The Marib paradox: How one province succeeds in the midst of Yemen’s war

Summary

- The province of Marib in Yemen has undergone a remarkable transformation, from a place of conflict to beacon of relative stability even while the war continues in Yemen, including not far from Marib.

- Central to this improvement is the leadership shown by the province’s governor, Sheikh Sultan al-Arada, who has taken advantage of the decentralisation drive that was supposed to form part of Yemen’s post-uprising transition but which has recorded only patchy success.

- Marib’s newly acquired autonomy has allowed it to retain a share of its natural resource wealth, improve infrastructure, and expand government services, including paying state employees regularly and supporting a functioning judicial system.

- Decentralisation processes which are locally led in this way represent a core lesson for international players interested in extending stability and peace across Yemen.

- Europeans should work to bolster stabilisation in Marib while applying its lessons elsewhere in Yemen, at all times linking their efforts to those of the UN while collaborating with regional and international partners.

Introduction

If you lived in Marib – and had survived the recent conflict that rolled across it – you would have stood witness to one of Yemen’s most troubled provinces transforming into arguably its most stable. Not only that, you might even agree that today Marib is thriving. Construction is everywhere in Marib city. A new football stadium, boasting German turf and built to FIFA standards, is rising from the ground. Businesses from across Yemen are moving here. A new independent university is welcoming 5,000 students and has plans to expand further.

