Seven days to save the European Union

The European Parliament elections take place next week – our latest pan-European polling reveals voters are deeply concerned about what the future holds

See coverage in ![]() The Guardian,

The Guardian, ![]() La Stampa,

La Stampa, ![]() Süddeutsche Zeitung,

Süddeutsche Zeitung, ![]() Le Monde,

Le Monde, ![]() Gazeta Wyborcza

Gazeta Wyborcza

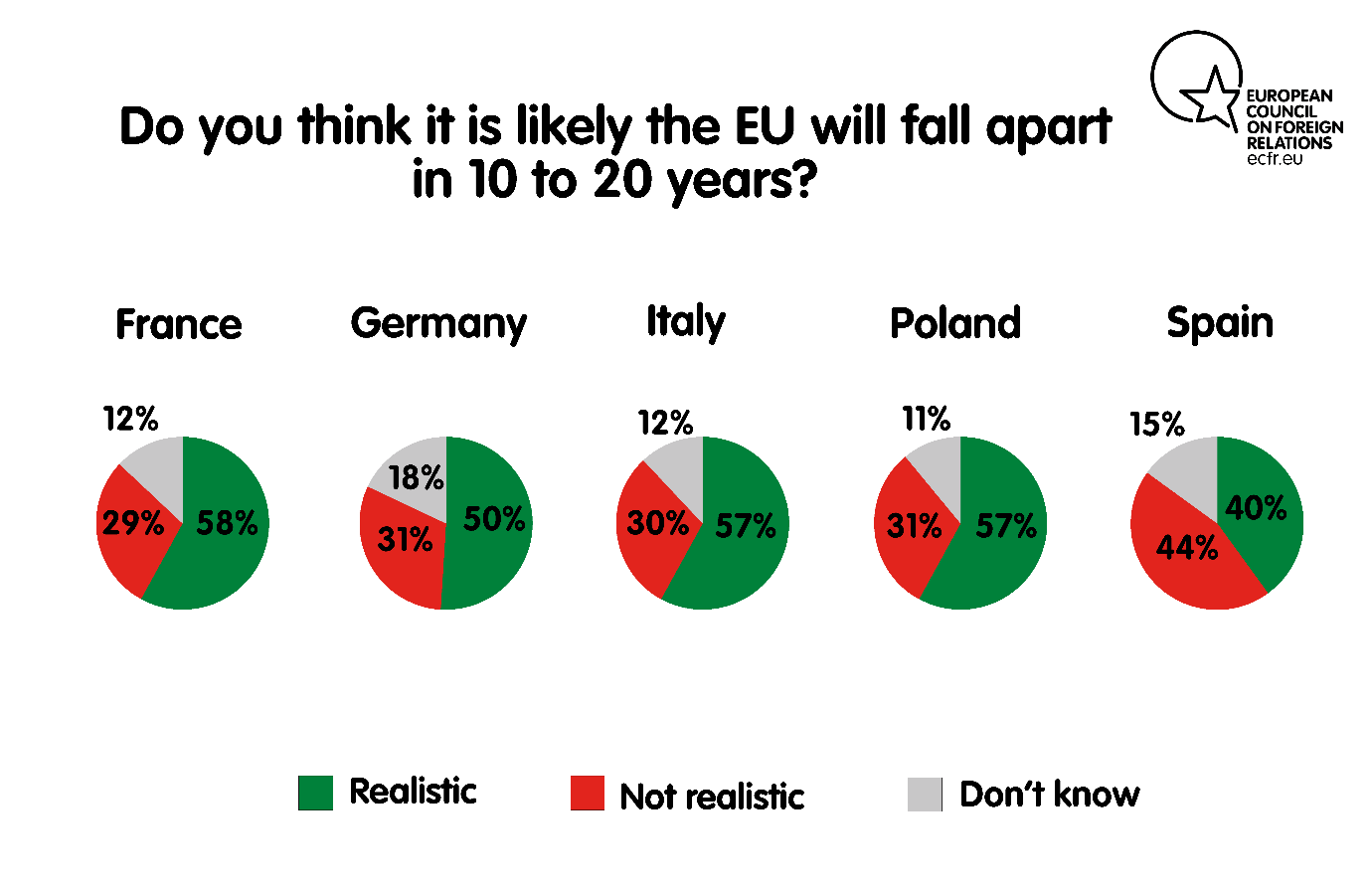

There are seven days to resolve the paradox at the heart of the European project. With the European Parliament election just around the corner, support for EU membership is at a record high – two-thirds of Europeans currently believe it is a good thing, the largest share since 1983 – and yet a majority also fear that the European Union might collapse. The challenge for pro-Europeans is to use this fear of loss to mobilise their silent majority, and to ensure that it is not just anti-system parties that get their say on 26 May.

