The transatlantic meaning of Donald Trump: a US-EU Power Audit

Summary

- New ECFR research into how Europeans have adapted to the new US administration reveals three ‘Trump effects’: the Regency Effect, the Messiah Effect, and the Antichrist Effect.

- The Regency Effect dominates. European leaders have largely decided to hope the ‘regents’ around Donald Trump will ensure the familiar transatlantic relationship continues more or less in its current form.

- Other politicians see in Trump a ‘Messiah’ or ‘Antichrist’ figure. For one camp he is a leader set on restoring Western conservative, Christian values; for the other he is a figure to oppose and rally against.

- But Trump is a symptom of the rot in the transatlantic relationship, not the cause. Even before Trump, America was growing more self-interested and distant. Europeans could defend themselves, but they continue to look to America for security because they cannot resolve their own internal disputes.

- A ‘post-American politics’ in Europe is possible and even necessary, but will only come about if EU member states recognise the need. Germany is central to this but its ‘regency’ instincts run deep and it lacks support from other member states.

Introduction

Donald Trump is not shy about self-promotion. So it shocked no one when he shoved aside Duško Marković, the prime minister of tiny Montenegro, to get to the front of the official photograph at the May 2017 NATO summit. It was perhaps more surprising that Marković used the attention generated to “thank President Trump personally for his support” of Montenegro’s entry into NATO, noting “it is natural for the president of the United States to be in the first row.”[1] Power has not been on more conspicuous display since Harry Whittington, the 78-year-old man whom Vice-President Dick Cheney shot in the face in 2006, apologised “for all that [Cheney] and his family have had to go through.”[2]

While Marković’s manhandling and his response is an unusually naked example, it nonetheless neatly encapsulates the nature of the transatlantic relationship. One side pushes and the other asserts that it wanted to be pushed all along.

On the surface, there is no reason for this to be the case. Clearly, in both Europe and America, the election of Trump as president of the United States came as a shock. When we at the European Council on Foreign Relations surveyed viewpoints in the 28 member states of the European Union before the American election, only a couple of opposition parties expected Trump to win. Around Europe, governments saw a win for Hillary Clinton as nearly certain.[3]

But the reaction has been completely different on the two sides of the Atlantic. The US is strongly divided on Trump and his administration, along familiar and roughly partisan lines. He has ignited fierce policy battles in Congress, within his own administration, and even on the streets of the normally placid Charlottesville, Virginia.

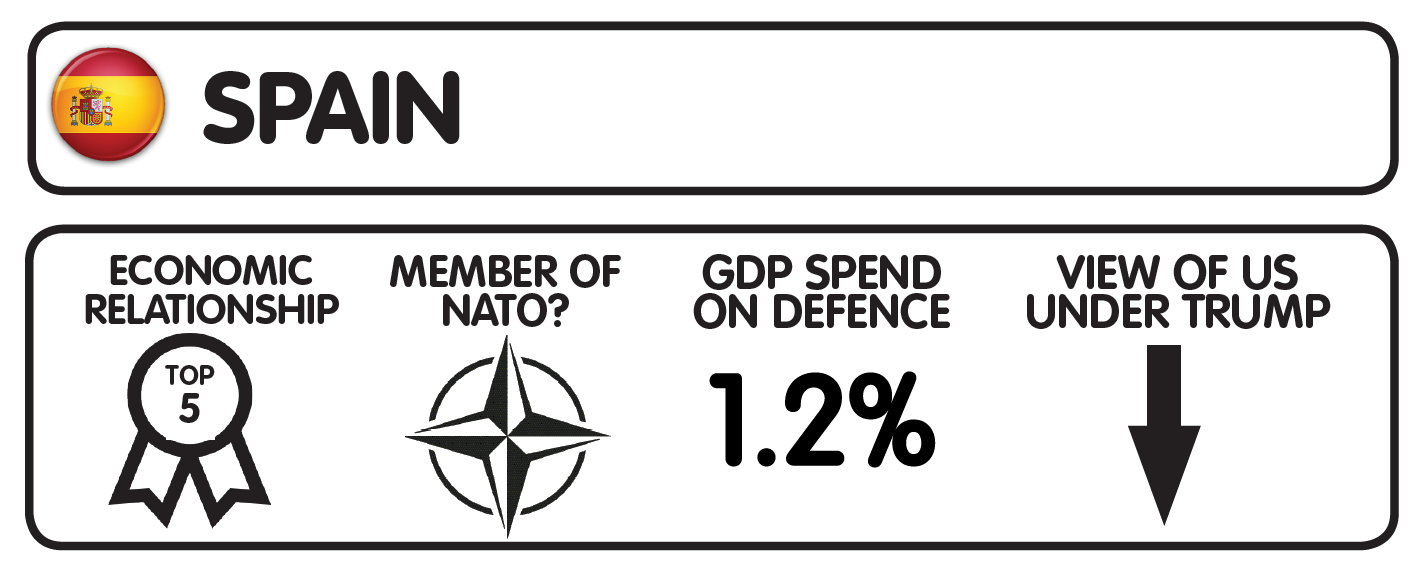

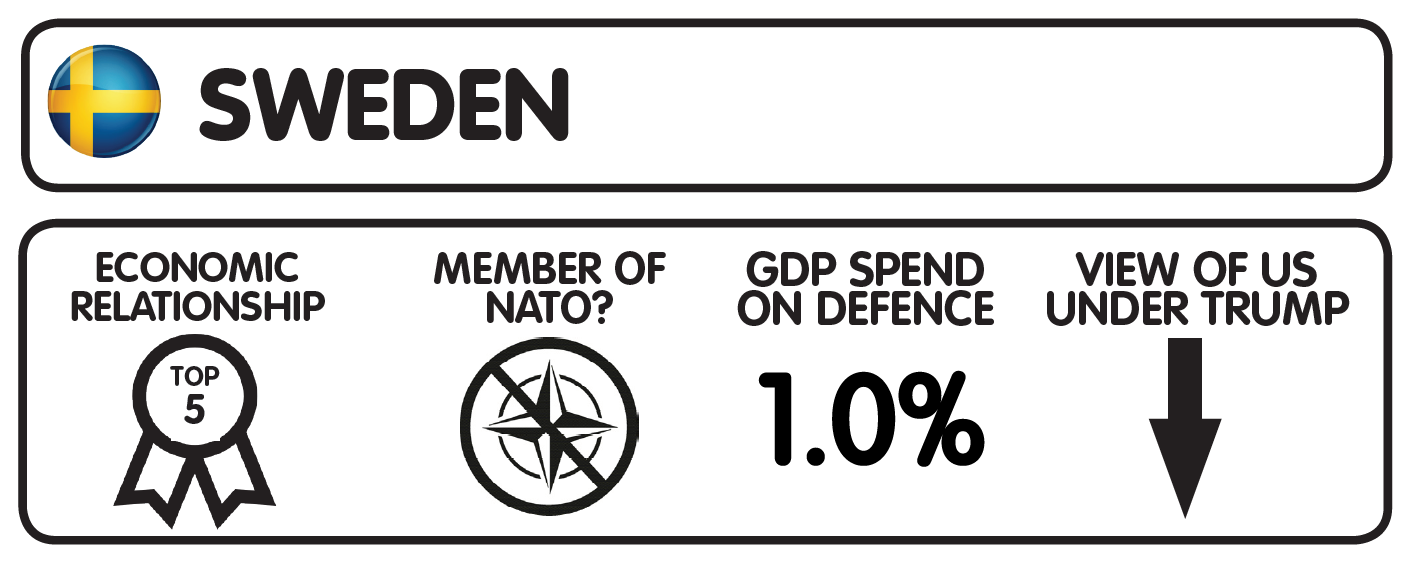

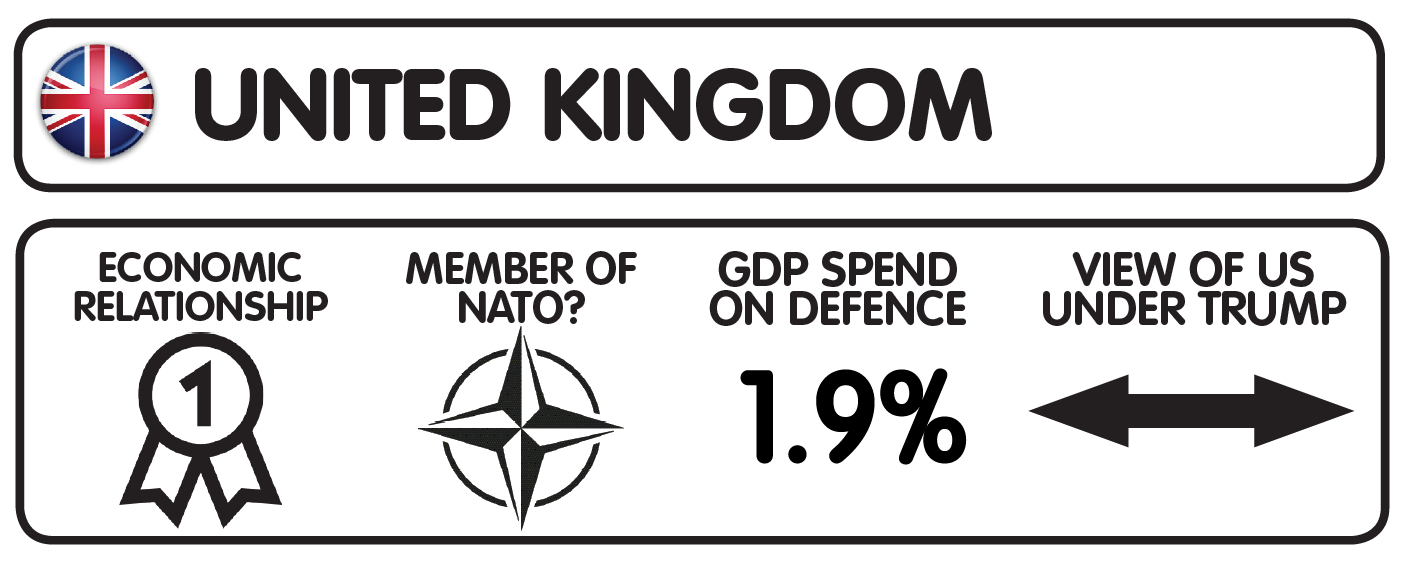

In Europe, there is a much greater consensus on Trump – with some important exceptions, he is very broadly unpopular, among both governments and the European population. In countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and France, the percentage of the population that has confidence in the US president to do the right thing has plummeted more than 50 points since Trump took office. Recent polls demonstrate that he is less popular in Europe than the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, a man who sporadically invades European countries.[4]

Trump’s unpopularity in Europe reflects the fact that he is a very different American president to those that preceded him. He brings to the post not only a harsher tone, but a radically different ideology and a promise to upend decades of US foreign policy practice. His promise to put “America First” represents a fundamental challenge to the idea of the transatlantic relationship and the security of Europe. His appeal to racial intolerance and his stance on climate change represents an affront to European values. His antipathy towards European integration and his intention of rewriting the rules of international trade represent a threat to European prosperity.

Yet, despite this relative consensus on Trump, Europe’s reaction overall has been more measured than America’s. Despite widespread horror at the result, European leaders have shown less policy opposition to Trump than the famously supine Republican-controlled Congress. There have been plenty of tough words, but Europeans have not appreciably altered their approach towards the US. Most have not even used the tough words.

This paradox, for even casual observers of the transatlantic relationship, is not difficult to explain, even if it is considered rather rude to talk about. The nations of Europe rely on America for its security and America does not rely on Europe. As George Orwell almost said, “Europeans who ‘abjure’ violence can only do so because Americans are committing violence on their behalf.”[5]

So, even as Europeans complain or protest, they cannot call into question their relationship with America. This asymmetric dependence is the fundamental and seemingly permanent feature of the transatlantic relationship, the inconvenient fact at the base of decades of rhetoric about shared values and common history. And it means that European leaders must find a way to live with President Donald Trump regardless of the threat he presents to European values or whom he shoves out of the way.

But, regardless of how used to this situation we all are, it is not clear that it can or should continue. Trump is the first postwar American president to believe that preservation of European unity should not be a strategic objective for the US. But Obama’s policies already pointed in the direction of a progressively reduced American commitment. Even beyond their problems with Trump’s policy, demographic and political trends in both the US and Europe make relying on the US for security an increasingly untenable proposition.

This Power Audit of US-EU relations asks why this asymmetric dependence persists even into the unreliable Trump presidency, what price Europe is paying for it, and what, if anything, can be done about it. It examines the European reactions to the Trump presidency in more detail across the member states of the EU. It seeks to understand those reactions through an examination of the meaning of ‘America’, both the country and the concept in European politics. Beyond the reactions, it asks what Trump’s election means for both sides’ ability and willingness to sustain the existing bargain of transatlantic relations. For all his radicalism, Trump, it turns out, is more a symptom of the rot in the relationship than a cause.

Madman, Messiah, or Antichrist? European responses to Donald Trump

The EU is a diverse place and has displayed a wide variety of reactions to the Trump presidency. To understand this diversity, we approached political elites in both government and opposition across all 28 member states, surveying their reactions to Trump’s election and to the early months of his presidency. A number of common themes emerged, and we have divided the responses into three ‘Trump effects’ on the EU: the Regency Effect, the Messiah Effect, and the Antichrist Effect. We explain each below, and the table shows the rough distributions of the effects across European governments and parties.

