Under the gun: Rearmament for arms control in Europe

Summary

The decrepitude of arms control treaties in Europe is becoming increasingly apparent at the same time as Russia continues to act as a revisionist power. Russia’s unpredictability and lack of transparency is part of its competitive advantage. It will therefore not give this up by returning to arms-control agreements of the late cold war or negotiating new ones.

Arms control is an integrated part of Russia’s military strategy: to advance its own military position while weakening that of its enemies. As a result, it is open to arms-control agreements that would entrench its military superiority in eastern Europe and prevent the technological gap between Russia and the West from growing. This logic creates an opportunity for the West.

If Europe engages in rearmament, enhances its militaries’ combat-readiness and capacity to quickly conduct large-scale, sustainable deployments to eastern Europe, it will deprive Russia of its relative military superiority. Moscow will then be willing to talk on arms control.

Europeans still need to agree a common approach on what they want to achieve vis-à-vis Russia, however. Otherwise, they will be divided and public support for rearmament will falter.

Introduction

During the cold war, arms control and disarmament agreements helped create a stable equilibrium between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, reducing the risk of unwanted confrontation and gradually increasing mutual trust. Today, such deals have a very different role. The Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty collapsed because Russia withdrew from it. The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty may soon fall apart. States selectively implement agreements such as the Vienna Document and the Open Skies Treaty, creating distrust and ambiguity. Arms control no longer reduces the risk of military escalation, or increases transparency, between the West and Russia.

Much of what has been said and written under the aegis of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) emphasises the need to restore trust between the sides and reframe their threat perceptions. But such efforts seem doomed to fail. Since the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, there has been no way to convince states on NATO’s eastern flank to trust Moscow or regard it as anything but an adversary. Equally, there is no way to change Russian elites’ perception that they are locked in an everlasting struggle for hegemony with the West. Of course, there was little trust or empathy between NATO and the Soviet Union when they first negotiated many of the arms-control arrangements now in jeopardy. Arms control was never meant to help competitors become friends, but to prevent them from sliding into avoidable wars or escalating arms races beyond what they could reasonably afford.

Any arms-control treaty needs to fit into its signatories’ strategic rationale. This is why current treaties fell out of favour in Moscow; the Kremlin’s strategy is to exert influence through fear and unpredictability. As Russia knows it cannot match the West in any sphere of power other than raw military force, it tries to emphasise the threat it poses to the West in this area, aiming to gain international relevance and deter outside subversion of the Russian government. As long as it has a military advantage on its western flank, Russia will not take arms control seriously. However, the West – particularly Europe – can change Moscow’s calculus through improved deterrence. If it is to restore Russia’s commitment to arms control, the West needs to rearm.

Conventional forces

Signed on 9 November 1990, the CFE Treaty was designed to stabilise the military stand-off between the Warsaw Pact and NATO by creating a balance of conventional power. The deal had three main pillars. The first of these set a limit on the number of main battle tanks, armoured fighting vehicles, artillery pieces, combat aircraft, and combat helicopters either side could deploy in Europe, defined as the territory stretching from the Atlantic to the Urals.

The second pillar established zones covering multiple states in which the sides would reduce their deployments of both domestic and foreign troops. The deadline for making these force reductions was 1996, with the sides determining the exact quotas for each state within each zone in separate negotiations. The treaty included troop limitations for northern, central, and southern Europe, as well as for the Leningrad and North Caucasus military districts. This flank rule was meant to prevent local force build-ups intended to intimidate or prepare an invasion of small neighbouring states. Importantly, the treaty only covered the Soviet Union (later Russia) west of the Urals. East of the Urals, Moscow could maintain, deploy, and exercise whatever forces it pleased.

The third pillar of the treaty was inspection rights designed to verify the parties’ compliance with the treaty. The agreement allocated each signatory state an annual quota of inspections that it could use at military sites (such as barracks and air bases) and storage facilities for decommissioned materiel awaiting disposal or conversion to other purposes. Signatory states were forbidden from blocking inspections so long as the request fell within these quotas.

The first two pillars of the treaty quickly became obsolete: the collapse of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact led to arms reductions in Europe that far surpassed those envisioned in the CFE Treaty. Concentrating on expeditionary warfare, NATO countries (including new member states) professionalised their militaries and disbanded their reserve forces in large numbers. Similarly, Russia reduced the size of its land forces after the 2008 Russo-Georgian War to improve the quality, flexibility, and readiness of those that remained. Like their American counterparts, Russian military forces are now highly mobile, capable of deployments across vast distances in a short time. During several manoeuvres in the last decade, Moscow has proved able to deploy 70,000-150,000 troops of all types to even remote parts of Russia. Hence, the number of troops formally deployed to a specific region hardly mattered; they could be quickly reinforced if necessary.

The treaty’s allocation of inspection rights would have provided a valuable confidence-building measure. However, Russia partially suspended its compliance with the treaty in 2007, before fully suspending implementation of it in 2015, following a sharp decline in its relationship with this West. The resulting loss of inspection rights and transparency has been lopsided: although the West lost its right to inspect facilities in Russia, Moscow is still able to gain intelligence from its Collective Security Treaty Organisation allies’ inspections of military sites in Europe.

The Vienna Document

The Vienna Document on Confidence-Building Measures was meant to augment the CFE Treaty. The document – which was conceived in 1990 and revised in 1992, 1994, 1999, and 2011 – has a wider reach than the treaty, as it covers all OSCE members. Although it is not legally binding, the document requires every OSCE member to file an annual report on the structure, size, equipment, and rough disposition of its conventional armed forces, as well as its exercises, deployments, and other military activities that result in the movement of large numbers of troops.

