Pushing the boundaries: How to create more effective migration cooperation across the Mediterranean

Summary

- In 2018 Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia roundly rejected EU plans for ‘regional disembarkation platforms’ out of concern: around the cost of hosting migrants on their own soil; for public opinion; and to remind Europe of their own sovereignty.

- North African governments further point out that they too have migration issues to deal with, including growing pressure on their borders, integration of newcomers, and domestic discontent about migration.

- While the EU’s concerns about irregular migration are legitimate, the proposal for disembarkation platforms was likely a misstep, as it only fuelled tension in the relationship with its southern neighbours.

- That said, Europe and North Africa already have a long and mature relationship when it comes to cooperating on migration matters. The 2018 proposal for disembarkation platforms may now be a non-starter. But opportunities remain for the EU to deepen its partnership working with Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia on border control and – although this area is more contested – on migrant returns.

Introduction

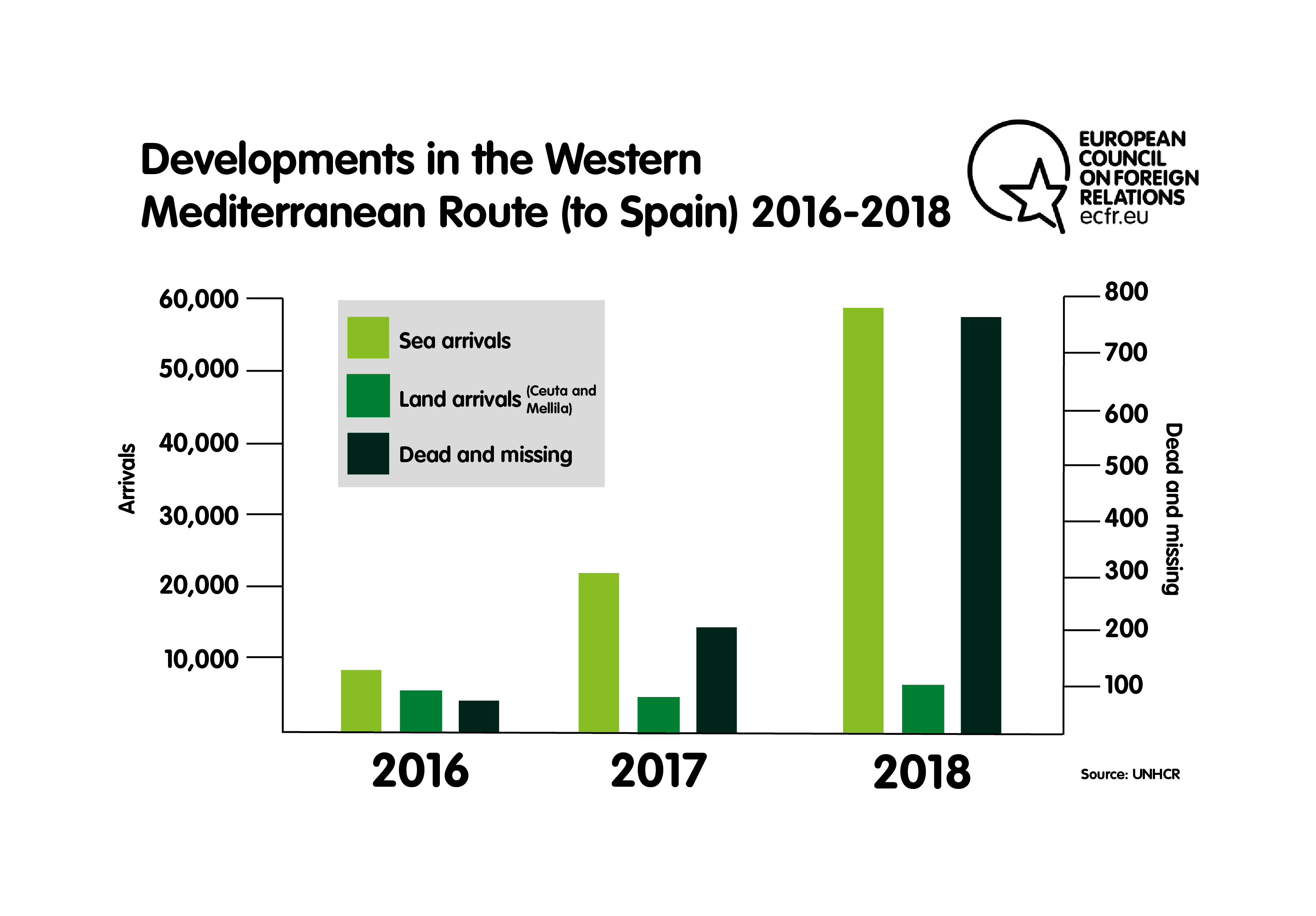

As the European Union strives to stem the flow of migrants across the Mediterranean, its policymakers have repeatedly identified North Africa as key to managing what they consider the ‘migration crisis’. Recent EU and Italian endeavours in Libya have brought down the number of those making sea crossings from Libya. This has diverted migrant flows and resulted in growing pressure on the southern and maritime borders of other Maghreb states. The subsequent rise in popularity of other crossing routes caused arrivals to Spain to leap from 8,162 to 22,103 between 2016 and 2017, and to more than double in 2018. The EU and its member states have therefore now shifted their attention from Libya to other points of departure. They particularly seek to step up joint work with North African countries on: migrant reception; border management; and the return of these countries’ nationals.

Following the EU Council meeting in late June 2018, member state leaders proposed the establishment of “regional disembarkation platforms” in North African countries. This was the last – though by no means the most novel – in a set of proposals seeking to more actively engage Europe’s southern neighbours in migration management. To generate support for the idea, some European leaders pointed to the EU-Turkey deal as a model to emulate. But all North African governments explicitly rejected these proposals. In fact, they point out that they are facing the same migration challenges as the EU, including: problems around acceptance of migrants by the local population; racism; and pressure on public services and finances.

In the light of this resistance, the debate in Europe now appears to have largely moved beyond the disembarkation platforms proposal – though the idea is not completely off the table. At the EU Council summit in Salzburg in September 2018, Austrian chancellor Sebastian Kurz declared that disembarkation platforms “are not essential to solve the problem of illegal migration”; he instead pointed specifically to a need for more cooperation on border management. Since then, it has become clear that the EU and its member states will pay greater attention to finding more practical ways of cooperating with North African countries on returning their nationals residing illegally in the EU, and on tightening border controls. While it is true that both sides of the Mediterranean share an interest in border management – no one wants to host large numbers of irregular migrants – countries in North Africa are not necessarily willing to engage with the whole range of border management mechanisms that the EU offers. And there are challenges to cooperation on migrant return: North African countries usually stress their willingness to accept the return of their citizens who have become irregular migrants in the EU, but some are less likely than others to participate in forced returns. In the context of bolstering relations with North African countries on migration and other issues, president of the European Council Donald Tusk proposed an EU-League of Arab States Summit for early 2019.

