From myth to reality: How to understand Turkey’s role in the Western Balkans

Summary

- European fears of Turkish expansionism in the Western Balkans have no basis in reality.

- Turkey spots opportunity in the region – yet it actually wants the Western Balkans inside the EU and NATO.

- The AKP’s approach once deserved a ‘neo-Ottoman’ tag, but Erdogan has since refocused on personalised diplomacy and pragmatic relations.

- Western Balkans governments remain reluctant to act on Turkey’s behalf by pursuing Gulenists, despite overall warm ties.

- Europeans should cease questioning Ankara’s motives and work on shared goals instead – hugging Turkey close and keeping it out of Russia’s embrace.

Introduction

In October 2017, the president of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, made an official visit to Serbia. It was not the first time a Turkish leader had gone to the country. But it was the first occasion on which Serbs had received a Turk with such warmth.

Erdogan toured Belgrade with Serbian leader Aleksandar Vucic, visiting one of the capital’s burgeoning Turkish-run establishments – a cafe chain called Simit Sarayı. In the historic Kalemagdan, crowds cheered and snapped photos as the Turkish president explored the old Ottoman fortress. At an official dinner, Erdogan and Vucic enjoyed the banquet with their wives, as the Serbian foreign minister, Ivica Dacic – a Serbian nationalist, no less – serenaded the Turkish leader with “Osman Aga”, a traditional Turkish folk tune that the minister sang in Turkish.

Yet Turkey and Serbia had been on opposing sides throughout the cold war and supported different sides in the Bosnian war. For the Turkish public, the term “Serbian butcher” was in daily use throughout the 1990s, in reference to atrocities committed by Serbian forces in Bosnia. Meanwhile, Serbs have built much of their modern national identity on the denunciation of centuries of Ottoman rule. To Serbian nationalists such as Vucic and Dacic, the 1389 battle of Kosovo, in which Ottoman forces defeated the Serbs, is the pivotal moment in Serbia’s national ethos. It is not just Serbian nationalism but also the symbol on the flag of modern Turkey, the crescent and star, that is said to have emerged from the blood-soaked battlefields of Kosovo – according to a legend cited in history textbooks in Turkish schools.

For Europeans looking on, the banquet and serenade were not even the greatest reason to worry. The next day Erdogan travelled with Vucic to Novi Pazar, the Bosniak cultural centre in Serbia. As he appeared on stage at a rally, the crowd, made up mostly of Bosniaks, chanted: “Sultan! Sultan!”

“Sultan”? What exactly was happening? Was Turkey making a comeback in the Balkans after a century-long hiatus? Was the Turkish empire returning, now under the leadership of Erdogan?

No. But Europeans examining this series of extraordinary events mistakenly interpreted Erdogan’s visit and Turkey’s accompanying overtures in the Western Balkans as signalling a renewed desire for regional hegemony – a worry that still lingers. “There is fear in Brussels that Turkey is trying to push into the Balkans”, recounts one senior EU official. “Turkey keeps telling us it has no bad intentions and supports [Western Balkans countries’] EU aspirations, but there is scepticism.”[1] Within European and Western Balkans policy circles and media outlets, speculation grew as to whether Turkey was seeking to present an “alternative” model for the Balkans – after Russia and the European Union. Speaking to the European Parliament, Emmanuel Macron declared that he did not want the Balkans “to turn towards Turkey or Russia.”

Ankara’s actual strategy in the Western Balkans, in fact, differs markedly from these knee-jerk assessments; more importantly, its capacity to implement any sort of expansionist strategy in the region is simply non-existent. Yes, Turkey has emerged as a player in the Balkans in the past decade, and its economic and political influence has grown since the end of the 1990s Balkans wars. True, Ankara does view the Balkans as part of its geographical and emotional hinterland: many citizens of Turkey have ancestors that came to Anatolia during the Balkans wars of the early twentieth century.

But Turkish and European leaders alike have greatly exaggerated the country’s power and intentions. Turkish leaders like the myth of Turkish power for internal propaganda reasons. Whatever dreams of Ottoman glory Turkish leaders may have in their private moments, these do not form the basis of Ankara’s Western Balkans policy. In reality, Turkey is neither an alternative or even the biggest economic actor in the region. It does not seek to peel the Western Balkans away from the EU. Nor does it see itself as a counterbalance to Russia. Turkey is indeed taking steps to strengthen its relationship with Western Balkans countries; it would like to be taken seriously in the region, and it retains its interest in the protection of Muslims there. But none of this is on a par with the EU’s economic and political influence in the region or a threat to it – at least for the moment.

This paper pulls back the many layers of myth and misperception that shroud the issue. It takes a sober look at what Turkey is doing, what its fundamental goals in the Western Balkans are, and how far the country still is from achieving them. It provides an Ankara-centric view of the region, with the aim of identifying areas of cooperation and potential points of divergence between Turkey and the EU. The paper identifies three distinct phases of Western Balkans policy under Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) government, charting its shift from: ongoing Atlanticism in the party’s early years of government; to an extended period under foreign minister and, eventually, prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu, who accentuated the Ottoman inheritance; to a pragmatic shift back under a newly empowered Erdogan, retaining some emphasis on the imperial past, but mostly focusing on trade.

Underpinning all these shifts are Turkey’s ongoing commitment to: transatlanticism; trade links; and Muslim communities in the region. And, as with much else in contemporary Turkey, Erdogan towers over all this: his pragmatic approach to the region and, more recently, his rivalry with influential religious leader Fethullah Gulen, have also left their imprint on Turkey’s Western Balkans policy.

This could change if, as this paper warns, Turkey exits the Western camp and seeks a closer alliance with Russia in the Middle East and the Balkans. For the moment, this remains unlikely. But Europeans should take care not to push Turkey into seeking out new alliances in the Western Balkans and elsewhere.