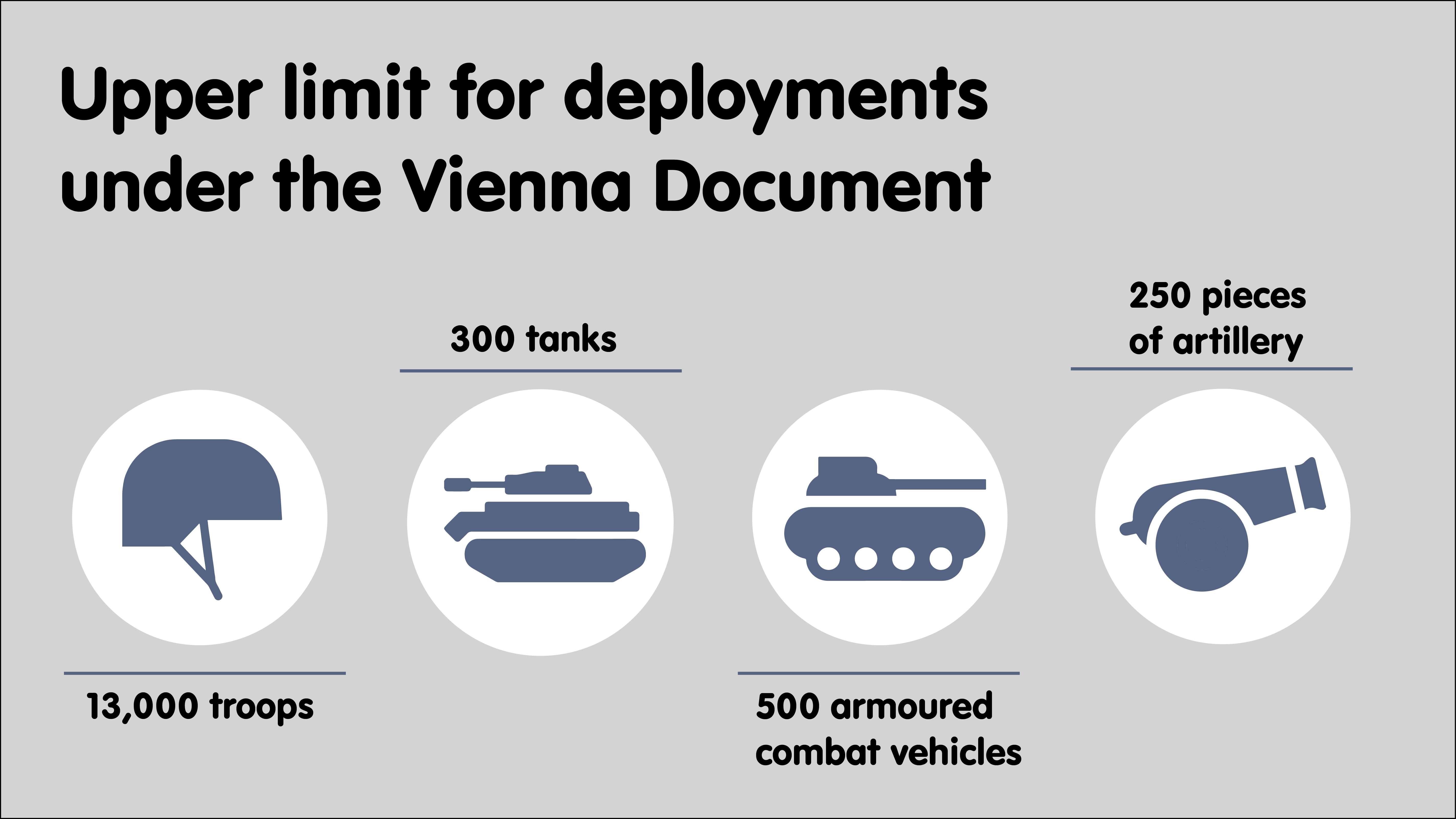

However, there are significant loopholes in the document. Above all, its notification and inspection mechanism does not apply to snap inspections or exercises. Parties to the arrangement are only required to admit inspectors if the total strength of manoeuvring forces exceeds 13,000 troops, 300 tanks, 500 armoured combat vehicles, or 250 pieces of artillery. As with the CFE Treaty, the document applies only to Russia west of the Urals.

Russia uses these loopholes to de facto ignore the Vienna Document. The country formally presents each large-scale exercise west of the Urals as a series of separate smaller initiatives that fall under the threshold for inspections. However, these purportedly separate exercises constitute the various operational phases of a single wargame: a snap inspection, or mobilisation phase; a counter-terrorism exercise, or initiation of conflict through hybrid operations; a main strategic manoeuvre (such as the Zapad and Kavkaz exercises); a combined arms attack to strike the enemy and gain control of territory; parallel manoeuvres (such as those held with the Northern Fleet) practising defensive operations in other theatres to hedge against enemy retaliation; a long-range aviation exercise to interdict the enemy’s reinforcements and conduct deep strikes against its rear areas; and a strategic missile forces exercise to exercise conflict termination through control of nuclear escalation. By compartmentalising manoeuvres in this way, Russia circumvents the Vienna Document to hold politically destabilising exercises close to other nations’ borders.

Some of these exercises have foreshadowed invasions of neighbouring countries. In 2008, Russia used Kavkaz to pre-position troops to strike Georgia; in 2014, it used snap exercises to mobilise its forces for the annexation of Crimea, and conducted “manoeuvres” near Ukraine’s borders that limited the Ukrainian military’s deployments against insurgents in Donbas.

Together, these exercises keep the West guessing as to how many Russian troops operate in a given area, and as to when the Russian military will shift from exercises to preparation for war. As a consequence, the Vienna Document’s confidence-building measures fail to achieve their aim. Since 2011, Moscow has made unrealistic demands to block every attempt to update the document.

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty

Signed in 1987, the INF Treaty forbids the production and possession of any land-based delivery system with a range of 500-5,500km. The agreement does not apply to sea- and air-based delivery systems such as submarine-launched ballistic missiles and air-launched cruise missiles. Only the Soviet Union and the United States have officially signed (and Moscow has accepted Russia’s legal obligations under) the treaty, but Germany, France, and the United Kingdom unilaterally abide by it.

Washington devised the treaty to prevent Moscow from using nuclear blackmail against isolated European states without posing a direct threat to the US homeland. Because intermediate-range nuclear missiles were too powerful to serve as “tactical” or battlefield weapons, the Europeans feared the Soviet Union would use them as a pre-crisis tool to split the alliance. The Soviets only agreed to sign the INF Treaty and dismantle their vast arsenal of intermediate-range nuclear missiles because they feared US deployments of the Pershing II missile in Europe.

The Pershing II’s manoeuvrable, guided re-entry vehicle lent it a precision that was unique among ballistic missiles of the time. Soviet military planners thought this would enable the US to knock out Moscow’s political and military leadership, as well as its key nuclear weapons facilities, with little prior warning – thereby deciding the outcome of a war in its first few minutes. Today, in contrast, Moscow has little to fear from America’s capabilities in this area.

Since the early 2010s, Russia has circumvented the INF Treaty through the deployment of dual-use Kalibr-NK cruise missiles, which have a range of roughly 2,500km, on small corvettes and gunboats. Russia can move these littoral combatants through inland waterways and lakes, placing them beyond the direct sight of the US Navy and making them difficult for NATO to detect. This means that during, for example, an escalating crisis in the Baltic region, Russia could threaten Berlin, Paris, and London using vessels in the port of Kronstadt or the rivers around St Petersburg.

Russia then appeared to fully violate the INF Treaty, mounting the launch tube of a Kalibr-NK cruise missile on a mobile, land-based Iskander launcher. To retain plausible deniability, Moscow argues that the cruise missile fired from these launch tubes has a shorter range than the sea-launched Kalibr. As the Kalibr launch tube can fire several kinds of missile, this might be true. Yet Moscow has not demonstrated how its land-based launcher differs from the naval variant.

