The future shape of Europe: How the EU can bend without breaking

Summary

- Faced with internal and external pressures, the EU is increasingly focused on “cooperation” and “deliverables”, rather than “integration”. ECFR’s research shows that a critical mass of countries agree on the need for more flexible cooperation within the EU.

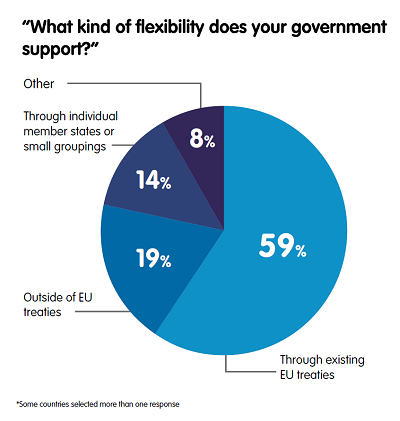

- Many member states believe that more flexible cooperation will help to demonstrate the benefits of collective European action, and to overcome policy deadlocks. There is also a clear preference for flexible cooperation under existing EU treaty instruments.

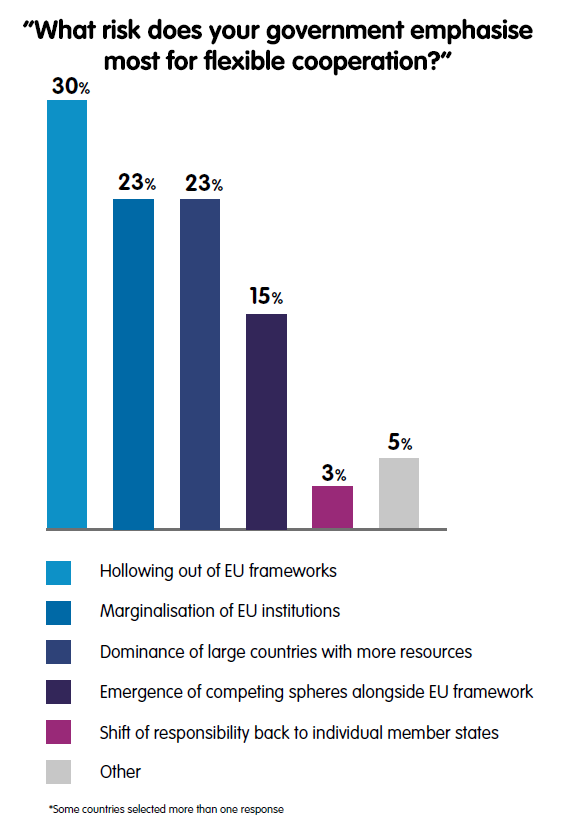

- However, there is a group of swing countries that may not be ready to engage in flexible cooperation just yet. This group is concerned about the risk of the EU framework and institutions being hollowed out, and about the dominance of big countries with larger resources.

- Hungary, Poland, and the United Kingdom, see flexibility as an opportunity to increase national sovereignty in some areas.

- While inclusive approaches are clearly favoured in EU capitals, continued pressure to deliver might push core countries towards even looser types of flexible cooperation in a style reminiscent of Schengen.

Summary

- Faced with internal and external pressures, the EU is increasingly focused on “cooperation” and “deliverables”, rather than “integration”. ECFR’s research shows that a critical mass of countries agree on the need for more flexible cooperation within the EU.

- Many member states believe that more flexible cooperation will help to demonstrate the benefits of collective European action, and to overcome policy deadlocks. There is also a clear preference for flexible cooperation under existing EU treaty instruments.

- However, there is a group of swing countries that may not be ready to engage in flexible cooperation just yet. This group is concerned about the risk of the EU framework and institutions being hollowed out, and about the dominance of big countries with larger resources.

- Hungary, Poland, and the United Kingdom, see flexibility as an opportunity to increase national sovereignty in some areas.

- While inclusive approaches are clearly favoured in EU capitals, continued pressure to deliver might push core countries towards even looser types of flexible cooperation in a style reminiscent of Schengen.

Introduction

The idea of adopting “flexible” modes of cooperation – as opposed to all countries moving at the same speed on the same issues – is a longstanding subplot in the European story of ever-closer union. Over the years, various, often diffuse, concepts of flexibility – “variable geometry”, “Europe of two or multiple speeds”, “core Europe”, to name just a few catchwords – have made their appearance in the debate on the future shape of Europe in both political and academic circles.[1]

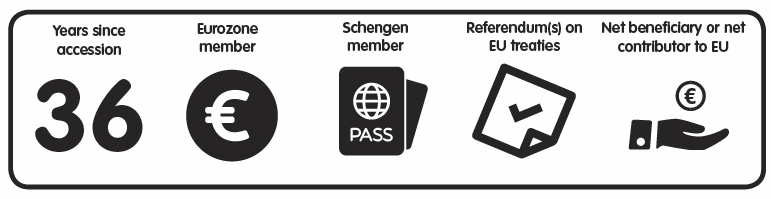

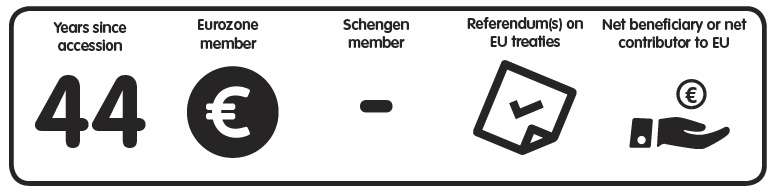

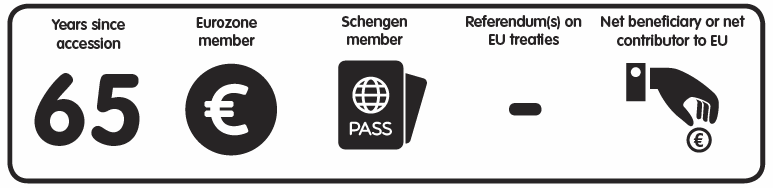

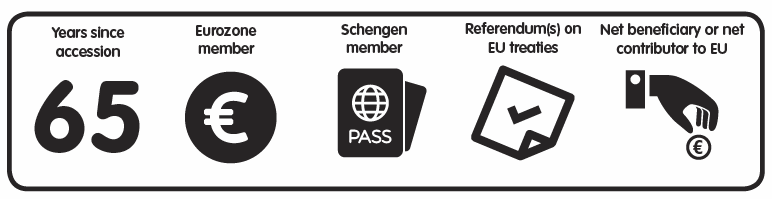

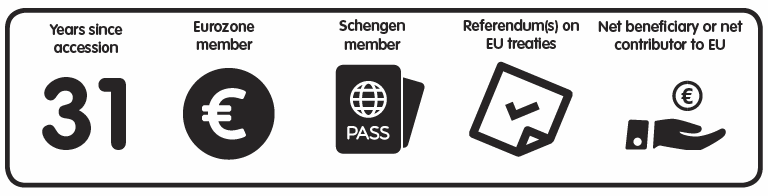

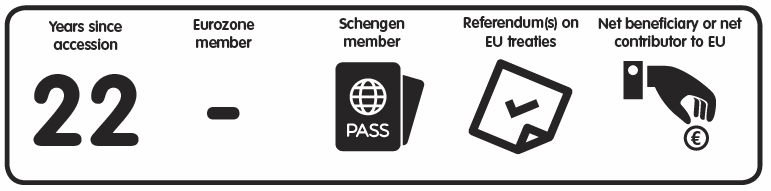

Indeed, out of the notion of “flexibility” have emerged some of the most significant forms of integration in Europe, most notably the eurozone and the Schengen area. While the single currency has been part of the EU’s legal framework right from the start, the Schengen model was different. The Schengen agreement on the abolition of border controls was officially established in 1985 separately from the European Economic Community (EEC) by five of its members (the Benelux countries, France, and Germany). The agreement gained traction over time among other members, and the growing Schengen area was incorporated into EU law 12 years later with the Amsterdam treaty.

Now, with the EU facing internal and external pressures which, under some scenarios, imperil its very survival, a new round in the debate over whether flexibility can ease the EU’s travails has emerged in European capitals. In February 2017, German Chancellor Angela Merkel told reporters at the Malta Summit: “We certainly learned from the history of the last years, that there will be as well a European Union with different speeds that not all will participate every time in all steps of integration”.[2] In early March 2017, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker presented a white paper with five options for EU-27 cooperation after Brexit, including one of greater flexibility, to be discussed at the Rome Summit in late March which will commemorate 60 years of the Treaty of Rome.[3] Against the backdrop of unprecedented challenges to European prosperity, security, and cohesion, EU leaders will want to leave a sign of strength by mapping out the way forward. Ahead of Rome, French President François Hollande convened a meeting with his counterparts from Germany, Italy, and Spain in Versailles on 6 March. There, the four leaders expressed their conviction that different speeds would re-establish confidence among EU citizens in the value of collective European action. But modes of flexible cooperation carry with them the risk that they might accelerate disintegration rather than strengthen collective action in core policies. Such an outcome runs directly counter to the main argument for greater flexibility – namely, to deliver better results in a union of ever more voices. It is a more than valid question to ask how much asynchrony an ever-closer union can handle.

In order to guard against such a deleterious course of events, over the past quarter of a century, EU governments have sought to incorporate methods of flexibility into the European treaties themselves. With the general instrument of “enhanced cooperation”, and “permanent structured cooperation” (PESCO) in the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy, for example, member states acknowledged flexibility as a feature of the EU’s institutional design.