An emotional hinterland, a theatre of competition

The Balkans hold a particular emotional significance for Turks, regardless of who is governing Turkey at any given time. The Ottoman Empire was in large part a Balkans empire – not only in terms of territorial space but also in terms of its ruling cadres and bureaucracy, many of whose members came from families with roots in the Balkans. Waves of Muslim immigration to Anatolia started in the late nineteenth century and continued until the early decades of the Turkish republic. It is impossible to know the exact number of Turkish citizens who have a family background in the Balkans, given that estimates vary. Turkey’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, and many of the leading cadres in the late Ottoman and early republican periods, had Balkans forebears. Today, entire neighbourhoods of Istanbul, such as Bayrampasa, Pendik, and Arnavutkoy (Albanian village), have populations that claim to be descendants of Balkans emigrants – though they evince little interest in day-to-day politics in the Balkans so long after the migration took place. Meanwhile, Bosnia has held a special place in Turkish public opinion since the 1990s, when Turks demonstrated overwhelming public sympathy for the suffering of Bosnian Muslims during the war, at times even taking to the streets to show their concern. Warm feelings towards Albania and Kosovo stem, in part, from an awareness of the high number of Turkish citizens with Albanian roots.

The sense of closeness is abstract, but it remains right up to the present day in fields beyond politics and economics. For example, one of Turkey’s most popular public figures is Jelica Obradovic, the legendary Serbian coach who brought European championship success to the Fenerbahce basketball team – witness the transformation of popular Turkish secularist slogan from “We are soldiers of Mustafa Kemal” to “We are soldiers of Obradovic”. This has raised the profile of Serbian and other Balkans players on Turkish teams, such as Nikola Kalinic and Bogdan Bogdanovic, while popular Turkish basketball players such as Hidayet Türkoglu have roots in the Balkans.

Yet the Balkans does not feature among the top issues in Turkish public opinion. Turkish newspapers do not run stories about political developments in the region and pollsters do not find the Balkans significant enough to even inquire about Turkish perceptions of the region – unlike Israel, the EU, Middle East, and the United States. There appears to be overall support for good relations, as shown by one recent debate in the Turkish parliament on the Balkans, in which both the government and the opposition expressed their support for close ties.

Alongside economic and security relations, Turkey also harbours a desire to be the patron saint of the Muslim populations of the Western Balkans. In this respect, Erdogan finds in the region the prestige that he does not have elsewhere in Europe. But, with the exception of minority Muslim populations in Bosnia and a few other places, this influence is very limited. The Western Balkans is not the focal point of Turkish foreign policy or public debate in the way Syria and the EU are.

Indeed, in terms of its desired outcomes for the Western Balkans, the current Turkish government – like its predecessors – does not see the integration of the region into the European framework as something that runs counter to Turkish interests. In interviews in Ankara, senior Turkish officials emphasise that Turkey is supportive of EU enlargement in the Western Balkans, and they express frustration that Europeans fail to see this.[3] From Turkey’s point of view, the EU framework brings stability and prosperity to a troubled region with which Turkey has friendly relations and growing economic ties. The Balkans is Turkey’s gateway to Europe – literally, as it is the route that Turkish trucks use to export to the EU, the country’s main trading partner. Turkey has a further interest in the region in that, in terms of EU membership for Western Balkans countries, it sees friendly governments inside the EU as an indirect way into the heart of Europe. Especially at a time when Turkey’s relations with Europe are suffering, it makes sense for the country to want Western Balkans states in the European club.

Naturally, the Western Balkans is a region in which Russia takes a particularly strong and active interest. It is important to note that, despite Turkey’s growing ties with Russia, there is no Turkish-Russian coordination in the Western Balkans. Historically, the two countries have competed for power in the Balkans and, in recent times, supported different visions. Ankara does not look upon Russian expansion on the periphery of Europe in favourable terms. Turkey’s interest in the region has not been aligned with Russia’s cultural and political project for the Balkans. Erdogan and Russian leader Vladimir Putin have a personalised and pragmatic relationship that has resulted in a boost in bilateral trade and greater Turkish-Russian coordination in Syria in the past few years. However, this is still not a state-to-state institutional relationship. It also does not promise to spread Russian influence in places other than Syria. While obsessing about Turkey’s influence in the region, Europeans should recognise that there is no Turkish-Russian axis in the Western Balkans, and try to preserve this state of affairs by not pushing Turkey outside the transatlantic and European framework – including into a place that is close to Russian positions on regional matters.

In short, Turkey’s relationship with the Western Balkans in involved and many-layered – but its aim is not to present an alternative model for the region. The country does not view the EU as a competitor for influence there and, in fact, welcomes increased EU integration. The Western Balkans has a special hold on Turkish hearts, and Turkey expects to be taken seriously in its own hinterland. But there is no evidence that this extends to a wish to dominate the region. It is instructive, however, to examine more closely the evolution of Turkey’s approach to the Western Balkans since the turn of the century, as the relationship is dynamic, nuanced, and contested.

The AKP and the Western Balkans: Three phases

Since taking power in 2002, Turkey’s conservative AKP has adopted three broad, successive approaches towards the Western Balkans: a continuation of its traditional Atlanticism; a ‘neo-Ottoman’ turn; and a pragmatic reset under Erdogan.

The AKP’s early years: Atlanticism continued

Before the AKP’s ascent to power in 2002, Turkey’s Western Balkans policy was in sync with that of its Western allies, particularly the US. This did not radically change after 2002. In the 1990s, Ankara’s partnership with Washington strengthened during and after the Yugoslavian wars. Turkey actively supported Muslims during the war in Bosnia and, in the aftermath of the conflict, it was eager to play an active role in stabilising the region. During that war and the Kosovo intervention, Ankara coordinated its policies closely with the Americans. It played an auxiliary role in regional security and stability issues during the conflicts, and later developed warm relations with the new governments in Macedonia, Bosnia, and Albania. At various stages both before and after 2002, Turkey also promoted these countries’ involvement with NATO, including by supporting Macedonia’s bid for NATO membership. Turkey was also active in post-conflict initiatives through the United Nations and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, contributing to peacekeeping operations in the region. After the war in Yugoslavia, the Turkish military developed close ties with Macedonia and helped train new military cadres there. Turkey was also the second country to recognise Kosovo’s independence in 2008 (after the US).