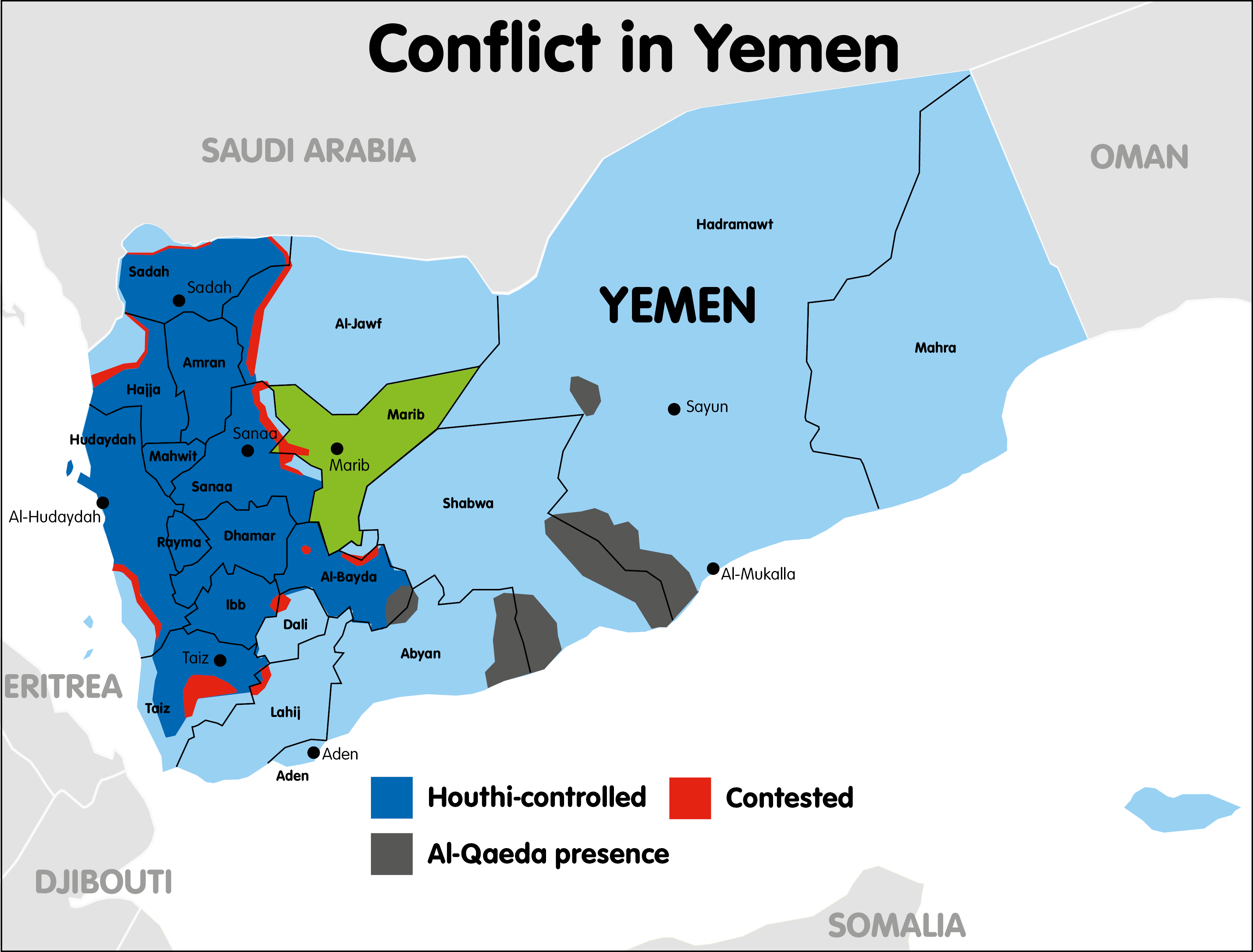

Some of the fiercest fighting in the recent conflict took place in Marib – and continues to take place in the province’s western district of Sirwah – but Houthi-allied forces retreated from the provincial capital and other key areas in 2015. In the ensuing period, local authorities, with the aid of key regional powers, most notably Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, succeeded in restoring relative stability. Once one of Yemen’s most restive provinces, Marib has emerged as a new economic and socio-political centre, something unprecedented in its recent history. After centuries of marginalisation, many Maribis will triumphantly tell you, it has regained a slice of its historical importance: Marib was once the seat of the Sabaean empire, one of pre-Islamic Arabia’s most powerful and advanced urban centres.

The wounds of war linger still. Damage from the fighting is visible on many of the city’s buildings, while the main hospital remains filled with patients who have lost limbs, whether from the fighting itself or from landmines left by the Houthis and their allies. And on the border between Marib province and Yemen’s capital Sanaa, the bloodshed continues.

Nevertheless, something has gone right for Marib in the way that it has not for provinces elsewhere in Yemen. Some things are unique to Marib, like its natural resource wealth, stable local power structures, and effectively driven support from international actors belonging to the Saudi-led coalition, including, most notably, Saudi Arabia itself. That being said, Marib’s experience holds wider lessons for Yemen’s future: embracing decentralisation, empowering local actors, and focusing on ground-up stabilisation are all strands of the story that international and local players interested in bringing peace and stability to Yemen should note.

The legacy of war

In 2011, Yemen experienced an extended anti-government uprising. Sparked by protest movements that unseated long-time leaders in Tunisia and Egypt, the uprising came amid building instability in Yemen, which had witnessed insurgencies across the country along with deepening tensions inside its political and security establishment. Initial scattered protests eventually coalesced into nearly year-long demonstrations against President Ali Abdullah Saleh, pulling in independent youth activists previously uninvolved in partisan politics, backers of the Houthis, Yemen’s establishment opposition, defectors from Saleh’s General People’s Congress party (GPC), and backers of a return to autonomy in the formerly independent south. But the movement was riven with fractures and historical tensions between its components beyond the shared aim of bringing about the fall of Saleh.

These tensions only deepened in the wake of the signing of a deal mediated by the Gulf Cooperation Council and backed by the United Nations. This was an agreement to transfer power between the GPC and the establishment opposition parties and which saw Saleh cede power to his long-time deputy, Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who was to preside over a two-year transition. Despite efforts to incorporate parties outside of the agreement into the mainstream political process – most notably through the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) process set up as part of the power-transfer agreement – events outside the transitional period soon overtook the wider transitional process. In the south – an independent state until 1990 – dissatisfaction with what was seen as a Sanaa-centred process led to open support for secession. Meanwhile, in the north, even while the NDC continued, the Houthis engaged in a continuing series of battles with their tribal and military rivals, inching close to Sanaa before finally seizing military control of the capital in autumn 2014.