This paper seeks to map and contribute to the continuing debate on migration cooperation between the EU and North African states. The first section offers background on the evolving significance of migration in the EU’s relations with North Africa. The second section focuses on Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, examining how these three countries responded to EU requests to establish regional disembarkation platforms and exploring the domestic and international pressure they are experiencing. As these platforms appear to be a non-starter, the subsequent section examines what other tools the EU is likely to reach for instead, principally: enhanced cooperation on border management; and stepping up activity on migrant return. The conclusion considers how the EU and its North African partners can agree to and develop areas of shared strategic interest. Despite the tension over migration and the fraught political and socio-economic context, the EU and countries on both sides of the Mediterranean should be able to maintain and enhance a relationship that, in many ways, is well developed and productive. It is one that could provide all sides with a strong foundation for future cooperation on migration.

Migration cooperation in EU-North Africa relations

Migration has been a constant element in cooperation between the EU and North African countries since the signing of Association Agreements with Tunisia (1998), Morocco (2000), Egypt (2004), and Algeria (2005). These agreements serve as a comprehensive framework for bilateral relations across a range of issues, including migration and mobility. Migration featured strongly in the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), a framework launched by the EU in 2003 to govern its relations with its eastern and southern neighbours. By developing cooperation with the EU within the ENP, partner countries are able to benefit from mobility packages in return for cooperation on readmission and the establishment of a governance system for border management. This includes, for instance, joint patrol missions between EU member states and the partner country.

The impact of the Arab uprisings on migration dynamics in the Mediterranean – through, for example, the inflow of thousands of refugees fleeing Syria towards Europe – has reinforced the relevance of migration in relations between the EU and its southern partners. Since early 2011, the EU has been intent on establishing a structured dialogue on migration, mobility, and security with countries in its southern neighbourhood. This structured dialogue aims to help partner countries strengthen their migration management capacity and to explore the possibility of agreeing Mobility Partnerships with these countries. The Mobility Partnership is a foreign policy tool the EU uses to establish long-term dialogue and operational cooperation with partner countries; it covers various aspects of migration management, including regular migration, border security, and the fight against irregular migration. Alongside this, the Mobility Partnership offers the possibility of negotiating agreements on readmission (to set procedures for returning partner countries’ nationals and third country nationals transiting through their territory) and on visa facilitation. The EU has concluded Mobility Partnerships only with Morocco, in 2013, and Tunisia, in 2014. Meanwhile, talks with Algeria and Egypt have not progressed as these countries have shown little interest in this EU instrument.

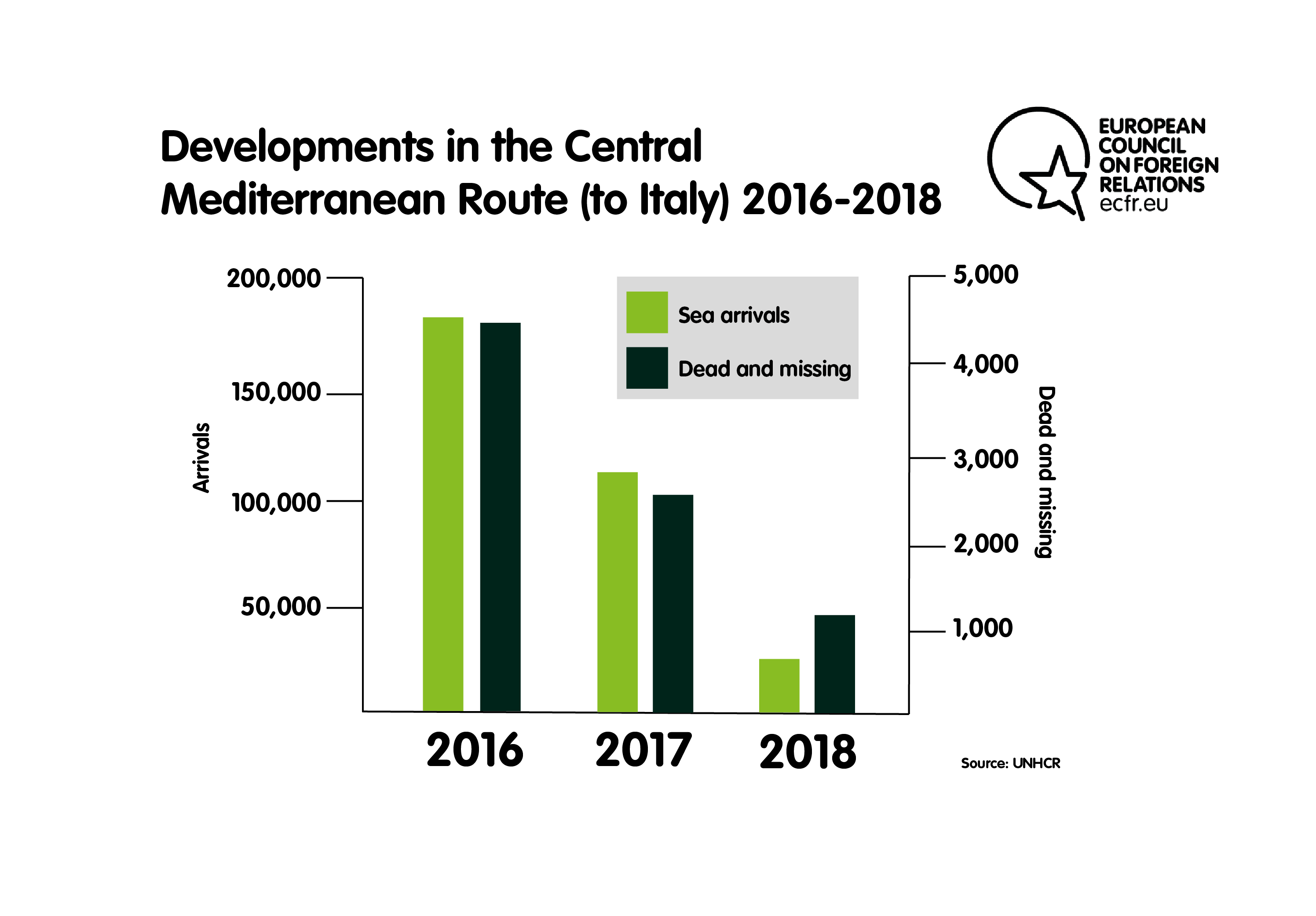

In the recent “crisis”, Libya acted in 2016 and 2017 as the main point of transit towards Europe, accounting for more than 90 percent of arrivals in Italy. Intensified efforts by both the EU and Italy to close the Libyan route towards Europe saw arrivals in Italy drop significantly, from 181,436 in 2016 to 119,369 in 2017, to around 22,000 by November 2018. In Libya, the EU did not act alone on migration. It worked with international organisations, including by supporting the International Organization for Migration (IOM) programme of Voluntary Humanitarian Return to repatriate migrants who are trapped in Libya’s detention centres. The EU also supported the UNHCR’s work on evacuating refugees and asylum seekers to a temporary transit point in Niger, with a view to resettling them elsewhere. Following the release of a major CNN report on slave auctions in Libya in November 2017, efforts to evacuate migrants and asylum seekers from Libya stepped up within a joint African Union, EU, and UN task force that was formed during the AU-EU summit that month. While these joint efforts had some positive results, significant political and practical challenges remain in efficiently tackling the situation in Libya, not least given the complexity of the country. By September 2018, there were fewer arrivals in Italy than at any time since February 2013.

