No going back: Why decentralisation is the future for Syria

Summary

Syria now suffers from deep divisions along both ethno-sectarian and geographic lines.

While economic links and interdependency persist between the various parts of the country, and most Syrians remain remarkably attached to the idea of national unity, the country is fragmenting into competing centres of power. This fragmentation extends to government-held areas where local power brokers are also asserting independence, challenging Damascus’s ability to hold on to power.

Interview with the author

To load the audio player provided by Soundcloud, click the button below. This means Soundcloud will receive technical data about your device or browser, as well as information about your visit on this page. Soundcloud may use cookies and may transfer your data to servers outside the EU, where the level of data protection may not be equivalent to that in the EU. For more information visit our privacy policy.

Political and economic decentralisation, including a special status for Kurdish areas, is fast becoming a necessary condition for solving the conflict. For this to become a reality, there needs to be a formal devolution process, fairer allocation of resources – particularly oil revenues -, and efforts to reduce disparities in economic development.

European actors should recognise the reality on the ground and shift their focus away from achieving a centralised power-sharing agreement and towards negotiations based on a devolved politics. A decentralised model will be difficult to implement, but ironically may offer one of the few means of holding the country together.

Policy recommendations

- Syria should adopt a decentralised political system based on the transfer of power away from Damascus and towards the governorate and district levels. Kurdish regions should get a special status with enhanced powers, as part of asymmetric decentralisation.

- While decentralisation is implemented and communities are recognised as political actors, the central state should retain a monopoly on a number of key sovereign attributes including defence, foreign affairs, and the printing of money.

- Syria’s official name should no longer contain the word “Arab”. This symbolic move would be in line with the overwhelming number of Arabic countries, including Iraq and Lebanon, and would send a positive signal to non-Arab Syrians.

- The state should teach all children from minority groups in their mother tongue. In Kurdish areas in the northeast, and Kurdish-majority districts of Damascus and Aleppo, schools should teach in Kurdish as well as Arabic.

- The state should ensure that it uses its available tools to limit geographic disparities in economic development. For instance, access to employment in each governorate should be based on its share of the country’s total population. Where possible, the same rule should apply to public investments.

- Oil export revenue should be reallocated, guaranteeing a proportion equal to each province’s population, on the principle that oil resources are equally owned by the entire country.

- Sectarian and ethnic communities should get some form of political representation at the central level. A bicameral system could be a solution. However, the Russian proposal to appoint government members on the basis of their religious or ethnic affiliation would go too far in terms of institutionalising these divisions, and would be a recipe for gridlock. Instead, community representation should be pushed at the legislative level, in an upper house tasked with monitoring and control and with preventing discrimination. At the executive level, there should be no appointments or allocation of official positions based on sectarian or ethnic affiliations.

Introduction

On 17 March 2016, while delegations from the Syrian regime and opposition were meeting in Geneva to discuss the prospects of a peace agreement, Kurdish groups met near the Iraqi border to announce the establishment of an autonomous federal region in northeast Syria.

The announcement was timed to signal to those attempting to decide the fate of the country that the conflict gripping Syria is not restricted to a binary struggle between the opposition and the regime, and that no long-term solution will be possible without the Kurds. Of no less significance was the location. Rather than meeting in Qamishli, the de-facto capital of the region now under its control, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) chose the small town of Rumeilan, which is the oil capital of northeast Syria.[1] To other Syrians, the Kurds were saying “this oil is ours” – and that there would be no end to the conflict without a new agreement on the allocation of the country’s resources.

This event marked a symbolic moment in Syria’s post-uprising history, highlighting the complex fault lines that divide Syrians and the issues over which the coming struggle for redistribution of power and resources will be fought.

More than five years after the beginning of the popular uprising, which has mushroomed into a war involving local, regional, and international players, deep divides have appeared among Syrians. These run along sectarian and ethnic lines as well as along the rural/urban divide. These divisions have created new geographical centres of power, backed by local military might and institutions that have gained independence from Damascus, to which they will not easily cede power again, as well as significant degrees of local legitimacy.

This paper sets out how these different regions are moving towards diverging systems of governance. Even today, some parts of the country continue to function better than many would expect. In areas controlled by the regime the pre-war order is largely in place, and the state still provides services and maintains law and order. Areas outside regime control have developed alternative institutions for education, security, and basic services – and some Kurdish areas have ceased to teach children Arabic altogether.

But, at the same time, most Syrians show a remarkable attachment to what still binds them together, including a shared history and a relatively well-functioning state, and overwhelmingly reject anything that could lead to a partition of their country. Economic links and interdependency persist between the various parts of the country, including across warring lines, as well as social ties.

In this context, this paper will argue that some form of political decentralisation, including a special status for areas of high Kurdish concentration, is a necessary condition for finding a solution to the current conflict, as well as beginning to rebuild the country. While not sufficient in itself, decentralisation offers one of the few means to include the competing local power centres that have emerged across the country during the course of the war; to better meet the wishes of Syria’s citizens, including the Kurds, for a fairer allocation of the country’s resources; and to reduce the risk of renewed conflict, while also ensuring that Syrians share a common future. The prospect of significantly enhanced local empowerment could also offer a critical political accompaniment to ongoing military efforts against the Islamic State (IS), which has exploited local grievances at the long-standing discriminatory and brutal hand of the central government to rally support.

In time, and once levels of violence subside, a decentralised Syria should take steps to reduce geographic disparities in economic development, dividing public investment and state jobs between governorates according to population, and allocating a fairer share of oil revenue to oil-producing regions. The district and governorate levels of government should be given far greater authority.

Moving Syria from the strong centralised state of the pre-uprising era to a decentralised model will be immensely challenging, but offers one of the few ways to chart a path out of the current conflict and hold the country together, albeit in a looser form. The alternative could well be complete breakup, despite the commitment of most Syrians to a unified Syria. As they look at the conflict, European governments should accept this, shifting their approach away from an unattainable central power-sharing agreement and towards negotiations based on the political and geographical division of power that is now the Syrian reality.

Of course, Syria is still in the midst of an all-out war. It has experienced more than five years of fighting, with enormous human and physical destruction, and the violence is likely to continue in the near future. Therefore, while the recommendations set out in this paper are not a short-term prospect, the changes that have already affected Syria should be taken into account in any settlement that might result from political negotiations.

A Kurdish fighter from the People's Protection Units (YPG) walks past a shop with Syrian national flags painted on its shutter in the southeast of Qamishli city, Syria, April 22, 2016. REUTERS/Rodi Said

A Kurdish fighter from the People's Protection Units (YPG) walks past a shop with Syrian national flags painted on its shutter in the southeast of Qamishli city, Syria, April 22, 2016. REUTERS/Rodi Said

Before the uprising

The main features of the decade that preceded the uprising include the arrival to power of Bashar al-Assad, the liberalisation of the economy and gradual sidelining of the state, which acted until then as an engine of wealth redistribution and as a social ladder for the country’s rural elites.