As the Houthis consolidated power, they eventually ousted Hadi. After Hadi fled house arrest and rescinded his resignation, the Houthis and their allies – military backers of former president Saleh – took the fight to Hadi’s new base in Aden, using the Yemeni air force to bomb his position and forcing him to leave the country. This – in addition to the Houthis’ decision to carry out military exercises along the Saudi border and sign an agreement for direct Sanaa-Tehran flights, among other issues – prompted the Saudi-led coalition to launch a military intervention in Yemen. While the Houthis have been dislodged from much of the territory they initially took, they maintain control of Sanaa and the internationally recognised president – and most of the cabinet – has not yet returned to Yemen.

The resilience and capability of state institutions varies considerably across the country. In areas of Houthi control, state institutions have largely remained but have been weakened by both the financial crisis and the growing strength of parallel institutions set up by the Houthis. Meanwhile, the liberation of key areas from the Houthis and al-Qaeda – most notably, the former southern capital of Aden – has not led to a flourishing of peace and stability. On the contrary, many places have become fields of tension and conflict between Emirati-allied secessionist forces and elements of the internationally recognised government.

A central plank of Yemen’s post-Arab uprisings transitional process was a move to a federal system of governance. Analysts and diplomats alike – both within the international community and within Yemen itself – had often drawn a link between the country’s historically centralised system of governance and its deep corruption, uneven security situation, and internal tensions: following pro-unity forces’ victory in the 1994 civil war, centralising amendments to the constitution and Saleh’s concentration of power in the hands of a tight circle of allies led to a vast system of patronage that binds in key tribal and political figures. This, in turn, fuelled deepening resentments among many Yemenis, who saw the new class growing wealthy as the nation remained poor and, particularly outside Sanaa, underdeveloped. This was particularly true in provinces such as Marib, Hadramawt, and Shabwa which remained impoverished and suffered from weak infrastructure.

After the 2011 uprising once-taboo discussions about federalism resurged, with many international (particularly Western) organisations and diplomats openly pushing for a shift to federalism. Many Yemenis had previously regarded talk of federalism as tantamount to paving the way for the dissolution of the country. Eventually, however, the internationally backed NDC ended with a decision to establish a federal system.

The new federal system was controversial from the start. While NDC delegates endorsed a federal system, they failed to agree on the number and nature of the federal divisions. In response, they authorised Hadi to appoint a special committee to decide the issue, which promptly reached a decision to split the country’s provinces into six super-provincial federal divisions. Even at the time, many observers took issue with the way the agreement was reached, arguing that it was pushed through by Hadi in an undemocratic fashion.[1] Others took issue with the way the country was divided: Yemeni analysts criticised the collection of most of the country’s Zaidi Shia-majority provinces into a single, resource-poor region lacking a port as a potential invitation to conflict. They criticised the starkly unequal population totals of different regions: both the Yemeni Socialist Party and much of the secessionist Southern Movement condemned the division of the formerly independent south into two regions. Others, harbouring a long-standing suspicion of federalism, cast it as part of a nefarious plot to divide and weaken the country.

That being said, in many parts of the country the new system was seen as a potential means for more equitable governance. This was particularly true in the new “Saba” region, which was made up of the provinces of al-Bayda, al-Jawf – and Marib. Activists and local officials in Marib saw the new situation as a means of finally gaining a mechanism for benefitting from the impoverished province’s resource wealth, which historically went to the central government.[2] Initially, this enthusiasm manifested itself in a variety of ways. Politically active youth from Marib and nearby provinces – many of whom were energised by their participation in the 2011 uprising – assembled pressure groups, something that was paralleled by movements led by civil society and political groups.[3] They aimed to transfer the new energy in the capital to the provinces, seeing the new federal system as a means of achieving long-held aspirations for greater development and democratisation, building on nascent civil society activity predating Saleh’s removal from power.

However, the process largely stagnated after the NDC ended. The transitional period overran its theoretical two-year duration and dissatisfaction grew with the economic situation and the deepening power struggle in the country’s north. Regardless of great expectations, the new federal system failed to move significantly from paper to the ground. Much of the rhetoric on the matter has had a counterproductive effect, deepening pre-existing anxiety over federalism and ultimately missing an opportunity to draw attention to the ways that the country as a whole can benefit from shifting to a more functional and locally driven decentralised governance system.

