EU differentiation and the push for peace in Israel-Palestine

Summary

- The adoption and streamlining of differentiation measures represents a unique and effective European contribution towards Israeli-Palestinian peace at a time in which the Middle East Peace Process in its current configuration has failed.

- Differentiation disincentives Israel’s illegal acquisition of territory and re-affirms the territorial basis of a two-state solution. It also feeds an Israeli debate over national priorities by framing the negative consequences that Israel will face in its bilateral relations if it continues its annexation of Palestinian territory.

- Despite Israeli efforts to erode consensus within the EU, differentiation continues to receive broad support among member states. EU officials must allow the correct, full, and effective implementation of existing legislation and policy positions relating to Israeli settlements

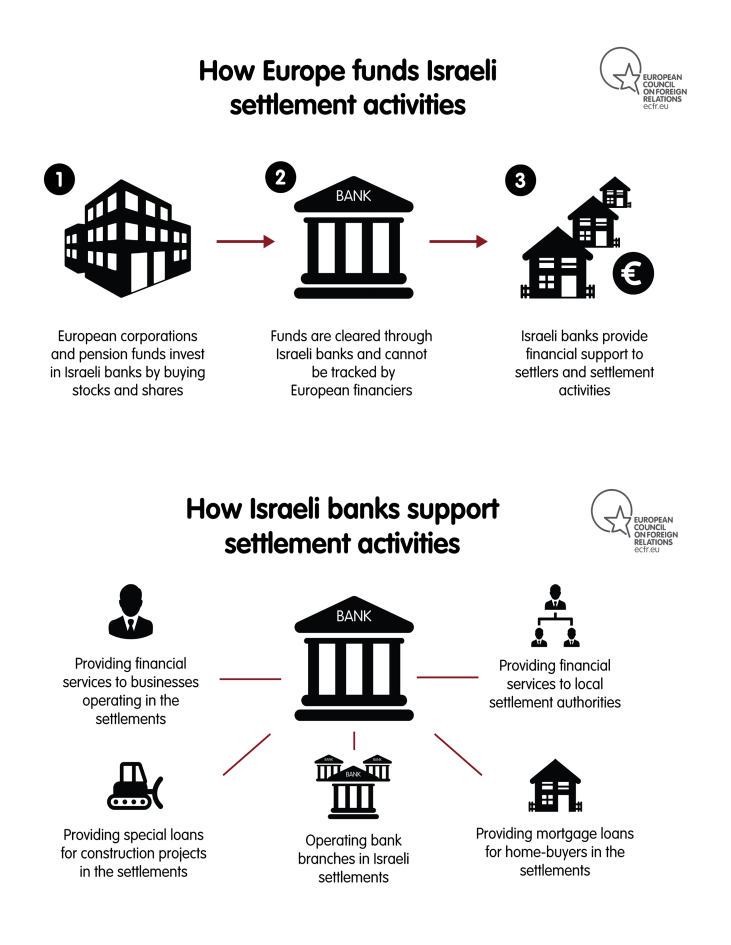

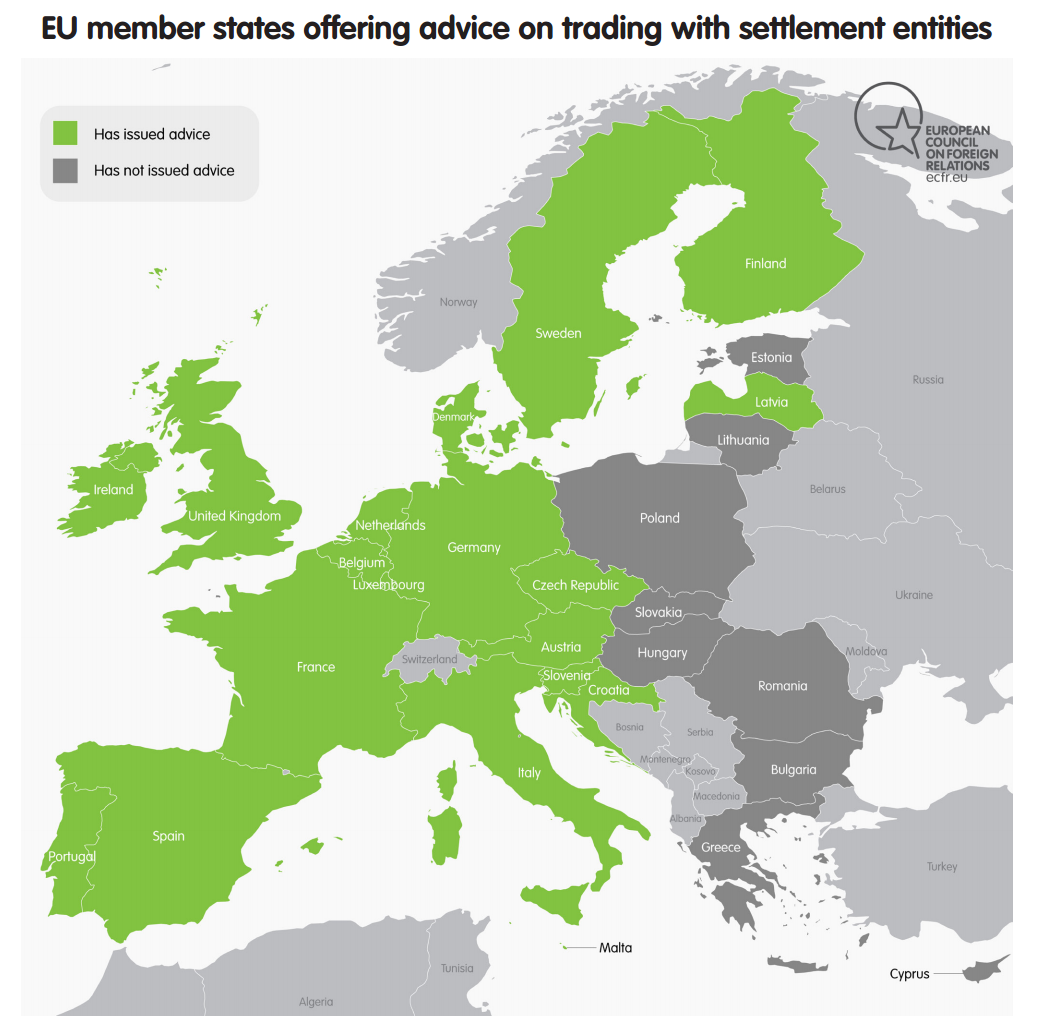

- European entities engaging in financial activity with Israeli settlements – even indirectly – could face serious legal, financial and reputational risks. The EU and its member states should offer more advice on the consequences of doing business with settlement-related entities.

Policy recommendations

- Resist Israel’s settlement creep

- Identify areas in which EU practices clash with domestic legislation

- Monitor Israeli compliance with EU differentiation requirements

- Adopt informed compliance measures by national regulatory authorities

- Clarify the risks of doing business with settlement entities

- Develop a consistent EU position on how to tackle situations of occupation and annexation

- Ensure that EU delegations can monitor human rights compliance of European businesses involved in settlement activities

- Build a European consensus

- Invest more time in understanding differentiation

- Provide a coherent, convincing, and fact-based rebuttal to Israeli accusations

- Consistently articulate the legal necessity that drives EU differentiation

- Develop a European communications strategy

- Strengthen EU engagement with the Israeli public

- Counter Israeli allegations of anti-Semitism

- Spell out the negative consequences that Israel will face if it continues to occupy Palestinian territory

- Reject the possibility of à la carte relations

- Learn the correct story from the US

Introduction

Next year will mark the 50 year anniversary of Israel’s de facto annexation and prolonged occupation of Palestinian territory. The approaching milestone will bring with it a renewed focus on both the failings and future direction of international peacemaking efforts. The lack of any viable path towards a two-state solution in recent years has shown that European policy is increasingly out-of-sync with realities on the ground at a time during which developments in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPTs) and in Israeli politics are moving in the wrong direction.

