nuclear weapons pose a significant – but not priority – threat. It perceives Russia as a threat irrespective of the latter’s nuclear weapons. Belgium considers Russia to be a frustrated power that seeks to regain, to some extent, part of its lost influence. Nevertheless, Belgian officials do not consider Moscow a major threat: the government sees real possibilities of cooperation with Russia on a range of issues, including terrorism.

Influence of public opinion on the political debate

Belgian citizens do not cite the nuclear issue as a major concern. During the Euromissile crisis, large demonstrations against the deployment of US nuclear weapons took place on Belgian soil. This led the government to postpone the installation of the weapons.

Stance on disarmament

In principle, Belgium strongly supports nuclear disarmament. However, federal officials believe that a non-nuclear world is currently out of reach: growing geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, in Asia, or even in eastern Europe make it difficult, for the moment, to seriously consider the possibility of massive, worldwide disarmament. The only parties opposed to this view in Belgium have far-left leanings or are Green party members, who currently have very limited influence on policymaking.

For Belgium, the next steps on nuclear disarmament should be the entry into force of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty and the launch of negotiations on the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty.

European coordination and perception of the need for a European political and/or military role

The “European federal dream” has formed the centrepiece of Belgium’s foreign policy in the last few decades. Were any form of European deterrence architecture to emerge, France would be its backbone. However, Belgian officials mostly see this as a kind of utopia and, therefore, prefer to resort to NATO when tackling such issues.

Bulgaria

Perception of nuclear threats

Bulgaria’s main nuclear security concern is the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and their means of delivery – nuclear and missile programmes. The management of nuclear waste also figures among its most prominent concerns.

Bulgaria perceives Russia as a threat and believes that its status as a nuclear power amplifies this threat. The annual Report on the State of National Security of the Republic of Bulgaria, published in September 2017, states that “the actions of Russia are a source of regional instability and threaten our main goal for a unified, free and peaceful Europe”. It also notes that Bulgarian political parties and other stakeholders hotly contested “the militarisation of Crimea and breaches of the conventional arms agreements”.

Influence of public opinion on the political debate

The geopolitical context has brought the general public round to favouring nuclear deterrence – but only in the sense of upgrading Western nuclear weapons.

Stance on disarmament

Sofia considers itself to be strongly in favour of nuclear disarmament. However, it put none of its weight behind the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). As one expert contributing to this study explained: “nuclear-weapon states have not joined it and its entry into force will not result in the destruction of even a single nuclear device.” Bulgaria believes that the treaty threatens the legitimacy of the TPNW and diverts the international community’s attention away from more immediate tasks in nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation.

For Bulgaria, the next steps on nuclear disarmament should be as follows: the entry into force of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty; the launch of negotiations on the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty; and the adoption of confidence-building measures by nuclear weapons states.

European coordination and perception of the need for a European political and/or military role

There is no significant debate about the need for a European deterrent. Traditionally, Bulgaria believes that the United States has the primary strategic role in defending Europe, and fears that western European powers are less committed to the country’s security. Bulgarians generally view French and British nuclear forces as irrelevant to their country’s security.

Croatia

Perception of nuclear threats

Croatia considers threats such as terrorism, cyber warfare, and intra-state conflicts that could lead to regional destabilisation to be more important than nuclear threats. It perceives Russia as a threat irrespective of the fact that it possesses nuclear weapons.

Influence of public opinion on the political debate

The general public does not name nuclear deterrence as an important issue and no significant debate on the topic has taken place in recent years.

Stance on disarmament

Croatia subscribes to the international consensus on nuclear disarmament: it is a signatory party to all major international agreements on the non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, arms control, and disarmament. However, Croatia’s governing circles elites were all against the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Zagreb claimed that US nuclear weapons were essential to Croatia’s security. It believes that the next step on nuclear disarmament should be a reduction in stockpiles involving all states that possess nuclear weapons.