Until 2000, when Bashar succeeded his father, Syria’s central state was still relatively strong. State institutions delivered services across the country and the government remained the largest employer and investor. Much of the government apparatus was still made up of members of the rural elites, including the Alawite community, as well as those from traditional Ba’athist heartlands such as the Hauran region in the south, the Ghab region in the centre of the country, and the city of Deir ez-Zor.

Under Bashar, however, the state began to withdraw from its role. After 2005, in particular, subsidies for most goods and services were cut and public investment decreased. The government liberalised its trade and investment policies, gearing them towards the service sector – which was located in the urban centres and controlled by Assad cronies – at the expense of the suburbs, the countryside, and the more remote parts of the country, namely the northern countryside as well as the eastern and southern parts of Syria, which were the poorest and least developed parts of the country. The farming sector was hit by the surge in the cost of agricultural inputs imposed by subsidy cuts, as well as the government’s mismanaged response to several years of drought.

It is not insignificant that five years after the beginning of the uprising, the areas outside regime control largely correspond to those parts of the country that were economically and politically sidelined, while the relatively prosperous west of the country remains firmly under the regime’s grip.

The war fragments Syria

The economic losses from Syria’s conflict are estimated at over $200 billion, while data on falling school enrolment, rising poverty, and increasing divorce rates highlight the destruction of the country’s social fabric. Besides the huge human, economic, and social toll on Syria, one of the effects of the war likely to be lasting is the country’s division into distinct areas controlled and influenced by different, often competing, groups.

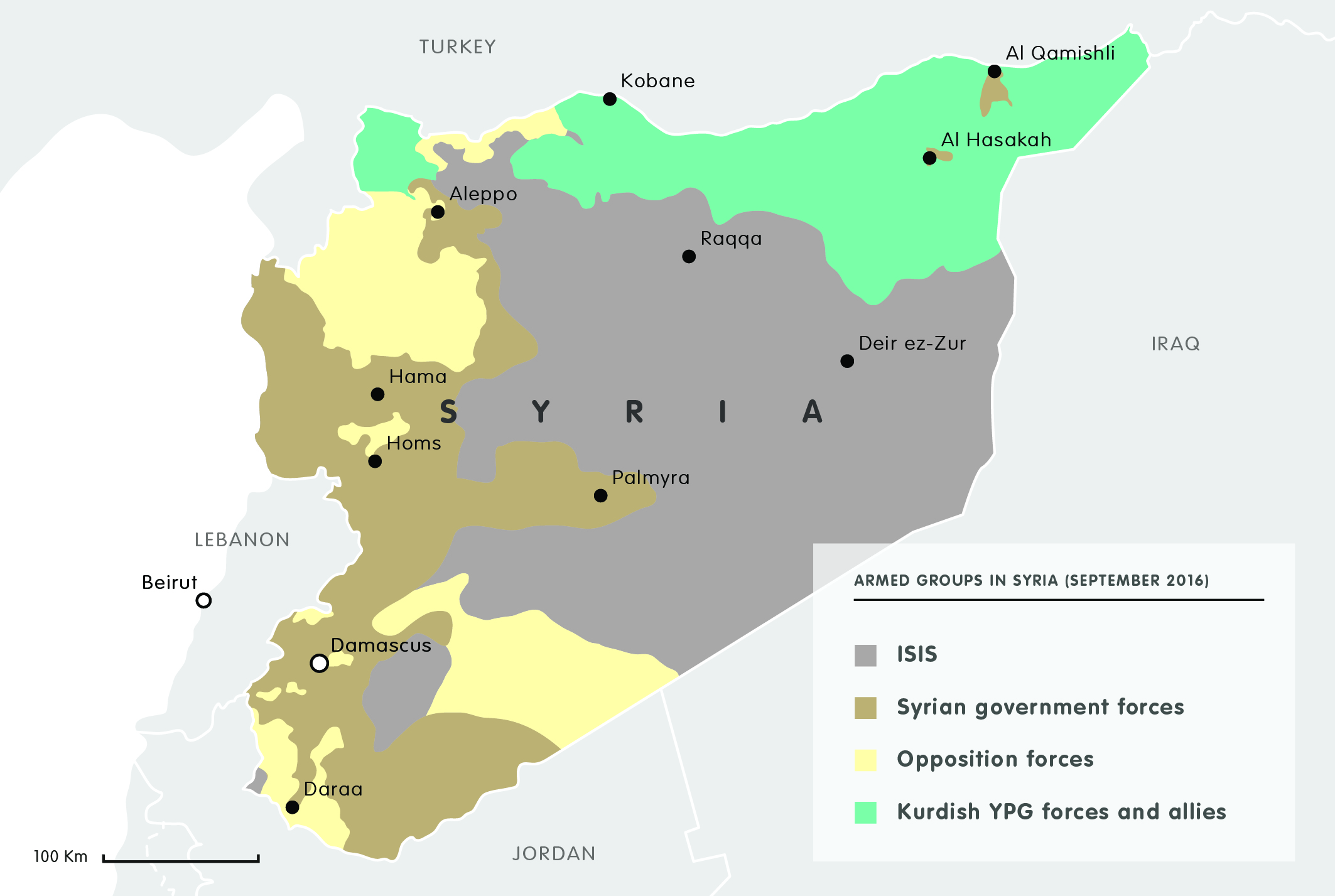

Syria is now divided into four main zones, one controlled by the regime, another by the Islamic State (ISIS), a third by the Kurdish PYD, and a fourth by various opposition groups including Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (formerly the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front). This latter area is itself not continuous, and is split between various small and large pockets of territory across the country. The frontlines, which have been broadly stable for at least two years, have raised barriers to trade, transport, and networking between the different parts of the country, without entirely breaking the links between them.

Broadly speaking, the areas outside regime control form a large crescent, running from the north-western province of Idlib along the Syrian-Turkish border, which is mostly under the control of the PYD, then the Syrian-Iraqi border, mostly ruled by ISIS. The zone ends south of Damascus, in the Daraa province, which is mainly in the hands of armed groups affiliated with the opposition.

In regime-controlled areas, the state is broadly unchanged from before the uprising. State institutions continue to function and maintain law and order, while the legal system remains unaltered. By contrast, areas outside of regime control have had to adapt to the almost complete withdrawal of the state. Local communities have created alternative systems to impose law and order, provide water and electricity as well as social services, to educate children, and to manage the economy. Opposition areas now have Sharia courts, while Kurdish areas have attempted to impose a cooperative system to run the economy.

In most opposition areas, children know of the Syrian state only through the barrel bombs falling from the sky, while in Kurdish areas the youngest are taught only Kurdish and do not speak Arabic, the country’s only official language. Residents of Douma, located just a few kilometres from Damascus, have not visited the capital for more than four years. In mid-2016, there were at least four different school curriculums taught to Syrian children, and three currencies circulating in relatively large amounts: the Syrian pound, the US dollar, and the Turkish lira – in July 2016, ISIS even reportedly started to mint its own coins.

