2020: The year of economic coercion under Trump

European countries and businesses are unlikely to escape the impact of US extraterritorial measures on China, Russia, and Turkey.

The United States has long been able to use its dominant position in the global economy to impose extraterritorial measures as a tool of economic coercion in pursuit of its foreign policy objectives. Under the Trump administration, such measures have created significantly more problems for Europe than they once did, and the president’s use of economic tools has proved highly influential with both governments and commercial actors.

In 2020 economic coercion will likely continue to be the administration’s weapon of first resort in forcing other countries to support US policy priorities. US President Donald Trump appears to regard economic weapons as a much more attractive option than conventional military tools – especially in an election year. The US administration now uses geo-economic pressure directed against Europeans quite regularly, targeting (or threatening targeting of) European products like cars, wines, or energy projects to get Europe in line on policy issues like 5G network construction or the French digital tax. But there is also significant risk in cases where Washington has no intention of directly harming Europe, as many US coercive measures towards other countries will have a secondary impact on the continent. For Europeans, the greatest risks in this relate to countries whose economic ties to Europe are much stronger than those to the US – especially Turkey and Russia – because Washington can employ extraterritorial measures without imposing major costs on the US economy.

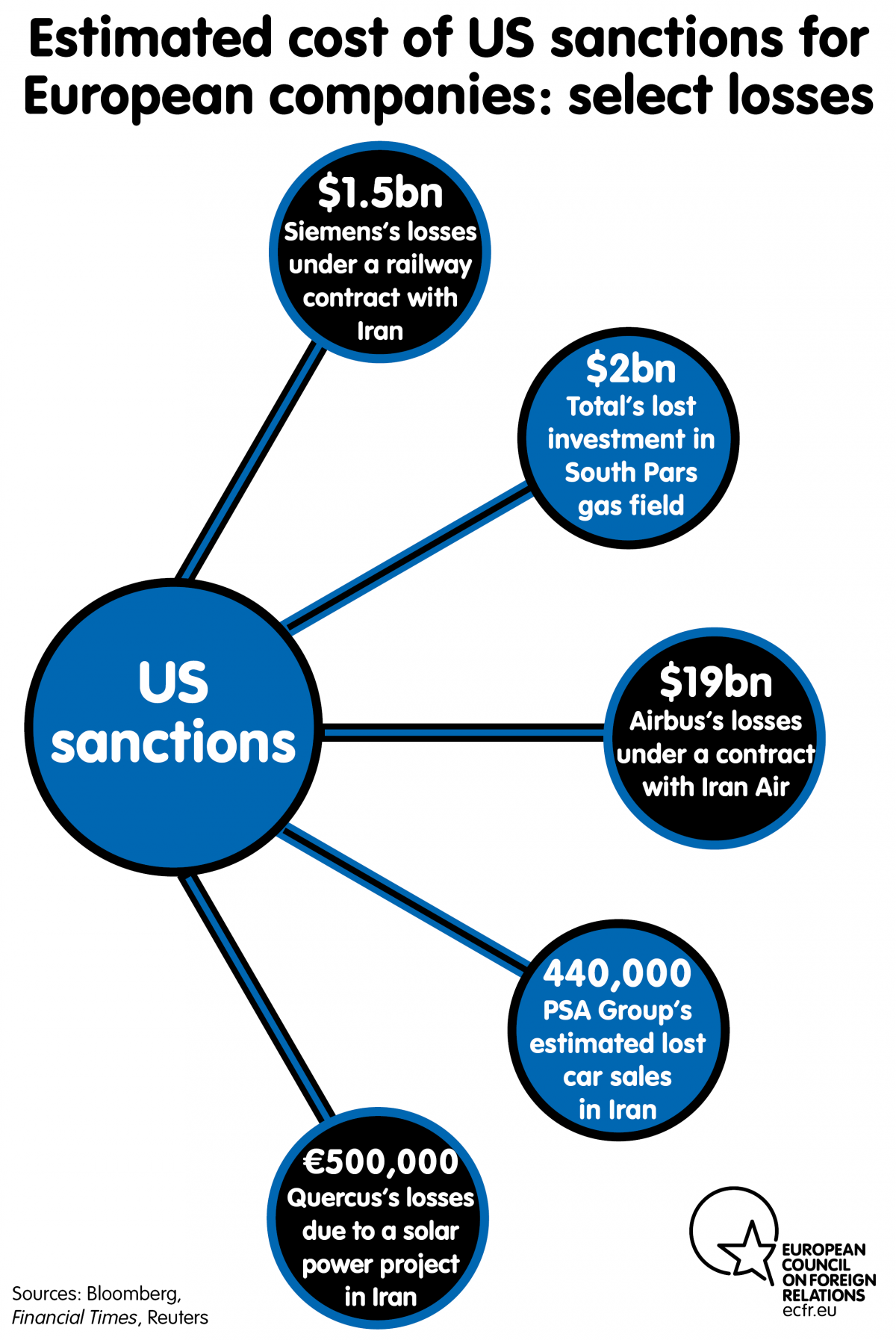

Three events in 2019 may have been a sign of things to come. Secondary US sanctions in the case of Iran show that, against Europeans’ declared political will to protect European companies from the impact of US measures, Washington can cut off Europe’s trade with a third country almost comprehensively if it chooses to do so.

The second warning shot demonstrated the way in which potentially devastating US sanctions against European companies could arrive overnight, in a way that was totally unforeseen even among experts. In October, Trump threatened to destroy Turkey’s economy in the context of its invasion of northern Syria. He also gave the US Treasury broad authority to sanction foreigners who operate in many sectors of that economy, and imposed sanctions on Turkish ministers. It was only because President Recep Tayyip Erdogan changed course that the Trump administration ultimately never implemented these secondary measures.

Trump appears to regard economic weapons as a much more attractive option than conventional military tools

In the third instance, the US sanctioned companies involved in building the Nord Stream 2 energy pipeline under the National Defense Authorization Act 2020. While the pipeline project itself is controversial, the case illustrates how European trade with third countries is under threat from not just an unpredictable president but also the US Congress, in which members of both parties had no scruples about interfering with Europe’s economy when American and European interests diverged. The US administration also reportedly used private threats to impose tariffs against Germany’s car industries to prevent the country from exploring ways to circumvent sanctions and complete the pipeline.