The surge in support for EU membership is undoubtedly a reaction to an uncertain environment. We only come to appreciate the value of the European security net as we come close to losing it. Just look at the United Kingdom, where previously complacent pro-Europeans are only now coming together, almost three years after the Brexit referendum, to mobilise in favour of the EU.

The surge in support for EU membership is undoubtedly a reaction to an uncertain environment. We only come to appreciate the value of the European security net as we come close to losing it. Just look at the United Kingdom, where previously complacent pro-Europeans are only now coming together, almost three years after the Brexit referendum, to mobilise in favour of the EU.

Voters’ anxiety about the future manifests in a range of different areas. Firstly, this feeling of precariousness has a significant economic dimension. In almost all countries ECFR surveyed, a majority of people felt their children’s lives would be worse than their own. In every one of these countries, the capacity to afford the comforts of life was one of the top two factors respondents thought would ensure a good future for them and their families.

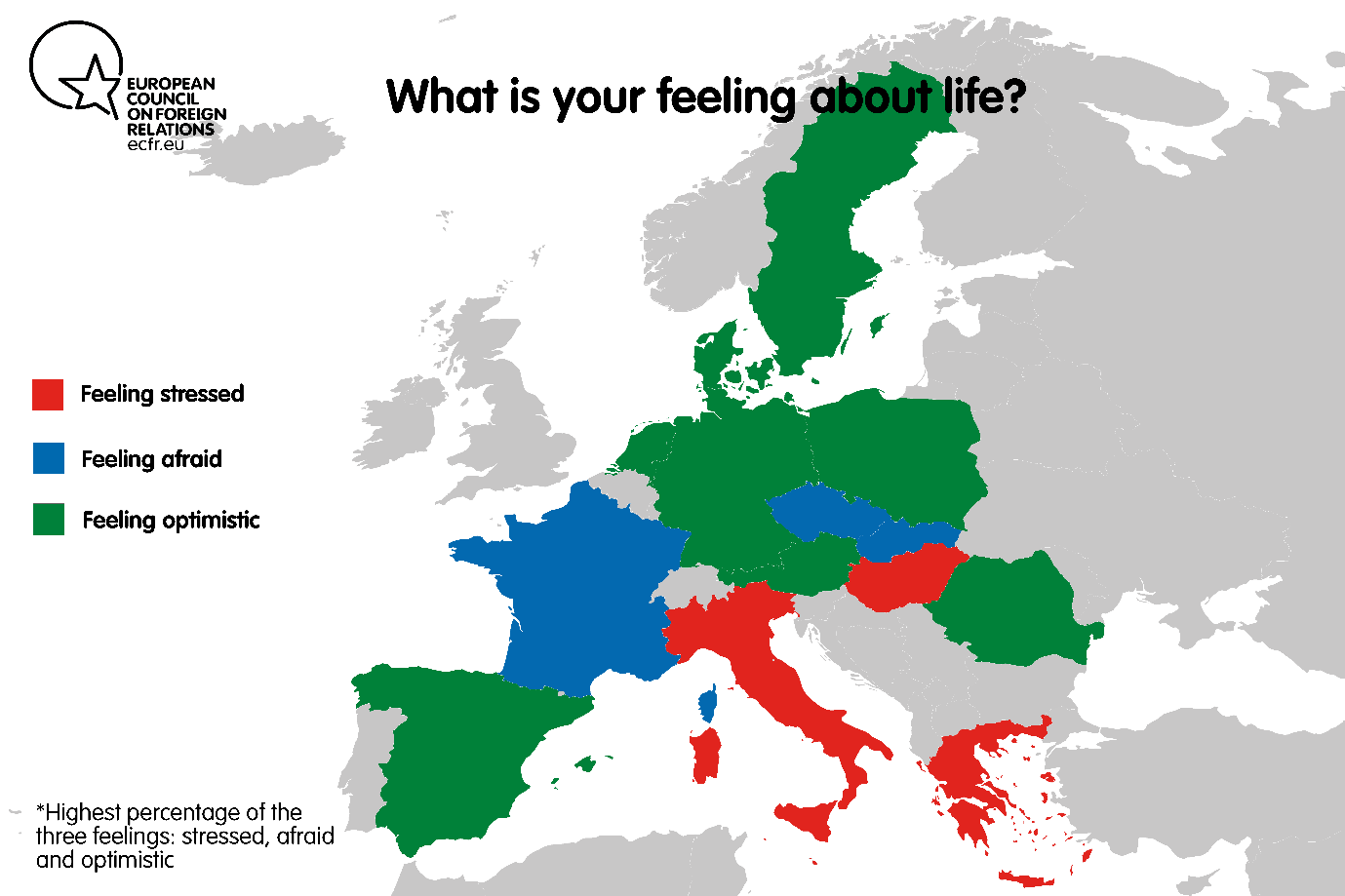

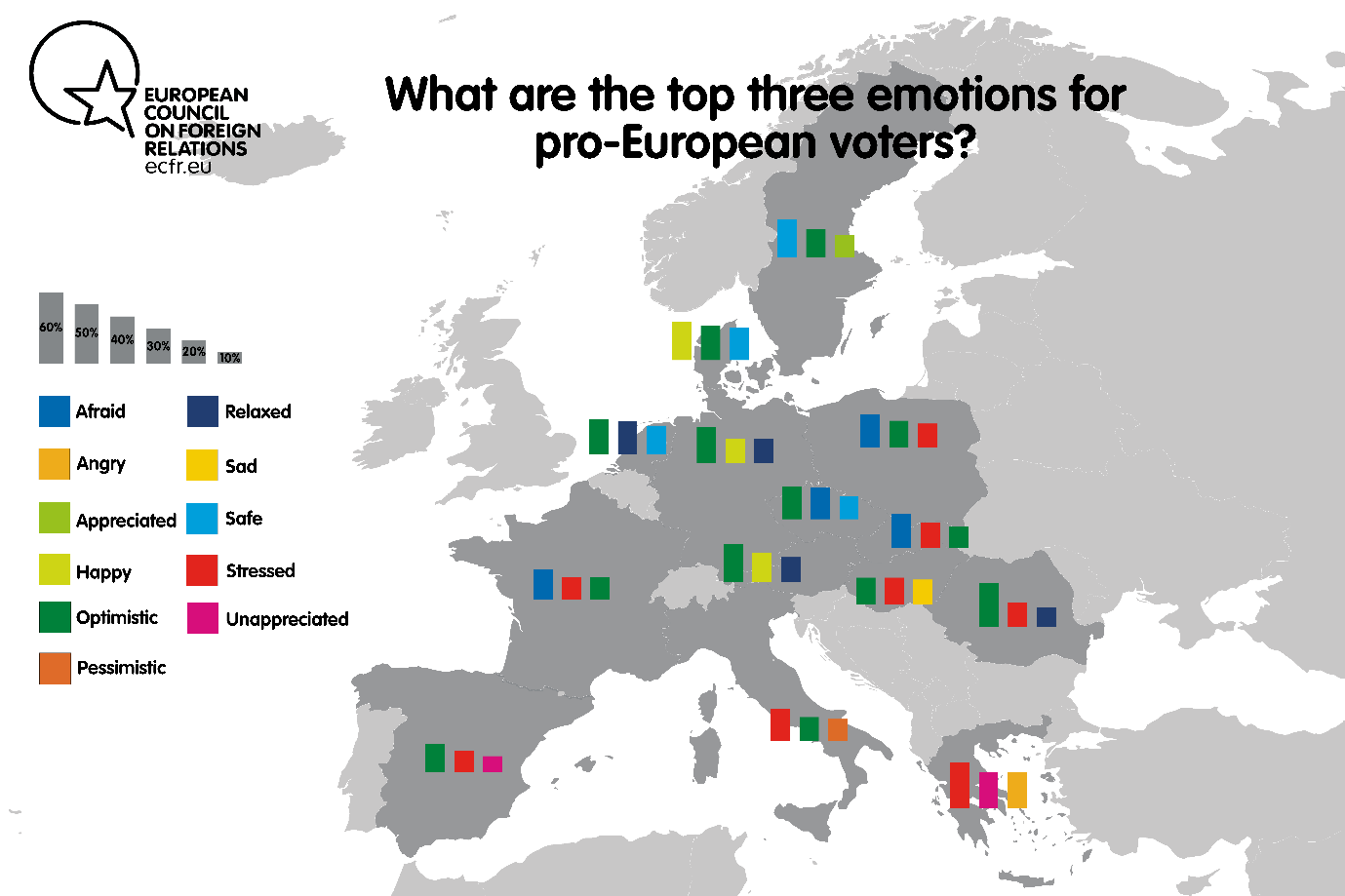

There is also a geopolitical dimension. Europeans are concerned about the volatile international environment, particularly the uncertainty in the EU’s relationships with the United States, China, and Russia. Safety was a very strong preoccupation of respondents when they were asked about their future. Europeans are now fearful (“afraid” was the top emotional identity of voters in France, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia) and “stressed” (particularly in Italy, Hungary, and Greece) but, nevertheless, they have a resilient “optimism” (as is especially clear in Germany, Poland, Spain, Austria, and Romania). Denmark and Sweden, where respondents’ top answers were “happy” and “safe” respectively, were outliers.

