A return to Africa: Why North African states are looking south

Summary

- North African countries, each for their own reasons, are increasingly turning their attention towards sub-Saharan Africa.

- Morocco is pursuing a comprehensive campaign to increase its influence and win support with regard to Western Sahara.

- Algeria may be showing new flexibility in its response to security threats to its south.

- Tunisia is beginning to look for new economic opportunities in Africa.

- Egypt is responding to a series of strategic concerns, particularly over the waters of the Nile.

- Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia are also all dealing with increased migration flows, with migrants seeking to work on their territories or pass through it to reach Europe.

- This North African turn to sub-Saharan Africa offers opportunities for European cooperation. But the EU should be aware of the distinctive agendas of North African countries and the reservations that their initiatives engender in some countries.

Introduction

European policymakers have generally looked at North Africa through a Mediterranean lens. Since at least the Barcelona process of Euro-Mediterranean partnership was launched in 1995, European nations have seen the countries on the Mediterranean’s southern shore, from Morocco to Egypt, primarily in the context of their own neighbourhood. Behind this approach rests a history of close links stretching back through the colonial period as well as deep economic relations; Europe is the most important trading partner and investor for the majority of these countries.

But this vision of North Africa, which was always too simplistic, is increasingly at odds with the reality of how these countries see themselves. Across the region, North African countries are turning their focus towards their own continent and stepping up their engagement with sub-Saharan Africa.

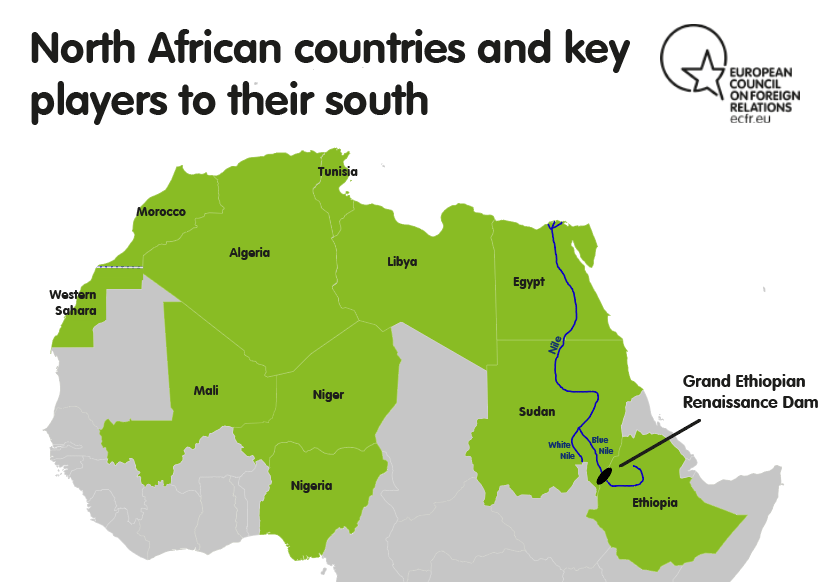

The North African turn towards Africa is driven by several factors. Some countries are engaged in an effort to win diplomatic support on significant questions of national interest: for Morocco and Algeria, the dispute over Western Sahara and their broader strategic rivalry; in the case of Egypt, its concern about the giant dam that Ethiopia is building on the Nile. Beyond this diplomatic effort, the focus is also a response to the rising security threats and flow of migration reaching North African countries from the south.

Finally, the shift is driven by economic concerns. North African countries are searching for new markets and seeking to position themselves for the economic and demographic growth expected in sub-Saharan Africa in the coming years. This has been given new impetus by the continuing slow growth rates of North Africa’s traditional European trading partners. The turn to the south is also a reaction to the failure of regional integration within North Africa, where trade between countries remains low. Economic and political cooperation, for example through the Arab Maghreb Union, is held hostage in particular to the Algerian-Moroccan stand-off over Western Sahara.

The impact of covid-19 is likely to impose some short-term limitations but also offer new areas of focus for this process. At the time of writing, Africa has seen a lower death toll and infection rate than other continents, with 8,630 reported deaths. Many African countries have responded effectively and innovatively to the crisis. Nevertheless, the peak of the disease may not yet have arrived in Africa. In any case, the economic and social impact of the coronavirus on the continent is likely to be profound, with widespread job losses, difficulties in meeting debt payments, and a possible food crisis. At the same time, these effects could spur a transformation of African economies towards greater self-sufficiency, including in the production of food and medicines. They could also lead to a bigger emphasis on renewable energy and greater digitalisation. Such a transformation could offer further opportunities to those North African countries that have well-developed technology, health, and renewable energy sectors.

