Europe’s digital sovereignty: From rulemaker to superpower in the age of US-China rivalry

Summary

- Covid-19 has revealed the critical importance of technology for economic and health resilience, making Europe’s digital transformation and sovereignty a question of existential importance.

- Rising US-China tensions are an additional incentive for Europe to develop its own digital capabilities; it risks becoming a battleground in their struggle for tech and industrial supremacy.

- Democratic governments – keen to preserve an open market in digital services while protecting the interests of citizens – find the European model an increasingly attractive alternative to the US and Chinese approaches.

- The EU cannot continue to rely on its regulatory power but must become a tech superpower in its own right. Referees do not win the game.

- Europe missed the first wave of technology but must take advantage of the next, in which it has competitive advantages such as in edge computing.

- EU member states lack a common position on tech issues or even a shared understanding of the strategic importance of digital technologies, such as on broadband rollout or application of AI.

Preface

José María Álvarez-Pallete López

In times of uncertainty, humanistic values must serve as the compass that sets us on the right path. The covid-19 pandemic has accelerated the digital transformation of our societies and our economies at a dizzying rate. In just a few weeks of lockdown we have seen teleworking, e-commerce, and online education advance as much as over a five-year period under normal conditions.

Keeping communications up and running has been our first and primary contribution to this health, social, and economic emergency. Indeed, Telefónica became one of the support structures that kept the business, cultural, educational, labour, and financial activity of our society alive in Spain.

Digital infrastructure has proved to be fundamental for social welfare, especially health and education, and the functioning of the whole economy. In the face of the crisis, Telefónica’s mission “to make our world more human by connecting lives” has become more relevant than ever. We have learnt that connectivity is crucial for inclusive digitalisation and, with our mission and values as our guide, this crisis has brought out the best in us.

The year 2020 will be remembered as the year of the pandemic, but also as the year when our world restarted on a new course, and there is no turning back. We have difficult times ahead of us where we will need to cope with the economic stagnation and increased inequalities that we have lived through in recent months.

Now, more than ever, we need a new Digital Deal to build a better society. The values of solidarity and cooperation have prevailed in these critical times. This should inspire modern governance models as the traditional recipes no longer work. The close cooperation and dialogue between governments, civil society, and companies is of paramount importance to reach social commitments. This Digital Deal implies defending our values without disregarding fundamental rights in this new era, and setting course for a more sustainable, inclusive, and digital society.

The main axes of this new Digital Deal should be the following:

First, inequality is the greatest challenge we face. We should ensure that most of the population has access to technology and the opportunities brought by the new digital world, reducing the digital divide. Therefore, investing in people’s digital skills is critical. Traffic on our online education platforms has grown by more than 300 per cent and 85 per cent of the jobs in 2030 do not yet exist. Reskilling and upskilling the workforce to meet the needs of the labour market and reinventing education for the digital age are essential to ensure that no one is left behind. And at the same time, social and labour protection systems should cope with the rapid evolution of the digital economy.

Second, we should make societies and economies more sustainable through digitalisation, supporting key sectors, technologies, and innovation to accelerate the green transition and the digitalisation of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and public administrations. SMEs have great weight in the economy and job creation. Thus, it is necessary to set up a digital reconstruction fund at regional and local levels, which could be used to support them in their digitisation process.

Additionally, we need to build better infrastructure. Telecommunications have been confirmed as a vital sector in contemporary societies, but they can only fulfil their role if they have the best networks. We have witnessed that having the most powerful fibre network in Europe is something essential. Hence, it is crucial to reinforce and invest in very high capacity networks, as well as to enable new forms of cooperation and facilitate wide deployment of resilient, reliable, and fast networks. Moreover, building better infrastructure also means connecting the unconnected, reducing the digital divide.

Ensuring fair competition is also of paramount importance. The roadmap of renewed industrial strategies must be fine-tuned and defined to minimise national protectionism, modernise the rules on competition and supervision of the markets, and update fiscal policies. We ask for the same rules and the same obligations for the same services. At the same time, it is necessary to design national and regional long-term strategic plans to foster the development of local industries focusing on new technologies such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, cyber security, cloud, and blockchain. These are critical for progress in digital transformation (such as fiscal incentives and the development of Centres of Excellence) to reinforce digital sovereignty.

Finally, we must guarantee an ethical and trusted use of technology, protecting privacy and other digital rights. Public administrations and companies using new technologies must apply best practice to make its use accountable and build up trust for users. People need to have the choice to manage data and control their usage. A relationship based on trust will ultimately be the basis for a new model of fair exchange of data and trusted technologies for the benefit of society as a whole.

In the future, when looking back on these challenging times we will realise that this was the moment when technology, cooperation, and telecommunications infrastructure proved to be our great allies in overcoming this crisis through innovation and solidarity.

José María Álvarez-Pallete López

Chairman and CEO, Telefónica S.A.

Foreword

Anthony Giddens

The digital revolution is the greatest transformative force in world society today, developing at a pace unseen in any previous period of history and intrinsically global. An estimated 45 per cent of the world’s population have smartphones and even more have occasional access to one. This is the first time ever that cutting-edge technology has gone en masse directly to poorer areas of the world. Combined with the impact of radio and television – themselves now largely digitalised – huge numbers of people have access to 24-hour breaking news. Social media have made a reality of Marshall McLuhan’s global village, where people form personal friendships and intimate relationships, but where there is also gossip, innuendo, deception – and violence. What is Twitter, but empty chatter? And yet digitalised it intersects deeply with power. Gossip, innuendo, and deception: these are an intrinsic part of ‘fake news’, with all its disturbing effects in politics and other domains. The global village, it has aptly been said, will have its village bullies and so indeed it has turned out to be.

Demagogic leaders can communicate with their supporters directly in ways that were never possible before – and can keep whole swathes of the population under direct surveillance. New forms of resistance, and even insurgency, however, also arise.

As contributors to this volume point out, the realities of the digital age are a long way from the early hopes and aspirations that many had with the rise of the internet. Some of its pioneers, such as Tim Berners-Lee, the major figure in the creation of the world wide web, believed that it would be above all a vehicle for collaboration and democratisation. Yet as we all now know, its dark and destructive side brooks very large too. The uprisings of the Arab Spring were the first digitally driven democratic movements and at the time they seemed to many to presage a breakthrough. The reality turned out to be much more complex and disturbing.

The advent of the digital age is often equated with the rise of Silicon Valley, but extraordinary although that is, its true origins lie in geopolitics and political power – to which it constantly returns. The origins of AI can be traced in some substantial part to the contributions of Alan Turing during the second world war. Yet the driving force of the digital revolution more generally came from the ‘Sputnik moment’. The first being ever sent into space was not a human, but a dog, Laika – a mongrel from the streets of Moscow – in Sputnik 2. The Sputnik programme was a huge shock to the American psyche. It prompted a massive response from the US government, with the setting up of NASA and ARPA (later changed to DARPA) and the pouring of hundreds of millions of dollars into research on the military frontier. The ARPANET was the first origin of what came later to be called the internet. The rise of Silicon Valley and the huge digital corporations is inseparable from the geopolitical transformations of 1989 and the unleashing of free markets around the world. They did not do the core research upon which their meteoric rise was based; and it was an artefact of a very particular phase of history.

Itself divided, Europe figures largely as a backdrop to this scenario, rather than as one of its driving forces. It is precisely this that explains the dilemmas explored in some detail in this volume. 1989 was a time of transformation in China too, and a turning-point – in Tiananmen Square. For better or worse, the reaffirmation of state power that followed was the springboard for the ‘Chinese model’ – a market economy coupled to, and overseen by, an authoritarian state, but one that in economic terms has been dramatically successful. China has its own huge digital corporations – of which Huawei is one, if by no means the biggest – but they operate within the penumbra of the state. The country now has the world’s most advanced quantum computer and is more or less at level pegging with the United States on the frontiers of AI, including its applications to weaponry.

Europe has not wholly been left behind in the coming of the digital age – after all, Tim Berners-Lee worked at CERN. Yet in the ‘new Cold War’, if that is what it turns out to be, Europe once more finds itself caught in the middle, sandwiched between the US and China, with a digitally malicious Russia standing on the side-lines. Thus far at least, the impact of covid-19 has served to deepen these divides. Its consequences could introduce a whole series of further dislocations and rivalries across the globe. The papers in this volume provide a valuable assessment of how Europe, and specifically the European Union, should respond. The full panoply of strengths and weaknesses of the union are on display and it will be not at all easy to chart a way through.

Introduction: Europe’s digital sovereignty

“Can we ring the bells backwards? Can we unlearn the arts that pretend to civilise, and then burn the world? There is a March of Science. But who shall beat the drums for its retreat?”

– Charles Lamb, 1830

Change is the idiom of our age. In recent years, change seems to have arrived at a bewildering pace from almost every direction. New political movements, newly powerful states, and novel diseases all seem at times to threaten, as in the English essayist Charles Lamb’s day, to “burn the world”. At the root of nearly all these daunting changes lies the vast opportunity and perilous promise of digital technologies. In recent decades, they have fundamentally altered how people and societies interact on every level, from how we make war to how we make love.