During this period, Turkey still saw itself strictly as a member of the Western alliance. As one of Turkey’s leading experts on the Balkans, Birgül Demirtas, notes: “Turkey’s traditional Western identity, and its interest in the maintenance of this identity in the post-Cold War period, was an important factor in the formulation of Turkish policies. By being active on the Balkan stage and undertaking supportive role for the Bosniaks in international platforms, Turkey attempted to prove its importance to the Western world.”[4]

Upon taking power, the AKP harboured a clear desire to reduce the influence of the Kemalist establishment in Turkey. It quickly won international credibility by pushing ahead with reforms to accelerate Turkey’s EU accession process. The Western Balkans were not a major feature of this period. To the extent that the AKP was interested in the region during its early years in power, this was in a continuation of previous governments’ policy of anchoring the Western Balkans in the transatlantic community and its institutions. The AKP’s foreign policy approach in general at this time was to maintain and improve its relations with nearby countries, dubbed “Zero problems with neighbours”. Turkey expanded visa-free travel and free trade zones with its neighbours during this period, which lasted roughly till the appointment of Davutoglu as foreign minister in 2009.

The Davutoglu era: A neo-Ottoman renaissance?

The second phase of the AKP’s Western Balkans policy came with the growing influence of Davutoglu from 2009 onwards. This phase was marked by an intensification of Turkey’s diplomatic outreach to the Western Balkans, which was peppered with references to the Ottoman past.

Davutoglu was no stranger to the Balkans. The Bosnian war had created a sense of outrage among Turkey’s Islamists in the 1990s. As an academic with close ties to the pro-Islamist Refah Partisi (Welfare Party), Davutoglu developed many of his ideas about Turkey’s global position in response to what was happening in the Balkans. As articulated in his seminal work, Strategic Derinlik (Strategic Depth), Davutoglu believed that, for Turkey to fulfil its historic destiny and emerge as a global power, it would need to complement its Western orientation with a stronger interest in the Middle East and the Balkans. During his tenure as foreign minister, the country became much more active in these regions. The founders of modern Turkey had seen the defeat and collapse of the Ottoman Empire during the first world war and rejected the Ottoman legacy both in geographic and imperial terms. Davutoglu thought differently: like most Islamists in AKP circles, Davutoglu believed that the Kemalist republic was reductionist, that the Ottoman legacy was not bitter but glorious, and that Turkey would only be able to fulfil its destiny if it exerted its soft power in former Ottoman territories.

In Strategic Depth, Davutoglu argued that Ankara should base its Balkans policy on Bosniaks and Albanians – the two significant Muslim populations in the region. He saw closer relations with these communities as the key to expanding Turkey’s influence in the region. But, as political scientist Birgül Demirtas notes, once he became a foreign minister, Davutoglu focused not only on Bosnia and Albania but developed close ties with Macedonia and Serbia as well.

In fact, as soon as Davutoglu became foreign minister, Turkey embarked on a dizzying diplomatic outreach campaign throughout the Western Balkans. Conflict resolution in Bosnia was first on the agenda. In 2009 Ankara launched its initiative to bring Bosnian Serbs, Croats, and Muslims together to address outstanding issues within Bosnia – partly as a consequence of the failure of the EU-led Butmir Process. An ardent proponent of boosting Turkey’s role in international arbitration, Davutoglu then established a second trilateral mechanism comprising Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia in 2010. Both mechanisms resulted in dozens of bilateral visits and summits, highlighting Turkey’s growing influence in the region. Political scientist Alida Vracic writes: “results were evident. The foreign ministers of Turkey, BiH [Bosnia and Herzegovina], and Serbia have come together nine times; the foreign ministers of Turkey, BiH, and Croatia have gathered four times since 2009. The highlight of these meetings was a first-ever meeting between Serbian President Boris Tadić and BiH President Haris Silajdžić. Consequently, Bosnia and Herzegovina sent an ambassador to Belgrade following a three-year absence. In 2010 the Serbian parliament adopted a declaration condemning the crimes in Srebrenica.”

A significant outcome of this was the positive impact on Turkey’s relations with Serbia. In April 2010, the leaders of Serbia, Bosnia, and Turkey signed the Istanbul Declaration, with the Serbian and Bosnian presidents coming together for what was hailed as a “historic” summit. Much of this was a result of months of shuttle diplomacy by Davutoglu. Abdullah Gül, Turkey’s president at the time, posed in a photo holding both presidents’ hands and said: “Those who read history should know that the Balkans would have peace and security under a united roof. Now that roof is the large European Union umbrella.”

Davutoglu’s focus on Serbia resulted in a historic thaw in relations between Serbia and Turkey, countries that considered themselves to be traditional opponents. Turkey considered it essential for its outreach in the Balkans to draw Serbia into the European framework, to help smooth out differences between Bosnia and Croatia. This was complementary to EU efforts at that time.

As a journalist travelling with Davutoglu during this period, the author had the chance to witness some of this hyperactive Turkish diplomacy, shuttling from Bosnia to Croatia to promote dialogue immediately followed by similar engagements in the Middle East such as mediation efforts in Yemen and Lebanon. While criticised by the secular establishment for deviating from Turkey’s traditional focus on the Western alliance, Davutoglu’s diplomacy was not without results. The Istanbul Declaration marked Belgrade’s recognition of Bosnia’s territorial integrity and the return of ambassadors between the two countries. Turkey also pushed for Bosnia’s membership of NATO’s Membership Action Plan. Its influence in the region was undoubtedly growing.

Meanwhile, Turkey continued its policy of free trade agreements and visa-free travel with countries in its neighbourhood, including those in the Balkans and the Middle East. By 2018, Turkey had finalised free trade agreements with all Western Balkans states.

Davutoglu was a keen believer in Turkey’s soft power potential. In terms of cultural influence, the AKP government during this period put great emphasis on the expansion of the activities of the Turkish aid agency (TIKA) and the establishment of Yunus Emre cultural centres across the region. Fashioned after the Goethe Institute and the British Council, these local cultural institutions were supported by the Turkish government with the intention of spreading Turkish language and culture. From 2007 onwards, Turkey opened two Yunus Emre centres in Albania, three in Bosnia, one in Serbia, three in Kosovo, and three in Macedonia. This was in parallel with the rising popularity in the region of Turkish television such as Magnificent Century, which depicted the life and court of Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. The Turkish government saw Turkish language classes in Sarajevo and other predominantly Muslim areas of the Western Balkans as an instrument for spreading its cultural influence. By 2012, Turkey had also expanded its scholarship programme to Balkans students who wanted to go to university in Turkey.