However, the closure of the Libyan route displaced migrant flows; in 2018 Spain became the main point of arrival in Europe, with 58,5669 individual arrivals. Departures have increased from Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. While the majority of those leaving from Tunisia are Tunisians themselves, significant numbers of sub-Saharan migrants transit through Morocco and Algeria. Across Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, disillusionment and dire socio-economic conditions are increasingly driving people, especially the young, to risk their lives at sea. Since late 2017, Tunisians have constituted the largest national grouping of arrivals in Italy: more than 5,000 in 2018, up from fewer than 1,000 in 2016. And, according to Morocco’s migration and border surveillance director, Khalid Zerouali, the authorities “stopped 65,000 attempts at irregular departure from Morocco in 2017 and 25,000 this year”. Moroccans constitute the largest national group among arrivals in Spain, with over 11,400 migrants – while most other arrivals in the country come from west African countries. This increasing pressure on countries’ borders is a challenge for these states and for the EU, which remains the ultimate destination for most of this migration.

The EU has thus shifted its focus to these growing points of departure in North Africa. Its quest for a solution to this challenge comes amid heightened politicisation of migration. The issue now dominates European politics, contributing to the rise of far-right groups and pushing aside pro-EU political parties. Not only that, but migration has threatened to split the EU: reinstating border controls in the Schengen travel area – as many EU countries did during the crisis – defies the notion of a common space. That being said, there is little appetite in member states for receiving new arrivals, and the EU is under pressure to demonstrate that it can ensure adequate control of its borders. It is in this context that the EU is trying to further step up cooperation with North African countries on migration.

The significance of migration in EU-North Africa relations has gradually increased since the 1990s. Migration now poses a challenge shared between both sides of the Mediterranean – although perceptions, interests, and approaches in this realm differ. The EU’s current attempts to reinvigorate collaboration in the area come amid tension that will affect its ability to engage in fruitful and lasting cooperation with its southern partners.

Regional disembarkation platforms: Over before they began?

Building on its cooperation with the UNHCR and the IOM in Libya, the EU attempted to work closely with these international organisations and interested partner countries in North Africa on establishing a new instrument: regional disembarkation platforms. But it has done so without success. Under the proposals, the “platforms” hosted in participating North African countries would hold migrants and asylum seekers who are intercepted at sea before they reach European waters. The EU has explained its idea in the following terms: “disembarkation in a third country is possible if the search and rescue is carried out in the territorial sea of that country by its coast guard or by other third country vessels. If the search and rescue occurs in international waters and involves an EU State’s flag vessel … disembarkation can still take place in a third country, provided that the principle of non-refoulement is respected.” Once they have disembarked, migrants and asylum seekers would be screened, registered, and given adequate assistance based on their individual needs. In return for cooperation on hosting these platforms, the EU would provide “tailor-made and targeted packages” for potential partners and cover all related costs for these platforms. However, while the potential host country, the IOM, and the UNHCR were all poised to be involved in the management of these platforms, there has been little clarity about how they would work in practice.

The EU pursued this idea with the goal of ensuring that migrants do not end up in Europe, and to dissuade irregular migrants from setting out on the journey in the first place. Through the disembarkation platforms proposal, the EU also sought to introduce a mechanism to immediately return migrants to Africa. The EU’s non-paper on regional disembarkation platforms, developed following the EU Council meeting of June 2018, provides some insights into how the EU perceives the functioning of these facilities. Many practical details remain missing, though, and would ultimately depend on consultations once an interested country was identified. The EU had planned to strike deals with partner countries to host these facilities, and to intercept migrants’ boats and tow the vessels to the coast.

Numerous practical difficulties present themselves, even before one begins to grapple with the politics of each North African country. One key challenge is the repatriation of migrants from regional disembarkation platforms to their countries of origin, which is likely to be a lengthy and complicated process. Following their disembarkation in the host country, those who are fleeing harsh economic conditions and who are ineligible for international protection would face return to their countries of origin. These countries would need to identify their nationals among intercepted migrants, as it is common for irregular migrants to lack identity documents. There is no guarantee that countries of origin would cooperate swiftly on returning their nationals. Migrants who remain in regional disembarkation platforms for long periods of time may well then try to seek work in the host country, set out across the sea again, or simply impose a financial cost on the government. For these reasons, the difficulty of successfully returning migrants to their countries of origin remains a significant turn-off for potential host countries.

Of course, not all people in disembarkation platforms would be economic migrants. Many would be fleeing conflicts and therefore would be eligible for asylum under international law. They would need resettlement to other countries: North African states would – due to their weak asylum systems and unfavourable socio-economic conditions – be very unlikely to grant asylum to these refugees. There is a distinct lack of political willingness to do so, in any case. At the same time, resettling refugees in Europe in the current political context would also be very challenging. Even the current experience of transferring asylum seekers from Libya to Niger – just to be provisionally hosted in the UNHCR emergency transit facility – reveals the difficulties of successfully transferring people: the slow nature of the process led Niger to temporarily suspend evacuations from Libya at least once in 2018. If the relocation of asylum seekers within the EU has been problematic, there is little evidence that member states would be willing to take in refugees who were temporarily hosted in disembarkation platforms in non-EU countries. Again, there is a strong likelihood that asylum seekers would remain in these facilities for years at a time.

The EU acknowledges these limitations, stating that resettlement will not be the only viable option for those in need of international protection. However, it is unclear who would take responsibility for those who are not offered resettlement in the EU.

Detaining both migrants and asylum seekers in third countries for an unlimited time may also pose legal challenges if they find themselves in “potentially unsafe conditions”. The EU-Turkey migration deal has exposed some of these challenges. The extended stay of migrants and asylum seekers on the Greek islands presented difficulties, as reception centres there were not adequately equipped to develop from short-stay to detention facilities. This, in turn, raises questions about the time frame of the operation of these platforms – the details of which are also unclear.

Slow resettlement could also potentially shift the objectives of disembarkation platforms from temporarily hosting migrants and asylum seekers to arranging their stay in the country for extended periods and, potentially, the integration of refugees and migrants into the local economy. This is likely why the EU has sought to encourage Tunisia and Morocco to develop their asylum systems – a key element to making them safe countries for returned migrants and asylum seekers.