As a result, the questions of who owns the technologies of the future, who produces them, and who sets the standards and regulates their use have become central to geopolitical competition. Nations around the world are trying to shape the developments in new technology and capture the benefits – both economic and geopolitical – that emerge from this era of rapid change. They are, in short, seeking to protect their digital sovereignty – that is, their ability to control the new digital technologies and their societal effects.

For European policymakers, the idea of digital sovereignty is part of a larger struggle that they face to maintain their capacity to act and to protect their citizens in a world of increased geopolitical competition. On a host of issues, from Iran policy to military defence and regulating disinformation, it appears that the European Union has never been as sovereign as it thought. A time of fiercer geopolitical competition, and an America more focused on its narrow interests, have exposed the EU’s lack of independence in new ways –not least in the digital realm.

It is now clear that, if Europeans want to reap the economic benefits of emerging digital technologies, ensure their politics remain free from divisive disinformation, and decide who can know their most personal information, they will have to protect their digital sovereignty and compete with other geopolitical actors in the digital realm.

The European Council on Foreign Relations has proposed a new concept of “strategic sovereignty” that can help guide the EU and its member states through this new era of geopolitical competition. Strategic sovereignty implies that the EU and its member states need to preserve for themselves the capacity to act in the world, even as they remain deeply interdependent. Promoting European digital sovereignty is a critical piece of this effort. The purpose of this volume is to aid in that effort by helping readers understand better the challenges and opportunities that digital technologies, and the geopolitical competition over them, poses for Europe and its member states.

The contributors to this volume examine the geopolitical context in which Europe operates on a variety of issues, including 5G, cloud computing, and competition policy, and suggest ways to better protect European sovereignty. The focus, reflecting the nationality of most of the authors, is on the situation in Spain, but the lessons apply broadly across Europe. This chapter sums up the issues explored by dividing them into problems that have been around for several years, new problems that have emerged in the last couple of years, and assessing the key challenges and opportunities that the EU and its member states face in enhancing European digital sovereignty.

Continuity

Technological developments naturally focus our attention on change. But, in this whirl of dynamism, many less stirring, but no less critical, pockets of continuity often go unnoticed. Technology can engender rapid changes, but, as many of the contributors emphasise, several aspects of the struggle for digital sovereignty have already been with us for several years and we can expect that they will continue to shape that struggle for many years to come.

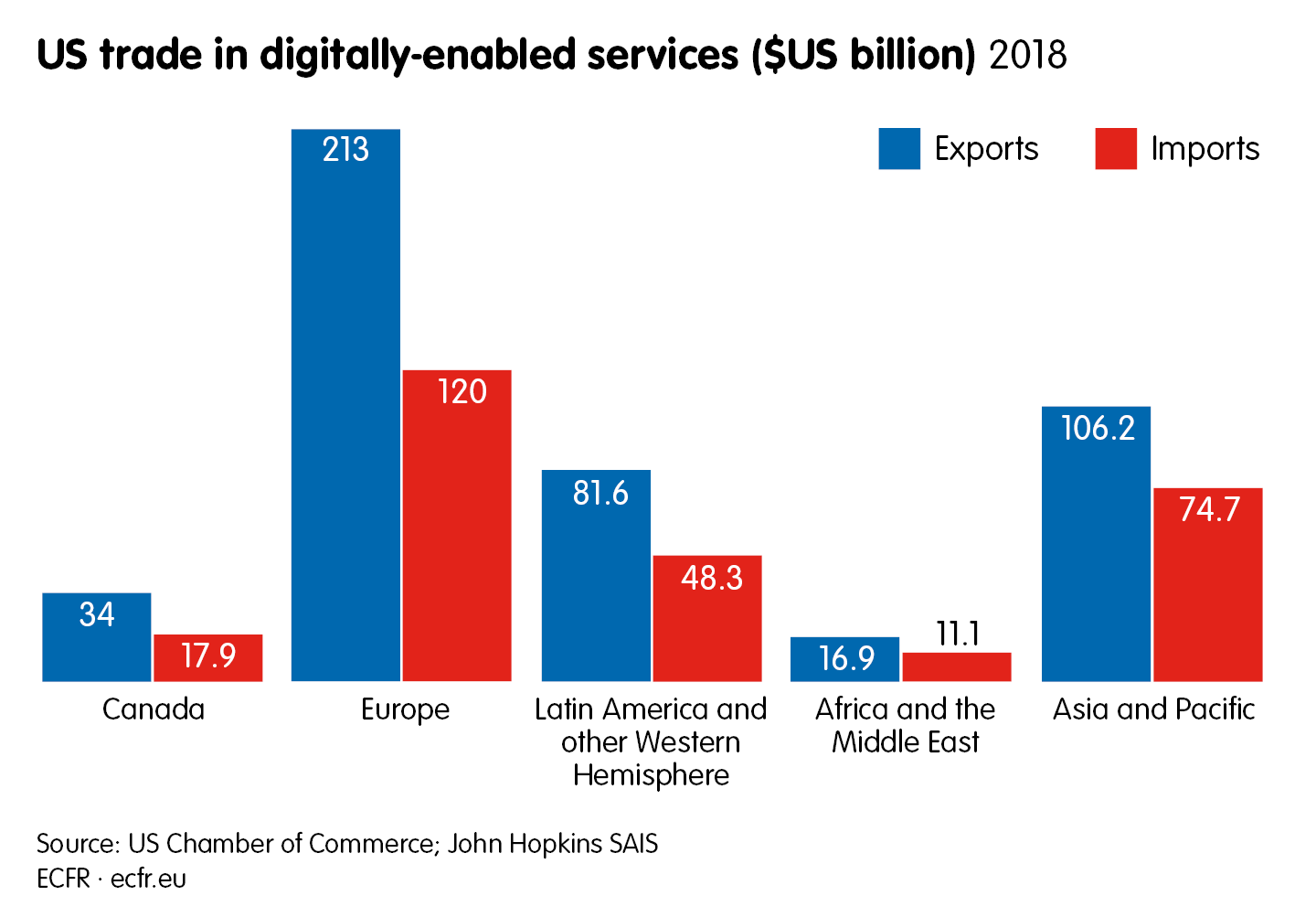

The first concerns the continuation of the bipolar competition between the United States and China that is undermining international cooperation, particularly on technology issues. Nearly all the essays underline that this conflict will likely persist, and indeed that US-Chinese relations, particularly on technology issues, will continue to deteriorate. As both Fran Burwell and Janka Oertel show, the pandemic has exacerbated existing divisions between the US and China. Most of the authors see their burgeoning conflict as framing the European struggle for digital sovereignty. Europe remains digitally dependent on both the US and China in a variety of domains, from chat platforms to telecommunications equipment. Competition between the US and China means that both sides increasingly see the European market as a critical battleground in the larger struggle to establish their global technological and industrial dominance. Europe, in Oertel’s words, is already “caught in the crossfire”. As recent political debates within Europe on issues as diverse as 5G technology and internet regulation demonstrate, US-Chinese rivalry is starting to impinge on practically every technological issue.

The second area of continuity concerns the capacity of digital tools, particularly social media, to spread disinformation and undermine democratic institutions. As José Ignacio Torreblanca points outs, the coronavirus crisis has only highlighted the degree to which both foreign and domestic actors can use a combination of digital technology and social psychology to pursue a variety of political agendas, including disrupting democratic processes and exacerbating domestic political polarisation. The growing awareness of this problem has not yet lessened its prevalence and we should expect conflict within societies over how to regulate digital content. The fact that, in Europe, the dominant social media companies are American means that the struggle to regulate them will have geopolitical consequences.