With the potential for a two-state solution growing increasingly unlikely, the EU’s desire to maintain a “business as usual” approach, predicated on high levels of financial and political investment, and an unwavering commitment to a Middle East Peace Process (MEPP) that has long since broken down, only perpetuates these negative trends.

Even though European leaders accept that the status quo in the OPTs is unsustainable, they fail to offer any course correction. Instead, they continue to repeat the failed choreography that has characterised the last 20 years of peace talks. Among many European policymakers the belief still persists that the Middle East Peace Process, in its current Oslo configuration, offers the path to resolving the conflict. Failing that, they believe the MEPP still represents an effective tool for managing the conflict provided that both sides can be coaxed back into talks. Current dynamics on both sides are increasingly challenging these two beliefs.

While the European Union and its member states frequently reaffirm their commitment to a two-state vision, they shy away from deploying the tools necessary to help make this a reality, or at least maintain it as a viable option. In continuing to promote a broken model, the EU and its member states are punching below their collective weight. Instead of taking the initiative, they continue to act solely as a placeholder in between successive rounds of United States-led diplomacy. Instead of restricting its energies to devising new formats and incentives to push Israelis and Palestinians back into the negotiating room, the EU could be tackling issues head on.

Getting the Palestinian house in order is a priority that the EU needs to push forward with its Palestinian interlocutors given its status as the largest donor of financial assistance. This includes affirming European support for reconciliation, national elections and PLO reform – challenges that will be important to overcome so as to smooth the way towards a future peace agreement. Tackling violence and accusations of incitement on both sides is another important element. But cause and effect should not be confused.

It is Israel’s policy of settlement expansion, the fragmentation of Palestinian territory and the domestic dynamics sustaining Israel’s settlement enterprise that ultimately represent the greatest and most immediate threat to the viability of a two-state solution. As ECFR’s July 2015 report on “EU differentiation and Israeli settlements” argued, EU law provides an effective legal framework for chipping away at the incentive structure that underpins Israeli public support for the occupation.[1]

What is differentiation?

Differentiation refers to a variety of measures taken by the EU and its member states to exclude settlement-linked entities and activities from bilateral relations with Israel. The EU has never recognised the legality of Israeli settlements in the occupied territories (including those in East Jerusalem and the Syrian Golan Heights that have been formally annexed by Israel). This means that the EU has an obligation to practically implement its non-recognition policy by fully and effectively implementing its own legislation against Israel’s incorporation of settlement entities and activities into its external relations with the EU. To do this, the EU must apply differentiation measures. Such differentiation measures can translate into normative power as increased integration and access to Europe requires Israeli compliance with European regulations, policies and values.

While differentiation has broad support among the EU institutions and member states there are clear and committed steps that need to be taken for such an approach to deliver progress. In the aftermath of publishing “EU differentiation and Israeli settlements” the Tel Aviv banking index dropped 2.46 points in response to the report’s recommendation that the EU and its member states review their relationship with Israeli financial institutions that support Israeli settlement activities in the OPTs.[2] This alone indicates the kind of game-changing impact that a more coherent, consistent, and comprehensive set of differentiation measures could have on the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories.

One year on, progress on the application of differentiation has been slow, but important. EU consensus around differentiation has broadened, and European diplomats have taken more concrete steps to own and defend it, which represents a step in the right direction. This memo builds on and updates the 2015 report in an effort to sensitise policymakers to the reflexive regulatory processes that lead to the adoption of effective differentiation measures and, ultimately, a more meaningful European contribution towards a resumption of peacemaking efforts. If the two-state solution is to remain a viable option, then the process of differentiation must be accelerated and streamlined.

Fewer incentives

The EU’s traditional approach to the Israeli-Palestinian peace process has been based on maintaining a framework of incentives. The traditional thinking has been that Israel can be incentivised to moderate its behaviour and move along the path of peace with its Palestinian neighbours. The lack of any real political horizon for ending the conflict 20 years after the launch of the Oslo peace process indicates that this incentive approach has clearly failed.

Efforts to incentivise Israel have meant that, with the exception of EU candidate countries and European neighbours, it now has a higher level of integration within the EU’s fabric than most other countries in the world. This has given it privileged access to a range of free trade opportunities, including in the fields of tourism, technology, security, and education.

In June 2008, the EU offered an unconditional upgrade in relations with Israel within the context of its European Neighbourhood Policy even as it expressed its deep concern over accelerated settlement expansion.[3] Four years later, in July 2012, the EU-Israel Association Council identified a list of 60 areas where bilateral relations could be unconditionally strengthened. Then, in December 2013, the EU proposed a Special Privileged Partnership (SPP) as part of a future peace agreement with the Palestinians.[4] More recently, in June 2016, the EU suggested that an additional interim package of incentives be developed to entice both sides towards peace.[5]

All of this, however, has only fed Israel’s appetite for more carrots without taking any positive steps towards the Palestinians. In fact, Israel’s response to new upgrades has often been one of silence or vindication that continued settlement policies have not undermined its relations with Europe. Neither have all the carrots in the world saved Europe from accusations of anti-Semitism, nor slowed the pace of Israeli demolitions of EU-funded humanitarian projects in Area C and the further annexation of Palestinian land.[6] One Israeli politician, now a senior member of the ruling coalition, even described the SPP as an insult and tantamount to bribing Jews to give up their homeland.[7]

Far from furthering the prospects of peace, the EU’s existing policy further empowers Israeli occupation. Unconditional incentives only breed a sense of Israeli exceptionalism and impunity whilst undermining European credibility. The EU’s policy has encouraged Israel’s belief that the conflict can be managed and the settlement enterprise expanded without incurring any tangible cost to its international relations. A March 2014 poll of Israeli-Jewish opinion found that only 9 percent of those surveyed thought that present measures by European governments, businesses, and consumers would be costly for Israel if the existing situation did not change, including on the settlement issue.[8]

This perception will not change unless Israel’s aspirations, expectations, and understanding of the current reality are adjusted. In the same survey, 57 percent believed that a combination of incentives and disincentives would be the most influential method of getting Israeli politicians to accept a peace agreement with the Palestinians.[9] The lesson for Europe is clear: Introducing fewer incentives and more disincentives into its dealings with Israel is likely to prove the more effective formula for achieving positive change in support of a two-state solution.

More disincentives

While incentives have a poor track record, history has shown that disincentives work. In 1991, US President George H. Bush withheld $10 billion in loan guarantees when Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir attempted to slow peace talks with the Palestinians while building more settlements in the OPTs.[10] The move unleashed a new public debate in Israel over national priorities that forced politicians to consider what was more valuable — building settlements or satisfying Israel’s socio-economic needs. This debate featured front and centre during the 1992 election campaign, and eventually led to the election of Yitzhak Rabin who backed the launch of the Oslo peace process.[11]

Disincentives in the form of differentiation measures have also had an impact. This was publicly apparent for the first time in 2013 when Israel’s research and development (R&D) community risked being deprived of EU funds over their government’s ideological commitment to the settlements. The activation of the EU’s legal machinery, and the resulting implications for Israeli authorities, led those Israelis affected to question national priorities once more. In this sense, the functioning of EU law helps to reveal the contradiction, and indeed the difficulty, of maintaining the settlements and deepening (or simply continuing) relations with Europe.