European coordination and perception of the need for a European political and/or military role

Other European Union and NATO members influence Croatia’s policy on nuclear issues through formal mechanisms. As a rule of thumb, the Croatian foreign and defence ministries align themselves with NATO and EU positions on nuclear issues, issuing statements that criticise breaches of international law and treaties (such as those by North Korea, China, and Iran) or supporting EU and NATO decisions on security issues.

Cyprus

Perception of nuclear threats

Cyprus is very worried about nuclear activities that take place in a non-verifiable and non-transparent manner. However, Turkey’s occupation of the island is Cyprus’s main security concern. Nuclear threats are not one of Cyprus’s security priorities: the nature of its nuclear concerns, according to our survey, has more to do with nuclear and radiological terrorism, as well as nuclear accidents.

Cyprus does not perceive Russia as a threat. Instead, it sees itself as having close historical ties to Russia. In October 2017, the presidents of Russia and Cyprus signed a joint action plan for the 2018-2020 period, which covers politics, economics, energy, defence, international issues, and European Union affairs. Cyprus is one of just eight countries that say that Europeans should ignore Russia’s alleged violations of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.

Influence of public opinion on the political debate

Cyprus does not regard nuclear arms as a threat, and engages in no significant public debate on nuclear-related issues. Even recent nuclear threats in Asia did not resonate in the country’s public debate.

Stance on disarmament

Cyprus is strongly in favour of nuclear disarmament and sees the total elimination of nuclear weapons as the ultimate goal of this process. It also strongly supports the entry into force of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and would like the measure to be universally adopted.

European coordination and perception of the need for a European political and/or military role

Cyprus sees French and British nuclear forces as irrelevant to its security. Cyprus is one of the small number of countries within the EU to hold strong anti-nuclear views.

Czech Republic

Perception of nuclear threats

The Czech public does not exhibit much interest in topics related to nuclear deterrence or weapons except when there is media coverage of the North Korean nuclear and missile programmes.

The Czech Republic sees Russia as a threat amplified by its nuclear weapons. Some Czech experts argue that Russia would be less hesitant to use nuclear weapons than NATO would, expressing concern about a lack of democratic control over Russia’s nuclear weapons and their possible use. Other experts think that Russia is a responsible and stable nuclear power. There are no public documents or speeches from Czech officials that name Russia as a threat to the country.

Influence of public opinion on the political debate

The possible deployment to the Czech Republic of radar as part of the US missile defence system resonated strongly with the public in the late 2000s. At that time, two-thirds of Czechs were against such a deployment.

Stance on disarmament

The Czech Republic was strongly opposed to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. It thinks that this treaty challenges transatlantic ties and NATO. The Czech Republic does not believe that nuclear disarmament is achievable and suggests instead focusing attention on the Non-Proliferation Treaty regime.

Should new steps be taken in the framework of disarmament, the Czech Republic would pursue the following, in priority order: new US-Russia reductions in strategic weapons; the entry into force of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty; the launch of negotiations on the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty; advances in the verification of nuclear disarmament; and the adoption of confidence-building measures by nuclear weapons states.

European coordination and perception of the need for a European political and/or military role

Consultations on nuclear issues mainly take place with the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defence and with the German and French ministries of foreign affairs. NATO remains the Czech Republic’s primary security provider.

Denmark

Perception of nuclear threats

Denmark generally perceives nuclear threats as less important than most other threats. Denmark does not perceive Russia as a threat despite the fact that it possesses nuclear weapons.

Influence of public opinion on the political debate

A large majority of the Danish public is against nuclear deterrence. During the 1970s and the 1980s, Denmark’s relationship with the United States and NATO became particularly strained over nuclear weapons, which Denmark decided not to station on its territory. Since then, Danish policymakers have made efforts to significantly distance themselves from the policies of the 1980s, not least because NATO and the relationship with the US is the fundamental framework for Danish foreign and security policy. There is, however, still a strong domestic anti-nuclear sentiment. The issue remains a balancing act for Danish governments, which try to take account of both popular anti-nuclear sentiment and the fact of membership of a military alliance with nuclear capabilities at its core.