Russia also accused the US of having violated the INF treaty first, through the deployment of drones. This argument can be dismissed out of hand, as drones are remotely controlled, unmanned aerial vehicles that, if subject to regulations, would constitute combat aircraft under the CFE Treaty. Russia’s argument that US missile-defence sites in Poland and Romania could harbour Tomahawk cruise missiles is more difficult to dismiss. Indeed, these sites’ Mark 41 Vertical Launch System can fire the Tomahawk, which has a range of around 1,600km. But inspections could easily verify which missile was loaded, while the fact that the sites are stationary makes it near-impossible to conceal any changes to them. The Polish government put inspections and confidence-building measures on the table when negotiating the agreement to host its missile-defence site – only for Russia to reject them as insufficient. Moreover, it seems unlikely that Russian leaders made their accusations against the US sincerely, so why try to prove them wrong?

Reciprocal inspections could reduce mutual distrust and resolve the issue. But they would unveil more about Russia’s capabilities than America’s. For instance, there is no nuclear-capable Tomahawk. And, as Iskander systems are mobile, verifying their deployment and capabilities would mean allowing inspectors to enter multiple currently inaccessible sites. Because these systems are nuclear-capable, such inspections would grant the West some insight into Russia’s non-strategic nuclear capabilities. (Non-strategic weapons are those with a range of less than 5,500km.)

While Russia’s approach to the INF Treaty raises serious compliance issues, Washington’s pending unilateral withdrawal from the agreement will only make matters worse. Firstly, it would allow Russia to use its vast territory to deploy and hide various intermediate-range systems – which could be used to selectively blackmail European states during a crisis, or to launch pre-emptive strikes deep into western Europe during a war. The European Union could be held hostage to Russian escalation control.

Secondly, the collapse of the treaty would spark a debate on countermeasures within NATO that alliance members are ill-prepared to lead. In all western European countries aside from France, the cold war culture of defence has vanished, as has elites’ ability to communicate the procedures, postures, and signalling of nuclear deterrence. Even without a nudge from Kremlin propaganda, most European citizens would strongly resist any new Nachrüstung (literally “catch-up armament” – a term German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt often used to underline the need for NATO to react to the Soviet deployment of SS-20 missiles in the late 1970s). In contrast, eastern European states – particularly Poland – need little encouragement to lobby for the deployment of American nuclear delivery systems on their soil.

Washington’s pending unilateral withdrawal from the INF Treaty will put Europe in a very difficult spot. For many Europeans, the US has cancelled a treaty they see as essential to their security, without seriously attempting to arm-wrestle Russia into compliance. The US made no push to modernise NATO’s integrated air defences in a way that would pose a greater obstacle to Russian cruise missiles. Nor did it consult with its NATO allies. Russia will be free to develop and deploy both the RS-26 Rubesh and the Iskander-K without any treaty constraints, and to threaten European states with them. Meanwhile, the West has no equivalent capability. Thus, the withdrawal is a diplomatic and strategic disaster in the making.

The Open Skies Treaty

Signed in 1992 and implemented a decade later, the Open Skies Treaty allows its signatories to conduct reconnaissance flights in one another’s airspace using unarmed aircraft. Like the CFE Treaty, the agreement includes a quota system that ensures signatories reconnoitre multiple states rather than just one.

Until 2014, the treaty worked rather effectively. However, even this agreement became a casualty of the decline in the relationship between Russia and the West. Moscow used territorial disputes over Crimea, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia to introduce diplomatic hurdles to Open Skies verification flights. Russian leaders argued that, as purportedly independent states, Abkhazia and South Ossetia were not signatories to the deal and were hence off limits. Similarly, they insisted that signatories treat Crimea as Russian territory under the agreement, which would affect Russia’s passive quota. And Russia has restricted the overall length of flights over Kaliningrad to a high altitude and only 500km in distance travelled across the territory, while barring Ukrainian aircraft from flying over Russian territory (Ukrainian observers have been able to get around this by flying missions in Canadian aircraft). In all, Russia’s restrictions have greatly diminished the treaty’s usefulness to Western countries, as there are now strict limits on their flights over some of the areas that concern them most.

The OSCE’s Structured Dialogue and deconfliction

Initiated at a ministerial summit in Hamburg in 2016, the OSCE’s Structured Dialogue is designed to cover mutual security concerns, issues involving the international rules-based order, threat perceptions, and risk-reduction mechanisms. Rather than attempting to create a major new treaty similar to the CFE, the dialogue currently focuses on risk reduction.

It is hard to judge the progress of the initiative – as reflected in the mixed views of it among European officials. Russia seems comfortable with its current position of strength and lack of transparency, while European states are uncomfortable with it. Although the German OSCE chair pushed for compliance with the Vienna Document in 2016, the subsequent Austrian chair did not follow up on this. The moment German pressure eased, Russian complacency over the document returned.

Meanwhile, the management of incidents and prevention of dangerous encounters of NATO and Russian aeroplanes and ships over international waters has become another urgent matter. So far, 11 NATO members have signed agreements with Russia. However, these deals have had mixed results, as Russia’s willingness to comply with them depends on the power of the co-signatory and the perceived consequences of breaking the agreement. Unsurprisingly, small countries within the alliance would like NATO, especially the supreme allied commander Europe, to have a major role in deconfliction arrangements with Russia. In contrast, large member states prefer to work through bilateral forums and are reluctant to create new, rival deconfliction mechanisms. Moscow only became interested in deconfliction after Turkey shot down a Russian Su-24 fighter-bomber in 2015. And, even then, it is only willing to sincerely participate in deconfliction measures when Russian military commanders believe that non-compliance would have negative consequences for them.

Russia’s perception of threat

During the latter stages of the cold war, Moscow was quite satisfied with its global position. As the leader of the “second world”, the Soviet Union enjoyed undisputed command of its dominion, had emerged victorious from the last global military confrontation, and competed with the US on equal terms in every region of the world and on every major international issue. Furthermore, many Soviet leaders believed that they faced little threat domestically, trusting the KGB to deal with dissidents and opposition movements. Yet Soviet military planners feared NATO’s technological and organisational superiority.

The advent of the digital revolution, the emergence of increasingly advanced weapons systems, and the adoption of ever more flexible operational concepts – especially the US military’s Air-Land Battle (designed to defeat the Warsaw Pact in a flexible manoeuvre war) – created concern that the Soviet Union would fall behind militarily or would be otherwise unable to keep pace with the West. All these factors contributed to the Soviets’ worries that US deployments of intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe foreshadowed a decapitation strike. Arms-control agreements provided Moscow with a way out of an arms race that it could not win at a reasonable cost, paving the way for the CFE and INF treaties.