The results of the Davutoglu-era campaign to spread Turkey’s soft power in the Balkans were mixed. On the one hand, its high-intensity diplomacy and cultural initiatives raised Turkey’s profile and generated positive sentiments among the elite – in line with the country’s growing self-confidence in the international arena. On the other hand, the Balkans has not exactly turned into Turkey’s “backyard”, despite Davutoglu’s dreams. Turkey was influential in politics, but limited in its cultural influence outside of the Muslim communities. Yunus Emre centres have not lived up to their potential to spread Turkish culture across the region, while Turkish has not become a lingua franca in the region as architects of the policy of soft power expansion planned.

One major drawback that Davutoglu and the AKP ignored in their analysis was bitter feeling about Turkey’s colonial past in the region. With the exception of Bosnia, most Balkans countries view the centuries of Ottoman reign in fairly negative terms. In trying to sell a more activist foreign policy at home – deviating from Turkey’s traditional transatlantic orientation – the AKP relied on Ottoman imagery and nostalgia for the empire.

Indeed, Turkish leaders seemed remarkably unaware of the gap between the propaganda power of their neo-Ottoman rhetoric at home and its reception abroad. In a speech in Sarajevo in 2009, Davutoglu claimed that: “Our history is the same, our fate is the same, and our future is the same. As the Ottoman Balkans has risen to the centre of world politics in the sixteenth century, we will make the Balkans, Caucasus and Middle East, together with Turkey, the centre of world politics. This is the aim of Turkish foreign policy and we will achieve this. To provide regional and global peace, we will reintegrate with the Balkans region, the Middle East, and Caucasus, not only for ourselves but for the whole of humanity.”

Davutoglu peopled his speech with historical figures from the Ottoman court, such as powerful sixteenth-century Ottoman grand vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, who had roots in the Balkans. He seemed unaware that the policy of taking small Christian boys from Serbian villages to raise them as courtiers and statesmen did not go down well in the region, even after 400 years. “This was the Ottoman Balkans”, he said. “We will re-establish this Balkans. People are calling me neo-Ottoman, therefore I don’t want to refer to the Ottoman state as a foreign policy issue. What I am underlining is the Ottoman legacy. The Ottoman centuries of the Balkans were success stories. Now we have to reinvent this.”

Erdogan himself repeated the salute to the Balkans at key events and other post-election victory speeches over the years, presenting Turkey as the saviour of Muslims in neighbouring countries. After local elections in March 2014, the Turkish leader made a live call to the Turkish-speaking village of Mamuşa in Kosovo. Its mayor celebrated Erdogan’s victory by saying: “The people of Kosovo, the Balkans, and Mamuşa are proud of you.” This episode was not intended for a Western Balkans or Kosovo audience. In fact, the call was part of a series of gestures to support the image at home of Erdogan as a “dünya lideri” (global leader) – or even “asrın lideri” (leader of the century), as AKP electoral propaganda and media outlets often suggested. It helped place Erdogan in a global league above his political competitors at home.

All that this amounted to, however, was an exaggerated view of Turkey’s influence in its neighbourhood, one which ignored the fact that many of the Balkans nation-states emerged out of nationalist struggles against the Ottomans. By resurrecting Ottoman imagery, AKP leaders assumed they were reminding the world of a golden past of peace and stability in the Balkans; they did not understand the deep-rooted sensitivities and historical bitterness that many in the Western Balkans still feel. The idea of a resurgent Turkish empire was only an easy sell at home. Muslim populations that might welcome a return of the glory days of the empire were in a tiny minority in most Balkans countries.

Somehow, Ankara’s relations with the Western Balkans survived the florid language of the Davutoglu period, tempering its grand ambitions in favour of a more realistic outlook. After all, Ankara remained supportive of the integration of Western Balkans countries into EU institutions and NATO – and, as such, remained an important ally for them. Despite historical sensitivities around the Ottoman era, Western Balkans countries came to value relations with a strong regional neighbour, and, when they needed to, ignored the Ottoman nostalgia emanating from Ankara. Vracic remarks that, in most countries, this represents a top-down desire for Turkish support, not a bottom-up yearning to give Turkey a hegemonic role in the region: “A clear separation of sentiments towards Turkey is much more visible in the Western Balkans. Whereas the political elites in the Western Balkans unanimously display almost divine devotion to the Turkish political establishment and nurture good relations, citizens with more liberal views dread the possibility of Turkey becoming more influential in the region, especially in light of the more assertive autocratic nature of President Erdogan’s regime.”

The one exception to this is Bosnia, where Turkey has remained popular for Muslims and life under Turkish rule is generally seen in positive terms. Erdogan has told a story, now something of an urban legend, in which Bosnia and Herzegovina president Alija Izetbegovic lies on his death bed while telling Erdogan that Bosnia is an “emanet” (precious keepsake) for Turkey. There is no indication elsewhere in the Balkans that populations have positive attitudes towards greater Turkish activism in the region.

Erdoganism: The victory of pragmatism

The third and most recent phase of the AKP’s strategy on the Western Balkans is a more Erdogan-centred and pragmatic approach. Since Davutoglu’s departure from public office in 2016, Turkey has reduced the pace and intensity of its regional activism and diplomatic initiatives. It has replaced this with a focus on greater economic ties and a prominent role for the Turkish president. This new period is marked by Erdogan’s direct engagement, through personal ties, with Western Balkans leaders. It is a pragmatic Erdoganism writ large.

On 9 July 2018, Erdogan held a swearing-in ceremony in his newly built palace compound in Ankara. Most European leaders snubbed the event because Turkey’s new constitution, approved through a referendum by only a tiny margin, granted sweeping powers to the president despite the Venice Commission’s warnings about the erosion of checks and balances. Nonetheless, Western Balkans leaders were in full attendance, side by side with African heads of state and close Erdogan allies such as the emir of Qatar and Venezuela’s leader. Heads of state and government from Bulgaria, Macedonia, Bosnia, Albania, Kosovo, and Serbia took front row seats at a grand celebration that marked the consolidation of absolute power in the hands of the Turkish president.

