Reform from crisis: How Tunisia can use covid-19 as an opportunity

Summary

- Tunisia’s 2019 elections produced a vote against the establishment and a fragmented political landscape in which it was challenging to form a government.

- Parliament is deeply divided and lacks a clear foundation for stable and efficient policymaking, while the new president has neither political experience nor a party to implement his agenda.

- The 2019 elections may have finally ended the transactional power-sharing agreement forged by Ennahda and representatives of the old regime, which long ignored major socio-economic challenges.

- The government must build on its successful response to the covid-19 pandemic to create a compromise that shares the burden of economic reform between major political actors and interest groups.

- If it fails to do so, the resulting rise in economic and social tension could empower anti-democratic forces and destabilise Tunisia.

- The European Union should actively help the Tunisian government take the path of reform by launching a strategic dialogue to rethink their priorities and identify their common interests.

Introduction

Tunisia’s most recent presidential and parliamentary elections, held in September and October 2019, were major milestones in its democratisation process. The rise of anti-party figures and radical movements reminded Tunisia’s political elites that deep socio-economic inequality and corruption continue to destabilise the country’s fragile political system. The fragmentation of the political landscape shows that the consensus in place since 2014 – which created stability by ending political polarisation – has reached its limits. The consensus eventually led many voters to reject elites’ perpetuation of the socio-economic and cultural system of the Ben Ali regime. This process came to define the 2019 elections, which saw a sharp decline in support for Tunisia’s largest parties and the emergence of poorly articulated political movements – some of which made radical demands on issues such as morality in public life, as well as sovereignty.

Accordingly, the elections reordered the political landscape in important ways. The fragmentation of secular forces, combined with Ennahda’s electoral losses, put an end to the transactional compromises that had shaped Tunisia’s politics in the preceding five years. The crisis that engulfed parties unable to meet the people’s demands, and the interplay of old and new political divisions, has created an environment in which uncertainty prevails. A January 2020 no-confidence vote in Islamist-backed prime minister-designate Habib Jemli, and delays in forming an administration led by Elyes Fakhfakh, demonstrated the difficulty of forming the kind of effective and stable government needed to address the socio-economic problems that have plagued Tunisia since 2011.

Covid-19 has created a new dynamic within this transition period. The pandemic exacerbates long-term challenges such as an economic crisis, social and regional inequality, inadequate healthcare, and political instability in ways that will test the capacity and unity of the ruling coalition.

However, covid-19 could also become a catalyst for economic restructuring, as it provides an opportunity to tackle broad challenges and create agreements to share the burden of painful reforms between various groups. Despite the political inertia of recent years, there is now an emerging consensus among Tunisian elites that they should end the war of attrition that special interest groups have long waged against attempts at economic reform. Unless they make the important trade-offs and other decisions needed to achieve this, Tunisia’s political leaders will risk further undermining the legitimacy of state institutions. The resulting rise in economic and social tension could empower anti-democratic forces and destabilise the country. More than ever, the challenges Tunisia currently faces require strong political leadership.

This paper examines why the European Union and its member states should actively push the Tunisian government to take the path of reform. Tunisia’s political reshuffle is far from accidental – it runs deep and is disrupting the country’s party political system. This is particularly noticeable in the rise of radical political platforms, the emergence of new political divisions, and the disconnect between popular aspirations and political representation. Accordingly, Tunisia is at a delicate moment in its transition. These daunting challenges are a stress test for EU-Tunisia relations. In the short term, the EU can encourage international financial institutions to be flexible in their demands of Tunisia, helping restructure the country’s debt to create political space for the government to implement economic reforms. In the long term, Tunisia and the EU should engage in a strategic dialogue that encompasses not only trade and security but also investment, economic modernisation, the green economy, and digitalisation. By doing so, the EU could become the external anchor Tunisia needs to consolidate its democracy.

The anti-establishment vote and a fragmented political landscape

Tunisia’s 2019 elections reflected what political scientist Sharan Grewal calls “a shifting political landscape with a fractured polity and plenty of new faces” – one troubled by demagogy and polarisation. The new Parliament at the Bardo Palace is deeply divided and lacks a clear foundation for a governing coalition. The new president at the Carthage Palace, Kais Saied, is a 61-year-old constitutional law professor who has neither political experience nor a party to implement his agenda.

This fragmented environment – which appears to lack a clear, structured political project – is the product of a years-long decline in the credibility of a political class that has failed to address critical national challenges. Voters’ strong rejection of establishment politicians and parties in 2019 stemmed from the unfulfilled promises the political elite made five years earlier, especially with respect to social and economic reforms. Indeed, the electorate cast a sanction vote – one intended to punish the elite – in both the legislative and presidential elections.

A fractured Parliament

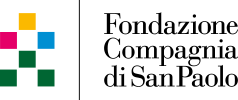

In the legislative election, which involved 31 parties or electoral lists, the previously dominant Ennahda (Islamic Conservatives) and runner-up Qalb Tounes (Heart of Tunisia) – a new secularist party founded by media mogul Nabil Karoui, who owns Nessma TV – won just 24 per cent and 18 per cent of seats respectively. Such fragmentation is understandable given the absence of an electoral threshold. But the new Parliament made a significant break with its predecessor, in which Nidaa Tounes and Ennahda held 40 per cent and 32 per cent of seats respectively, and which included 18 parties or electoral lists.

As Ennahda and Qalb Tounes now control only 54 seats (including two from affiliated MPs) and 27 seats respectively, they fall far short of the 109-seat threshold needed for an absolute majority in Parliament. As such, they are unable to form a government by themselves even though, having campaigned against each other, they are ready to form an alliance.

Attayar (Democratic Current), a liberal anti-corruption party, has allied with the Achaab Movement (People’s Movement) – a socialist, secular, and Arab-nationalist party – to increase its influence in the governing coalition. However, their ideological differences prevent them from converging on all but a narrow set of programmes: the fight against corruption, a break with the practices and elites of the Ben Ali regime, and the defence of economic sovereignty in international agreements.