Enhanced cooperation was devised with the Amsterdam Treaty, signed 20 years ago in 1997, and revised in successive treaty reforms in Nice and Lisbon. Enhanced cooperation is stipulated as a procedure whereby a minimum of nine EU countries are allowed to establish advanced cooperation within the EU structures. The framework for the application of enhanced cooperation is rigid: It is only allowed as a means of last resort, not to be applied within exclusive competencies of the union. It needs to: respect the institutional framework of the EU (with a strong role for the European Commission in particular); support the aim of an ever-closer union; be open to all EU countries in principle; and not harm the single market. In this straitjacket, enhanced cooperation has so far been used in the fairly technical areas of divorce law and patents, and property regimes for international couples. Enhanced cooperation on a financial transaction tax has been in development since 2011, but the ten countries cooperating on this have struggled to come to a final agreement.

PESCO allows a core group of member states to make binding commitments to each other on security and defence, with a more resilient military and security architecture as its aim. It was originally initiated at the European Convention in 2003 to be part of the envisaged European Defence Union. At the time, this group would have consisted of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. After disagreements on defence spending in this group and the referendum defeat for the European Constitution which meant the end of the Defence Union, a revised version of PESCO was added into the Lisbon treaty. This revised version allows for more space for the member states to decide on the binding commitments, which of them form the group, and the level of investment. However, because of its history, some member states still regard it as a top-down process which lacks clarity about how the groups and criteria are established. So far, PESCO has not been used, but it has recently been put back on the agenda by a group of EU member states.[4]

While the treaty-driven logic of flexibility has so far not lived up to expectations, can Schengen-style approaches – international treaties of EU members concluded outside of the EU framework, with the perspective of a later inclusion and expansion to other EU members – be devised in the present day? Could it strengthen European cooperation in areas where groups of EU members wish to move ahead more quickly than others?

Against this background, the European Council on Foreign Relations’ new research project set out to understand attitudes towards different forms of flexible cooperation. This included, in particular, foreign and security policy and the potential use of PESCO in this area. This is a current focus of discussion inside the EU and across member states. ECFR’s team of researchers, based in all EU capitals, conducted more than 100 interviews with government officials and experts at universities and think-tanks across the 28 member states. They questioned respondents about member states’ attitudes towards different types of flexible cooperation, and explored whether there have been recent changes in attitude regarding the tension between “effective functioning” and “disintegration”. They then asked what specific projects in foreign and security policies member states believe are worth exploring. The research on which this publication is based reflects the discussions in European capitals by February 2017.

The findings show that overall commitment to EU membership remains strong. In a number of member states it has even intensified in the light of the UK’s referendum vote to leave and the election of Donald Trump. The fact that numerous member states are considering a “Europe of different speeds” or a “flexible union” is not necessarily a sign that the EU is in the stages of further disintegration. On the contrary, the research detected no appetite among member state governments, or publics at large, for abandoning the EU as their preferred model of regional order. Instead, out of the crises has comes a search for new ways to improve how the EU works.

What form of flexibility, therefore, might member states settle on in the current environment? Are there signs of convergence in thinking? Will a core group lead the way in pursuing deeper integration, or cooperation, or will a small number of “rebel” member states use “flexibility” to pursue fragmentation?

This new research by ECFR shows that the will is there but the way remains very much a work in progress. What, in the end, can it tell us about the future shape of Europe?

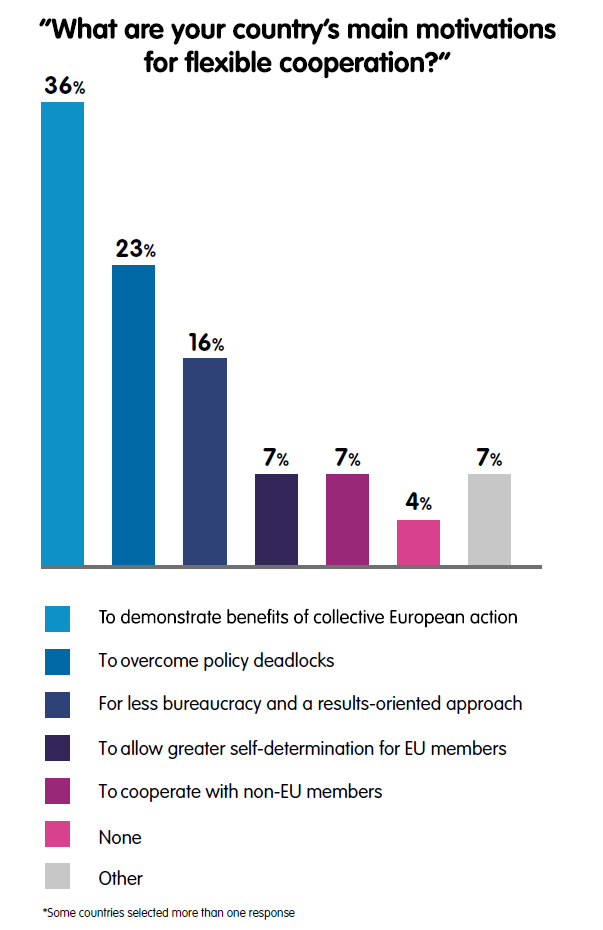

Attitudes towards flexible union

The results of the research show that the past decade of crises and the weakening of the collective action of the EU have left their marks. Asked why a member state would embrace a flexible union, respondents in almost three-quarters of countries pointed to the potential to demonstrate the benefits of collective European action to win back trust in the EU. There are two elements to this. On the one hand, member states feel pressure from their citizens to point to the benefits of collective action rather than struggle on with a perception of a union unable to act. On the other hand, political elites themselves have started to question the real added value of collective action if efforts do not yield results.

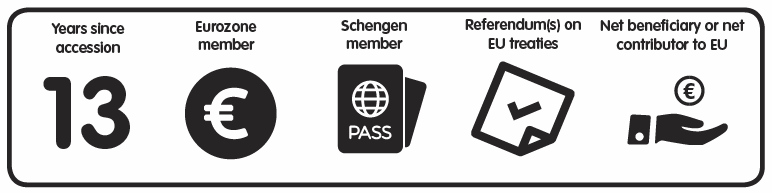

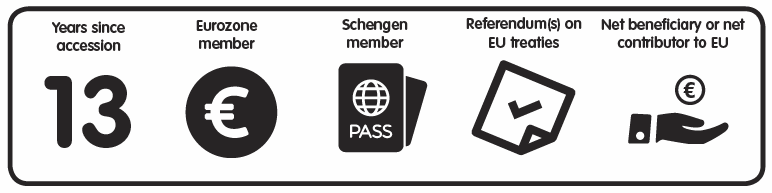

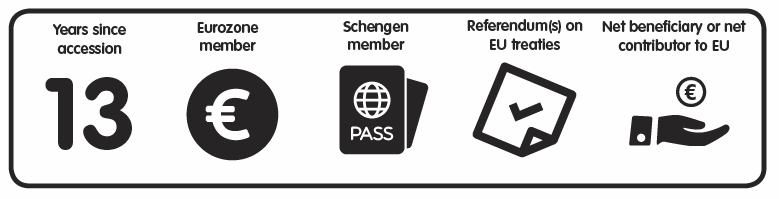

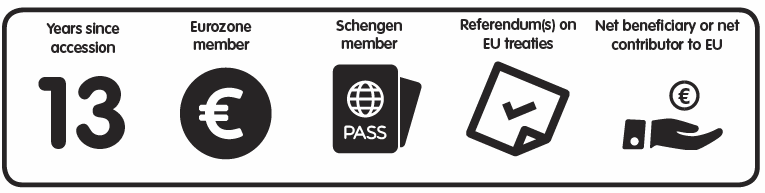

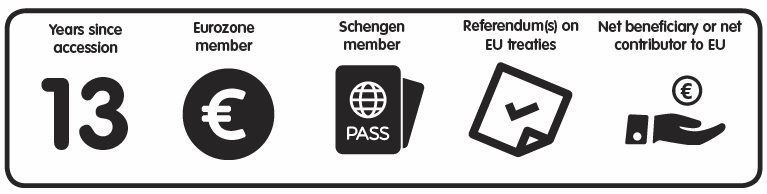

Thirteen countries surveyed also agreed that “Overcoming deadlocks in relevant policies” was a key factor in the growing interest in a flexible union. In this case, one needs to keep in mind the hugely formative experience of deadlock on EU governments over recent years. Meanwhile, nine member states believed “Focusing on results in a less rigid institutional and legal EU framework” to be relevant on this question.

Having said that, the research reveals that two countries, Denmark and Greece, see no real advantages in flexible cooperation, as they fear further flexibility would lead to more disintegration. This is an attitude that indeed still resonates more widely across EU capitals. These countries see flexible cooperation as too much of a departure from the objective of a cohesive union.

In response to the question of whether their national government believes that opportunities of flexibility outweigh the risks, or the other way around, no clear picture emerges – 12 are undecided, 11 have an overall positive take, and five countries point to the risk of even stronger centrifugal tendencies. A major theme emerging in all three groups when asked what the main risks of flexibility are, is the clear concern about the overall cohesion of an already stretched union. Lastly, there is also a group of four countries (Austria, Hungary, Poland, and the UK) that see flexibility as a way to “restrengthen national sovereignty on core policies”.

Austria is a bit of an outlier in this group, as it overall shares the vision of strengthening European integration, including the supranational institutions. However, its motivation for embracing flexibility may be explained by its experience of the refugee crisis. During the crisis Austria found itself very exposed to migration, and could see no joint EU action on the horizon to mitigate that exposure. Indeed, it lasted until Austria took unilateral action. At that time, flexibility, understood as subgroups making decisions on their own (possibly even outside of the treaties, which is an option Austria favours), might have provided an easier way out of the EU deadlock.