These practical challenges would apply to any North African country willing to accept regional disembarkation platforms. Therefore, they contribute heavily to how governments respond to EU proposals that incorporate such facilities. Naturally, each country also has its own internal politics and socio-economic factors that weigh in the mix of considerations for their governments.

Morocco

Morocco has always represented a potential EU target for external migrant centres, for several reasons: it enjoys strong institutions; has long cooperated on migration issues with the EU (particularly with Spain); possesses strong security and border control capabilities; already hosts a migrant population; and is undertaking ongoing migration reform. Crucially, Morocco is both an origin and transit country, and has become the main point of departure for Europe, with 65,383 arrivals in 2018 (including 6,814 land arrivals in the Spanish enclaves Ceuta and Melilla). Growing numbers of young Moroccans leave the country by sea to escape socio-economic hardship. Meanwhile, pressure on Morocco as a transit point is unlikely to wane so long as migration drivers in west Africa persist.

The Moroccan government perceives itself as confronting the same migration challenges as Europe – and this is one of the reasons it has refused to host disembarkation platforms. Moroccan officials have repeatedly asserted that their country has no desire to cooperate with the EU on this proposal. Not only is this a matter of national sovereignty, they argue, but Morocco does not want to gain a reputation inside or outside the country as a gendarme of the EU. They consider the regional disembarkation platforms proposal to be a means for Europe to externalise its migration challenges.

Morocco’s handling of the migration question is principally guided by its domestic and foreign interests. Indeed, hosting disembarkation platforms could run counter its domestic challenges, as doing so could create tension: amid high unemployment, anti-migrant sentiment is already simmering in the country. The Moroccan government has been active on this front: for example, it launched a comprehensive migration reform drive in 2013, which incorporated an exceptional regularisation campaign for migrants, to deal with the country’s double status as both a destination and transit country. This is to be complemented by other reforms, such as a new asylum law. The government’s suite of measures has also sought to address internal and external pressure from media and civil society, following past accusations that the government had breached migrants’ rights. These migration reforms aimed to deal with Morocco’s challenges and interests, which essentially concern the need to address the situation of thousands of foreigners it hosts and enhance its external image as a country that takes a humanitarian approach to migration. Morocco’s migration policy essentially aims to serve its national interests rather than merely react to external pressure and incentives.

Indeed, the Moroccan foreign minister, Nasser Bourita, has made clear that placing migrants in detention centres would be inconsistent with his country’s migration policy. For instance, between 2014 and 2017, the government offered legal status to nearly 50,000 migrants, 90 percent of whom came from sub-Saharan Africa. At the same time, the government worked with the IOM and countries of origin on returning those who were not granted a permit to stay. Thus, it does not understand why Europe cannot pursue repatriation directly with source countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The priority for Morocco is to deal with those who are already in the country rather than to reach agreements that could lead others to stay. At the same time, Morocco continues to cooperate with Spain on tightening controls around Ceuta and Melilla, as well as maritime borders. For these reasons, the government feels that it has already met its migration management responsibilities, both for itself and for European partners.

The kingdom’s established approach to migration cannot be separated from its broader external policy and quest for international recognition. Morocco’s leading migration role within the AU makes it even less likely to conclude such a deal with the EU. Most importantly, its activism and growing presence in AU affairs also relates to its strategic interest in gaining international recognition for its claim on the contested Western Sahara. Moreover, Morocco’s activism on migration goes beyond Africa: it co-chairs, with Germany, the Global Forum on Migration and Development. Last year, it hosted the launch of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, the first intergovernmental agreement prepared under the auspices of the United Nations to holistically address different aspects of international migration. The high profile of migration issues is likely to militate against the government agreeing any deal on returning migrants.

For Morocco, the EU disembarkation platform proposal raises questions about the essence of their partnership. Morocco is dissatisfied with the EU’s treatment of the issue because it does not reflect the advanced status the country has obtained since 2008. Questioning Europe’s approach of delegating unwanted tasks to its neighbours, Morocco’s foreign minister has asked: “Are we real partners or just a neighbor you’re afraid of?” Morocco also sees an inconsistency between the EU’s quest for close partnership to tackle migration and terrorism on the one hand, and its tendency to treat the country “like an object” rather than as an equal partner on the other hand. Despite the tension these discussions created, Morocco aims to maintain its cooperation with the EU on migration. Bourita has called for Morocco to be part of EU decisions on migration, prompted perhaps by the lack of consultation with North African countries prior to launching the EU proposal on disembarkation platforms.

***

Morocco has an extensive history of cooperation with the EU and its member states – especially Spain – on migration. But the EU’s proposal to establish regional disembarkation platforms in North Africa did not sit well with the country’s leadership. Morocco’s decision to reject this idea is rooted in domestic and external considerations. On top of this, it holds that such proposals do not reflect the depth of its partnership with the EU. Morocco thus seeks to maintain cooperation with the EU on migration, but refuses to have unwanted tasks delegated to it.

Tunisia

Since 2012 Tunisia has had a privileged partnership with the EU that seeks to deepen cooperation between both sides on a range of issues. These issues include migration through, for instance, the conclusion of a Mobility Partnership. The EU and its member states largely perceive Tunisia as a friendly and relatively stable partner that has a long track record of cooperating on migration issues. However, the country is experiencing worsening economic conditions that leave it in need of EU support and make it relatively susceptible to external pressure. Geographically, Tunisia is not only close to Europe but also borders Libya, making it the country most likely to experience increasing migrant departures by sea as their number in Libyan territory declines. For the EU, these factors make Tunisia an attractive candidate for disembarkation platforms. It comes as no surprise, then, that European politicians and others have argued that Tunisia holds the key to Europe’s migration dilemma.

However, the Tunisian government has not been receptive to these calls. Its ambassador to the EU, Tahar Cherif, said that the EU proposal was “put to the head of our government a few months ago during a visit to Germany, it was also asked by Italy, and the answer is clear: no!” For Tunisia, receiving substantial numbers of migrants and asylum seekers is too risky, especially when the prospects for their swift resettlement or repatriation are so slim. The Tunisian ambassador went on to say that his country does not have the capacity to set up such centres, and that it has already been adversely affected by the fall in departures from Libya. Tunisia has so far kept transit through its territory to a relatively low level thanks to its extensive border security in the south, which makes it challenging for large groups of migrants to enter the country illegally. But this situation could change. Tunisia, therefore, focuses on ensuring there is no spillover into its territory from the situation in Libya, rather than agreeing to intercept migrants’ boats and towing the vessels to its coast. Moreover, striking a controversial deal with the EU when the country is grappling with an internal political crisis could fuel public anger and frustration.