Four other parliamentary groups hold 65 seats collectively:

- The Karama Coalition (Dignity Coalition), a relatively hardline conservative grouping, came in fourth place, with 19 seats. Its rise as an anti-establishment movement is symptomatic of public frustration with politicians, not least Ennahda’s compromises on religious issues and the values of the revolution. Perhaps the most important characteristic of the Dignity Coalition is its status as the first major electoral competitor to the right of Ennahda: before the 2019 election, Ennahda was the only religiously conservative party represented in Parliament.

- The Free Destourian Party (PDL), with 16 seats, is the heir to Constitutional Democratic Rally, which was dissolved in March 2011. The PDL is an anti-Islamist grouping that opposes the normalisation of Ennahda.

- Reform, with 16 seats, comprises elected representatives of small parties, as well as three from Nidaa Tounes. It is a secular force that is close to the business community.

- Tahya Tounes, with 14 seats, is the parliamentary base of Youssef Chahed, who served as prime minister from July 2016 to January 2020, and who left Nidaa Tounes in the second half of 2018. Chahed is in conflict with Karoui, who holds the former prime minister responsible for his imprisonment from 23 August to 10 October 2019 in connection with an investigation into tax fraud and money laundering. Karoui argues that Chahed engineered the investigation to keep him from campaigning.

In contrast to the parliamentary election, the presidential vote dealt a heavy blow to the establishment by producing a landslide victory for one candidate: Saied. He defeated Karoui with 72.71 per cent of the vote (representing 2.7 million citizens). Saied’s slogan, “the people want” – a deliberate echo of the 2011 revolution – resonated with citizens who wanted to retake power from an opportunistic elite they perceived as having hijacked Tunisian democracy. This anti-party and relatively unknown professor appealed to a majority of Tunisians who were eager to reprimand a political establishment that, in their eyes, had betrayed the 2011 revolution. Saied performed best among young people: 37 per cent of those aged between 18 and 25 voted for him in the first round of the presidential election. Saied is somewhat like the “boomerang of the revolution”. Having built his support base outside the party political system, he seems unwilling to use the presidency to create his own party. This autonomy is probably one of the reasons for his success, but it deprives him of allies within institutions. He derives his power only from his election and his relative popularity among voters.

The end of the “pacted transition”

In the years that followed the 2011 revolution, the Tunisian political scene was organised around the opposition between “modernists” – liberal and leftist actors – and “Islamists” represented by Ennahda. In summer 2013, at the height of tension between the two camps, both Ennahda and representatives of the old regime were pragmatic enough to create a transactional power-sharing agreement. They based the deal on the normalisation of Ennahda in exchange for the reintegration of the former elite, within what has been described as a “pacted transition”. The consensus model that emerged in 2014 brought the leading representatives of each camp together in a unity government and thereby ended a period of acute political polarisation. But it suffered from the limitations of Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes, as well as the political elite’s lack of public credibility. Nevertheless, the 2019 elections may have finally ended the pacted transition.

The consensus model has a meagre track record on social and economic reforms. It suffered above all from the state of permanent crisis in Nidaa Tounes. Unable to restructure itself, the party was torn apart by clan warfare, particularly that between supporters of former president Beji Caid Essebsi, its founder, and Chahed.