At a time when the EU is also seeking to deepen its relationship with sub-Saharan Africa, based around a joint communication of the European Commission and the High Representative unveiled in March 2020, the North African turn southwards deserves greater European attention. EU policymakers could benefit from understanding North African engagement in sub-Saharan Africa in two ways. Firstly, they should recognise that North African partner countries have their own policy agendas in areas like migration, trade, and investment that are not directed towards Europe, and that EU-North Africa cooperation will be more successful if it takes this into account.

Secondly, an understanding of North African strategies could also lead to a greater awareness of where Europe and North African countries could cooperate in sub-Saharan Africa. However, even as they look for synergies, Europeans should also remember that not all North African initiatives are welcomed, or accepted at face value, by sub-Saharan countries. Europeans should be aware that accepting North African offers of triangular cooperation may in some cases have drawbacks that outweigh the advantages they offer.

This policy brief offers a stock-take of the African strategies of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Egypt. It excludes Libya – which had an intensive engagement with sub-Saharan Africa and with the African Union (AU) in the years before 2011 – because the political crises and civil war that the country has witnessed in the last few years have left it unable to pursue any far-reaching African strategy at the state level for the moment.

Morocco: Rejoining “the family”

Morocco rejoined the AU in January 2017 after an absence of 33 years. The step was a key symbolic moment, illustrating the determined way that the country has tried to reinforce its ties with sub-Saharan Africa in recent years. Morocco had quit the AU’s predecessor, the Organisation of African Unity, in 1984 to protest against the body’s admission of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) as a member. The SADR is the state declared by the Polisario Front in the former Spanish colony of Western Sahara, which Morocco claims as its territory and most of whose territory it controls. Morocco regards the dispute over Western Sahara as a vital question of national interest. Its return to the AU represented a shift in its strategy to win backing for its control of the territory.

But Morocco’s ambitions in sub-Saharan Africa extend beyond the search for support over Western Sahara. It also has economic and security goals, and is seeking to establish itself as a major player on the continent. King Mohammed VI said when Morocco rejoined the AU: “At a time when the Kingdom is among the most developed African nations … we have decided to join our family again.”

Morocco’s decision to enter the AU without securing the SADR’s expulsion marked a recognition that its “empty chair” approach was not working. After Morocco’s readmission, the AU agreed in July 2018 to set up a troika consisting of the current AU chairperson as well as the previous and incoming chairs. This troika aims to support the UN process on Western Sahara, and effectively removed the subject from discussion in the AU’s Peace and Security Council (PSC) in Addis Ababa by kicking it up to head of state level. This move bracketed AU disagreements on Western Sahara but did nothing to resolve them. The AU remains “blocked” on the topic. At the same time, Morocco has made little secret of its ultimate ambition to force the SADR out of the AU.

Morocco has also continued to try to normalise its control of the territory by persuading African countries – primarily, but not entirely confined to, its traditional francophone supporters – to open consulates in the territory. Ten have done so in recent months. Nevertheless, South Africa, Algeria, Kenya, and other influential African countries continue to support the Polisario Front and uphold the AU’s traditional position in favour of the right to self-determination of the Sahrawi people.

Morocco’s diplomatic push on Western Sahara has been matched by an economic drive to expand its investment and business operations in Africa. Since Mohammed VI became king in 1999, he has made a series of high-profile visits to African countries. These include business delegations and the visits are often accompanied by the announcement of large-scale investments. Between 2003 and 2017, Moroccan foreign direct investment in Africa totalled 37 billion dirhams (roughly €9 billion), making up around 60 per cent of the country’s overseas investment. By 2017, Morocco had become the leading African investor in West Africa and was second only to South Africa as the largest African investor across the continent as a whole.

Investments have been particularly concentrated in the banking and telecommunications sectors, led by large enterprises such as Attijariwafa Bank, Banque Centrale Populaire, and Maroc Telecom. Initially focused on Morocco’s traditional West African francophone allies like Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire, the country has more recently expanded the range of its investments. Among other agreements, the phosphate conglomerate OCP signed a deal for a giant fertiliser production plant with Ethiopia in 2016. In the same year, Morocco also agreed a major project to build a gas pipeline from Nigeria to its Mediterranean coast.