The Regency Effect

In the late eighteenth century, the British aristocracy began to suspect that their king, George III, was mad. Exacerbated by his distress at losing the American colonies, the king’s behaviour became increasingly erratic – sometimes he would speak for hours without pause, often foaming at the mouth. Various calumnies spread about his illness, including the story that the “King had walked up to an oak tree in Windsor Great Park, took a branch in his hand, and entered into a conversation in the belief that he was talking to the King of Prussia.”[6]

Even though many of these stories turned out to be ‘fake news’, they reflected a general sense that the affairs of state were not in competent or even sane hands. The British elite responded to the problem of a monarch not in his right mind by turning to the idea of a regency. Parliament empowered the Prince of Wales to act as regent with the full powers of the king, even as George III continued, technically, to reign.

Trump has not spoken to any trees lately. But he does, at times, stare at the sun and his fitness and even mental stability have repeatedly been questioned.[7] Many, in both Europe and America, have hoped and expected that a type of regency concept would assert itself in American governance. As with George III, they hope that, rather than governing, Trump will be governed by his advisers, the Congress, the courts, and American civil society generally. Most European reactions to the Trump administrations are examples of this Regency Effect.

On a certain level they have little choice. Before the election, some European leaders felt able to declare Trump’s candidacy dangerous in the most undiplomatic of terms. The British prime minister, David Cameron, for example, called candidate Trump’s proposal to ban Muslims from the US, “stupid, divisive, and wrong.”[8] Even for those who kept quiet, a large majority viewed a Trump presidency with a combination of incredulity and horror. ECFR research from that period showed that in nine countries, political elites expected that, if Trump won the presidency, the US would become the most destabilising element in the international system.[9]

But almost immediately after the election, these apocalyptic images evaporated, and were replaced by a mildly optimistic wait-and-see approach. The concept of most governments was (and remains) that Trump himself was not the key element for understanding US foreign policy under his administration. What mattered were the people he appointed to key positions and the power balances between them – the politics of regency.

In our travels across Europe after the election, variants of the Regency Effect were so common that we took the opportunity of asking a slightly tipsy Italian official why, after so much ink was spilt over the importance of the US election, everyone so suddenly and fervently believed that Trump did not matter. His response was telling: “We have to believe it. We don’t know what to do if it is not true.”[10] Another European official took a more sanguine view: “We made the decision that until we felt more comfortable with Putin than with Trump we would have to stick with the Americans. This admittedly was a low bar.”[11]

Accordingly, European governments scrambled to establish contacts with the personnel of a new administration with which they had had very little prior contact or understanding.[12] The most dangerous place on earth quickly became standing between a European embassy and the presidential transition team.

The first several months of the Trump administration have subjected this view to a rollercoaster ride. On the one hand, Trump appointed strongly nationalist officials such as Steve Bannon, Sebastian Gorka, and Peter Navarro to key White House positions. But at the same time he picked members of the Republican establishment as well as sober-sounding generals for many key positions, including General James Mattis as defence secretary and ExxonMobil chief executive Rex Tillerson as secretary of state.

Despite these appointments, Trump withdrew from the Paris climate change agreement and threatens the Iran nuclear deal, both of which many Europeans hold dear. He has intermittently continued to trash Europe and especially Germany, while maintaining a studious silence on all manner of Russian sins, including Russia’s interference in the US election.

But many of his advisers have more consistently sought to reassure European allies. Even if Trump has a soft spot for Russia’s president, they whisper to their European counterparts, America will stand up for the interests and values of allies. This effort began one month into the Trump presidency when a trio of high-level US officials – Mattis, Tillerson, and the vice-president, Mike Pence – arrived in Europe for various high-level meetings at NATO, the EU, and the G20. This has continued, with frequent trips to Europe, particularly by Pence and Mattis. Throughout, they have brought a clear ‘regency’ message: pay no attention to the president of the US.

Overall, the president remains unpredictable. His “America First” philosophy and his protectionist impulses make him, at base, antagonistic towards a strong transatlantic relationship. Nearly every week brings new Twitter evidence that Trump remains who he has always been and cannot be contained by his advisers.

European leaders issue principled statements objecting to his outbursts, but they avoid any sort of policy response. So, for example, when Trump controversially contended that there were some “very fine people” among the Charlottesville neo-Nazi protesters in August 2017, British prime minister Theresa May retorted, “I see no equivalence between those who propound fascist views and those who oppose them. I think it is important for all those in positions of responsibility to condemn far-right views wherever we hear them.”[13] But rhetoric was the extent of the response.

European officials also privately note that Trump’s rants have had very little impact on US policy. Thus far, policy on Russia has perhaps been the starkest example of the disjuncture between presidential rhetoric and policy reality. Trump has maintained an unusual consistency in his unwillingness to criticise Russia or Putin. But on the ground, the US has continued, and even increased, its support to the European Reassurance Initiative (ERI), which was Barack Obama’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Trump’s 2018 budget request included a 41 percent increase in the funds for the ERI and an increased US troop presence in eastern Europe.[14] The US has not only maintained Obama-era sanctions on Russia, but, against the objections of Trump, the US Congress overwhelmingly passed new sanctions on Russia for interfering in the US election. It also limited the president’s ability to waive them. The political scandal over the Trump campaign’s alleged collusion with Russia during the election has particularly reduced the president’s manoeuvring room on this issue. He appears isolated on Russia even within his own administration.

Similarly, on Afghanistan, Trump spent years railing against the “enormous waste of blood and treasure in Afghanistan” and advocating a policy of withdrawal.[15] In July 2017, he continued to assert that the US was losing the war in Afghanistan and that he was considering firing the general in charge of the war. Yet the following month, in a speech read between gritted teeth from a teleprompter, he announced he would continue the current strategy and send additional US troops to Afghanistan.[16]

For many in both Europe and America, this lack of implementation as well as other developments in Trump’s first months – the replacement of the ideologue Michael Flynn with the more pragmatic HR McMaster as national security adviser, the ousting of Steve Bannon, and the appointment of General James Kelly as chief of staff – demonstrate that the regency is slowly consolidating itself. To reinforce this view, many European leaders make sure to differentiate between the longstanding relationship between their country and the US, and the temporary relationship with its current president.[17]

The image emerges of a mad king who likes to get attention, while behind the throne his sober regents are dealing with their counterparts in Europe. His tantrums are mostly ignored while he wins praise for his occasional willingness to mouth the words of speeches written by his regents.

The Messiah Effect

In 132CE, Rabbi Akiba, the greatest of the Talmudic sages, declared a rebel Jewish leader named Simon bar Kokhba to be the Messiah – the anointed one who would herald a new age. Bar Kokhba had achieved some stunning early victories against the occupying Romans and Akiba hoped to profit from his revolt to score some advantage over competing religious authorities within Judea. In the end, bar Kokhba proved to be a false messiah, the revolt failed, and, far from a new age, the Jews were nearly wiped out and their descendants exiled from Jerusalem for nearly 2,000 years.[18] But, despite such pitfalls, the idea of a messiah persists, specifically because the idea of a ‘new age’ is often helpful in internal struggles.

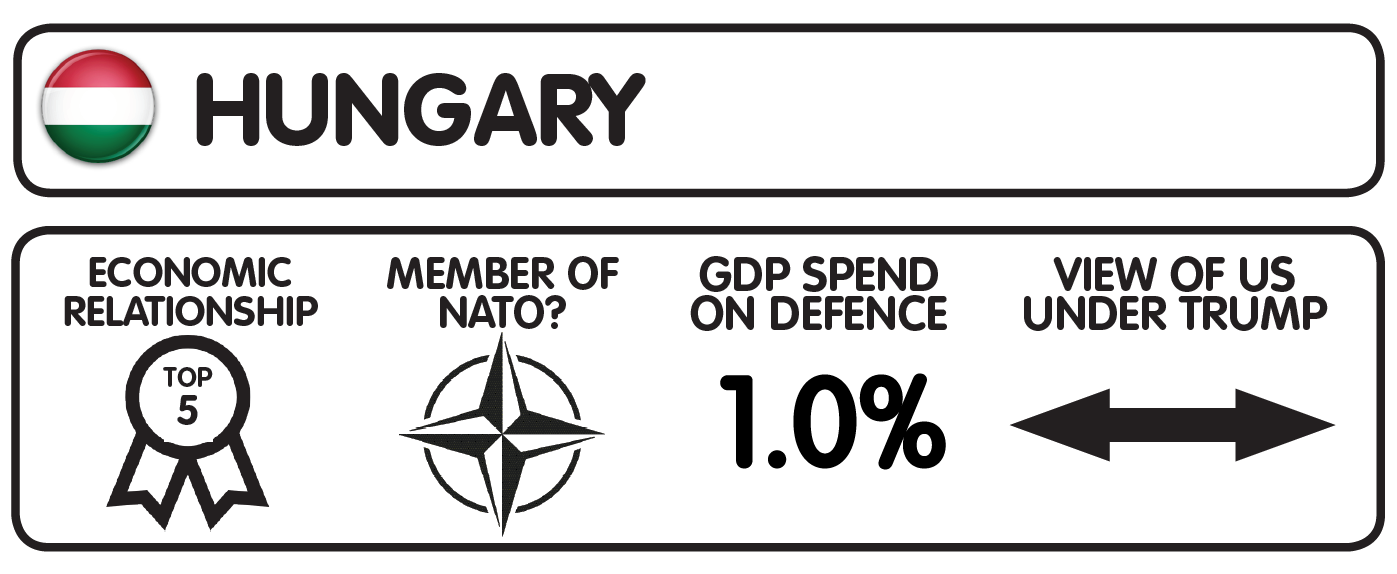

Trump is probably not the messiah. But in his elevation to the most powerful position in the world some in Europe do see a new age that some Europeans welcome. Viktor Orbán, the prime minister of Hungary, put it in vaguely religious terms soon after Trump’s election: “We have received permission from the highest worldly place that we can put ourselves in the first place, too.”[19] Orbán’s relationship with the previous administration had been fraught, especially after criticism by the Obama administration of the state of the rule of law and corruption in Hungary. Now, with the sanction of the American president, he seems to believe that the old age of political correctness is over and that he can openly say what he thinks about the failures of immigration, liberalism, and democracy promotion.

And he is not alone. All over Europe, nationalist, anti-immigrant, and anti-mainstream movements have felt emboldened. Lega Nord in Italy portrays itself as the only Italian party in accord with Trump’s sovereign, nationalistic, and anti-immigration political programme. Leaders of far-right parties in Belgium and the Netherlands have spoken about a new patriotic movement that would spread around Europe because of Trump’s election.[20] The far-right German party Alternative für Deutschland sent Trump a congratulatory message outlining the overlap between their policies, ending with a distinctly un-German “God bless you and your family, God bless America and Germany.”[21] Formerly marginal extreme-right groups, such as Volya in Bulgaria and Imperium Europa in Malta, are more vocal about their views and have seen a small boost in the polls.[22]

Some of these parties have also had an easier time in their diplomatic relations with the Trump government. In contrast to the mad scramble of many governments, the Hungarian ambassador to the US, Réka Szemerkényi, had met Trump three times by March, and had also spoken with Mike Pence and several cabinet members. Fellow Trump enthusiast Miloš Zeman, the Czech president, was invited to the White House; his predecessor Václav Klaus did not have this pleasure in his ten years in office.

For Hungary and others, Trump is at least a slightly problematic messiah. He has thus far not really supported Orbán in his struggles with the EU or over his attempts to close the Central European University in Budapest. But they retain hope that over time Trump will gain enough control over his own government to support an agenda they believe he supports at heart.

Similarly, in Poland, the governing Law and Justice Party believes that Trump represents true Americans who rebelled in the name of the Christian and conservative West against the dictatorship of political correctness, gay rights, and liberal immigration. Trump’s affinity with Russia and Putin tempered the Polish government’s enthusiasm for him during the campaign and during the early months of his presidency. But the lack of change in America’s Russia policy, and particularly Trump’s visit to Poland in July, have reinforced the notion that Trump is an ally in the struggle against liberalism in Europe. The Polish government seems to have decided that even a partial ally in the White House represents a new and valuable asset in its domestic struggles.

Even in the UK government, which overall has taken a regency approach to Trump, one sees elements of the Messiah Effect. Trump and his “America First” philosophy, and its echoes of “taking back control”, came at a good time for British prime minister Theresa May in the Brexit negotiations. She rushed over to Washington immediately after his election, revelled in his promises of a post-Brexit UK-US trade deal, and invited him on a state visit to London. At least temporarily, her government gained more confidence in its strategy of hard Brexit or bust.

The Regency Effect implies that mainstream politicians will tolerate a lot of rhetoric from Trump, hoping to keep their bilateral relations alive and doing business with Trump’s minders until the storm passes. But in the meantime, the Messiah effect may have an impact in their backyard. Trump’s immigration policies, for example, even if they have been limited by the courts and the Congress, provide a precedent for debates on refugees and Muslim integration in Europe. Perhaps worse, Trump is providing cover for a host of outrageous ideas that were once anathema but which have acquired legitimacy through their expression in the White House. These include a ‘Muslim ban’, as promoted by several extreme right parties, or a reluctance to work on climate change, as supported by the Poland’s ruling Law and Justice party. In this sense, Trump’s very existence is helping to move once radical parties into the European mainstream.

But, of course, there is a risk for the anti-establishment parties too. Bar Kokhba, after all, led his followers into ruin. As Maimonides noted a thousand years later, “Rabbi Akiva was a great sage, one of the authors of the Mishnah, yet he was the right-hand man of Bar Kokhba, the ruler, whom he thought to be King Messiah. He and all the sages of his generation imagined Bar Kokhba to be King Messiah until he was slain unfortunately. Once he was slain, it dawned on them that he was not the Messiah.”[23] Some of Trump’s apostles have already started to abandon him, mostly because of the change he did not bring to the Washington ‘swamp’.