Enter Arada

As much of the rest of the country has been embroiled in conflict, Marib stands out as the one place where decentralisation has had some success.

Some history: with the discovery of oil in the 1980s and the opening of Marib refinery in 1986, the province acquired a new importance. But while the extraction of Marib’s oil and gas reserves grew to provide a significant proportion of the central government’s revenue, the province itself saw little of the benefit. As a result, Marib remained impoverished and undeveloped while government institutions were too weak to effectively funnel any of this wealth back to it. And, all the while, the province grew in infamy, as a security vacuum emerged which facilitated banditry and the spread of extremist groups like al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

In the wake of the 2011 uprising, figures in Marib seized on the evolving political situation to press for change in the province. Among them was its current governor, Sheikh Sultan al-Arada. A former member of parliament and member of a prominent family from Marib’s Wadi Abida tribe, Arada was appointed governor of Marib by Hadi in 2012 having spent nearly a decade relatively absent from formal politics after breaking with former president Saleh.[4] Arada was not just a native of the province but has long been based in Marib, rather than Sanaa, something that has helped him build legitimacy on the ground through his skill in resolving tribal disputes. His grounding within Marib’s tribal system granted him local legitimacy. This has allowed him to present himself as close to his constituents – in contrast both to other local notables, who previously spent much of their time in the capital, and to officials of the current internationally recognised government, who have been largely based abroad.[5]

Following the Houthis’ takeover of Sanaa in September 2014, Arada emerged as a leader of efforts to prevent them from seizing Marib. This was in line with the anti-Houthi stance of key elites in the province. Most key figures in Marib opposed – and, indeed, fought – Houthi attempts to expand there. These elites include historic allies of Saleh, such as Sheikh Abdulwahid al-Qibli Nimran, the head of the Marib branch of Saleh’s party.[6] This military role only grew in the wake of a Saudi-led coalition’s launch of Operation Decisive Storm in March 2015, as Arada became a key figure in aiding and facilitating the military effort against the Houthis, drawing on his military background and deep knowledge of the tribal and societal fabric in the province.

Another reason for his recent success is that, in contrast to many other leaders in the fight against the Houthis, Arada opted to decisively plunge himself into governing following the liberation of most of Marib province from the Houthis in 2015. While others withdrew from the scene, continued the fight elsewhere, or fell prey to political manoeuvring, Arada instead recommitted to his vision as governor. Since then his key focus has been not just on restoring stability, but also on restructuring Marib’s historically fraught relationship with the central government: taking advantage of the government in exile’s relative distance, he has aimed to secure a level of autonomy within a provisional government, in addition to pushing forward a financial decentralisation plan that has guaranteed his government a direct share of the province’s natural resources wealth.[7] This has been facilitated by the implementation of decentralisation measures in line with those introduced under the NDC. More idiosyncratically, these advances are possible because of the current conflict. With most of Yemen’s urban centres either occupied by the Houthis or mired in political or military conflict, Marib has gone from being a marginalised town to an important urban centre.

Arada’s policies provide potential lessons for the rest of the country, particularly with regard to the shape Yemen will take after an eventual peace settlement. The reorganisation of the security forces has allowed for an unprecedented level of security in the city and even many rural areas. By bringing in more local leaders and forces, and pushing for greater accountability and transparency, current policies have increased trust in the security sector, while the governor’s efforts have seen a locally rooted force built in coordination with the government and interior ministry.[8] According to local officials, crime has fallen by 70 percent.[9] Simultaneously, in contrast to other areas in Yemen, Marib’s legal system was quickly reconstituted after the Houthis were pushed out, with judges’ salaries and personal security guaranteed.[10] This focus on transparent and legitimate local law and order capabilities is central to understanding the stability that has descended upon the province. The fruits of the changes are already evident.

