Give the people what they want: Popular demand for a strong European foreign policy

Summary

- European voters believe that there is a growing case for a more coherent and effective EU foreign policy in a dangerous, competitive world.

- They want to see the European Union come of age as a geopolitical actor and chart its own course.

- But policymakers will have to earn the right to enhance the EU’s foreign policy power, by producing tangible results and heeding the messages voters have sent them.

- Most EU citizens believe that they are living in an EU in which they can no longer rely on the US security guarantee, and that the enlargement process should be halted.

- They believe that it is crucial to address existential challenges – such as climate change and migration – at the European level.

- The new leadership of the EU’s institutions should allow these political impulses to guide their approach to foreign affairs.

Introduction

European policymaking is forever on the cusp of improvement. Every five years, a newly appointed high representative for foreign affairs and security policy takes over, declaring that coherence is just around the corner. As Javier Solana advised his successor in the role in 2009: “our capacity to address the challenges has evolved over the past five years, and must continue to do so. We must strengthen our own coherence, through better institutional co-ordination and more strategic decision-making.”

A decade later, another Spaniard – Josep Borrell – is set to take up the mantle of high representative. He believes that the situation has become worse. In an exclusive interview with the European Council on Foreign Relations in May this year, Borrell likened the Foreign Affairs Council of the European Union to a “valley of tears” in which foreign ministers lament multiple crises around the world but remain incapable of decisive collective action. They believe that their domestic political constituencies require them to act as states first – and as part of a union only after this. The rise of nationalist and anti-system parties across the Western world in the past decade has reinforced this unspoken perception among EU governments – creating the risk that these governments will never truly fulfil their ambitions to establish a collective EU foreign policy.

Policymakers have endeavoured to work around this systemic handicap by creating a more flexible Europe – one that creates coalitions of willing states that pursue specific policy goals on behalf of the union. To some degree, this has produced results in foreign policy in the past ten years, including on the Kosovo-Serbia agreement and the Iran nuclear deal, as well as in other important areas of security and defence cooperation.

However, this approach has not overcome the fundamental impasse Borrell observed at the Foreign Affairs Council. This is due to the enduring perception that a genuine EU foreign policy would unsettle voters in member states. At the same time, many foreign policy issues have become increasingly politicised across the EU: in the run-up to national elections, many member states have engaged in genuine debates on the bloc’s approach to Russia and the transatlantic relationship.

But is this perception really accurate? The EU’s lack of foreign policy capacity – and, as a consequence, its feeble global standing – appears to largely result from the idea that the European population wants nothing else. Earlier this year, the European Council on Foreign Relations commissioned YouGov to carry out surveys covering more than 60,000 people across Europe. These included finding out their views on the foreign policy challenges the EU faces.

The study reveals a fundamental shift in Europeans’ views of the world. Although there is widespread public support for the idea of the EU becoming a cohesive global actor, there is also a growing divergence between the public and the foreign policy community on several key issues – ranging from trade and the transatlantic relationship to EU enlargement. Given this divergence, there is a risk that European voters could retract the foreign policy mandate they have offered the EU in the choices they made in recent European Parliament and national elections.

Voters want to know that their political leaders remain in control of the European project, and that it serves a clear purpose in crucial policy areas. Voters have not necessarily ruled out greater coordination between member states on EU foreign policy, but they are yet to be convinced of the case for this.

To make the case, European leaders will need to deliver results in foreign policy using existing forms of coordination between member states, and to respect the messages that voters send them. The public want the EU to be a responsible actor in a dangerous world. For them, the bloc should chart its own course between other actors in a highly competitive, multipolar environment, avoiding fights that are not of its making but standing up to other continent-sized powers and tackling crises that affect its interests. They want EU foreign policy to turn on the logic of Europe’s collective interests – not on the logic of European cooperation or integration for its own sake.

Therefore, the EU can only justify enlargement on the basis of the direct benefits it brings to citizens in current EU member states. Similarly, the bloc can only justify investment in EU – rather than NATO – defence capabilities if this demonstrably improves Europeans’ security.

Finally, voters want the EU to heed their fears about climate change and migration as major causes of insecurity – and to create a European-level response to these challenges. These messages should guide the EU leadership’s foreign policy in the next five years.

Cooperation in a dangerous world

Europeans feel unsettled. As a recent ECFR paper shows, European leaders need an inclusive, compelling story about the future based on a more emotional understanding of voters. This emotional connection will matter in elections, as European leaders seek to mobilise voters and persuade them to engage in the democratic process.

But it is just as important that the new leaders of the EU’s institutions fulfil their promises. Far from resting on their laurels following the unexpectedly high turnout in the European Parliament election (51 percent), these leaders should remember that, just before the vote took place, three-quarters of Europeans felt that either their national political system, the European political system, or both, were broken. Voters may have provided an open-ended mandate to deliver the “Europe of change” that features in the speeches of political leaders from the Greens to the parties of the newly formed, far-right Identity and Democracy group in the European Parliament. But, unless Europe creates emotionally resonant policies in the next five years, an electorate convinced that the political system is broken is unlikely to give the EU the benefit of the doubt a second time.

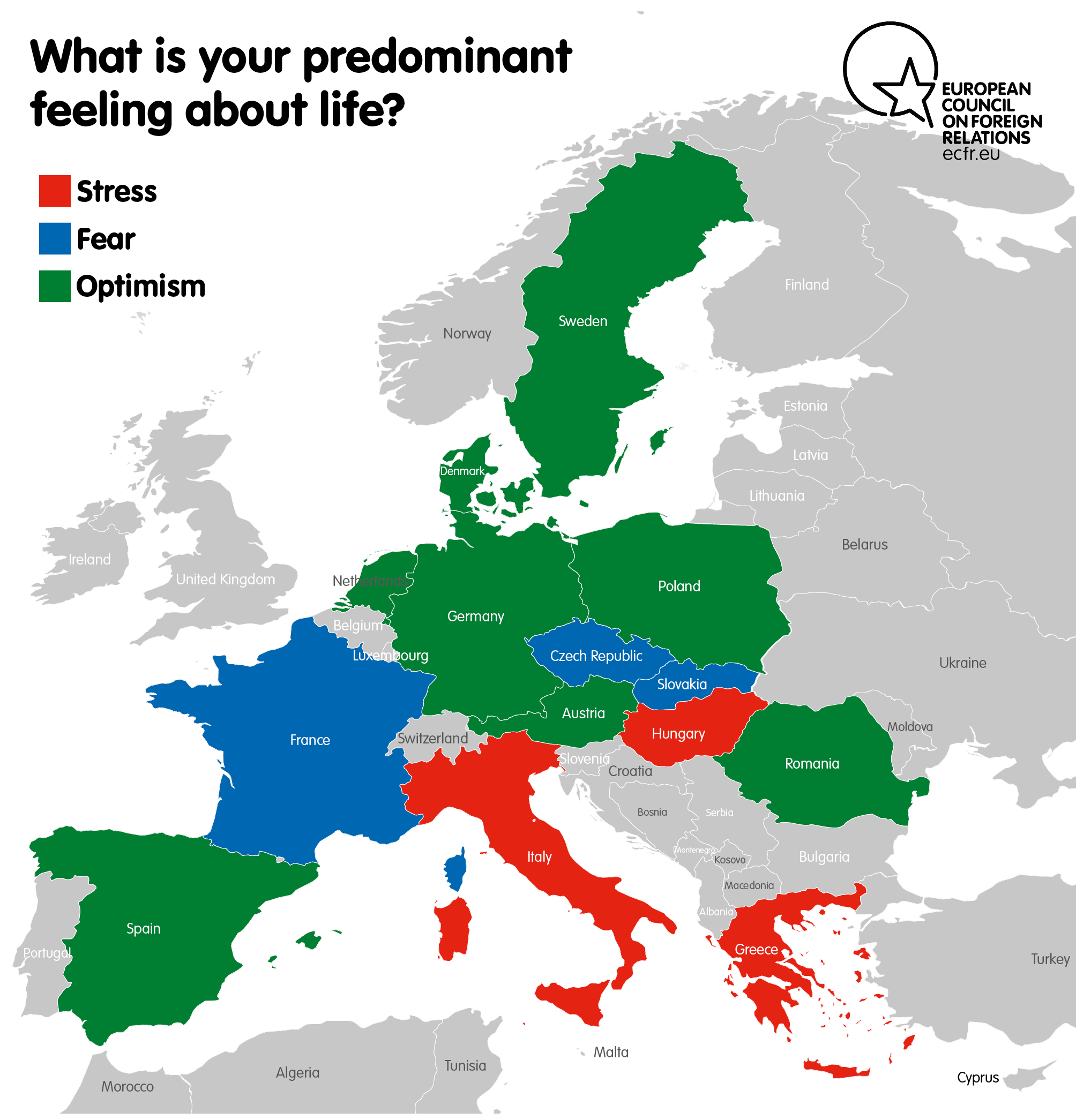

Foreign policy has a major role to play in the appealing vision of the future European leaders must create to reconnect with disenchanted voters. Europeans are living in what they perceive to be a dangerous world: the survey ECFR conducted earlier this year found that the top three emotions they describe as feeling were stress, fear, and optimism. The last of these emotions is crucial: they remain hopeful that Europe can meet their needs.