In other words, not only Syria has fragmented politically, but also its various parts are spinning off in different directions, adopting opposing systems of governance that are becoming increasingly entrenched.

Regime areas

The regime-held areas include most of the western part of the country, and almost all of the main urban centres, with some two thirds of its population, and nearly all the Druze, Alawites, Ismailis, Circassians, and Christians still living in the country. These areas are not only geographically contiguous with each other, unlike those under the control of the opposition, but have more of a link with pre-2011 Syria. In these areas, the state still plays its role as a supplier of subsidised goods and services such as bread, education, health, electricity, and water, as the country’s main employer – civil servants are now estimated at more than 50 percent of the total working population, and a higher percentage of wage earners – and guarantor of law and order. The provision of state services, in contrast to the perceived chaos in other areas, especially those held by the opposition, is among the most powerful sources of regime legitimacy.

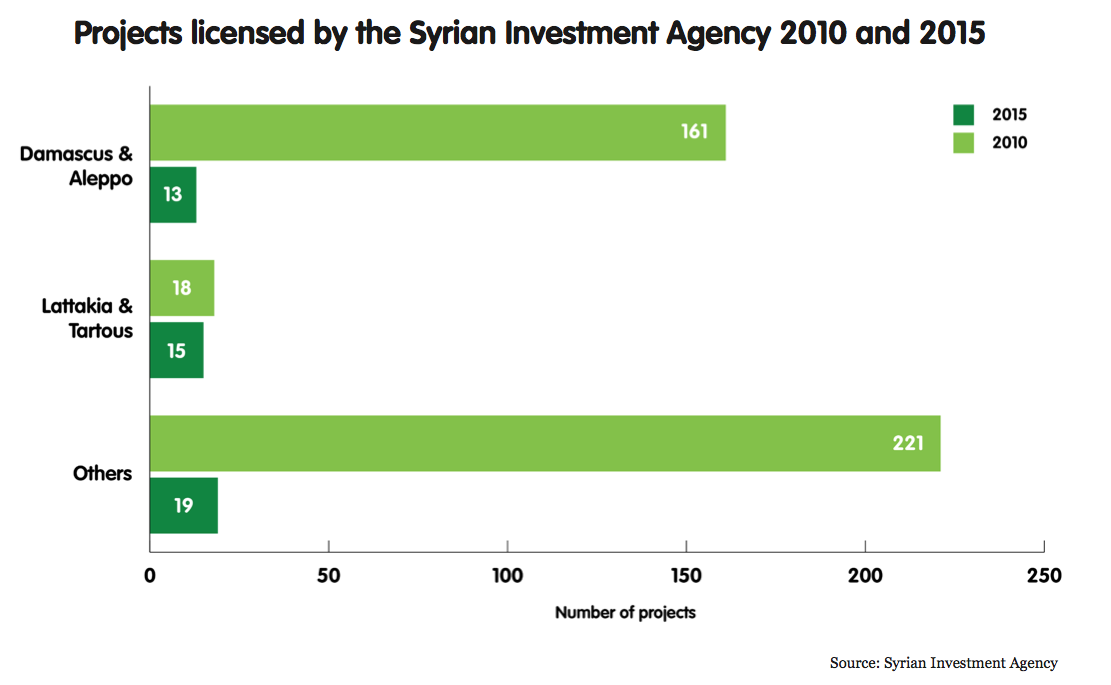

Amid the poverty and economic destruction, state employment and investment are used for social and political mobilisation; the coastal area, inhabited by Alawites who form the core of the regime support base, and military manpower, gets preferential treatment. In autumn 2015, for instance, the government’s announcement of 30 billion Syrian pounds (SYP) of investment in the Tartous and Lattakia provinces contrasted with a meagre 500 million for the city of Aleppo, despite the latter being much more affected by the war and in greater need of support.[2] Similarly, in April 2016, on Independence Day, SYP4 billion-worth of projects was promised to the Damascus countryside province, while SYP37 billion was promised to the two coastal provinces.[3]

Private investment, attracted by the relative security of the coastal region, has followed the same trend, though overall investment is only a fraction of what it was prior to the uprising. Data from the Syrian Investment Agency shows, for instance, that 32 percent of the private investments it licensed in 2015 were on the coast, while slightly less – 27 percent – were in the traditional economic powerhouses of Damascus and Aleppo. By contrast, in 2010, Damascus and Aleppo attracted 40 percent of the projects, while a meagre 4.5 percent went to Lattakia and Tartous.[4]

State employment is also a means of buying allegiance, and the share of public sector jobs going to Alawites – already disproportionately large relative to their share of the population before 2011 – has grown. In December 2014, for instance, the government announced that 50 percent of new jobs in the public sector would go to families of “martyrs”, soldiers and members of regime-affiliated militias who die while fighting opposition forces, who are predominately Alawite.

Despite the appearance of normality in regime-held regions, the last five years have seen a significant loss of resources and legitimacy on the part of the government. Reduced funds – the International Monetary Fund estimates that government revenue fell from $12 billion in 2010 to less than $900 million in 2015 – mean, for instance, that the government has not been able to buy large volumes of wheat from farmers in 2015 or 2016.[5] Rather, it has relied on humanitarian aid and imports funded through Iranian credit lines or Russian aid – as well as that provided by international humanitarian agencies. This highlights that the government has lost its capacity to cater to the agricultural constituency, its traditional main base of support, and that its dependency on foreign allies is growing, contributing to the regime’s loss of legitimacy.

In June 2016, the government’s announcement of a subsidy cut on oil products created such anger that a pay rise for civil servants was hastily announced a few days later, erasing all the savings the government had hoped to make.

As the government has responded to the challenge of depleted financial resources and manpower, it has increasingly relied on local leaders and groups to maintain order, gather resources, and project its influence. These include leaders of the government-backed National Defence Forces (NDF) militia, which fund themselves through “taxing” and extorting locals, kidnapping, and looting. While these militias are often loathed because of their criminal practices, they have also gained significant power and influence. The supply of humanitarian aid to besieged areas is a particularly important source of revenue for these militias and their business cronies, who use their presence on the ground to oversee or block the distribution of goods.[6]

In Homs, Saqr Rustom, the head of the local branch of the NDF, the largest regime-affiliated militia, is believed to have more influence than almost any government official.[7] In Aleppo, Hussam Qaterji, a trader who was little known before the war, acts as a middleman for the trade of oil and cereals between the regime and Kurdish areas. He was recently rewarded by the regime through his “election” as a member of parliament for Aleppo.[8]

The presence of these militias, some of which are closely affiliated to Iran and Hezbollah, and which often compete with each other for influence and control of resources, is an increasing source of instability in regime areas. This illustrates that the state does not have full control of all aspects of life in areas under its power. By subcontracting out local governance, particularly in terms of law and order, to these allied local militias, the government has weakened its own position.