At the same time securing a share of oil and gas revenues has helped to spur the expansion of government services, in addition to funding the payment of government employees.[11] Owing to an agreement made between the central government and Arada, Marib’s local administration has been able to keep 20 percent of its oil and gas revenues, rather than having to submit it all to the central government as it did before 2011.[12] This has been a huge factor in the province’s current prosperity, not simply due to the influx of money, but also due to the greater autonomy it has enabled: unsurprisingly, locally based officials have proven willing and able to engage in the development work that the province needs, including long-delayed improvements to Marib’s electricity, water, and transport infrastructure. This has also allowed it to be the only province to consistently pay its government employees. This, in turn, has helped to further build the economy, creating a more favourable environment for investors.

Crucially, the backbone of all of this has been trust-building measures. In contrast to the distance of many other officials in contemporary Yemen – many of whom are literally based outside the country – local officials in Marib regularly meet with representatives of political parties and tribal factions to try to reach consensus in decision-making, something that officials and activists in the province alike cast as a key factor in its current stability.[13] This has largely come from taking advantage of aspects of Marib’s pre-existing tribal system, rather than trying to force Marib’s political ecosystem into newly created structures.

This is not to say that Arada is not without detractors. Many members of the GPC party and other political parties have accused him of demonstrating favouritism to members of the Sunni Islamist Islah party, arguing that it has been the beneficiary of a disproportionate number of appointments.[14] Some tribal leaders from elsewhere in the province, while stressing their respect for the governor, have argued that he has demonstrated a bias towards his fellow Wadi Abida tribesmen, marginalising others in the province.[15] Regardless, his ability to maintain a critical mass of popular support – exhibited perhaps by the absence of the kind of wide-scale popular protests witnessed in other parts of Yemen – has undeniably aided his administrative efforts.

The international relationships that Arada and his administration have managed to develop are also crucial to the province’s success. Arada’s prominence in the fight against the Houthis and their allies allowed him to build upon his pre-existing relationships with key figures within Saudi Arabia and the UAE, both of which have long-standing historical ties to the tribes of Marib. This close cooperation has only deepened over time, particularly following the Saudi-led coalition’s decision to locate a base in Safer, to the east of the provincial capital, between Sanaa and Marib. This is no accident: located in the centre of the country, Marib is among Yemen’s most strategically located provinces, serving as the crossroads between: Saudi Arabia; key fronts in the neighbouring provinces of al-Bayda, al-Jawf, and Sanaa; and areas in the south from where the Houthis have already been expelled. For Arada and the coalition, this is a mutually beneficial arrangement: the Saudi-led coalition benefits from having Marib as a safe base of operation, while coalition support has helped him to increase the province’s stability.

Even after Arada shifted his focus from conflict to post-war governance, key military and political figures in both Saudi Arabia and UAE continued to maintain close ties with the governor despite his cordial relations with the Islah party, which is linked to the Muslim Brotherhood. This has not just facilitated aid, but, according to witnesses on the ground, this has also improved the allocation of aid: close coordination between local officials and Gulf donors has helped direct external, overwhelmingly Gulf, funding of key projects, ranging from the improvement of health facilities to the bolstering of local security forces. This has also given the province crucial leverage with the internationally recognised government, which remains riven with factional divisions. Because of his ties with key coalition leaders, Arada has been able to rise above the gridlock that often characterises relations with the Yemeni government.[16]

“Look to the way coalition countries deal with [Arada],” noted an official in the internationally recognised government, contrasting the governor with other officials in similar positions. “There’s a clear level of respect since they view him as a statesman – this has been key to Marib’s success.”[17]

In many regards, this trust has won Arada the space to devote much of his time to the task of governing – in addition to putting governance in a position where local forces are comparatively in the driver’s seat, particularly in contrast to many other parts of the country where the coalition has a more direct role.

In contrast to the factionalism of other areas of the country that the Houthis have been ejected from, Marib has largely coalesced around Arada. This is not to say that there are not tensions in some form, particularly with regard to allegations of an undue concentration of power in the hands of the Islah party and Arada’s tribal allies. Nonetheless, such tensions pale in comparison to those in cities, like Taiz and Aden, which have witnessed vicious infighting between anti-Houthi forces.