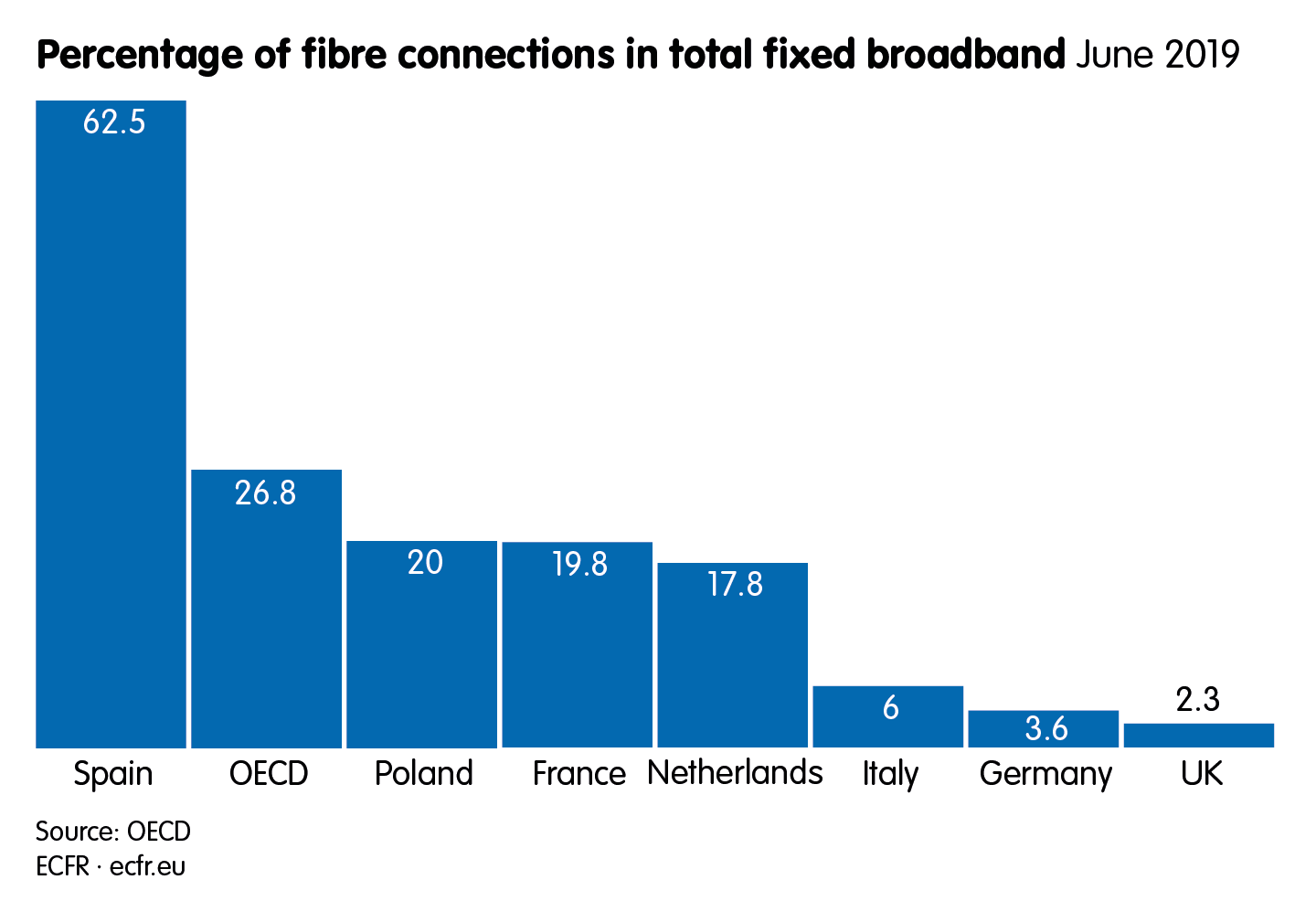

A final field of continuity concerns the persisting digital divide within Europe. As Alicia Richart emphasises, this divide does not correlate with the size or power of the state. Some of the largest and wealthiest states in Europe, such as Germany and France, lag in creating digital infrastructure, while Lithuania and Greece are among the leaders. The more critical divide is also within states: between urban areas that tend to have effective access to digital infrastructure and rural areas. Digital divides have all sorts of pernicious effects on individual lives and national solidarity. But the coronavirus also highlights just how critical digital technology and infrastructure has become in enabling countries to retain their capacity to act, particularly in crises. Spain’s strong digital infrastructure, as Richart points out, was essential to its capacity to manage the lockdown and its overall covid-19 response. Digital divides thus also threaten both European sovereignty and European resilience when the next crisis, regardless of its nature, hits.

Change

Despite these important continuities, the contributions to this volume also show some significant changes that have occurred in the last couple of years. The most salient appears to be the increasing attention given to, and activity surrounding, digital sovereignty issues by almost every level and part of government in recent years. As most self-help programmes suggest, the first step to solving any problem is recognising that you have a problem. Nearly all the essays, and particularly those by Torreblanca on disinformation, Andrew Puddephatt on internet governance, and Ulrike Franke on artificial intelligence (AI), document an increasing recognition that digital technology has become a critical battleground in geopolitical struggles. This seems almost a banal point given the constant drumbeat of news about cybersecurity and disinformation. But it is important to recognise that as recently as 2016, the idea that Europeans needed to understand, say, social media platforms as a source of national power remained controversial.

Concerns about digital sovereignty mean that digital competition is no longer just about economics. This realisation has given rise to a re-evaluation of Europe’s digital competitors. The biggest change in thinking about digital sovereignty surrounds the increasing concern about the US abuse of its dominant digital position. As Andrés Ortega Klein notes, there is a growing sense of a “neocolonial” dependence on US internet companies. European efforts to, for example, impose a digital tax, fine large American technology companies for anti-competitive practices, and consider new industrial policies to foster European champions in key areas all reflect this growing discomfort.

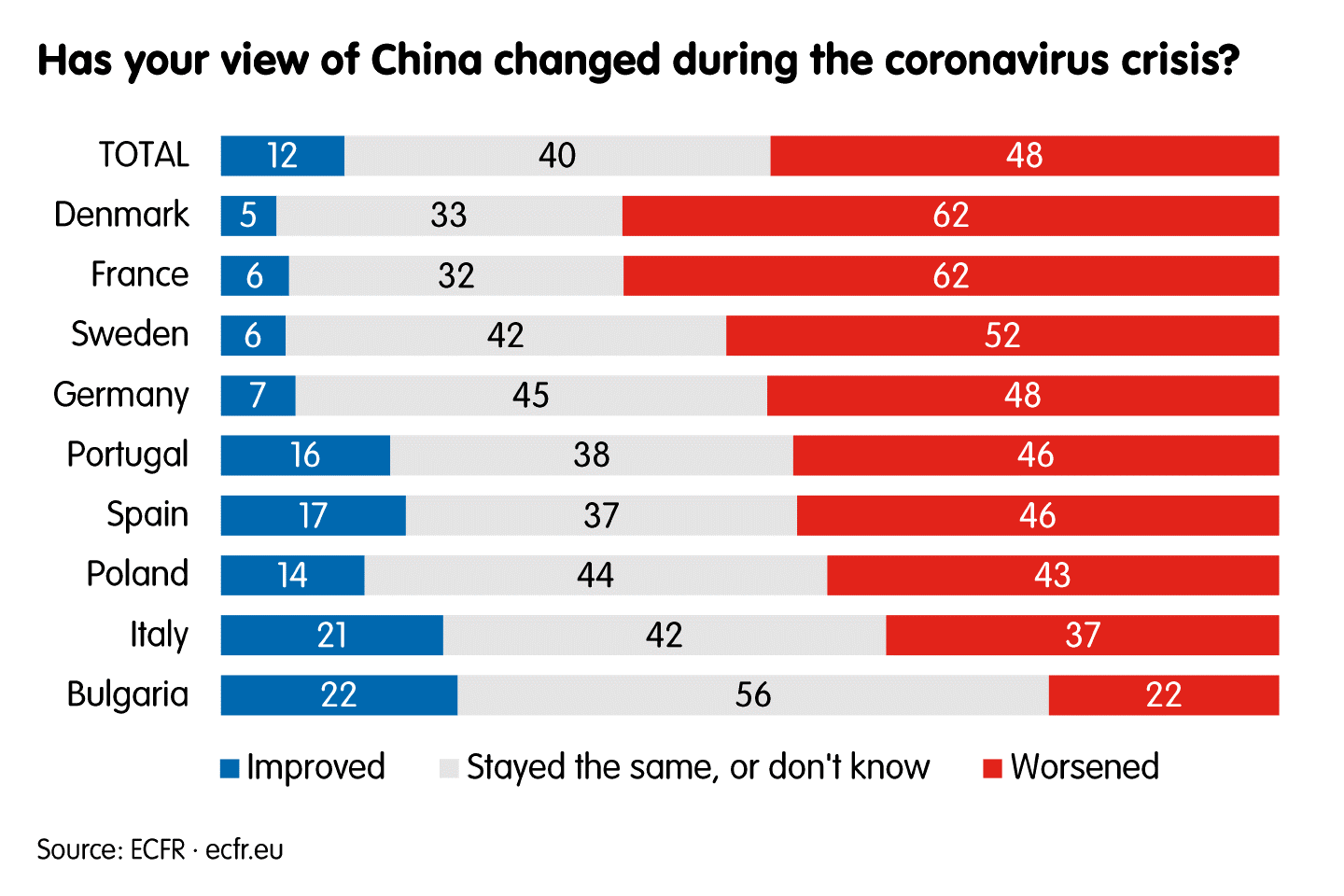

This reliance on the US, at least to date, far exceeds European digital dependence on China. But the essays outline an increasing wariness of China as both an economic and political competitor in the digital realm. If, from a digital sovereignty perspective, the US is the biggest problem, China has become the biggest fear. As Ortega points out, China is increasingly interested in the European market and has been persistently moving up the value chain. China now challenges European (and US) companies in virtually every high-technology sector. But, as Oertel notes, the Chinese have begun to wear out their welcome in Europe. The European-Chinese relationship was deteriorating rapidly even before aggressive Chinese diplomacy during the coronavirus crisis added to the troubles. Chinese finance and equipment remain attractive and cheap. But new efforts at investment protection and recent attempts in the United Kingdom and Germany to revisit the issue of allowing Huawei equipment into the 5G network, for example, demonstrate a heightened concern that China will threaten European digital sovereignty.