The Antichrist Effect

One man’s messiah is always another’s Antichrist. Both are inspiring in their own ways: the idea of a messiah gives an example to exalt and emulate; the Antichrist establishes a clear challenge and gives opponents political space to adopt new, radical solutions. As Martin Luther put it, “I feel much freer now that I am certain that the Pope is the Antichrist.”[24]

For a minority of European politicians, the election of Trump points towards a new European reformation. Trump’s election is, in this view, only the latest in a series of moral and strategic failings by the US – the responses to ECFR’s survey cited the invasion of Iraq, the torture and rendition programmes of the ‘war on terror’, the NSA wiretapping scandal, and the lack of leadership on climate change. The sense of moral example from the US, especially strong in some of the former eastern bloc countries, is diminishing. All this predates Trump, but he has certainly not reversed the trend as Obama did early in his presidency. The survey demonstrated that, in most countries, elites expect the image of the US in Europe to worsen dramatically under Trump. So far, polls bear that out.[25]

The first to capitalise on this effect politically was Emmanuel Macron in his successful campaign for the French presidency in May 2017. His opponent was Marine Le Pen, a Trump ‘apostle’, who declared on the day of Trump’s inauguration that “the EU is dead, but does not know it yet.”[26]

By contrast, Macron ran on the idea that, far from a constraint on French independence, France’s membership of the EU was the key to maintaining French sovereignty and retaining influence in global affairs. While Macron did not reject cooperation with Trump’s America, he outlined a vision in which France and Europe do not rely on the US or NATO as the main determinant of their status on the global stage. His vision rests more on further integration in European defence, which he sees as key for Europe to “hold its destiny in its own hands.”[27] His victory has emboldened others in Europe to think that opposition to Trumpian policies of disintegration and isolation might be a winning formula. Macron’s policy of standing up to Trump carried over into his first meeting with him as president. It ultimately gave him the credibility to invite Trump to France in July 2017 while avoiding the label of apostle.

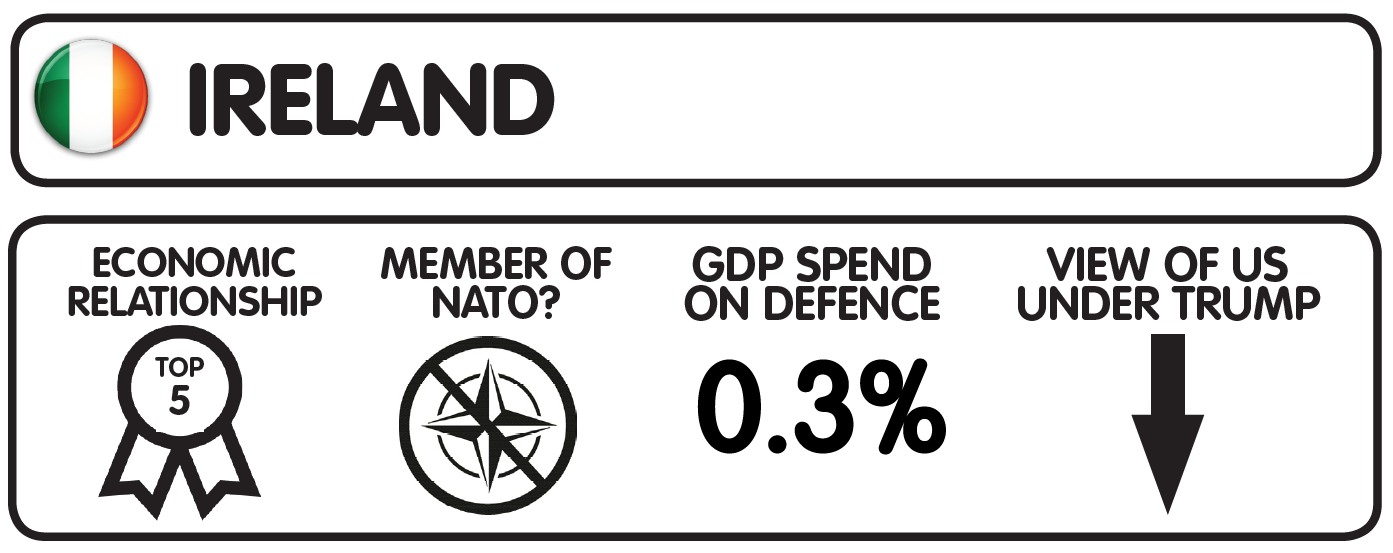

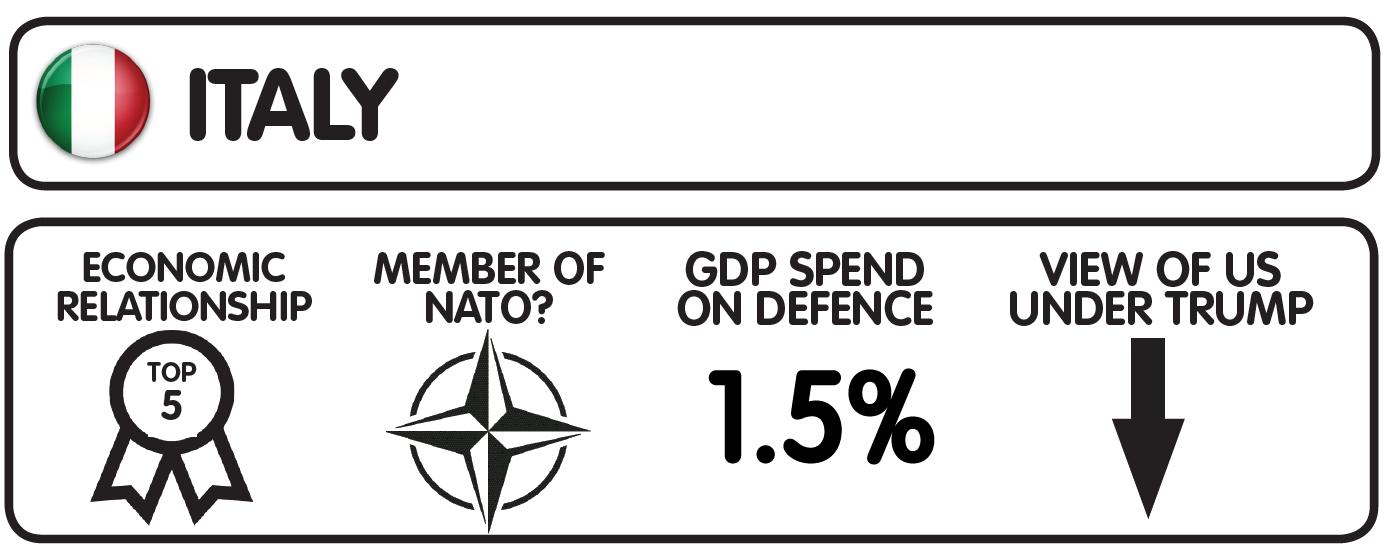

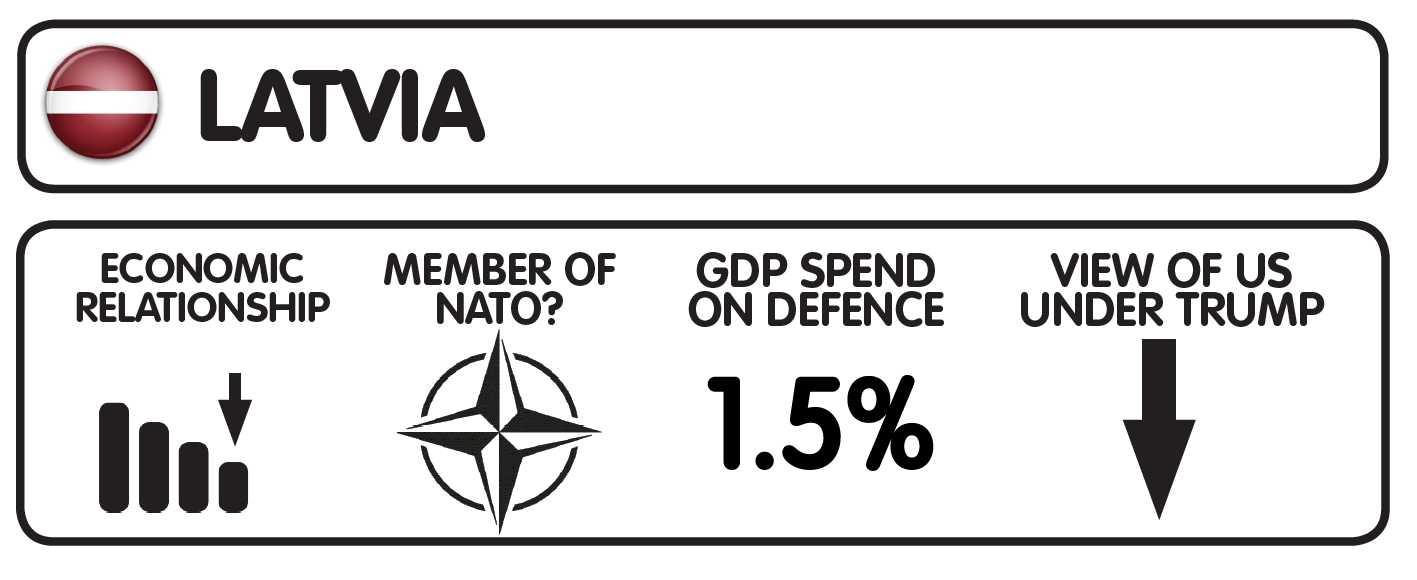

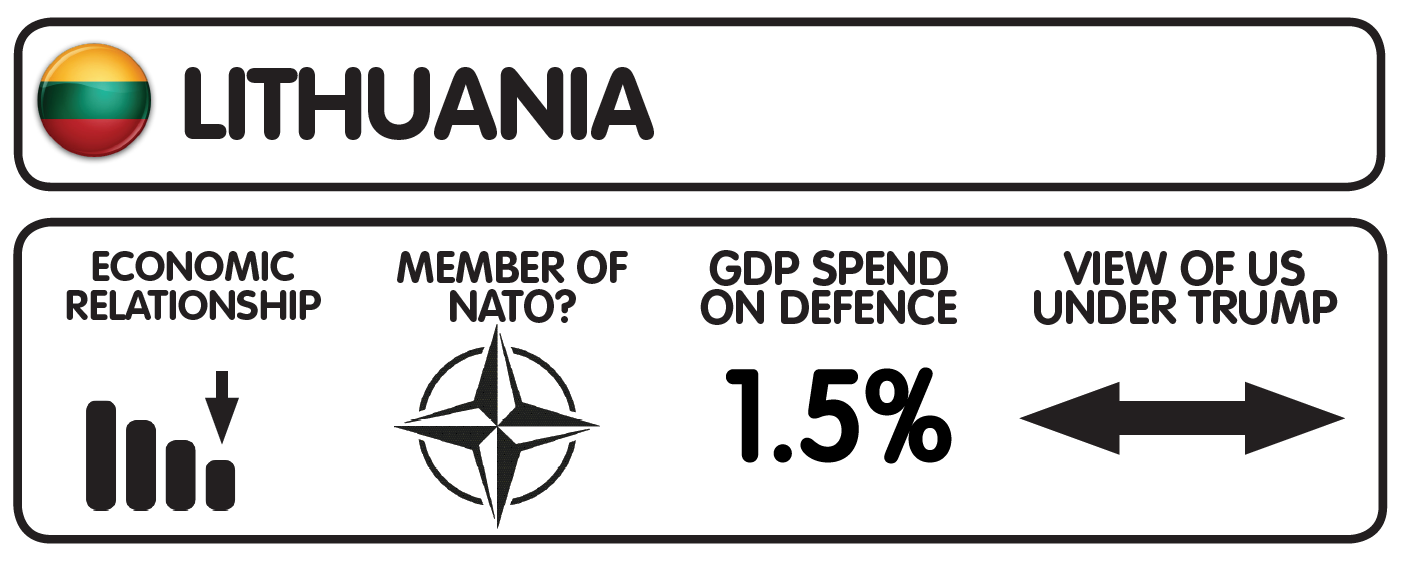

France has long stood out in its willingness to act independently of the US; most others have generally felt more dependent. But in some other countries, such as Italy, Latvia, and Sweden the EU has begun to take over the role of the moral example to follow, or is seen to be making a last stand in a formerly joint project of spreading liberal values. The Trump shock has also led to movement in a longstanding issue in EU cooperation: defence. In 85 percent of countries, respondents thought their country should spend more on defence, either to become independent from NATO or to invest in EU defence.

The remaining countries are already spending enough, or are on a path of expansion to spend enough next year. This indicates that security is a new focus area for the remaining 27 EU member states; one that they could work on together more effectively in the future, even under the idea of flexible cooperation. An increase in spending has been on the agenda for a long time. But the discomfort that comes with a more uncertain transatlantic relationship has proven an important stick with which to cajole countries into action.

Unfortunately, reformations are never easy. In the EU’s case, it is not clear that the new impetus for reform coming from Trump’s election (and from Brexit) is strong enough to overcome the traditional resistance to increasing European defence cooperation. The newer centrifugal forces come from the dual refugee and euro crises that have split Europe along north-south and east-west lines and made European cohesion yet more difficult to achieve.

ECFR’s survey revealed that opinions between countries were perfectly split on whether Trump would have a positive or negative effect. The positive expected outcomes centred on necessity: namely, that the possible loss of the American umbrella will make Europeans work together better. On the other hand, internal splits were the main negative outcome likely to emerge from Trump’s election. This could emerge as populist parties grow in confidence, but also because many political elites hold firm to the belief that if the American president stops supporting European integration, Europe will not move forward.

The remaining question is: why do Europeans believe in such a central role for America in European security?