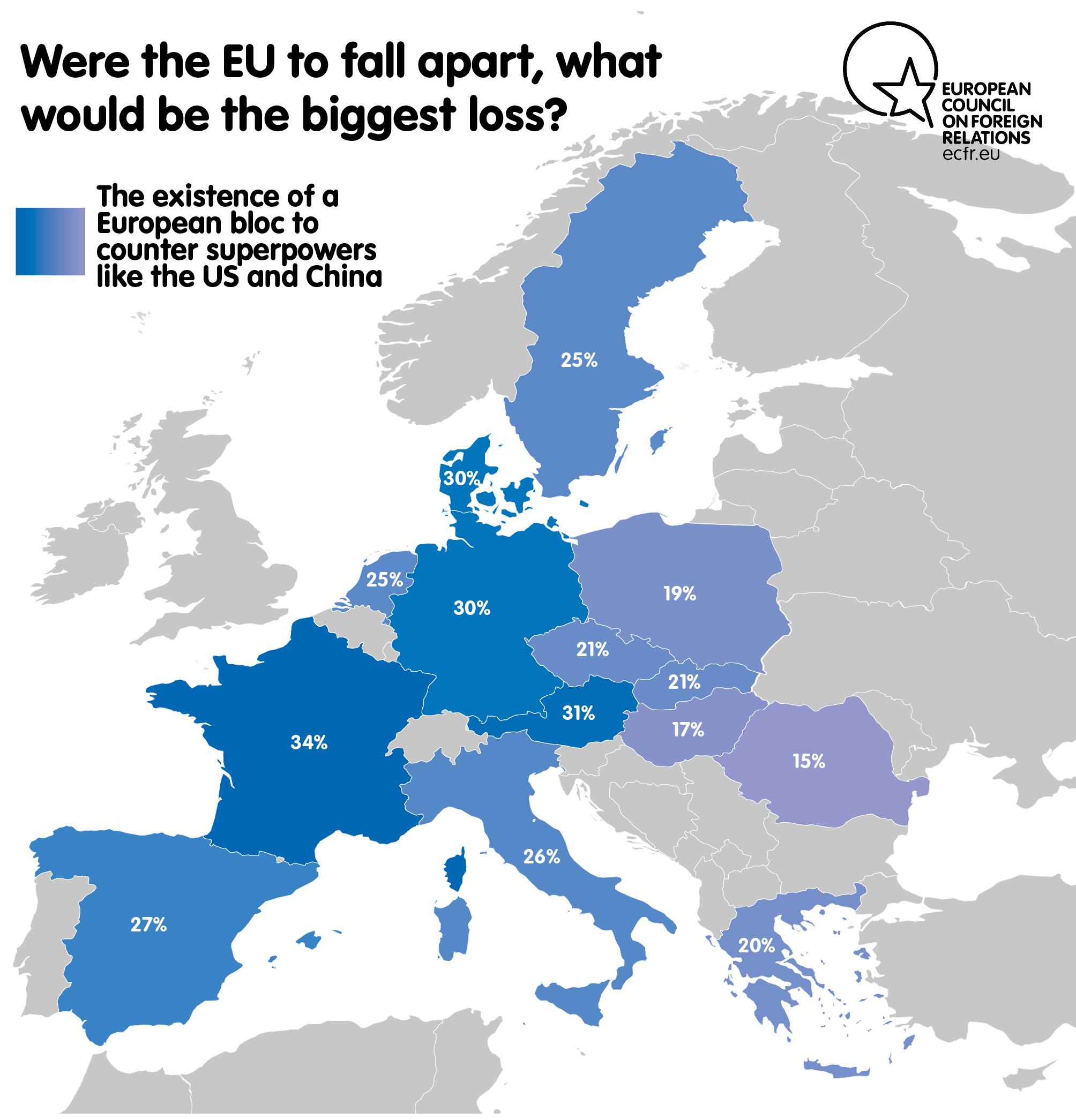

Along with concerns about the economy and inequality, the stress and fear that Europeans feel have deep roots in their perception of security threats. One-third of EU citizens believe that conflict between member states is possible. And, in every member state except Spain, more than 40 percent of them believe that it is possible that the EU could fall apart in the next 10-20 years. Voters believe that if the EU broke up tomorrow – following the collapse of the single market and the loss of the euro – the biggest loss would be European states’ ability to cooperate on security and defence, and to act as a continent-sized power in contests with global players such as China, Russia, and the United States.

Ursula von der Leyen, the new president of the European Commission, has recognised voters’ desire for the EU to become a strong, independent global actor that can set its own agenda: she has called for “a Europe that takes the global lead on the major challenges of our times”. But how exactly do European voters expect it to behave as a global actor? And do they accept that a more cohesive European foreign policy may, at times, mean placing the appearance of European cohesion above national strength on the international stage? ECFR’s survey suggests that there are three broad areas of consensus on the kind of EU that they would like to see emerge in international affairs.

A player big enough to avoid taking sides

Firstly, voters believe that, if the EU is to navigate the turbulent waters of geopolitical competition, it will need to act independently. The bloc should no longer rely on any one member state or leave itself at the mercy of an outside power. In this sense, voters are perhaps more forward-thinking than the European foreign policy elite, who talk of l’Europe qui protège – or say that “the era in which we could fully rely on others is over” – but remain fearful of taking the kinds of decisions that are the logical result of this approach.

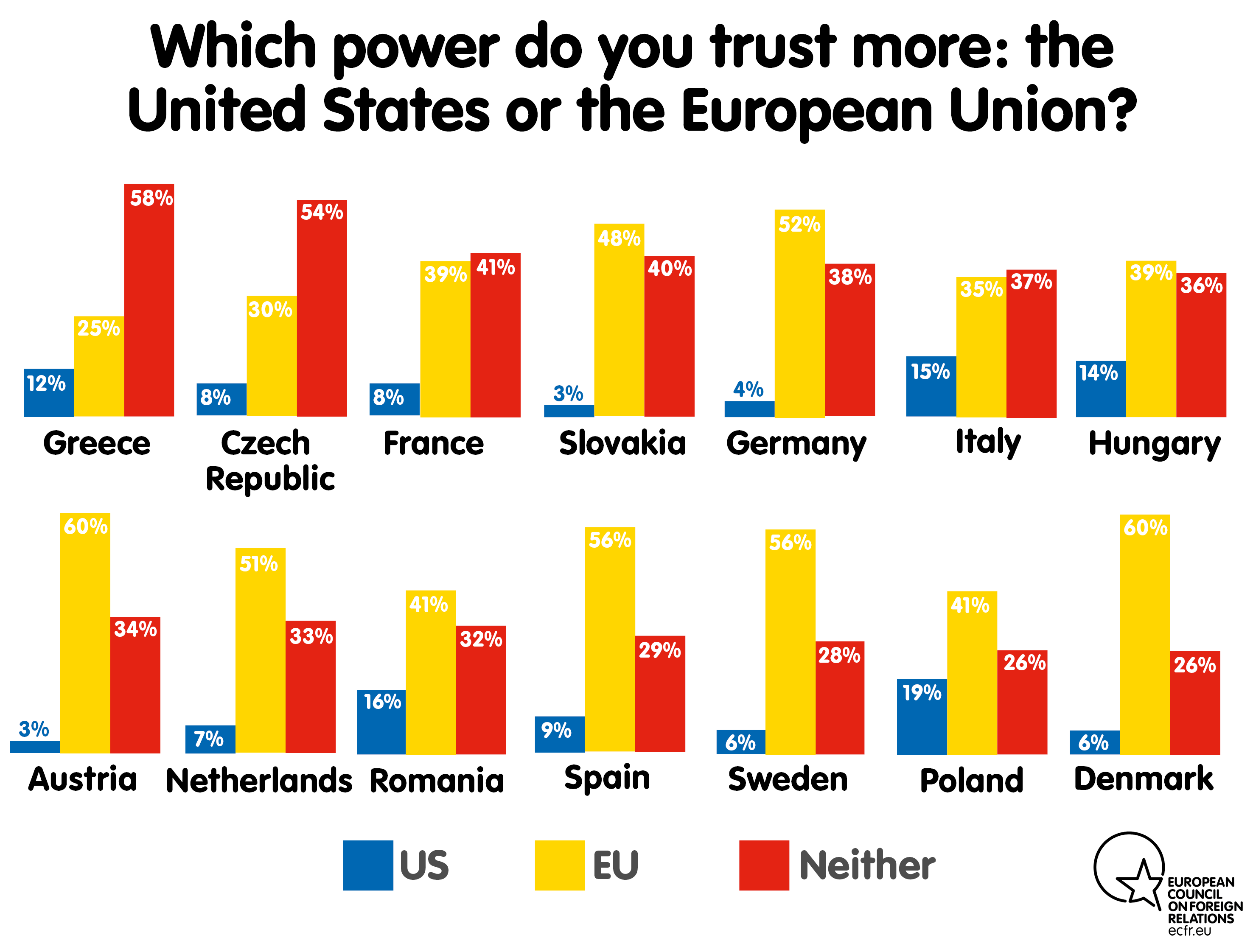

Three years into Donald Trump’s tenure as US president, European voters seem ready to face the harsh reality of global politics. ECFR’s survey shows that they no longer believe that the US can serve as the guarantor of their security. (This is despite the fact that, in most member states, large minorities of people believe that their own country has a special bilateral relationship with the US.) Overall, Europeans place more trust in the EU than national governments to protect their interests against other global powers – although, in numerous member states, many voters do not trust either the US or the EU (in Italy, this was the view of 36 percent of people; in the Czech Republic and Greece, it was the view of more than half of them).