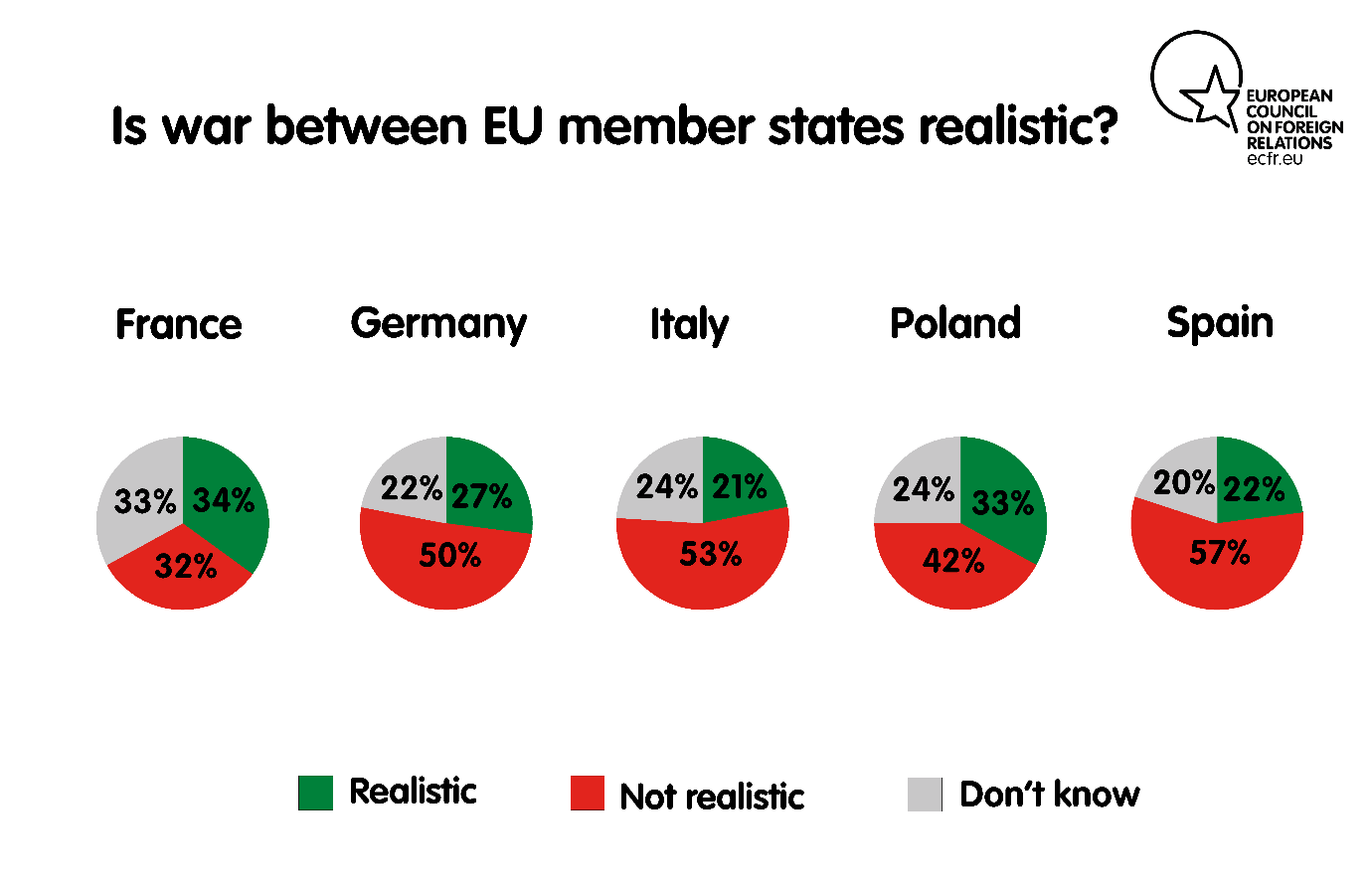

The EU is the world’s best-known peace project. But, now, many are worried that even this has run its course. ECFR’s survey revealed that three in ten voters believe that war between EU countries is possible. This sentiment came through in the prevalence of concern about nationalism as a threat to the EU: in Austria, Germany, and Greece – all countries with a high per capita intake of migrants since 2015 – it was perceived as at least as much of a threat as immigration.

For these people, the reality of contemporary Europe is one of competition and conflict rather than cooperation. It is not that they necessarily think that war will break out tomorrow, but that there is a logic of conflict in a deeply divided continent. Currently, this logic of conflict is driving many Europeans in two directions: towards disconnection with the political system (in five large member states, majorities of those planning to abstain from voting believed war between EU member states was possible) or towards anti-system parties (46 percent of Rassemblement National and 41 percent of Alternative for Germany supporters believed that such a war was possible).

The challenge consists in reconnecting with these voters, convincing them not only that voting is worthwhile – with the issues they care about for the future in mind – but also that mainstream parties can provide them with a safer, fairer, and more comfortable future. French President Emmanuel Macron is one of the few leaders from the centre of European politics who has tried to make this case for a reformed, more determined Europe that protects. But his reform project has met with a lukewarm response from his counterparts in other capitals, not least Berlin – who have proven unable to think beyond the confines of traditional party politics in this delicate moment.

Green parties across the EU have also tried to make the case for internationalism to their voters. But, although ECFR’s survey data shows latent and growing engagement with green issues, these parties have failed to create sufficient drama and urgency around their agenda to create a surge in their support.