In July 2016, anxieties over the possible expansion of differentiation to the sphere of EU-Israel financial relations led the Tel Aviv banking index to drop by 2.46 points. As the Israeli business daily, Globes, explained at the time, such worries fed a conversation between Israeli banks and the government: “for the European[s], the settlements include Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, which means that almost all the banks are involved. It is hard to quantify the threat, but it is dramatic, a senior banking source said. The banks said that they could not cope with such a threat and that it would not be right for them to do so. They asserted that the response must be on the governmental level”.[12]

While it is indeed difficult to get a complete picture of Europe’s financial contributions to the settlement project – both direct and indirect – it is possible to get a limited snapshot. Based on data compiled by Profundo, private entities and public bodies in Europe have invested over €500 million in eight Israeli banks. Of these, Norwegian shareholders contribute the most, approximately €200 million, followed by those in the UK and France.[13] Given the fungibility of the financial capital employed by these corporate entities and the fact that Israeli banks play a key role in maintaining and promoting Israeli settlement activities, there is a real risk that European investments facilitate illegal Israeli activities in contravention of international law.[14]

From legal necessity to normative power

Measures to differentiate between Israel and settlement-linked entities offer a way of insulating deepening bilateral relations from the settlements. Differentiation protects the EU and its member states from the harmful effects of Israel’s internationally unlawful acts of annexation, the structural violations that ensue from Israel’s prolonged occupation, and liabilities that such acts attract under international and domestic laws.

Given its grounding in international law and domestic legalisation, differentiation relies on a different logic to the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement. Whereas the BDS movement seeks to isolate Israel diplomatically, economically, and culturally, differentiation targets only the settlements and their roots – and not the state of Israel within its internationally recognised borders.

Differentiation is essentially “reflexive”, in that it is driven by the internal necessity of international actors such as the EU and its member states to protect the integrity and effectiveness of their own legal orders by ensuring that they are not giving legal effect to internationally unlawful acts. The EU and its member states are under an internal obligation to ensure that their actions do not confer recognition of the occupying power’s sovereignty over the occupied territory and to ensure legal compliance by their own citizens and businesses. Simply put, differentiation is based on the EU’s need to uphold a legal imperative.

Differentiation should not be considered a politically coercive action such as sanctions — but rather as the correct, full and effective implementation of EU and member state legislation. Law has, however, been created to disincentive the illegal acquisition of territory and make occupation unsustainable. In doing so, it frames a system of incentives and disincentives that are automatically triggered through the full and effective implementation of a third state’s domestic legislation.

Opportunities for maintaining and intensifying Israel’s privileged relations with the EU are conditional on the appropriate application of differentiation by Israeli authorities and the entities that want to maintain those privileged relations. In order to protect the EU legal order from the harmful effects of unlawful international actions, Israel can only be integrated with and have access to Europe if it complies with European regulations, policies, and values (including respect for the 1967 Green Line). The financial sector is just one area, but it shows how little it would take for differentiation to start biting into much-valued aspects of EU-Israel relations that are potentially exposed to settlement activities. It is by going further down this route that the proper functioning of EU law takes on a normative value.

Israel has attempted to disrupt differentiation by turning it into a political tug-of-war. Nevertheless, history has shown that when the EU has held its line, Israel has eventually chosen to apply its own internal differentiation in order to continue accessing those aspects of its bilateral relations with the EU that it values. This was the case when it agreed to exclude settlement products from its Free Trade Agreement with the EU, and when it signed up to the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme, which excludes Israeli settlements entities. Israel also did this when it vowed to enact its own differentiation within domestic poultry, dairy, and organic production lines in order to meet EU import requirements. Failing to exclude the Israeli settlements in these instances would have jeopardised the benefits and access enjoyed by Israeli entities located within Green Line Israel whose activities are unconnected to the settlements.

Differentiation: Where does the EU stand now?

In the year since the release of ECFR’s policy paper on EU differentiation, there has been a more rigorous – if still limited – application of differentiation in certain areas, at both EU and national levels.

Despite the Israeli arm-twisting outlined below, the EU has held fast to its July 2013 funding guidelines on preventing settlement-entities from accessing EU funds, including through its Horizon 2020 R&D project. By all accounts these funding guidelines have proven relatively effective. In November 2015, the European Commission also issued its long-awaited guidelines on the correct labelling of Israeli settlement products.[15] Their implementation and enforcement, however, has tended to vary between member states.

Member states have for the most part preferred to channel much of their efforts to promote differentiation through EU institutions rather than bilaterally. One notable exception is the Netherlands, which implemented restricted pension payments to Dutch nationals living in Israeli settlements as of January 2016, as mandated by its domestic legislation.

At the same time, European diplomats have shown greater willingness and ability to own and defend differentiation measures, starting with EU High Representative Federica Mogherini in her rebuttal to US Congressional criticism.[16] The EU’s ambassador to Israel, Lars Faaborg-Andersen, has also sought to counter Israeli attempts to contest EU policy, noting that until an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement is reached, the EU “will continue to differentiate between Israel within its internationally recognised borders and the settlements.”[17]

Away from the headlines, a 2015 report by the EU’s heads of missions in Jerusalem provided a number of recommendations to advance EU differentiation, which included the proposal to strengthen efforts “to raise awareness amongst EU citizens and businesses on the risks related to economic and financial activities in the settlements […].”[18] Similar language was echoed in a separate Foreign Affairs Council (FAC) conclusion in June 2016, which recognised “the importance of building capacity both within EU Delegations and Member States’ embassies to work effectively on business and human rights issues, including supporting human rights defenders working on corporate accountability and providing guidance to companies on the [United Nations] Guiding Principles.”[19] The EU’s flagship Global Strategy Review, published the same month, also committed to promoting full compliance with European and international law in deepening cooperation with Israel and the Palestinian Authority (PA).[20]

To date, 17 EU member states have advisories warning their businesses of the legal, financial and reputational consequences they could expose themselves to in dealings with Israeli settlement entities. In addition, the Netherlands maintains a longstanding policy of discouraging business ties with Israeli settlements despite having not published a business advisory.

Elsewhere, UN human rights bodies have considered a number of reports on businesses that profit from Israeli settlements and corporate complicity in international crimes.[21] In March 2016, the UN Human Rights Council mandated the creation of a database of all business enterprises – both Israeli and international – with activities in or related to the settlements.[22] This was followed in September 2016 by an announcement from the International Criminal Court (ICC) that it would consider crimes resulting from the exploitation of natural resources and the illegal dispossession of land.[23]

Unpacking the politics of non-implementation

There is no doubt that there has been a step forward in broadening EU member states’ consensus on differentiation and their understanding of the legal necessity driving such measures. A working draft of the January 2016 FAC Conclusion on the MEPP supported by a majority of member states contained stronger language than previous conclusions. It affirmed a willingness to “unequivocally and explicitly make the distinction between Israel and all territories occupied by Israel in 1967, by ensuring inter alia the non-applicability of all EU agreements with the State of Israel, in form and in implementation, to these territories”.

Despite the rhetoric, Israel has sown discord at the FAC level. It has done so by weakening the resolve of individual member states, knowing that FAC decisions need unanimous support. The January 2016 FAC language mentioned above garnered unanimous acceptance in the Maghreb-Mashreq working group, as well as the support of a majority of member states at the Political and Security Committee (PSC) level, including the Quint (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom). Yet Israel was able to water down the final draft by co-opting a small number of states at the last minute – starting with Greece, followed by Poland, Bulgaria, and Hungary.

EU member state business Advisories on Israeli Settlements

EU member state business Advisories on Israeli Settlements

For a number of states the prospect of enhanced bilateral ties with Israel is incredibly attractive. Greece, for instance, is interested in securing an energy cooperation agreement with Israel (and Cyprus) and is therefore susceptible to political trade-offs on the Palestinian issue to keep Israel onside. However, Israel’s decision to reconcile with Greece’s rival — Turkey — coupled with a largely pro-Palestinian Greek public means that the ruling left-wing Syriza party may not always have the same appetite for defending Israeli interests.