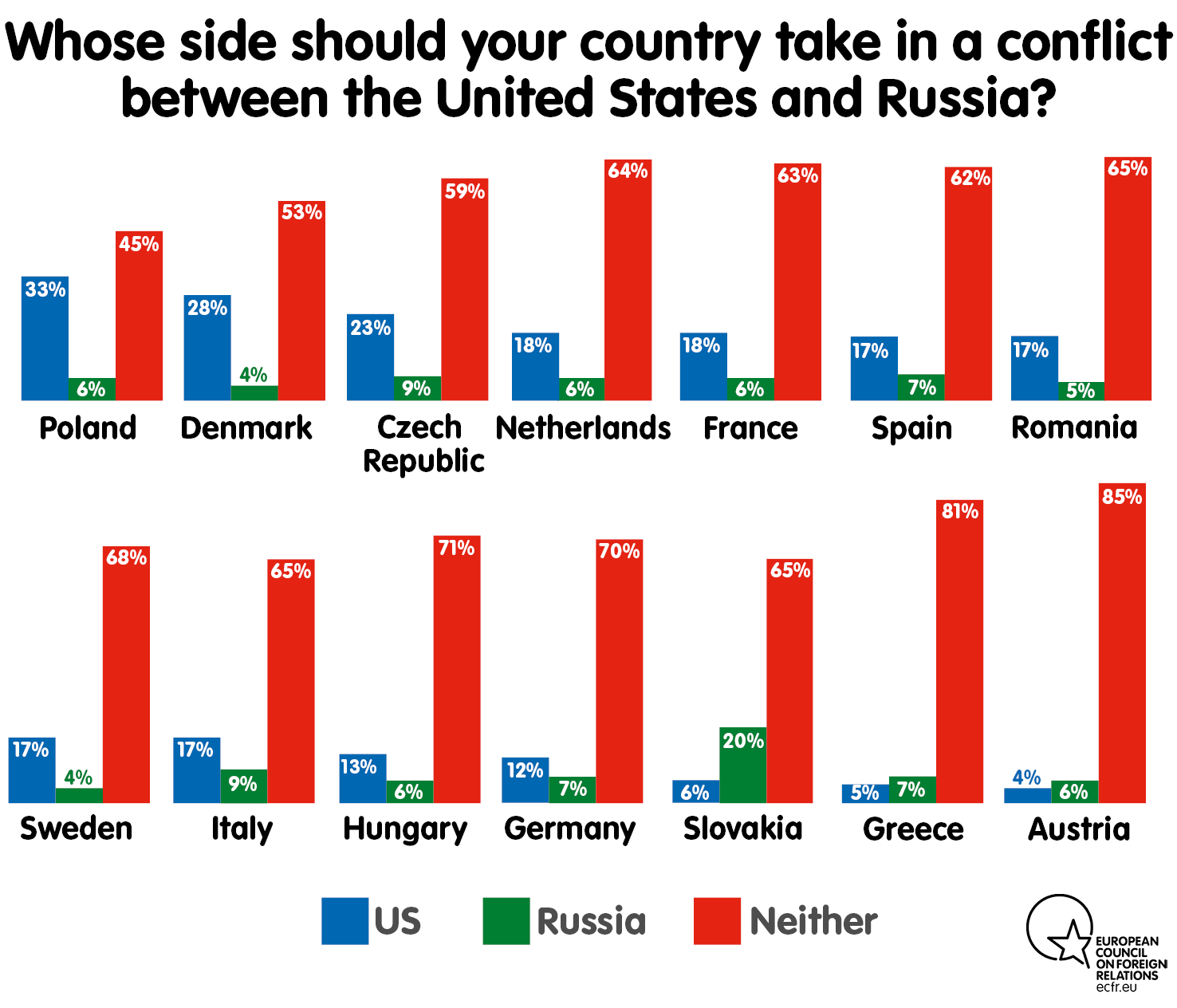

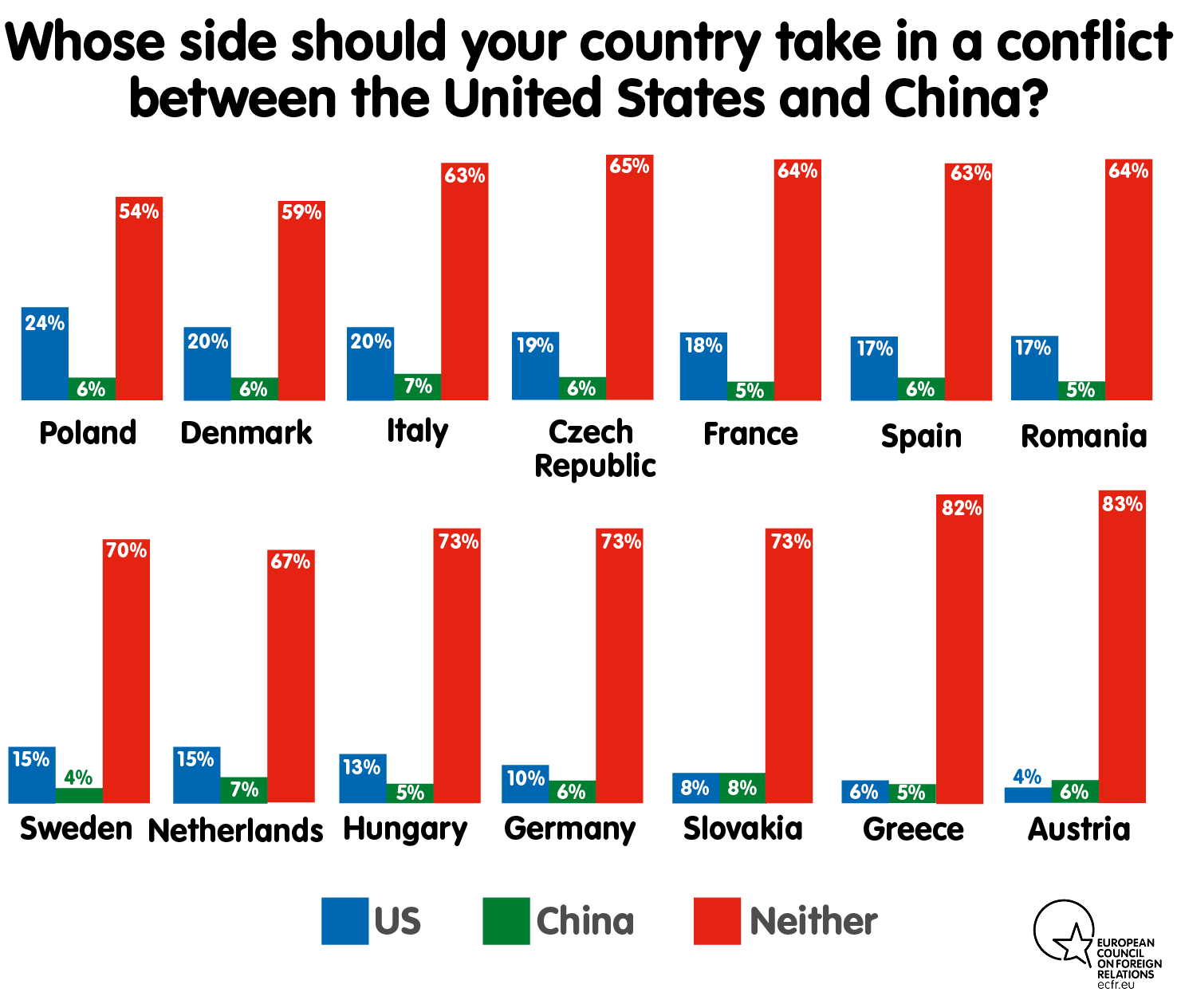

However, European voters appear to want the EU to become a strong, independent actor using a non-confrontational strategy. In conflicts between the US and either China or Russia, they have a clear preference for the EU to remain neutral, pursuing a middle way between competing great powers. In all but one member state, most people favour such neutrality in both scenarios. The exception is Poland, where most citizens would want the EU to side with the US in a dispute with Russia. And, even there, 45 percent of people would opt for neutrality.