On some occasions this has resulted in intra-regime tensions and clashes. In March, for instance, in the Christian town of Sqalbieh, in the countryside of Hama, Philip Suleiman, the head of Quwat al-Ghadab, or the Rage Groups, a militia affiliated to the Republican Guards, was briefly arrested and beaten over accusations of smuggling diesel and petrol. The detention sparked widespread protests, eventually leading to his release.[9] In July, in Mhardeh, the other large Christian town in the Hama province, Fahd al-Wakil, the son of the head of the local branch of the NDF, posted photos of his bruised face after a beating from members of the Air Force Intelligence Directorate, a security agency.[10]

Kurdish areas

Kurdish party the PYD has established an autonomous region in the northeast of the country, around the city of Qamishli and in a pocket northwest of Aleppo, which it calls Rojava, or “western Kurdistan”. This Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) is divided into three districts, or cantons (Jazireh, Kobani, and Afrin), each of which has its own unelected legislative council and executive arm. While in theory the control of some of this area is shared with the regime, in practice it is the PYD that sets the rules of the game – with the exception of Qamishli Airport, which is still under government control. By the end of August 2016, the PYD had also taken full control of the city of Hassakeh.

Since early 2014, the DAA has approved dozens of laws, including a quasi-constitution called “Rojava’s social contract”. New bodies have been established to license business investments, schools, and media outlets, among others, while a communal system for sharing economic resources within the community is being tested.[11] In October 2015, the region’s first university was established in the Afrin district, west of Aleppo, with 180 students.[12] And, in March 2016, the PYD announced a plan to establish a central bank that would be independent of the Syrian Central Bank, although it is still unclear how it would function or whether it plans to issue its own currency.[13]

An entirely Kurdish school curriculum for the first three years of schooling was introduced in September 2015. Children are not taught Arabic at all, raising a barrier between them and all other Syrians, and making it more difficult in the long term for Kurds to gain employment with Syrian state institutions or to relocate to other parts of the country.

Rojava has seen the establishment of various institutions with numerous stakeholders, as well as the emergence of new political leaders who have gained power and visibility, and a broad network of non-governmental associations and military leaders – although most of the leaders of the PYD’s armed wing, the YPG, are believed to be Turkish nationals. The PYD has also established offices in various capitals abroad, including Moscow, Berlin, Stockholm, and Paris, helping to create direct links between PYD leaders and foreign officials.

The reasons for the PYD’s success include its de-facto agreement to avoid confrontation with the regime, its independent sources of revenues from oil extraction – output is estimated at around 40,000 barrels per day, which are used both for local consumption and exported through Iraq’s Kurdistan – and its disciplined and well-structured organisation. The PYD also derives legitimacy from its role as standard bearer of the autonomy for which Kurds have been fighting for decades. Besides oil, Rojava’s economy mostly relies on agricultural production and on international aid, which has been increasing of late; private investment and employment remain limited.

Despite growing autonomy, however, the Syrian state continues to play an important role in Rojava, granting all civil record documents (such as birth, marriage, and death certificates) and paying salaries to civil servants. The fact that the government continues to provide services suits both the regime, as the management of state institutions and the provision of services are an important source of legitimacy, and the PYD, as establishing an alternative administration would have been burdensome. The regime also maintains control of Qamishli Airport, the most significant infrastructure in the area and the only permanent passage in and out; borders with neighbouring states and entities are permanently or often closed, including with the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq. The Syrian regime, and by extension the central government, therefore, still has a number of important means to exercise leverage in its relation to the PYD. Tensions also exist in Rojava between the YPG and regime forces, between Kurds and other ethnic groups, and between different Kurdish groups: the PYD on the one hand, and the Kurdish National Council (KNC), which groups several Kurdish parties close to the National Coalition, on the other.

In September 2015, the Jazireh legislative council passed the Law for the Management and Protection of the Assets of the Refugees and the Absentees, which, in effect, authorises the confiscation of all assets of people who have left the region. Representatives of Christian Assyrians in the Council refused to vote on the text, and the community as a whole felt targeted by the measure. While the law does not explicitly single out any ethnic group, the number of Christians who fled the region is much higher than other groups and they are believed to be better off, so would be more affected by asset seizures than other communities. In a bid to appease the Christian community, but also probably to avoid a backlash with foreign backers – who are very sensitive to the plight of Christians – the PYD eventually backtracked and agreed to hand over any assets seized from Christians to the Church.

Competition with Iraq’s Kurdish Regional Government led by Massoud Barzani, who supports the KNC, has also resulted in tensions, including the regular closure of the Simalka border crossing into the KRG, the only land gateway outside Rojava, leading to regular bouts of shortages and price inflation of goods.[14]

ISIS areas

Often viewed only through the prism of its ideology or terror acts, ISIS has also proved to be a relatively capable administrator of the regions under its control. The militant group, which oversees a population that is uniform from a sectarian and ethnic point of view, has established a system of governance that has helped it raise enough revenue to finance its military operations, maintain a form of law and order, and ensure the supply of a minimal set of services to the population.

Its administration, which encompasses regions across the Syrian-Iraqi border, relies to an important degree on the exploitation of oil and gas resources around the region of Deir ez-Zor. This is possible in part thanks to a de-facto agreement with the regime to run gas-treatment plants and distribute their output to the national grid. It has also developed other sources of income, including taxes on goods and transit, and other forms of extortion.

In Raqqa, the de-facto capital of the “Caliphate” that ISIS has established in parts of Syria and Iraq, the group has established rules to regulate trading activity, including setting out what items can be sold and where, banning the sale of oil products and gas canisters in the street, and obliging shop owners to keep the roads clean.

The relatively large revenues generated from oil and other sources have also encouraged investment spending, including on repair and maintenance of the electric network.[15] ISIS has also established a financial administration, called the Zakat Office, which levies taxes and issues an annual budget, as well as a police force tasked with ensuring the “morality” of the population.

Estimates of the Caliphate’s annual budget, which also includes spending in Iraq, range between $1.5 and 2.5 billion,[16] although it is estimated to have fallen in recent months, as parts of the oil infrastructure have been destroyed in airstrikes by the US-led coalition. In July 2016, ISIS had also reportedly begun to mint and circulate its own currency.

The durability of the ISIS project has been put in doubt by the all-out war fought against it by almost every state in the region, as well as international powers. While there is little clarity on what is happening today in the societies under ISIS control, it would be wrong to believe that destroying the group will simply restore the status quo ante. Indeed, there is little doubting the level of grievances in these areas – dating to well before the beginning of the uprising. Because the oil wealth of Syria’s east contrasted strikingly with its underdevelopment, it is likely that the population will attempt to block a return to central state control of its resources.

Opposition areas

Several features differentiate the regions under the control of the opposition from those controlled by the PYD and by ISIS. One is their fragmentation and extreme localisation. The zones under the control of the opposition are largely located along the main Damascus–Aleppo axis, either in the large rural areas or in the suburbs of the main cities, including Damascus. In the case of Aleppo, they include around half of the city itself.