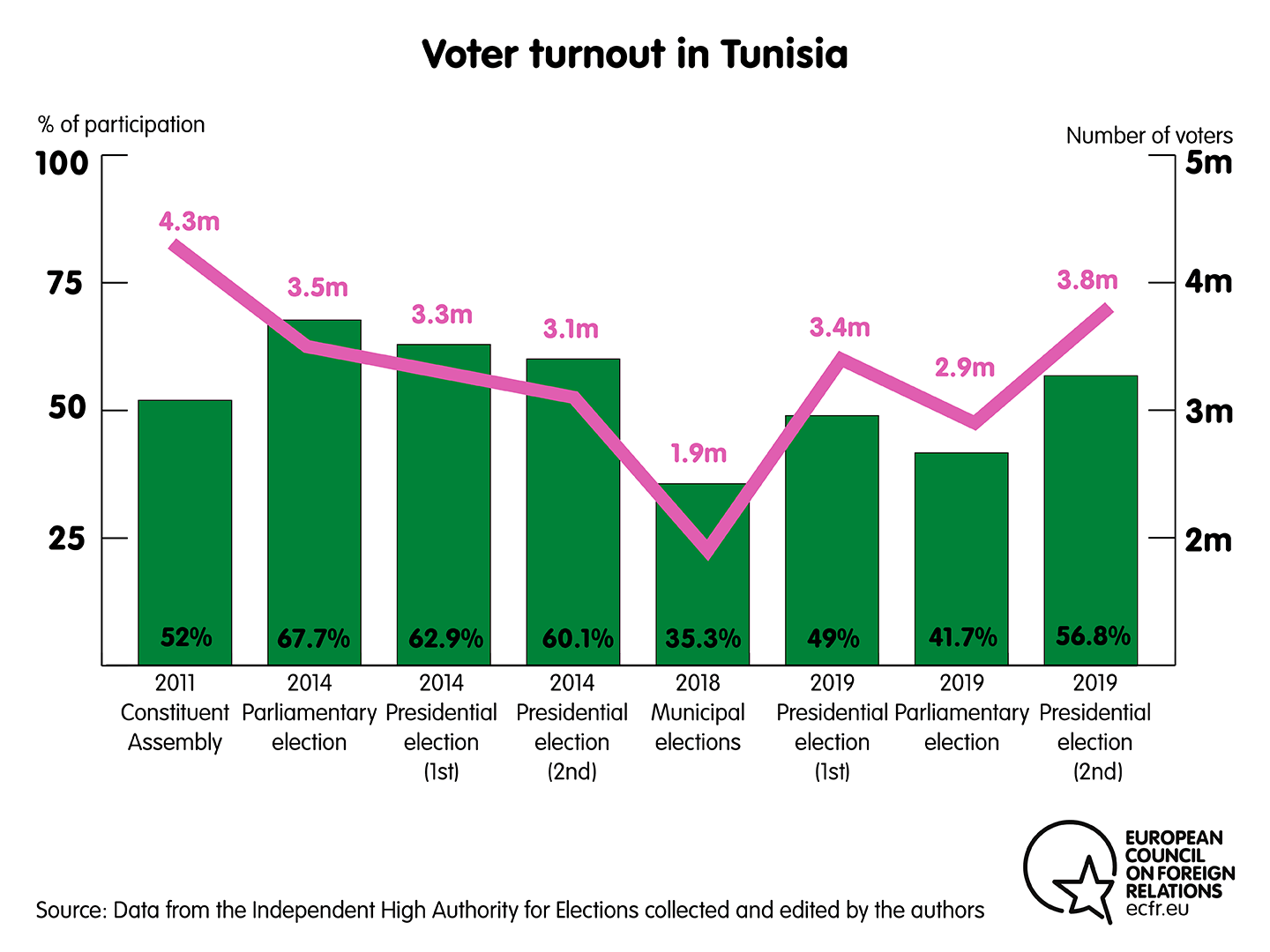

Ennahda, meanwhile, failed to organise the “losers” of the modernisation process – the rural poor and the lower middle-class in peri-urban areas – into a religious base with a programme of economic and social reform. Having been in government from 2011 to 2019 (aside from during the January 2014-February 2015 tenure of Mehdi Jomaa’s technocratic government), Ennahda lost its identity as a protest movement. The party largely devoted its attention to preserving its position of power and managing internal disputes over who would succeed Rached Ghannouchi as its president.

While the consensus model was essential to stabilise the country, it effectively paralysed the parties’ efforts to address economic challenges. They refrained from taking bold decisions and bearing responsibility for the cost of reforms, preferring to engage in a struggle for control of state resources. Their failure to address Tunisia’s deep-set, long-standing economic problems and regional inequality led to persistent economic decline. The country’s financial situation became unsustainable as public expenditure rose from 24 per cent of GDP in 2011 to 30 per cent of GDP in 2018, while tax revenue increased by 23-25 per cent in the period. The resulting financial imbalances caused an increase in external debt from 44.5 per cent of GDP in 2011 to 85.5 per cent of GDP in 2019. Public spending also rose, but this mostly benefited insiders – through mechanisms such as salary and benefits increases for civil servants – rather than the unemployed or the long-neglected residents of the country’s interior. Almost every year since the revolution, large civic protests have taken place in the interior, while irregular emigration has increased.

The architects of the consensus model not only reneged on their promises to create a more effective government but also clung to power through opaque negotiations between elites, as well as compromises that maintained the status quo. They kept protest movements out of the public policymaking process, dealing with them only in short-term clientelist arrangements. The consensus model may have stabilised Tunisian politics after 2013, but it left social challenges wholly unaddressed – thereby exacerbating popular discontent. It strengthened the government’s parliamentary base but widened the gap between the parties and their constituencies. Tunisians’ growing disillusionment with the political process shaped the outcome of the 2019 parliamentary election, in which they punished all parties involved in the pacted transition.

Nidaa Tounes – which took 86 seats in Parliament in 2014, before splits within the party reduced this to 25 seats – won just three seats in the 2019 election. The parties that spun off from Nidaa Tounes, Tahya Tounes and Machrou Tounes, saw the number of seats they controlled fall from 43 to 14, and from 15 to four, respectively. Their junior coalition partners fared even worse, with the Free Patriotic Union losing all 16 of its seats, and Afek Tounes losing six of its eight seats. Frustration with the compromises made by Nidaa Tounes also contributed to the rise of the neoliberal Qalb Tounes and Abir Moussi’s authoritarian PDL – both of which championed Nidaa Tounes’s original demand for the revival of a strong “Bourguibist” state (named for the secular policies of former president Habib Bourguiba).