When asked about any recent shifts in attitude towards flexible cooperation, researchers report that a number of capitals feel that, given the ever growing pressure for EU policies to be clearly seen to be delivering results, flexible ways of cooperation – even outside of the EU’s institutional framework – should be given a try. This is the message communicated by research on Croatia, Finland, Germany, Italy, Latvia, and Spain. In general, France is sceptical about anything that might undermine the EU and its institutions, particularly given the reality of Brexit. But France nevertheless retains a strong interest in a union that can function effectively and is therefore not closed to looking at new ways of working. The Benelux countries, which were all founding members of the EEC, are also sceptics of flexible cooperation. In their contribution to the Rome Summit in March 2017, they conceded that flexible formations might be necessary in some form in order to ensure progress on areas “that affect member states in different ways”.[5]

Analysis of what kind of flexible cooperation European capitals support reveals a contradictory picture. A large majority – almost four-fifths of all countries – favour “cooperation based on instruments provided in the EU treaties”. A clear minority believe, at one extreme, that their member state government prefers looser cooperation outside of the EU before pursuing a Schengen-type transfer into the treaties at a later stage. At the other extreme, even fewer sense that their national government’s preference is to support the idea of a small coalition of powerful states, or even individual states that could lead initiatives for others to follow.

It is particularly striking that the option that has proved the most legally rigid over recent years – cooperation based on enhanced cooperation or PESCO with all the institutional constraints involved – is still the most preferred type of flexibility.

Of all things, this kind of flexibility has hardly been used and cannot be said to have contributed to what EU capitals currently regard as the main objective: to achieve better performance in the EU framework. ‘Deliveringʼ, however, is seen as the main objective of flexibility in EU capitals at the moment. So how can this contradiction be explained? EU capitals are well aware of the potentially divisive nature of flexibility, especially when organised outside of the legal framework of the EU. This makes countries want to stick with a ‘less flexible flexibility’ – one which in their view has the greatest chance of keeping the EU framework intact. At the same time, a number of capitals have come to acknowledge that the current political and security environment has created a ʻSchengen-typeʼ moment to foster cooperation among a group of countries and explore moving ahead outside of the treaty framework.

Finally, one recurrent fear among member states is that flexible cooperation could lead to big countries dominating smaller ones thanks to their better resources. This was the main worry in no fewer than 13 countries. Three of these countries specifically cited dominance by Germany (Greece, Estonia and Poland), though perceptions of Germany’s role are mixed. For example, in Sweden, Germany is perceived to play a constructive and helpful role. Against this background the recent Versailles summit of France, Germany, Italy, and Spain is remarkable. No doubt the four capitals are well aware of the reservations in other EU countries about being dominated by the larger members. But they nevertheless chose to forge ahead, confident that they constitute a critical mass and that their action is likely to bring others along. While the four leaders stressed that their meeting was an expression of their countries’ responsibility to lead the way for Europe now, this latest initiative should also be taken as a tentative warning. In such a gathering, until only recently Poland would have been around the table as a natural invitee, especially since one of the main issues discussed was European security which is of major concern to Warsaw. This can well be understood as a message to Poland, as well as to other capitals at loggerheads with the union’s values, that core countries were ready to be more decisive in securing their interests – even if that meant leaving others behind.

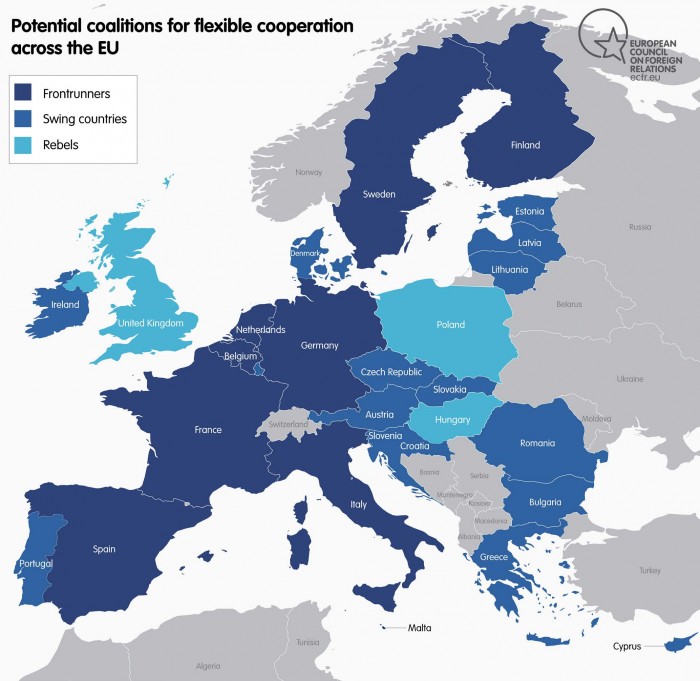

Coalitions on flexible union

Across Europe, views on the prospect of a more flexible union are far from united. Overall, one-third of countries believe that flexible cooperation will strengthen European collaboration, while one-fifth fear that it will strengthen centrifugal tendencies. The rest are either sceptical but believe the evolution into flexible cooperation is inevitable, or they are cautiously optimistic but keen to attach conditions to any new forms of cooperation. Can we identify trends of thought among the 28 member states? How might they be grouped together in order for us to better grasp the current range of views?

The frontrunners

The countries that would lead in any newly formed flexible groups are likely to be larger countries that are already fully integrated into all current EU structures. This group would include the founder members of the EEC (apart from Luxembourg) as well as Spain, which joined the recent ʻVersailles groupʼ. The grouping could possibly include some of the affluent Nordic countries (Finland and Sweden) and Austria, too. The findings show that these countries worry less about the dominance of large countries in a flexible union, but they are concerned about the marginalisation of joint EU institutions. All countries which would participate in this leading group are motivated by the chance to overcome deadlocks and demonstrate the benefits of collective action. This group is also relatively more likely to support cooperation outside of the treaties.

What topics would they like to move ahead on? Among these countries there is an emphasis on economics and trade as core areas on which the EU should lead in general. At first, security and defence figure relatively low down on these countries’ agenda for the EU. But this situation is quickly changing.

As part of this group, France is an interesting case. It is among the countries that has embraced a stronger role for strengthening the EU in European security and defence. But it argues that there is no time for rigid, treaty-based instruments that put further strain on the EU institutions and which do not pay off in the short term. France is indeed interested in finding ways of bringing about quick wins. It is likely to argue for a political approach and looser modes of flexible cooperation.

Lately, Germany too has become more open to this option, though by tradition and conviction it still prefers a treaty-based approach. As for Spain and Italy – the two remaining Versailles group countries – both have traditionally been more concerned about preserving the EU’s institutional framework at large. But they have come to see the need for action in a more urgent way, in particular on European security.

The swing countries

This is a diverse group of countries that may be less able or willing to join the frontrunners in their flexible projects. Less affluent member states, mostly net beneficiaries of the EU, as well as some of the newer and smaller member states, are worried about falling out of flexible groups. On the whole, most members of the group would not block flexible cooperation. But they do not applaud it either. The overwhelming majority of the 28 member states prefer flexible cooperation within the treaties – this is an even more pronounced preference among this group. These countries would be resistant to fundamental changes to the EU’s modus operandi.

Most sceptical are Cyprus, Denmark, Greece, Luxembourg and Slovenia, where the overall response to flexible cooperation is the fear it will strengthen centrifugal tendencies in the EU. In Cyprus, the prospect of a homogeneous union is still seen as paramount, and a multispeed Europe is viewed as a possible catalyst for disintegration in Europe. In Denmark, referendum-based opt-outs on security and defence and other issues have shaped the Danish view on EU cooperation. The government in Copenhagen is worried that the EU could fracture even more at this time of crisis if a more specialised and formalised division of the EU occurs – leaving Denmark in an unfavourable position. In Greece, where the economic crisis is always front and centre of the debate about Europe, the main concern is that initiatives leading to a flexible Europe might leave Greece behind at last, as the country fails to apply bailout terms and re-access international markets. The smallest founding member, Luxembourg, is most sceptical of the concept of the flexible union, thinking the union should only address the changes it is facing collectively. In Slovenia, flexible cooperation is seen as an option only to be considered if nothing else works, because of worries about policy coherence and European unity.

Apart from these more outspoken sceptics, there is a large group of countries that is undecided, or currently not in a position to join the “frontrunners”. The Portuguese government, for example, does not reject the notion of flexible cooperation outright, but it has made clear that this cannot be a synonym for an EU of the powerful versus an EU of the weak. Like Denmark, Ireland is a country that has taken advantage of the flexible integration pathway in the past, and has experienced enormous economic benefits from its EU membership. The government also expects some more creative integration after Brexit due to its special relationship with the UK. However, it too is sceptical of flexible integration and cooperation becoming the norm rather than the exception. Countries like Croatia, Romania, and Slovakia think flexible cooperation will strengthen European cooperation, but because of their status as relatively new and less economically resilient members they might not be willing or able to lead on flexible projects.

The rebels

The last group is willing to support a flexible union – but for reasons markedly different to those of the leading group. Hungary, Poland, and the UK all look on a restrengthening of national sovereignty as one of the main advantages of more flexible cooperation. All three support doing this outside of the EU treaties. In fact, this situation is likely one of the key drivers behind the desire of the “frontrunners” to push ahead: they want to counter the “rebels”.

Hungary aims to increase its role and competitiveness in the EU, avoid passing more sovereignty upwards, and renationalise where it suits its own interest. Flexible cooperation would support this approach. In Poland, the EU is seen as an umbrella that should open and close depending on Polish interests. Both countries are in favour of working methods that sideline the European Commission, as would be the case in cooperation outside of the treaties. Both countries have come into conflict with the European Commission because of domestic developments that clash with EU norms on human rights and democracy.