This fragmentation has led to the emergence of a wide range of authorities, both military and civilian, with no single chain of command. The administration of these areas also suffers from extreme localisation of decision-making; collective efforts and projects between towns in the same region are an uphill struggle.

The project to establish an effective and unified opposition administration has failed. Political and military fragmentation was a main factor in this failure, but so was the regime’s policy of countering, through systematic bombing, anything it feared could be a viable alternative to its own rule. By contrast, Kurdish and ISIS areas have been largely spared. The destruction of Aleppo’s eastern, opposition-controlled half at the end of 2013 and early 2014 is believed to be mainly a consequence of the regime’s fear that the nascent administration developing in this part of the city could emerge as an alternative.

Another feature of administration in opposition areas is that it has to a large extent been driven by donors. This is indeed the area where most non-UN international aid has gone, and also where money from the Gulf has poured into armed groups – though Gulf money has also contributed significantly to humanitarian aid.

Turkey has emerged as the key gateway for much of the economic activity through opposition areas. Because production capacity has been largely destroyed, these areas now largely depend on humanitarian aid, remittances, and imports, all of which come either through Turkey, in the north, or Jordan, in the south. In 2014, Turkish exports to Syria, mostly to opposition areas, were back to their record 2010 level, at $1.8 billion, although they fell slightly in 2015 to $1.5 billion.

Opposition areas are, however, where Syria’s nascent civil society has emerged, where for the first time in more than five decades Syrians have been able to participate in the election of their leaders, even though this is only at the local level and in very imperfect conditions. A variety of new institutions operating in the field of justice, human rights, or economic development have been created, including the Free Syrian Lawyers Association and the Violations Documentation Center (VDC), founded by human rights activist Razan Zaitouneh. In March 2016, an estimated 395 local councils were active across the country. Eventually, these local structures are likely to form the nucleus of future local administrations in a decentralised Syria.

The Syrian state is not entirely absent from these areas, though with time it is growing increasingly thin. For a long time, civil servants still received their salaries provided that they were not affiliated with the opposition, and continued to provide some services. This was a means by which the government sought to continue to project its influence and legitimacy into opposition areas. But with growing strains on the government’s resources these payments have largely stopped, though they continue in some areas, such as Kurdish zones, where Damascus has most interest in preserving a relationship with the controlling authorities.

In addition, opposition areas, unlike Kurdish and regime-held areas, are largely uniform from an ethnic and sectarian point of view – by and large comprised of Arab Sunnis. While there is no formal discrimination against minorities and targeting of them has been limited, the gradual increase in power of Islamist groups has made opposition areas very uncomfortable for religious and ethnic minorities, and some have been attacked or forced out.

Competing ambitions

What still unites Syrians

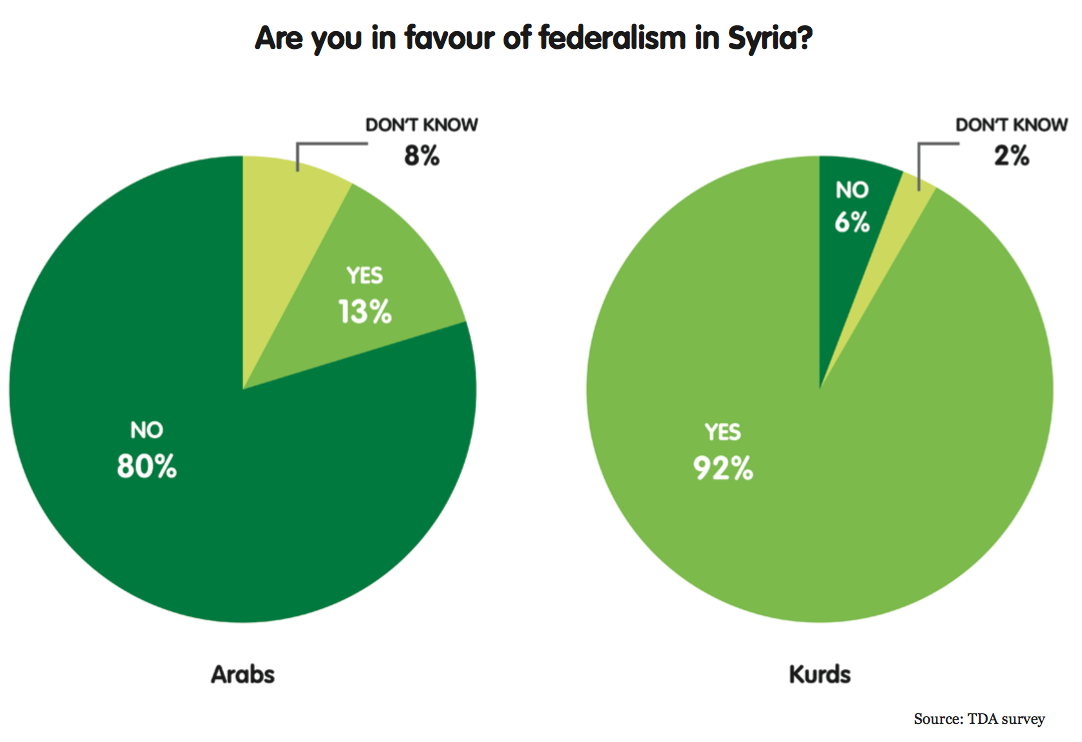

In spite of this daunting picture of division and dispersion, Syrians continue to display a remarkable attachment to their nation. Despite five years of conflict and deep divisions, the only national framework that Syrians from all communities, regions and social classes overwhelmingly continue to recognise is the central state. The one notable exception is the Kurdish area in the northeast (Rojava), where there is a strong demand for autonomy. However, this is not the case for all Kurds, in particular the large numbers that live across the rest of the country. The hundreds of thousands of Kurds living in Damascus, Hama, and Aleppo – Aleppo, not Qamishli, is the Syrian city with the largest Kurdish community – educate their children in state schools, run businesses, are private sector employees, or work as engineers, doctors, and lawyers.

One reason for this strong attachment to the country on the part of most Syrians is that, in spite of the new internal borders, many Syrians continue to travel, exchange, and trade with each other. In pre-uprising Syria, economic inter-dependency between the different parts of Syria was strong. The more developed western part, now under regime control, was dependent for its supplies of oil, wheat and other key commodities (such as gas, phosphate, and cotton), on the less developed eastern part, now divided between the control of ISIS and the PYD. This dependency remains, even if at a lower level than before. Oil and cereals are shipped from the east to densely populated western parts of the country, while electricity produced in opposition areas is distributed to regime areas. Financial transfers are conducted across borders and various goods are traded between the different regions. Manufactured goods, mostly produced in regime areas, continue to be distributed across the rest of the country. Examples of barter deals between regime and opposition areas also abound.

This mutual dependence has played out in surprising ways. In early 2015, for instance, ISIS took control of a gas plant that was under construction by the Russian company Stroytransgaz. Works continued under ISIS control, and the plant now delivers gas to the Syrian grid, which supplies both government and opposition areas. George Haswani, a Christian businessman and owner of a local engineering subcontractor of Stroytransgaz, is believed to have acted as a middleman between ISIS and the government, which led the US government to sanction him.