Morocco’s increasing ties with non-francophone African countries that have traditionally opposed its policies on Western Sahara reflect a shift in the continent from ideological to more pragmatic approaches, according to African analysts. But there is still a good deal of suspicion of Morocco’s ambitions in Africa. This has been evident particularly in the reaction to Morocco’s application in 2017 to join the 15-member Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). West Africa absorbs the majority of Moroccan exports within Africa, yet, since goods from Morocco still make up only a small proportion of West African imports, there is evidently room for Morocco to expand its market share.

However, although Morocco’s bid was approved in principle in 2017, progress towards full membership has stalled. The question was not even on the agenda at the two most recent ECOWAS summits. Some ECOWAS members are worried that Morocco’s competitive economy could lead to the erosion of domestic manufacturing, and that Morocco’s free trade agreements with the EU and the United States could open a “back door” for goods from these regions to enter West Africa. West African economic lobbies see the bid as “a predatory move by companies in the kingdom to compete unfairly in their markets”. There is also concern among anglophone West African countries that Morocco’s accession could undermine the position of Nigeria, the dominant country in ECOWAS, and tilt the balance of power in favour of the francophone group of countries within ECOWAS. Finally, many ECOWAS member states question whether Morocco is ready to implement the provisions allowing the free movement of people across the bloc.

Morocco’s Africa strategy also incorporates a large soft power element, based around development cooperation, education, and religious training. According to Mohamed Methqal, the head of the Moroccan International Cooperation Agency (AMCI), Morocco’s “long history of links with the rest of the continent means it is well placed to help other African countries replicate the development story of Morocco”.[1] Through its cooperation agency, Morocco has developed partnerships with 46 other African countries. It provides both humanitarian assistance and capacity building in a range of development fields, including public administration, health, education, power generation, and rural electrification. Morocco has focused particularly on bringing students from across Africa to the country for higher education; since 1999, 23,000 students from Africa have graduated from Moroccan universities or technical programmes, and 11,000 were registered in 2018-19, with most receiving Moroccan financial support.

Morocco has also focused on religious diplomacy and education, drawing on the country’s moderate tradition of Islam and the traditional networks of Sufi orders such as the Tijaniyya, which link Morocco and West Africa. In 2015, Morocco established the Mohammed VI Foundation for African Ulema to promote a tolerant vision of Islam among partner countries, with an emphasis on West Africa. It has also trained hundreds of African imams in Morocco through the Mohammed VI Institute in Rabat. In the words of one analyst, Morocco’s religious diplomacy is now a structured and comprehensive policy that aims to build on the Moroccan-African joint spiritual heritage “in consolidating the establishment of long-term vital strategic partnerships with African countries”. Moroccan officials also argue that the programme plays a security role, helping provide a counterpoint to Islamist radicalisation in the Sahel, and represents a distinctively “soft” alternative to the counter-terrorist approach that Morocco’s arch-rival Algeria has promoted through the AU. At the same time, Morocco has also offered training and financial support to members of the G5 Sahel joint force, a French-backed security initiative in which Algeria does not participate.

Finally, Morocco has attempted to position itself as a leader in Africa on the topic of migration. King Mohammed VI was given a lead role on migration issues within the AU and in 2018 Morocco secured AU agreement to host a new African Observatory on Migration, which will track migration dynamics and coordinate government policies on the continent. Morocco’s approach to migration can be seen as an attempt to turn a complex policy challenge to its advantage. Long a source of migrants itself, Morocco has also become a transit and destination country for migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, with the number of immigrants rising from 54,400 in 2005 to 98,600 in 2019, according to government figures.

Eager to show itself as a reliable partner for Europe in restricting irregular migration from its territory to the EU, Morocco has also tried to move beyond a repressive approach. Following past accusations of violating migrants’ rights and evidence of racism towards African migrants in Moroccan society, the country launched a comprehensive migration reform drive in 2013 and has offered legal status to nearly 50,000 migrants, most of them from sub-Saharan Africa. Nevertheless, there is evidence that Morocco continues to face difficulties in integrating African immigrants and offering them economic opportunities, and there may be a risk that these problems could come to damage relations with sub-Saharan countries.