Disenchantment with established parties, not democracy itself

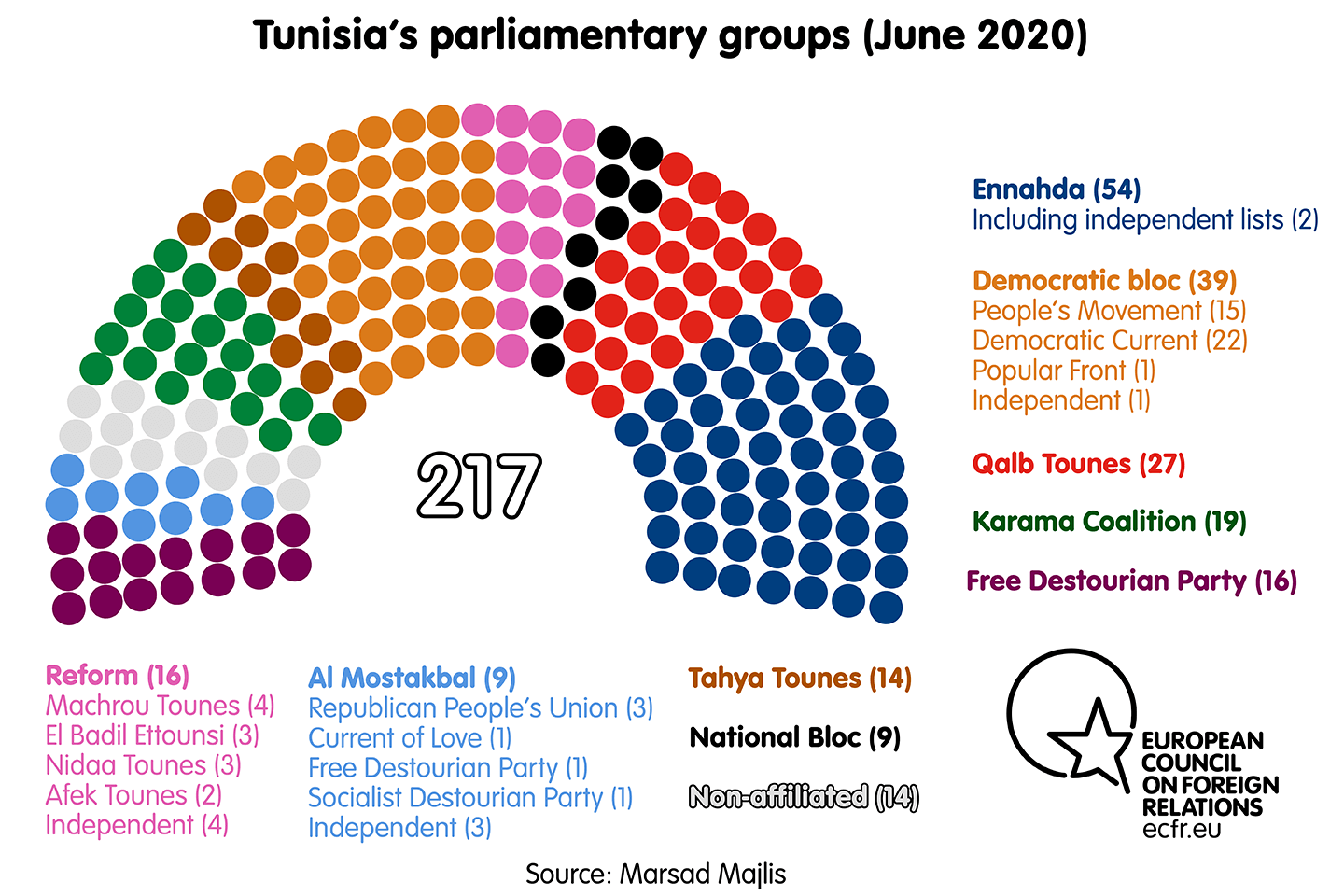

The disruption of the political landscape is not the only effect of citizens’ discontent with the pacted transition. Voter turnout in some elections has fallen significantly in recent years, from 67.7 per cent in the legislative elections of 2014 to just 35 per cent in the municipal elections of 2018.

The stark contrast between self-absorbed manoeuvring within the elite and broad socio-economic decline has created concern among some observers that Tunisians might become increasingly supportive of an authoritarian solution. For example, a survey published by Afrobarometer in September 2018 argued that, “in tandem with a perceived lack of improvement in the government’s ability to handle the main challenges facing the country, we see a drastic decline in Tunisians’ support for democracy”. Only 46 per cent of respondents to the survey said they preferred democracy to any other form of government, a decline of 15 percentage points since 2013. However, the fact that the PDL, which is openly hostile to the revolution, won just 6 per cent of the vote in the 2019 parliamentary election suggests that, so far, there is a lack of support for authoritarianism among Tunisians.

The 2019 elections reflect disenchantment with established parties rather than with democracy itself. Tunisians do not contest democratic principles so much as the form they have taken since 2014, characterised by a cartel of political parties that monopolised power under the guise of a consensus. As such, the outcome of the 2019 elections provides an opportunity to correct the trajectory of the democratic process. And several dynamics give cause for hope in this. Voter turnout for the presidential run-off between Karoui and Saied was the highest it has been since 2011, at 3.8 million. Those who supported Saied in the first round included 32.9 per cent of citizens who did not vote in 2014 and 13.3 per cent of new registrants. These results reflect people’s desire for a profound political renewal, efficient government, and better public policy.

Despite public disappointment with politics since 2011, the turnout in the 2019 parliamentary and presidential elections shows a commitment to democracy. Tunisians still have faith in their capacity to influence politics. However, the democratic system will need to repay this faith. The consolidation of democracy in Tunisia will require greater representation for the large swathes of the population who have traditionally been marginalised, as well as a new approach to addressing the country’s social, economic, and cultural challenges.

A disrupted party political system

In the aftermath of the 2019 elections, it is misleading to view the political system as being divided between Islamists and secularists. The Dignity Coalition, for instance, goes beyond a solely Islamist political agenda. Its members emphasise the need for a break with the Ben Ali regime’s socio-economic and cultural system, positioning themselves at the crossroads of sovereigntist ideals and cultural conservatism. And people’s aspirations on issues such as governmental effectiveness, national sovereignty, and morality in public life draw the attention of a broad spectrum of political forces, ranging from ultra-secularists to ultra-conservatives. However, their diversity makes it impossible for them to build a common policy platform. The interplay between old and new divisions has created a political landscape characterised by deep uncertainty.

Political parties disconnected from society

The parties that formed under the Ben Ali regime – legally or in secret – suffered from the legacy of an authoritarian system that had prevented them from gaining popular support. With the exception of Ennahda, they disappeared from the political scene after the revolution.

Post-2011 democratic practices have done little to close this gap between parties and the people. Public protests focused on specific issues (such as access to employment, water, and income from natural resources) and community initiatives have not gained organised political representation. Even the Marxist-inspired left has failed to branch out beyond intellectual circles and union bureaucracy.

Most of the parties that emerged after the revolution were created by high-profile individuals who saw them as little more than vehicles for their personal ambitions. All these factors have prevented the parties from establishing themselves among the public.

Ennahda has outlasted its erstwhile allies due to its well-organised and long-established grassroots and the loyalty of its supporters, whom it provides with a political identity forged in the traumatic experience of repression. The failure of Ennahda’s candidate in the presidential election and its losses in the parliamentary vote stem from its inability to broaden its electoral base with a renewed policy programme. This decline has created divisions within Ennahda and weakened its overall position.

Qalb Tounes may have not yet held a party conference, but it has already captured some of Nidaa Tounes’ political territory by forging a modernist identity of its own. Its success is mainly due to a charity operation Karoui launched in 2017 to burnish his image on Nessma TV. Particularly active in north-western governorates (which are among the most disadvantaged in the country), the media operation has enabled him to take up the mantle of popular demands for a state capable of effective social and economic reforms. However, this exercise in clientelism provides no new response to social challenges. Those who have rallied to Karoui’s group out of opportunism have weakened its parliamentary base – which has already lost one-quarter of its MPs since the election last year.

With Ennahda and Qalb Tounes divided and in decline, issues that are seen by the public as key to social reform, such as national sovereignty and morality in public life, have slipped off the government’s agenda. And political forces that focus on these topics are too disparate to form a functional alternative government.

Strong popular aspirations without political representation

The issue of national sovereignty, championed by Saied, has gained momentum in the public debate in recent months. In the 2019 elections, it was one of the top issues promoted by emerging political forces, albeit in an uncoordinated and sometimes demagogic manner. The Karama Coalition has taken over Ennahda’s identity as a protest movement. The PDL sees the revolution as an international conspiracy and wants to erase its achievements. The People’s Movement shares pan-Arabist parties’ hostility to Western influence.