The leaders were to be reunited under Turkish auspices more than once that year: the opening of Istanbul airport in October 2018 saw a personal invitation extended to the leaders of Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, and Serbia. Whereas EU governments refused the invitations, Western Balkans leaders willingly obliged, likely due to Turkey’s significant role in their trade and external relations. The following month, Erdogan telephoned Vucic and Kosovan leader Hashim Thaçi to try to solve a border and customs dispute between Serbia and Kosovo.[5]

There is no doubt that Erdogan’s personal relations with Vucic, Thaçi, Bosnian leader Bakir Izetbegovic, and Albanian prime minister Edi Rama form the backbone of the newest phase of Turkey’s outreach in the Western Balkans. These personal interactions constitute Turkey’s top diplomatic channel in their countries. But this policy is also intended to reflect Erdogan’s supremacy as the strongest leader in the region. In his post-referendum (April 2017) phase, the Turkish leader has sought to cultivate an image of both regional strongman and paternal figure – not just to 84 million Turks, but to Muslims and regional leaders in the former Ottoman lands. In conversations in Ankara, bureaucrats like to throw in the phrase “elder brother” in describing Turkey’s role in its near abroad.[6]

Balkans leaders are aware of Erdogan’s soft spot for this image and do not seem to mind indulging it. They know that Erdogan wants the respect that he feels he does not receive from EU leaders, so they turn up at his invitation. This “diplomacy of turning up” is mutually beneficial. Each time Western Balkans leaders or even their families come to Turkey, they are given VIP treatment and high-level access.

This special friendship also allows Balkans leaders to show other great powers, such as Europe, that the Western Balkans is not without alternatives when it comes to alliances, furthering underlining Erdogan’s position as a regional leader. But there is a specific protocol in this relationship. Demirtas notes that Turkey likes to present itself as primus inter pares when it is among Balkans nations. The Balkans allows Turkey to feel like a regional superpower. According to its self-image, Turkey is partly responsible for and helpful to the development of Western Balkans countries, enhancing its political support for aid programmes through TIKA. “Turkey wants to be taken seriously in the Balkans”, one Turkish diplomat states. “It wants to be the primary actor in its own region, but not a hegemon to run it.”[7] In this arrangement, both sides benefit.

There are limits to Turkey’s involvement, though. The country does not become involved in domestic politics in the Western Balkans. Turkey tends to support whoever ends up in power, including, for example, a Serbian nationalist such as Vucic. It does not take sides in elections and, with the exception of Albania and Bosnia, the Muslim minorities that Turkey has an interest in are too small to fundamentally reshape politics.

Turkey still uses soft power instruments in the region to make its case. These include scholarships, language courses, and renovation projects. But Turkish language classes remain poorly attended, while much of TIKA’s developmental aid goes into the renovation of Ottoman-era buildings and mosques. To the Turkish government, the impact of TIKA aid in the Western Balkans is less important than its meaning back home. Eighteen percent of the TIKA global aid budget goes to the Western Balkans – hardly enough to make a difference in these economies. But it is a huge source of pride for the Turkish government that TIKA provides aid to communities in the Middle East, the Balkans, and Africa – showcasing Turkey as a great power in a position to help the needy around the world. This is a constant theme in pro-government media and in political speeches. TIKA’s efforts to renovate Ottoman mosques, bridges, and buildings overlap with the AKP’s interpretation of Ottoman history – the empire as the mighty, benevolent, and fair power that provides goods and services to its subjects to improve their lot.

This self-image has been the predominant theme in the AKP’s political campaigns in recent years. As such, AKP leaders and media outlets that support the party depict Ottoman conquests in the Balkans as part of a civilising mission, and would like contemporary Turkey to play a similar role in aid, development, and reconstruction there. This, AKP intellectuals argue, sets the Ottomans apart from Western colonial powers who want to conquer and exploit the under-developed regions of the world. For example, in a recent television interview about his newly published book, The Barbarian, the Modern, the Civilised: Notes on Civilisation, Ibrahim Kalin, Erdogan’s spokesman and chief foreign policy aide, went to great lengths to describe the Ottoman contribution to Balkans communities and civilisation. His book compares the Ottoman contribution to civilisation to the supposedly more savage and inhumane Western model. During the interview, Kalin took great umbrage at the interviewer when he suggested that people in places such as Serbia might have a different take on the Ottoman past. Ottomans were not imperialists, he argued.

In a country where a significant part of the population has roots in the Balkans, this type of grandstanding works beautifully to recast Erdogan as the man who is restoring the empire to its former glory and helping the needy around the world. AKP supporters are proud of this image and have rewarded the party in the past decade following campaigns that reinforce the image of Turkey as a great power. In reality, however, Turkey’s political and economic outreach is very limited. TIKA is the only instrument for Turkey’s contribution to the economic development of these regions. The country’s support for local projects is, at best, very limited – and certainly cannot be compared to the funds and accession aid that Brussels is able to provide.

Economic ties

As part of the Turkish president’s pragmatic reset of relations with the Western Balkans, Ankara has identified the region as presenting significant opportunities for Turkish influence and economic activity. In Turkish strategic thinking, the Western Balkans is an arena of great power competition that has not been claimed by any one power. Turkish officials stress that there is an opportunity for Turkey to strengthen its economic presence in the Balkans, reasoning that China is not yet fully present in the region despite displaying a keen interest in it, that the Russians are mostly posturing, and that Europe is too distracted to fully focus its efforts there.

The Turkish government also recognises that the region has major infrastructure and privatisation projects up for grabs. Mehmet Ugur Ekinci of SETA, a think-tank with close ties to the Turkish government, expresses this view publicly: “Western Balkans countries that have not joined the EU have significant infrastructure needs. These countries have neither the internal highways and railways nor adequate port systems. Because of the lack of infrastructure, foreign investments are slow to come, impeding the development capacity of the region”. There is a perception in Ankara that Turkish businesses are more flexible in adapting to tough conditions in the Balkans than their European counterparts. The feeling can sometimes be mutual. In 2018 the head of the Serbian chamber of commerce, Marko Cadez, said: “Turkish investors go to underdeveloped areas, unlike investors from Western countries.” Twenty Turkish plants and facilities in various industries opened in Serbia in 2017.

Through various chambers of commerce and investment boards such as the Foreign Economic Relationship Council, Turkey has actively encouraged trade and investment in the Balkans. Given the increasing personalisation of relations under Erdogan, it is no surprise that he makes a point of inviting major contractors and business representatives on his trips, and Turkish leaders often attend the opening of major Turkish investment projects in the region.