While cooperation with the EU is important for Tunisia, the government does not want to deal with the reputational damage resulting from any such agreement. In 2011 Tunisia accepted thousands of migrants and asylum seekers fleeing Libya in Choucha camp, in southern Tunisia. The government used this “solidarity” to enhance its image abroad and generate international support for its political transition. But a migrant camp to host people intercepted at sea is different, as its inhabitants would not be directly seeking refuge in Tunisia.

The pressure of knowing that the EU would like to get more out of Tunisia on migration has begun to take effect. For instance, in July 2018, the Tunisian government hesitated to allow a private boat that had rescued 40 migrants in the Maltese search-and-rescue zone to dock in Tunisian ports. Denied disembarkation in other European states, the boat stayed at sea with migrants on board for 22 days. The Tunisian government was put in an embarrassing situation, but it was afraid that accepting the migrants could signal to the EU its readiness to bow to pressure and make further concessions. The government eventually said it would accept the migrants on humanitarian grounds. (The migrants then refused to enter Tunisia and threatened to throw themselves overboard before non-governmental organisations intervened to negotiate their safe disembarkation.)

Tunisia appears unlikely to change its position on regional disembarkation platforms any time soon. Indeed, pressure on the country to host a centre like this could undermine its nascent democratic political institutions, and would run counter to the EU’s support for the transition process. Tunisia has a strategic interest in migration cooperation with the EU, but this does not currently align with the EU’s strategic needs. For example, the Tunisian government has attempted to establish a link between ongoing negotiations on a visa facilitation agreement and negotiations with the EU on the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area. It has argued that free movement of goods and services would also require greater freedom of movement for people. But, for the EU, the political climate in Europe does not permit such concessions. These differences in priorities have become increasingly prevalent in EU-Tunisia relations and risk limiting the establishment of shared agendas and approaches.

***

Like Morocco, Tunisia did not react positively to the EU’s proposals for establishing regional disembarkation platforms. On more than one occasion, EU member state politicians proposed Tunisia as a suitable candidate for hosting regional disembarkation platforms (or similar facilities). This is not only because of Tunisia’s proximity to Libya and Europe, but also because it needs the EU’s support more broadly. But the Tunisian government has consistently rejected these proposals owing to its lack of political interest in such a controversial arrangement with the EU. That said, despite challenges in agreeing on shared interests, migration cooperation with the EU remains important to Tunisia.

Algeria

Like Morocco, Algeria is a country of origin, transit, and destination. According to recent estimates, Algeria may host between 25,000 and 100,000 migrants from sub-Saharan African countries. The EU is keeping its options open as to which countries might host regional disembarkation platforms, but Algeria emerges is a particularly unlikely candidate. Like its neighbours, Algeria rejected the possibility of hosting a disembarkation platform. Earlier this year, Algeria’s foreign minister, Abdelkader Messahel, commented that Algeria faces the same migration problems as Europe, and that his country is steering its efforts towards working with countries of origin on repatriating their nationals. From the Algerian (and the Moroccan) perspective, Europe has the capacity to deal with this problem.

Important to the Algerian government’s stance is its “strong claim to sovereignty” and its sensitivity to external interference, which stems from its colonial history. Unlike its neighbours, Algeria does not see itself as a key interlocutor of the EU on migration, beyond some cooperation on border management and the return of its nationals. For these reasons, the country’s cooperation with the EU on migration remains relatively underdeveloped. For example, Algeria does not have a Mobility Partnership with the EU that could serve as a general framework for dialogue on migration. Cooperation with the EU on border security and migrant returns remains selective and limited in comparison that of Morocco or Tunisia.

Instability in neighbouring Libya has affected Algeria: job prospects previously on offer in Libya for sub-Saharan African migrants have now disappeared, leading many more migrants to travel to Algeria instead. Rising numbers of migrants and shifting movement patterns have also had an effect. For instance, in the past, migrants would largely remain in border areas, but many more now make for coastal cities. As sights of foreign migrants begging in the capital and other large cities become more common, complaints and concerns about the newcomers have grown accordingly: in June 2017, a campaign called “No to Africans in Algeria” went viral. A counter-campaign was soon launched by Algerians denouncing the claims as racist and reminding their compatriots of Algerians’ African identity.

The government’s response has been mixed; at one point, an official added fuel to the fire by accusing irregular migrants of spreading HIV. Shortly after, however, it shifted its approach, adopting a more balanced approach by announcing a regularisation campaign for migrants to fill job shortages in construction and farming. The flipside to this is that the government has forcibly repatriated thousands of migrants not granted a work permit. Furthermore, the Algerian authorities have been accused of leaving more than 10,000 migrants in the desert, forcing them to walk across the border to Mali and Niger.

Indeed, despite Algeria’s active presence at the AU, the country’s handling of the migration challenge suggests that it has little concern for how such actions could damage its regional standing. In one incident, a group of Malians who were forcibly returned from Algeria attacked the Algerian embassy in Bamako to protest the difficulties they faced during the process. While Algeria’s regularisation campaign could signal an attempt to attenuate its security-driven approach to migration, the government has rejected any criticism of its crackdown on irregular migrants as attempts to tarnish the country’s image abroad. Foreign policy considerations are, therefore, unlikely to shape its position. Yet the government’s preoccupation with security could – unintentionally – overlap with the EU’s interest in border security, furthering the latter’s objective of stepping up cooperation on border management with Algeria.

***

Like its neighbours, Algeria has rejected the possibility of hosting regional disembarkation platforms. Algeria contends that it is grappling with the same migration challenges as the EU and that the latter has the required capacities to manage the situation. And the primacy of security interests and growing domestic anti-migrant sentiment have contributed to shaping the Algerian stance on this issue. Algeria’s position is particularly unsurprising in light of the country’s limited cooperation with the EU on migration and its lack of interest in developing this cooperation.

Alternatives to regional disembarkation platforms

Politics and practicalities have together put paid to EU plans to establish regional disembarkation platforms in North Africa. The EU does, of course, retain the option of pursuing two other tried and tested forms of cooperation with its North African partners: border management, and the repatriation of irregular North African migrants in Europe. Border management and migrant return have always featured strongly in EU-North Africa cooperation on migration. Despite their track record of joint work in these areas, underpinned by an arsenal of bilateral agreements, cooperation has not been devoid of tension, especially on migrant return. Border management, meanwhile, broadly represents a mutual interest of Europe and its southern partners, but even the success of this depends on several variables.

Border management

Rather than acceding to demands to tow migrant vessels to their shores and host them in regional disembarkation platforms, Maghreb countries are interested in further financial and logistical assistance from the EU to secure their borders and reduce migrant inflows. Like Europe, they feel pressure on their borders and want to prevent migrants from either entering and working in their territory or travelling on to European countries. Maghreb governments are candid about the benefits they hope to gain from working with Europe on border management: according to one Moroccan official, the current regional environment means that Morocco needs EU support to “cope with the increasing pressure”. Indeed, Europe-North Africa cooperation on border management has a reasonable pedigree, going back the 1990s with the establishment of the Western Mediterranean Forum, known also as 5+5 dialogue. The forum brings together five countries from Europe (France, Italy, Malta, Spain, and Portugal) and five Maghreb countries (Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, Libya, and Tunisia). Cooperation has grown since the establishment of the forum.