The deterioration of Tunisia’s fiscal situation and balance of payments has led to a debt spiral. The country was twice forced to request support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which the organisation granted in return for a pledge to reform public finances and engage in structural economic reforms.

The combination of financial dependency and foreign powers’ interference in domestic debates on issues such as the criminalisation of homosexuality and inheritance equality has generated public hostility. This likely contributed to the prominence of sovereignty in last year’s election campaigns. But debates on sovereignty also reveal the lack of a national strategy to deal with the demands of the population, thereby weakening the Tunisian government’s position in international negotiations.

The other strong popular demand that emerged during the election campaigns related to morality in public life, focusing on corrupt figures who block structural change to maintain control of a rentier economy. The prominence of the issue was key to Democratic Current’s success in the parliamentary election and contributed to Saied’s victory in the presidential race.

Saied’s rise from the peripheries of the political class and his lack of connections with vested interests have helped him become a focal point for the electorate’s aspirations. In this, he capitalises on his image of personal austerity; his proximity to the people; his commitment to the fight against corruption and the ideals of the revolution; and his stance on sovereignty. Saied has come to symbolise the idea of equality under the law due to his profession, of a non-partisan and neutral state in his rejection of party politics that hijacks the state, and of cultural belonging through his use of literary Arabic (sometimes at the expense of a clear message). But his absence from party political contests – and, accordingly, his lack of an affiliated political group in Parliament – limits his influence on public affairs.

Nevertheless, Saied remains attuned to the priorities of working-class and young voters. If these popular concerns do not translate into public policy, there is a risk that Tunisia’s politics will drift towards demagogy and elite rivalry, and away from democracy – to the detriment of the state and the people.

An era of stable uncertainty

As discussed above, the party political landscape created by the 2019 elections prevents Ennahda from forming a coalition government. The fragility of Fakhfakh’s governing coalition has increased tension between the executive and legislative branches. Although Tunisia’s constitution is designed to absorb such tension through a balance of power, the disconnect between public concerns and party representation threatens to undermine the entire system.

Minority government

In the aftermath of the 2019 elections, Ennahda assembled a one-off alliance – along with Qalb Tounes and the Karama Coalition – to elect Ghannouchi as speaker of the assembly, a key position for monitoring the link between governmental and parliamentary work. However, Ennahda was unsuccessful in its attempt to win support for its nominee as prime minister (a move it was entitled to make as the largest party in Parliament). Jemli, who served as secretary of state for agriculture after the revolution, was unable to overcome the mistrust between Ennahda and its main allies, Democratic Current and the People’s Movement, to form a coalition government. And when he was even unable to convince them that he was independent enough to obtain the investiture of a team of “experts” – selected on the basis of their competence, integrity, and independence – he understood that there was no way to build a governing coalition led by him.

On 10 January, a parliamentary vote of no confidence in Jemli exposed Ennahda’s lack of natural allies, its excessive focus on internal tensions, and its tendency to make compromises with opponents to stay in power (which increased these tensions and eroded its electoral base). The vote opened the floor for Saied to intervene to identify the candidate “judged most able to form a government” under the constitution. This paved the way for Fakhfakh to become prime minister, despite the fact that he was a member of a party that had no seats in Parliament and that received just 0.34 per cent of the vote in the 2019 presidential election (Democratic Forum for Work and Freedom, which was a member of the ruling troika between 2011 and 2014).

Saied and Fakhfakh share a concern about, among other things, social challenges and the need to end the dominance of established parties. After weeks of intense negotiations, Fakhfakh secured parliamentary support for a government formed of ten parties and independents. This patchwork of party representatives and independent technocrats excludes Qalb Tounes and the Karama Coalition. The coalition government is structured around an alliance between Fakhfakh and the Democratic Bloc formed mainly by Democratic Current and the People’s Movement, which are united around a broadly reformist and anti-corruption agenda. Relatively side-lined in strategic governmental decision-making, Ennahda seems limited to an uncomfortable position in which it guarantees support for the government in Parliament. Ennahda appears to be trapped between a governing coalition in which it does not play a pivotal role and a parliamentary alliance (with Qalb Tounes and the Karama Coalition) that was crucial to the election of Ghannouchi as parliamentary speaker.

The governing coalition is highly unstable due to the entrenched rivalries and ideological differences between its members. As soon as he was appointed, Fakhfakh found himself at the head of a government whose make-up Ennahda wanted to change – as he had explicitly broken with the consensus model by excluding Qalb Tounes and the Karama Coalition. Fakhfakh excluded Qalb Tounes from the government because of Karoui’s legal problems, and because Saied’s role as a champion of morality in public life led him to oppose this party.

As a result, Ennahda makes no secret of its desire to include Qalb Tounes and the Karama Coalition in the governing coalition. But the three parties’ loss of influence in Parliament – especially after a wave of resignations by Qalb Tounes MPs – prevents them from forming an alternative government.

The health, economic, and social crisis created by covid-19 – which hit Tunisia in early March – has temporarily eased some of the party political pressure on Fakhfakh’s government. But the tension between rival parliamentary groups is set to last for a long time.

Exhausting competition between centres of power

Tunisia’s constitution is designed to prevent the reconstitution of personalised rule and the dominance of a single party over the state. To counter these two risks, members of the Constituent Assembly tempered Parliament’s influence by instituting a president with autonomous powers in defence and foreign affairs, and by electing him through universal suffrage to reinforce his legitimacy. The government is positioned at the point of equilibrium between the parliamentary and presidential centres of power.

The 2019 elections established two competing sources of legitimacy. The first is located in Parliament and managed by ailing political parties; the other in the office of the president – who, as previously discussed, has strong popular support but lacks a parliamentary counterpart.

The presidency and Parliament are competing for influence over the governing coalition. At stake in this contest is control over the parliamentary – and, therefore, the reform – agenda. Strategically, Ennahda fears a loss of influence within the governing coalition that would threaten its efforts at integration, and would weaken its capacity to control state resources, as well as bureaucratic appointments. This will inevitably affect its patronage networks and its prospects of electoral success.

At first, the outbreak of the pandemic seemed to intensify the rivalry between the new prime minister and Ennahda. The party suspected that Fakhfakh would try to seize control in a manner that raised his profile and established him as a new centre of power. But, after weeks of negotiation, Parliament voted to allow him to rule by decree during the crisis, under certain constraints.