While the late-era Soviet Union was a status quo power, modern-day Russia is revisionist. Moscow wants to renegotiate the post-1991 European order, which it perceives as unsatisfactory. Russia aims to regain its “sphere of influence”, strengthen its global position, and receive greater recognition from the West. The Kremlin has made demands to this effect in many different ways – most prominently, in its proposal for a new pan-European security treaty in 2008. The country also uses military pressure to pursue its revisionist foreign-policy goals.

But, contrary to Russian propaganda about NATO as an enemy at the gates, Russia does not worry about a conventional Western military invasion. The Kremlin is more concerned about internal threats. Russian leaders suspect that the West orchestrated events such as the colour revolutions using their intelligence services, non-governmental organisations, and soft power. Strikingly, Russian military literature defines hybrid warfare with reference to perceived Western, especially American, operations in Georgia (2003), Ukraine (2004 and 2013), and the Middle East (2011). Russia perceives itself as having merely adapted to the West’s new way of war.[1]

Russian President Vladimir Putin views Western leaders, particularly Hillary Clinton, as responsible for the opposition protests that followed Russia’s 2011 election. Indeed, this perception may have been a primary motive for Russian interference in the 2016 US election. Putin’s viewpoint mirrors that of Soviet leaders who blamed the West for revolts in East Berlin (1953), Hungary (1956), Czechoslovakia (1968), and Poland (1980-1981).

Russia’s current military doctrine also identifies destabilisation from within as a key security threat. Accordingly, the country’s military and its paramilitary organisations both engage in counter-insurgency and counter-protest manoeuvres. Many of these manoeuvres are closely coordinated with those for rehearsing war with NATO – suggesting that, for Moscow, these issues are related.

In this context, it is easy to see why arms-control regimes the Soviet Union supported have fallen out of favour in Moscow. The Russian government sees the Helsinki Accords’ and Paris Charter’s emphasis on democracy and human rights as conducive to Western subversion – and, thus, as biased in favour of the West. To Moscow, peace based on the Paris Charter is war on Western terms. So, could any arms-control agreement currently satisfy both Russia and the West, given that no European state would put its citizens’ or non-governmental organisations’ freedom of expression on the table in arms-control negotiations with Moscow?

Although Russia has made a sizeable investment in political subversion and information warfare, its propaganda outlets are far from influential in the West and it has only been able to cultivate close ties with the extremist fringes of the European party system. Moscow’s most effective tool for offsetting its disadvantages in soft power is the ability to project military force in its immediate neighbourhood. To induce fear of military retaliation in the minds of European policymakers and thereby deter perceived Western meddling in its domestic affairs, Russia needs to acquire offensive options against the West. Hence, the Russian military tries to exploit the West’s various weaknesses – be they exposed territory and communications links, vulnerable critical infrastructure, political indecisiveness, or a lack of time and preparedness – to establish a military advantage.

Therefore, when the Kremlin denounces NATO as a “threat” in Russia’s neighbourhood, it is referring to the alliance’s denial of Russian offensive options. If the Russian military loses some offensive options, Moscow reasons, it will be unable to deter Western subversion at home.

Russian military thinking – Tsarist, Soviet, and contemporary – has always focused on offence. Russia should not wait to absorb an offensive; rather, it should strike first with an operation on its terms and drag the war into enemy territory. The country’s traumatic experiences with the 1812 French invasion and 1941 Nazi invasion are widely cited as reasons for this mindset (although other countries in Europe have been invaded much more often, and with equal or more dramatic consequences for their populations).

Russian military thinkers emphasise their belief that, while the armed forces primarily aim to defend Russia’s strategic interests, they should always seek to go on the offensive.[2] Moreover, Russia’s defensive strategic interests usually centre on an ability to dominate and intimidate the country’s immediate neighbourhood, not the defence of its borders. In any war, Russian military leaders seek to go on the offensive as soon as possible. What Russian military literature calls deterrence, the West calls coercion: not only dissuading the opponent from hostile behaviour towards Russia, but also pressuring others to pay respect to non-defensive Russian interests.

In Russian military thinking, the line between war and peace is as blurred – or non-existent – as that between offence and defence. The Russian security establishment at large subscribes to a rather robust interpretation of Carl von Clausewitz’s maxim that war is an armed struggle between two opponents trying to impose their will on each other. Hence, war is only a violent eruption of a coercive contest that also takes place during peacetime.

Russian military coercion (as Western thinkers describe it) forms part of a comprehensive effort that also involves economic, political, religious, ideological, psychological, and cultural coercion.[3] In this approach, wars are fought not just by regular military forces but also entities such as corrupted or coerced political actors; citizens’ movements and non-governmental organisations; media outlets; private businesses; financial organisations; religious groups and institutions; criminal gangs; irregular forces; rebel groups; international terrorist networks; mercenaries; private military companies; intelligence agencies; covert special operations forces; and peacekeepers.

For Moscow, criticism of the Russian government from any of these entities clearly signals that they are part of a Western plot. In essence, Russia perceives itself to be at war with the West, meaning that its actions are a justified response to Western aggression. The most high-profile aspect of this response is Russia’s information warfare campaign against the West.

Another key aspect of Russia’s approach to dealing with the West is its projection of military power and its intimidation through latent military force. Military operations against the West, as rehearsed in Zapad exercises, rely on speed and surprise rather than brute force and numbers. They are designed to deliver a strategic shock to the West, stun its political systems, and establish facts on the ground before the West can bring its superior military power to bear. Judging by its mobilisation and deployment on Ukraine’s borders, the Russian military can deploy a corps-sized formation – comprising one airborne division; several regiments of special forces; electronic-warfare troops; artillery; air-defence systems; some armoured formations, up to brigade size; around three or four fighter wings; and littoral naval assets – within seven days, and an armoured manoeuvre army roughly three times the size within a month or so.

This is considerably faster than NATO could react. The alliance’s Very High Readiness Joint Task Force – comprising roughly 5,000 troops – is ready to deploy within five days, while the 45,000-strong NATO Response Force is ready to deploy within 30 days. The deployment process would take more than a week, depending on where the forces were generated. American reinforcements would have to be airlifted across the Atlantic, a procedure that takes several months. European armies would be too small, too ill-equipped, or (like the Bundeswehr) in too dismal a state of readiness to decisively change the balance of military power.

A lack of nuclear transparency

Russia inherited a large stockpile of tactical nuclear warheads from the Soviet Union – most of which are now outdated, and have probably been phased out along with their delivery systems. Due to a lack of notification mechanisms, one can only make crude estimates about the extent to which this occurred and the exact disposition of remaining warheads and delivery systems.