The Moroccan authorities like to say that their growing engagement with Africa presents an opportunity for Europe. Mohamed Methqal of AMCI argues that Europe’s future depends on sustainable development in Africa and that the EU should partner with Morocco to promote this, since the country “has relevant expertise that is adapted to local realities”.[2] Morocco also promotes itself as an economic bridge between Europe and Africa, and established the Casablanca Finance City to offer international firms a base for operations on the continent; Casablanca is now ranked as the leading financial centre in Africa. In many areas of development, such as renewable energy or health, there may be advantages in coordinating international cooperation. But Europeans should also recognise that Morocco’s strategic agenda in sub-Saharan Africa is, unsurprisingly, geared towards its own interests and complex relationships, and that its engagement with African partners involves continuing tensions as well as goodwill.

Algeria: The pursuit of lost influence

Algeria has a long history of ties with sub-Saharan Africa. Following its independence in 1962, Algeria became a beacon of inspiration to anti-colonial and revolutionary movements across the continent. During the 1990s, the Algerian civil war lowered the country’s diplomatic profile. But by the early 2000s, Algeria had regained influence in Africa, particularly within the AU and on issues of peace and security. Algeria built on its own experience of the “black decade” to position itself as a leader in confronting international terrorism.

Algerian officials played an influential role in designing the African Peace and Security Architecture that underpins the AU’s security policy. Algerians have also occupied the key role of AU Commissioner for Peace and Security continuously since the AU was set up in 2002. The first two holders of the office were Saïd Djinnit and Ramtane Lamamra, two of Algeria’s most senior and internationally recognised diplomats. Algeria hosts the Africa Centre for Studies and Research on Terrorism and ensured that counterterrorism was included as one of the areas of responsibility of the PSC. Beyond security, Algeria was also central to the setting up of the AU’s New Partnership for Africa’s Development in 2002. Algerians’ confidence of their influence within the AU led one diplomat to claim in 2012: “Algeria can sway the AU in its direction without, however, putting great pressure.”

In recent years, however, Algeria’s influence across the continent has weakened. After President Abdelaziz Bouteflika was largely incapacitated by a stroke in 2013, his engagement with other African heads of state faded away and Algeria’s bilateral ties with sub-Saharan countries were eroded. Guided by a vision of national self-sufficiency, Algeria chose not to set up a sovereign wealth fund that could purchase overseas assets with the revenues from its gas and oil reserves. The fall in hydrocarbon prices after 2014 then dealt a major blow to Algeria’s economy, but any hopes of diversification through expansion into African markets were limited by regulations that constrained overseas investment. Under rules that were updated in 2014, private companies are only allowed to invest abroad for activities that are complementary to their domestic business, and transfers of capital still require official authorisation.

A high-profile conference organised in Algeria in 2016, the African Forum for Investment and Business, was overshadowed by feuding between members of the elite, as the prime minister, Abdelmalek Sellal, walked out in protest at the role taken by the influential businessman Ali Haddad. Nevertheless, some observers believe the forum helped lay the ground for increased commercial ties in the future.

Algeria has long seen itself as playing a dominant role in the Sahel, but here too its place has been somewhat eclipsed as the jihadist threat has escalated in recent years. Algeria’s army is the most powerful in Africa after Egypt’s, yet the country has long had a commitment to the principle of non-intervention. This stance is formally enshrined in Algeria’s constitution, which states that “Algeria does not resort to war in order to undermine the legitimate sovereignty and the freedom of other peoples.” As a result, Algeria has pursued an approach in the Sahel based on coordinating the responses of regional states to security threats. In 2010 Algeria established a regional security organisation, the Comité d’État-Major Opérationnel Conjoint (CEMOC), which brings together Algeria, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger to cooperate and share intelligence in the fight against armed groups. Yet CEMOC and the associated Fusion and Liaison Unit have largely proved ineffective. Algeria’s commitment to non-intervention led it to resist sending troops to push back armed groups in Mali in 2013, when domestic forces were unable to manage the threat, though Algeria did allow French forces to use its airspace.

Even within the AU, Algeria may have lost some of its dominant influence over the security portfolio. The current Algerian PSC commissioner, Smaïl Chergui, was only narrowly re-elected to a four-year term in 2017, and some observers believe that Algeria may no longer hold the position after next year’s vote. Algeria was also unable to prevent its rival Morocco from gaining a seat on the PSC in 2018.

Algeria has also deployed a largely security-focused response to the increase in migration into the country over the last few years that seems to pay little heed to sub-Saharan sensibilities. Migration into Algeria rose after 2015 as the civil war in Libya diverted migrants who might previously have sought work in Libya or used it as a staging post to try to reach Europe. The increasing visibility of sub-Saharan immigrants in Algerian cities provoked some hostile reaction, including a public campaign in 2017 under the slogan “No to Africans in Algeria”.