The government has gained power through its successful management of covid-19. The health crisis revealed its capacity for decision-making and implementation, overseen by a prime minister who provided strong leadership and thereby boosted the legitimacy of his office. As the government’s success in managing the health crisis showed, governmental efficiency is indispensable to strengthening the legitimacy of the political system.

With the end of the lockdown, political divisions are re-emerging and intensifying. This return to normal politics seems to go hand in hand with a renewed refocusing on party rivalries, to the detriment of efforts to address the public’s concerns. The escalation of geopolitical rivalries in Libya contributes to this process. On 3 June, the PDL put forward a parliamentary motion that denounced the Turkish intervention in Libya. The motion – which received the support of 94 MPs, including members of the governing coalition – increased polarisation and further weakened the governing coalition. It was widely regarded as a challenge to Ennahda and Ghannouchi, who responded by calling for the redefinition of the coalition to make it coherent and create a sense of solidarity among its members. He advocated the inclusion of Qalb Tounes and the Karama Coalition in the ruling coalition, openly criticising Tahya Tounes and MPs who voted for the motion.

These political divisions have been exacerbated by rivalries and an absence of coordination between the president, the prime minister, and the parliamentary speaker. Such coordination is particularly necessary in the current environment, for at least two reasons. The first concerns the need to strengthen the governing coalition to support its bills in Parliament. This would give Fakhfakh the latitude to conduct reforms. The second reason concerns the need to avoid conflicting agendas in the coming months, especially since Saied announced that he would present bills to Parliament to meet popular demands related to public services, social security, and the implementation of the recommendations of the transitional justice commission. Ghannouchi, who has been weakened by rival MPs’ efforts to organise a no-confidence vote in him, would like to improve his relationship with the president and the head of the governing coalition to secure his position. Coordination between the three leaders would largely end competition between power centres, a necessary step in implementing an economic recovery programme.

How the covid-19 crisis provides an opportunity for reform

In early March, a few days after winning a parliamentary vote of confidence, the government led by Fakhfakh learned of the first confirmed case of coronavirus in Tunisia. Fearing the collapse of the public health system, the administration took a proactive approach towards preventing the spread of the virus. By mid-March, the government had suspended all international flights and sealed Tunisia’s borders. It closed schools, restaurants, and mosques, while cancelling public gatherings for cultural and sporting events. And it introduced a night-time curfew. These strict measures, which largely shut down the country, proved to be effective in controlling the spread of the pandemic. By 17 June, Tunisia had recorded only 1,128 confirmed cases of covid-19, and 50 deaths from the disease.

The impact of the pandemic on Tunisia’s economic challenges

While the government’s restrictive measures have proven to be effective, the pandemic is deepening inequality in Tunisia. This is particularly evident in access to health services. At the beginning of the crisis, the country had 331 intensive care beds, equivalent to only three beds per 100,000 citizens. There are no such beds in the country’s long-neglected interior and border regions.

Furthermore, the pandemic increased economic pressure on a country that already faced hardships such as imbalances in its public finances. Covid-19 has had a severe impact on the economy, primarily hitting the most vulnerable social groups. Informal economic activity, which accounts for nearly 40 per cent of GDP and employs around 32 per cent of the workforce, dropped by 60 per cent following the onset of the crisis. One-third of households declared they had to reduce the quality and quantity of their food consumption during the lockdown.

The damage to the formal economy is especially clear in the tourism sector, which has experienced a decline of 23 per cent since 2019. Tourism accounted for 5 per cent of GDP and 4.5 per cent of the employed labour force in 2019. Experts project that the sector will not return to normal before 2022, at the earliest. The manufacturing sector, which accounts for approximately 18.5 per cent of the employed labour force and 15 per cent of GDP, is also under intense strain given the disruption of global supply chains and the lockdown in Europe. Tunisia’s exports have dropped by 8 per cent this year, primarily due to a sharp fall in European demand, as well as the closure of manufacturing plants, in response to the covid-19 outbreak. The disruption of operations in manufacturing will most likely cause layoffs of workers hired on a temporary basis. And the virus has also had a heavy impact on the airline industry, exacerbating the problems faced by flag carrier Tunisair.

These disastrous developments have prompted the government to prioritise support for the economy. The Fakhfakh administration quickly announced an assistance package worth 2.5 billion dinars ($876m) to help safeguard businesses and preserve jobs. The government also allocated 150m dinars ($53m) to direct social assistance, providing 700,000 people whose activities were affected by the lockdown with a cash transfer of 200 dinars ($70).

Organisations such as the IMF, the World Bank, and the EU have collectively granted around $1.4 billion in aid to Tunisia. The IMF provided $745m, while the European Commission allocated €600m to a macro-financial assistance package. However, this is not sufficient to offset the effects of the pandemic in Tunisia.

The crisis is likely to exacerbate structural economic problems the country has struggled with for more than a decade, including a decline in GDP growth rates, high unemployment, low levels of investment, and an increase in public debt. According to the IMF, growth will decrease from 2.7 per cent in 2019 to -4.3 per cent in 2020. The average GDP growth rate stagnated at 1.8 per cent between 2011 and 2019 – in comparison to around 4.6 per cent between 2005 and 2010. The unemployment rate is likely to reach 21.6 per cent in 2020, with an additional 274,500 people out of work – an increase from approximately 15.5 per cent in 2016 and 13 per cent in 2010. According to the United Nations Development Programme, the poverty rate will increase from 15 per cent in 2019 to 19.2 per cent in 2020. Tunisia will also suffer from the recession in European countries such as France and Italy, to which it is closely tied through investment, remittances, and exports. Economists estimate that foreign direct investment in Tunisia will drop by 30-40 per cent. This, combined with a decline in remittances and a rise in state expenditure, will widen macroeconomic imbalances and increase public debt. Public debt is projected to reach 90 per cent of GDP in 2020 – up from 40 per cent in 2010 and 73 per cent in 2019.

Public policy reforms at a turbulent time

The precarious economic situation restricts the Tunisian government’s room for manoeuvre as it attempts to implement a tough reform agenda. This agenda covers everything from the public sector, particularly state-owned enterprises, to a rentier system that damages the business environment and reduces investment, to social justice issues such as the integration of marginalised groups (not least the unemployed, and people working in the informal economy and in the interior).