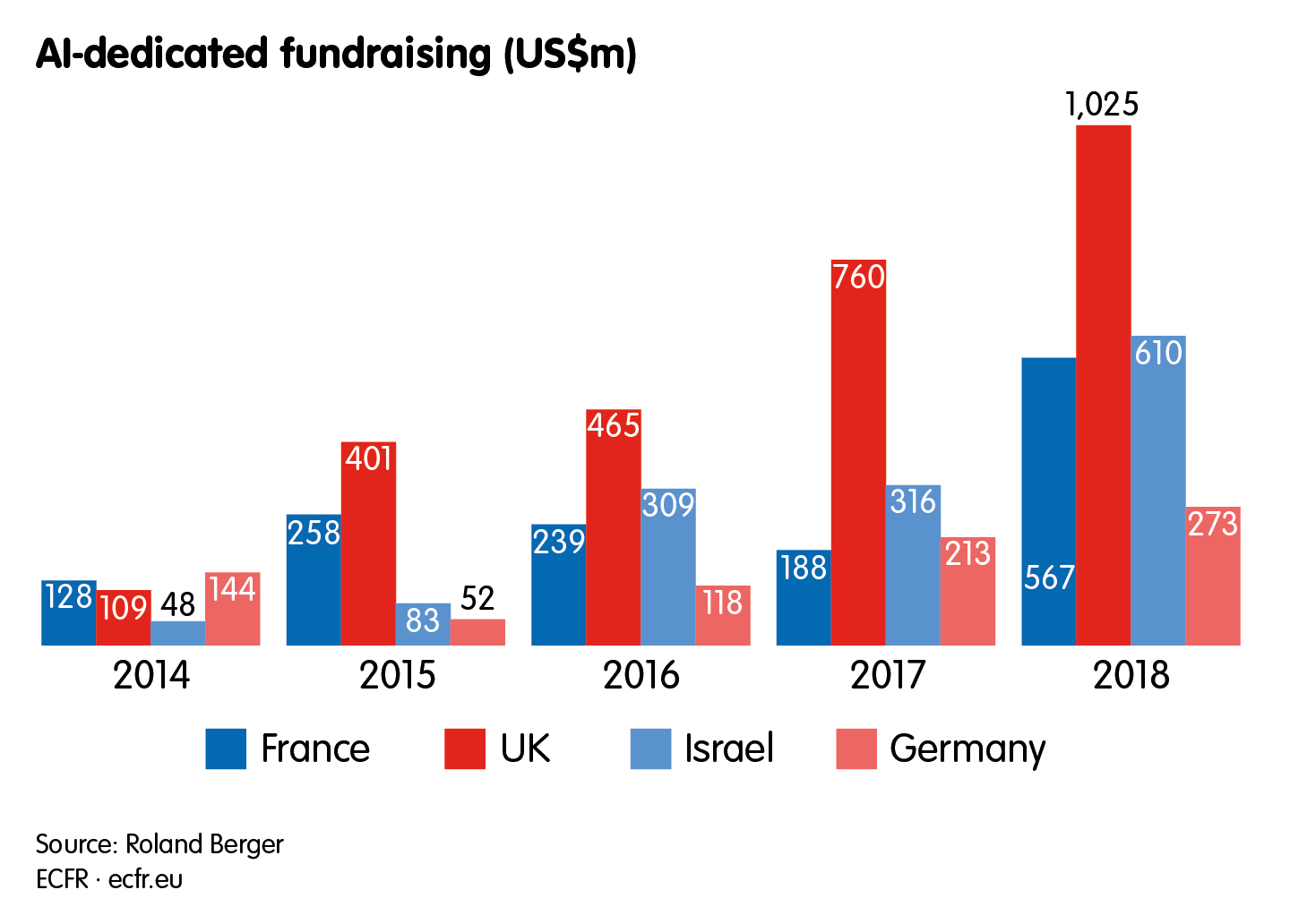

This re-evaluation of the problems that both the US and China present for European sovereignty has also led to a new way of thinking about future technology, particularly with regard to AI and the next generation of telecommunications standards. Both Franke and Andrea Renda note that many EU member states have recently become convinced that AI represents both a threat and an opportunity for European digital sovereignty. Renda speculates that, even if European companies missed taking advantage of some recent commercial opportunities for new technologies, this new awareness means that Europe is well positioned for the next wave of technology. European companies have competitive advantages in some next generation technologies such as edge computing, which distributes processing power and data storage closer to the locations where they are needed. It is a useful reminder that, for example, after the fight over 5G is over, there will be a new battle over 6G.

European challenges

Both the changes and the continuities point to some clear challenges for Europeans in protecting their digital sovereignty.

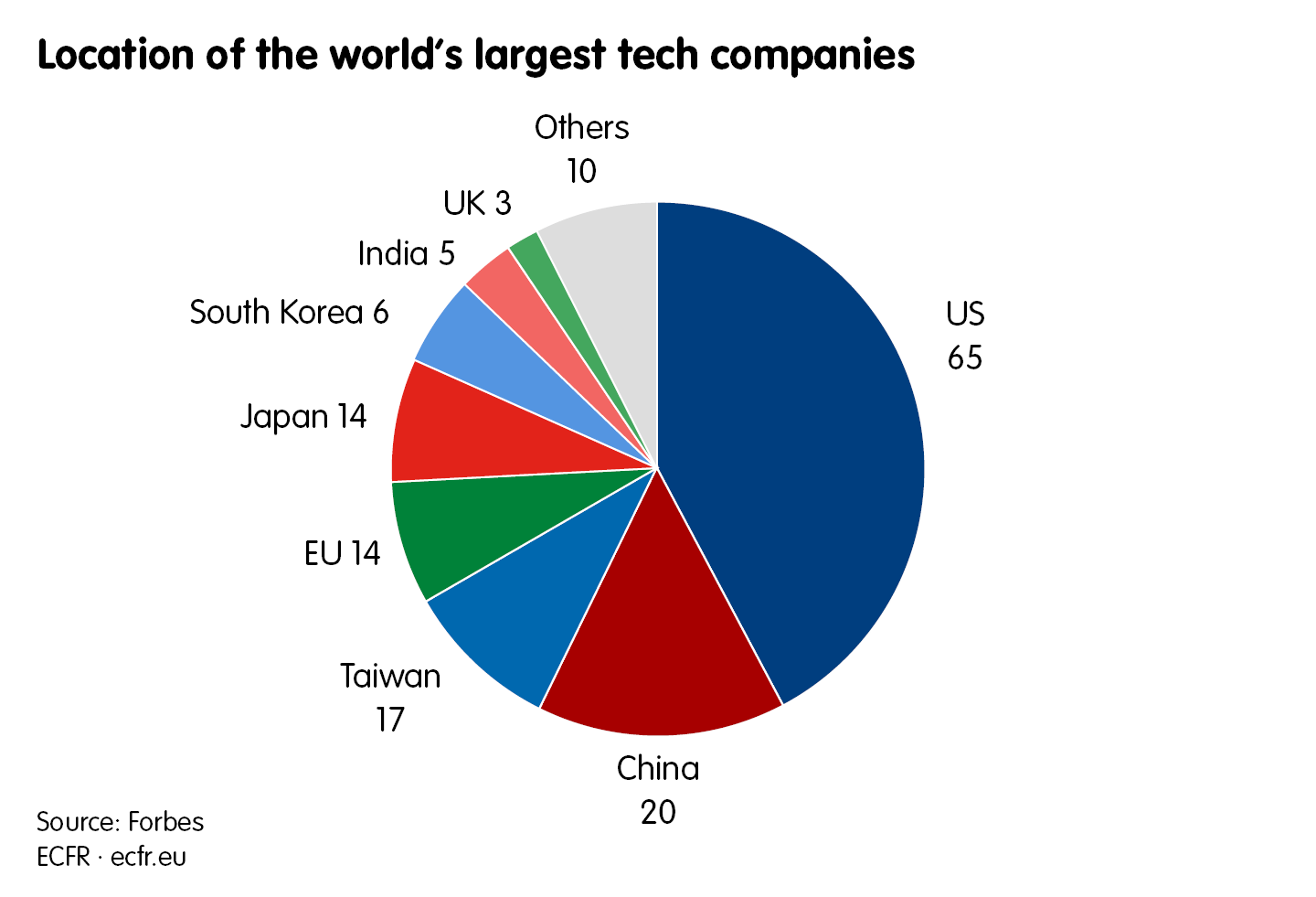

As nearly all the contributors point out, a key European disadvantage lies in the lack of significant European digital corporations with global influence. Despite Europe’s advanced digital capabilities, there is no European Google or Tencent. The increasing geopolitical competition over tech issues has made clear that this lack of national champions represents a big disadvantage in the struggle for European sovereignty. That said, it is much less clear what to do about it. Past efforts to create European champions have often turned into white elephants.