This suggests that voters want the EU to be strong enough to avoid becoming a mere follower of other powers. In other words, their preference for EU neutrality in geopolitical disputes implies that they would favour the concept of European strategic sovereignty that ECFR’s Mark Leonard and Jeremy Shapiro set out in their recent paper “Strategic sovereignty: How the EU can regain the capacity to act”.

Yet, as Leonard and Shapiro argue, one of the key challenges in developing the EU’s role as a foreign policy actor is in overcoming national governments’ tendency to jealously guard their authority in the area.

ECFR’s survey data suggest that this phenomenon stems from national governments’ double misreading of the European electorate. Voters will not only tolerate EU leadership in relations with other major powers (since, as outlined above, voters view the ability to work as a bloc against superpowers such as the US, China, and Russia as one of the greatest potential losses if the EU collapsed) but are relatively comfortable with the idea of the EU protecting their economic interests – as long as it can demonstrate that it is capable of doing so.

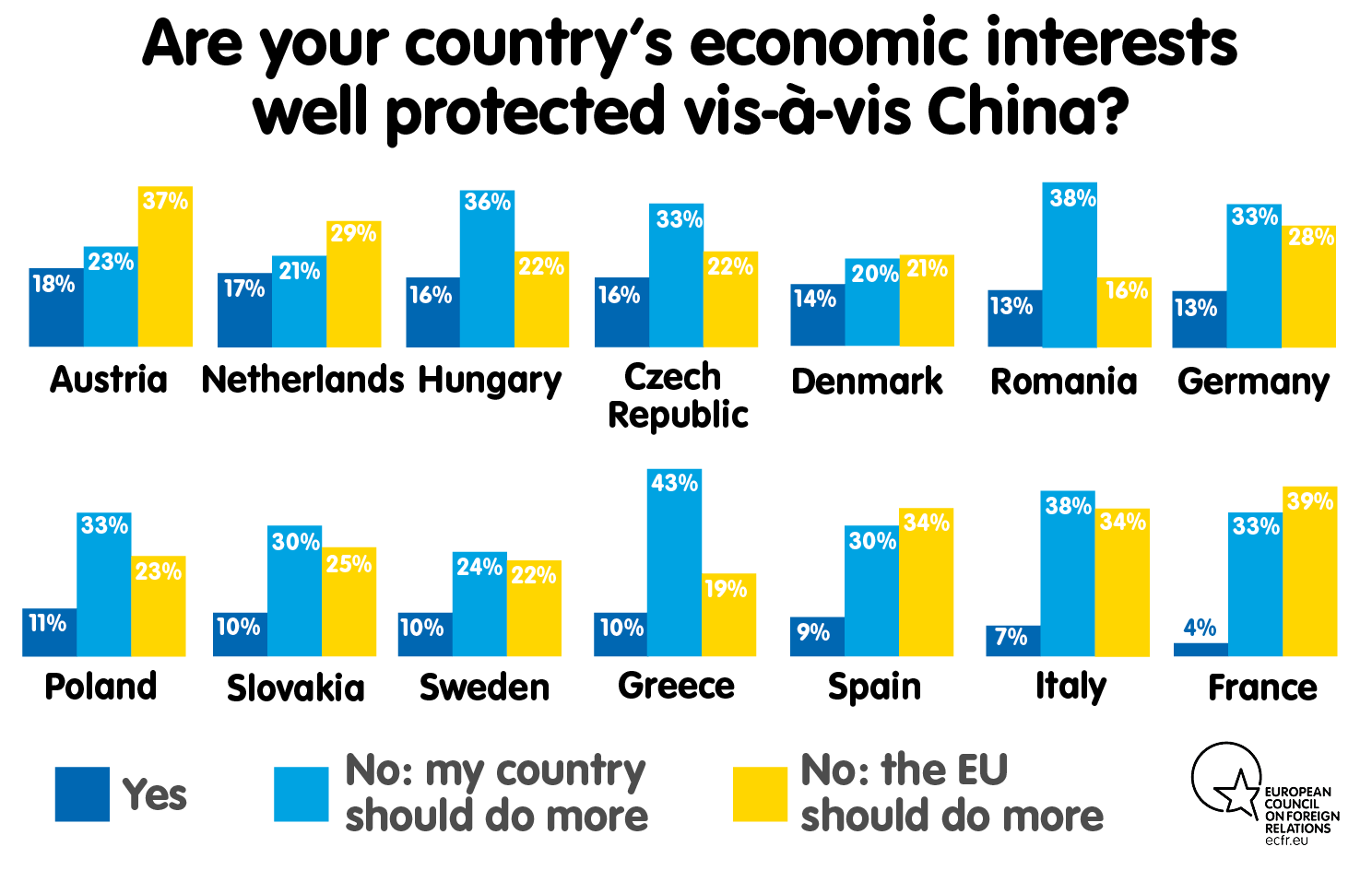

The EU’s institutions have begun to refer to China as not only an economic competitor but also a systemic rival. European voters also appear to be wary of the country, with no more than 10 percent of them in any member state suggesting that the EU should side with Beijing over Washington in the current Sino-American trade war. But, worryingly, voters are highly sceptical of the EU’s ability to protect their economic interests in trade wars: less than 20 percent of voters in each member state feel that their country’s interests are well protected from aggressive Chinese competitive practices. Nonetheless, they have mixed views on whether the EU or their national government should address this problem. In every member state except Austria, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and Spain, voters generally see national governments as better suited than other authorities to protecting their interests from China.

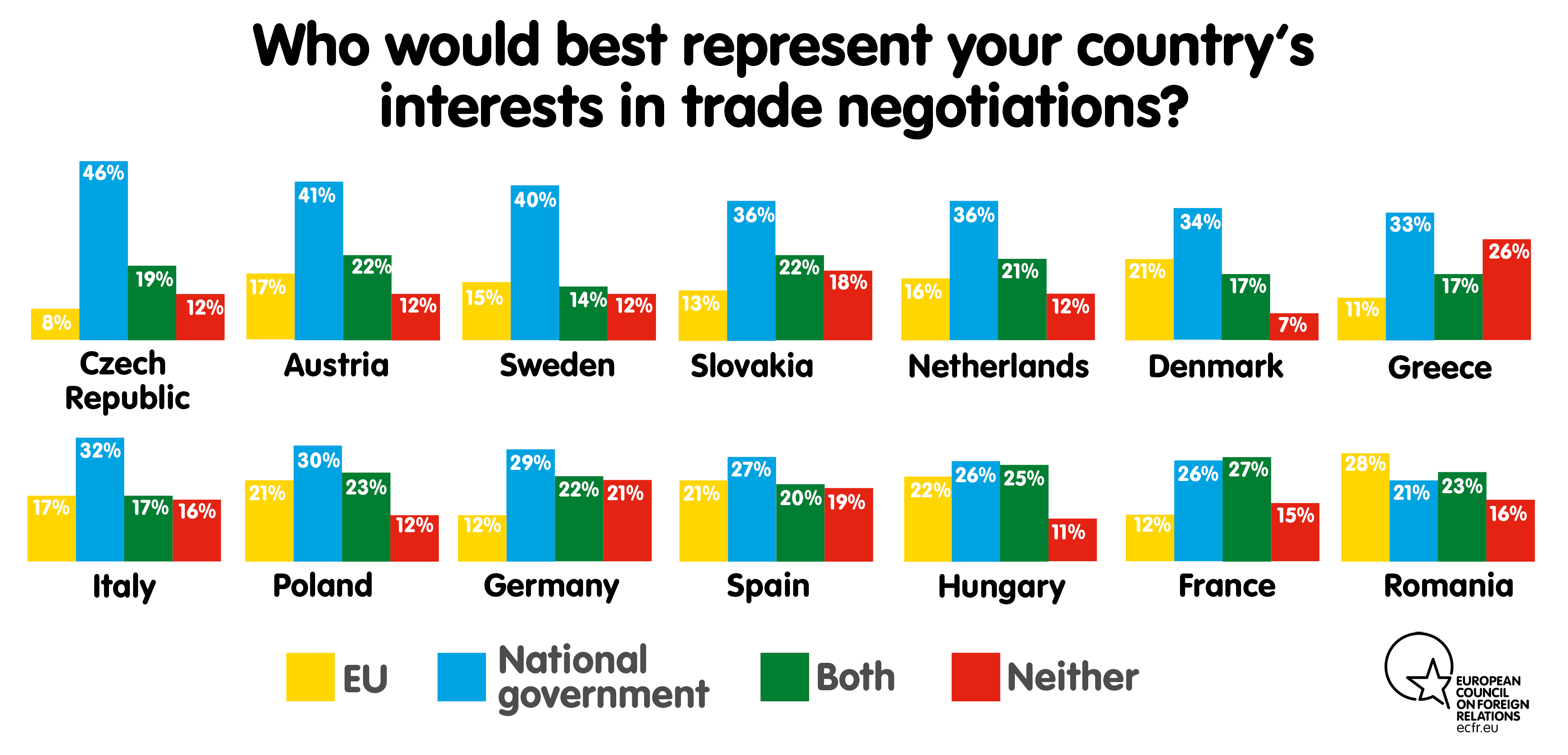

Similarly, voters in every member state aside from France and Romania saw their national government as better suited than other authorities to representing their country’s interests in trade negotiations. Indeed, in ECFR’s survey, this viewpoint was especially prevalent in Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, the Netherlands, Slovakia, and Sweden.