The power of disinterest

All three effects – Regency, Messiah, and Antichrist – are in operation in Europe and have had important political consequences. But our survey shows that the main one has been the Regency Effect and the semi-conscious decision to assume that Donald Trump’s presidency will not fundamentally change America or the international system.

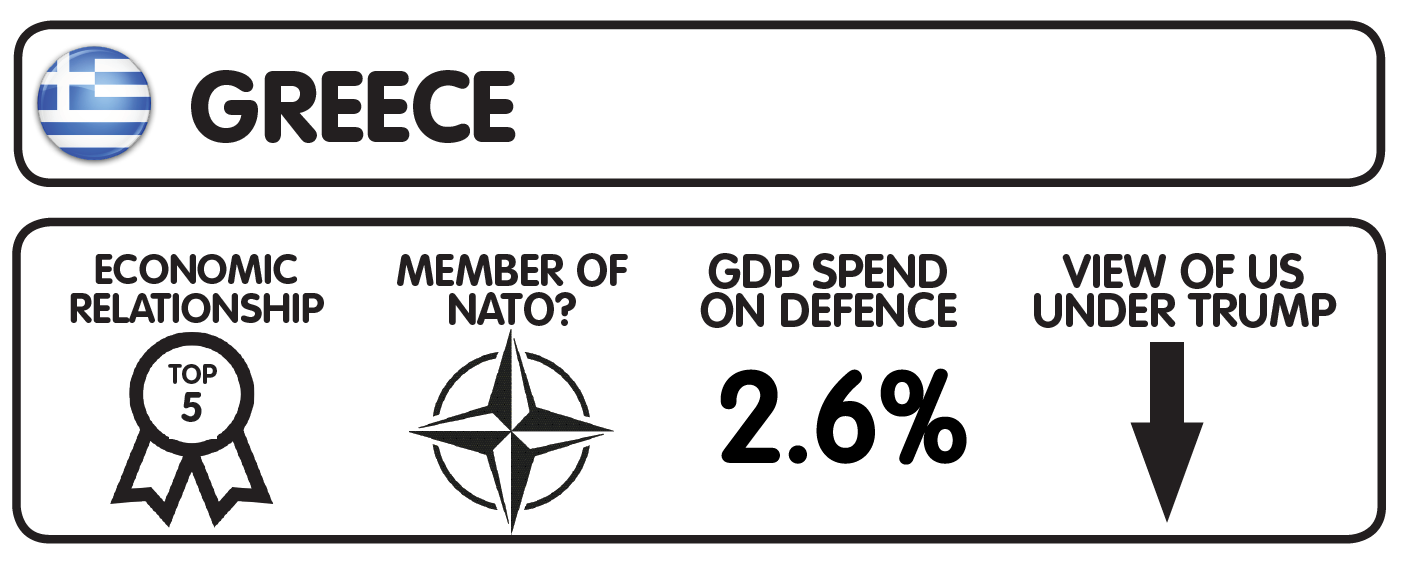

For many, this result presents no puzzle at all. Even tipsy Italians, like the official we met earlier, understand deep in their marrow that the nations of Europe depend on the US for their security. They need to maintain an effective relationship with America and whomever the American voters, in their infinite wisdom, see fit to put in the White House. Our survey shows that that this effect remains as strong as ever. The member states in the east look to America for security against Russia; the member states in the west look to America for security against Islamist terrorism. And, in a new twist, Greece – traditionally the country in the EU with the most anti-American attitudes – now looks to America for protection against Germany.[28]

The dominance of the Regency Effect is not surprising, but it begs the question of why this is the main reaction. Over recent decades we have become so used to the nature of the transatlantic bargain that we have forgotten how historically and geopolitically anomalous it is. Why does a rich continent of 500 million people depend on a distant nation of 300 million to defend it against much poorer and weaker threats on its borders? Why do the nations of Europe outsource this most sacred of national responsibilities?

To grasp why, one needs to understand the meaning of America and the American president in Europe. As in any longstanding relationship, the European idea of America is complex. Europeans alternately and variously love America, hate America, envy America, and look down on it. The constant in all these emotions is that America is important to Europe, a part of domestic politics on which everyone has an opinion.

The cultural impact of technology has made America even more present in Europe. First television made Europeans aware not only of who the American president was, but also what it was like to be a single person trying to date in New York. More recently, a recurrent theme in our survey was the impact of companies such as Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Netflix. Europeans can now follow the life of the Manhattan single twenty-something minute by minute, and order their clothes with next-day delivery.

This now also extends to former communist countries which were excluded from the postwar US influence. Our surveys reveal that, in Hungary, a growing start-up culture references the US, and new companies there set the US as their ultimate destination. Over the past ten years in Lithuania, English has overtaken Russian as the most important second language. In Slovakia, American-style restaurants are now prestigious places to eat for the younger generations, and English expressions have started to enter the language.

In part for these reasons, the US president attracts a lot of attention in Europe. Indeed, the European obsession with the American presidency has become so routine that it is basically just accepted as part of the furniture. But it is extraordinary – even by January 2016 one survey showed that between 85-90 percent of Europeans could identify the two leading US presidential candidates.[29] But after similar elections in France and Germany, only 38 percent of Americans were able to identify the winner of the

French presidency and only 4 percent could identify the German chancellor.[30] One presidential candidate, Gary Johnson, could not identify even a single foreign leader.[31] As if seeking approval from an aloof father whom they both deplore and rely on, Europeans have for decades obsessed over his every action. They seek his support in disputes with their siblings, crave his occasional visits, and rejoice in a casual mention of their role.

My (Shapiro’s) understanding of the role of the US president for Europeans began in a fish restaurant. In fact, it was my favourite fish restaurant in Washington, which was why I accepted the lunch invitation from the Spanish embassy. But I knew the price in advance. It was 2010 and Spain held the rotating presidency of the EU. They desperately wanted Obama to attend the US-EU summit in Spain and they were pulling out all the stops. If they were willing to cough up for the seared tuna to talk to a low-level official like me, they had clearly reached a desperate state in that effort. Between bites, I explained again what they had already intuited: Obama would likely not go. As I ordered dessert, the Spanish officials did not bother to hide their deep disappointment. The US government offered a substitute. But without the American president the summit had no meaning at all. Despite the important outstanding issues in US-EU relations, the Spanish soon cancelled the summit altogether.

As commentators often note, Americans do not reciprocate this obsessive attention. No European official has ever eaten a fancy lunch on the slim hope that European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker will visit Washington. The US foreign policy community recognises the importance of Europe but this falls well short of the obsessive attention paid by Europe to America. An August 2017 research trip to Washington showed that national security leaders, both inside and outside the government, are preoccupied with Trump’s latest antics and are focused on the domestic impact of US policy toward Russia and the Middle East.[32] They could not even sustain a conversation on the future of the EU. For them, Europe is mostly a nice place to visit and to hold conferences on Middle East peace.

But Americans’ lack of interest in Europe is not a bug – it is an important feature of the transatlantic relationship. Europeans want a protector whose own interests are remote from the internal struggles of Europe. They want a partner who will provide stability and security without posing a threat or taking a stand on the issues that divide Europe, such as immigration or fiscal policy. The Greek attitude towards Germany demonstrates the problem. Greece needs help. But because of the EU, and especially the euro, Germany is too involved in Greek domestic politics to trust as a security provider.

Even on foreign policy issues, as political scientist Ivan Krastev notes, “the external threats that the EU faces divide rather than unify the continent.”[33] Of course, many European states have differences with the US on a variety of foreign policy issues, particularly in the Middle East. But because America’s main foreign policy interests are in other theatres, they either matter little to European domestic politics or European leaders can hope that they will change.

On the foreign policy issues that really matter to European security, principally Russia, terrorism, and stability in the southern and eastern European neighbourhoods, the US as a distant power has less fixed positions than the powerful European states do. On Russia, for example, US policy has fluctuated dramatically in the last three decades, from hostility to reset and back again. Trump’s view offers the chance for another reset, but the opposition to it in Congress implies that deepening hostility is just as likely. European national positions on Russia, though they vary greatly across the continent, have stayed much more constant. They are largely fixed by geography and history.

America’s disinterest and consequent flexibility mean that America is the wild card in European foreign policy debates. European leaders hope not so much for a neutral arbiter as for an ally in their internal struggles with other European states. For this reason, individual European member states have always been keen to maintain their individual bilateral relations with the US, even as they took measures to create a supposedly unified European foreign policy apparatus.

In the period after the creation of the office of EU high representative for foreign affairs in 2009, meetings with national European officials in the US State Department would typically begin with a plea for the US to accept that the EU was a unified actor.[34] But they would generally end with a plea for US support in some internal European struggle, such as keeping Germany off the UN Security Council. The message was clear: respect our unity except when our country needs your support.

Our survey revealed that 11 EU member states believe that they have a special relationship with the US. A direct relationship with the American president is extremely valuable in asserting this special relationship, which is why it meant everything to the Spanish to try to bring Obama to their summit.

For Europeans, America means security and stability. But, more than that, it means disinterested security. Europeans certainly want protection from Russia and terrorism, but, working together, they could provide that themselves. The problem is that they also want political protection from each other. And only America can provide that.

Trump and Obama: What’s the difference?

Such is the transatlantic bargain that the madness of President Trump threatens to disrupt. For all its weirdness, that bargain has served both sides of the Atlantic well over the years. As the dominance of the Regency Effect implies, foreign policy leaders on both sides of the Atlantic are keen to protect it. But regency will only succeed if Trump is really the problem. And, even though Trump’s ideology does represent a new threat to the alliance, there is ample reason to suppose the problems run deeper than one mercurial president.

Trump has been clear that he views the transatlantic relationship in instrumentalist terms. Unless it is radically reshaped, Trump claimed during the campaign, America will simply walk away from Europe, leaving it to deal with its problems on its own.

American foreign policy has long included a desire for more equitable burden-sharing.[35] But previous US efforts to bring this about accepted that America’s best partners are democracies, that America’s own prosperity rests on a broad global system of trade and investment that Europeans contribute to, and that Europe’s security must be protected – by Europe if possible, and by the US if necessary.

Previous postwar American presidents have explicitly looked for a more equitable partnership with Europe, but they believed that Europe’s security and prosperity were a core interest of the US. They have therefore been wary of abandoning Europe and leaving it to its own devices.

Trump, in contrast, believes in walls and in oceans. In this view, America can and should stand aside from problems in other regions. Trump’s new approach has increased American bargaining power, but at the cost of putting at risk the entire alliance. A striking result from our survey is that few in the EU, even those motivated by the Antichrist Effect, want to see the end of this basic bargain.[36] Most hope that the regency will help them preserve it.

The problem for the regency is that Trump’s radicalism, his profound ignorance of policy, and his bizarre antics obscure what has become a clear if a much more slow-paced trajectory in American policy. In fact, the US has been scaling down its global commitments, and particularly those in Europe, for several years. As of today, it has fewer troops stationed abroad than at any time since it started tracking such data in 1957.[37]

Among its other lessons, the 2016 presidential election starkly revealed that a deep gulf had opened up between the American electorate and its foreign policy establishment. The establishment in both parties has long made the case that American global ‘leadership’ and American efforts in distant regions are necessary to sustain global stability. They thus ultimately serve American interests.[38] In a world of new and rising powers, they seek to ‘adapt American leadership’ to the new context rather than find a new role for the US.

The American public has always been a somewhat disgruntled supporter of this leadership approach. Mostly they were too busy with other issues and too secure to really care. But as homeland security has become more of a concern and the costs of inconclusive foreign wars have increased in recent years, they have become less tolerant of America’s traditional leadership role in Europe and the world. Fifty-seven percent of the American public now say that they want to reduce American commitments abroad and to focus on more strictly American needs.[39] They do not accept that the abstract foreign policy concepts of ‘leadership’ and ‘regional stability’ have direct payoffs for America.

Obama’s foreign policy tried to compromise between the establishment and the public view. He understood and broadly accepted the need for American leadership, but insisted on reducing America’s costs and commitments if he was to be able to sell an ever more expensive leadership to an increasingly self-interested public. This approach underpinned his efforts to reduce American commitments in Iraq and Afghanistan, to avoid US intervention in Syria, and to scale back the American presence in Europe.

Unfortunately, Obama’s efforts at compromise meant that his own foreign policy apparatus largely did not understand or accept the political constraints that he felt so keenly on the campaign trail. The foreign policy establishment excoriated him for a lack of strength and leadership. His own national security officials, largely drawn from that establishment, constantly pushed for more US involvement abroad in, for example, Syria, Ukraine, and Afghanistan. At times, his efforts to partially accommodate what one of his closest aides call the “blob” resulted in policy, as in Syria, for example, that dissatisfied all sides.[40]

Clinton tried to represent this establishment foreign policy view on the campaign trail but found little success with it. She soon de-emphasised that message in favour of domestic themes. By contrast, Clinton’s primary opponent, Bernie Sanders, and Trump both generated enthusiasm through their rejection of the establishment and, in part, its traditional foreign policy.

Given Sanders’s surprising strength in the Democratic primaries and Trump’s even more surprising victory, at least one political lesson is very clear from 2016. The foreign policy establishment lost. It was nearly completely unified in its opposition to Trump and yet it made no difference at all. Trump demonstrated that a president can be elected without paying any heed whatsoever to the “blob”. Future presidential candidates will take note. Even if they are more sober and globalist than Trump, no one will put the case for continued American global leadership to the American public.

The “blob” has not surrendered. The Republican foreign policy establishment has provided Trump’s regents. In the corridors of power in Washington, they advocate, often effectively, for continued and even increased commitment to the conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan, as well as for continued adherence to the Atlantic alliance. Trump’s lack of attention to detail, and the lack of personnel in the foreign policy apparatus willing to implement his agenda, mean that his actions tend to create confusion rather than radical reform.