Part of the answer might lie in recognising that Europe also faces a challenge in reconciling the liberal impulses of the single market with the new struggle over digital sovereignty. One of the reasons that Europe lacks digital champions is that promising companies often get bought up by larger foreign competitors on the open market. Moreover, as both Ortega and Oertel point out, foreign takeovers of European companies allow Europe’s digital competitors access to both European technology and digital infrastructure. The continuing wave of efforts to regulate foreign investment at both the European and member-state level testifies to an awareness of the problem. But the difficulty of implementing those efforts in a way that does not descend into protectionism, and that preserves the intra-European competition that is at the heart of the single market, demonstrates how far the EU and its member states must go.

The final challenge for Europe is a familiar one and is implicit in almost all the contributions, though only Torreblanca really focuses on it. It is that, when it comes to technology issues, it is not clear that there is a European position or even that most member states want one. The differing approach and positions on regulatory issues, such as content regulation, not to mention intra-European competition for high-tech jobs, means that the EU starts at a disadvantage in competing for digital sovereignty with more coherent political actors such as China or the US. On the other hand, it is clear that, in comparison to its rivals, there is a European approach to issues such as privacy of data. And, as Ortega, Oertel, Franke, and Richart agree, if they work together, EU member states can vastly increase their global influence to push that common approach. The need to find a delicate balance between the compromises needed for a common position and the need to protect the particular interests of various member states will certainly continue to challenge European policymakers.

European opportunities

While these challenges are certainly daunting, the contributors also highlight several opportunities, both technological and political, that Europeans bring to the struggle to retain digital sovereignty.

As many of the authors emphasise, the EU’s clearest opportunity is to exercise its regulatory power to shape the international environment on digital issues. Regulatory power refers to Europe’s capacity to leverage access to the EU market, and its developed framework for creating and enforcing regulations, to encourage other states to follow European practice. In the digital realm, the most prominent example of this effort is GDPR (the General Data Protection Regulation), which has forced companies around the world to comply with European practices on privacy and encouraged similar regulations in other jurisdictions, including in various parts of the US. Franke suggests that a similar opportunity exists to exercise regulatory power in the area of AI. She suggests that a focus on creating a European regulatory framework for ethical AI could both inspire others to emulate it and force compliance with European ideas of how to control this industry of the future. Torreblanca argues that Europeans have a similar opportunity to lead in the regulation of digital content.

More controversially, some of the authors suggest that the EU also has an opportunity to use its competence in competition policy to gain an advantage in some key emerging technologies. Renda, for example, notes that the coming shift from cloud-domination to distributed data governance, in which the rules for data management are established in the jurisdiction where the data resides, give the EU a competitive edge. Similarly, Richart sees an opportunity to use forthcoming advances in edge computing to bring storage and data flows under European regulatory control. As noted, the record on this type of industrial policy in Europe is very mixed, but the realisation that Europe’s digital sovereignty is at stake has inspired a new willingness to experiment.

Finally, some of the authors even see an opportunity in the deepening US-Chinese competition over technology issues. The stark differences between the anarchic US approach to digital regulation and the heavy-handed state control model advocated by China opens a vast middle ground for European actors. Both Oertel and Burwell note that this might provide an opportunity for European actors to serve as a mediator in US-Chinese disputes. The role of mediator sits uneasily with the idea that Europeans have their own approach, but, of course, clever use of the position also provides the chance to shape the outcome. Mediation, however, would not usually imply equidistance between the US and China. For all of the complaints about US behaviour in the digital realm, Oertel, Burwell, Renda, and Torreblanca all express deep scepticism about the EU’s ability to find the type of compromises with China that it often manages with the US. Although Ortega and Puddephatt appear somewhat more optimistic about working with China, even they indicate that its authoritarian model will pose some serious limitations.

No going backwards

Alas, there is no one to beat the drum for the retreat of digital technology. The competitive struggle for digital sovereignty is thus Europe’s – and everyone’s – fate. We are marching, for better or worse, to an ever-more digital future, likely full of smarter AI, faster communications, and more sophisticated disinformation. This collection of papers represents an effort to come to terms with that ineluctable fact, but also to realise that it offers Europe opportunity as well as peril. Europeans cannot stop marching, but with some careful thought, difficult political compromises, and wise leadership, they can shape a European digital future.

Governing the internet: The makings of an EU model

Andrew Puddephatt

In February 1958, US President Dwight Eisenhower set up the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) in response to the Soviet’s Union launch of Sputnik 1 the previous year. The organisation’s mission was to make investments in technologies that strengthened national security. Its research into communication systems that could survive a nuclear attack led in 1966 to the creation of ARPANET. Whereas previous communications relied on circuits – dedicated end-to-end technology, such as telephone lines – ARPANET used packet switching. This allowed the system to break data into packets and transmit it via different channels, before reassembling it at the destination point. ARPA developed the transmission control protocol (TCP) and the internet protocol (IP) to determine how data should be broken up, addressed, transmitted, routed, received, and reassembled. The application of these protocols to radio, satellite, and other networks established a system in which data moved through very different media. The term for the approach, “inter-networking”, was soon shortened to “internet”.

One of the key characteristics of this new technology was that its configuration was determined not centrally but by the network provider. Individual networks connected to one another through a meta-level “internetworking architecture”, despite the fact that they had been separately designed and had their own interfaces. In contrast with earlier state-based mass communication systems (such as newspapers, radio, and television), the internet functioned without the need for national or global coordination. As such, internet governance initially seemed unnecessary. Although the internet operated according to rules, they were widely thought of as functional rather than normative due to their technically complex nature.

By the mid-1980s, the internet supported a growing community of academic researchers and developers. It functioned as an informal arrangement between groups of like-minded people who were willing to cooperate to build and develop the network. However, as it grew beyond a few universities, the network needed some management (to create and allocate new addresses, for example). At this stage, the administration of the registries of IP identifiers (including the distribution of top-level domains and IP addresses) was performed by one person – Jon Postel, who was based at UCLA. As his workload became unmanageable, with more countries beginning to utilise the technology, a new system was required. And, as the internet grew into a global network, it became apparent that there was a need for a minimum level of universally accepted technological standards.

Since its inception, the technical governance of the internet had operated outside direct government control – although, in practice, US-based engineers and US-based companies had de facto authority in developing its engineering protocols. Until 1998, internet governance had not been a political issue in Europe. But this changed when the US government pushed successfully to establish the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), a private non-profit organisation that took over Postel’s role in managing domains. Governments across the world began to take a view on the issue.

For the US government, it was crucial that the internet was governed by a set of non-governmental and private organisations through ICANN. Washington preferred a market-orientated solution that involved private sector self-regulation of the internet (which protected US economic interests). By contrast, the European Union argued for a public-private system in which governments had an important role – a multilateral institutional framework. China, Russia, and other countries wanted a solely state-based system of internet governance, preferably one anchored in the United Nations. The EU eventually supported the broad US position but secured a role for governments in the institutional structure of ICANN, ensuring that Europeans joined the organisation’s committees.

However, such technical arrangements were only one aspect of internet governance. Policy issues were more challenging. As the power of a globally interconnected communication network became apparent, governments began to realise that they were fast losing their control over communication technologies. Internet use increased exponentially, but its lack of overarching regulatory framework meant that what became known as “permissionless innovation” held sway over its development. The internet used existing telecommunications infrastructure – the telephone network – to grow organically, without the need for significant new investment (in countries where there was a robust telephone infrastructure). Anyone could plug their computer into the network and become part of the internet – firms required no permission to launch a service and had no regulatory hurdles to overcome. Accordingly, the internet grew more like an organic ecosystem than a planned network. Collaboration and consensus among providers were widely seen as the key drivers of decision-making.

The internet was born of a libertarian dream. Its early creators and advocates imagined it as a stateless space, outside of government control. Indeed, many believed that any kind of governance would destroy its character. In the early phase of the internet’s development, the engineers, technicians, companies, and users who drove the process were content to create a communicative capacity without concern for how that capacity would be used. They did not appear to imagine the harms that could arise from anonymised unrestricted free speech – such as child abuse, trolling, the harassment of minorities, and the propagation of terrorism. The culture surrounding the First Amendment of the United States, which fosters free speech and limits the liabilities of carriers, was crucial to the internet’s development. Many of the early innovators and creators of the digital world came from the US, where they could experiment without concern for future liabilities. As an English-language medium that (in most parts of the world) was only available to elites, the internet initially went under the radar of many governments that were inclined to censor and control communications.