Given that trade policy is one of the EU’s responsibilities under its treaties, a key challenge for the new leadership of the bloc’s institutions will be answering voters’ calls for European strategic sovereignty without simply demanding further centralisation of decision-making on foreign policy in Brussels. Leonard’s and Carl Bildt’s recent paper “From Plaything to player: how Europe can stand up for itself in the next five years” sets out a vision for how this could be achieved under existing treaty arrangements. They advocate for the high representative to set the EU’s foreign policy agenda in line with an overarching strategy; a renewal of the relationship between member states and the EU institutions responsible for foreign affairs; and for greater use of core groups of member states to pursue foreign policy goals in certain areas. To make this shift, European leaders will need to develop and communicate a clear narrative on why closer cooperation on foreign policy will create the kind of EU voters want – one that is strong enough to take its own decisions and follow its own path.

The EU will also need to demonstrate that it can produce results on the global stage – an effort that national governments can assist by, where appropriate, sharing credit for successes with the bloc and acknowledging that they would have failed to achieve voters’ goals without greater cooperation at the European level. The EU-national balancing act that European voters want their leaders to perform on foreign policy will have a significant effect on the major challenges Europe faces. A successful performance of this balancing act could create the basis for greater pooling of diplomatic and military resources in the long term. By achieving results on key foreign policy issues, European leaders can enhance the EU’s credibility as a global actor among both its geopolitical competitors and voters at home – which may, in turn, justify closer coordination on foreign policy between member states.

A sense of control

During the 2015-2016 political crisis around migration, the leaders of many EU member states and institutions lost voters’ confidence over their handling of the surge in migrant arrivals. This was only partly due to EU citizens’ panic about how governments could manage the sharp rise in arrivals as austerity rocked Europe, causing public services and welfare systems to crack under intense pressure. For the most part, it resulted from their sense that EU institutions and governments had lost control of the situation. Some countries – particularly Sweden, and to some extent, Germany – believed that the EU was not helping them deal with high per capita levels of immigration. Others – not least Greece and Italy – believed that other member states expected them to play an outsized role in managing migration. In response to these perceptions, national governments increasingly pursued a unilateral approach to migration, gradually abandoning their attempts to forge an EU consensus on the way forward.

The key lesson from this period is that the appearance of control matters a great deal to European voters’ tolerance of policymaking at the EU level. They are far more likely to be willing to centralise decision-making powers if they can see that this will address the pressing challenges of the day. In contrast, they are relatively unlikely to accept centralisation as insurance against future problems – as can be seen in their attitudes towards various areas of foreign policy, shown in ECFR’s survey data.