What Europe can expect

It is true that the Trump administration is trying to avoid tough measures on Russia, and that many in Washington are, for historical reasons, aware of how US policy on Russia might affect Europe. However, Europeans may be wrong to assume that, for this reason, there will be no more extraterritorial measures that affect their trade with Russia in 2020. Due to the tension between the administration and Congress, US foreign policy will remain unpredictable throughout this election year.

At the very least, it should come as no surprise if Congress toughened its measures targeting Russia in 2020, despite the economic stakes for Europeans. Both parties in Congress could potentially prepare a more comprehensive package of such measures going beyond the measures in the National Defense Authorization Act 2020, which includes the Nord Stream 2 sanctions, and the US sanctions legislation on Russia that is already in place. The Defending Elections from Threats by Establishing Redlines (DETER) bill that was introduced to Congress in 2019, but has not secured the support of a sufficient number of senators, gives an impression of what might be coming Europe’s way in this case: it would freeze assets of foreign persons that invest in Russia’s energy sector and therefore force European banks to retreat from either Russian or US markets. The US administration, too, could choose to take a tough approach in limited areas to demonstrate to the public that it is not cosying up to Russian President Vladimir Putin during the election campaign.

Hawkish lawmakers like Marco Rubio have been calling for drastic measures to prevent China “exploiting American capital markets”

Meanwhile, the interaction between Trump and Congress on Turkey will be a source of great uncertainty in 2020, following Turkey’s military incursion into north-eastern Syria in October 2019 and its purchase of Russian-made S-400 air-defence systems last year. So far, Trump has made use of his presidential waiver to avoid imposing the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), and other sanctions legislation, on Turkey. But Congress could force him to sanction Turkey. Key senators like Lindsey Graham say they would require Trump to fully implement CAATSA if Turkey activates the S-400 systems. If Trump can convince Erdogan not to activate them, Congress would be unlikely to follow through on its threats. But Russia has great influence over Turkey, not least because it can threaten to massively increase refugee flows from Syria. Moreover, Erdogan has his own domestic considerations regarding the S-400 systems and may not be able to afford to halt their activation for too long. If Congress imposes such sanctions, they will be targeted, probably punishing specific Turkish entities with close ties to Erdogan’s inner circle and possibly parts of the Turkish defence and energy sectors. European business in these areas could get hit along the way.