Unfortunately, presidential incompetence and the public’s lack of interest is a weak foundation on which to build a durable foreign policy. The disinterested nature of America’s security relationship with Europe means that its commitment to the continent is usually first in line for the foreign policy chopping block. For a public that wants to put America first, it is particularly hard to explain why America should protect a relatively stable continent of rich democracies. Trump has made a lot of rhetorical hay out of Europe’s freeriding on America. Neither the American foreign policy establishment nor their European allies have found an effective political counter-argument.

All of this creates a deep challenge for Europe. Europe has an intense strategic and psychological dependence on the US, yet Trump’s America, and arguably any future America, is both uninterested in, and unable to fulfil, its traditional role in Europe. The states of Europe should be preparing for that day. But, as the mild reaction to the radical Trump presidency shows, internal divisions mean that by and large they are not.

Towards a post-American politics in Europe

The geopolitical logic behind Europe reducing its dependence on the US is very strong. At the moment that Trump and the American political trends he represents are highlighting American unreliability, the Middle East is becoming ever more unstable, Russia is becoming ever more threatening, and Africa is becoming ever more crowded. Europe’s inability to credibly deal with these issues is a key part of why its people have lost confidence in it. As Krastev reminds us, “the old continent has both lost its centrality in global politics and the confidence of Europeans themselves – the confidence that its political choices can shape the future of the world.”[41]

The problem is not the logic. It is that, when it comes to transatlantic relations, ‘Europe’ does not exist. The EU is not capable of agreeing on collective goals and strategies when it comes to the US. The member states own the security relationship with America and, as our survey implies, for most of them it does not ‘hurt’ to depend on the US for security. Or at least it hurts less than the alternative of depending on other Europeans.

Any strategy for overcoming this collective action problem must start with the member states, not with a Europe that does not exist. And it must address the security needs and political fears of the individual member states, not simply imply that European dependence is a result of lack of effort. It must chart a path that describes why enough member states would choose to reduce their dependence on America for security (and why the rest would feel forced to do so).

This means, for example, that independence is not simply a question of increasing defence spending. Collectively, European members of NATO already spend $265 billion on their armed forces, nearly four times what Russia spends.[42] Even massive increases in spending would make little difference without a political commitment to achieve such independence.

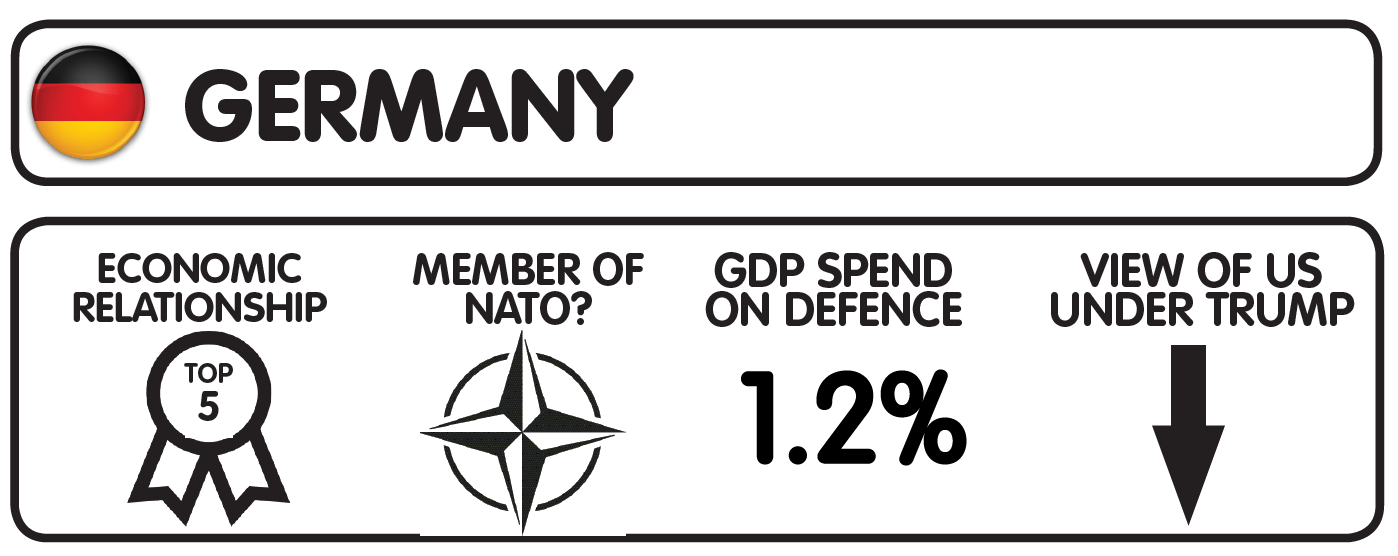

As with much else in Europe these days, the answer must begin with Germany. In the Trump era, Germany has become the key swing state on transatlantic relations. For the most part, it has fallen under the sway of the Regency Effect, as its history would predict. But one also detects important elements of the Antichrist Effect. More than most European leaders, the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, has since the start of Trump’s administration been willing to criticise his policies on, for example, immigration, trade, and NATO, and has suggested that Germany can no longer rely on the US.[43] Meanwhile, Martin Schulz, her main opponent in the German election, goes even further. He has called Trump “dangerous to democracy”, accused him of “playing with the security of the Western world”, and vowed to remove US nuclear weapons from Germany.[44]

As the strongest power in Europe, Germany is naturally the European state most receptive to the idea that America’s role is replaceable. But German officials are aware that America’s position in Europe has always depended not just on power, but also on consensus. As the historian Geir Lundestad reminds us, “one reason America could achieve as much as it did [in postwar Europe] is that America’s desires frequently coincided with those of Western Europe.”[45]

Germany’s current problem is not that it lacks the power to replace America; it is that it lacks the consent. For reasons of history and national psychology, it cannot assume a more prominent leadership without partners. Greece’s explicit call for protection from Germany is just the clearest example of widespread European discomfort with German power. And for all the second world war rhetoric that often accompanies complaints about Germany, this is not just about history. Many countries view Germany’s effort to lead Europe during the financial and immigration crises as harbingers of a self-interested approach to European problems. America, for all its self-absorption, is a lot farther away than Germany and its similar tendency to put its interests first creates fewer clashes with its European partners.

All of this means that Germany cannot just depend on Putin’s aggressiveness and Trump’s unreliability to make the case for a post-American security policy in Europe. It must forge a coalition of member states that see its leadership as benefiting them directly. It must also find a mechanism for exercising that leadership that will bind Germany and convince its European partners that it will not abuse its position.

This effort begins with Emmanuel Macron’s France. Recognising this leverage, Macron is explicitly trying to revive the old Franco-German bargain. In exchange for German indulgence on economic issues, Macron offers a close partnership with France that will help legitimate German power to the rest of Europe. The Macron-Merkel partnership has the potential to serve as a moral centre around which, in a time of geopolitical uncertainty, much of the rest of Europe can rally. The recent Franco-German effort at increasing post-Brexit EU defence cooperation is part of this. It is a mechanism to make Europeans comfortable with greater geopolitical reliance on Germany.

Translating all of this into confidence from Europe’s smaller member states, especially those in the east, is a major challenge. The prior question, however, remains whether Germany has really decided to pursue the path of enlightened leadership in Europe. Its regency instincts run deep. French officials report that the Germans seem more interested in using the effort to improve EU defence cooperation to spur further European integration rather than to create more capability for Europe to defend itself. Many apparently still believe in America – even one ruled by an aspiring Antichrist.

A post-American Europe along these lines is difficult, but possible. It is even a path that many in France, Germany, and elsewhere are advocating. But, of course, it will probably not happen. For all the upsetting changes in America and Russia; for all the crises that have rocked the EU in the last several years; and for all the destabilising developments in Europe’s neighbourhood, the member states clearly prefer the old bargain that has served them so well. For the most part, they will cling to it until its demise becomes clearer than truth. During the presidential campaign, Trump boasted that “I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters.”[46] He might some day say the same thing about the transatlantic allies. In any case, no one will block his photo opportunity at the next NATO summit.

Country by country

Economic power

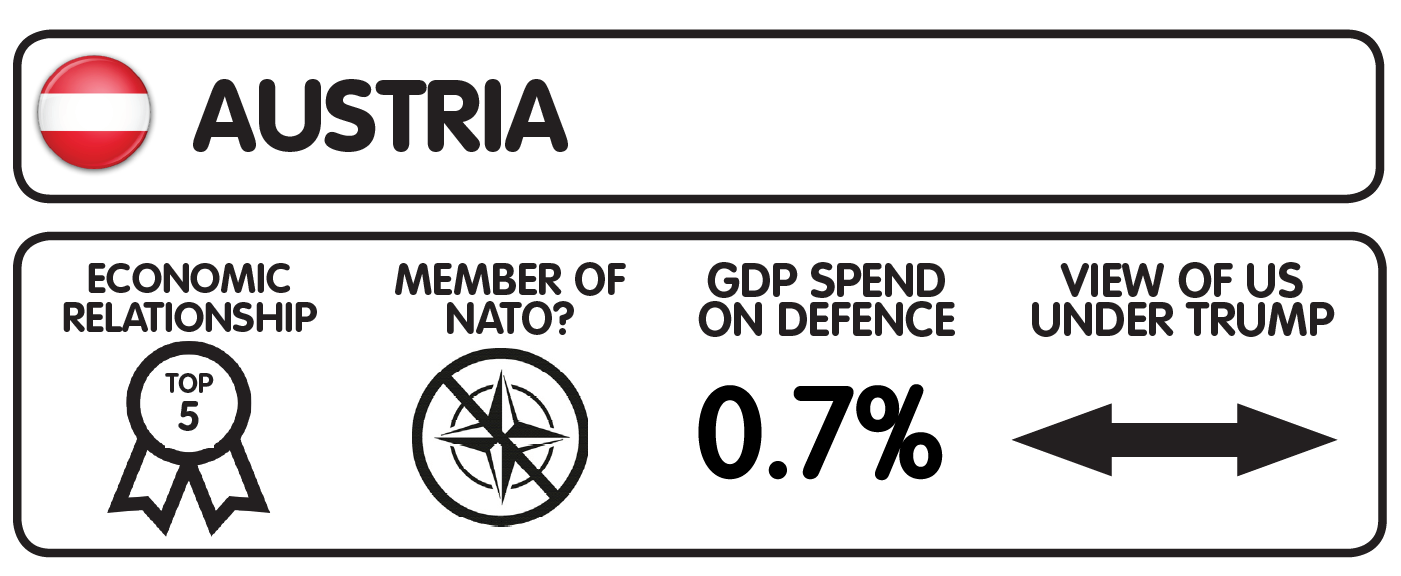

The most important trade partners for Austria are Germany, the United States, Italy, Switzerland, and France. For many US companies, Austria serves as a gateway to central and south-eastern Europe, and is perceived as a good export market for US technology and services. Altogether, some 340 US companies have established subsidiaries around Vienna, contributing to a strong economic network between the two countries. The economic relationship is very important as the US is Austria’s second most important trade partner. Austrian exports to the US represented over $10 billion in 2016, and they include specialised industrial machinery, pharmaceuticals, glassware, electric power machinery, and food products.

Security power

As Austria is not a NATO country, relations with any US government and administration are primarily focused on trade and investment and less on security and sovereignty issues. Whoever is in power, Austria maintains regular contact with the US on developments in the western Balkans, and it participates actively in UN/EU/NATO-led peacekeeping operations in this region. Austria participates in counter-terrorism activities and is in constant dialogue with the US in this field. However, intelligence cooperation is more one-sided: insofar as the US uses Vienna as a hub for its intelligence activities, it is mainly to do with matters pertaining to the UN and other international organisations.

Cultural power

The general public is favourable to the American way of life. But it is not convinced that strong US leadership is good for effectively tackling the challenges that the world, and Europe in particular, face. There is no strong social and cultural impact from the US in Austria and there have been no significant changes in this situation during the last ten years. There is little strong interest in Austria from American political consultants, so their activity in the political domain is also quite limited. There is no strong interest in Austria among American media and technology firms.

Moral power

Austrians are among the Europeans most critical of American leadership. According to one poll, 60 percent view American leadership in the world as negative and only 34 percent as positive. However, the latter has risen 2 percentage points since 2014, and there have been no new polls on this questions since. But the debate in Austria suggests that the image of the US has suffered already due to the presidential campaign but also afterwards.