While the government pushed back against this campaign, and promised to start work on a plan for regularisation, it has also forcibly deported large numbers of irregular migrants to Niger and Mali, including some from other African countries. Many have reportedly been abandoned in Algeria’s southern desert and left to make their way across the border on foot. In a protest against their treatment, a group of Malians who had been deported from Algeria attacked the Algerian embassy in Bamako in 2018. In the words of one Algerian specialist, the Algerian authorities never treat the reception of migrants as a diplomatic or geopolitical opportunity to improve relations with sub-Saharan African countries.

Against this backdrop, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, who was elected president in December 2019, has said he wants to lead a policy of re-engagement with Africa. Tebboune became president through a process that was rejected by Algeria’s large protest movement, and he is seen by domestic critics of the Algerian regime as a compromised leader. Nevertheless, he has set out an ambitious programme to rebuild Algeria’s continental profile. Tebboune attended the AU summit in February this year and used his speech to announce Algeria’s return to Africa, both in the context of the AU and in bilateral relations. In particular, the president announced that Algeria would set up an international cooperation agency focused on Africa and the Sahel (and evidently modelled on Morocco’s AMCI). Late in 2019, Algeria also ratified the agreement for the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). In June 2020, it completed construction of a key part of a projected trans-Saharan highway that is designed to connect Algiers and Lagos, with links to Chad, Mali, Niger, and Tunisia.

Finally, in May, Tebboune unveiled proposed amendments to Algeria’s constitution that would allow the country to send military forces overseas to take part in multilateral peacekeeping or peace-enforcement operations, and to restore peace in countries at the invitation of the host government. The change is evidently designed to help restore Algeria’s role as the leading power in providing security in its neighbourhood.

It will be some time before the success of these moves can be assessed. Some commentators have suggested that the new international cooperation agency is an outdated method of trying to gain influence, harking back to a time when sub-Saharan Africa was seen as a collection of poor countries needing help, and when Algeria had the wealth to undertake large and expensive projects. One observer of Tebboune’s speech to the AU commented that it did not seem to resonate with its audience.[3] Rather than dangling large projects that it cannot afford, Algeria might be better advised to make it easier for its firms to trade and invest in Africa by improving transport links, particularly flight connections, and loosening regulations governing foreign investment.

Meanwhile, in the field of security, the impact of any revision to Algeria’s doctrine of non-intervention will depend on the country also changing its strategic culture. That culture has tended to adopt a rigid approach and rejected support for any missions that are not conducted on Algeria’s terms. There have been signs recently of a shift in this direction, including renewed talks on regional issues between Algeria and France, and Algeria’s recent announcement of the provision of military aid to Mali, including the offer of 53 military vehicles. Such a shift would complement the role that Algeria has continued to play in promoting and supporting negotiations between the government and armed groups in Mali.

Tunisia: Untapped economic potential

Tunisia is unique among North African countries in that its growing interest in sub-Saharan Africa has no obvious geopolitical motive. Tunisia is not seeking to deepen its engagement with the rest of the continent because of any strategic rivalry or security concerns, but essentially for economic reasons. The outgoing prime minister, Youssef Chahed, hosted a US-Tunisian event to promote investment in Africa in February this year, and said that Tunisia wanted to launch a privileged partnership with African countries. The new prime minister, Elyes Fakhfakh, who took office soon after, has promised a strategic investment plan for Tunisia’s future that is also based on opening new markets in Africa.

Tunisia starts from a low base in trying to expand its reach into sub-Saharan Africa. President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who ruled the country for 23 years before the 2011 revolution, tried to orientate Tunisia towards Europe rather than Africa. While the first post-revolutionary president, Moncef Marzouki, visited several African countries, Tunisia’s governments since 2011 were more focused on addressing socioeconomic problems through subsidies and public employment than on seeking new markets overseas. In 2018, only 3.1 per cent of Tunisia’s exports went to sub-Saharan Africa, representing little increase from a share of 2.8 per cent ten years earlier. Tunisia suffers from a shortage of diplomatic and infrastructure links with the continent. Beyond the North African coastal countries, it has only 12 embassies to cover 49 African countries. The national airline, Tunisair, only serves eight sub-Saharan destinations, all in West Africa.