These calculations differ from those of eastern European states that have significantly more pro-Israeli elites and publics. While trade interests have been a factor in shaping these relations, the sense of historical injustice perpetrated against Jewish populations in these countries during the Second World War continues to loom large. As such, there is domestic sensitivity in a number of these states over actions that are perceived to be boycotting or otherwise harming Israel.

Israel has leveraged the same constellation of states to impede and politicise the implementation of the EU’s labelling guidelines by pushing national governments, parliaments, and MPs to vocally oppose the move. Politico reported this backlash at the time: “Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó called the move ‘irrational,’ while the Czech Republic’s Culture Minister Daniel Herman urged countries to ‘reject the efforts to discriminate against the only democracy in the Middle East.’ The Czech parliament passed a resolution urging the government not to implement the decision.”[24] Meanwhile, Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Kotzias was alleged to have informed Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu of his country’s opposition to the labelling of settlement products.[25]

In the Netherlands, political pressure generated by intense lobbying from interest groups and the Israeli government delayed the reduction of pension payments to Dutch nationals residing in the settlements. This despite the decision first being announced in 2002 by the current Dutch prime minster, Mark Rutte – at the time state secretary for social affairs and employment – who explained that social security arrangements with Israel do not apply to the settlements, given Dutch non-recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the OPTs. Over the next 14 years, according to an investigation by the Dutch daily NRC Handelsblad, Dutch ministers sought to quietly obstruct and circumvent the correct implementation of Dutch law in order to continue full monthly payments to Dutch settlers.[26] In doing so, the Dutch government made an exception benefitting Israeli settlements that stood in contrast to its exclusion of other territories such as the Western Sahara and Northern Cyprus – which similarly fall outside the scope of Dutch bilateral arrangements.

Meanwhile, the British and French governments have responded to Israeli pressure by hardening their positions against boycotts of Israel and constraining the BDS movement, mirroring similar developments in the US.[27] While it is quite right for European officials to push back against efforts to equate differentiation measures with BDS, efforts to legislate against the right to boycott send a number of worrying signals. They raise serious questions relating to freedom of expression that extend beyond the Israeli-Palestinian issue; they seemingly belie European support for non-violent Palestinian strategies; and risk misconstruing the legal obligations of third parties when dealing with Israeli settlement entities, including their right to lawfully vet suppliers and investments.

Maximising outcome and consensus

Faced with what appears to be an effective and well-orchestrated campaign by Israel to undermine European policy towards its settlements, one of the challenges to EU decision-makers is how to square the circle between maximising both outcome and consensus at the ministerial level. There is no hard and fast rule on how this should be done. Dealing with the political climate in all 28 member states will always be difficult. Much also depends on the political capital that the obstructing states are willing to sacrifice in order to gain a quid pro quo with Israel, and the leverage that law-abiding states – those understanding the necessity underlying differentiation measures – are willing to exert in order to achieve a consensus that can make such an approach successful.

Israel’s ability to divide and rule among member states means that it will be more difficult to strengthen EU differentiation in future at a political level. Its use of “eastern blockers”, however, has not resulted in a roll back in EU positioning. After all, the member states siding with Israel have relatively little political weight on this issue. For example, although failing to raise the bar in terms of language, the January 2016 compromise FAC text reiterated the most ambitious position articulated by the EU to date.[28]

The broader crisis of legitimacy facing the EU, as has been illustrated by Brexit and the refugee crisis, also hampers efforts towards the full and effective implementation of EU legislation and public policy positions across all member states. This has already led to less cohesiveness among members more generally, as well as to individual states more openly flouting EU rules as power flows away from Brussels — rules including, for instance, respecting the Dublin Regulation on asylum claims. Absent the ability or willingness to bring blocking states into line on the issue of Israeli settlements, more assertive European action is likely to occur through ad-hoc coalitions of the willing. The call by 16 member states for EU guidance on the correct labelling of settlement products is one example of this, and it could be replicated on other issues.

But it is worth remembering that the legal machinery, policy, and legal imperatives driving the differentiation process in most cases already exist. What is needed is not so much new laws or new policies, but the correct, full, and effective implementation of existing legislation and policy positions. Rectifying deficient implementation needs no political justification. And indeed, the European Commission can rectify many of these deficiencies based on its existing FAC mandate without the need for additional approval from the European Council.

Understanding the Israeli pushback

Israeli pushback must be understood within the context of attempts at home and abroad to normalise the occupation and fulfil the vision of a “Greater Israel” through a creeping annexation and management of the conflict. Led by a new generation of right-wingers – many of them within the current ruling coalition – the Israeli government has sought to win international acceptance of its claims over East Jerusalem and the West Bank, and conflate these territories with Israel. Concerted efforts have also been waged against the EU to delegitimise and deter European decision-makers from continuing to differentiate between Israel and its settlements. A prime manifestation of both phenomena can be found in the “stealth campaign” being waged through the US Congress to legislate in favour of Israeli claims and deter EU policy, including in US-EU Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations.[29]

Although Israel had been relatively quiet in response to more consequential measures by the EU – such as those relating to organic, poultry or dairy products – it reacted fiercely to the labelling guidelines. Unlike other more technical measures, labelling offered Israel the prospect of halting or at least delaying the differentiation processes by accusing the EU of anti-Semitic behaviour through comparisons to historical imagery of Jewish suffering.

Israel’s anti-EU campaign was top down, with Prime Minister Netanyahu warning that “we remember history and we remember what happened when the products of Jews were labelled in Europe. The labelling of products of the Jewish state by the European Union brings back dark memories. Europe should be ashamed of itself, it took an immoral decision.”[30] Israeli Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked similarly alleged, “European hypocrisy and hatred of Israel has crossed every line”.[31]

The highest decibels came not just from right-wing politicians and the settlement movement. The same talking points were picked up by the centre-left Labour and centrist Yesh Atid leaders, Isaac Herzog and Yair Lapid respectively, who have taken to championing the legitimacy of settlements to international audiences. Herzog’s equating EU labelling with “an act of violence by extremists” also reflects a lurch to the right in Israeli politics and society, and the mainstreaming of settler ideology.[32] EU and US laissez faire in the face of Israel’s settlement policy is also, in part, responsible.

However, the response of Israeli opposition leaders should not lead to a re-think on the part of Europe. Both leaders have served under Netanyahu previously. Isaac Herzog may also do so in the future, while Yair Lapid is seeking to align himself more closely with the settler movement in anticipation of a future prime ministerial challenge. More fundamentally, all Israeli governments, whether Labour or Likud, have advanced the settlement project. If Israeli policy is to become more pragmatic, the key variable will be what incentive/disincentive structure is in place. Crucial to this will be whether Israel begins to feel consequences for continuing down its current path of not only perpetuating systematic violations of international law through its prolonged occupation, but also undermining and wrongfully interpreting the norms of international law.

Singling out Israel?

There is no denying that the EU continues to dedicate considerable time, money, and energy in dealing with the conflict, reflecting both its historical role and deep commitment to Israel. There is also no denying that Israel has often been treated differently from other states. But far from being singled out for punishment, Israel has consistently been treated with a degree of exceptionalism that has benefitted and shielded it from the full force of international accountability. In doing so, the EU has sought to protect Israel from the necessary consequences that would otherwise arise as a result of the correct functioning of EU law. They have also effectively dragged legal necessity into the political arena and made themselves more vulnerable to Israeli counter-measures.