The UK has always supported the philosophy that the route to a strong EU is through a more flexible union. It has held that flexibility goes hand in hand with restoring sovereignty in key areas. As a large country, and with an overall sceptical attitude towards the EU institutions, the UK is not concerned about EU institutions becoming marginalised or stronger countries dominating others. The only disadvantage it foresees is a more complicated regulatory framework if new initiatives outside of the treaties also require regulations. At present, the UK is already looking at the prospect of a more “flexible union” through the eyes of an EU outsider. In future, the country will probably support flexibility as a means of remaining involved in some EU initiatives as a non-member.

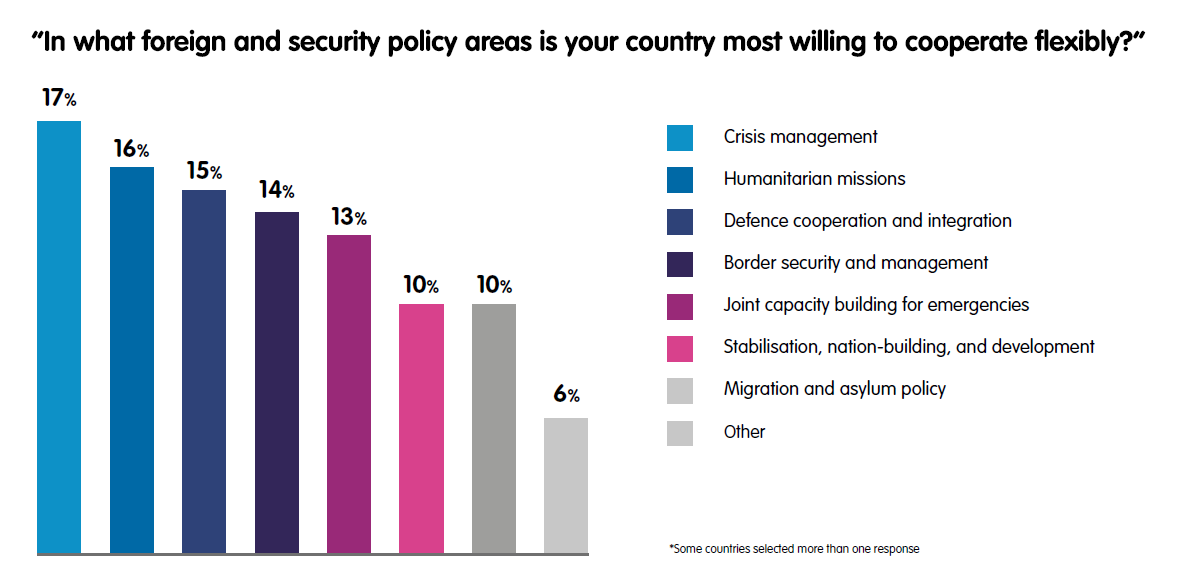

Potential for flexibility in foreign and security policy

Flexible cooperation in European foreign and security policy has risen rapidly up the European agenda because of new challenges to European security, with the loss of the UK, the rise of Donald Trump, and the growing threat posed by Russia. Flexible modes of cooperating in European foreign and security policy remain potentially divisive as they run counter to the formative narrative around EU foreign policy: “to speak with one voice”.

As a response to the prospect of Brexit, and to reiterate their commitment to the EU as a means of strengthening European security, in June and September 2016 France and Germany, at the level of both foreign and defence ministers, pushed jointly for tangible progress on European security and defence.[6] Italy and Spain joined this initiative, expressing their support for these proposals in the autumn of 2016. This was then reflected at EU level in the conclusions of the November 2016 Foreign Affairs Council and the December 2016 European Council, as well as in the European Defence Action Plan in November 2016. The parallel push for real progress in NATO-EU cooperation emanates from Europeans’ new drive to take greater responsibility for security on and around the continent. The co-authored paper by French and German defence ministers also refers refers to the prospect of reactivating the dormant instrument of PESCO.[7]

How do the discussions around PESCO look in European capitals today? In direct relation to PESCO, the results of the research show that three major issues are still live concerns for member states. The first is the need to avoid competition between EU and NATO structures. The second relates to the criteria that member states will have to meet in order to be able to join PESCO. The third is whether the instrument has any added value at all.

As regards the first concern, this is the newest manifestation of the longstanding worry about potential duplication of NATO activities. The research suggested, however, that the latest efforts in EU-NATO cooperation are beginning to pay off. It was felt that the joint push by the High Representative Federica Mogherini and member states to improve EU-NATO cooperation seems, gradually, to be allaying these concerns.

Worries about the inclusiveness – or lack thereof – of PESCO projects continues to be held by many EU countries, especially those that fear they will not meet the criteria of projects and could be left out. The research revealed that a majority of countries (15) hold a view of the instrument that is “overall positive”, while nine member states are undecided, and four have an overall sceptical attitude.

The French were the most forcible in raising the question of why Europeans should employ PESCO at all. They continue to point to other ways to cooperate that are less formalised and can produce results much quicker. For France, European cooperation on foreign, security and defence issues is very high on its priority list, but it believes the options for cooperation on this are already extremely flexible. That being said, some member states think that PESCO could represent the first step towards building the structures for a ʻSchengen of defenceʼ, with a real transfer of sovereignty in the domain of defence and security.

Germany shares the French stance and has beefed up its engagement both in bilateral activities (such as with the Dutch) and in the NATO framework where Berlin initiated the “Framework Nations Concept” in 2013.[8] But, equally, Germany continues to stick to the EU framework, to show that the EU matters on security and defence, and that it has mechanisms in place to include others. This also reflects the traditional comfort Germany finds in the EU’s institutional structures.

Now that it is leaving the EU, the UK does not see PESCO as a priority. Having said that, the findings show that the UK is likely to support measures that strengthen European security and defence cooperation and that might boost European spending on defence. It will, however, oppose anything that duplicates NATO functions or encourages fragmentation in Europe.

In Italy’s view, the aim of PESCO should be to decisively reinforce European defence. But it should be in conformity with the treaties, based on multilevel governance, inclusive for any member state that wants to join, and without a veto option for the partnering countries on specific projects.

Among the smaller members, views were varied. Austria, like Germany, favours an inclusive definition of PESCO that would allow all member states to join projects. It has stated several times that PESCO participation criteria should include not only budgetary figures but also deployment figures. On this gauge, Austria performs better when compared to defence spending as a proportion of GDP. Meanwhile, Bulgaria has been taking part in the development of PESCO and considering different options. It has put forward several ideas that reflect its interests, capabilities and experience, such as contributing to a medical hub and further developing battle groups.

For the Netherlands and Portugal, NATO comes first. Portugal in particular is worried about other countries being left behind. Greece, one of the EU countries with the largest investment in defence as part of GDP, has not joined the discussion on PESCO. Given its economic situation and the refugee crisis, Greece is more interested in monetary and border policies.

Conclusion

The potential offered by greater use of flexible cooperation has clearly recaptured the interest of member states across the EU. This shift, articulated by leaders of core EU member states, and identified by this research, is attributable to the rapid changes taking place inside and around the EU. This is true of foreign and security policy in particular, but it is also true of other high-profile areas, like economic and monetary union and migration management.

Furthermore, a critical mass of countries agree not just on the need for more flexible cooperation, but that flexibility would be most successful were it anchored in the treaties, so as to minimise the risk of placing further strain on the EU. This approach is most likely to find favour with a range of member states of differing sizes and interests: from larger, older members that wish to retain a firm rules-based approach, to smaller members worried about being dominated by one country, or being left out.

Having said that, developments since the conclusion of the research may have altered matters yet again. Countries with a traditionally cautious stance on flexibility outside of the EU framework, most notably Germany, Italy, and Spain, are now more open to exploring it.

But challenges remain across the board. France is keen to move forward with ‘what works’ for the EU as a whole, while countries like Poland and Hungary view flexible approaches less through the lens of strengthening European unity and capacity and more with a view to defending and repatriating national sovereignty.

Nervousness remains among many of the most deeply pro-European countries about the centrifugal risks associated with flexible approaches. This is certainly mirrored in the latest white paper by the European Commission, which is keen to retain the upper hand in the flexibility debate, and keep cooperation within treaty structures.

There is still no consensus about what form flexible cooperation might take. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that the research shows that any proposals that are taken forward under flexible cooperation are yet to be firmed up.

Indeed, one of the most important aspects of this story only emerges when one takes a step back and considers what this tells us about the EU’s evolution and how core member states understand it. It is becoming an organisation whose watchword is increasingly one of ‘cooperation’ and ‘deliverables’ rather than ‘integration’ – despite its foundational goal of ‘ever-closer union’.

Because of this, countries like Spain, Italy, and even Germany have started to overcome their aversion to risk vis-à-vis flexibility, and have joined with France to push for a flexible EU on security and defence matters. However, while European leaders pore over criteria for making PESCO a reality, what is now needed is a small number of flagship European projects that member states can set in train and deliver results through. These could rebuild trust among participating member states – and win back faith in the benefit of collective action.

Annex: PESCO projects: What is on the horizon?

When researchers investigated concrete projects that could be started under PESCO in the coming months, member states provided very few details. By and large, the focus of member state governments is on the precise nature and structure of PESCO activities, rather than the actual issues they could tackle. However, the area under exploration by most member states is crisis management.

Details of nascent projects and preferences for PESCO initiatives are as follows:

- Austria has proposed joint procurement of dual-use capabilities (such as helicopters), the establishment of a civil-military command, and joint training activities. Besides the treaty provision related to PESCO, Austria also favours more permanent cooperation in regional formats, such as Central European Defence Cooperation. Austria’s red line is providing troops in high-tech combat operations.