The EU seeks to involve these Maghreb countries in its border management system by making as much use as it can of existing cooperation frameworks and encouraging its neighbours to work with border authorities in southern European countries. The EU and its member states seek to step up training, logistical, and technical support for coastguards in North African countries. These objectives have been at the centre of diplomatic visits and talks between the sides, though neither has pursued them with great urgency.

With support and financing from the EU, for instance, Morocco and Spain engage in advanced cooperation involving joint patrols and the use of high-tech surveillance systems – including radars, satellites, and drones – to intercept irregular migrants. This joint work often wins praise from both sides. Morocco also participates in the Seahorse Atlantic Network, a communication and information exchange system that links border authorities in countries on the Mediterranean and west African coasts to enhance cooperation between them. Morocco also works with Spain on the securitisation of the land borders of the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, whose multiple fences are equipped with high-tech surveillance systems – although these have not stopped mass border crossings.

One of the current objectives of the EU and its dialogue on migration with Algeria and Tunisia is to persuade them to join the Seahorse Mediterranean Network. The network is a “secure communication platform” that allows participants to share information in an efficient way, with no obligation to exchange information or engage in joint patrols. The objective behind the network is to enhance the exchange of information between not only North African countries and EU member states but between countries on the southern shore of the Mediterranean. However, these countries have evinced little interest in doing so. For its part, Algeria has signalled to the European Commission that it has no interest in participating in this network. In addition, the EU recently suggested that Tunisia take part in the network and attend training sessions for it without formally committing to participate in the project. The Tunisian authorities are yet to reply to this offer. Reluctance to participate in the network may result from concerns that these working arrangements could lead to stronger involvement in EU’s border control systems and to regulations that allow the EU to patrol their territorial waters. Moreover, a country such as Tunisia may be concerned that it would be investing its already limited security resources in issues that are not priorities for it.

On a more productive front, following a Spanish request to the European Commission last summer, cooperation between the EU and Morocco is set to increase through a new support package of €140m for enhancing the country’s border controls. Half of the funds will be used to buy border control equipment, while the rest will come in the form of budgetary support. The EU seeks to deepen this sort of collaboration with Morocco and other countries in North Africa through Frontex, the European border agency. With the exception of Algeria, North African countries deal with Frontex in the context of, for example, return operations coordinated by the agency. Seeking to involve North African countries with Frontex in a more structured way, the EU has mandated the agency to negotiate working arrangements with several third countries, including Tunisia and Morocco. These working arrangements aim to secure the partner country’s participation in joint operations such as joint return flights, training programmes, and information exchange and risk analysis. The Frontex Management Board has had a mandate to negotiate a working arrangement with Tunisia since 2011, but there has been no substantial development in the talks despite repeated EU attempts. Negotiations between the board and Morocco halted when dialogue at the political level stalled.

Having engaged in advanced cooperation with Morocco, the EU seeks to build a similar relationship in border management with other countries in North Africa. The EU announced that it will deepen dialogue with, and provide further assistance to, Tunisia, Algeria, and Egypt on border management. In Tunisia, this dialogue on migration takes place within the Mobility Partnership, which the EU says has “reinforced dialogue and brought better management of operational and financial support” and allowed “relations in this area [to] be taken to a new level”. EU and member state politicians have called for more support for Tunisia’s border control capabilities.

Of the three Maghreb countries, Algeria remains the least engaged with the EU on border management. Discussions with Algeria on a Mobility Partnership that could serve as a general framework for dealing with migration, including through advanced cooperation on border management, have not progressed. Besides, as noted above, Algeria has no interest in engaging with Frontex or joining the Seahorse Mediterranean Network. The EU has been keen to work with Algeria on migration in relation to the risks that inadequate border controls pose to the country’s security, but the Algerian authorities have generally avoided strong commitments in the area. This hesitation likely relates to concerns about sovereignty and to a distrust of Europe, which often leads Algeria to dismiss proposals for cooperation from the EU as attempts to interfere in the country’s internal affairs.

***

A recurrent challenge for EU-North Africa cooperation stems from the fact that border management is not a standalone issue. There have been periods in which suspicions have arisen that North African counties allow migrants to travel northwards as a bargaining chip in their wider relationship with the EU. One observer reports that rising migration from Tunisia since mid-2017 led “many EU officials [to begin] to wonder what message Tunisian authorities were trying to send to them.” This sudden increase was even more puzzling because it could not be traced back to the closure of the Libya route: the vast majority of migrants leaving from the Tunisian coast are Tunisians. But attributing such increases to a deliberate strategy by the government risks excluding the driving factors that propel this migration movement and could undermine the border management challenges North African countries face. Rising sea crossings from Tunisia also coincided with increasing arrests of smugglers and migrants before they left the Tunisian coast. The number of migrants arrested before leaving the coast increased from 1,035 in 2016 to 3,178 in 2017. This indicates that the Tunisian security forces increased their efforts to limit the flow of migrants but their work was curtailed by limited capacity, a lack of equipment, and increasing external pressure – as suggested by the shipwreck off Tunisia’s Kerkennah islands in June 2018. At the time of the accident, there had been no decision to establish a security centre at Kerkennah and security offices damaged during the 2011 revolution had not been repaired. Nonetheless, the authorities launched an investigation into possible complicity between some security officials and smugglers. While these developments suggest that the Tunisian government is not strictly enforcing border controls, there is little evidence to suggest a deliberate effort to send a political message to Brussels.

The broader truth is that, unlike European states, North African countries simply do not view preventing migrant departures as a top priority, or even an urgent issue. There is no significant cooperation between the sides in the area. But it is also the case that migrant movements into Europe can alleviate domestic pressure on North African governments. Still, it remains important for them to secure their countries’ borders and to demonstrate that they are capable of doing so. While these differences in perceptions and priorities have often been a source of tension in the relationship, North African countries’ interest in preserving it and preventing the issue from dominating their bilateral talks could push them to engage more actively in this and increase the importance of the topic domestically. Thus, cooperation between the EU and North African countries on migration issues may well increase – not least because border management remains the least controversial aspect of such efforts.

Migrant return

European leaders are intent on bolstering cooperation with North African countries, in the hope that they will accept the return of more irregular migrants from the EU. Seeking to achieve results swiftly, EU member states have engaged in talks with these countries on how to enhance collaboration. There are two areas of return: the return of North African nationals from Europe to North Africa; and the return of third country nationals – namely, migrants who transited through North African territory but who did not originate there – to North Africa.