Nor should it be forgotten that the EU has taken far tougher positions in response to Russia’s occupation and annexation of Crimea. It imposed sanctions on Russian entities, including “restrictive measures” that prohibit EU-based companies from buying real estate and financing Crimean companies, and offering tourism services there. The EU has also prohibited its nationals and companies from selling or buying financial products linked to certain Russian financial institutions.[33]

Yet this has not prevented Israel’s disinformation campaign from promoting the idea that the EU is picking on Israel while allegedly failing to take similar measures when it comes to other “territorial disputes taking place today around the world, including within [the EU] or right on [Israel’s] doorstep.”[34] In doing so, Israel has argued that Palestinian self-determination is no different from the myriad of other independence movements around the world, that the Palestinian territories are disputed rather than occupied, and that, as such, the laws of occupation do not fully apply.

However, very few other territorial disputes are considered by the EU, UN, or indeed a majority of third-party states to involve belligerent occupation. Conversely, the heavy weight of international opinion leaves little doubt as to the status of Palestinian territory – even if advocates of Israel’s settlements may try to claim otherwise.[35] There exists a near unanimity of international consensus and an accumulative body of legal opinion recognising the occupied nature of the Palestinian territories and the illegality of Israel’s actions. No country in the world supports Israeli claims to the Palestinian territories, including the UN Security Council, the EU, and the International Court of Justice. In addition, the state of Palestine has been bilaterally recognised by 136 states in addition to being a member of international institutions and party to a host of international treaties.

As well as the legal requirements that regulate third party interactions with occupied territory, another important driver of EU action that sets the case of the OPTs apart is the potential problem of overlapping jurisdictions. This occurs due to the mutually exclusive territorial scopes contained within the EU’s 1997 Interim Association Agreement on trade and cooperation with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and its 1995 Association Agreement with Israel. The result being that EU-Israel agreements cannot apply to the OPTs as these are instead covered by EU-PLO agreements. This consideration does not apply in the case of the Western Sahara – which critics often point to as apparent proof of the EU’s unfair treatment of Israel – given that the EU and its member states have not entered into any agreements with the Polisario nor recognised the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR).

Nonetheless, a legitimate justification must be put forward for concentrating resources on identifying and repairing the deficiencies in the EU-Israel setting. The intensity of EU-Israel engagement and the correspondingly broad scope and incidence of such deficiencies is one. The additional political good that results from repairing them and the potentially harmful political results of leaving them thus, is another.

What about the Palestinians?

Another key attack on differentiation has been to claim that it causes “serious economic harm to tens of thousands of Palestinians who are employed in factories in Judea and Samaria [the West Bank] under suitable conditions and who bring income home to their families.”[36] The argument that Israeli settlements represent an economic lifeline for the West Bank has been widely debunked. In fact, Israel’s continued occupation costs the Palestinian economy far more than can be recuperated through the provision of cheap Palestinian labour to Israeli settlement businesses.[37]

According to a recent UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) report, the Palestinian economy would be at least twice as large without Israeli occupation.[38] Another report by the Office of the UN Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process highlighted that “severely limited Palestinian access to land and natural resources in Area C of the West Bank continues to constrain economic development and hinder private investment.”[39]

According to the World Bank, permitting Palestinian development and access to natural resources in Area C would add as much as €3 billion (an additional 35 percent) to the OPTs’ annual GDP and lead to a 35 percent increase in jobs.[40] A subsequent World Bank report added that the PA is being deprived of a further €255 million (2.2 percent of GDP) a year as a result of the Paris Protocol, which determines Israeli-Palestinian economic arrangements under the Oslo agreement. In addition, it found that Israel is withholding an estimated €569 million (5.3 percent of GDP) in Palestinian revenue.[41]

Ultimately, it is the Palestinians themselves who are best placed to assess whether EU actions are harmful to their interests. When it comes to excluding Israeli settlement activities from agreements with Israel, EU actions actually fall far short of the full boycott of settlements called for by Palestinian civil society, trade unions, and the PLO leadership. The clear Palestinian consensus is for the EU to do more, not less, to curb settlement activity.

Where next? Pivoting from the French initiative

Looking ahead, there is a danger that an inconclusive outcome to France’s current efforts to re-launch negotiations will lead to yet more incentives being put onto the table or more of the same diplomatic legwork being done in a different format pending re-engagement by the US. This might include European involvement in a regional process led by Egypt, or even acquiescence towards some form of Russian overture. In other words, committing to another process so as to tread water rather than sink.

In some quarters, the failure of another round of diplomatic efforts will almost certainly be met with renewed calls for recognising a Palestinian state. This could potentially lead to a second wave of European recognitions that would build on the momentum achieved in late 2014 following Sweden’s recognition of Palestine. Across the Atlantic, the final few months of President Obama’s mandate could see some form of US re-framing exercise, such as a reaffirmation of parameters to set the track for future negotiations. The Palestinians, meanwhile, will continue their efforts to seek largely symbolic wins in international fora, in addition to pushing for a UN Security Council Resolution on Israeli settlements.

While the potential and usefulness of each track varies, a decision to pursue any of these cannot mean freezing differentiation measures. Without fundamentally challenging the cost/benefit calculations that underpin the Israeli public’s continued support for the status quo, it is unlikely that any of these efforts can create the conditions needed for meaningful talks, nor significantly advance on-the-ground sovereignty for Palestinians or prospects for achieving a two-state solution. Any diplomatic initiative will be more impactful when paired with a clear set of disincentives for those undermining the basis of a two-state solution. The proper functioning of EU law to ensure the non-recognition of Israeli settlements and guarantee the full and effective implementation of EU law grounds such disincentives in a fuller and more effective set of differentiation measures.

Recommendations

Resist Israel’s settlement creep

An unequivocal and explicit distinction must continue to be made between Israel and all territories it occupied in 1967. The European Commission, European External Action Service (EEAS), and member state governments must continue to defend the saliency of the 1967 Green Line by guaranteeing the non-applicability of all existing and future EU agreements with the State of Israel to the settlements. The European and member state parliaments have an important role to play in this regard by upholding the integrity and effectiveness of the EU legal order.

Identify areas in which EU practices clash with domestic legislation

There remain a number of cases of deficient implementation of EU law and public policy that have yet to be fully addressed. However, remedial action in relations with Israel has, until now, tended to be ad hoc and very rarely proactive, with member states often preferring to use the European Commission as a protective shield. In many instances, action has depended on third party instigation and legal challenges to expose and correct instances of deficient implementation of EU law, often after such relations are already in place.

Differentiation can only be more effective if member states commit themselves more fully to implementing their own legal requirements and identifying cases of deficient implementation of domestic legislation. The European Commission must ensure full implementation by member states and follow through on previous decisions it has made, such as those relating to labelling. It must also call out those states that attempt to obstruct the ability of the EU legal order to ensure its integrity and effectiveness once deficiencies have been identified.

Monitor Israeli compliance with EU differentiation requirements

The European Commission should undertake an audit to verify whether Israel has followed through with its commitment to enact and provide institutional guarantees of its own differentiation measures to meet EU requirements, including within Israeli domestic poultry and dairy processing lines.

Adopt informed compliance measures by national regulatory authorities

To ensure that the activities of domestic subjects comply with the legal criteria enshrined in domestic law, state regulatory authorities should issue appropriate guidance consistent with their domestic public policy to guarantee informed compliance by businesses, banks, and pension funds. These informed compliance measures should guide public bodies, private actors and other domestic legal subjects with regards to financial transactions, investments, purchases and procurements in relation to Israeli settlement activities.