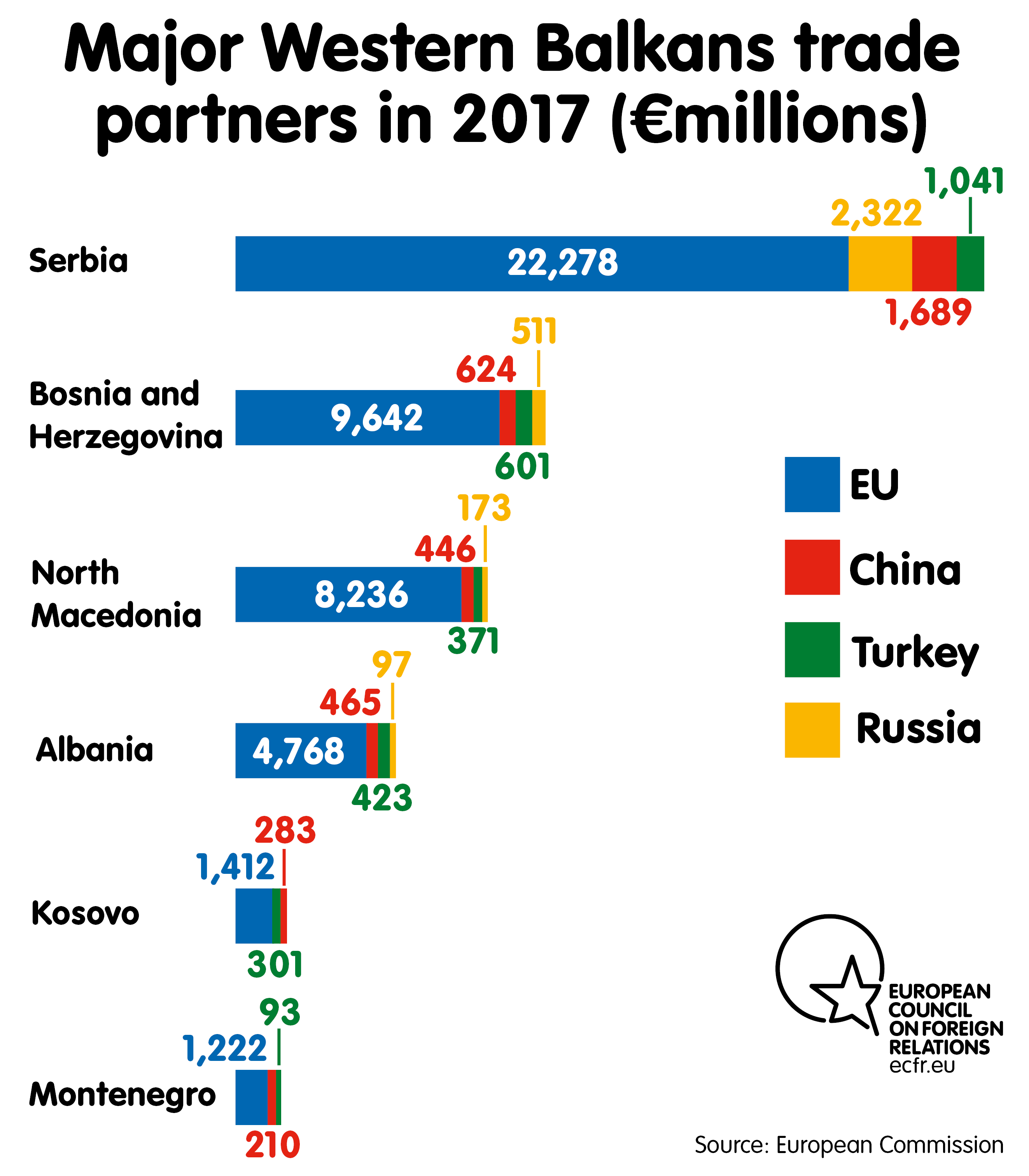

Turkish investment in the Western Balkans has been increasing steadily since the mid-2000s. What was $3.6 billion in trade in 2002 had soared to $16.2 billion by 2016, peaking at $20 billion in 2014. Turkish exports to the region amount to $10 billion, one-third of which goes to Serbia. Meanwhile, in the past decade, medium-sized Turkish companies have pursued direct investment opportunities in telecommunications, construction, transport, and finance in the Western Balkans.

Turkish contractors are also involved in various regional infrastructure projects, including the construction of a highway between Serbia and Bosnia, the construction of the new Pristina airport, Kosovo Electricity Distribution Company, and privatisation of coal mines. A Turkish consortium bought a share in the Albanian telecommunications company after its privatisation in 2007, and Turkish Airlines bought 49 percent of Bosnia’s B&H Airlines. Turkish companies and banks – notably, the government-owned Halkbank and Ziraat bank – are active across the Western Balkans; there are now 33 branches of Halkbank in Serbia alone.[8] TIKA provides millions of dollars in micro-financing to businesses in the region. Turkish entrepreneurs have established their own brands and companies across the region.

A “the Turks are coming!” sentiment, mixing amusement with apprehension, remains common among European officials who follow economic developments in the Western Balkans. But the actual data do not support the idea of a major Turkish expansion there. With the Western Balkans a growing market for Turkey, the AKP government is determined to continue making inroads into Serbia, Albania, and other parts of the region. The value of Turkey’s trade with Serbia exceeded $1 billion in 2018, but its trade with the EU stands in the vicinity of $14.5 billion. Turkey still lags Europe as an economic actor in the region on every possible measure.

Gulenism

An important subplot to the story of Turkey and the Western Balkans is Ankara’s pursuit of Gulenist fugitives and community leaders within the region. The government is engaged in a relentless global pursuit of the Gulen movement, a former ally that the AKP considers to be behind the failed 2016 coup attempt in Turkey. While seemingly inconsequential from the viewpoint of foreign policy, this pursuit is high on the agenda of Erdogan and state security services.

The Balkans has long been an important centre for the Gulen movement. For a much of the AKP’s rule, Gulen schools and universities in the region received active support from the Turkish government. These schools typically have a good track record, provide Western-style education with a Turkish bent, and, in the case of Bosnia and Albania, are attended by the children of the elite. But, since the failed coup attempt, Ankara has, with limited success, pressed Western Balkans countries to extradite Gulenists and close down Gulen-linked institutions. Turkish diplomats confirm that government directives instruct them to prioritise the pursuit of Gulenists in Western Balkans countries.[9] In March 2018, the Turkish intelligence agency forcibly brought six senior Gulenists from Kosovo to Turkey, leading to a political scandal that caused Kosovo’s interior minister and intelligence chiefs to lose their jobs.