This lack of transparency fits with the Russian military’s nebulous nuclear doctrine. The only official remark on nuclear weapons in the doctrine is: “Russia reserves the right to use nuclear weapons in response to a use of nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction against her and (or) her allies, and in a case of an aggression against her with conventional weapons that would put in danger the very existence of the state.” This rather orthodox statement contrasts with the bellicose rhetoric Russian officials sometimes employ – such as their threats to launch nuclear attacks on Poland and Denmark if these countries hosted US missile-defence facilities (threats made in 2008 and 2009 respectively). Russia’s definition of “the existence of the state” is also unclear, as Kaliningrad and Russian-occupied Crimea act as forward-basing areas that could be used to interdict NATO reinforcements. These areas could present an anti-access/area-denial challenge for NATO if it had to repel a Russian attack on, for example, the Baltic countries.

Western analysts have long debated whether Russia would use a pre-emptive first strike to “de-escalate” a war with the West, ending the conflict on terms favourable to Moscow. In recent years, Western commentators have raised doubts about this apparent de-escalatory doctrine (not least because some of them initially misunderstood the concept). During the cold war, the Soviets’ decisions on nuclear weapons use rested with the State Committee for Defence. However, nuclear planning – covering targeting, allocation of means, orders, and other areas – was the responsibility of the general staff; theatre commands; Soviet operational commands and naval fleets; and other operational commands, including those of Warsaw Pact armies. The allocation of nuclear means and the responsibility for nuclear targeting varied between these commands, reflecting different operational and tactical requirements, challenges, and priorities of these actors’ campaigns or battle plans. The multitude of commands involved in nuclear warfare required a relatively high degree of formalisation, along with a doctrine that gave them a shared understanding of such warfare.

In contemporary Russia, the situation is entirely different. After engaging in a process of reform and modernisation, the Russian armed forces decreased their reliance on nuclear weapons for firepower augmentation on the battlefield. Since 2010, no Russian exercise has rehearsed the use of tactical nuclear weapons in the manner of the Warsaw Pact. Today, all Russian nuclear weapons are “strategic” in the sense that Russian leaders decide whether to use, or threaten to use, them based solely on their capacity to fundamentally alter the stakes in a conflict – to compartmentalise or decide a war by either deterring an opponent’s allies from committing forces or limiting the alliance’s reaction.

As it stands, Putin is the only person who can take such a decision. Hence, there is no need to formalise a clear nuclear doctrine, nor to foster a common understanding on nuclear warfare among his subordinates. For a nuclear power, Russia is striking in its lack of a publicly available document on nuclear warfare and its strategic community’s lack of shared understanding and perception of the use of nuclear weapons. As Moscow seeks to maximise European governments’ insecurity and widen splits within the alliance, transparency would only harm its interests.

Still, the Russian military prepares for all eventualities. It employs dual-use missiles and aircraft in all major manoeuvres, leaving spectators to guess as to their actual payload. The military concludes each manoeuvre season with an exercise involving the strategic missile forces, training them for escalation dominance in everything from limited short-range strikes to full-scale nuclear retaliation. In August 2014, when Russian mechanised formations began incursions into Donbas to decide the Battle of Ilovaisk, Putin stressed that “Russia was a nuclear power not to be messed with”. During the peak of the Crimea crisis in March that year, Russia conducted high-profile nuclear exercises.

While Russia announced the exercise in advance, Putin could have cancelled or postponed it if he wanted to send a different signal about his country’s willingness to use nuclear weapons. Moscow’s drive for nuclear escalation dominance, combined with its military emphasis on pre-emptive strikes and offence, amounts to a de facto concept of nuclear de-escalation. Again, Russia’s primary goal is to keep the West guessing about its intentions, as well as its threshold for nuclear-weapons use, to induce fear.

Western countries tried to place non-strategic nuclear weapons on the arms-control agenda before 2014, with very limited success. Russia usually put forward demands that it knew they could hardly accept – such as to withdraw all US nuclear weapons and missile-defence assets from Europe. Moscow did so because it maintains a competitive advantage in this area. Russia’s short-range ballistic missiles such as the Tochka and the Iskander, as well as its cruise missiles such as the Kh-55 and the Kalibr-3K14, are formidable weapons that can strike targets even where the enemy has air superiority.

In contrast, the B-61 on which NATO relies is a gravity bomb that can only be employed if the aircraft that carry them can roam freely over the target area. Regardless of how the West perceives Russia’s attitude towards employing tactical nuclear weapons, Moscow can use them to make credible threats against all NATO states but the alliance cannot respond in kind. This central dilemma makes it extremely difficult to force Russia to comply with the INF Treaty or arms-control agreements on tactical nuclear weapons.

The fog of peace

From a Western perspective, Russia’s aggressive military posture, intellectual inclination towards pre-emptive and offensive warfare, and repeated miscalculations about European behaviour provide a strong rationale for arms control and confidence-building measures. However, Russia appears to have little desire to make its relationship with the West more predictable.

Moscow’s withdrawal from the CFE Treaty and selective implementation of other arms-control agreements – particularly the Vienna Document and the Open Skies Treaty – support its overall goal of gaining influence through fear in its neighbourhood. Reducing transparency, predictability, and confidence forces Russia’s neighbours to worry about what it has in mind, and whether it might engage in military retaliation to perceived slights.

On an operational level, a Russian pre-emptive military strike against a European country would rely on surprise and speed. For instance, all allied military forces in the three Baltic states – including those within the Enhanced Forward Presence – amounts to 19 standing battalions.[4] Russia has based 40 battalions of combat and combat-support troops close to its border with these countries. Russian troops could win a quick, decisive victory by surprising local forces that had not moved into defensive positions. And, even if these forces did move into defensive positions in time, Russia would still win due to its air superiority, albeit at a higher cost. Yet, if local forces mobilised reserves and NATO pre-deployed additional troops and air, and air-defence forces, Russia could well face defeat.

These considerations help explain why Russia has been unwilling to enter talks on improving the Vienna Document or to engage in substantive confidence-building measures. So far, deconfliction and incident-prevention are the only areas in which the Russian military has been willing to engage with the West. While this coordination is important, it falls short of Western expectations. Crucially, Russia’s lack of interest in transparency and predictability is structural, not temporary. The country’s secretive and ambiguous approach results not from distrust of the West nor diplomatic brinkmanship, but from a strategy for preserving Russian military power on NATO’s eastern flank. There is no form of dialogue or other means of engagement that will change this fact. In other words, Russian officials understand the West’s desire for greater transparency – which is exactly why they do not provide it.

Nonetheless, Moscow is willing to talk about arms control when it affects NATO’s force posture on the eastern flank in a way that preserves the Russian military advantage there. For example, the Kremlin would be happy to limit the alliance presence in the region. This would enhance Russian political leverage by dividing NATO territory into a defensible area and what was effectively an indefensible buffer zone. In the event of war, rapidly deployed Russian forces could isolate or circumvent small-scale NATO or local contingents (as happened to Ukrainian forces in Crimea), perhaps even avoiding a firefight.