Tunisia took a step towards greater trade integration with sub-Saharan Africa when it joined the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) in 2018. However, Tunisia only began trading under COMESA rules in January 2020 and its exports to COMESA countries remain for the moment overwhelmingly focused on North African neighbours Libya and Egypt. In the meantime, Tunisia also received observer status with ECOWAS in 2017 (its position in the centre of North Africa makes it eligible for both eastern and western regional economic organisations). However, after Tunisia signed up to the AfCFTA, the Tunisian parliament failed to ratify the agreement when it was put to a vote in March 2020. The agreement can be resubmitted to parliament after an interval of three months, but the rejection seems to show that Tunisia’s political class has not yet embraced the idea of engagement with Africa.

The head of the Tunisia-Africa Business Council, Anis Jaziri, says that Tunisia’s commercial potential on the continent is held back by burdensome foreign exchange regulations and the weak international links of the country’s banks, as well as the shortage of transport connections. At the moment, Tunisian exports to Africa are mainly in industrial goods, including building materials, cables, and medical equipment. Some Tunisian firms, like the construction company Soroubat, have made successful investments in West Africa. But Jaziri argues that Tunisia has enormous potential in other higher-value areas of goods and services, ranging from higher education and medical services to information technology. Tunisia’s success in handling covid-19 may increase the appeal of its health sector to the continent. With better transport links, Tunisia also has potential as a base for European and other international companies that are looking for local African partners in sectors like health or IT.

Migration is also a factor in Tunisia’s relations with sub-Saharan Africa. According to official figures, there are around 7,500 sub-Saharan Africans living in Tunisia, but, when undocumented immigrants are included, many people believe the true figure could be around 20,000. The majority of these are from West Africa – particularly Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Senegal, Cameroon, and Nigeria. Until recently, the number of sub-Saharan Africans trying to use Tunisia as a base to reach Europe was minimal. According to the researcher Matt Herbert, only 401 out of the 4,678 irregular migrants apprehended by Tunisian authorities in 2018 trying to leave for Europe were non-Tunisian citizens. The deterioration of conditions in Libya has led to an increase in the proportion of foreigners trying to use Tunisia as a transit country, but the number of migrants trying to reach Europe from Tunisia remains low.

Many African immigrants in Tunisia have complained that they face racism and discrimination. A detailed study released recently by the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights found that migrants consistently said they felt unwelcome in the country. There is no formal asylum system. Most migrants are only able to work in the informal economy and they have suffered badly from the impact of covid-19. According to the UNHCR, 53 per cent of refugees and migrants in Tunisia have lost their jobs because of coronavirus restrictions. Tunisia adopted a landmark law against racial discrimination in 2018, but activists complain that there is no political commitment to follow through on it. Tunisia’s failure to integrate African migrants more effectively seems to indicate a continuing sense of detachment from sub-Saharan Africa.

Egypt: Protecting national interests

From February 2019 to February 2020, Egyptian president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi served as chair of the AU. This was the first time Egypt had been chosen for the position (which rotates annually between different African regions) since the body’s creation in 2002. Sisi’s selection underlined the increasing attention that Egypt has given to Africa and the AU in the last six years. Under the presidencies of Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak, Egypt’s foreign policy was focused on the Middle East, and its relations with the US and Europe overshadowed its engagement with its own continent. After Sisi seized power in 2013, overthrowing the popularly elected president Mohammed Morsi, the AU went so far as to suspend Egypt’s membership for a year. But since then, Sisi and Egypt have made a concerted effort to repair their ties to Africa.

The shift reflects the changing nature of the security risks that Egypt faces. Since 2011, the spread of jihadist groups across North Africa and the Sahel, and the civil war in Libya, have led Sisi to see potential threats across Egypt’s African borders. At the same time, Sisi’s campaign against the Muslim Brotherhood at home has led him to identify all offshoots of the Brotherhood as allied to terrorism, and to orientate Egypt’s foreign policy towards preventing the spread of political Islam across the region. The overthrow of Sudan’s long-time president, Omar al-Bashir, after massive popular demonstrations also raised the spectre of instability in a neighbouring country. Most significantly, Ethiopia’s decision in 2011 to begin building the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile close to its border with Sudan threatened Egypt with the disruption of the water supply on which it overwhelmingly depends. Ninety per cent of Egypt’s fresh water comes from the Nile, and the river has been central to Egyptian life and identity for thousands of years. Sisi told the United Nations in 2019 that the water of the Nile was “a matter of life and an issue of existence for Egypt”.