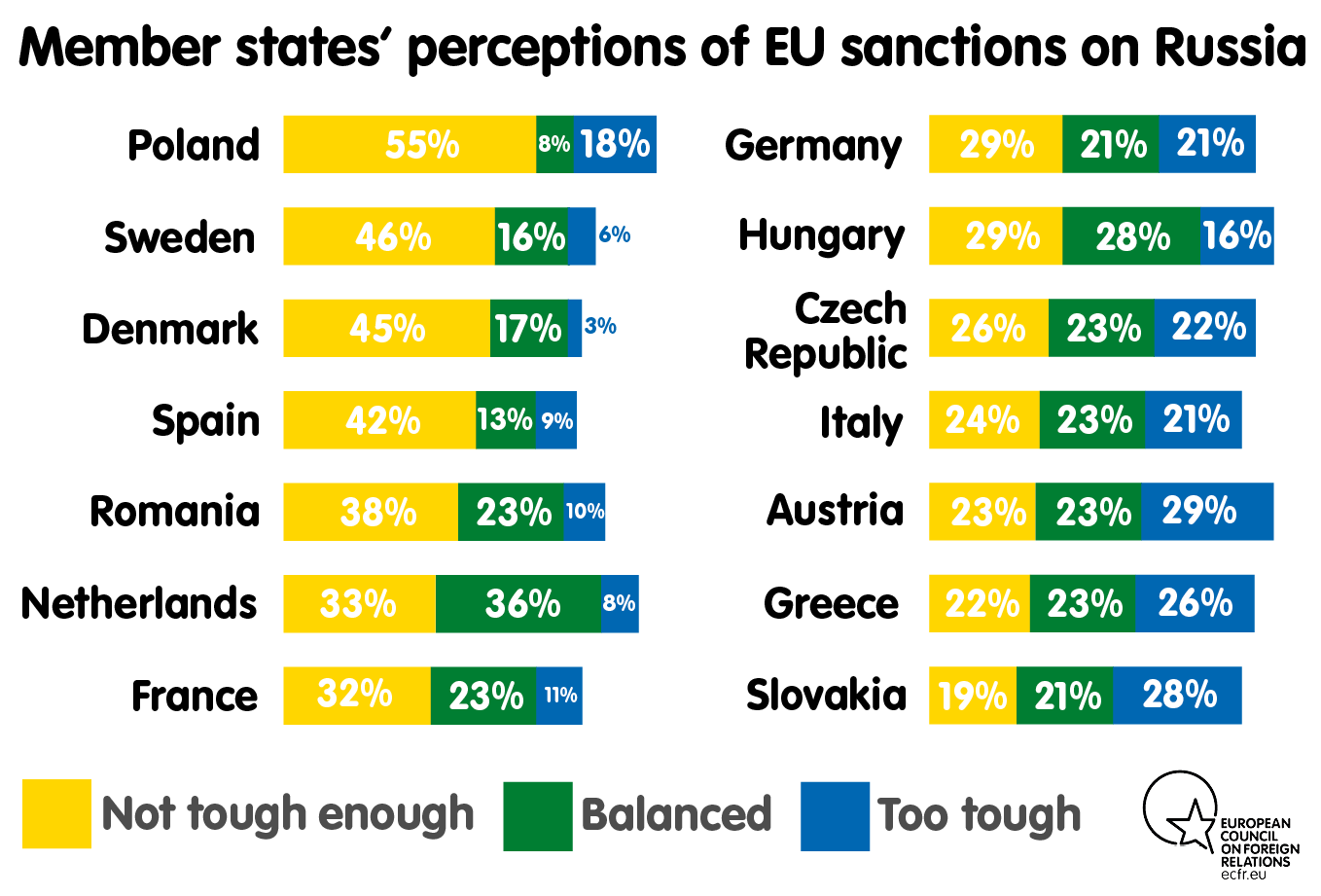

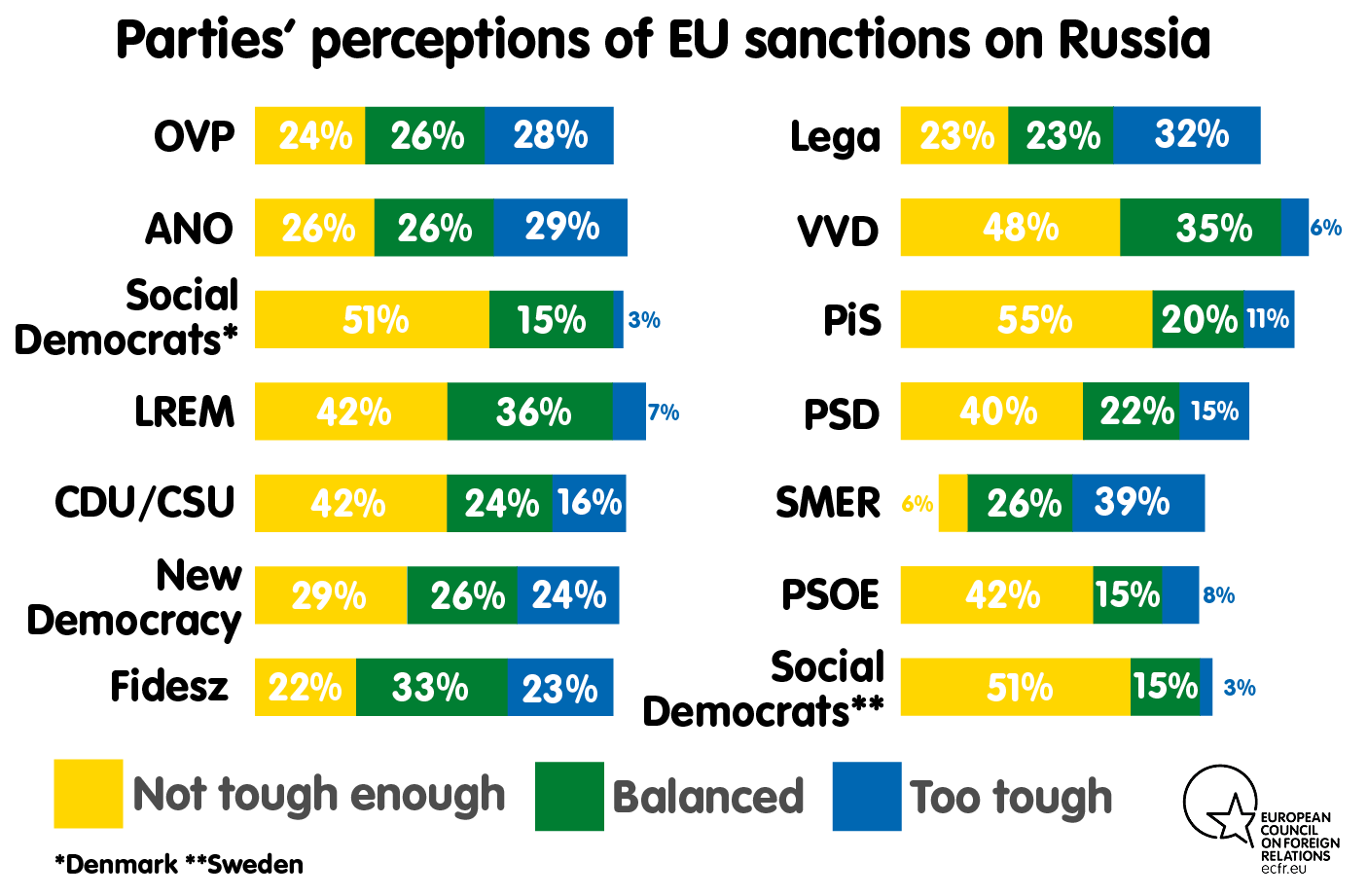

Russian aggression is one of the highest-profile foreign policy challenges Europe currently faces. This is perhaps truer in Helsinki or Warsaw than it is in Dublin or Madrid but, nonetheless, developments ranging from Russia’s war on Ukraine to its alleged interference in European elections are never far from the headlines in Europe. In this environment, the EU can only appear to be a mature and independent global actor if it has a clear policy on how to contain this threat and, crucially, convinces voters that everything is under control. Member state governments currently seem to be succeeding on this front: so far, they have been unified in maintaining the sanctions they imposed on Russia following its annexation of Crimea. This approach mirrors public support for a hard line on the country: ECFR’s survey found that, in most member states, more than 50 percent of voters viewed the EU’s policy on Russia as either balanced or not tough enough (the exceptions were Austria, Greece, and Slovakia).

This trend is even clearer among supporters of parties in government, with only those who voted for Slovakia’s SMER-SD suggesting that the sanctions are too tough. Coupled with a widespread sense of vulnerability to Russian interference in European political systems, this suggests there is little domestic pressure on the European Council to lift the sanctions.

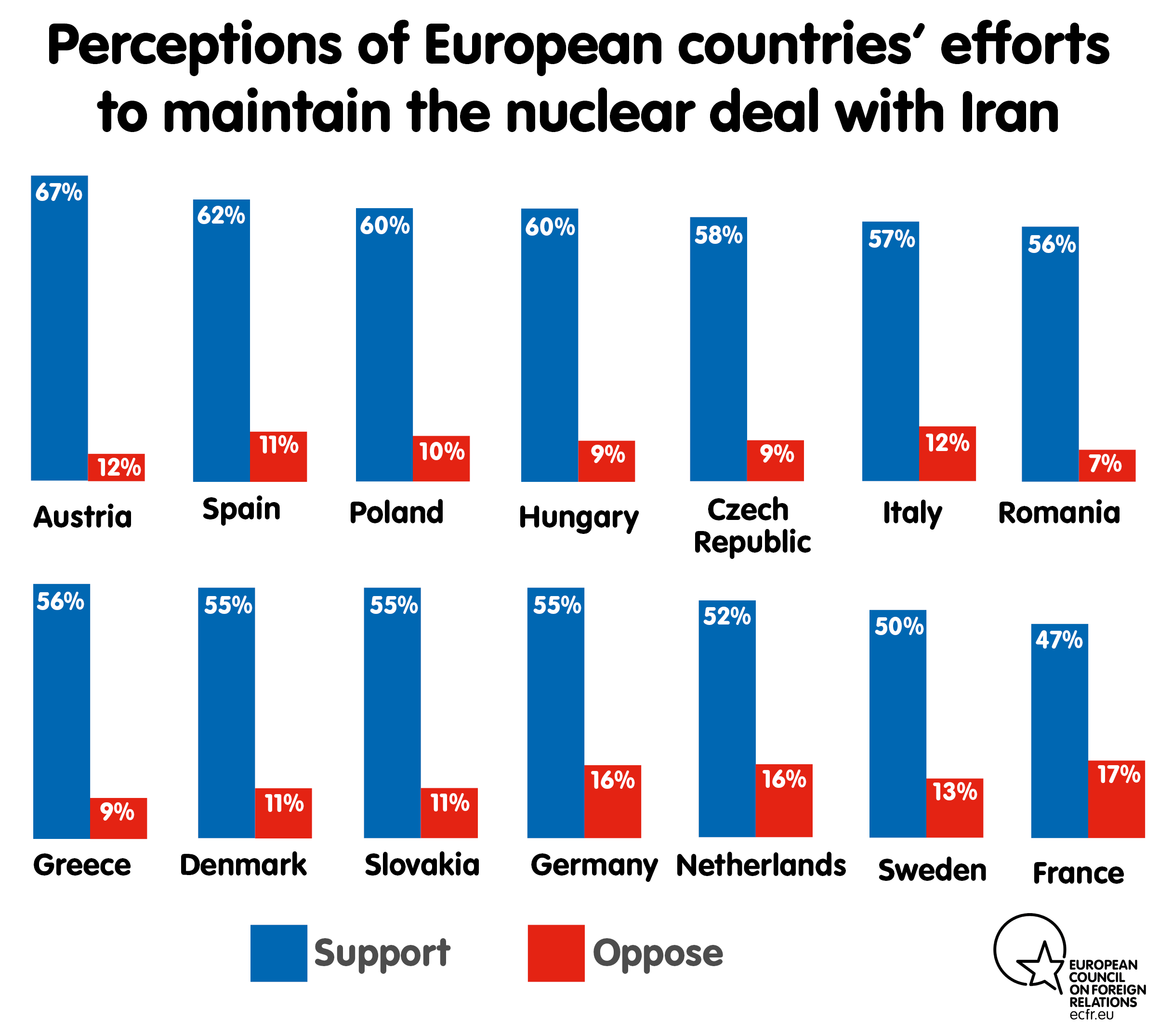

Strong support for EU efforts to exercise some control over difficult, unpredictable relationships is also evident in voters’ attitudes towards the Middle East and north Africa. For instance, ECFR’s survey shows that, despite significant divisions between European governments on many areas of policy on the region, there is a strong public support for the EU’s efforts to preserve the nuclear deal with Iran.

On both Russia and Iran, public support for the use of sanctions and brokered deals may be rooted in the idea of the EU as an actor that can control a situation. Unfortunately, the results of foreign policy are not always immediately obvious in the short or medium term.