While North African countries remain generally willing to engage with the EU on the return of their nationals, they resist cooperation on the readmission of third country nationals. Indeed, the EU has been in negotiations on this with Morocco since early the 2000s. These negotiations made little progress and were suspended in 2010, resuming only with the signing of the Mobility Partnership in 2013. Negotiations with Tunisia began in 2016 following the signing of the Mobility Partnership in 2014. The inclusion of a clause on the readmission of third country nationals in agreements with both countries has hampered ongoing negotiations (though this is not the only contentious issue in the discussions). In the case of Tunisia, for example, key arguments against the inclusion of such a clause centred on the low level of transit through the country and the lack of regularisation policy and voluntary return programmes to deal with returnees. Meanwhile, Morocco perceived this clause as calling for an “inequitable” division of responsibility. Both Morocco and Tunisia also raised several technical questions about, for example, the proof of transit to be used.

The EU and its member states are intent on finding more practical ways for third countries to accept the return of North African citizens. This includes leveraging EU visa policies, linking visas more closely to how cooperative on returns a country is. In this context, in March 2018 the European Commission proposed a reform of the EU common visa policy. This would include enhancing the EU Visa Information System (VIS), a database that collects information on foreigners who apply for Schengen visas (such as fingerprints and copies of travel documents) and that connects EU border guards with EU consulates abroad. The EU’s objective is to achieve even more thorough background checks on visa applicants, seeking to prevent the infiltration of “criminals and potential terrorists” into the EU. Equally importantly, thorough collection of information about visa applications, including applications that can be rejected, would allow the EU to swiftly return these individuals if they intended to illegally travel to Europe; it would also enable the EU to return those who arrived legally but overstayed their visas. These measures would reduce the need for countries of origin to identify their nationals, even if they were still to ask to check the information held by Europeans. While the VIS originally only collected information about applications for short-stay visas, it will now also cover long-stay visas and residence permits.

In the same context, the European Commission is seeking to put in place a new mechanism to allow stricter application of visa restrictions if a country is unwilling to cooperate on the return of migrants, including those who entered legally but overstayed their visas. More restrictive application of the visa code could include, for example, extending the period required to assess a visa request, the period of the validity of the visa issued, visa fees, and travel restrictions for some people, such as diplomats. For North African countries, these proposals would also mean more cumbersome and lengthy procedures for visa applicants.

Besides these ongoing efforts on the EU side, individual member states have also stepped up their bilateral talks with southern partners on returns. For instance, migrant return has become a priority in Germany’s approach to talks on migration with North African countries. Seeking to expedite the deportation of rejected asylum seekers who are nationals of Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco, in 2017 the German government unsuccessfully attempted to pass legislation to classify these three Maghreb states as safe countries. The upper house blocked the plans, but the government is putting the proposal back on the table. In the meantime, it is intensifying its talks with these countries with a view to making repatriation more efficient. In September 2018, Angela Merkel visited Algeria and secured a commitment from its government to return the 3,700 Algerians known to be irregular migrants in Germany. This followed closer collaboration on migrant return by the Algerian side over the previous two years. But, following Merkel’s visit, Algeria announced its further commitment to return another group of 700 Algerian nationals residing illegally in Germany, though it did not specify a time frame for this.

While, in principle, Algeria has engaged in cooperation on returns, the implementation of its agreements with Germany might not be as efficient as Berlin hopes. Many European countries say they have successfully returned migrants to Algeria, but most also experience delays and difficulties in the identification of migrants and the issuance of required travel documents. Besides, Algeria is unwilling to accept some return mechanisms: for instance, it rejects the use of charter flights for collective return operations and accepts only commercial flights. It also does not accept joint return operations coordinated by Frontex. This presents a challenge for countries hosting significant numbers of irregular Algerian migrants, as it makes it possible to send back only one or two migrants per flight. Probably to speed up the return of the group of 700, the Algerian authorities suggested that Lufthansa should be involved in the return operations, along with the Algerian flag carrier.

Like Germany, Italy also intends to find workable arrangements and secure even stronger cooperation on returns from North African countries. In September 2018, Tunisia became the first Maghreb state Italian interior minister Matteo Salvini travelled to for an official visit; Tunisia ranks high on the Italian agenda. Italy and Tunisia developed an oft-hailed functional cooperation arrangement on migrant returns that dates to the 1990s, when Italy first imposed visa restrictions for non-Europeans. The first readmission agreement between both countries was signed in 1998. This cooperation agreement has become stronger since 2011, as more than 28,000 Tunisians used the lax security situation at the border to flee the country within the first few months following the ouster of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali from the presidency. This mass migration from the country placed growing pressure on the successive fragile governments in Tunisia to restore border security and enhance migration cooperation with the EU and its member states. Tunisians constituted 35 percent of the total number of repatriations by Italy in 2015, rising to 43 percent in 2016. Deportation procedures were further enhanced in 2017: the weekly quota for migrant removals was doubled by agreeing on two deportation charter flights, each carrying 40 migrants per week. During his visit to Tunisia, Salvini expressed a wish to further increase these quotas. His attempt, however, was not successful. The Tunisian government promised to strengthen bilateral cooperation and enhance its border controls instead. Italy, for its part, pledged to increase economic and training aid to Tunisia.

Morocco too is under increasing pressure to return its nationals. In Spain, the Andalusian authorities are pushing the national government to activate a 2007 bilateral agreement with Morocco to return migrant minors, to alleviate pressure on its overcrowded centres. The government of Melilla has made the same request. Seventy percent of the 7,000 migrant minors currently in Spain originate from Morocco. According to some media reports, Spain is undertaking talks with Morocco on the possible repatriation of these minors. Spain’s secretary of state for migration has stated that Morocco is willing to push these talks forward, but the sides do not appear to have made concrete plans thus far. In a broader sense, countries of origin are generally uncooperative on returning minors as this provokes controversy among human rights groups such as Save the Children. Legally speaking, such returns are not problematic as long as the Moroccan authorities guarantee that the minors are returning to a safe environment.

For Spain, returning migrants, Moroccan or otherwise, is increasingly important. This is clear in its intent to fully implement existing bilateral agreements with countries of origin and transit, such as its 1992 readmission agreement with Morocco, which was activated in 2012 and “provides for minimal formalities to facilitate the return of third country nationals”. In 2018, Spain twice resorted to this agreement to swiftly return third country nationals to Morocco. However, swift removals are rare. In these cases, Morocco accepted the express deportations because of what it called “good bilateral relations”. Indeed, the implementation of such bilateral agreements often depends, among other things, on the state of the relationship between the sides at the time.

North African countries regularly state a willingness to readmit their citizens, provided they go through the necessary procedures to identify the migrant and issue their travel documents. But the process usually has mixed results, as there are other factors in play. Firstly, remittances contribute to the economy in countries of origin and provide a source of income for the families of North African migrants regardless of whether they are regular or irregular migrants. Secondly, governments are concerned about returnees becoming an economic burden. And returnees often have to contend with the social prejudice of coming back “empty-handed”, especially after several years in Europe. It is probably due to these considerations that the Tunisian government usually prefers to conduct return operations under the radar. In Tunisia, migrant return is hardly discussed in the media, even as incidental news. All charter flights carrying deported migrants land at Enfidha airport, away from the busier Tunis airport. In one of the few media reports on the condition of Tunisian migrants awaiting deportation in Italy, a Tunisian delegation that was in Rome to discuss irregular migration and readmission refused to speak to journalists.