Equally, Russian diplomats have been receptive to the idea of “zones of limited troop deployments” that some German experts aired in 2016 (as Frank-Walter Steinmeier, then the German foreign minister, attempted to rejuvenate conventional arms control in Europe). Given the high mobility of modern militaries, such arrangements would benefit the aggressor. Depending on their size, such zones could increase the time it would take the defending side to call in reinforcements. Poor railway connectivity to several parts of the eastern flank (including Baltic countries, Romania, and Bulgaria), a lack of airports through which to deploy troops, and natural obstacles such as the Baltic Sea already prolong this process, giving Russia an operational advantage. In contrast, Russia has many railways that reach to its western border, and it can deploy its forces to the theatre much more quickly. Were it willing to break its commitments under the German proposal, Moscow would have gained yet another operational advantage.

Russia also has an interest in arms-control agreements that would allow it to hedge against advanced Western, particularly American, technology. At the July 2018 US-Russia summit in Helsinki, Putin pushed for a strategic arms control agreement with Washington. He suggested extending New START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty), as well as subjecting missile-defence facilities to arms control and banning space-based weapons. While such weapons are still in their infancy (however much they may capture the imagination of the US Congress), Russia lacks the technical and economic capacity to engage in an arms race involving them. As Moscow has drastically scaled down its space programmes since the collapse of the Soviet Union, such systems would be prohibitively expensive to develop from scratch. Abolishing them in an arms-control agreement would be the cheapest way for Russia to maintain an image of strategic parity with the US. The same is true for missile defence, an area in which American research and development are peerless.

Russia has a similar rationale for extending New START. Despite prioritising the modernisation of its strategic nuclear delivery systems, Moscow needs to find replacements for the ageing R-36M and UR-100 missiles, which carry the bulk of the Russian military’s deployed land-based strategic nuclear warheads. Russia’s Project 667 Delta-class submarines are also approaching obsolescence, as are its Tu-160 and Tu-95 strategic bombers. All these delivery systems and their warheads were designed and built during the Soviet era. It appears that Russia’s new submarines and its submarine-launched, silo-based, and road-mobile missiles will replace equipment that is being phased out without increasing the overall number of weapons.

Were New START to collapse, Russia’s nuclear forces could muster around 2,400 strategic nuclear warheads if they loaded all missiles to maximum capacity and recommissioned all test beds as fully operational systems. If US nuclear forces were to do the same, they could muster around 4,600 strategic nuclear warheads. For Moscow, losing New START would mean losing strategic parity with Washington. Thus, Putin is trying to sustain the agreement – quietly, and without the usual barrage of propaganda and insults.

Moscow’s rationale on arms-control agreements is straightforward: if side-stepping obligations under such deals will empower the Russian military, Russia will find excuses and political conditionalities that allow it to do so. In contrast, Moscow is open to arms-control agreements if they limit Western military advantages, prevent the technological gap between Russia and the West from growing, or otherwise help Russia remain a great power. This logic creates an opportunity for the West. If military utility dominates Moscow’s arms-control policy, Western countries can influence the policy to a much greater extent than they first thought – by changing the military balance of power.

Since 2007, Russia’s activities have been the key driver of militarisation in eastern Europe. Moscow increased the scope and technical sophistication of troop and weapons-system deployments in the Western Military District and the Southern Military District. The West has only reacted to these developments since 2014 and, even then, its counter-deployments have been largely symbolic. The main rationale for Western restraint was to avoid provoking Russia and thereby precipitating an arms race. Yet there has been an arms race nonetheless – one conducted purely on Russia’s terms.

A united West?

One of the biggest problems Europeans face is that they can hardly pursue arms control on their own. In the past, the US was essential to these efforts for two reasons. Firstly, Moscow considered Washington to be its sole important opponent. For the Kremlin, the struggle over the post-cold war order may take place in Europe, but it is a struggle with the US rather than European states. Eager for concessions from the White House, the Kremlin would only sign an arms-control agreement if the US president also did so. Yet, under Donald Trump, the US is no longer able to use its political authority to unify the West through multiple rounds of disputes and clashes of interest.

Moreover, it is hard to tell where the Trump administration’s interests in arms control lie. Trump refuses to criticise Putin and pushes for a “deal” with Russia – whatever this may entail – while expressing little interest in arms control. Indeed, he wants to expand America’s missile-defence programmes and create a space force. For Europeans, it is unclear how the US president would resolve the inherent contradictions in his policies, and under what circumstances he would trade off one objective for another.

Then there are modern-day conservative Republicans, who in most circumstances perceive arms control as an unnecessary hindrance on American industrial creativity, military power, and global pre-eminence. Trump’s push for a space force is the latest manifestation of American exceptionalism. If it can field a capable space force, the US can deny other powers access to space and hence maintain its military pre-eminence – or so its proponents argue.

In any case, Republicans’ belief in the power of American innovation could persuade them to ignore arms-control treaties Europeans regard as essential to their security, creating friction in the transatlantic relationship. And American military planners may be far more interested in the US-Chinese balance of power than arms control in Europe. The US threat to unilaterally withdraw from the INF Treaty is an example of this.

Then there is Congress, which has developed an interest in Russia’s compliance with arms-control treaties. Congress has already threatened to end US ratification of New START if Moscow abandons the INF Treaty. It believes Russia should be made to honour previous arms-control agreements before the US government negotiates new ones. This approach is effective in that it avoids rewarding Russian aggression and brinkmanship. Nonetheless, the chances of returning to the old order are remote, and many of the provisions of existing arms-control agreements are outdated. Future arms-control treaties may be shaped not by traditional establishment forces, but radicals close to Trump or Putinversteher (Putin apologists) in Europe – even if Russian meddling in the 2016 US presidential election has led American leaders across the political spectrum to support the containment of Russia.

Like the political establishment in Washington, most European states approach arms control from the perspective of a legalistic status quo powers. This reflects their desire to maintain the existing order and resist Russian revisionism. But, aside from signalling intent, their current approach will yield little. Moscow is unwilling to subscribe to anything short of an agreement that formalises its current military advantage on NATO’s eastern flank. Although Washington could live with a further collapse in arms-control agreements (particularly the INF Treaty), this would strain European cohesion. Given that political tension is already high due to Brexit, the migration crisis, and the eurozone debt crisis, Europe can ill afford a rerun of the 1977-1982 Euromissile Crisis.

A sense of vulnerability has prompted NATO, as well as several European politicians, to support a policy that pressures Russia to return to confidence-building measures, inspections, and INF compliance. This had long been the right way forward – but it might now be too late. Europeans should have raised their voices when US diplomats working under the Obama administration highlighted Russian INF Treaty violations. It remains unclear how Europeans would be willing to pressure Russia to seriously commit to arms-control negotiations.