- Bulgaria would, in theory, support projects in a number of areas (medical hub, logistics/sharing, satellite imagery reading, battlegroups, further development and other regional forms of cooperation). Bulgaria has been contributing medical staff and equipment for operations in Mali and other missions, with medical evacuation from other countries. Logistics and satellite imagery are other areas in which the country wants to participate in the future. The government supports modular cooperation and currently has several projects under consideration, including participating in and further developing battlegroups, i.e. the Balkan Battle Group (HELBROC) of Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, and Cyprus. Sofia has considered joining or leading another battlegroup, and has discussed this with EU partners, but no concrete steps have been taken yet.

- Czechia would be open to participating in coordination of acquisitions, in joint European Defence Agency projects, and joint planning capacities. It would also support the creation of joint headquarters for European defence operations.

- Estonia considers R&D, military operations and missions, civil-military cooperation, crisis management, and terrorism, as areas of potential cooperation.

- Finland has been somewhat frustrated at the slow progress on the EU’s security and defence policy and welcomes the possibility of making more rapid progress. For Finland, areas of particular interest are the coordination of defence planning cycles, security of supply, and defence market policy.

- Germany is mostly concerned with crisis management, even though it considers that defence matters should remain largely with NATO. The co-authored paper by the French and German defence ministers paper examination of: strategic transport capabilities; European logistical hubs; situational awareness; and training.

- Ireland’s policy of neutrality makes it politically sensitive to push for PESCO. Having said that, the Irish government feels there should be a focus on promoting what can be delivered, and then actually delivering on it. There are certainly aspects of PESCO where Ireland would see significant technical and practical advantages – particularly when it comes to an enhanced pooling of resources for key Irish interests such as peacekeeping and crisis management.

- Latvia is interested in: pursuing joint procurements, especially in the military domain; developing informational networks for sharing information regarding cyber security and terrorism; cooperating on law enforcement authorities; strengthening the external and coast borders; and working with third countries on immigration matters.

- Romania is looking at joint acquisition programmes, joint training activities and the provision of maintenance and participation in EU battle groups.

[1] “Discussing EU integration with Alexander Stubb”, Mark Leonard’s World in 30 Minutes, the European Council on Foreign Relations, 16 February 2017, available at https://ecfr.eu/podcasts/episode/the_world_in_30_minutes_discussing_eu_integration_with_alexander_stubb.

[2] Patrick Wintour, “Plans for two-speed Europe risk split with ʻperipheralʼ members”, the Guardian, 14 February 2017, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/14/plans-for-two-speed-eu-risk-split-with-peripheral-members.

[3] “Commission presents White Paper on the future of Europe: Avenues for unity for the EU at 27”, European Commission, 1 March 2017, available at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-385_en.htm.

[4] Jo Coelmont, “Permanent Sovereign COoperation (PESCO) to Underpin the EU Global Strategy”, Egmont Royal Institute for International Relations, December 2016, available at http://www.egmontinstitute.be/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/SPB80.pdf; and Frédéric Mauro, “Permanent Structured Cooperation: The Sleeping Beauty of European Defence”, Groupe de recherche et d’information sur la paix et la sécurité, 27 May 2015, available at http://www.grip.org/sites/grip.org/files/NOTES_ANALYSE/2015/NA_2015-05-27_EN_F-MAURO.pdf.

[5] “Benelux vision on the future of Europe”, website of Charles Michel, Prime Minister of Belgium, 3 February 2017, available at http://premier.fgov.be/en/benelux-vision-future-europe.

[6] Jean-Marc Ayrault and Frank-Walter Steinmeier “A strong Europe in a world of uncertainties”, Auswärtiges Amt, June 2016, available at http://www.voltairenet.org/IMG/pdf/DokumentUE-2.pdf; and, Ursula von der Leyen and Jean-Yves Le Drian, “Erneuerung der GSVP: Hin zu einer umfassenden, glaubwürdigen und realistischen Verteidigung in der EU”, Bundesministerium der Verteidigung, September 2016, available at http://bit.ly/2cBvieX.

[7] Sven Biscop, “Oratio Pro PESCO”, Egmont Royal Institute of International Affairs, January 2017, available at http://www.egmontinstitute.be/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ep91.pdf.

[8] Claudia Major and Christian Mölling, “The Framework Nations Concept: Germany’s Contribution to a Capable European Defence”, SWP Comments, December 2014, available at https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/comments/2014C52_mjr_mlg.pdf.

Analysis by country

Austria

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

Austria is a small, strongly export-oriented country and its immediate neighbours are its most important trading partners. Thus, the European internal market and the ‘four freedoms’ are of crucial importance to its economy.

Prior to joining the European Union, integration was viewed as an instrument for redefining Austrian foreign policy. During the cold war, Austria was neutral between east and west. It has sought to use EU membership to more firmly anchor Austrian foreign policy in the West, while still retaining its formal neutrality. According to a survey conducted by the Austrian Society for European Politics, 61 percent of Austrians believe that their country should remain a member of the EU, as opposed to 23 percent that would favour leaving.

Overall, Austria’s integration into the EU has also led to higher economic growth and greater prosperity. European integration has contributed to around 0.5 percent to

1 percent of the country’s annual GDP growth. However, Austria has been a ‘policy taker’ rather than a ‘policy maker’. It has attempted to be an active participant in foreign policy using its special status as a neutral country.

Views on flexible cooperation

Overall, Austria favours a common approach to further integration. In areas where no agreement can be reached, Austria would opt for flexible integration. It would consider supporting a less rigid institutional and legal EU framework.

Austria’s preference for ‘flexible union’ includes cooperation initiatives outside of the EU treaties that could later be transferred into them, as Schengen was. Austria sees this as an opportunity to overcome deadlocks and strengthen national sovereignty on core policies. However, Austrians remain concerned at the prospect of hollowing out the EU framework and the potential dominance of larger countries within a ‘flexible union’.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

Austria would be open to flexible cooperation on: crisis management; humanitarian missions; and border security and border management. Austria’s preferences betray its views on Europe’s inefficiency in responding to the ongoing migrant crisis. In general, Austria favours an inclusive definition of permanent structured cooperation (PESCO) and is therefore in favour of allowing everyone to join.

Belgium

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

Belgium continues to strongly support deeper integration. Its positive stance towards the European institutions and the ‘community method’ is reflected in both the political class and – to some extent – within public opinion. Nonetheless, Belgium is aware that this position is no longer sustainable among the majority of member states. The Netherlands, one of Belgium’s closest partners, and previously supportive of this view, no longer supports it. Consequently, Belgium now prioritises the preservation of the European Union’s existing accomplishments over a deepening of its capacities on new issues.

Belgium depends heavily on agreements with neighbouring member states for its security. For example, on terrorism prevention, Belgium’s primary partners are France and Germany. As well as external border security, Belgium strongly supports a common EU approach, precisely because it recognises its own inability to act alone effectively.

Views on flexible cooperation

Belgium believes that, given the current situation, the benefits of flexible cooperation outweigh the risks. It views ‘flexible union’ as an opportunity to demonstrate the benefits of collective action and overcome deadlocks in some important policy areas. Belgium continues to place emphasis on the importance of regaining trust in the EU and its institutions.

Belgium’s preference for flexible integration would be to make use of existing instruments provided in the EU treaties (enhanced cooperation, permanent structured cooperation) rather than more informal mechanisms.

However, Belgium does remain cautious. Its concerns include: the marginalisation of EU institutions, a fear of returning responsibilities back to member states, and the dominance of larger countries with better resources.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

Belgium would be open to flexible cooperation on: crisis management; stabilisation, nation-building and development policies (for example, for Syria and Iraq); humanitarian missions; cooperation and integration in defence; joint capacities for emergency planning in crisis scenarios; border security and border management; and migration and asylum.

Bulgaria

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

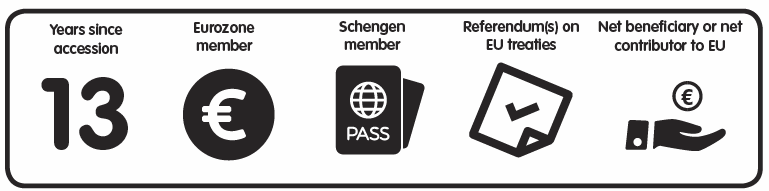

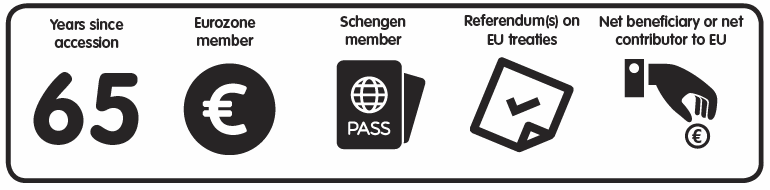

It has been ten years since Bulgaria joined the European Union. Over that time, it has remained pro-integration, both in public opinion and governmental outlook. However, recent polling shows that support for EU membership has declined from nearly 70 percent in 2013 to 57 percent in 2016.

Bulgaria joined the EU amid expectations of better governance and further economic prosperity – a narrative that can be characterised as the ‘return to Europe’. In this respect, Bulgaria’s membership was understood as both the fulfilment of a national strategy and a tactical effort to improve its economy.