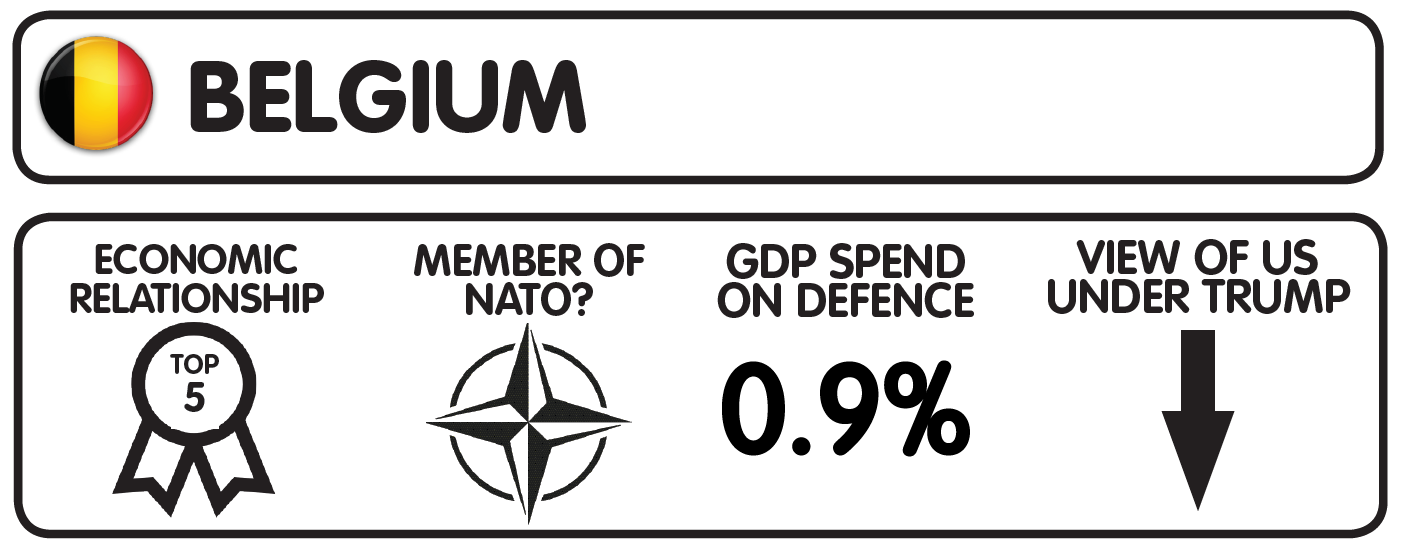

Economic power

Belgium’s relationship with the United States is crucial, as the US is Belgium’s main non-European supplier and its largest non-European customer. In the first nine months of 2016, the US was the country’s fourth largest supplier: it represented 8.4 percent of Belgian imports, around $22 billion. In terms of exports, the US is Belgium’s fifth biggest buyer, accounting for 5.9 percent of Belgian exports, worth $16.7 billion. Key sectors in this relationship are: pharmaceuticals, chemicals, technology, and weaponry. The 900 majority-owned US companies active in Belgium directly employ more than 125,000 people – 4.3 percent of Belgium’s total private sector employment.

Security power

NATO will remain the central pillar of Belgian security, and the election of Donald Trump has not altered this geopolitical fact. The country is aware that the new US administration will insist on a more balanced financial burden-sharing. In this context, political leaders, officials, and diplomats seem to be ready to spend more on defence. Positive statements from diplomats have reassured Belgian politicians and diplomats that NATO will remain at the heart of the Euro-Atlantic defence architecture. The financial burden will nevertheless have to be shared. This rather optimistic evaluation has also been confirmed thanks to several contacts established with other officials from the Trump administration.

Cultural power

The cultural and social impact of the US in Belgium in the last decade can be divided into three phases: the Bush era, the Obama era, and the election of Trump. In the Bush era, Belgian perceptions of the US were rather negative. The invasion of Iraq in 2003 unleashed anti-American discourse. The election of Barack Obama can therefore be seen as a turning point. In Belgium, Obama was seen as much more thoughtful, competent, and peaceful than his Republican predecessor. His presidency initially generated a lot of hope among Belgians. Trump’s election marks a new low point in terms of the image of the US in Belgium. His victory surprised the country and greatly diminished US soft power among Belgians.

Moral power

Belgian officials feel that the US does contribute to the promotion of liberal values on the international stage, but that the role of the European Union is also crucial. Belgium is one of the strongest supporters of both the EU and liberal values, and so it does not intend to rely solely on one country, even though the US is one of its main allies. According to a January 2017 poll, 70 percent of Belgians thought that Trump would not be a good president and only 14 percent of them thought the contrary. Belgian newspapers scrutinise the Trump administration’s every move, and are very critical of him on matters such as the ‘Muslim ban’, and his relationship with Russia.

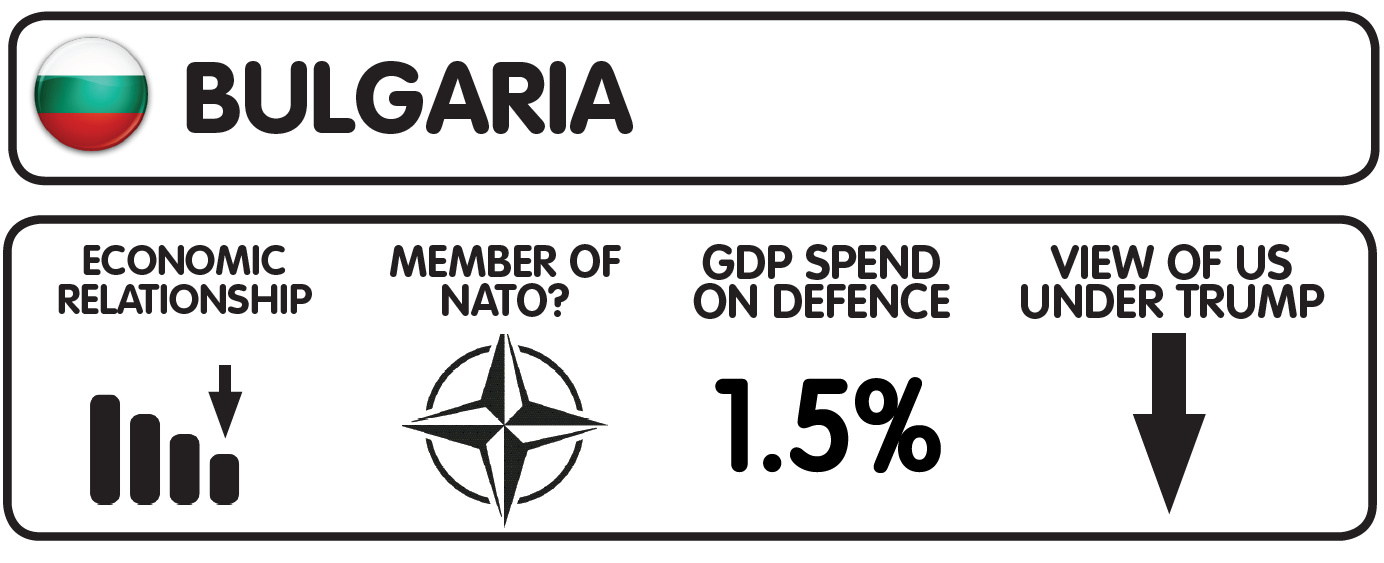

Economic power

The United States was the ninth biggest investor in Bulgaria between 1996 and 2014, mainly in the energy and automotive sectors. Many in Bulgaria consider the US to be a leading economic partner for their country, despite the statistics showing it to be less important than others. European Union countries are Bulgaria’s top trade and investment partners, with over 60 percent of trade and major foreign direct investment flows coming from the EU. Bulgaria does not import oil and gas from the US, but two of its largest coal power stations are owned by US companies – Thermal Power Plant AES Galabovo and ContourGlobal Maritsa

East 3, operating with local coal.

Security power

Bulgaria considers NATO the cornerstone of its security. The effect Donald Trump will have depends mainly on his policy towards the alliance. Even if the US does not disengage from NATO completely, it might not be as active as it has been in the past, and it is clear that Europe should do more for its defence. Experts and politicians agree that Trump’s position means that NATO members are likely to increase their national defence budgets, including Bulgaria. Bulgaria is on track to reach 2 percent in defence spending by 2024. There is a sharp divide of opinion in the country with regard to Russia: while most foreign policy experts and administrators are concerned about a US-Russia accord that leaves Europe out in the cold, there are some who expect and count on this.

Cultural power

In the early 1990s, there was a fascination with the US. It – or rather the image people had of the US – served as one of the templates for the transformation of Bulgarian politics and society. But often this was simply a projection. The late 1990s and early 2000s witnessed the country’s double accession to NATO and the EU with much enthusiasm and high expectations from ‘joining the West’. Fast-forward to the present day and anti-Americanism is commonplace. It is to be found mostly in nationalist, far-left circles, and there appears to be a correlation between pro-Russian and anti-American sentiments; proponents view them as a dichotomy. But there is a twist: since the election of Trump the nationalist far-left has become much friendlier towards the US, and will remain this way as long as relations between Trump and Vladimir Putin remain good.

Moral power

After its own democratisation took place, Bulgaria looked to the US for leadership in promoting liberal values in the Balkans and Black Sea neighbourhood. Currently, the situation is unclear and Bulgaria is not active in democracy promotion. There is a paradoxical situation, whereby mostly liberal pro-Americans have remained pro-American and previous anti-Americans have become pro-American because of their sympathies for the new president. In a way, Trump’s views and supposedly excellent relations with Russia have improved the public image of the US in

anti-American circles, and the US has ‘gained’ new friends. A European Trump Society has even been established. Overall, however, the image of the US in Bulgaria remains largely unchanged.

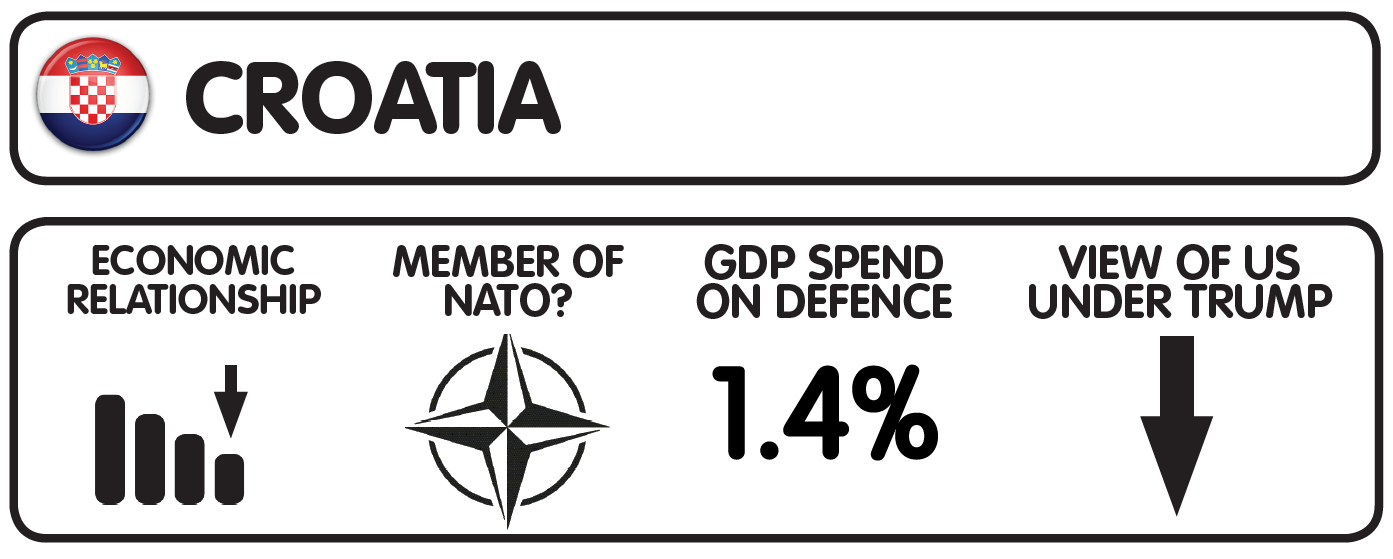

Economic power

The United States is considered to be an important economic and strategic partner in Croatia, but American interests are primarily viewed through the lens of security. Over the last year Croatia’s most important trade partners were European Union member states, which made up 66 percent of goods exports and over 77 percent of imports. The US is not among Croatia’s top five partners economically, although exports have increased significantly. Before the low oil price led to a decrease in US interest, the US invested significant amounts in preparations for tenders for oil research and exploitation of undersea sites in Croatia.

Security power

Croatia primarily looks at the US through the prism of defence and security; NATO is considered to be the main anchor of stability in south-east Europe. As long as Donald Trump’s administration stays committed to the alliance, he will be viewed as materially supporting Croatian national security, sovereignty, and political independence. For Zagreb this is especially important in the context of renewed Croatia-Serbia tensions. Additionally, there is a hope that Trump’s position may actually strengthen NATO – especially when it comes to the 2 percent defence spending requirement. Still, a potential American disengagement from the region is viewed as a scenario which would have disastrous consequences for Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and Montenegro.

Cultural power

Croatia has always expressed its full commitment to programmes supported by the US embassy, which include the organisation of seminars, lectures, summer schools in culture management, professional specialisation, and programmes for young artists. Only one high-profile case of US political consultancy has attracted particular media attention. The opposition Social Democratic Party hired Alex Braun for the 2015 election, causing some lasting reputational damage to the party due to the elevated costs of his PR services. Among numerous examples of cultural cooperation between the US and Croatia, recent examples include a two-year arts management seminar which ended in 2016, organised by the Croatian Ministry of Culture alongside the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and the DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the University of Maryland.

Moral power

Croatia looks to the US for moral leadership, and Croatian politicians rarely fail to mention that the two countries share common Western values. Additionally, the US has provided assistance throughout Croatia’s Euro-Atlantic integration process, promoting lasting political reforms, greater public accountability, democratisation, human rights, and oversight of government operations, as well as a free and independent media. The US is also seen as an active promoter of strengthening the rule of law and equal rights – in Croatia and globally. In general, the public and the NGO sector, as well as the political and diplomatic establishment, continue to frown upon Trump for a number of reasons, most importantly on security.