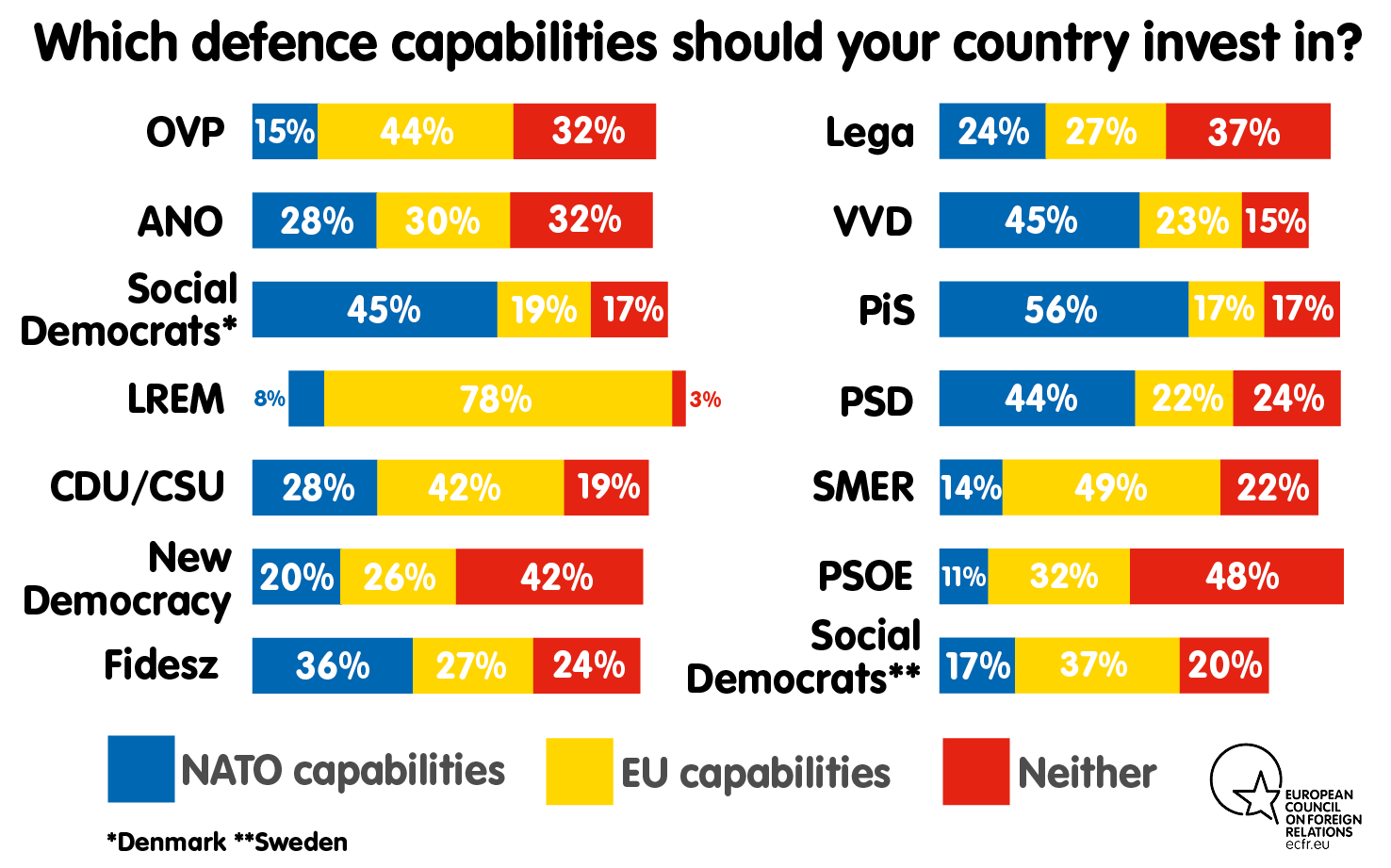

The EU will only be able to enhance its geopolitical power if it develops new ways to change the behaviour of third countries. Yet, as ECFR’s survey data demonstrate, it is unclear whether there is widespread support for doing so. For example, Ulrike Franke’s and Tara Varma’s recent paper “Independence play: Europe’s pursuit of strategic autonomy” shows that EU governments are divided on whether and how to pursue such autonomy in security and defence.

This divergence of views can also be seen among voters. ECFR’s survey data show that they are split over whether to invest only through the NATO framework or also by strengthening the EU’s capabilities. Among supporters of parties in government, La République En Marche! voters (in France) have the strongest preference for European investment while Law and Justice party voters (in Poland) have the strongest preference for the NATO framework. This underlines a striking shift in the way that Europeans think about their security – away from a default assumption that they can rely on US capabilities.

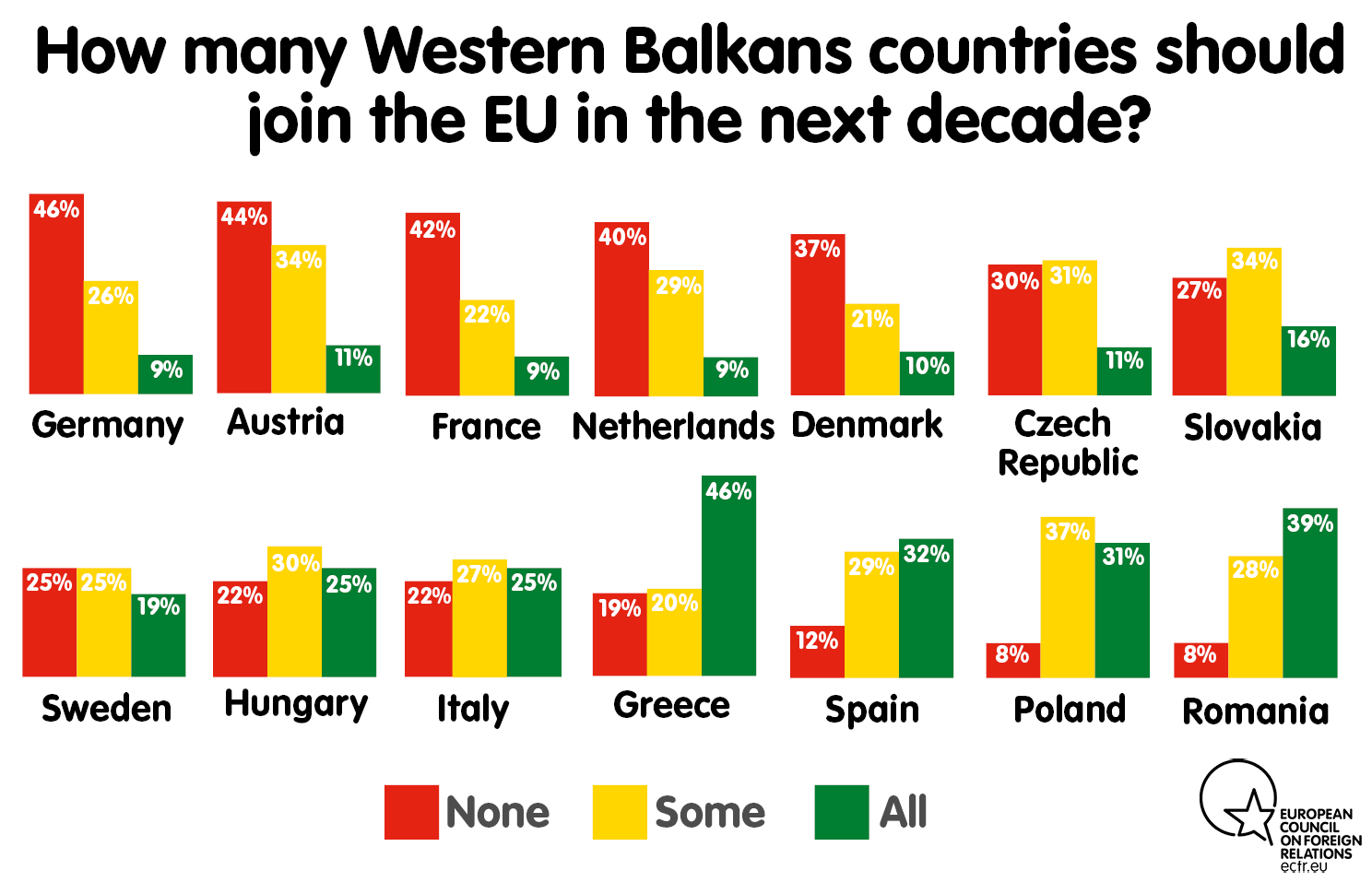

Voters’ attitudes towards EU enlargement also reflect their limited tolerance of major foreign policy initiatives that are only likely to pay dividends in the distant future. Until recently, EU policymakers portrayed enlargement as a vital tool for stabilising the EU’s eastern neighbourhood – with the newest member of the EU, Croatia, only joining in 2013. However, as ECFR’s survey shows, Europeans are lukewarm on further enlargement at best. Poland, Romania, and Spain are the only member states in which more than 30 percent of voters believe that more countries in the Western Balkans should join the union in the next 10-20 years. In many member states – particularly net contributors to the EU budget such as Austria, France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands – more than 40 percent of supporters of parties in government oppose enlargement.

Thus, the EU’s accession negotiations are made even more complex by significant domestic opposition to enlargement. European leaders will need a new policy on the Western Balkans that recognises that EU citizens do not see the region as important to their security. The argument that the EU should make good on its long-term promise to these candidate countries is unlikely to hold much weight with voters. Indeed, the idea of a Europe that is in control of its own destiny – free to make choices that are in its best interests – is central to their support of the bloc’s development as a geopolitical actor.

European leadership on climate change and migration

Climate change and migration are two of the key issues on which voters believe there is a clear need for action at the EU level. More than half of EU citizens in the countries ECFR surveyed – aside from the Netherlands – see climate change as a challenge that should take priority over most other topics. In the first half of 2019, there was an increase in the number of people who perceived climate change as important in four of the five biggest member states of a post-Brexit EU (Italy was the exception). And the new European Parliament has a strong mandate for action on climate change: 62 percent of MEPs are from parties that promised greater EU cooperation on the issue, and 56 percent are from parties committed to reducing carbon emissions. As a result, the European Parliament will try to hold other EU institutions to account on climate policy.