Such trade-offs are likely to influence the decisions of North African countries on migrant return, especially forced return. Countries sometimes resort to blocking forced return by not issuing the travel documents needed to deport a migrant. For example, EU member states such as Hungary have noted that, while the Algerian authorities are generally collaborative on voluntary return, they are sometimes less so when the return is forced. If an Algerian national has an EU child or spouse, or is engaged to a national of the EU member state, they may refuse to issue a travel document or delay the process for social or humanitarian reasons. There are limits to what North African countries are willing to accept. For instance, in the context of negotiations on a readmission agreement launched in 2016, Tunisia rejected an EU proposal to grant a laissez-passer to return Tunisian migrants should there be a delay in the Tunisian authorities issuing their travel documents. The authorities argued that such a measure would undermine the sovereignty of their country.

Migrant return is likely to become even more important in EU-North Africa cooperation, especially in light of the EU’s pursuit of a more coherent and efficient return policy. The growing pressure on North African countries to actively work with the EU on various aspects of migration management means they are likely to step up their cooperation on the return of their nationals. That is, they are more likely to be responsive to European requests on relatively unproblematic issues to signal their commitment to the EU and dissuade it from pushing further on controversial proposals such as regional disembarkation platforms.

Conclusion

The migration crisis of the mid-2010s has ensured that migration is an increasingly dominant issue in EU-North Africa cooperation. When Libya was the main point of transit to the EU, it became the principal focus of European policies. Now, effectively closing the Libyan route has displaced migration flows towards other countries. The impact of this rerouting was quickly felt in Morocco and Algeria. Today, the same challenge confronts all countries in North Africa: pressure on their land and maritime borders is growing, as are domestic politicisation and securitisation of migration. To some extent, these trends have been induced by EU and member state policies. In new attempts to prevent flows from reaching Europe, the EU and member states are now dangling new migration deals in front of North African countries: host migrants in return for attractive financial packages, they say. But there is little clarity about the precise benefits North African countries can gain from such arrangements.

The EU’s concerns about irregular migration are justified: the issue now features prominently in the politics of many member states, and the EU is under pressure to demonstrate that it can control its borders. Even if the number of sea crossings has substantially decreased, migration will continue to dominate the public debate in Europe, not least because populist parties will continue to instrumentalise it to win popular support. The rise of far-right parties endangers the survival of the EU itself.

However, the EU’s proposal for regional disembarkation platforms was likely a misstep: it created tension and fuelled distrust between the sides. Irrespective of the degree of their – often already extensive – cooperation with the EU on migration, North African states did not welcome the proposal. Their position has been shaped by a combination of political and practical concerns about the implementation and likely impact of these platforms. Significantly, both parties face similar issues in this area – North African countries have to contend with domestic discontent about migration just as much as European countries do, if not more so. However, the solutions to these strategic challenges the EU has devised thus far do not meet the needs of either side.

The Europeans appear to have set aside their proposal for regional disembarkation platforms – for now. It may yet return to the mix, however, as North African states consider their options and Europe remains intent on keeping migrants away from its shores. North African countries are nominally strategic partners of the EU; but their perception that Europe is sloughing people off onto them has offended governments in the region that value their sovereignty. They also do not understand why Europeans would play a role in injecting potential instability into North African countries, nor why they cannot simply at least mitigate the problem by concluding agreements with sub-Saharan countries such as those they have long maintained across the Maghreb. Even public debate about this topic can threaten countries’ stability, as local populations keep a wary eye on what their governments appear open to agreeing with Europe. Countries such as Tunisia are especially vulnerable to this; stirring up such debate contradicts the EU’s investment in, and support for, Tunisia’s transition process.

Despite the current difficulties in migration talks, the EU could overcome divisions between the sides by avoiding controversial proposals that are likely to undermine North African countries’ interests and priorities. There remain enough – perhaps only just enough – converging interests for the parties to conclude that cooperation can be both desirable and feasible. As a matter of principle, North African countries are willing to cooperate with Europe. They are especially willing to cooperate on border management, as this represents a significant overlap with their interest in enforcing internal security. Moreover, it is not in their interest to allow the entry of irregular migrants that may never leave. The situation in Algeria clearly demonstrates that there is both official and public demand for addressing this challenge. Most countries in North Africa are likely to welcome transfers of logistical and technical assets to counter smuggling networks. However, both sides should be careful not to engage in security-only approaches. Pressuring countries to fully engage in the EU’s border control systems might not be the right approach, as this hinders the development of a joint agenda and risks turning countries in the southern neighbourhood into mere facilitators of the EU’s agenda.

On readmission, all North African countries have demonstrated an in-principle commitment to assist with the return of their nationals from Europe, even if there are differing levels of cooperation between them and EU member states. That said, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia could all play a more proactive role in ensuring the speedy and fair readmission of their citizens. The EU could assist with reintegration programmes, which make returns more sustainable by dampening motivations for new departures. It should also move quickly to address obvious shortcomings such as the inhumane treatment of migrants in Italy before deportation and the lack of support for reintegration. Otherwise, these poor conditions may motivate migrants to attempt to cross the Mediterranean again. That said, while these measures are important, only viable economic opportunities will persuade marginalised young people to stay in their countries.

Looking ahead, migration will be high on the agenda for the upcoming EU-League of Arab States Summit in early 2019 and for Emmanuel Macron’s Mediterranean Summit in Marseille, scheduled for July 2019. As the issue of migration is growing only more salient on both sides of the Mediterranean, these summits provide an opportunity to clearly define areas of mutual interest where there is potential for cooperation. Europe and North African countries need to take the interests and priorities of each other into consideration if they are to form a joint agenda and deepen their cooperation. If they do not, the migration “crisis” in Europe could become a crisis of trust and of renewed instability around the edges of Europe – one which benefits nobody.

About the author

Tasnim Abderrahim is a visiting fellow with ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa Programme where she focuses on migration in EU-North Africa relations. She previously worked as a junior policy officer at the European Centre for Development Policy Management in Maastricht and as a Research Assistant with the Centre des Etudes Méditerranéennes et Internationales in Tunis.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Chloe Teevan and Julien-Barnes Dacey from ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa programme as well as Jeremy Shapiro, Anthony Dworkin, and Shoshana Fine for their comments on drafts of the paper. The author would also like to extend thanks to Adam Harrison for editing the paper and creating the graphics.

ECFR would like to thank Compagnia di San Paolo for their support for this publication.

Graphic sources

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.