Western Balkans leaders hedge their bets between the Gulen networks in their country and relations with Turkey, which is conducting an all-out war against these entities. On the night of the 2016 coup attempt, the leaders largely hailed Erdogan’s actions. Rama tweeted: “Happy for the brotherly Turkish people and our valuable friend, President Erdogan, for going out with full success from a very difficult night”. Bakir Izetbegovic wrote: “My message to my brother Erdogan is that he has strong support here, amongst us in Bosnia.”

However, Western Balkans states have hesitated to shut down or close in on Gulen networks – which includes schools whose good reputations have likely helped protect them, as well as governments’ concern for rule of law issues during the accession process with the EU. On balance, the fact that Western Balkans countries, including Bosnia, have not moved to close down Gulen schools has been a disappointment for Turkey. The Turkish government is not satisfied with their response and continues to demand further action. The Turkish authorities closely monitor the activities of the Gulen movement in the region.

From Macedonia to Albania, the Western Balkans is a major battlefield in Erdogan’s fight against Gulen. And it will continue to be in the coming years. Meanwhile, Ankara is trying to promote its alternative to Gulen schools, called Maarif foundations. Maarif schools provide a mix of regular classes with conservative Islamic teachings. The Turkish president supports their expansion in the Balkans, and there are already Maarif schools in Bosnia, Macedonia, Kosovo, and Albania – though they have not yet achieved popularity abroad. In 2018 Turkey’s supreme court ratified a decision to transfer all Gulen-linked schools in Turkey to Maarif.

Conclusion

Turkey’s influence only extends so far: the half-hearted Western Balkans response to Turkey’s pursuit of Gulenists is emblematic of its strength in the region. The country certainly has a presence there – but there are limits to it. Despite internal propaganda in Turkey, and despite exaggerated fears in Europe of some sort of a revanchist Turkish return to the Western Balkans, Turkey has not become a regional hegemon. With the exception of popular Turkish soap operas and the occasional renovated building, there is no prospect of any form of neo-Ottoman empire there. There is also little to suggest that Ankara is trying to spread its increasingly illiberal governance model, which remains highly controversial in Turkey.

In a recent debate between opposition and government members of the Turkish parliament, Celal Adan – representing the ultra-nationalist Nationalist Action Party, a close ally of the government – said: “First of all, no one can say anything to the Balkans, to the Balkans Turks [Muslims]. No one can politicise this topic. Balkans is where we breathe oxygen. Let’s be frank about that.” This suggested that there was a broad national consensus on improving relations with the Balkans, while identifying the region as one of the few zones in which Turkish foreign policy could “breathe”.

This is a revealing admission. Turkey’s ruling elite feel the Balkans is perhaps the only part of an unfriendly universe where Turks can develop good relations and exert some power in their neighbourhood (“oxygen”). The Balkans is a feel-good arena for Turkish foreign policy at a time when it has run into roadblocks in its relations with the US, its accession process with the EU, and the war in Syria. Turkey does not directly involve itself much in the internal political dynamics of the region but does want to project Turkish power there, even if it is limited.

So where do developments since 2002 leave Turkey and its relationship with the Western Balkans? Turkey may spy economic opportunity in the region. But, in terms of the broader geopolitical situation, it is not seeking to reshape it, or to yank it out of the European framework. It would like influence, but the transatlantic security architecture, of which Turkey is a crucial part, remains Ankara’s preferred framework.

In places where great power competition between the West and Russia is apparent – such as Ukraine and, indeed, the Balkans – Ankara has so far stayed within the Western consensus. This, however, could change if, in future, Turkey’s place in NATO – traditionally its main anchor in the transatlantic community – looks liable to change. The real danger for European interests in the Balkans is not Turkey itself, but a Turkey outside the architecture of the West.

Tensions between Turkey and the US have emerged since the failed coup of 2016, and the fate of Gulen – who is resident in the US – also adds significant complication to the relationship. But, unlike in the Middle East – where Turkey is willing to use coercive military power and to freelance on security – in the Balkans, it is still in the country’s interest to promote NATO partnership and EU enlargement. Both promise to provide economic and political stability to the region. As an immediate neighbour and a trading partner, Ankara supports NATO- and EU-backed stability.

Indeed, Europeans sometimes ask: “Can Turkey be a spoiler for Macedonia’s NATO accession bid?” The answer is another question: “Why would it?” So long as Turkey is a NATO member, it will not see such an expansion into the Western Balkans as a threat. It has already been supportive of Macedonia and other countries entering multilateral transatlantic institutions. Through NATO and partnership programmes, Turkey has developed closer relations with military leaders in these countries.

However, if Turkey’s position within NATO came under strain because of increasing tensions with the US, Ankara’s stance on NATO enlargement in the region could change – towards apathy or a hands-off attitude towards the Russian role in the region. Turkey’s outlook in the Balkans does not depend on developments in the region but on how Ankara navigates its relations with Washington – and how it defines its role in the West. Turkey’s recent bid to purchase Russian-made S-400 surface-to-air missile systems and the strong US objection to this may be that defining moment in its relations with the transatlantic community. Ankara’s desire to work with Moscow in Syria has also led Erdogan to opt for Russian hardware, throwing Turkey’s NATO partners into a dilemma over how to respond.

The Trump administration has offered to sell an alternative system – US-made Patriot batteries – to Turkey, while Congress is threatening to slap sanctions on Turkey, including those that would expel it from the F-35 fighter jet programme if it purchases the Russian system. How this story unfolds in the next few months will have a huge bearing on Turkey’s external relations, including its alliances in Syria. It will also have an impact on Turkey’s adherence to transatlantic norms in the Balkans.

A similar situation obtains with EU enlargement. Turkey has been in accession talks with the EU since 2005 and has looked favourably upon the idea of enlargement. Turkish influence in the Western Balkans does not run counter to Europe’s enlargement agenda and the EU accession process is the best instrument for achieving the kind of internal stability that Turkish businesses and defence doctrine need. In interviews conducted for this paper, no Turkish official positioned Turkey as an alternative to the EU – but several expressed disappointment that Western Balkans nations are on a faster track than Turkey in the accession process. They believe that, in the EU, Western Balkans countries would likely join the Turkey-friendly factions within the bloc.