Clarify the risks of doing business with settlement entities

European entities implicated in financial or economic activities with the settlements – even indirectly – could face serious legal, financial and reputational risks. The issuing of business advisories by a majority of member states is an important step forward, but more needs to be done to operationalise business advisories and transpose the public policy positions they enshrine into regulatory measures in domestic law. In addition, these advisories should be adopted by national regulatory authorities and should detail the liabilities that businesses may incur in domestic law as a result of trading with businesses operating in or with the settlements.

Member states such as France and the UK that have legislated against boycotts must also do more to clarify that these steps do not alter domestic legislation and longstanding policy positions and commitments in international law, and that they do not infringe on basis rights such as the right to freedom of expression. This includes reaffirming settlement-specific advisories to businesses along with their commitment to implementing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP).

Develop a consistent EU position on how to tackle situations of occupation and annexation

Given the accumulation of EU legal practices towards various situations of annexation and occupation, more attention is needed in exploring how to guarantee the full and effective implementation of EU laws through a principled rules-based approach across the ensemble of the EU’s relations. The trend should be towards enhanced compliance with legal imperatives, not less. To do so may require the EU to further develop its policy positions in international law, including those that concern practices by a foreign authority. The under-examined consequences of Morocco’s activities in the Western Sahara on its relations with the EU and its member states is one example case in point.

Ensure that EU delegations can monitor human rights compliance of European businesses involved in settlement activities

According to the June 2016 FAC conclusions, the European Commission should be tasked with this responsibility. A more robust commitment by member states to the UNGP and the integrity of the domestic rule of law is needed, as is a better understanding of the effects of overseas business activities in settlements, and a greater willingness to raise these issues in political dialogues with third countries.

In line with the EU Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy, the EU and its member states should support companies in respecting their legal obligations when operating in conflict areas.[42] Since the EU and its member states have undertaken to enshrine the UNGP in their public policy, such commitments should be translated into concrete regulatory measures, including in the EU’s external relations. This is important for ensuring that domestic authorities do not give legal effect to internationally unlawful acts and facts, particularly where businesses operate in high-risk situations of structural human rights violations, such as in the OPTs and Western Sahara.

Build a European consensus

While there is not always member-state unity on the Israeli-Palestinian file, the issue of the illegality of Israeli settlements and the European legal obligations to draw a distinction between Israel and the OPTs is something Europe should remain unified on.

Invest more time in understanding differentiation

Maintaining a consensus around the strongest position, or even a coalition of the like-minded, largely depends on having a set of European officials and leaders who are well-versed in the processes and principles that underpin differentiation measures. This means understanding how deficiencies and irregularities can arise within the EU’s bilateral relations, undermining both its public policy and the effectiveness of its domestic law; how existing legal imperatives drive the remedial and corrective processes; how politically counterproductive and legally harmful it is to constrain the functioning of EU law; and appreciating the work that these regulatory processes can perform in support of EU policy positions.

Provide a coherent, convincing, and fact-based rebuttal to Israeli accusations

Emphasis must be placed on solidifying the arguments in favour of differentiation, and going on the offensive against those who are trying to roll back the processes that are underway and block stronger EU action on settlements. This will require countering Israeli efforts to build up a substantive case with which to put Europeans on the defensive, make EU consensus more difficult to attain, and to pick off member states. This will be a key factor in winning over more European decision-makers and determining the pace at which differentiation (and broader EU policy) can be expanded and deepened.

Consistently articulate the legal necessity that drives EU differentiation

European leaders would be able to better protect themselves from Israeli arm-twisting if they clarified that it is not permissible for them to circumvent or interfere with the functioning of the EU’s laws and existing public policy positions to make an exception for Israel. Nor can the EU’s underlying legal obligation to respect its own laws be held hostage to political discretion or coercion. This argument is weakened each time EU officials intervene for political reasons to slow down efforts to address cases of deficient implementation, whether toward Israel, Morocco, or elsewhere.

Develop a European communications strategy

Implement the call for a “comprehensive communications strategy” to widen understanding of EU policy on settlements.[43] Ultimately, it is not enough for the EU and its member states to be seen to implement differentiation. They should match Israeli Hasbara with a stepped-up public diplomacy campaign of their own. Federica Mogherini and others have shown more willingness to defend and explain EU actions vis-à-vis the settlements, but more concerted efforts are needed. To this end, the EEAS’ creation of an East StratCom Task Force to address Russia’s ongoing disinformation campaigns relating to east Ukraine and Crimea is a useful model to explore.

Strengthen EU engagement with the Israeli public

The EU should continue to explain to Israelis the process, drivers, and consequences of differentiation as well as its beneficial effects on the development of EU-Israel relations. This includes continued reaffirmation that while it is committed to deepening relations with Israel, doing so is not compatible with Israel’s (de facto) annexation of, and unlawful exercise of sovereign authority over, Palestinian territory.

The point should be made that beyond being a European requirement, Israelis risk encountering the same issues with other international partners, whether this be the US, Mercosur, or even FIFA. Israeli leaders may counter that new emerging partners in Africa and Asia are less demanding and offer new opportunities, but none of these can fully replace the economic and cultural ties with the West that form part of the identity of many Israelis.

Counter Israeli allegations of anti-Semitism

Those who invoke the Holocaust to score political points should be loudly and roundly condemned. Moreover, not pushing back against ill-founded charges of anti-Semitism would suggest that Europeans think Israeli politicians have a point when they talk of anti-Jewishness, yellow stars, and the darkest days of European history when referencing EU action. It also risks detracting from efforts to counter the genuine threat of a resurgence of anti-Semitism and the pride that European governments take in the close working relations with Jewish communities across Europe in countering real manifestations of anti-Semitism.

Ultimately though, by allowing Israel to define the European actions by default, the EU is missing the chance to make clear that differentiation is not a discriminatory measure but the necessary consequence of Israel’s attempt to integrate economically with Europe while maintaining a settlement enterprise that the EU does not recognise.

Spell out the negative consequences that Israel will face if it continues to occupy Palestinian territory

The settler movement may have become politically enfranchised, but it does not (yet) represent the majority of Israelis who do not necessarily hold the same ideological commitment towards “Judea and Samaria”. Nor do Israeli settlers constitute more than 7 percent of Israel’s population. But it is just as true that regardless of location or beliefs, few Israelis see resolution of the Palestinian issue as a pressing issue.

A comprehensive EU communications strategy should aim to move de-occupation back up the list of priorities by better framing: the long-term risks of prolonged occupation and annexation; the one-state reality that will result; and the impact that this will have on Israel’s international standing.

Reject the possibility of à la carte relations

Within the context of Israel’s fallout in the wake of EU actions toward the settlements and its attempts to exact a political cost by freezing some of its ties with the EU and member states, it must be made clear that bilateral relations come as one package.[44] Israel should not be permitted to cherry-pick the beneficial aspects of its relations with the EU (such as trade and R&D) while freezing those parts that it finds less appealing, such as dialogue on human rights within the OPTs and the peace process.

To do otherwise risks setting a precedent that other countries could seize upon to hold EU legal necessity, or indeed any other decision, hostage to political horse-trading. That Morocco’s decision to temporarily suspend contacts with the EU over the CJEU’s December 2015 ruling on Western Sahara takes a leaf out of Israel’s playbook should come as no surprise.[45] If left unchecked, such dynamics will pose a serious challenge to already low European credibility and its ability to pursue its foreign policy objectives in the region.

The next EU-Israel Association Council meeting should be an opportunity for the EU to re-affirm its legal obligation to differentiate between Israel and its settlements, along with its commitment to freeze any upgrade to the EU-Israel Action Plan pending meaningful progress toward a peace agreement.