Egypt’s size and wealth guarantee that it has influence in Africa when it chooses to engage. It has the third-largest economy on the continent after Nigeria and South Africa, and its 2019 growth rate of 5.6 per cent was much the highest of the three. Egypt has an experienced and skilled diplomatic service and an extensive network of 40 embassies across sub-Saharan Africa. During its period as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council in 2016-17, it won friends in Africa by working to coordinate the activity of the African members of the UNSC and the PSC. Observers of the body say that Egypt has been careful to put high-quality officials into the AU, including the organisation’s legal counsel, Namira Negm.[4] Egypt is particularly active within the AU on security questions and won agreement to host the AU’s Centre for Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development in Cairo. According to news reports, Egyptian diplomats describe these efforts as part of an attempt to increase its influence within the organisation.

Nevertheless, during its period chairing the AU, Egypt did not focus the organisation on its own most pressing regional challenges, which it prefers to address in other ways. Egypt’s ambassador to the AU cites the coming into force of the AfCFTA, improving the efficiency of the AU, infrastructure development, and progress on the Centre for Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development as the signal achievements of its term. But, because it has taken positions that diverge from the majority view within the organisation, Egypt has not promoted AU involvement on the crisis in Libya, the transition in Sudan, and the Ethiopian dam. It sought the AU chair as part of a general campaign to build influence rather than as a way of directly pursuing its strategic goals.

On Libya, Egypt has strongly supported the renegade general Khalifa Haftar, which renders it unfit to lead any mediation effort, in the view of other AU member states. Egypt has also been at odds with the majority of AU countries over the transition in Sudan. In the belief that Sudan’s army provides the best foundation for national stability, Egypt has joined its Middle Eastern allies, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, in backing the Sudanese military in their continuing power struggle against civilian officials. Sisi met with the influential general Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (widely known as Hemeti) in Cairo last July and emphasised Egypt’s desire to support “the stability and security” of Sudan. But the AU has been more favourable to the pro-democratic civilian movement. Against Sisi’s opposition, the AU suspended Sudan for three months in June 2019 after a military attack on protesters. And the AU weighed in behind Egypt’s rival, Ethiopia, in its mediation efforts last summer, leading to a power-sharing deal and a transitional roadmap.

The Ethiopian dam remains Egypt’s most important regional priority. Work on the GERD is more than 70 per cent complete and Ethiopia says it will be ready to start filling the reservoir behind it this year. It has been estimated that if the reservoir were filled over seven years, Egypt would lose 22 per cent of its annual water budget. Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan signed a declaration of principles in 2015, but since then technical negotiations on the details of an agreement have stalled. The remaining points of disagreement between Egypt and Ethiopia concern the legal status of any agreement, mitigation measures in case of drought, and how to handle disputes. The World Bank and, more recently, the US have tried to mediate, but Ethiopia rejected a US-crafted deal earlier this year. Instead, Ethiopia has sought to involve the AU and its current chair, President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa, in a new round of mediation. In late June, the parties met under AU auspices and announced that they hoped to resolve the outstanding issues within two weeks. If the discussions are successful, this would represent an instance of Africa resolving its own disputes and help dispel Egyptian doubts about the AU’s fairness on this topic.

Like other North African countries, Egypt has also tried to increase its economic ties to sub-Saharan Africa in recent years. Egypt has been a member of COMESA since 1998 and was one of the first countries to ratify the tripartite free trade area linking COMESA with the East African Community and the Southern African Development Community that was agreed in 2015. Egyptian trade with fellow COMESA member states increased by 32 per cent between 2018 and 2019. Egypt has also undertaken a series of large cooperation projects with Nile basin countries in recent years, above all in irrigation and water management, and organised a series of investment forums in Cairo. Nevertheless, Egypt’s trade with sub-Saharan Africa remains comparatively low, accounting for only 5.7 per cent of its exports and 1.5 per cent of imports in 2018. The impression persists that Egypt treats its security interests in Africa as a priority, and sees economic links, at least in part, as a way to promote its strategic goals.

Conclusion and recommendations

North Africa’s “return to Africa” has been a striking feature of the region’s foreign policy in recent years. All four of the countries analysed in this policy brief have stepped up their engagement with sub-Saharan Africa, recognising it as both a leading emerging market and a region whose influence in international politics is likely to increase in the coming years. But this report has also shown how North African countries are pursuing distinctively national agendas in Africa and have met with a correspondingly mixed response from sub-Saharan African countries. North African countries have returned to Africa for their own reasons, and their initiatives have often left existing tensions with sub-Saharan countries unresolved.