By the early twenty-first century, a new era had begun. Governments across the world became alert to the potential disruption caused by access to digital communications, whether from text messaging using mobile phones, the creative use of social platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, the streaming of video direct to the web, or the use of the internet to bypass censorship. Governments increasingly looked for new ways to control and monitor the online space. At the same time, there were growing calls around the world for this unregulated environment to be brought under government control – calls motivated in democratic states by fear of crime and terrorism, and in authoritarian ones by governments’ desire to preserve their power.

As the internet grew in size and capability, there was a sharp rise in the capacity of states and non-state actors to use digital technologies to disrupt and control communications, and to thereby undermine democratic processes. Criminal networks exploited these capabilities and corroded trust in the online environment. Repressive regimes used hackers to disrupt pro-democracy and human rights groups. And new communication companies became increasingly powerful. As Timothy Wu has documented, all the dominant media of the twentieth century – whether it be radio, television, film, or telephony – came into existence in an open and free environment. All had the potential for unrestricted use, but all fell under the control of monopolies in time. A similar pattern emerged in the digital world. The internet faced a challenge from both public and private power – and, sometimes, a deadly combination of the two.

Although many governments decry the apparent lack of rules on the internet, there is governance online. Such governance is provided by major companies through their terms of service, community standards, and screening procedures. And corporate algorithms sort, rate, rank, and recommend users’ choices, constituting a type of market governance. So, the issue for many governments is not that the internet is lawless but that its laws are made by private companies through their codes and algorithms.

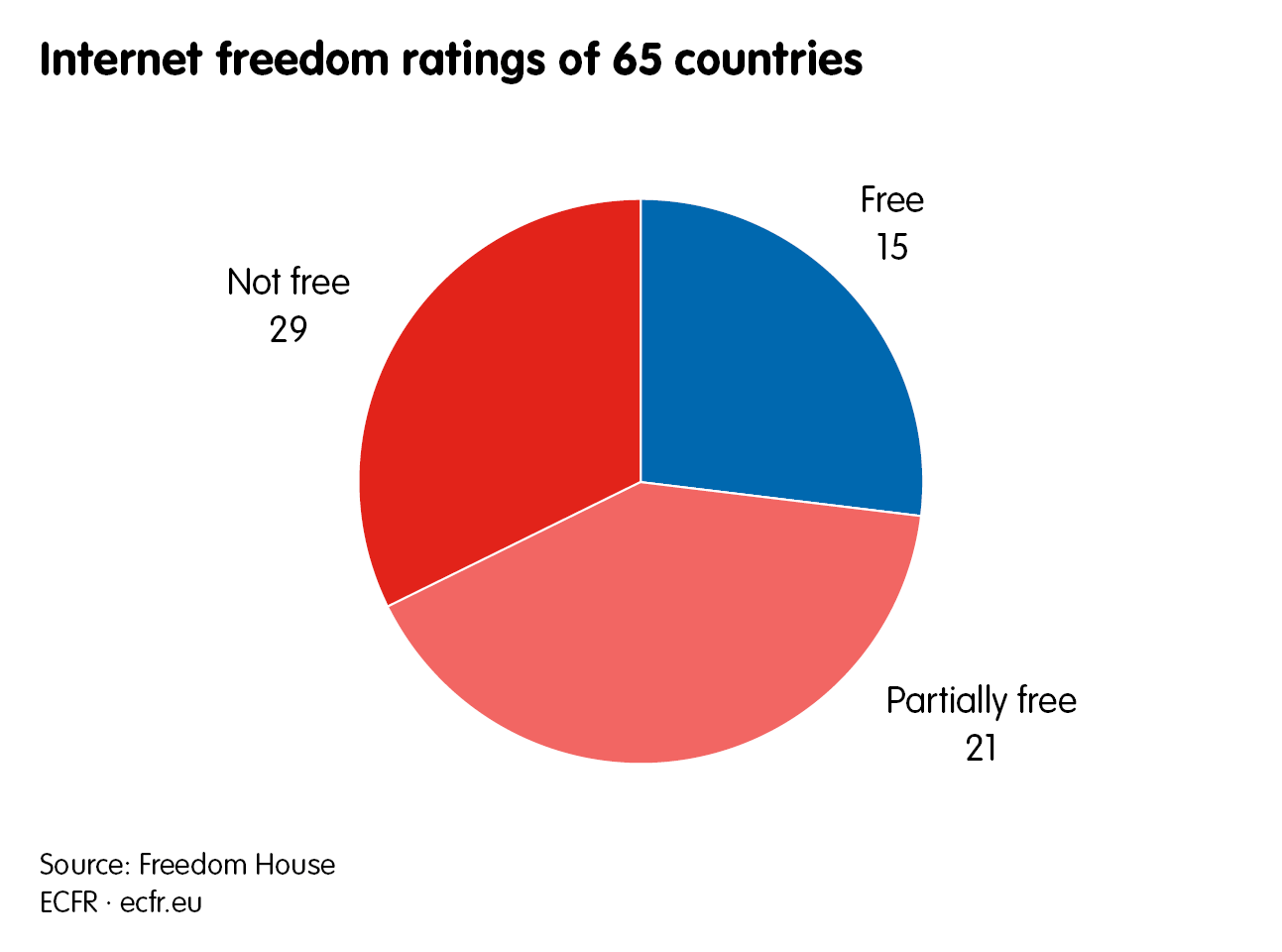

Countries such as China – which attempts to exercise total control over its domestic communications environment – reject any notion of an independent communications network outside of state supervision. The overarching goal of Chinese diplomacy is to promote the notion of cyber (or internet) sovereignty. In the words of President Xi Jinping, this means “respecting each country’s right to choose its own internet development path, its own internet management model, [and] its own public policies on the internet.” The Chinese model of the internet prioritises control through a broad range of tools and technologies that block, filter, or manipulate online content. It has rules for storing data on servers in-country, which – though Beijing portrays this as a way of limiting the power of US companies – helps the authorities access users’ information.

China’s desired goal is a long way from the US vision of a global internet run by the private sector. Beijing wants to see a series of interconnected national internets rather than a global infrastructure, with each national internet governed by the laws and values of its home state. It sees the private-led, adoptive model that has shaped the initial growth of the internet as expressive of Western, particularly US, dominance – something that is reflected in the support it receives from a coalition of technology companies and civil society groups. Chinese policymakers want the UN to play a larger role in internet governance, as they believe that they can strengthen their influence through the organisation or other multilateral, state-based forums.

Europe sits between these poles – though, diplomatically, it has usually aligned itself with the US. Internally, the EU and its member states have begun to play a major role in shaping platforms’ content rules. In Europe, a vast body of “soft law” (comprising self-regulation, dialogues, and memorandums of understanding), multi-stakeholder initiatives, and co-working forums have helped develop online content policies and practice. But there is no systematic means of incentivising platforms to assess and address problems of harm and illegality that may emerge in their ecosystems – where their commercial incentives to do so are insufficient – or of assessing the effectiveness of their responses.

Approaches to governance

The establishment of ICANN did not settle the question of global internet governance. Concerns about US domination of the internet grew with the significance of the technology. As the internet grew following the invention of the World Wide Web – to include an increasing diversity of languages and content – a small number of US companies began to dominate the services it provided (such as Facebook in social media and Google in search).

The International Telecommunications Union (ITU), a UN body whose origins lay in the development of the undersea telegraph in the nineteenth century, began to lead efforts to govern the internet in the early 2000s – which, at this stage, was mostly carried by existing telecommunications infrastructure. In response to member states’ requests, the ITU convened the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) to consider the future of global internet governance, among other things. The WSIS met in Geneva in 2003 and in Tunis in 2005. The latter event came under authoritarian influence: Tunisian government employees who posed as members of fictitious organisations dominated meetings that civil society groups had organised on its fringes. The rancour generated by this overt repression of independent voices in Tunisia undermined efforts to place governments in control of the internet. As discussed above, Washington was determined to avoid anything that suggested such control, a position that EU member states ultimately supported.

This led to the creation of the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) – a multi-stakeholder, UN-based organisation designed to provide advice or, at most, set norms. The IGF has a five-year mandate that has been continually renewed. It principally operates through its annual meeting, albeit while coordinating with working and advisory groups on other occasions. The IGF has established regional and national branches, which meet with varying degrees of participation from local organisations and companies in different countries. Its lack of formal authority was never going to satisfy authoritarian states that have pressed for a system that allows them to control the internet. Accordingly, these states rarely sent representatives to the IGF. And, over the years, high-level attendance by Western governments has dwindled. Major corporations no longer invest significant resources in the IGF, while most of its attendees are from civil society groups.

There are ongoing attempts to promote a more state-based system of global internet governance. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation – an intergovernmental organisation created in 2001 by China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan – has consistently acted as a vehicle to challenge existing internet governance models. In 2015 the organisation submitted a recommended a code of conduct on information security to the UN General Assembly. Its aim was to promote the rights and responsibilities of states in the information space, and to enhance intergovernmental cooperation by addressing common threats and challenges (which included the those posed by free speech in authoritarian states). This met with opposition from the US and its allies, including the EU.