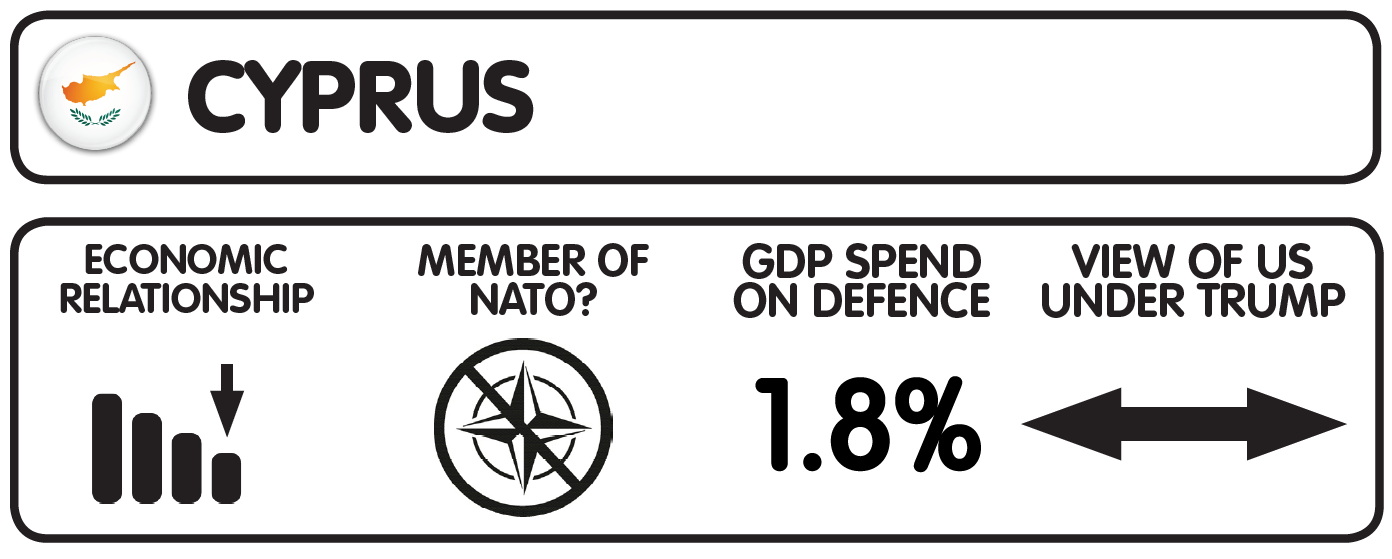

Economic power

It is in the field of politics that the United States is principally a powerful ally and partner for Cyprus, and the economic relationship is less important. The US does constitute an important trading partner, but does not find itself in Cyprus’s top 10: in 2016, the US was the 11th largest trading partner in terms of imports (2.1 percent of total imports), and fourth largest trading partner in terms of exports (2.8 percent of total exports). Exports and projects involving US investment are to be found primarily in energy, financial services, tourism, logistics, and consumer goods. These sectors reflect Cyprus’s main economic activities.

Security power

Security is viewed through the prism of a divided Cyprus. The US, as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council and recognising the Republic of Cyprus as the island’s sole representative, holds vital strategic importance for the country. Although Donald Trump is yet to make a statement on Cyprus (in particular, after the failure of reunification talks in July 2017), US policy is expected to remain unchanged, consisting of a commitment to reaching a comprehensive settlement on the island. Cyprus is not a NATO member state but the current Cypriot government is willing to increase ties with the organisation. However, the Cypriot government believes that Trump will continue to support NATO.

Cultural power

Both sides continue to express enthusiasm over future cultural cooperation. The US has been contributing to cultural life on the island since 1981, first via the Cyprus American Scholarship Programme through which thousands of Cypriot students have been able to study in the US. Since 1997 in particular, this assistance has shifted to promoting bicommunal rapprochement between Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots. A variety of civil society organisations have received grants to increase their fields of work particularly in biodiversity, consumers’ and patients’ rights, and children’s issues. Since 2005, the United Nations Development Programme’s Action for Cooperation and Trust programme has worked with Cypriot organisations to design and implement projects which will help build the foundations for lasting island-wide relationships. The focus is on multicultural education and youth empowerment.

Moral power

Cypriot society acknowledges the liberal values promoted by the US, but at the same time it is very much in favour of following European values. The European Union also promotes liberal values not just within the union but to the rest of the world. As Cyprus is part of the EU, Cypriots believe that they are more involved in the promotion of such values. According to the 2016 US Global Leadership Report conducted by Gallup, 30 percent of Cypriots approve of US leadership, with 37 percent disapproving, and 33 percent uncertain.

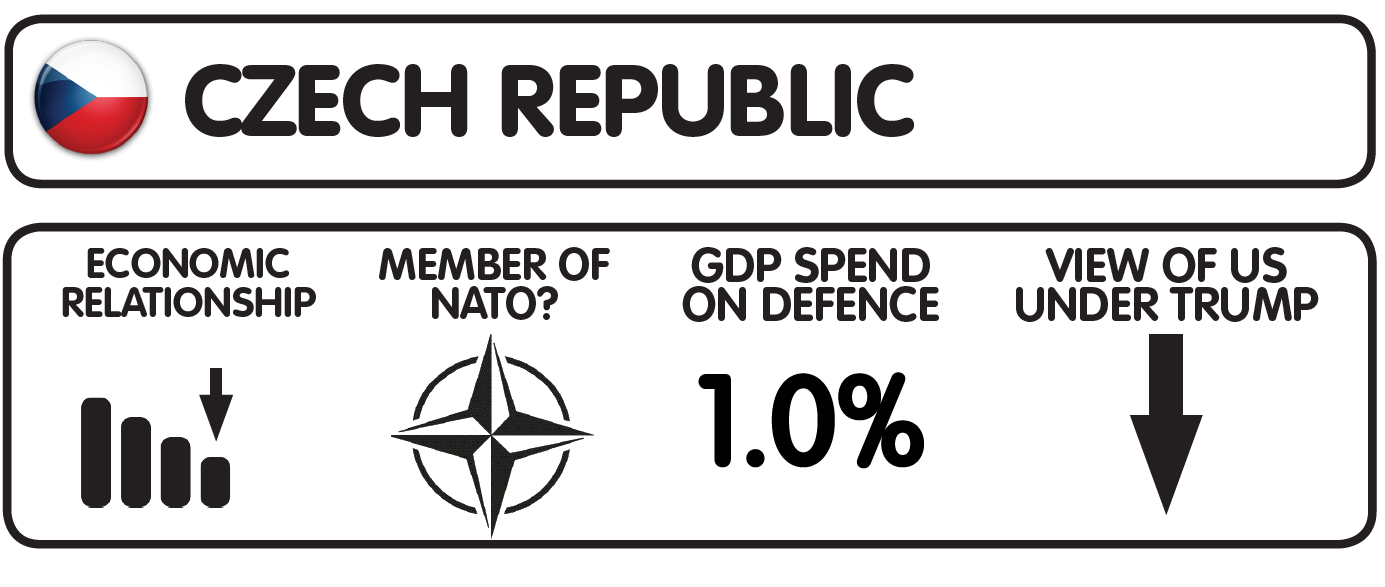

Economic power

The United States is a minor trade and investment partner for the Czech Republic. In 2015, the Czech Republic ranked in 26th place for the US, and the US was in turn the 12th most important trading partner for the Czech Republic. The main sectors in trade are the aviation industry, particularly jet engines, the automotive industry, and pharmaceutical products. The government would like to see more cooperation with the US, especially in sectors of the economy with higher added value, such as research and development. On the other hand, the Czech-US bilateral investment protection treaty is considered to be unfavourable. The government was particularly interested in the ‘investment’ part of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. It had hoped this would be a good alternative to a less favourable trade and investment treaty that the Czech Republic signed with the US at the beginning of the 1990s.

Security power

The Czech Republic sees NATO as the main guarantor of its national security. The crucial position of the US within NATO is seen as a principal mechanism through which that country assures Czech national security. The deployment of American troops to Europe, something which is continuing under the new administration, also increases Czech security. The government had been worried about statements from Donald Trump on NATO, but it hopes that the pro-NATO stance of professionals in the administration will prevail. That said, the US has little direct impact on Czech national policy. The last time such impact was visible was between 2006-9, when the US planned to place part of its missile defence in the Czech Republic, which led to a very mixed reaction in the country.

Cultural power

In the decade after the Velvet Revolution in 1989, the US exerted a strong social and cultural influence on the Czech Republic. The Czech people looked up to the US as a model of a free and democratic society. The US still has a large cultural impact through cinema, music, and social media. However, its influence as a model is diminishing – the Czech social model, with its emphasis on solidarity, is very different from that of the US. Major American IT companies are active in the Czech Republic, and there has been a backlash against Über. The largest commercial television company in the country is owned by company whose major shareholder is Time Warner.

Moral power

Former president Vaclav Havel was consistent in promoting the US as a moral leader and symbol of liberal values in the world. He had such a large influence on Czech foreign policy that for many years it remained strongly value-orientated, with democracy promotion as one of its main priorities. However, Havel’s legacy has faded and the country now behaves more and more like a pragmatic trade-orientated country. At the same time, by the end of the George W Bush presidency the image of the US had deteriorated. While journalists and other opinion-formers reject Donald Trump, a recent poll showed support in the country for the president’s latest positions, including 62 percent support for closing the border to refugees. The image of the US in the Czech Republic remains little changed overall.

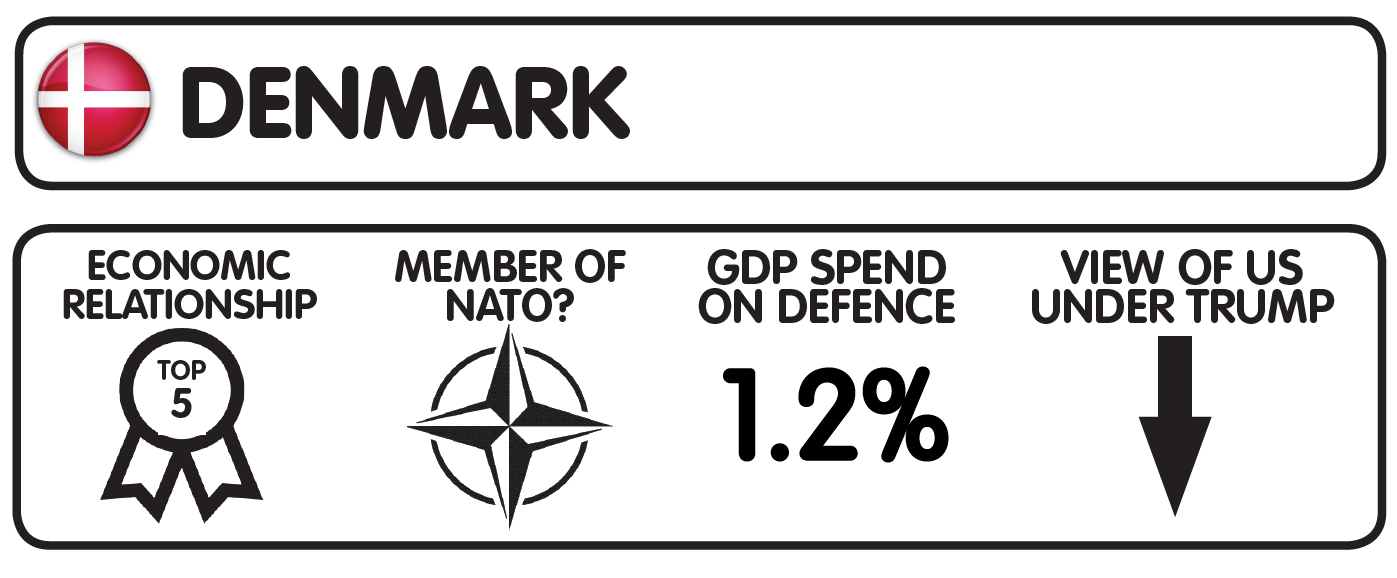

Economic power

The economic relationship with the United States is crucial for Denmark. The US is Denmark’s largest non-European trading partner, and its fourth largest export market. In 2015, 2,750 Danish companies exported to the US, and 650 Danish companies own subsidiary companies in the US, employing around 65,000 people. In turn, the US has around 550 subsidiary companies in Denmark which employ around 39,000 people. Key for Denmark is the climate change sector, which Denmark has devoted significant time and resources to in recent years. This will be more difficult under the Trump administration. Denmark also worked very actively towards the adoption of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership agreement, which was a main economic interest in the relationship with the US.

Security power

Danish willingness to follow the US line on security matters, including active participation in US or NATO interventions, has meant that Denmark has evolved from being part of a large group of valued European allies to being part of a smaller group which benefits from a special flow of information. It has gained unprecedented access to American decision-makers. The expectation in Denmark is that US support for NATO will remain. But, since the election of Donald Trump, the Danish prime minister and defence minister have emphasised the need for Denmark to increase defence spending. A wide range of Danish politicians and commentators have also argued that, in the wake of the US presidential election, Denmark should form new alliances on security within the EU.

Cultural power

American culture – and particularly popular culture, from jazz, rock, and rap to television shows and literature – has had a longstanding impact on Danish culture. This has not changed in the past ten years. The number of American expatriates in Denmark is not particularly high, which also means that they have not played much of a direct role in domestic politics or the economy. US companies became involved when state-owned IT companies in Denmark were privatised. As a consequence the backbone of Danish IT infrastructure has been developed and managed by American companies. In 2015-16, the US was the number one destination for Danish tourism outside of Europe.

Moral power

Generally, a majority of political parties, as well as the Danish public, has considered the US to be a moral leader with the ability as well as the responsibility to promote liberal values in the world. Since the end of the cold war, Denmark has participated actively in all major US military interventions, including Iraq, Afghanistan, and the anti-Islamic State group coalition in Iraq and Syria. While there was distinct unhappiness among the public about the Iraq war in 2003, the long-term fallout of this was limited. A poll by Megafon and TV2 in February 2017 showed that a majority of the Danish public believe the Trump presidency poses a direct threat to national security. Fifty-nine percent said the Trump presidency was the biggest fear they had, followed, at a distance, by terrorism and Russia.