Learn the correct story from the US

Israel is fighting EU differentiation via Washington DC, in particular through the US Congress which has criticised EU labelling guidelines for settlement products, used TTIP negotiations to discourage EU action on settlements, and is now considering draft legislation to combat economic pressure targeting settlements and lay the groundwork for imposing sanctions against those who engage in such actions.[46]

Congress’s increased focus on European actions of late shows that at least some in DC and Israel have recognised the potency of the legal tool that the EU has at its disposal. European capitals would do well to recognise this too. They should also appreciate that they have a willing White House partner on their side, for the next few months at least.

Going forward, a second model for the EU’s public diplomacy is the campaign undertaken to secure the Iran nuclear agreement (JCPOA) in which coordinated efforts by the US and European governments were able to contain Congressional spoilers and secure sufficient support for the agreement. In fact, a concerted public diplomacy campaign to better explain European policy positions and the legal process that drives differentiation could potentially find a receptive audience among Congressional Democrats as well as within the US Jewish community. It should, in particular, be remembered that many US Jews also view Israeli settlement construction as contrary to Israel’s security interests.[47]

In any division of labour with the US, one of the most valuable European deliverables remains the EU’s ability to demonstrate clear costs for prolonged occupation and disincentivising the maintenance of the status quo. Promoting a new and more confident European policy centred on legal necessity could have a positive impact, including on the US’s own reassessment towards the conflict by demonstrating the potential usefulness of an alternative approach that is better able to tackle the root causes of the ongoing diplomatic deadlock.

The White House seems to have recognised the useful contribution that the EU can make in curbing Israeli settlement activity. At times it has even appeared to be quietly encouraging and defending such measures. It came out in support of EU labelling of settlement products, for example, noting that it does “not believe that labelling the origin of products is equivalent to a boycott. […] Our long-standing position on settlements is clear. We view Israeli settlements activity as illegitimate and counterproductive to the cause of peace.”[48] President Barack Obama’s comments in Jerusalem in March 2013 that “given the frustration in the international community about this conflict, Israel needs to reverse an undertow of isolation” could also be interpreted as a nod to Europe and other actors not hamstrung by US politics to introduce greater disincentives.[49]

Footnotes

[1] Hugh Lovatt and Mattia Toaldo, “EU differentiation and Israeli settlements”, the European Council on Foreign Relations, 22 July 2015, available at https://ecfr.eu/publications/summary/eu_differentiation_and_israeli_settlements3076.

[2] Noam Sheizaf, “Tel Aviv bank index drops following think tank report on settlements”, +972 Magazine, 22 July 2015, available at http://972mag.com/tel-aviv-bank-index-drops-following-think-tank-report-on-settlements/109160/.

[3] “EU statement on the Eighth Meeting of the EU-Israel Association Council”, the Council of the European Union, 16 June 2008, available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2004_2009/documents/dv/association_counc/association_council.pdf.

[4] “European Council Conclusions on the Middle East Peace Process”, the Council of the European Union, 16 December 2013, available at http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/140097.pdf.

[5] “European Council Conclusions on the Middle East Peace Process”, the Council of the European Union, 20 June 2016, available at http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/06/20-fac-conclusions-mepp/?utm_source=dsms-auto&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Council%20conclusions%20on%20the%20Middle%20East%20Peace%20process.

[6] In June 2016, EU High Representative Federica Mogherini stated that since 2009 approximately 180 EU-funded structures valued at €329,000 have been demolished or confiscated. About 600 structures, worth almost €2.4 million, have been subject to orders for demolition, stop-work, or eviction. See “Answer given by Vice-President Mogherini on behalf of the Commission”, the European Parliament, available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getAllAnswers.do?reference=E-2016-002290&language=CS.

[7] Author interview with senior Israeli Knesset member, Jerusalem, 11 March 2014.

[8] Survey of Israeli public opinion by the Israeli Democracy Index commissioned by ECFR, 30-31 March 2014 (hereafter, Survey of Israeli public opinion, Israeli Democracy Index).

[9] Survey of Israeli public opinion, Israeli Democracy Index.

[10] Clyde Haberman, “Shamir Is Said to Admit Plan To Stall Talks ‘for 10 Years’”, the New York Times, 17 June 1992, available at http://www.nytimes.com/1992/06/27/world/shamir-is-said-to-admit-plan-to-stall-talks-for-10-years.html.

[11] For more, see William Cleveland “The Road to the Oslo Peace Accords: The Madrid Conference of 1991” in A History of the Modern Middle East, (New York: Westview Press, 2000), available at http://acc.teachmideast.org/texts.php?module_id=3&reading_id=1026&sequence=2.

[12] Irit Avissar et al, “Israeli banks surprised by EU sanctions threat”, Globes, 23 July 2016, available at http://www.globes.co.il/en/article.aspx?did=1001055266.

[13] Barbara Kuepper, “Investments in Israeli banks: A Research paper Prepared for Bank Tracks”, Profundo Research & Advice, 24 February 2016, available at http://www.banktrack.org/manage/ems_files/download/investments_in_israeli_banks_banktrack_151020_pdf/investments_in_israeli_banks_banktrack_151020.pdf.

[14] For more on the integration between the European and Israeli financial sectors, see “EU differentiation and Israeli settlements”, the European Council on Foreign Relations, 22 July 2015, available at https://ecfr.eu/publications/summary/eu_differentiation_and_israeli_settlements3076. See also “Financing the Israeli Occupation”, Who Profits, October 2010, available at http://www.whoprofits.org/sites/default/files/WhoProfits-IsraeliBanks2010.pdf.

[15] “Interpretative Notice on indication of origin of goods from the territories occupied by Israel since June 1967”, the European Commission, 11 November 2015, available at http://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/israel/documents/news/20151111_interpretative_notice_indication_of_origin_of_goods_en.pdf.

[16] See Federica Mogherini’s comment, “the EU has decided to make the necessary distinction between Israeli settlements in the occupied territories on the one hand, and Israel within its pre-1967 borders on the other, which has allowed the development of our bilateral relations within the framework of the 1995 Association Agreement” in “Letter to US Senator Ted Cruz and the signatories of the letter of November 9”, 23 December 2015, available at http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/files/live/sites/almonitor/files/documents/2016/HRVP_8_Jan_2016_Letter_to_Senators.pdf.

[17] See Lars Faaborg-Andersen’s comment, “the European Union has been accused of a variety of sins, including today from this podium: anti-Semitism, hypocrisy, immorality, rewarding terrorism, destroying Palestinian jobs. These allegations have been made by people coming from the highest echelons in this country,” in Tovah Lazaroff, “Israel cheapens memory of Holocaust by likening settlement labels to Nazi boycott, EU envoy says”, the Jerusalem Post, 18 November 2015, available at http://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Politics-And-Diplomacy/Israel-cheapens-memory-of-Holocaust-by-likening-settlement-labels-to-boycott-EU-envoy-says-434505.

[18] Donald Macintyre, “Israeli settlements: EU fails to act on its diplomats' report”, the Guardian, 12 July 2016, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/12/israeli-settlements-eu-fails-to-act-on-its-diplomats-report.

[19] “European Council Conclusions on Business and Human Rights”, the European Council, 20 June 2016, available at http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/06/20-fac-business-human-rights-conclusions/.

[20] “Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe”, the European External Action Service, 28 June 2016, available at http://eeas.europa.eu/statements-eeas/2016/160628_02_en.htm.

[21] Compare the June 2013 and January 2014 reports by Richard Falk, the special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session23/A-HRC-23%20-21_en.pdf and http://www.refworld.org/docid/531439c44.html. See also “Report of the independent international fact-finding mission to investigate the implications of the Israeli settlements on the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of the Palestinian people throughout the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem”, the United Nations Human Rights Council, 7 February 2013, available at https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/unispal.nsf/5ba47a5c6cef541b802563e000493b8c/0aed277dcbb2bcf585257b0400568621?OpenDocument.