Geopolitics has increasingly bedevilled attempts to create a global framework for managing the internet. Even on subjects such as cybersecurity – where there is common ground on the need to counter threats such as terrorism, child exploitation, and other serious crimes – it has proved impossible to reach a consensus.

Nonetheless, the concept of internet governance is far from redundant. It has mutated into a series of issues that various actors tackle in different forums. While it might have once made sense to advocate a global framework for governing it, the internet has become part of so many people’s daily lives that it affects every area of policy (a trend reinforced by the social distancing policies that have followed the covid-19 pandemic). As the internet underpins most parts of people’s working and social lives, such governance issues appear everywhere. In some areas – such as intellectual property – it may be possible to establish a global consensus. In others, geopolitics will block progress, with governance systems devolving to regional and national blocs.

One of the problems with the term “internet governance” is that it holds different meanings for different governments. For some, “governance” means “government” – a ubiquitous communication medium and a strategic asset that requires state control. For others, governance is a purely technical issue – concerning the protocols necessary to ensure that infrastructure works and evolves. For others still, governance should simply focus on mitigating the harms that arise from what is essentially a private sector medium. And then there are those who see it as a way of curbing the power of US (and, increasingly, Chinese) companies that are beholden only to domestic governments.

The EU experience

The EU has a long history of developing internet policy, albeit not in governance. Since the mid-1990s, the EU has been concerned about the potential harms caused by the internet. The EU initially emphasised soft law in its digital policy but, in the last two or three years, has shifted to a more proactive and interventionist approach. Today, the EU has the most developed policy, legal, and regulatory framework on internet issues anywhere in the world.

The EU’s power rests upon its economic might. Its single market had a GDP of €15.9 trillion ($18 trillion) in 2018, the largest in the world. Although the United Kingdom’s exit from the EU will reduce this to some extent (depending on its degree of market alignment), the bloc will still exert significant authority over companies that wish to do business in its territory. The EU has a lucrative market for internet companies: as of March 2019, an estimated 90 per cent of the EU population used the internet, ranging from 98 per cent in Denmark to 67 per cent in Bulgaria.

The EU initially responded to the internet by recognising its social, educational, and cultural importance, while also acknowledging its potential to disseminate harmful and illegal content, and its capacity to facilitate serious crime. The EU’s approach to internet policy evolved to deal with internet service providers that create and run the infrastructure rather than the platforms that emerged in the twenty-first century. In its early years, EU internet policy had two guiding principles developed with the ISPs in mind. One was net neutrality, which required ISPs to treat all online data equally. The other was limited liability, which meant that no ISP could be held liable for hosting illegal content, provided that it removed such content after becoming aware of it. This limited liability provision is contained within the e-Commerce Directive. Articles 13 and 14 of the directive state that, to be shielded from liability, providers that host content must act “expeditiously to remove or to disable access” to information where they have “actual knowledge” of its illegality, and providers that cache content must do so after receiving or an order to that effect.

The rapid growth of US service companies (such as Amazon, Facebook, and Google), their phenomenal market capitalisations, and the lack of any similar European companies that were able to compete with them prompted the EU to rethink its policy. As the value generated by the internet appeared to accrue more and more to US companies, European policymakers began to question limited liability. Platform companies do not just act as neutral hosts of content provided by others, as they use algorithms to track users’ behaviour, and select or adjust content to reflect the needs of these users. In this respect, platform companies resemble editors who are responsible for the content they work on rather than a telephonic services firm, which is not accountable for discussions on its lines. And the opacity of US service companies’ algorithms – which they regard as commercial secrets – has made it difficult for outside observers to judge whether they shape or merely reflect the world that users experience on the internet.

The EU is not a major geopolitical player that can impose itself on superpowers. Nor has it created globally significant service platforms capable of exercising influence across the world. But it has one tool that enables it to shape internet governance – the regulations it applies to its market and the requirements it places on companies that wish to trade in the EU. Due to the size and value of the EU market, multinationals want to trade in Europe. In doing so, they are forced to comply with EU regulations.

Other countries observe the bloc’s approach to internet governance and replicate the aspects of it that appear to be successful. And, finding that they have to introduce new internal procedures to do business in the EU, companies change their behaviour.

The EU is currently focused on the ambitious goal of creating a single digital market. This is set out in the European Commission’s Digital Single Market Strategy, which it estimates could increase EU GDP by €415 billion. The strategy is considerably more interventionist than previous approaches to policy, aiming to establish a harmonised regulatory framework that provides business and consumers with unrestricted access to digital goods and services across the EU. Although its goals are domestic, the strategy has governance implications for any company that wishes to do business inside the bloc.

An example of this is the P2B Regulation, which is designed to promote fairness and transparency for businesses that use online platforms. The regulation comes in response to long-held concerns about the way platforms favour their own services. Although it has not yet been formally adopted, the P2B Regulation reflects a range of concerns about the behaviour of large US platform companies, which it will require to conform to specific standards when operating in the EU market. The European Commission has already fined Google for abuse of its dominant position in the digital-advertising and comparison-shopping markets, as well as for placing restrictions on manufacturers of Android devices. The commission is now conducting investigations into both Amazon and Apple.

Another policy that has attracted global attention is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This came into force on 25 May 2018 with the goal of protecting EU citizens from online privacy and data breaches. It draws on offline data protection principles but addresses the implications of technological advances. It is designed to protect all EU citizens’ data privacy and reshape the way that data controllers in companies across the region approach the issue. Importantly, the GDPR applies to any organisation that holds the personal data of people who reside in the EU, regardless of its location. Under the regulation, the EU can fine organisations up to 4 per cent of their annual global turnover or €20m – whichever is higher – for serious infringements; and up to 2 per cent of annual global turnover or €10m for infringements of their data protection obligations.

Many countries outside the EU are observing the GDPR’s development and considered similar legislation. It has even had an impact in the US, with state legislatures considering provisions to protect privacy that closely resemble aspects of the regulation. The EU’s Digital Single Market Strategy – which will involve further regulatory controls on digital businesses – is likely to have similar global implications.

Some observers have suggested that the world may soon have three internets. These would be a US internet where the rules set by companies provide de facto governance; a Chinese internet that is nationally controlled, serving the interests of the state and facilitating comprehensive digital surveillance; and a European internet in which the EU acts in the public interest to regulate the operations of digital markets and companies.

Given the geopolitical impasse on internet governance, the debate on the issue will almost certainly shift to national and regional initiatives. The US model is widely seen as furthering the self-interest of American companies (an impression reinforced by statements made by both Democrat and Republican administrations) and the Chinese model is mostly appealing to authoritarian governments. As such, the European model is emerging as one that democratic governments – keen to preserve an open market in digital services while protecting the interests of citizens – find increasingly attractive.

Internet governance will not primarily develop in the IGF, or the UN First Committee, or even the ITU (as important as each of these forums are). It is likely to emerge from detailed, bureaucratic, and painfully negotiated efforts to shape the market and incentivise corporate behaviour – an approach backed by the threat of sanctions. These are qualities that, for good or ill, the EU has in abundance and that are lacking elsewhere.

China: Trust, 5G, and the coronavirus factor

The current US-China confrontation is a battle for global supremacy. This contest for influence and leadership is playing out across various economic fields, but most prominently in the technology sector. In the last few years, there has been a lot of talk about the emergence of a new “tech cold war”. Yet the analogy can be misleading: it oversimplifies the dynamics at play – and there is nothing cold about it. The confrontation is hot and fierce, and it is playing out in real time. Washington and Beijing are exchanging blows across various battlefields with varying degrees of intensity. Europe has already been caught in the crossfire on 5G – and things are likely to get worse.

Technology supply and value chains were designed to be efficient and profitable through interdependence and highly specialised global production. European companies are an inherent part of this arrangement: they are deeply embedded in value chains and occupy critical junctures in everything from radio access networks to the lithography optics used in semiconductor production. But tech nationalism is on the rise, and the unravelling of existing structures has already begun. The coronavirus crisis is accelerating this trend. In recovering from a pandemic that has hit the world economy hard, states will reorder their interests and priorities. Europe needs to find a new place in the emerging dynamics.

Washington initially failed in its blunt campaign to push its allies to ban Chinese vendor Huawei and its state-owned competitor, ZTE, from the roll-out of 5G telecommunication networks. European leaders, especially those at the heart of the European Union, were reluctant to move decisively against companies that had been important partners for years and were a key part of their 3G and 4G systems. But US policies ignited a sincere debate across the EU about the future composition of telecoms infrastructure and, as a result, relations with China more broadly.

American officials argued that Chinese vendors posed an unmitigable security risk to Europe’s communications infrastructure and the backbone of the interconnected reality of the 5G world. However, Chinese tech champions – especially Huawei – embodied the strengths of a tech ecosystem that could rival Silicon Valley’s. They often did so by benefiting from massive state subsidies, favourable domestic market conditions in China, intellectual property theft, forced technology transfers, and enormous amounts of state-backed capital for research and development – which boosted indigenous innovation.