As the debate on NATO enlargement and missile defence unfolds, Europe will remain as vulnerable politically as it is militarily. Russia will skilfully use complex technical arms-control issues to delegitimise European defence, create a pretext for aggressive action, and disrupt political processes in Europe. For the EU, developing an arms-control agenda is as much about the ongoing psychological and information confrontation with Russia as it is about security measures. But Europeans are still divided about how to deal with Russia on arms control.

Some states – including Austria and Italy – perceive Russia’s desire to maintain influence in the post-Soviet sphere as legitimate and, therefore, sympathise with its declared security concerns. Viewing their interests in Russia primarily through an economic lens, these countries would like to resolve security disputes and resume a normal trade relationship with Russia as soon as possible. Thus, they are prone to endorsing purported compromises that would entrench the Russian military advantage.

Most European states, particularly Germany and France, reject Russia’s revisionist goals in eastern Europe but do not view them as a direct threat. Because most European political leaders are preoccupied with other issues, bureaucratic politics dominates arms-control discussions. They do not want to push for new arms-control policies, fearing that this would begin another daunting domestic policy fight.

In contrast, leaders in states on NATO’s eastern flank such as Poland and Romania, along with non-NATO Sweden and Finland, do see Russia as a direct threat. As a result, they want to improve their security before discussing arms control. The UK, traditionally a voice of reason on arms control, may have deterrence and diplomatic capacity, but it is currently so preoccupied with Brexit that it has no energy for a new arms-control initiative.

A way forward?

EU member states need a shared approach to arms control, as national initiatives – such as Steinmeier’s effort in 2016 and the Polish push to improve the Vienna Document the previous year – have failed due to a lack of widespread support. Although it is hard to believe that Moscow will seriously discuss arms control any time soon, Europeans do not have to accept the threat from Russian unpredictability as an unchanging fact. Learning from NATO’s 1979 Double-Track Decision, they should combine an offer to talk about arms control with a serious attempt at rearmament. Moscow will only agree to a new arms-control treaty if it faces the prospect of an arms race it cannot win.

Similarly, if Europe – or the West more broadly – significantly increased the scope, scale, tempo, and technical prowess of its military presence on NATO’s eastern flank, Russia would be forced to re-evaluate its hardline stance. However, to achieve this, European states would have to improve the readiness, capability, and deployability of their armed forces; make these improvements visible to Russia (through deployments, exercises, and other initiatives); and agree on an arms-control agenda that provided sufficient predictability, security, and crisis stability. All three steps would be difficult.

Improving European capabilities

In improving its military capabilities to repel Russian aggression, Europe would need to engage in rearmament. However, rearmament is only one part of a broader effort – and not even the most important part. Above all, Europeans should enhance their militaries’ combat readiness and capacity to quickly conduct large-scale, sustainable deployments to eastern Europe. Qualitatively, most western European armies are well equipped to take on Russian forces. But they lack readiness and are positioned too far away from any potential theatre of war, meaning that it would take too long to deploy them in a crisis. It would be beneficial to pre-position more forces in the east, alongside the Enhanced Forward Presence. Nonetheless, because the alliance’s eastern flank is more than 2,000km long, strategic mobility is a must. There always will be weak spots that only highly mobile forces can reach in time.

Furthermore, there are capability gaps Europe must address to successfully deter Russia. These gaps persist above all in: electronic intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, which is required to gather information on Russia’s rear areas; the movement of operational reserves; combat engineering; land forces’ fire-support capabilities; air- and missile-defence assets (to protect key logistical infrastructure and junctions from Russian deep-strike capabilities); and electronic-warfare capabilities and anti-radiation weapons (to counter Russian air-defence and jamming equipment).

Furthermore, Europe should consider efforts to increase technological pressure on Moscow, perhaps through the development of systems that disrupt Russia’s operational planning, increase the sense of insecurity among its decision-makers, and force its military planners to question their basic assumptions. This approach would effectively mirror Russia’s development of deep-strike capabilities – working on the premise that the more an opponent struggles to predict the consequences of military action, the more it will refrain from taking military risks. The initiative could cover space-observation and tracking systems, exoatmospheric interceptors, stealthy autonomous deep-strike drones and hypersonic cruise missiles, and offensive cyber capabilities. Technologically, Europe is in a relatively good position to develop such capabilities.

Could European rearmament also tackle the imbalance in tactical nuclear forces? It is likely that only America’s envisioned deployment of submarine-launched cruise missiles would draw Russia’s attention to the issue. But, in theory, Europe could address the imbalance. Today, the only credible tactical nuclear delivery system in the Western arsenal is the French ASMP-A – an air-launched cruise missile with a range of around 300km. With a top speed of Mach 3 and a relatively small radar cross-section, it is more survivable than manned aircraft. The French concept of using “pre-strategic” nuclear weapons for signalling and escalation control would be useful in dealing with threats from comparable Russian systems. However, French nuclear weapons exist solely to protect France. And, given the current rifts within Europe, there is little to suggest that French elites would support the Europeanisation of the country’s nuclear policy through formal commitments, sharing agreements, or other arrangements.

Still, Europe can counter Russian ambiguity even without a formal agreement. If the French exercised their nuclear-capable systems in a wider manoeuvre with European allies, this could affect Moscow’s calculations. And it would likely do so without having a significant effect on French domestic politics. Moreover, if the successor to the ASMP-A was conceived as a dual-use system, current EU defence cooperation programmes could assist with the development of the conventional version of the missile and share it among allies. In a crisis, this could enhance flexibility of Western countries’ force posture and decrease Russia’s ability to anticipate – and, hence, pre-empt – European operations. One should not underestimate European ingenuity and technological skill in creating a version of the weapon that could defeat Russia’s advanced air defences – if only European governments would commit to the project.

Deterrence and signalling

Improvements in European military capabilities will only be effective if Moscow believes they could be used against Russian forces. Europe needs to demonstrate that it can defend its borders, and to signal to Moscow how it would react to offensive action. Since 2014, NATO has strengthened its manoeuvring and signalling activities – usually under US leadership. For instance, the Saber Strike annual manoeuvre rehearses the deployment of reinforcements in Baltic countries. The largest such exercise, conducted in 2018, involved 18,000 troops and rehearsed the defence of the Suwalki Gap. The creators of Polish exercise Anaconda 2016, involving around 31,000 troops, initially intended for it to be a NATO initiative, but there was no consensus within the alliance for this. (Steinmeier raised particularly strong objections to the exercise.) European leaders should avoid such open disagreement over deterrence issues in future, lest Russia believe there is a split within the alliance that it could exploit in a crisis.