In the near future, debt restructuring would provide much-needed political space for the government, which is currently preparing a recovery plan for 2021-2025. This plan should create an opportunity to implement structural reforms. Rather than focusing on quick fixes, the recovery should address the systemic challenges the country has faced for almost a decade. This is particularly the case for the fiscal situation, which has long called for tax reform to address the deficit. The reform of the taxation system seems to be unavoidable, as Fakhfakh said in June 2020 that external debt had reached “dangerous levels” and was becoming unsustainable. Tunisia needs 4.5 billion dinars ($1.6 billion) to fund its recovery programme and overcome its financial woes. In this context, the reform of state-owned enterprises, whose losses increase the burden of national debt, has also become a high priority.

Between 2011 and 2019, Tunisian governments presented themselves as employers of last resort, significantly increasing the size of the public sector. More than 90,000 people, the majority of them former contract workers, joined the public sector in 2011 and 2012. This doubling of annual recruitment numbers increased the number of staff employed by the sector (excluding publicly owned companies) to 616,000. Along with promotions and salary increases, the recruitment drive led to a rise in the public sector wage bill from 11.8 per cent of GDP in 2011 to 14 per cent of GDP in 2019.

The poor governance of state-owned enterprises presents another major challenge. Following the onset of the covid-19 crisis, the government announced a bailout designed to restructure these companies, including Tunisair. The process will not be easy, given that massive recruitment in the public sector has been a critical tool of wealth distribution and state control since independence – albeit somewhat less so since the structural adjustments of the mid-1980s. Despite its massive role in the economy, public sector employment has proven to be fiscally unsustainable and ineffective in preventing the emergence of socio-economic grievances. Although this became abundantly clear during the 2011 revolution, governments in power since then have perpetuated the old system, increasing public employment to maintain patronage networks and a modicum of social harmony.

By dismantling the rentier system, the government would unleash Tunisia’s investment potential. Since 2011, political competition has pushed political parties to rely on firms for funding by providing them with economic privileges in return. These arrangements secured the profits of politically connected businesses under the guise of pluralism. The deterioration of the business environment and the prevalence of cronyism has pushed private companies to shift their activities to relatively unproductive sectors. Far from dismantling the patronage system, pluralism consolidated the position of new interest groups linked to political and business elites.

Under its plan to assist the unemployed and citizens who work in the informal sector, the government plans to provide hundreds of thousands of Tunisians with access to property rights by granting legal status to houses that were built decades ago. This will help these people open bank accounts and access the wider financial sector. The government also plans to distribute state-owned land to unemployed young people and encourage them to organise within a framework of social and economic solidarity. To this end, on 18 June, Parliament voted on a law on social and economic solidarity. This law aims to generate more than 200,000 jobs and increase GDP by 10 per cent in the coming years.

Despite the divides within the governing coalition, the economic crisis triggered by the pandemic might prove to be an opportunity for Tunisia to implement these bold and necessary reforms. However, this will be challenging given the fragility of the political environment and the fragmentation of Parliament. It will require the government to build a coalition for change based on an agreement on burden-sharing between social groups. This approach will be especially crucial given that the government will probably be forced to implement unpopular austerity measures. On 14 June, the prime minister announced that the public sector would be subject to a freeze on salaries – and, potentially, wage cuts if the situation did not improve.

The crisis could make some constituencies more open to change, but only if political leaders put forward a clear vision and a narrative on overcoming the challenges Tunisia faces. The government will have to secure the support of the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade, and Handicrafts (UTICA) and the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT), which have drastically limited post-2014 governments’ capacity to carry out economic reforms. Between 2014 and 2019, politicians were often eager to secure the organisations’ support to remain in office and, as such, avoided antagonising them. Having mediated discussions on the consensus model that emerged in 2014, the UGTT and the UTICA gained veto power over some of the government’s decisions. This was particularly apparent in relation to the privatisation of state-owned enterprises, which the UGTT rejected. The organisation claims to oppose such a move out of a concern for protecting jobs. However, this opposition has often come at the expense of the financial viability of state-owned enterprises.

So far, economic elites have refused to accept higher taxes for big businesses and property owners. Accordingly, fiscal restructuring has generally been based on increases in indirect taxation and a reduction in government expenditure. This has placed the burden of reform on the lower and middle classes in a way that has undermined popular support for tax reform. Given that consumption taxes provide around 57 per cent of total tax revenue (and direct taxes the remainder), the government now needs to raise much-needed revenue while distributing the burden of this shift across socio-economic classes. Yet – given previous governments’ hesitance to raise taxes on the wealthy, and given the fragility of the governing coalition – it remains to be seen whether the current leadership will implement this measure.

In the wake of the 2019 elections, economic reforms will be highly dependent on negotiations and compromise within Tunisia’s governance system. A consensus that can support painful reforms is key to the process. However, in contrast to the situation in 2014-2019, the government will not have the financial latitude to placate the state-dependent middle classes – the main constituency of the UGTT – through either higher wages, greater public employment, or subsidies. Nor can it pay off the economic elites represented by the UTICA.

Tunisia should take advantage of its institutionalised forms of representation for workers and employers by negotiating over the distribution of the burden of economic reforms, seeking a socio-economic consensus and opening up much-needed political space for the government. Divides within the governing coalition might hamper these attempts. But the government has no choice but to invest political capital in the effort. The main challenge will be in including the UGTT and the UTICA in a broad settlement while managing competing interests.

In a political environment defined by the collapse of the consensus model and a rise in public distrust of established parties, the government should initiate a strategic debate on Tunisia’s development model. The covid-19 crisis will create opportunities for this by reshaping trade and accelerating the global trend towards shorter supply chains. European companies may review their just-in-time manufacturing processes and use of suppliers in Asia, giving priority to manufacturers closer to home. And Tunisia could become an attractive investment environment for these firms. However, to seize the opportunity, the country needs to rethink its role in the global trading system, revamp its infrastructure and logistics networks, and offer investors more than just a convenient geographical location.