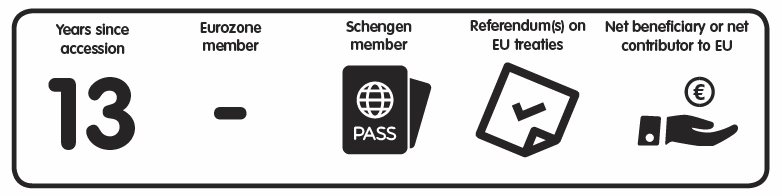

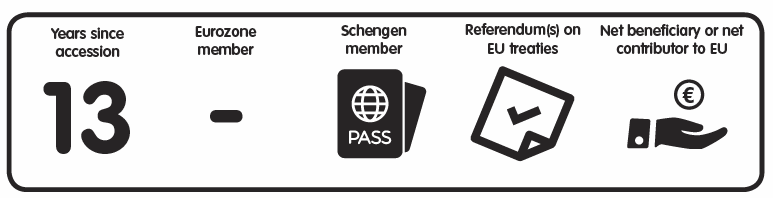

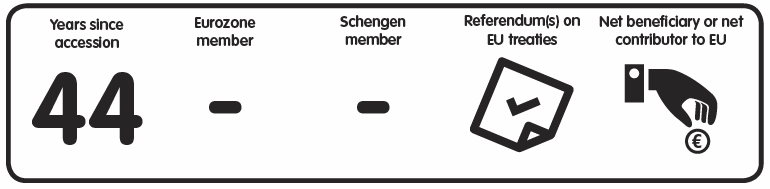

In regard to policy formation, Bulgaria is considered to be a ‘policy taker’ rather than a ‘policy maker’. Bulgaria’s focus remains on energy, the single market, and the enlargement and neighbourhood policy. Germany often emerges as the primary ‘policy maker’ in many of these areas, with the United Kingdom also pushing developments in the single market and the enlargement agenda. Bulgaria has not joined Schengen or the eurozone, but retains its ambition to do so.

Views on flexible cooperation

There is some apprehension in Bulgaria about the potential for the EU to divide into ‘core’ and ‘periphery’. Bulgaria fears being left on the periphery with limited or no ability to shape policies. This is related to the fear of the eurozone becoming the new vehicle for integration. Bulgaria wishes to avoid a two-tier system, which it believes could lead to the domination of the larger eurozone economies.

However, Bulgaria genuinely views flexible cooperation as beneficial, if not necessary, in different policy areas, and something that will strengthen overall European collaboration. But it is concerned that there are serious risks of centrifugal tendencies, including the marginalisation of EU institutions and the hollowing out of the EU framework at large.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

Overall, Bulgaria’s preferred areas for flexible cooperation include: crisis management; stabilisation, nation-building and development policies; humanitarian missions; cooperation and integration in defence; joint capacities for emergency planning in acute crisis scenarios; border security and border management; and migration and asylum policy.

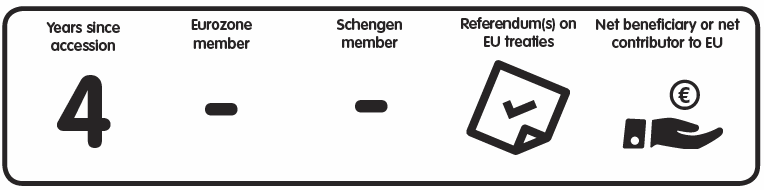

Croatia

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

Between 2007 and 2014, Croatia’s outlook on European Union membership was predominantly positive. The political elite promoted accession as a means of strengthening the rule of law, expanding markets, boosting the economy, and fostering investments. The intense political and media campaign to promote accession was reflected in positive public opinion on joining the EU.

Croatia became a full member state in July 2013. However, the beginning of Croatia’s EU membership was marked by controversy, when the government attempted to renege on its pre-accession commitments. In September 2013, the European Commission threatened Croatia with sanctions after the government refused to remove its limit on the application of the European arrest warrant for crimes committed after August 2002. However, the conflict ended after the government agreed to fulfil its pre-accession obligations.

Views on flexible cooperation

There has been little talk about flexible cooperation in Croatia and the new administration has positioned itself as overwhelmingly pro-European. Croatia is likely to take a positive stance towards cooperation based on instruments provided in the EU treaties, such as enhanced cooperation and permanent structured cooperation (PESCO). But it will want that cooperation to demonstrate the benefits of collective European action as a means of regaining public trust in the EU. In January, the prime minster, Andrej Plenković, said that Croatia believes that the EU has to be ready to use all of the instruments at its disposal to combat the series of crises that have assailed it.

Broadly speaking, there is a consensus in Croatia that the EU has to adapt to changing circumstances. In that regard, new methods of cooperation are seen as a necessity. However, Croatia remains cautious about the marginalisation of EU institutions, and the hollowing out of the EU framework.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

Croatia’s overall attitude towards PESCO is positive. Croatia appears to welcome the readiness of member states to discuss the model and the opportunities it presents. PESCO is considered to be something of particular interest for smaller EU member states, which lack the capacity to act comprehensively at the EU level. Additionally, there is some concern that the chasm in capabilities between member states could hinder cooperation.

Cyprus

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

Since Cyprus’s accession to the European Union, Cypriots have overall remained positive about European integration. EU membership has also reinforced Cyprus’s status as a sovereign country. Even during the financial crisis in 2012-13, when Cyprus had to implement very tough bailout conditions, support for the EU did not diminish as it did in Greece.

Over the years, Cyprus’s various governments have all placed a strong emphasis on the importance of EU membership, as well as on constructively contributing to EU policy formation. As an example, Cyprus acquiesced on EU sanctions against Russia, despite the adverse effect it had on the Cypriot economy.

During the pre-accession period, the foreign policy objectives of Cyprus did not stretch beyond its periphery. But now, as part of the political and economic union, it has begun to engage further afield.

Views on flexible cooperation

Cyprus is invested in the EU as a ‘homogeneous union’, whose core decisions and policies are implemented universally. Therefore, Cyprus believes that a ‘multi-speed union’ would harm the integrity of the EU.

Cyprus believes that a ‘multi-speed’ Europe would enable certain member states to avoid fulfilling certain policy objectives, and would encourage the exclusion of some member states by others. Cypriot policymakers and bureaucrats consider this a threat that could lead to further disintegration of the EU, particularly given the United Kingdom’s decision to leave.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

The Cypriot government has not explored any concrete projects as part of permanent structured cooperation. Cyprus would nevertheless support investments and ‘capability cooperation’, which in its view should ensure that all member states are included, and in which the eventual aim would be greater strategic autonomy for the EU.

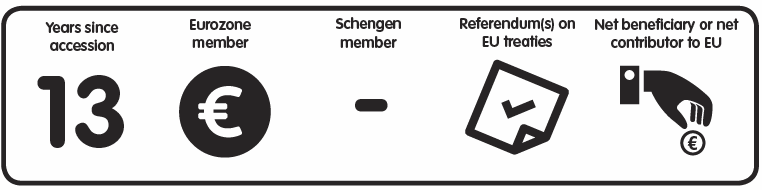

Czech Republic

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

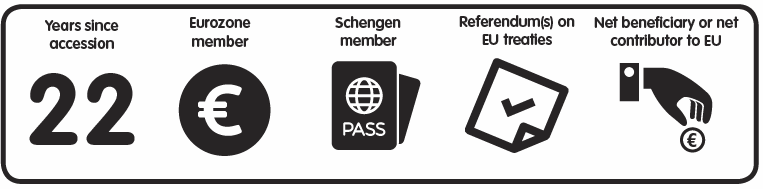

From the standpoint of the country’s political elite, the Czech Republic’s accession to the European Union represented the completion of the political, economic and social transition of the country.

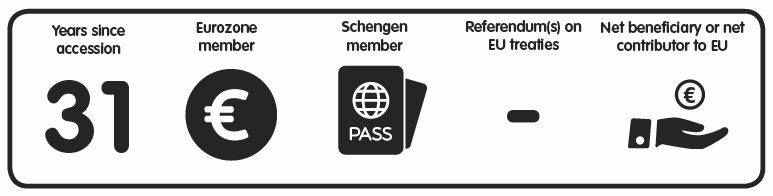

Between 2004 and 2009, there was a period of relatively strong consensus on EU membership, characterised by an attempt to become a fully fledged member (to include entering the Schengen zone, and adopting the euro) as quickly as possible. The support for EU membership among the citizenry was very high – peaking during the Czech presidency of the EU in the first half of 2009.

Between 2009 and 2013, however, the political elite became extremely polarised in their views on EU membership. The then government gradually changed the country’s trajectory on EU integration (for example, abandoning the policy of adopting of the euro, and initially refusing to sign the up to the Fiscal Stability Treaty). The Czech Republic has now acquired the image of a ‘troublemaker’ within the EU. Over the same period, support for the EU membership sharply declined in opinion polls.

Since 2013, a ‘pro-European’ government has begun changing the political discourse yet again, promoting the idea that the strategic priority of the country lies in being at the centre of European integration. There has been a slow growth in support for EU membership among citizens.

Views on flexible cooperation

The Czech position on flexible cooperation has evolved from flatout rejection to cold acceptance. Nowadays, the country acknowledges that flexible cooperation might be beneficial for European cooperation if based on instruments provided in the EU treaties, with the full involvement of EU institutions, inclusive and used as a last resort.

The Czech Republic sees flexible cooperation as a means to demonstrate the benefits of collective European action and restore trust in the EU, allow for a less rigid institutional and legal EU framework, and overcome deadlocks in relevant policies. However, it remains concerned by the potential marginalisation of EU institutions and the dominance of larger countries with better resources.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

The Czech Republic strongly supports closer defence cooperation, believing in the establishment of a new security and defence union. The Czech Republic believes that recent trends in geopolitics and security show that a focus on external security issues and defence policy has become a strategic necessity for the EU and its member states.

The Czech Republic is interested in joining different projects within permanent structured cooperation (PESCO). It holds that future cooperation should be taken forward by all member states when possible. But overall, PESCO is viewed as an instrument for the strengthening of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) and European defence capacities at a moment when not all EU member states agree on defence as a priority. Therefore, Czech support for PESCO is in line with its general support for a stronger CSDP as envisaged in the European Security Strategy.