So long as Europe and the US are at odds over Iran policy, Washington will seek to undermine European efforts to sustain the nuclear agreement with Iran by exerting economic pressure. In January 2020, news broke that shortly before the decision by European governments to activate the dispute resolution mechanism under the nuclear deal, the Trump administration had threatened them with auto tariffs. While it seems that the European governments had made their decision long before it was implemented, the news was a complete PR disaster for Europe in terms of asserting its own sovereignty over foreign policy.

Moreover, American officials repeatedly warn that the US will not hesitate to directly sanction any entity that does business with Iran. Indeed, several Chinese companies have already been targeted by such measures. Interestingly, it seems that as part of the first phase in the China-US trade deal, some sanctions have been eased against Chinese companies involved in trade with Iran. As a consequence, China may roll back its oil exports from Iran, at least while trade talks are progressing positively.

Europe and the US may face another showdown over Iran if the White House sanctions elements of Europe’s new Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) with Iran. Europeans’ restriction of INSTEX’s initial scope may not be enough to avoid clashes with the Trump administration, especially if the US begins to assert that the recently initiated humanitarian channel for trade with Iran (via the Swiss government) has neutered the core purpose of INSTEX. In addition, the US may seek to narrow the scope of permissible trade with Iran through targeting imports into Iran and other sectors of the Iranian economy.

Over the summer of 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron proposed the extension of a $15 billion credit line to Iran in return for Tehran’s full compliance with the nuclear deal. However, French officials emphasised that the US administration would have to approve such an initiative for it to go through. The green light from the US is a requirement because most banks now require comfort letters from the US Treasury to facilitate transactions with Iran. This is particularly the case now given the sharp peak in military escalation between Washington and Tehran in January 2020 that has resulted in even more US sanctions targeting Iran.

For Europe, perhaps the most critical aspect of US extraterritorial measures in 2020 will relate to China. It is difficult to assess how Sino-American relations will evolve in the next year. While Trump has struck a deal on the first phase of trade negotiations with Chinese President Xi Jinping, not least to demonstrate his deal-making credentials in the run-up to the US presidential election, there is unlikely to be a more comprehensive agreement on phase two of the talks in 2020. The US could continue to hit China with a combination of formal tariffs, commerce entity listings of tech companies, and sanctions targeting specific entities; and it could expand such measures.

There is a risk that this will put Europeans in an increasingly difficult position, as companies in some sectors could face the dilemma of having to choose between the US and China. One of the more extreme options open to the US is to shift the trade conflict with China to financial markets in 2020 – by, for instance, hindering capital flows to China. There are signs that Washington is considering such measures to limit US (and potentially European) investments in certain sectors of the Chinese economy. Hawkish lawmakers in Congress like Marco Rubio have been calling for such drastic measures to prevent China from “exploiting American capital markets” and the Trump administration claims a crackdown on investment flows to China is an option it is actively studying.

Meanwhile, the US Export Control Reform Act, which the US government is starting to implement in 2020, has extraterritorial implications for European tech companies. Under the act, the US government will place export controls on “emerging” and “foundational” technologies such as artificial intelligence, semiconductors, and biotechnology. The act only applies to US exports, but it will affect global value chains. It will have an indirect impact on European firms that supply components for US products.

Critically, some companies might be unable to maintain their current export practices with places unrelated to the US unless Washington grants them special licences. This will be the case when Europe re-exports tech products with at least 25 percent US content. (In special cases, such as semiconductors, any amount of US content will have a licensing requirement.) The US Department of Commerce had issued an advance notice that worried many Europeans because it seemed Washington would apply wide definitions of what constitutes “emerging” and “foundational” technology and thus potentially impact on European tech trade to a great degree. But the first concrete application of the new export control law in early 2020 has focused narrowly on specific kinds of new artificial intelligence technology in a clearly defined area. Still, the US will increasingly restrict new technology trade in many areas and Europeans will need to pay close attention to make sure they can trade according to their own, rather than American, rules.

Not all these potential measures run counter to European interests. For instance, those targeting technology transfers to China could benefit Europe strategically. But, given that American politics rarely takes Europe’s interests into account these days, European governments need to seriously begin developing a long-term plan for defending European interests against US extraterritorial measures. In the meantime, unless and until Europe builds this resilience towards economic coercion deployed by Washington, it will continue being forced to follow US policies.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.