Pressure on the Tunisian economy and global economic uncertainty will undoubtedly initiate some form of change in this area. The weakness of the governing coalition and the need to survive politically might push it to maintain business as usual rather than challenge vested interests. Yet the development model Tunisia built in the 1970s – which is based on tourism and low-cost outsourcing, with incentives for investment and access to international markets centred on low wages and restrictions on the labour movement – is no longer sustainable. The country’s politicians, along with organisations that represent its employers and employees, need to find a compromise that shares the burden of structural economic transformation and ends the war of attrition special interest groups have waged since 2011. If it fails to achieve this, the government may inadvertently destabilise Tunisia and empower its anti-democratic forces.

Conclusion

Only effective and stable government can rescue Tunisia from the health and economic challenges it faces. More than ever, the country needs a government able to manage crises, design and implement policies, and provide social and economic solutions to long-lasting problems. This is key to strengthening the legitimacy of Tunisia’s democratic institutions. Paradoxically, the effects of the covid-19 crisis could create momentum to side-line vested interests, short-sighted corporatism, and onerous bureaucratic procedure. In one sense, the crisis might have benefits. But this will mainly depend on the capacity of the political class to make good use of the situation.

As divisions within the coalition government show, there is a need to balance political unity with parties’ distinct identities. There are important differences between Ennahda, Democratic Current, the People’s Movement, and Tahya Tounes. Yet they must reach an agreement on crucial issues – primarily, the priorities of the covid-19 recovery plan. Building on the unity they have shown in their response to the pandemic, they must launch a programme of social and economic reforms, and manage the veto power of special interest groups. Given that it is impossible for them to agree on a common policy agenda, they should strike a deal in which each party sets its own priorities for the recovery plan.

The arrangement would be no substitute for a coherent reform agenda, but it would help in identifying and communicating each party’s demands for specific legislation and projects. Parties could facilitate the process by forming a strategic planning group, which would act as the engine of the coalition. This would make it easier to strike deals within the coalition and develop a collective approach to crucial issues, projects, and parliamentary bills. There is also a need for coordination between the agendas of the president, the head of the government, and the parliamentary speaker. The three leaders could organise monthly meetings and establish a committee to coordinate, and implement follow-up actions on, their agendas. This would create much-needed coherence between the executive and legislative branches, building a sense of unity in Tunisia’s interactions with its international partners, particularly those in Europe.

Tunisia cannot find a solution to its social and economic problems without the support of its international partners, especially the EU. The country’s sources of external financing have begun to dry up as the international community grows weary of the sluggishness of its reforms. But international financial institutions, creditors, and investors need to be flexible if the Tunisian government is to carve out the political space to implement substantive economic reforms.

The EU should help Tunisia reach agreements with other international partners on debt restructuring, providing the government with some room for manoeuvre. The bloc can play an important role by encouraging the development of expertise on economic governance, building up the capacity of the Conseil d’Analyse Economique – which is the chief advisory body to the prime minister on economic policy – and the Institut Tunisien d’Etudes Quantitatives, as well as think-tanks and research centres. Given that an effective response to the economic and social problems created by covid-19 will require innovative thinking, these institutions could play a major role in advising the government, exploring policy options, and generating public debate on economic governance.

Beyond finance, Tunisia needs to engage in a strategic dialogue with the EU. With the arrival of a new leadership in Brussels and the 2019 elections in Tunisia, the sides can open a new chapter in their relationship. Many in Tunis perceive the European Neighbourhood Policy framework as excessively bureaucratic and driven mainly by technocrats. There is an urgent need to renew the partnership’s priorities and politicise this framework. A strategic dialogue between Tunisia and the EU would allow for a major rethink of their priorities for 2021-2027. The country needs a political partnership with the bloc – and this would be in line with the European Commission’s new emphasis on geopolitics.

The strategic dialogue should cover the modernisation of the Tunisian economy; commercial innovation; the green economy; the reconfiguration of supply chains; digitalisation; trade; investment; and, of course, security and migration issues. Such a dialogue would provide incentives for Tunisian political and economic elites to implement reforms, as they could benefit from integration with the European market. Most importantly, the process would allow the EU and Tunisia to identify their common interests – beyond the financial assistance and trade relations that, so far, have been the exclusive focus of their talks on a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement. A strategic partnership would be a source of stability for Tunisia in an increasingly uncertain economic and security environment.

Business as usual is not an option for EU-Tunisia relations. The sides need to build a creative framework for their relationship and to come up with new instruments to deal with the changing political situation in Tunisia. This would help them address the increasingly sovereigntist public mood in the country; geopolitical turmoil in the Maghreb; rising security concerns mainly related to the conflict in Libya; and socio-economic challenges created by the coronavirus. All these trends heighten the need for the EU and Tunisia to rejuvenate their partnership in ways that protect their common interests.

About the authors

Thierry Brésillon is an analyst who has been based in Tunis since 2011. He is correspondent for various newspapers (including Belgium’s Le Soir) and has written for Le Monde Diplomatique, Orient XXI, and Middle East Eye. He was previously editor-in-chief of Faim et Développement Magazine, published by the NGO CCFD-Terre Solidaire.

Hamza Meddeb is an assistant professor at the South Mediterranean University in Tunis. He is also non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center. His research focuses on the political economy of the democratic transition in Tunisia, as well as the political economy of conflicts in North Africa. He is the author of “Tunisia’s Geography of Anger: Regional Inequalities and the Rise of Populism” (Carnegie, 2020) and “Ennahda’s Uneasy Exit from Political Islam” (Carnegie, 2019), and co-author of L’Etat d’injustice au Maghreb. Maroc et Tunisie, Karthala (2015), with Irene Bono, Béatrice Hibou, and Mohamed Tozy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Julien Barnes-Dacey and Anthony Dworkin from ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa Programme, as well as several interlocutors and officials in Tunisia, for their thoughtful analysis and engagement with the ideas laid out in the paper. Thanks also go to Danielle Tan, Mourad Smaoui, and Nejmeddine Hamrouni for their input. Jean Bossuyt and Zakaria Ammar from the European Centre for Development Policy Management deserve special thanks for their advice on economic governance issues in Tunisia – though the opinions expressed in the paper are solely those of the authors. ECFR’s editorial team also deserves special thanks for its support.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.