Conclusion and recommendations

While fighting continues in Sirwah, in the west of Marib province, the current conflict is distant enough that residents of the provincial capital have been able to decisively embrace a post-conflict scenario – and, crucially, one where rebuilding has been followed by marked urban expansion. In part, this is thanks to factors unique to the province. Marib city is the only major conurbation in northern Yemen completely out of Houthi control. In contrast to Aden – which the internationally recognised government of Yemen has declared Yemen’s temporary capital, but which is also a base for increasingly powerful southern secessionists – Marib does not suffer any regionalism-related tensions. This means that Riyadh-based government officials from the north are able to frequently make extended visits to Marib and move around with relative freedom there, although there have been several cases of extrajudicial detentions of Yemenis with alleged ties to the Houthis in the province. Trade – most notably in cooking gas produced in Marib – continues to cross conflict lines into Houthi-controlled territory, even as battles at the nearby fronts rage on. Buses from Sanaa and other areas under the control of the Houthis and their allies pass by regularly and largely without incident. This is despite the fact that the Houthis and the local administration in Marib remain bitter adversaries. Fighting continues on the Sirwah and Nihm fronts, while the Houthis occasionally launch rockets into the province.

All this is indicative of the extent to which Marib’s stability has solidified its nascent position as an economic centre. Almost perversely, much of its subsequent success has been driven by the troubles experienced by the rest of the country: the influx of economic activity and development would certainly have been far less substantial were it not for the influx of internally displaced persons, wealthy exiles, and cash.

That being said, Marib’s stabilisation is rooted in its capable and locally rooted leadership. The way in which it has made the most of the decentralisation that was meant to extend across the whole of Yemen has been central to this improved situation. Hosting significant natural resource wealth has been essential but direct financial benefit has come about precisely because of how the leadership negotiated the new federal system. All this has been complemented by strong backing from external players, namely Saudi Arabia, which has pursued a far more efficient approach than witnessed in other more dysfunctionally managed non-Houthi areas of the country.

As a result, there are three key lessons for other parts of Yemen and for international observers to draw.

The first is the importance of avoiding top-down decentralisation or stabilisation processes. Historically, the central government has been anxious about overly popular or charismatic locally rooted leaders, viewing them as a potential threat. Nonetheless, such leaders will be crucial to stability, particularly in light of the central government’s relative collapse after more than three years of conflict. In addition to identifying and empowering local leaders, stakeholders should bring these leaders into the wider political process to ensure this remains tied to a national dynamic. Without a national umbrella there is clearly a danger that too overt a localised track will feed succession tendencies and encourage fragmentation. In areas of the south where these sentiments are already intense, the genuinely autonomous model demonstrated by Marib may be one of the few ways of creating a framework that can still hold the country together in a unitary, albeit loose, fashion. This will require a delicate balancing act. But going local is now unavoidable if the country is to be stabilised. Critically, any future political deal should not try to reverse this trajectory with a new centralising drive in a manner that feeds new resentments and risks provoking further unravelling. Marib’s new autonomy is here to stay and should become a model for elsewhere rather than rolled back once the wider conflict dies down.

This represents a potential opening for Europe given its relatively neutral position in the conflict and key European actors’ pre-existing outreach to players currently outside of the political process, such as tribal figures, southern secessionists, youth, women, and civil society groups. This will be comparatively easy in Marib owing to Arada’s positive relations with the central government. European governments, working with the UN, could aim to advance this track by facilitating discussions between local leaders and key stakeholders while working to implement more decentralised aid and stabilisation programmes. Europeans can bring substantial expertise to the table on issues related to federalism and this should be channelled via the UN to facilitate current political efforts that can help secure a sustainable peace. There is a strong precedent for this: former National Democratic Institute Yemen head Robin Madrid’s work in Marib and neighbouring provinces in the early 2000s is still fondly remembered by local tribal leaders, who continue to express appreciation for her leadership in efforts to bolster civil society, local governance, and development.