They should also address shortfalls in European militaries’ force generation and rapid reaction. In comparison to Russian exercises, NATO manoeuvres have involved relatively small numbers of troops, have been announced much earlier on, and have required longer preparations. Although the West will have made a positive step in exercising a complete NATO Response Force for the first time in the forthcoming Trident Juncture 18, the initiative will have been prepared months in advance. In a crisis, there is much less time to react. Like Russia, the alliance should conduct snap exercises to test troops’ readiness. Equally, Europeans should rehearse large-scale troop deployments on the eastern flank.

During the cold war, NATO held annual REFORGER (Return of Forces to Germany) exercises. These drills involved the mobilisation of US reserves, transatlantic convoying and air transport, and the mobilisation and deployment of other NATO allies to the West German border. Aside from their training role, these initiatives signalled to the Soviet Union that a surprise attack would be futile. The alliance should take the same approach to modern-day eastern Europe.

The pitfalls of new arms control arrangements

Even if Europeans were to address all the military problems discussed above, they would still be divided over how to create new arms control arrangements. Their differences are such that it is probably quicker to list what they should not negotiate rather than what they should. Building a new European security order from the ground up is charming as an intellectual pursuit but, in reality, it is a non-starter. Apart from anything else, such an order would have to gain the approval of all 56 OSCE members – among which there is no useful common denominator.

Plans for introducing regional or zonal troop limits along the NATO-Russian frontier are also impractical. These arrangements would only benefit an aggressor, which would deploy mobile forces while its opponent was still grappling with the unfolding situation and debating whether to renounce the agreement due to the violation. Thus, such limits would reinforce Russia’s military advantage, aligning with its doctrine of pre-emptive offensive action.

Limits on future military capabilities – especially cyber and automated weapon systems – would be desirable but impossible to implement. The rapid development of computers, robotics, and micro-mechanics will have a profound impact on military conflict and deterrence. But it is unclear which technical characteristics and capabilities will be decisive in future wars – and how they will be decisive. Hence, it is unfeasible to set technical and numerical limitations that will make sense in the future.

Although it is unclear how developments in weapons technology will reshape warfare, states may still be able to establish norms on their accountability and responsibilities in cyber space. European and Russian officials generally worry about the nature of these capabilities rather than the numbers in which they will be deployed. Given that robotic and autonomous weapons systems are in their infancy, it is impractical to place quantitative or qualitative restrictions on them at this stage. Yet it is important to regulate these capabilities to some extent, particularly in setting norms on human decision-making in the use of autonomous weapons.

Indeed, future arms-control arrangements should focus on behaviour rather than weapons systems. Instead of establishing disengagement zones that limit troop deployments, states could improve stability through increased transparency in border areas, agreeing to announce all manoeuvres and other troop movements there in advance. Governments could still organise defensive pre-deployments or reinforcements within the limits of the treaty, preventing eastern NATO states from becoming de facto buffer zones. A code of conduct on the operation of air and maritime systems in international territory – to prevent incidents and unwanted confrontation between the West and Russia – would complement this approach.

As space travel and satellite imaging have become considerably cheaper since the conclusion of the Open Skies Treaty, signatory states could establish a commonly funded daytime imaging service as a confidence-building measure that replaces inspection flights. And they could do so affordably: commercial satellite technology can record images at the maximum resolution permitted under the Open Skies Treaty. This measure would be much more resilient to individual states’ misbehaviour and restrictive measures.

It would be difficult to abolish tactical nuclear weapons, as regional mutual nuclear deterrence between resurgent new nuclear states and allies would require at least a limited arsenal of sub-strategic weapons. The US, Russia, the UK, France, China, and newer nuclear powers have been unable to agree on a new arms-control treaty. But, by limiting the numbers of non-strategic warheads in Europe and establishing confidence-building measures, the West and Russia could decrease the likelihood that they will misread each other. To verify compliance with arrangements such as the INF Treaty, the sides could set up a permanent joint commission that would inspect controversial sites and military units.

These measures would improve stability and create an equilibrium between NATO states and Russia, reducing the chances of accidental escalation. Although they would not return Europe to the general détente of the early 1990s – which would require, above all, settlement of the frozen and active conflicts on the continent – they would help stabilise an increasingly unsettled security environment.

Nonetheless, NATO states and Russia will only agree on new arms-control measures if there is a significant shift in the military balance. The alliance needs to rearm on its eastern flank and deprive Moscow of the offensive options it retains. If it prevents Moscow from making gains from latent threats, arms control will reduce the costs of the ongoing stand-off for the West. To persuade European citizens to support rearmament, European politicians need to devise substantive arms-control proposals that act as desirable, stable goals of the process. Hence, arms control and rearmament are not mutually exclusive; they depend on each other. European states should pursue both tracks simultaneously.

This two-pronged effort will only be effective if it is well coordinated. Were European leaders to attempt to rearm without first devising viable arms-control proposals, domestic opposition in western Europe would halt the process. Conversely, if they rearmed half-heartedly to begin arms-control discussions as soon as possible, Russia would use this as an opportunity to entrench its military advantage on its western flank. Europe should avoid both traps.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gustav Gressel is a Senior Policy Fellow on the Wider Europe Programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR). Before joining the ECFR he worked as a desk officer for international security policy and strategy in the Bureau for Security Policy in the Austrian Ministry of Defence (MoD) from 2006 to 2014 and as a research fellow of the Commissioner for Strategic Studies in the Austrian MoD from 2003 to 2006. He also was committed as research fellow in the International Institute for Liberal Politics in Vienna. Before his academic career he served five years in the Austrian Armed Forces. Gressel earned a PhD in Strategic Studies at the Faculty of Military Sciences at the National University of Public Service, Budapest and a Masters Degree in political science at Salzburg University. He is author of numerous publications regarding security policy and strategic affairs and a frequent commentator of international affairs.

FOOTNOTES

[1] See: VA Kiselyov and IN Vorobyov, “Hybrid Operations: A New Type of Warfare”, Military Thought, vol. 24, no. 2, 2015, pp. 28-36; DA Pavlov, AN Belsky, and OV Klimenko, “Military Security of the Russian Federation: How It Can Be Maintained Today”, Military Thought, no. 1, vol. 24, 2015, pp. 17-25.

[2] I Popov and M Khamzatov, “Voina budushchego: kontseptualnye osnovy i prakticheskie vyvody, ocherki strategicheskoi mysli”, Kuchkovo Pole, 2016, p. 17 (hereafter, Popov and Khamzatov, “Voina budushchego”).

[3] Popov and Khamzatov, “Voina budushchego”, p. 18; SG Chekinov and SA Bogdanov, “The Art of War in the Early 21st Century: Issues and Opinions”, Military Thought, no. 1, vol. 24, 2015, pp. 26-38.

[4] International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2018 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), pp. 98, 200.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.