For real inspiration on how to communicate beyond voters who are already mobilised, pro-Europeans need to look outside the party system. Think Extinction Rebellion or the gilets jaunes (yellow vests) – these movements use the logic of conflict to communicate a different vision of the future. In the focus groups ECFR organised in Germany, France, Italy, and Poland as part of its Unlock project, the excitement around images of the gilets jaunes or Extinction Rebellion was palpable. Yet the energy went straight out of the room when participants were confronted with images of the European Parliament. Extinction Rebellion uses direct action to open doors, but has set out a policy agenda in its manifesto and is willing to meet and engage with politicians – in an attempt to connect the political system to the anti-system world.

Pro-Europeans also need to focus on reconnecting with voters. They must show that they recognise the deep rift between voters and parties, and must offer a vision of a European future that makes the silent majority feel it is worth coming out to vote in late May.

It is not yet too late: with a volatile European electorate, there may be up to 97 million people planning to vote who could still be persuaded to support different parties, and more who could be mobilised to do so with powerful arguments. But with, one week to go until the election, it may soon be too late – at least for this current round in the conflict.

This latest analysis is part of our Unlocking Europe's majority project. For more polling and analysis as part of this project, click here.

Methodology

The second round of polls was conducted by YouGov in March 2019, with 1,000 samples for each of 14 countries, except Sweden where it was 2,000, and Denmark 1,400, and Greece and Slovakia 500.

The full list of 14 countries includes: Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, and Sweden.

See coverage in:

The Guardian: “Majority of Europeans 'expect end of EU within 20 years'”

The Guardian: “Majority of Europeans 'expect end of EU within 20 years'” La Stampa: “Italia e Francia dominate dalla paura: “In dieci anni l’Unione può dissolversi””

La Stampa: “Italia e Francia dominate dalla paura: “In dieci anni l’Unione può dissolversi”” Süddeutsche Zeitung: “Einfach machen”

Süddeutsche Zeitung: “Einfach machen” Le Monde: “Deux électeurs sur trois redoutent le démantèlement de l’Union européenne”

Le Monde: “Deux électeurs sur trois redoutent le démantèlement de l’Union européenne” Gazeta Wyborcza: “Badani w 14 krajach UE: Unia chyli się ku upadkowi, a pomiędzy krajami Wspólnoty wybuchnie wojna”

Gazeta Wyborcza: “Badani w 14 krajach UE: Unia chyli się ku upadkowi, a pomiędzy krajami Wspólnoty wybuchnie wojna”

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.