Outside of defence, the Czech Republic would also support flexible cooperation in the areas of: crisis management; stabilisation, nation-building and development policies (for example, for Syria and Iraq); humanitarian missions; cooperation and integration in defence; joint capacities for emergency planning in acute crisis scenarios in member states; and border security and border management.

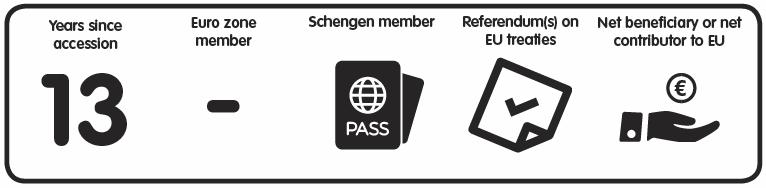

Denmark

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

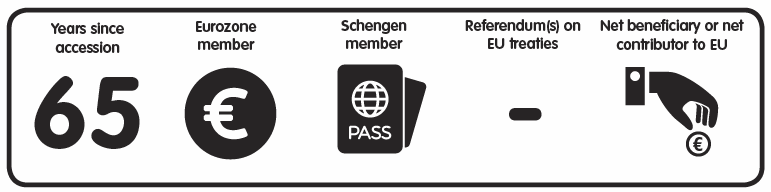

Denmark joined the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973, alongside Ireland and the United Kingdom. One of the common rationales behind membership was that both Denmark and Ireland had a high degree of economic linkage to the UK, and so both countries found it necessary to join the EEC if the UK did.

Denmark, however, has always had an ambivalent relationship with European integration. It has negotiated four opt-outs in its European Union membership since 1993 on: security and defence; citizenship; police and justice; and the adoption of the euro. All of this was necessary to secure the passing of the Maastricht Treaty in a referendum.

Since 1993, two Danish governments have held referendums on modifying these opt-outs. The first took place in 2000, rejecting the adoption of the euro by 53.2 percent to 46.8 percent on a turnout of 87.6 percent. Second, in 2015, it rejected a bid to convert its full opt-out on justice and home affairs matters into a case-by-case opt-out, similar to that currently held by Ireland and the UK. The amendment was rejected by 53.1 percent to 46.9 percent on a turnout of 72 percent.

Following the UK’s decision to leave the EU, Danish voters showed increased support for remaining in the EU. This is a significant development since several Danish political parties and the electorate in general have long promoted Euroscepticism. Denmark has several major Eurosceptic parties, including the Red-Green Alliance and the Danish People’s Party. However, a Voxmeter poll from July 2016 shows a total of 69 percent of Danish voters now endorsing the country’s membership of the EU. This is a 10 percent increase – up from the level of support prior to the Brexit vote.

Views on flexible cooperation

Denmark is worried that ‘flexible union’ would push the EU in different directions, at a time when Europe already lacks cohesion following the Brexit vote and the 2008 financial crisis. Denmark therefore finds it very difficult to advocate for a more specialised and flexible union. It believes that an EU that moves in many different directions would ultimately become weak.

From the Danish perspective, the linkages between the issues of external border security, the fight against terrorism, and immigration and asylum policies, mean that member states have a shared interest in working together. Yet they feel that many countries use EU forums on these issues to trash the fundamental elements of the EU’s political culture, often in order to promote specific national goals. As a result, Denmark feels that ‘collective action’ is actually undermining the ‘collective’ itself.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

Due to its EU opt-outs, Denmark is unable to participate in EU military operations or in cooperation on development and acquisition of military capabilities within the EU framework. Nor will Denmark participate in any decisions or planning in this regard. However, Denmark could be open to flexible cooperation on migration and asylum policy.

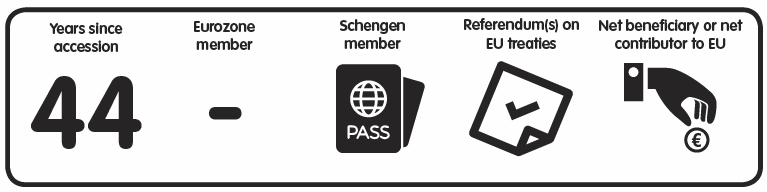

Estonia

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

Estonia’s membership of the European Union was originally conceived for a very clear and instrumentalist reason: to fully secure Estonia’s independence. But, over time, Estonia has become more engaged on the ideological questions of European integration. As a small post-communist member state, its natural position is one of a ‘policy taker’, but the ideological turn has brought about the possibility and the desire to more consciously shape policy.

Estonia has one of the smallest public budget deficits and sovereign debt levels among EU states. It now champions the idea that other member states should appreciate and embrace similar policies. While many Estonians question the role of austerity in re-establishing growth, the general view among the political elite, civil servants and public opinion, is one of strong support for its hawkish fiscal position. Estonia has also been a strong supporter Germany’s leadership in advocating austerity.

Views on flexible cooperation

Estonia’s stance is that cohesion of the EU is more important than negotiated outcomes based on single issues. It believes there is a need, and indeed a readiness, to make compromises in order to protect European unity.

Estonia’s preferred modus operandi is to cooperate outside of the EU treaties and advocate for a Schengen-style transfer of initiatives into the treaties at a later stage. Estonia is cautious of the dominance of Germany within a more ‘flexible union’.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

There is a consensus among Estonian officials that the EU needs to revise its security policy in light of the radical changes that have taken place in Europe in recent years. Thus, for example, the Implementation Plan on Security and Defence, introduced by High Representative Federica Mogherini in November 2016, was seen as positive and necessary step towards strengthening security and defence cooperation inside the EU. After the election of Donald Trump and the consequent worries of abandonment by the United States, Estonia is even readier to contribute to EU initiatives in order to hedge its bets on security policy.

Finland

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

Finland’s current government believes that ‘[t]he most important task of the European Union is to safeguard peace, security, prosperity, and the rule of law on our continent’. This reflects the long-standing Finnish outlook on EU membership: that it serves to enhance Finland’s security and prosperity and to provide it with a level of influence that would be unattainable for a small state outside the EU. In addition to the benefits it receives in terms of security, prosperity, and influence, successive Finnish governments have placed significant emphasis on the EU’S ability to anchor Finland in a European family of values.

Throughout most of its time as a member, Finnish EU policy has been based on the idea that Finland has to be a pragmatic and results-orientated member state that is part of the solution rather than part of the problem. As a small member state, Finland has tried to influence EU policies as early as possible, for example by shaping agenda points and working together with the European Commission and other relevant actors. In the decision-making phase, Finland has traditionally presented itself as a pragmatic and flexible negotiator, or even mediator, rather than as a tough player.

With regard to public opinion, the crises of recent years seem to have had little impact on Finns’ views of EU membership. According to the Finnish Business and Policy Forum’s annual poll, at the end of 2016, 46 percent of respondents held a positive view of Finland’s EU membership, with 32 percent saying they had a neutral view. Only 20 percent said that their view of Finland’s EU membership was negative.

Views on flexible cooperation

Finland values the EU’s institutional and legal framework as well as common rules, which guarantee that all member states, regardless of their size, have similar rights and obligations. Traditionally Finland has therefore been rather sceptical of any form of flexible cooperation, especially if such cooperation takes place outside, or on the margins, of the EU’s legal and institutional order. Finland has also placed significant emphasis on unity and on avoiding dividing lines within the EU, not least because its Nordic partners, Sweden and Denmark, are both outside the eurozone. Finland has stressed unity as a central objective now that the EU has to deal with the Brexit process. Again, this has translated into a rather cautious view of flexible forms of cooperation.

At the same time, recent Finnish governments have emphasised that the EU has to become more effective and deliver results in order to win back the trust of its citizens and overcome the many crises weakening it. In this context, Finland sees that some form of enhanced or flexible cooperation within the confines of the treaties might be necessary. However, such cooperation would have to be as open and inclusive as possible in order not to create dividing lines.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

The EU’s security and defence policy has long been an area of particular importance for Finland. The Ukraine crisis and the tensions between the EU and Russia have recently underlined the importance of the EU in terms of security, meaning that the development of the EU’s security and defence is a clear priority of the current government. Permanent structured cooperation fits Finland’s requirements for flexible cooperation, as it is based on existing treaty provisions. Finland has also been somewhat frustrated at the slow progress in the EU’s security and defence policy and welcomes the possibility of achieving more rapid progress.

France

Go back to the list of member states

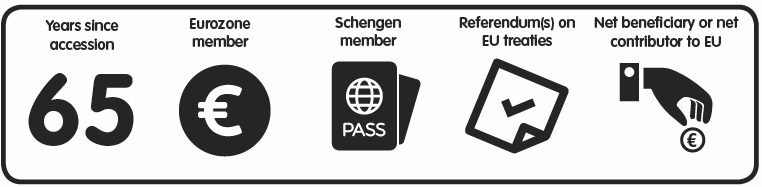

Attitude towards the European Union

French leaders have always aimed to be ‘policy makers’ in the European project rather than embracing a purely transactional and interest-based approach.

The ‘No’ vote in the referendum on the European constitution in 2005 marked the end of openly federalist discourse in France. The European Union became an increasingly toxic topic for French politicians, and the vote in favour of the Lisbon Treaty by the National Assembly two years later did not help rebuild a consensus. According to a Gallup poll from December 2016, 32 percent of the French population would like to exit the EU.

The French vision was always built on a strong Franco-German partnership, described as the engine of the European project. This has been challenged in recent years, either by lack of investment in the relationship with Germany, or by the new European balance of power following the enlargement to the east and French economic stagnation. If the importance of France remains particularly evident in the area of foreign and defence policy, on economic, institutional and political issues, the gap with Germany has widened significantly. Despite regular initiatives to revive a joint vision for the

EU – for instance, the joint letter of Jean-Marc Ayrault and Frank-Walter Steinmeier for a ‘strong Europe in a world of uncertainties’ after the Brexit vote – the partnership remains unbalanced.