Stance on disarmament

All political parties are in favour of nuclear disarmament but, when in power, they have not made significant moves towards making this a reality. While a majority oppose the United Nations’ recent effort to adopt the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, pacifist and left–red/green alliance Enhedslisten argued that Denmark should support any attempt to limit nuclear weapons.

For Denmark, the next steps on nuclear disarmament should include: new US-Russia reductions in strategic weapons; new US-Russia reductions in non-strategic weapons; and reductions in nuclear weapons involving all states that possess them.

European coordination and perception of the need for a European political and/or military role

Denmark believes that the European Union should take action on Iran’s and North Korea’s nuclear programmes. Denmark also coordinates with other NATO members on nuclear weapons issues. However, since the Treaty of Amsterdam (1997), it has formally benefited from an opt-out from the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy. Consequently, Denmark is excluded from EU foreign policy discussions with defence implications and does not participate in foreign EU missions with a defence component.

Estonia

Perception of nuclear threats

Estonia views nuclear deterrence and the use of nuclear assets as a last resort, though one it is prepared to support. Estonia perceives Russia as a threat amplified by its nuclear weapons; Tallinn’s main concern is that Moscow will threaten to use tactical nuclear weapons as a component of a hybrid warfare scenario against NATO forces in the Baltic region.

Estonian experts also believe that NATO should signal its willingness to use nuclear weapons against Russia if needed. In such a scenario, the Baltic states would be part of a wider Russia-NATO confrontation.

Influence of public opinion on the political debate

In general, the Estonian-speaking majority is in favour of nuclear deterrence and the Russian-speaking minority is critical of it. The political elite has stressed several times that nuclear deterrence is a critical component of NATO’s model in the region and should be applicable if Estonia comes under threat.

Stance on disarmament

Nuclear deterrence is vital to Estonia’s defence strategy. The country would not support steps towards nuclear disarmament if this would put it at risk.

However, should new steps be taken in the framework of disarmament, Estonia would pursue the following, in priority order: new US-Russia reductions in strategic weapons; new US-Russia reductions in non-strategic weapons; and reductions in nuclear weapons involving all states that possess them.

European coordination and perception of the need for a European political and/or military role

As US-based nuclear deterrence plays a central role in Estonia’s defence and deterrence strategy, the country supports the US position unconditionally. Estonia views Western nuclear capabilities as sufficient to deter Russia. The main critical variable is a readiness to use those assets. However, Estonia has the US in mind when it talks about NATO, as it views the United Kingdom and France as insufficiently capable.

Finland

Perception of nuclear threats

Finland’s key strategic documents refer to nuclear threats only in passing. The government’s most recent white paper on defence policy mentions nuclear threats twice. Firstly, in relation to Russia, it notes that “much as in the West, Russia focuses the material development of its armed forces on long-range strike capability and precision-guided weapons, manned aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles, robotics, nuclear weapons, air and space defence as well as digital command & control and intelligence systems (C4ISR).” Secondly, it argues that “wide-ranging chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) threats persist”.

Influence of public opinion on the political debate

Finland has a long-standing tradition of promoting nuclear arms control and non-proliferation – a product of Finns’ general distrust of great power politics and Finland’s vulnerable geopolitical position and non-membership of NATO. Finns’ interest in, and awareness of, nuclear issues decreased after the end of the cold war.

Stance on disarmament

During the cold war, Finland actively promoted the idea of a Nordic nuclear weapons-free zone. Finland has also been an active supporter of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). However, recently, Finland’s foreign policy leadership (comprising the president, the government, and the civil service) has opposed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapon (TPNW). It posits that the treaty will not contribute to nuclear disarmament because nuclear-armed states have not signed up to it. Instead, the TPNW could weaken existing agreements – most notably the NPT, which continues to be the cornerstone of Finland’s nuclear policy.