Several other examples exist of similar deals between parts of the country controlled by the PYD and ISIS, which have the bulk of the resources, and opposition- and regime-controlled areas, where resources are lacking.

As such, while the war has reduced the levels of exchange between Syria’s different parts, it hasn’t erased them. When the war ends, this interdependence will remain.

A further reason for Syrians’ ongoing sense of commitment to the nation is the historically important role of the Syrian state. The state employs hundreds of thousands of people, and provides schooling and health services to millions more. Over the course of the war, it has proved remarkably resilient and efficient, and, amid the destruction and chaos engulfing the rest of the country – of course, largely a consequence of the regime’s actions – the state has proved its value.

The contrast between some still existing state functions in regime-controlled areas and the failure of many attempts at opposition administration has reinforced this sentiment, highlighting the value of a more centralised administration, albeit one free from Assad’s control. Indeed, while local administrative units have sprung up across the country, they haven’t replaced all the functions of the state. The Kurds, for instance, still rely on the Damascus government for the registration of civil records. This is particularly significant given Kurds’ fraught history with Syrian central governments – tens of thousands saw their names erased from the civil records in the early 1960s.

Meanwhile, the internal displacement of Syrians will also encourage a continued sense of nationhood. In the coastal region, for instance, the better-off among those displaced from areas such as Aleppo and Idlib are now buying properties and opening businesses. In the province of Tartous, for instance, the number of new individual companies doubled last year from 867 in 2014 to 1,752. Increasingly, this population sees its future on the coast, and is contributing to gradual demographic change, with a growing Sunni population. These people maintain family, social, and business ties with their regions of origin, contributing to the strong bonds between the various parts of Syria. Likewise, communities of poorer displaced people who have moved to urban centres, often under government control, to escape the violence of outlying areas, maintain strong links to their home regions, which are often opposition ruled.

In the end, the Syrian state is a result of 50 years of nation building by the Ba’ath Party. Decades of a centrally planned economy, the development of national institutions, a single school curriculum, and pervasive regime propaganda have left their mark on Syrian society. The wars against Israel, and the years of economic and political isolation and sanctions, have also contributed to national unity. Syrians remain proud of their history, of their country’s central role in the Arab world, and of its role as a standard bearer of Arabism. This must also be set against the fear of the unknown. Even after all of the destruction of the last five years, the example of the violent disintegration of Iraq frightens everyone.

Where do the parties to the conflict stand?

Many Syrians, across both the opposition and the regime, share the perception that any move towards decentralisation would mean the eventual partition of the country. This being said, the reality of five years of conflict has made clear, at least to some on the opposition side, that major reform of the system of governance is unavoidable.

The National Coalition (NC), which includes most non-armed opposition groups, is proposing administrative decentralisation, i.e. a delegation of central powers to the regions. Some groups in the coalition have suggested that this process could go further, including by granting special political rights to the Kurds, though this would fall short of the Kurdish demand for a federal Syrian state.[17]

At a July 2012 conference in Cairo that brought together all segments of the Syrian opposition, the final statement, which is considered a reference document for most opposition movements, recognised “the existence of a Kurdish nationality among its citizens, with their legitimate national identity and rights according to international conventions and protocols, within the framework of the unity of the Syrian nation”. It committed to ending all forms of discrimination against the Kurds, though it did not enter into the specifics of the future political map of Syria.[18]

However, the NC views decentralisation exclusively through the prism of the Arab/Kurdish divide, and lacks any clear position on a decentralisation process for the rest of Syria. It is also limited by its dependency on Ankara, which strongly opposes any move that would encourage Kurdish separatism within Turkey. In addition, the PYD has close ties with the PKK militant group, which is locked in a conflict with the Turkish state.

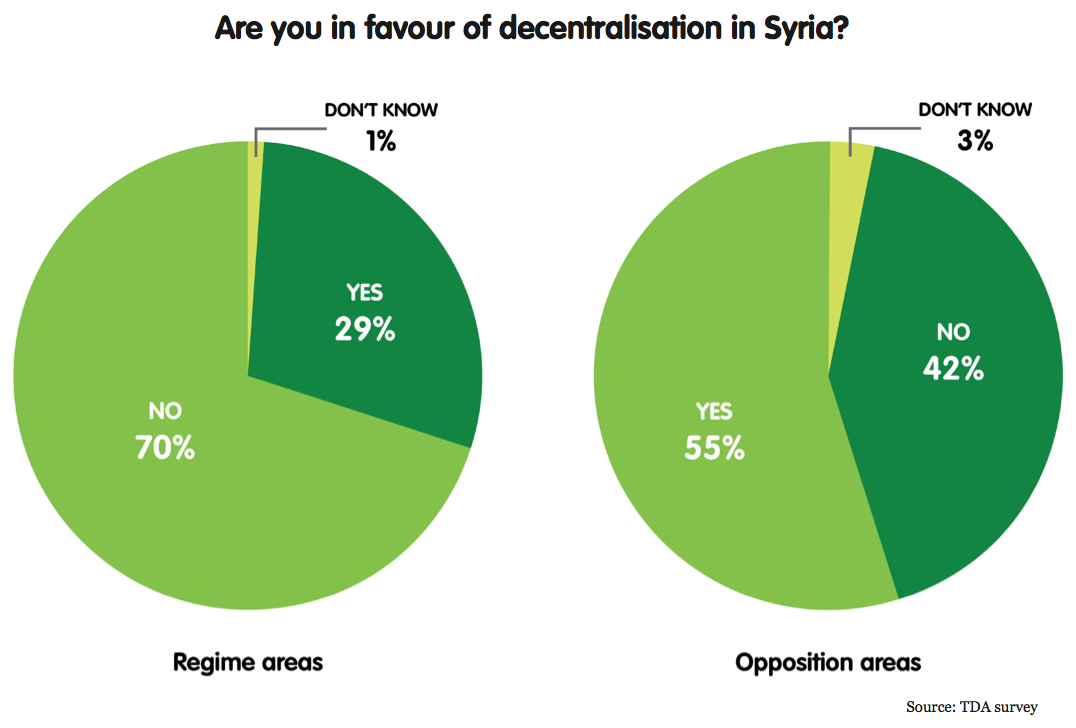

On the part of the regime, there is complete opposition to the idea of decentralisation and no willingness to compromise on the issue. The regime is dominated by the minority Alawite community, and as a result its nationalist credentials are a key source of legitimacy, giving it even less room for manoeuvre on this issue than the opposition. It also fears that once power officially begins to drain away from Damascus, the wider dam will break, leading to the regime’s demise. This is connected to the economic interests of the capital’s economic and business elites, who are close to the regime, and fear losing the power, wealth, and influence that gave them a pre-eminent role in modern Syria. The Syrian state offers the Alawite community in particular the best protection for its interests, both economic and political. It is no surprise, then, that in a recent survey of Syrians’ views of decentralisation conducted by The Day After, an Istanbul-based Syrian NGO, the Alawite community was the group most opposed to decentralisation.[19]

In May 2016, Russia prepared a draft text for a constitution that acknowledged the need for decentralisation. According to extracts published by Al-Akhbar, a pro-regime Lebanese daily, the text called for removing the word “Arab” from the official name of the country, allowing the use of Kurdish language in Kurdish areas, and establishing a regional council with legislative powers that would represent the interests of the local administrations. Much broader powers would be granted to the regions. In addition, the Syrian prime minister would have several deputies representing the various religious and ethnic minorities.[20] Within days, according to Al-Akhbar, the regime rejected almost all the Russian suggestions.