To the extent that Turkey has a cohesive policy on the Western Balkans, it rests on four pillars:

- Transatlantic institutions: Since the end of the cold war, Turkey has promoted the integration of the Western Balkans into transatlantic institutions. Despite Europe’s fears and concerns with Erdogan, Turkey continues to support the expansion of NATO and the EU in the region.

- Trade: Turkey wants to become an economic player in the Western Balkans largely because the region is close to Europe, on an EU membership path, and offers opportunities and market access that European countries do not.

- Muslim communities: Preserving Ottoman heritage, renovating Ottoman-era buildings, and protecting Muslim communities across the Balkans is an important aspect of Turkey’s approach to the region. With the exception of Bosnia and Albania, Muslim populations are in a minority in Western Balkans countries. And these populations have a predominantly secular approach to Islam and religious identity – making them immune to the AKP’s appeal as a conservative party. Outreach to Muslim communities provides popular media opportunities for Turkish politicians, but the AKP’s brand of conservative Islam is not a major factor in regional dynamics.

- Erdoganism and the battle with Gulenism: Erdogan’s personal ties with Vucic, Thaçi, Bakir Izetbegovic, and other Western Balkans leaders are important both in the promotion of economic ties and in terms of reinforcing his image as a global leader back home. The region’s leaders have figured out the importance of this for the AKP’s domestic audience. They allow Erdogan seniority in symbolism in return for better relations with Turkey. The AKP’s fight against global Gulen networks and surveillance of Gulen activities in the Western Balkans continues to be a priority for Erdogan. The issue is a constant background theme in bilateral conversations. Western Balkans leaders know that Turkey values any favour to it in this very highly, so they try to strike a balance between rule of law issues and the accommodation of Ankara’s wishes.

Europe and Turkey have different priorities in the Western Balkans, but increased Turkish activity and visibility in the region do not signal that Turkey is promoting an alternative model for these states. Indeed, the expressions of nostalgia that Turkey has been prone to making, especially since the Davutoglu era, are mostly for domestic consumption. So long as there is a European membership perspective for Western Balkans countries, Turkey’s political influence will remain secondary. So long as Turkey has an EU perspective – however dormant its accession process may be – Ankara will continue to support EU enlargement in the Balkans. Western Balkans capitals are not looking to change their countries’ destination. Indeed, European policymakers should understand that, from Ankara’s point of view, the entry of friendly Western Balkans nations into the EU would be a boost to the pro-Turkey camp there. Turkey also sees enlargement in the Western Balkans as a way to guarantee the safety of Muslims in the region.

Having understood their Turkish counterparts’ viewpoint, Europeans should take steps to include them in the development of Western Balkans countries, and to involve them in multilateral activities in the region, particularly those pertaining to EU enlargement. Turkey and Europe share many interests in the Balkans – the proliferation of transatlantic institutions, the prevention of Islamic radicalism, law enforcement, and free trade. “What is good for the EU is likely to be good for Turkey too” is not a bad rule of thumb. For example, Turkey could contribute positively to the border dispute between Kosovo and Serbia – including in their proposed “land swap”, which it already supports. Turkey could yet emerge as a stronger counterbalance to Saudi-funded Salafist movements in the region. And opening a Turkish-European dialogue on the Western Balkans could provide a much-needed boost to Ankara’s beleaguered relations with Europe.

An ever-present force in the region is that of Russia. Strengthened personal ties between Erdogan and Putin have allowed Turkey to carve out new options for itself, ones that do not currently impinge on developments in the Western Balkans. But this could change. Turkey-EU relations remain stuck, despite the fact that they could still progress in several ways – even with a stalled membership process. Were Ankara to become further alienated from Europe, it could throw its weight behind Russian initiatives in the region, such as those that support populist parties or facilitate investments in pipelines, energy hubs, and other strategically important infrastructure. This would be a devastating blow to EU enlargement and to Europe’s transformative power in the region.

Ultimately, Europe’s would like to keep Turkey as part of the transatlantic community and maintain its support of European enlargement in the Western Balkans. Turkey’s goal of cosy relations with the Balkans could prove complementary to Europe’s transformative agenda. But to tap into that possibility, Europe needs to stop hyping Turkish influence in the region and consider working with Ankara as a partner.

About the author

Asli Aydintasbas is a senior policy fellow with the Wider Europe programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations and an expert on Turkish domestic and foreign policy. Prior to joining ECFR, Aydintasbas had a long career in journalism including working as a columnist at Cumhuriyet and Milliyet, and hosting a talk show on CNN Turk. She has frequently contributed to publications such as the New York Times, Politico, and the Wall Street Journal, and she still writes a Global Opinions column for the Washington Post. Much of her work focuses on the interplay between Turkey’s internal and external dynamics. Aydintasbas is a graduate of Bates College and has an MA from New York University.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Vessela Tcherneva and Jeremy Shapiro at ECFR for convincing me that I would be perfectly capable of writing on Turkish policy on the Western Balkans – even though I am not a Balkans expert. It was an interesting journey and important for understanding the puzzle that is Turkish foreign policy. Sinan Ulgen, Birgül Demirtas, Ilija Vojnovic, and several unnamed Turkish diplomats, officials, and academics have helped expand my knowledge of the region. Many thanks to Adam Harrison for his diligent editing and to Tania Lessenska for the research on Turkish trade with the Balkans. Thanks to Nicu Popescu and Joanna Hosa and other colleagues at ECFR for their continued support.

[1] Interview with senior EU official, Ankara, November 2018.

[3] Interview with senior Turkish foreign ministry official and presidential adviser, Ankara, November 2018.

[4] Birgül Demirtas, “Turkey and the Balkans: Overcoming Prejudices, Building Bridges, and Constructing a Common Future”, Perceptions, Summer 2013, Volume xviii, p. 168, (hereafter, Turkey and the Balkans: Overcoming Prejudices, Building Bridges, and Constructing a Common Future”).

[5] Interviews with European and Turkish diplomats, 2018.

[6] Personal conversation with senior Turkish diplomat, Ankara, November 2018.

[7] Personal conversation, with Birgül Demirtas, Ankara, November 2018.

[8] Interview with Birgül Demirtas, Ankara, November 2018.

[9] Interviews with Turkish officials, 2018.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.