For Finland, the next steps on nuclear disarmament should include: new US-Russia reductions in strategic weapons; new US-Russia reductions in non-strategic weapons; reductions in nuclear weapons involving all states that possess them; the entry into force of the CTBT; and the launch of negotiations on the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty.

European coordination and perception of the need for a European political and/or military role

Other EU member states and Nordic countries formally influence Finland’s policy on nuclear issues. Although Finland is not a NATO member, it regards the US presence in Europe as essential to its security.

France

Perception of nuclear threats

The Strategic Review on Defence and National Security, published in October 2017, identifies terrorism as the most important threat to French national security. Armed forces minister Florence Parly’s foreword to the review states that: “Jihadist terrorism remains the most direct threat our country faces today. France and its European neighbours have been hit hard.” However, nuclear threats feature prominently in the document, which links them with the resurgence of great power rivalries. In fact, the review’s introduction argues that: “given that the nuclear factor is set to play an increasing role in France’s strategic environment, maintaining over the long-term our nuclear deterrent, the keystone of the Nation’s defence strategy, is essential now more than ever.” France considers the proliferation of nuclear weapons to be a major threat.

France does not directly characterise Russia as a threat in official documents but sees its security activities and its strategic intimidation policy as a threat to French national security. France recognises that Russia’s nuclear programme is a central element of Russian power but that it may pose a threat to France when combined with its aggressive behaviour. The Strategic Review contains a chapter dedicated to “Issues arising from renewed Russian power”. France acknowledges that Russia’s efforts to modernise its military, including its nuclear deterrent, launched in the 2000s and accelerated since 2010, are already yielding significant results.

Influence of public opinion on the political debate

The general public is in favour of nuclear deterrence and believes it should be modernised by renewing the French arsenal to preserve credibility – increasingly so, according to the defence ministry’s 2017 Defence Barometer. Still, there is more tacit approval than real public debate. This is not because of a lack of public interest but is instead a question of political culture: foreign policy, security, and defence are prerogatives of the executive branch. There is a consensus on deterrence among mainstream parties as it is an integral part of the country’s credibility on foreign policy.

Stance on disarmament

France is in favour of nuclear disarmament – but only if the global security environment improves, given that it is set on a minimal deterrence policy. The government describes its vision as “pragmatic and progressive”. This gradual approach to disarmament is reiterated in the Strategic Review: “Disarmament cannot be decreed but ought to be built gradually. This is why encouraging a realistic process of arms control and confidence-building is important, in order to contribute to strategic stability and shared security.”

European coordination and perception of the need for a European political and/or military role

There were attempts to debate the Europeanisation of deterrence in the early 1990s in France, but French governing circles remain sceptical about this. However, France does officially recognise a European dimension to its nuclear deterrence: the Strategic Review notes the deterrent’s contribution to the overall security of the Atlantic alliance and of Europe. France coordinates with the United Kingdom on nuclear weapons issues. France’s independent nuclear posture still includes its non-participation in NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group, even if the country has gradually acknowledged that its national nuclear forces contribute to the overall deterrence capability of the alliance.

Germany

Perception of nuclear threats

Nuclear threats have recently risen in prominence in Germany’s assessment of the strategic environment. The government’s 2016 white paper on German security policy states that, for as long as nuclear weapons remain a factor in military confrontations, the imperative of nuclear deterrence and nuclear sharing will continue. The white paper highlights the “incalculable risks” of the proliferation of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction. It also points to the risk that terrorist networks might obtain weapons of mass destruction. However, other threats, such as terrorism and hybrid warfare, receive more attention in the white paper and in the government’s official statements. Experts maintain that this does not imply that nuclear threats are not a priority but rather reflects the fact that the German government is reluctant to discuss nuclear weapons in the wider security context.