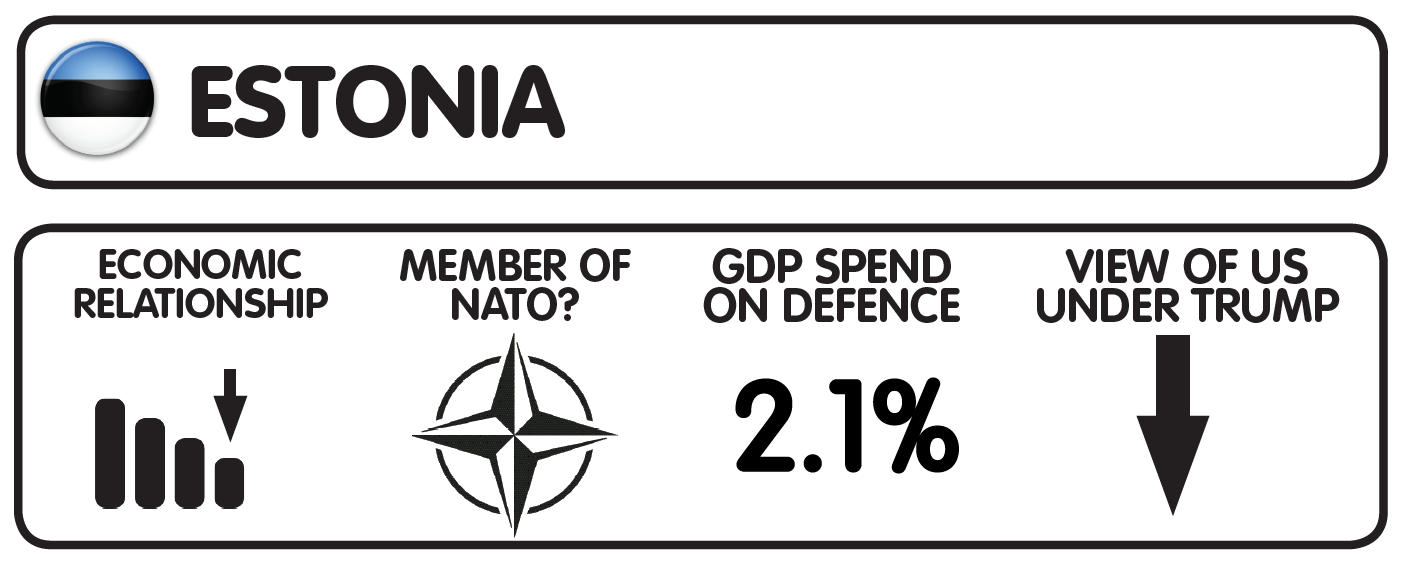

Economic power

The United States does not sit among Estonia’s top ten trade partners. However, Estonia does see the US as an important partner in the field of high technology (such as IT and biotechnology), and it views the US as a major source of new technologies and venture capital. After US investments in the national railway and national energy services were rejected in the period of privatisation in the 1990s, the level of US investment in Estonia remained relatively low. One sizeable investment is that made by Molycorp to the local fertiliser company Silmet. In terms of economic freedom and the free market, there is great support among Estonians for the leading role the US plays in the global economy.

Security power

From Estonia’s perspective, the main component of deterrence against Russia is the US military presence in the form of: ground forces; the ground attack aircraft A10; the mid-range air-defence system used to protect the ground force base in Tapa; and the air force base in Ämari. During the Obama presidency, the US also contributed financially to developing military infrastructure for US troops to use. Thanks to this, Estonians value the US contribution to the provision of security in Estonia even more than previously. The Estonian government hopes that the US will continue to uphold NATO and bilateral security cooperation with Estonia. Estonia fulfils the NATO criterion of defence expenditure running at 2 percent of GDP.

Cultural power

Before the restoration of Estonia’s independence, the US symbolised the ideals of freedom and democracy, against the backdrop of the overregulated and autocratic society in the Soviet Union. At that time, Estonians also enjoyed relatively close contacts with the Estonian diaspora in the US and Canada, who fled there following the Soviet occupation of Estonia in the 1940s. Over the last 25 years, the US has often been held up as a positive example in terms of the rule of law. The US now has an important social and cultural impact on Estonia through the spread of US mass culture and social media, such as Facebook, and Twitter, and YouTube.

Moral power

Estonian business, particularly in sectors related to free trade and innovation, still considers the US an important example to emulate. Since regaining its independence, Estonia has mainly pursued the US model of free trade and a free market economy. This approach has also somewhat spilled over into how Estonian society is arranged. For example, people are personally responsible for their education (particularly at university level), careers, and professional success. Doubts around the death penalty, Guantanamo Bay, and the US position on the International Criminal Court have somewhat reduced American moral authority. However, Estonians still consider the US the main moral cornerstone in today’s world and a security guarantor in the international arena.

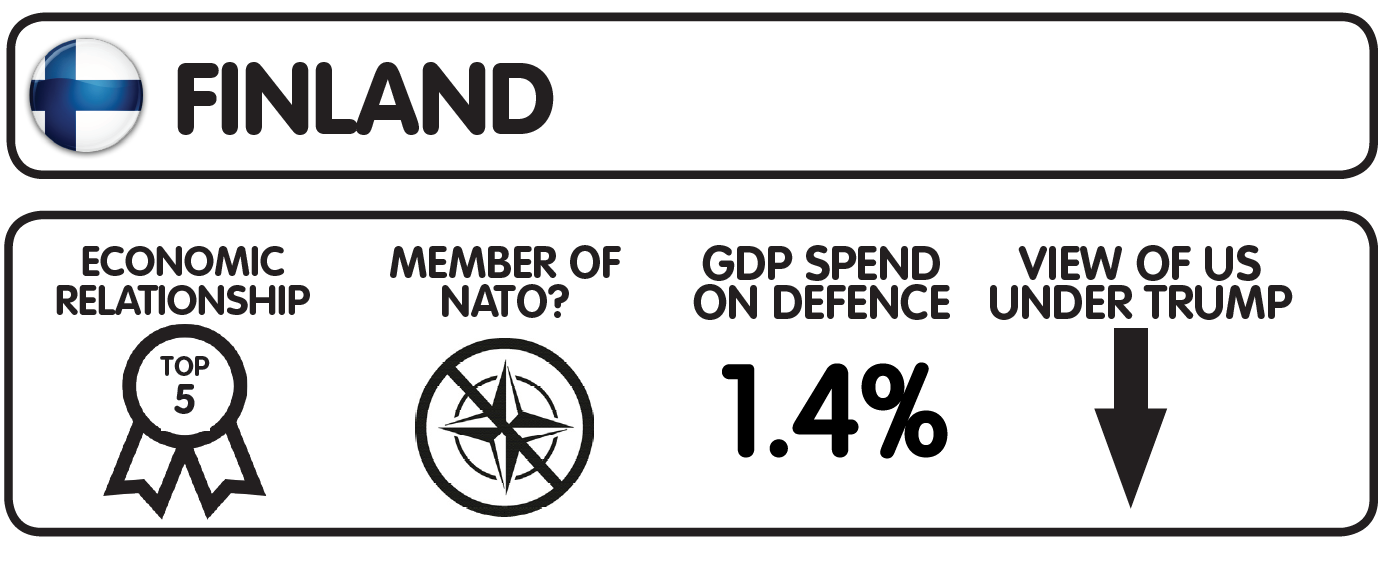

Economic power

Finland’s most important partners in terms of the economy, trade, and investment are all members of the European Union. However, among non-EU countries, the United States’ economic importance is underlined by its role as Finland’s third biggest export market and by Finland’s large trade surplus with it. Exports from Finland to the US consist above all of paper and paperboard, industrial machinery and motors, instruments and meters, electric machinery and equipment, chemical products, and refined petroleum products. Imports from the US to Finland include machinery, transport equipment, and telecommunications equipment.

Security power

Although Finland is not a member of NATO, the current Finnish government – like its predecessors – considers the US commitment to NATO and its continuing military presence in Europe to be crucial for Finland’s and Europe’s security. Finns do not view the EU as a real alternative in this sphere. In this sense, Finland was as concerned about Donald Trump’s ambiguous, or even critical, remarks about NATO as many NATO member states were. Key areas of cooperation between Finland and the US include

counter-terrorism and intelligence cooperation. The US is Finland’s most important bilateral partner when it comes to the arms trade, as it sold to it most of Finland’s pivotal defence equipment.

Cultural power

A decades-long theme in Finnish debates is that Finland is ‘Europe’s most Americanised country’. US influence is most notable in popular culture, with Finnish television channels buying in a substantial share of their content from the US. American movies dominate at the cinema. At the same time, Finns do not encounter many Americans in their country: Swedes, Russians, Germans, Britons, Chinese, and Japanese are ranked before Americans when it comes to tourism.

Moral power

Finns have traditionally viewed the US as the embodiment of ‘the West’ and a beacon of free trade. At the same time, the Finnish population has a deep-seated suspicion of ‘great power politics’. Finns are especially negative about the US under Trump: according to survey data collected by the Finnish Business and Policy Forum in early 2017, only 1 percent of Finns fully agree and 10 percent partially agree with the statement that ‘the US acts correctly in international politics and deserves the support of Finns. The survey data also showed that 66 per cent believe that the number of wars and conflicts in the world will increase as a result of the new administration.

Economic power

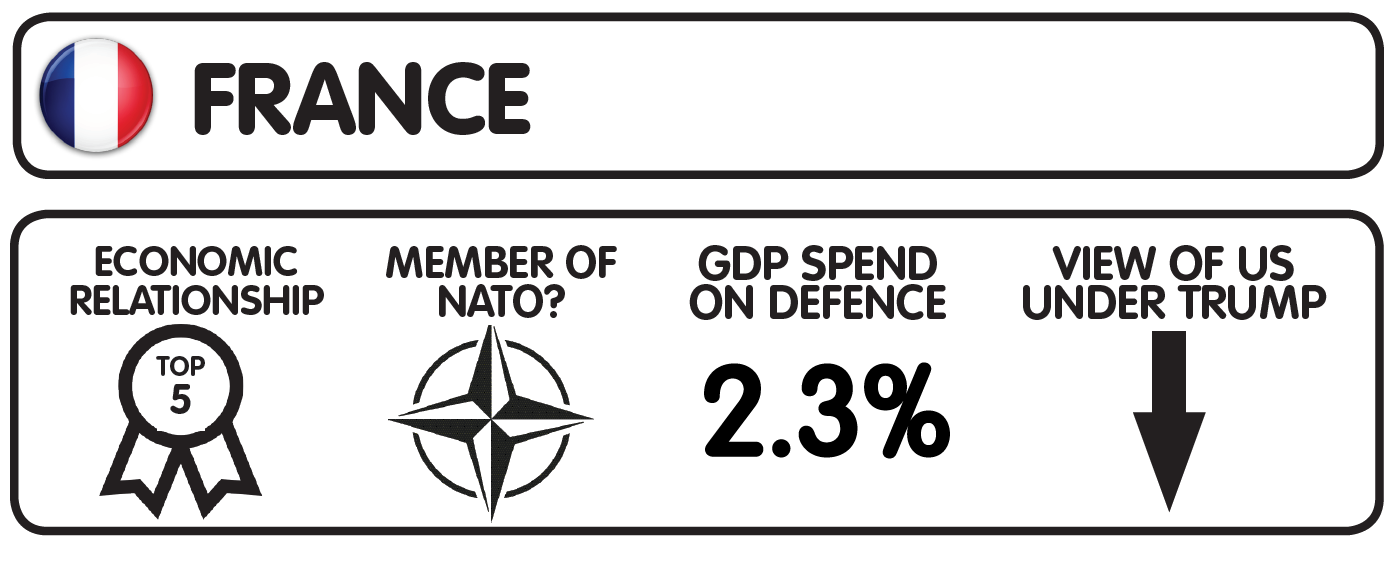

Trade and investment in research and development are key dimensions of the Franco-American relationship. They are often underestimated in France, where the media focuses primarily on foreign and security policy cooperation. The United States is France’s second biggest trade partner, and exports to the US market are vital for French industry. This cooperation pertains mainly to luxury products and transport equipment, machinery, chemicals, and pharmaceutical products. Another dimension of the economic relationship concerns extensive research and intellectual exchanges. France is the fourth most common destination for Americans studying abroad, with more than 800 inter-university agreements in operation and 17,000 American students welcomed each year. The US is France’s leading scientific partner: together they produced over 12,000 co-publications in 2012, representing more than a quarter of French international co-publications.

Security power

The consensus remains that the US is an indispensable partner in European security. France is less directly affected by a potential weakening of US support to NATO, but the French government expects that the Trump administration will not review its commitment to guaranteeing European security. The US will continue to help France’s national security by: supporting the military mission in the Sahel region financially and logistically; sharing intelligence and know-how in the fight against terrorist cells in Europe; and leading the coalition against the Islamic State group. For the French government, NATO and European defence are not mutually exclusive, and it feels that France should invest more in its defence in order to strengthen its national strategic autonomy, reinforce NATO, and develop a more credible European defence outside the NATO framework.

Cultural power

After difficult years during the George W Bush administration in which underlying anti-American sentiment hardened, Barack Obama’s remarkable popularity in France led to a ‘golden era’ for US cultural impact in the country. This cultural impact is primarily centred on the movie and music industries. Sport, on the other hand, has lost the influence it previously had between the 1970s and the 1990s. In the past 15 years, proficiency in English has improved dramatically, and the use of English terms in the French language continues to grow. Activist movements, especially in the suburbs of major French cities, have drawn inspiration from American civil society movements such as Black Lives Matter.

Moral power