Meanwhile, European voters are increasingly convinced that migration policy should include development aid targeted at the problems that cause people in third countries to travel to Europe. A lack of economic prospects in source countries is one of the major drivers of migration to Europe. Although voters most often favour greater efforts to police the EU’s external borders, they see increased economic assistance to developing countries as the second-most important way to discourage migration. An average of 65 percent of people in member states – and no less than 50 percent in any given member state – support the latter approach. While most relevant research suggests that development aid at its current level will do little to reduce migration, this is unlikely to stop European governments from pursuing the approach given that there is strong support for it among voters.

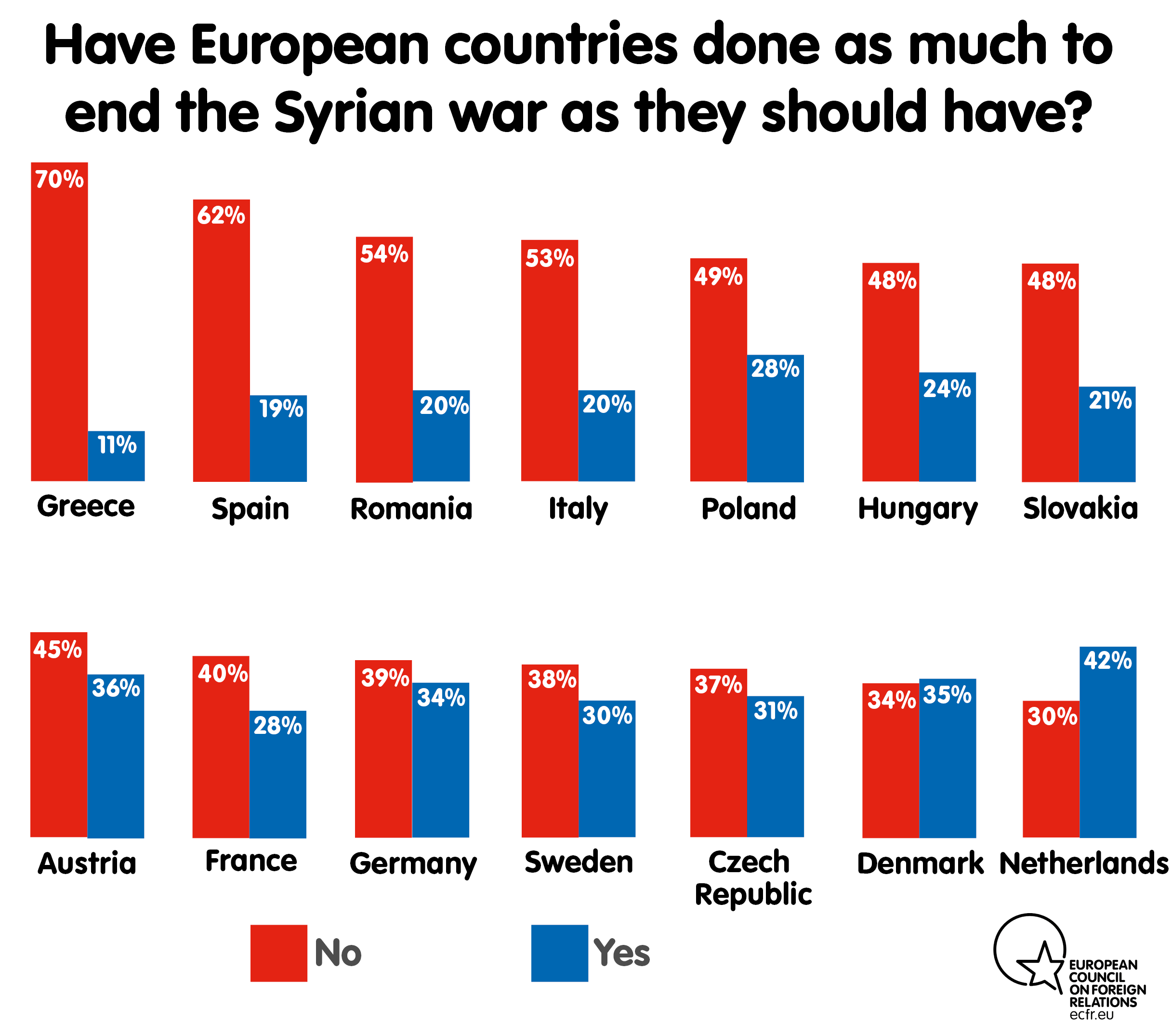

Conflict-related instability is another major driver of migration to Europe. ECFR’s surveys show that Europeans believe their diplomats should pay more attention to this driver as well. For instance, in 12 of the 14 countries ECFR surveyed, a majority of voters believed that the EU should have done more to address the Syria crisis.

If they ignore this call for action on these key issues at the European level, policymakers risk showing that they are out of step with public opinion on the role that foreign policy should play in tackling current challenges. To use the mandate voters have offered them – for empowering the EU as a cohesive geopolitical actor – member states and EU institutions must address the causes of voters’ sense of insecurity.

Where more Europe is part of the answer

Since the Lisbon Treaty entered into force in 2009, the EU has pursued initiatives in specific areas of foreign policy, such as security and defence cooperation, to gradually build up the bloc’s geopolitical capabilities. ECFR’s survey data suggest that, at a time of intensifying geopolitical competition, voters increasingly support the EU’s efforts to become a cohesive power. Europeans believe that, in this competitive world, their interests are largely aligned with one another. Counterintuitively – given its increasingly politically fragmented nature – foreign policy may be one area in which there is a growing sense among voters that action at the EU level is the answer.

But policymakers will have to earn the right to enhance the EU’s foreign policy power. To do so, the European foreign policy community will need to produce tangible results and acknowledge the messages voters have sent them. Given their fears about Europe’s place in the world, voters will not tolerate indifference to their concerns about foreign policy any more than they will in other areas.

Most EU citizens believe that they are living in in an EU in which they can no longer rely on the US security guarantee; they want the EU to halt the enlargement process and take greater collective action to tackle the challenges of a globalised world. Should the new leaders of the EU’s institutions fail to adjust to this reality – choosing to revert to unthinking transatlanticism or a reliance on spreading European values throughout their neighbourhood with the promise of EU membership – they could lose the foreign policy mandate that voters have offered them.

The more confidence Europeans have in the EU as a geopolitical actor, the more likely they are to accept the centralisation of powers. The political environment may currently make it difficult to institute qualified majority voting in many areas of foreign policy, but this could change if the EU demonstrates that it has a growing capacity as a foreign policy actor – and that it is not on the defensive – in the coming years.

The new leadership of the EU’s institutions now needs to take brave decisions and accept – as voters have – that the world has changed. Public opinion is no longer an impediment to the creation of a more coherent and effective European foreign policy (if it ever was). This is not the moment for Europe’s policymakers to fear the will of the people.

Acknowledgements

As with all the reports in the Unlock series that ECFR has published in 2019, the author is greatly indebted to colleagues across the ECFR network for all their input into the research and production of this report. In particular, Pawel Zerka, Philipp Dreyer, and Pablo Fons d’Ocon carried out brilliant analysis of the data sets on which this report draws heavily (in the lead-up to ECFR’s Annual Council Meeting in June 2019). Discussions with, and insights from, Susanne Baumann, Swantje Green, Mark Leonard, Jeremy Shapiro, and Vessela Tcherneva have also been very important in shaping the report. Chris Raggett’s editing has improved the text enormously. The author would also like to thank the team at YouGov for their patient collaboration with us in developing and analysing the data set. Despite all these many and varied forms of input, any errors in the report remain the author’s own.

The ‘Unlock’ project

The ‘Unlock Europe’s Majority’ project aims to push back against the rise of anti-Europeanism that threatens to weaken Europe and its influence in the world. Through polling and focus group data in 14 European Union member states with representative sample sizes, ECFR’s analysis aims to unlock the shifting coalitions in Europe that favour a more internationally engaged EU. This shows how different parties and movements can – rather than competing in the nationalist or populist debate – give the pro-European, internationally engaged majority in Europe a new voice. We use this research to engage with pro-European parties, civil society allies, and media outlets on how to frame nationally relevant issues in a way that will reach across constituencies – as well as reach the ears of voters who oppose an inward-looking, nationalist, and illiberal version of Europe.

About the author

Susi Dennison is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and director of ECFR’s European Power programme. In this role, she explores issues relating to strategy, cohesion, and politics to achieve a collective EU foreign and security policy. She led ECFR’s European Foreign Policy Scorecard project for five years; since the beginning of this year, she has overseen research for ECFR’s Unlock project.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.