A broad agreement in favour of the most radical form of decentralisation, federalism, exists among all Kurdish groups, including the KNC and the PYD. Though they are political rivals, both groups concur in their demand for greatly extended powers that would allow them to run most of their day-to-day affairs. No Kurdish political group calls for any form of partition, however, and all claim that they want to remain within the Syrian state framework. This is to some extent a reflection of the regional context; any move towards independence would be rejected by almost all countries in the region that have large Kurdish communities, including Iran and Turkey.

Decentralisation: The issues at stake

The last five years of war in Syria have sent its regions off in different directions, with their own forms of governance, laws, and even languages, suggesting that decentralisation may represent one of the few realistic means to chart a way forward, despite strong opposition from the government. Decentralisation would take as its starting point the facts that have been established on the ground, while maintaining the integrity of the Syrian state and satisfying enough of the interested parties.

However, a major problem in the debate over decentralisation has been the poor understanding of what it would entail and the key issues at stake:

Administrative division

Syria is currently divided into 14 governorates, each of which has a capital city, and into smaller districts and sub-districts. Syria remains, however, a highly centralised state with limited devolution of powers to the regions and districts. It will be crucial to decide the basis on which decentralisation takes place. This includes the question of how the rural/urban divide should be handled – for instance, in Aleppo, where this divide is most obvious, should there be a governorate for the countryside separated from the city? The regions inhabited by Kurds do not correspond to the current administrative division – should more power be given to the governorates, the districts, or the sub-districts? Another key question is what terms should determine the transfer of fiscal income from the state to the regions.

Natural resources

Northeast Syria has relatively large oil reserves and grows wheat, cotton and barley in large volumes. It borders the Tigris River, along the border with Iraq, which Syria has never really exploited, but is sufficient to irrigate large tracts of land. Deciding who these reserves belong to – all Syrians or only those who live locally – how they will be developed, and how their revenue will be shared, is at the core of the debate on decentralisation.

The PYD’s meeting in Rumeilan and the rejection of the Kurds’ approach by both the regime and the opposition makes clear that control of the oil resources will be a crucial part of any future negotiations. This applies not just to Kurdish regions, but to other parts of the country with natural resources such as Deir-ez-Zor, the other major centre of oil production.

State economic policy

The allocation of government jobs will be a fundamental issue in a country where the state absorbs around a third of the workforce entering the labour market every year. State investment in infrastructure, health, and education facilities, and business projects is also key. This investment has in the past been aimed in part at reducing geographic imbalances, a role the Syrian government abandoned as it began its liberalisation drive in the early 1980s, affecting the country’s peripheral areas in particular. These issues will come increasingly to the fore in the context of any future post-conflict reconstruction efforts. There will be debate over who should control the purse strings, and whether the funds should be handled by a strong central government in Damascus. If so, the contractors, suppliers, and other members of the business elite that will benefit most will be those based close to the centre of power.

Secularism, ethnic diversity, and community recognition

Although Syria is not a secular state per se, since independence, including during the Ba’athist period, the state has been inclusive of all religious groups, recognising and protecting religious beliefs and practices, and has been religion-neutral on the appointment of senior state employees and government officials. A rare exception is the position of president, from which Christians are banned – as confirmed in the constitution approved under Bashar al-Assad in 2012.

However, when it comes to ethnicity, there is formal discrimination against non-Arabs. Since independence, Arab nationalism has been the political horizon of almost all political parties, and since the Ba’ath Party came to power in 1963 it has become the official ideology of the state. The country’s name is the Syrian Arab Republic – most Arab countries do not mention the word “Arab” in their official denomination – and Arabic is the sole official language and the only one taught by state schools and universities. Because of the size of the Kurdish community and their geographic concentration, and hence their perceived threat to national unity, Kurds have been particularly discriminated against. In the wake of the uprising, other minorities have brought forward claims for recognition, including Assyrian Christians, Turkmens, Circassians, and Armenians.

Given what the country has witnessed over the past five years, it is difficult to imagine that it will be able to function on the basis of “one person, one vote”. Syrians need to acknowledge that the debate over the fears of minorities is justified. Where do the rights of communities apply and where do those of individuals take precedence? How to preserve the freedom and rights of individuals amid the growing role of ethnic and sectarian communities in Syria and build a state in which people are appointed on the basis of merit, not their community, is a question that has yet to be answered.

Some have suggested the establishment of a bicameral parliamentary system in which an upper house would represent sectarian and ethnic communities, to guarantee these groups some form of political representation, while the lower house would be elected on a “one person, one vote” basis.[21] This system would be somewhat akin to the text of the Taif Agreement that put an end to the Lebanese civil war. The draft Russian constitution proposes a similar bicameral system, whereby a Regional Council would represent regions and the government would have sectarian and ethnic representation.

Recommendations

The reorganisation of Syria’s political structure will create a country that is very different from the one that existed before the 2011 uprising, and which is now in its dying days. Syrians, and with them their international partners, will have to confront some hard questions as they chart a way forward. It is clear, however, that there is no going back to the highly centralised state that existed before 2011. This fact has significant implications for efforts to curtail the conflict.

For European states and institutions, particularly those most active in international diplomacy on Syria – the seven European members of the International Syria Support Group: France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, the UK, and the EU – a recognition of the irreversibility of decentralisation should have important implications for their approach to conflict resolution.

International efforts to date have been focused on pursuing a centrally negotiated power-sharing agreement between representatives of the government and the opposition. This approach must be adjusted to take into account the multiple competing power bases that exist in Syria, and the diffusion of power away from Damascus.

European actors need to recognise this reality and push a decentralisation agenda as one of the conditions for negotiations going forward. This will inevitably need to involve the Kurds as one of the key parties on the ground. Russian willingness to put forward a constitution modelled on decentralisation suggests that there is room for international actors to reach agreement around this model as a prelude to securing meaningful local buy-in, which only has any chance of success if explicitly presented as a means of holding the country together, rather than the slippery slope towards partition. It should also be viewed as an important dimension of the anti-IS fight; the offer of enhanced local control and a fairer distribution of state resources represents an important means of trying to rally local support against the group in these areas.