Morocco and Egypt, in particular, have brought a strong sense of their strategic interests into their engagement with Africa. Many sub-Saharan countries have maintained their wariness of these positions even as they welcome the attention to African institutions and processes. North African countries have also continued to equivocate about their position in Africa. In what has been called a “double pursuit”, they are committed to maintaining their privileged relationships with the EU even as they deepen their ties to their own continent. North African countries have shown no interest in being associated with negotiations between the EU and the African, Caribbean, and Pacific group of states about a successor to the Cotonou Agreement, which expires at the end of this year. North African development cooperation with sub-Saharan Africa offers benefits to the continent but can also provoke resentment if it is cast in a tutelary form, with North African countries seeming to offer the benefit of their more advanced status.

The EU should take account of the complex nature of North African engagement with sub-Saharan Africa in its relations with the continent. Firstly, it will get better results from its cooperation with North African countries on migration if it understands the African context of its partners’ policies. As Tasnim Abderrahim has argued for ECFR, the EU and its member states should appreciate that migration is a sensitive issue for North African countries as well as European ones. European and sub-Saharan African interests can be in tension, and any impression that North African countries are acting as Europe’s enforcers or gendarmes will complicate their relations with source countries. Cooperation on border management, and supporting the integration of migrant communities, is likely to be more effective than pushing North African countries to accept migrants intercepted at sea.

In the field of security, the EU and its member states should welcome signs that Algeria is re-engaging in the Sahel and encourage it to build links with the G5 Sahel and to contribute actively to stabilisation and development. The EU should also be prepared to step up its involvement in efforts to resolve the Nile dam dispute if the current round of talks falters. Europe may be better able to present itself as a neutral power than the US, which is seen as close to Egypt.

As the EU looks to deepen its relationship with Africa, it should naturally seek to coordinate where possible with North African continental initiatives. Commercial ties between Maghreb countries and the Sahel could help European objectives of promoting stability. Supporting African economic integration is one of the goals mentioned in the guidelines for a new EU-Africa strategy. This could be promoted by helping to create better infrastructure links between north African countries and the rest of the continent.

There is also scope for Europe to pursue triangular cooperation with North African countries in sub-Saharan Africa, joining together on projects in areas where North Africa has relevant experience to share. Morocco, in particular, has sought to promote this idea, which was endorsed in a joint EU-Morocco declaration in June 2019. Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia have international cooperation agencies that have carried out many projects in third countries in association with international institutions and developed countries, and Algeria has announced the creation of an international cooperation agency. In several areas, including

public health, rural electrification, renewable energy, and digitalisation, North African countries are pursuing similar development cooperation goals as Europe and have relevant experience, and it would make sense for efforts to be coordinated.

At the same time, the EU should remain cautious about aligning itself too strongly with North African strategies in Africa. Triangular cooperation is only valuable to the extent that all parties genuinely share objectives and the arrangement offers added value. As the EU tries to move towards a more reciprocal partnership approach with Africa, it should remember that many sub-Saharan countries look at the posture of North African states with some distrust. Where North African countries are thought to approach the rest of the continent with a sense of their own more advanced status, it may not help Europe to ally with them. Above all, European policymakers should be aware of the interests, tensions, and rivalries that underlie North African policies on the continent. Sub-Saharan Africa’s stance towards North Africa is increasingly pragmatic. A correspondingly pragmatic approach – that looks for convergence where possible but remains alive to the national agendas of powerful North African countries – would provide the best foundation for Europe’s own relationship with Africa.

About the author

Anthony Dworkin is a senior policy fellow at ECFR. He works on North Africa and also on a range of subjects connected to human rights, democracy, and the international order. He is also a visiting lecturer at the Paris School of International Affairs at Sciences Po and was formerly executive director of the Crimes of War Project.

Acknowledgements

This paper draws in part on research conducted during an ECFR council members’ research trip to Morocco in March 2020. In addition to the people cited in the text, I would like to thank Faten Aggad, Amandine Gnanguenon, and ECFR council members Nicola Clase, Teresa Gouveia, Fabienne Hara, and Ana Palacio for helpful discussions. Within ECFR, Julien Barnes-Dacey, Andrew Lebovich, Theodore Murphy, and René Wildangel provided valuable comments on earlier drafts of the paper. Thanks to Robert Philpot for editing and to Adam Harrison for designing the graphic.

This paper was made possible through the support of Compagnia di San Paolo and the support of the foreign ministries of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa programme.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.