Views on flexible cooperation

François Hollande has consistently supported a more flexible EU, but has been reluctant to push an ambitious agenda of institutional reform before the French presidential election. His position on this did change in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote. During that period he came to accept Angela Merkel’s view that the British referendum had created a new context, one in which preserving EU unity among the EU27 would be key for the future of Europe. The debate since the Brexit vote has seen a greater openness – if only tactical – from Germany towards flexibility. This was seen at the Versailles mini-summit held in March 2017 where France, Germany, Italy, and Spain supported the notion that some countries should be able to move further and faster in some key areas. The French approach could change yet again depending on the result of the presidential elections.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

Officially, the government is open to the idea of permanent structured cooperation (PESCO). In practice, French officials are divided. They think PESCO could be a first step in building the structures for a ‘Schengen of defence’, with a real transfer of sovereignty in the domain of defence and security. Theoretically, it could also be a way to overcome blockages by one country, or a group of countries, and find operational solutions. However, there are worries in the French government that the current plans for PESCO may be too bureaucratically onerous, confusing to the public, and risky for European unity. PESCO permits only one group of countries to be formed under it; a second, with different rules, is not permitted. The fact that there can only be one is a major constraint to its use. PESCO is therefore seen in France as a last option, only to be used in the event of a total blockage.

Germany

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

Germany has benefited greatly from European Union membership and over the decades has emerged as a leading country in shaping EU structures and policies. In doing so, Germany has contributed to shaping a union that matches its core interests. EU membership approval rates are strong in the country, and the federal government’s commitment to the EU has remained robust. Germany continues to see the EU as the main umbrella for European cooperation, but in recent years it has failed to gain sufficient support from its EU partners regarding core policies such as the future governance of the eurozone, and the response to the refugee crisis. The German federal government has consistently emphasised the importance of the EU in security and defence and the strong role it should play in this area. It continues to make efforts to step up its role in NATO and sees EU security and defence efforts in a role complementary to, not replacing, NATO.

Views on flexible cooperation

The German government has a strong interest in demonstrating the benefits of addressing challenges collectively within the EU framework. Its motivation is to prevent further disintegration by demonstrating successes from collective action. Until recently the German government was hesitant about exploring flexible modes of cooperation due to the fear of undermining unity and the potential development of an even more complex legal and political environment, which would outweigh the benefits of flexibility. However, the weakness of the EU has made the German government open to exploring flexible types of cooperation. In the current environment, it is examining the benefits of flexible cooperation as a means to strengthen European collaboration. There is a wide range of views about the different types and modes of flexible cooperation, including cooperation based on instruments provided in the treaties as well as cooperation outside the treaties. Overall there is a readiness to explore new options in order to prevent the EU from breaking up.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

Germany thinks that the strengthening of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) sends an important political message, demonstrating the relevance and competence of the EU in security matters. Against that background, Berlin has pushed for permanent structured cooperation (PESCO) to be put back onto the EU’s agenda. At the same time, Germany is decisively stepping up its role in NATO, and is further exploring bilateral initiatives.

Greece

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

In recent times Greece has tended to approach the European Union in an inward-looking way. As the only eurozone country under supervision by the International Monetary Fund, it associates the role of the EU with the conclusion of bailout reviews. Apart from the refugee crisis, no other issues of European interest are discussed much in politics and the media. The image of the EU has been generally tainted in recent years due to the economic crisis. It has been accused by politicians and the media of being responsible for the Greek drama and its continuation. But the governing party, Syriza, goes even further, and some of its members of parliament believe that a debate should be launched about whether Greece should remain in the eurozone or return to the drachma currency. A recent survey conducted by polling company Alco in Greece showed that 53 percent of respondents thought joining the eurozone was the wrong decision, while only 38 percent supported the decision.

The Greek government and Syriza members tend to prefer discussing the conclusion of the bailout reviews with the European Commission rather than with the IMF, German politicians, and the president of the Eurogroup, Jeroen Dijsselbloem. On the whole, they portray the European Commission as an actor that attempts to bridge differences among eurozone members and keep Greece in the eurozone.

The main opposition party in Greece, New Democracy, is expected to win the next election, whether this takes place, as scheduled, in September 2019 or earlier. This could lead to better cooperation between the Greek government and the EU, although New Democracy had failed in the past to assume full ownership of necessary reforms. Nevertheless, Euroscepticism will still define the debate because the financial problems affecting Greek society will not be resolved in the foreseeable future.

Views on flexible cooperation

Greece does not take part in the debate on flexible cooperation. In theory the Greek government sees Europe as a promoter of growth and ‘creative flexibility’ in economic affairs. Its main priority is the conclusion of the second review of the third Greek bailout and its main concern is that initiatives leading to a flexible Europe might leave Greece behind, especially if the country fails to apply bailout terms and re-access international markets. Furthermore, throughout the migration crisis, with several member states closing their borders instead of accepting refugees, Greece has strongly disagreed with so-called ‘flexible solidarity’ within the EU. It prefers any flexible cooperation to be based on instruments provided in the EU treaties, and is worried about the status of EU institutions and the EU framework, as well as the dominance of larger countries; especially Germany.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

The Greek government has not actively joined any debate on specific areas for flexible cooperation on defence. It prefers to make vague references to EU foreign policy to express support for the rule of law and the maintenance of regional stability.

Hungary

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

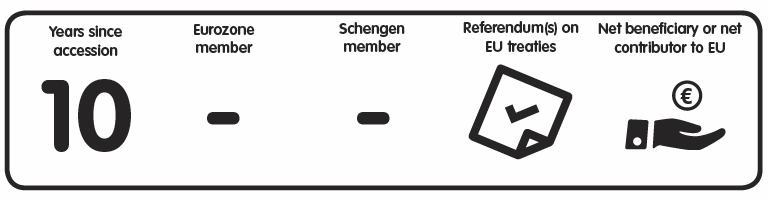

European Union membership was an uncontested foreign policy aim after the regime change in 1989, and Hungary’s ‘return to Europe’ was supported across the political spectrum. Hungarians had high expectations for economic and social transformation following Hungary’s eventual accession in 2004. This then led to disappointment as membership failed to deliver quick results. The financial and economic crisis hit Hungary hard, and the EU’s inability to quickly and effectively address this challenge eventually became a foundational theme of the Viktor Orbán government’s approach to Brussels after taking power in 2010.

Hungary joined the EU as a ‘policy taker’, although in certain policy areas it has clear preferences. In addition to the single market and upholding the four freedoms and Schengen, cohesion and common agricultural policy are of high importance. Joining the monetary union is still not a priority for the current government. Hungary has been a lasting proponent of EU enlargement to the western Balkans, supports Turkey’s EU accession, and is in favour of deepening ties in the eastern neighbourhood, including visa liberalisation. Under the Orbán government, and more precisely during the refugee and migration crisis in 2015, Hungary sought to embrace the role of ‘policy maker’, which led to serious confrontations – and to the emergence of the Visegrád group.

Following on from generally pro-European governments, the Orbán government made a clear Eurosceptic turn with its declared Eastern Opening policy and regular confrontations with the European Commission over the state of democracy and civic rights in the country. After almost seven years of conflict, which have, however, never led to the launch of Article 7 procedures, the Orbán government views Hungary’s EU membership in a transactional manner. It seeks to reap all the benefits while objecting to greater pooling of its sovereignty in the EU.

Views on flexible cooperation

The Orbán government’s primary goal within the EU is to increase and strengthen Hungary’s role and competitiveness, and to this end it examines the benefits derived from current cooperation formats on a case-by-case basis. It then either seeks modifications to the existing policy, or tries to use the available tools to pursue Hungary’s interests. Flexible forms of cooperation can support this overall opportunistic and pragmatic aim, and thus Hungary looks on them positively.

Hungary opposes any form of flexible cooperation that could institutionalise dividing lines in the EU, and exclude member states. For example, a two-speed Europe could contain within it the risk that the interests of big and more resource-rich member states become dominant. Hungary fears that these processes would eventually hollow out the EU framework, and could lead to the country drifting into the periphery.

Preferred areas for flexible cooperation on defence, and other areas if applicable

Hungary is open to flexible cooperation on: crisis management; stabilisation, nation-building and development policies; humanitarian missions; border security and border management; and migration and asylum policy.

Orbán has expressed his support for strengthening security and defence cooperation, but further details about Hungary’s position are unknown. The government is open to further discussion about permanent structured cooperation, but is uncertain about its position within these talks. Hungary could support a framework that is inclusive, simple and effective, but it does not wish to impose more bureaucracy on member states.

Ireland

Go back to the list of member states

Attitude towards the European Union

Ireland retains a positive view of European Union membership that is based on pragmatic rather than ideological engagement. Through its EU membership, Ireland’s economy has been bolstered and its political voice and influence have increased to a level proportionally greater than the country’s small size. Ireland’s positive EU trajectory is reflected in public and political opinions, and it is widely agreed that EU membership has been positive for Ireland politically and economically. It appears that this positive attitude has not changed since the Brexit vote, and the government of Ireland continues to perceive the EU as the main driving force for its future in economic and trade relations.

Ireland would like to see increased integration of economic and monetary union in order to ensure future stability of the eurozone. It is concerned about new barriers and the loss of free trade with the UK after Brexit and it aspires to remain at, or near, the core of EU policymaking, hoping to build new alliances with member states after the UK has exited the EU. Ireland considers the focus areas for cooperation to be: economics and trade; monetary policy; counter-terrorism; human rights; promotion of democracy; and energy security.

Views on flexible cooperation