If European states embrace this path, then they have much to offer from the lessons learned from their own historic experiences, both in terms of post-war reconstruction (World War II, Bosnia) and in terms of the decentralised structure of many of European Union countries, such as Spain and Germany.

But ultimately it will be up to Syrians to decide on the level of devolution that will shape the future of their country. The following are some broad ideas for what could be involved in a decentralisation process:

- Syria should adopt a decentralised political system based on the transfer of power away from Damascus and towards the governorate and district levels. Kurdish regions should get a special status with enhanced powers, as part of asymmetric decentralisation.[22]

- While decentralisation is implemented and communities are recognised as political actors, the central state should retain a monopoly on a number of key sovereign attributes including defence, foreign affairs, and the printing of money.

- Syria’s official name should no longer contain the word “Arab”. This symbolic move would be in line with the overwhelming number of Arabic countries, including Iraq and Lebanon, and would send a positive signal to non-Arab Syrians.

- The state should teach all children from minority groups in their mother tongue. In Kurdish areas in the northeast, and Kurdish-majority districts of Damascus and Aleppo, schools should teach in Kurdish as well as Arabic.

- The state should ensure that it uses its available tools to limit geographic disparities in economic development. For instance, access to employment in each governorate should be based on its share of the country’s total population. Where possible, the same rule should apply to public investments.

- Oil export revenue should be reallocated, guaranteeing a proportion equal to each province’s population, on the principle that oil resources are equally owned by the entire country.

- Sectarian and ethnic communities should get some form of political representation at the central level. A bicameral system could be a solution. However, the Russian proposal to appoint government members on the basis of their religious or ethnic affiliation would go too far in terms of institutionalising these divisions, and would be a recipe for gridlock. Instead, community representation should be pushed at the legislative level, in an upper house tasked with monitoring and control and with preventing discrimination. At the executive level, there should be no appointments or allocation of official positions based on sectarian or ethnic affiliations.

While many of these recommendations may only bear fruit in the long term, their implementation should begin now. They are not just recipes for a stable post-conflict Syria, but can weigh towards ending the war. Acknowledging Kurdish and other ethnic minority rights, and guaranteeing a fairer allocation of resources would, for instance, help bring Kurds on board to work towards a negotiated political solution.

Five years after the beginning of a conflict that has already outlasted most expectations, there is no excuse not to be ready when the end finally comes.

FOOTNOTES

[1] “PYD Capitalises on Territorial Gains, Oil Fields, U.S Statements to Move Towards Quasi-partition”, The Syria Report, 22 March 2016, available at http://syria-report.com/news/economy/pyd-capitalises-territorial-gains-oil-fields-us-statements-move-towards-quasi-partition.

[2] “Syrian Government Commits 30 Billion Pounds to Coastal Area and Only 500 million to Aleppo”, The Syria Report, 16 November 2015, available at http://syria-report.com/news/economy/syrian-government-commits-30-billion-pounds-coastal-area-and-only-500-million-aleppo.

[3] “Syrian Regime Pours Billions to Buy Loyalty of Coastal Region”, The Syria Report, 26 April 2016, available at http://syria-report.com/news/economy/syrian-regime-pours-billions-buy-loyalty-coastal-region.

[4] Jihad Yazigi, “Syria’s Implosion: Political and Economic Impacts”, in Luigi Narbone, Agnès Favier, and Virginie Collombier, Inside wars: local dynamics of conflicts in Syria and Libya (Florence: European University Institute, 2016), available at http://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/41644.

[5] Jeanne Gobat and Kristina Kostial, “Syria’s Conflict Economy”, International Monetary Fund, 29 June 2016, available at https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=44033.

[6] “Al-Assad yu’jez ‘an dabt milishiatahu bi reef Homs”, Al-Souria.net, 30 May 2016, available at www.alsouria.net.

[7] Amer Mohammad, “Saqr Rustom, Hakem Homs Al-Mutlaq”, Souriyatna, 9 February 2014, available at http://old.souriatnapress.net/?p=5630.

[8] “Man houa wasit naql Al-Hoboob min manatiq Al-Idara Al-Zatiyeh ila manatiq Al-Nizam”, All4Syria, 25 May 2016, available at http://www.all4syria.info/Archive/316359.

[9] Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “Quwat al-Ghadab: A Pro-Assad Christian Militia in Suqaylabiyah”, Syria Comment, 3 July 2016, available at http://www.joshualandis.com/blog/quwat-al-ghadab-pro-assad-christian-militia-suqaylabiyah/.

[10] Safwan Ahmad, “Najl zaim Al-Shabiha fi madinat Mhardeh”, All4Syria, 17 July 2016, available at http://all4syria.info/Archive/328698.

[11] Janet Biehl, “Rojava’s Threefold Economy”, Ecology or Catastrophe blog, 25 February 2015, available at http://www.biehlonbookchin.com/rojavas-threefold-economy/.

[12] “Kurds open first university in Syrian Kurdistan,” Ekurd Daily, 13 October 2015, available at http://ekurd.net/first-university-in-syrian-kurdistan-2015-10-13.

[13] “A Central Bank for Rojava: A sign of prudence or posturing?”, Syria: direct, 28 March 2016, available at http://syriadirect.org/news/a-central-bank-for-rojava-a-sign-of-prudence-or-posturing/.

[14] “Syrian Iraqi Border Crossing Reopened”, The Syria Report, 14 June 2016, available at http://syria-report.com/news/retail-trade/syrian-iraqi-border-crossing-reopened.

[15] “ISIS Issues Tender to Carry Electrical Works in Raqqa”, The Syria Report, 24 November 2014, available at http://syria-report.com/news/power/isis-issues-tender-carry-electrical-works-raqqa.

[16] “ISIS Financing in 2015”, Center for the Analysis of Terrorism, 1 June 2016, available at http://cat-int.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/ISIS-Financing-2015-Report.pdf.

[17] Interview with senior official in the National Coalition, June 2016.

[18] “The Final Statement for the Syria Opposition Conference”, Cairo, 6 July 2012, available at https://www.facebook.com/notes/us-embassy-damascus/the-final-statement-for-the-syria-opposition-conference/10150925537506938/.

[19] “Syria: Opinions and Attitudes on Federalism, Decentralization, and the experience of the Democratic Self-Administration”, The Day After, 26 April 2016, available at http://tda-sy.org/en/category/publications/survey-studies.

[20] Elie Hanna, “Dustour Roussi li-Souria”, Al-Akhbar, 23 May 2016, available at http://www.al-akhbar.com/node/258466.

[21] Isam Al Khafaji, “A Bicameral Parliament in Iraq and Syria”, Arab Reform Initiative, 1 July 2016, available at http://souriahouria.com/a-bicameral-parliament-in-iraq-and-syria-by-isam-al-khafaji/.

[22] Sean Kane, Joost R. Hiltermann, and Raad Alkadiri, “Iraq’s Federalism Quandary”, The National Interest, March 2012, available at http://nationalinterest.org/article/iraqs-federalism-quandary-6512.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.