[22] “Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories”, the United Nations Human Rights Council, 22 March 2016, available at https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/unispal.nsf/0/827CFB704068F7B985257F850071154A.

[23] John Vidal and Owen Bowcott, “ICC widens remit to include environmental destruction cases”, the Guardian, 15 September 2016, available at https://www.theguardian.com/global/2016/sep/15/hague-court-widens-remit-to-include-environmental-destruction-cases .

[24] Vince Chadwick and Maïa De La Baume, “How one phrase divided the EU and Israel”, Politico, 4 January 2016, available at http://www.politico.eu/article/best-before-1967-how-the-eu-labeled-israels-occupied-territories-food-labels-european-commission/.

[25] Raphael Ahren, “Greece set to oppose EU settlement labelling”, the Times of Israel, 30 November 2016, available at http://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/greece-set-to-oppose-eu-settlement-labeling/.

[26] Derk Stokmans and Leonie van Nierop, “Wat gaat er mis als we gewoon blijven betalen?”, NRC Handelsblad, 17 June 2016, available at http://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2016/06/17/wat-gaat-er-mis-als-we-gewoon-blijven-betalen-a1401936. For an English language summary and analysis of NRC’s investigation, see Hanine Hassan, “Why are the Dutch funding settlers in Palestine?”, Al Jazeera, 3 July 2016, available at http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2016/06/dutch-funding-settlers-palestine-160627121422098.html.

[27] In February 2003, France passed the “Lellouche” law, effectively banning boycotts based on ethnicity, nationhood, race, or religion, available at https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/eli/loi/2003/2/3/JUSX0206165L/jo/texte. In February 2016, the British government banned publicly-funded bodies from engaging in boycotts through the issuing of new public procurement guidance, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/procurement-policy-note-0116-complying-with-international-obligations. For an analysis of the UK decision, see Valentina Azarova, “Boycotts, International Law Enforcement and the UK’s ‘Anti-Boycott’ Note”, Jurist, 12 April 2016, available at http://www.jurist.org/forum/2016/04/valentina-azarova-uk-note.php.

[28] The language reads, “The European Union expresses its commitment to ensure that – in line with international law – all agreements between the State of Israel and the European Union must unequivocally and explicitly indicate their inapplicability to the territories occupied by Israel in 1967, namely the Golan Heights, the West Bank including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. […] The European Union and its Member States reiterate their commitment to ensure continued, full and effective implementation of existing European Union legislation and bilateral arrangements applicable to settlement products.” First stated in the European Council Conclusions on the Middle East Peace Process, 10 December 2012, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/224290/evidence-eeas-council-conclusions-middle-east-peace-process-dec-2012.pdf.

[29] For more, see Lara Friedman, “The Stealth Campaign in Congress to Support Israeli Settlements”, LobeLog, 1 December 2015, available at https://lobelog.com/the-stealth-campaign-in-congress-to-support-israeli-settlements/.

[30] “PM Netanyahu’s response to the EU decision regarding product labelling”, the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 11 November 2015, available at http://mfa.gov.il/MFA/PressRoom/2015/Pages/PM-Netanyahu-responds-to-EU-decision-regarding-product-labeling-11-November-2015.aspx.

[31] “Shaked says European ‘hatred’ of Israel ‘crossed every line’”, the Times of Israel, 11 November 2015, available at http://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/shaked-says-european-hatred-of-israel-crossed-every-line/.

[32] Raoul Wootliff, “Herzog tells UK that labeling settlement goods ‘rewards terror’”, the Times of Israel, 3 November 2015, available at http://www.timesofisrael.com/herzog-tells-uk-labeling-settlement-goods-rewards-terror.

[33] For more details on EU sanctions against Russia over Ukraine, see “EU sanctions against Russia over Ukraine crisis”, the European Union, 21 December 2015, available at http://europa.eu/newsroom/highlights/special-coverage/eu_sanctions_en.

[34] Statement from the Israeli foreign ministry quoted by Peter Beaumont in “EU issues guidelines on labelling products from Israeli settlements”, the Guardian, 11 November 2015, available at http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/11/eu-sets-guidelines-on-labelling-products-from-israeli-settlements.

[35] Since the early days of Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory in 1967, Israel has sought to avoid recognition of the applicability of the Fourth Geneva Convention to the OPTs so as to allow for the annexation of East Jerusalem and leave open all options regarding future borders. See “The Comay-Meron Cable reveals reasons for Israeli position on applicability of 4th Geneva Convention”, Akevot, 20 March 1968, available at http://akevot.org.il/en/article/comay-meron-cable/?full#/.

[36] “Herzog: Settlement product labeling is ‘European prize for terror’”, the Jerusalem Post, 3 November 2015, available at http://www.jpost.com/Breaking-News/Herzog-Settlement-product-labeling-is-European-prize-for-terror-431900.

[37] For more, see Nur Arafeh et al., “How Israeli Settlements Stifle Palestine’s Economy”, Al-Shabaka, 15 December 2015, available at https://al-shabaka.org/briefs/how-israeli-settlements-stifle-palestines-economy/ and Dalia Hatuqa, “Palestinians lose $285m in revenues due to Israel deal”, Al Jazeera, 18 April 2016, available at http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/04/palestine-loses-285m-revenues-due-israel-accords-160418153601943.html.

[38] “Report on UNCTAD assistance to the Palestinian people: Developments in the economy of the Occupied Palestinian Territory”, UNCTAD, 1 September 2016, available at http://unctad.org/en/pages/newsdetails.aspx?OriginalVersionID=1317.

[39] “Office on the UN Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process – Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee”, the United Nations, 19 April 2016, available at https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/UNISPAL.NSF/47D4E277B48D9D3685256DDC00612265/F73FFC4A55BAA49085257F95004B1115.

[40] “Area C and the future of the Palestinian economy”, World Bank, 2 October 2013, available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/16686/AUS29220REPLAC0EVISION0January02014.pdf?sequence=1.

[41] “Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee”, World Bank, 19 April 2016, available at http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/780371468179658043/text/104808-WP-v1-2nd-revision-PUBLIC-AHLC-report-April-19-2016.txt.

[42] “Council Conclusions on the Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy 2015 – 2019”, the Council of the European Union, 20 July 2015, available at http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10897-2015-INIT/en/pdf.

[43] Donald Macintyre, “Israeli settlements: EU fails to act on its diplomats' report”, the Guardian, 12 July 2016, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/12/israeli-settlements-eu-fails-to-act-on-its-diplomats-report.

[44] For background, see Barak Ravid, “Netanyahu Suspends Contact With EU Over Israel-Palestinian Peace Process”, Haaretz, 29 November 2015, available at http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-1.689050.

[45] Aziz El Yaakoubi, “Morocco suspends contacts with EU over court ruling on farm trade”, Reuters, 25 February 2016, available at http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-eu-morocco-westernsahara-idUKKCN0VY273.

[46] “United States-Israel Trade Enhancement Act of 2015”, bill introduced by Senator Cardin on 02 March 2015, available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/619. For more information, see Lara Friedman’s round-up of Congressional legislation in support of the settlements, available at https://peacenow.org/issue.php?cat=legislative-round-ups#.WBHc4i0rK01.

[47] “A Portrait of Jewish Americans”, Pew Research Center, October 2013, available at http://www.pewforum.org/2013/10/01/chapter-3-jewish-identity/.

[48] “Daily press briefing with spokesperson John Kirby”, the US State Department, 19 January 2016, available at http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/dpb/2016/01/251415.htm#ISRAEL.

[49] “Remarks of President Barack Obama To the People of Israel”, The White House, 21 March 2013, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/03/21/remarks-president-barack-obama-people-israel.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.