The second lesson from Marib relates to the importance of locally owned and legitimate economic growth and the restoration of services in stabilising an area. Marib’s stabilisation led to its economic boom, in turn further stabilising the province and providing jobs for locals and new arrivals alike. Ultimately, this will be a key way of restoring peace: Yemen’s failed 2011-2014 transitional process showed that ignoring economic and quality-of-life grievances in service of higher-level political aims risks fuelling the wider delegitimisation of the political process among average Yemenis. Europeans and other key actors should therefore prioritise rapid post-conflict stabilisation efforts, service restoration, and the encouragement of economic growth across the country as soon as conditions allow. This will require far greater funding and focused local efforts than Europeans are currently engaging in, particularly in impoverished areas lacking local natural resources. But it is already possible to replicate this track in other parts of the country that have entered a period of stability, such as Hadramawt, Mahra, and Shabwa provinces. Europeans should immediately focus on stepped-up stabilisation efforts, whether directly through aid and investment or by facilitating it through infrastructure support. They should also encourage inclusive government and internal dialogue as well as reconciliation efforts. Marib’s gains may be significant, but, as long as conflict continues, they remain fragile and must be safeguarded.

The third lesson relates to the key potential role that the coalition can play in stabilisation: this presents a means of collaboration between Europe and the coalition – something that can build trust between the two parties that could be replicated elsewhere. Working in collaboration, Europe, the Saudis, and the Emiratis can reproduce the spirit of the Marib model in other parts of the country by empowering local leaders and decentralised governance structures. They should also make sure to link this to UN efforts, particularly with regard to using economic and development levers to advance national political negotiations. This is particularly true with regard to key avenues that all sides see as important, specifically in facilitating economic growth and development – even through actions as seemingly minor as microfinance programmes – and through capacity-building involving security forces, local administration, and government staffers. Here, Europeans and particularly the United Kingdom, given its close relationship with Riyadh, should press the coalition to truly internalise the lessons of Marib for wider implementation. It is no secret that the dysfunctionality and ill-fitting nature of international interventions in Yemen has often exacerbated the country’s problems. All key stakeholders in Yemen – including the UN, Europe, and the coalition – should learn the lessons of Marib. This will in part require Saudi Arabia to move its focus away from exiled politicians in Riyadh and towards those based on the ground.

In short, while Yemen remains in the throes of a deep economic crisis and a debilitating conflict, there remain bright spots of stabilisation, most notably in the province of Marib. While partially rooted in local factors, these places are nonetheless potential models for the country – something of which Yemen is in dire need.

About the author

Adam Baron is a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He focuses on the Middle East with an emphasis on Yemen and the wider Arabian Peninsula. His previous works for ECFR include ‘Yemen’s forgotten war: How Europe can lay the foundations for peace’. He is a co-founder of the Sanaa Center for Strategic Studies, a Yemen-focused research centre.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to a number of colleagues at ECFR for their help and support on this paper, particularly Julien Barnes-Dacey and Adam Harrison, in addition to the many people in Marib who have consistently made my research on and fieldwork in the province rewarding and fruitful.

Footnotes

[1] The six-region federal map was agreed upon by a subcommittee formed out of members of the National Dialogue Conference. It was rejected by representatives of the Houthis and the Socialist Party.

[2] Author interviews, local government officials Marib, November 2017.

[3] Author interviews, youth activists, Sanaa, March 2014.

[4] Author interviews, local government officials, Marib.

[5] Author interviews, Maribi tribesmen, Marib, November 2017.

[6] Author interviews, Maribi tribal leaders, Cairo, October 2017.

[7] Author interview, Marib, November 2017.

[8] Author interview, local official, Mary 2018

[9] Author interview, local official, Marib, November 2017.

[10] Author interview, Sultan al-Arada, Marib, November 2017.

[11] Author interview, Central Bank of Yemen official, March 2018.

[12] Author interview, Central Bank of Yemen official, March 2018.

[13] Author interview, Yemeni tribesmen, Marib, November 2017.

[14] Author interview, Yemeni tribal leader, Cairo, October 2017.

[15] Author interview, Yemeni tribal leader, Cairo, October 2017.

[16] Author interview, local government official, Marib, November 2017.

[17] Author interview, Yemeni official, Marib, November 2017.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.