Washington has huge incentives to slow the erosion of US tech dominance and the broader power shift towards China – especially in the midst of a pandemic that has shut down much of the US economy. Unemployment in the United States is at a historic high, and the health emergency will likely be followed by a recession. To minimise China’s relative gains, the US administration is willing to maximise economic pressure on Beijing.

In May, the US Department of Commerce presented the latest in a long line of measures designed to achieve this: tightened restrictions on microchip sales to Huawei and its subsidiaries. With the move, the department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) dealt a massive blow to the Chinese tech champion. This was quickly acknowledged by Huawei, which stated that it is now fighting for survival.

The BIS decided that, beyond placing restrictions on direct sales to Huawei, it would also require the company to apply for licences for purchases of semiconductors that are “the direct product of US design and technology”. Semiconductors are both critical to Huawei’s supply chain and one of the few remaining chokepoints for China’s tech ambitions, as the country’s capacity to mass-produce them is limited to just a few companies. Thus, the latest legal manoeuvre especially targets Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which accounts for more than 50 per cent of global sales. The company has moved to the centre of the US-China confrontation, as Huawei needs access to high-performing microchips to fulfil its 5G ambitions. For years, the most compelling argument for Huawei has been that it can provide high-quality goods quickly and at a low cost. It has now become much more difficult for the firm to do so.

The full implications of the BIS decision are still unclear; there may be loopholes in it. But, with this latest salvo against the Chinese tech sector, Washington has emphasised that it takes the issue very seriously. And the current crisis plays into this, given US fears that China will capitalise on its opportunity to end the coronavirus-induced economic lockdown earlier than other countries.

China is an economic competitor that is exiting the first phase of the pandemic earlier than others due to the authoritarian nature of its regime, its high degree of digitalisation, and its existing surveillance structures, which extend to the neighbourhood level. These structures, which predate the digital age, have the capacity to control limited outbreaks more successfully than those in the West. Even during the height of the health emergency, strategically important sectors – including the indigenous microchip industry – continued to operate (even if at slightly limited capacity). And, by now, the tech sector has almost returned to its pre-crisis productivity level.

The Chinese leadership has announced initial stimulus packages to make up for the economic losses created by the lockdown, putting 5G roll-out and the construction of data centres at the heart of these measures. The nationwide introduction of 5G with up to 600,000 base stations – announced in late March – could give Chinese companies a huge competitive advantage over their rivals in their push to digitalise the economy. And more is to come: China is set to spend $1.4 trillion on boosting its tech sector over the next five years.

While it currently intends to approach licence applications under the presumption of denial, the BIS could still issue them to TSMC for limited production. This could be necessary to ensure that the company remains competitive, as sales to China make up almost 20 per cent of its business. Huawei has long expected US-China relations to deteriorate and almost certainly has a significant stockpile of the most critical supplies but, in the fast innovation cycles of the tech sector, these are only useful for a limited amount of time. And it is unclear how long supplies will last, or how quickly Chinese companies will be able to provide indigenous solutions to the problem. Even though the Chinese government places a huge emphasis on such solutions (and is investing a lot of money in them), it will have no real alternatives to non-Chinese products on the necessary scale in the short term.

The latest move by the BIS will make Huawei less international and more Chinese. The company will need to prioritise the enormous domestic 5G market – even at the expense of customers elsewhere. Accordingly, Huawei’s ability to fulfil contracts has become another important consideration for European operators and governments as they decide on the composition of their new network infrastructure. Reliance on Huawei could be a gamble in terms of not only politics and security but also economics.

The European 5G debate

At various times in the last few months, commentators in the media have argued that European telecommunications operators will not exclude Chinese vendors, implying that the US has lost the battle over the issue. But, in reality, the debate is far from over and will be heavily influenced by the coronavirus. In late April, EU member states were supposed to report on the measures they had taken to comply with the EU’s toolbox, a landmark set of policy guidelines for securing 5G networks in their role as critical infrastructure. Virtually all EU member states have complied with this request. But few of them have made a final decision on the role of high-risk vendors.

There is a pending debate on the topic in the Netherlands, where operator KPN has announced that it will swap from Ericsson to Huawei in maintaining its radio access network. Several European countries have introduced national legislation in the area. For example, French restrictions on Huawei’s and ZTE’s equipment in the core of the mobile network predate the 5G debate, while Sweden and Estonia have taken a case-by-case approach to Chinese firms that involves the security services. All of them place significant restrictions on Chinese vendors in their networks, but they also still allow for a degree of strategic ambiguity. Denmark is likely to adopt a restrictive approach soon. Announcements pointing towards the exclusion of Chinese vendors have been made in Romania, the Czech Republic, Italy, and Poland. But the legislative processes to that effect are unfinished – and, for example, in Poland, heavily contested. This has sometimes led to delays in spectrum auctions.

The most technologically and intellectually sophisticated approach to the problem has come from the United Kingdom’s National Cyber Security Centre. In contrast to its continental European counterparts, the organisation has years of experience in analysing Huawei equipment in a very in-depth fashion, and has been alert to the impending security risks for more than a decade (in relation to 3G and 4G). The UK has taken the most decisive step in Europe by banning ZTE outright, and by proposing significant limitations on Huawei’s future role in its 5G infrastructure.

With the pandemic prompting calls to reassess supply chains for critical goods, some British MPs have increased pressure on the government to apply further restrictions on Huawei. This is likely to lead to a controlled phase-out of Huawei technology in the next few years, an example that many European governments may follow. Somewhat counterintuitively, Norway – another country just outside the EU – has received little attention for its main operators’ decision to roll out 5G technology without Chinese equipment.

Germany, above any other EU member state, is key to the outcome of the debate in Europe. This due not only to the size of its telecoms market – which is the largest in Europe – but also to its special relationship with China and the significant presence of Huawei and ZTE equipment in its existing infrastructure. The German debate has been fierce, with the government split on how to respond to the challenge – interestingly, not along party lines of the grand coalition, but between those focused on foreign, security, and cyber issues and those who mainly deal with the economy. Germany’s IT security and telecoms laws were both due to be updated early this year. Yet, so far, only a first draft of the changes to the IT security law has surfaced. The preliminary version includes a clear reference to the EU’s 5G toolbox and calls for non-technical factors, such as trustworthiness, to be relevant in the assessment of a vendor. But it remains unclear in how Germany will assess the trustworthiness of suppliers.

A question of trust

Trust in China has become a huge issue for Europeans. Beijing’s attempts to withhold information about the outbreak of the coronavirus and its initial management of the crisis have received widespread international criticism. Simultaneously, China’s assertive attempts to shape the global narrative on the pandemic through so-called mask diplomacy or outright intimidation demonstrate that its communist leadership – with its back against the wall – has little time to play nice with Europe. China is focused on solving the domestic economic problems that the pandemic has created, including massive job losses, through increased spending at home.

Europeans seem to have been put on the back foot by Beijing’s new approach. Although Europe made a significant course correction in its overall assessment of China in 2019, their relationship is now deteriorating with incredible severity and speed. The pandemic will have a lasting impact on China’s image in the world. And, even more so, it will shift the techno-nationalist Chinese leadership’s attention inwards in ways that make mutually beneficial cooperation increasingly unlikely. China will push to further decouple from international suppliers, prop up its domestic champions, and reduce its dependencies.

For Europe, the timing could not be worse. The post-pandemic economic outlook is bleak. The recovery will be bumpy. As the pandemic lockdown has demonstrated, there are deficiencies in the digitalisation of even Europe’s leading economies. Investment in digital infrastructure, with a special focus the swift introduction of 5G, seems like an especially reasonable way forward. The overall economic situation could make telecoms operators more inclined to choose the cheapest available option. As Chinese vendors already permeate the European market for telecoms infrastructure, they could easily make an economic case for greater reliance on them.

But the countervailing argument may weigh more heavily: the pandemic has made clear that dependence on China for the supply of critical goods (such as masks and personal protective equipment) puts European governments at the mercy of the Chinese Communist Party in times of crisis. The coronavirus has revealed the importance of critical infrastructure to European citizens. And dependence on China has become part of the public debate across Europe, while scepticism about the country’s reliability as a business partner will affect the political climate in most European states for months, if not years, to come. As a recent poll by the Körber Foundation shows, 85 per cent of Germans seek to reshore production capabilities and critical infrastructure to enhance crisis resilience – even if this comes at an economic cost.

It is troubling that, on basic digital infrastructure, most European countries are not up to speed in the truest sense of the word. This could damage Europe’s long-term market position. As 5G will become an enabling technology for a new digital ecosystem in the next five to ten years – as it reaches its full functionality – Europe will need to support its major firms in the market by protecting them from unfair competition and Chinese takeovers. In this regard, EU regulation is advancing and has proven to be a powerful weapon in a battle that no member state can win by itself.

Coronavirus choices

The coronavirus crisis is a turning point for Europe’s approach to technology and geopolitics. By seizing the moment for an economic rethink, the continent should make a renewed push for European solutions to challenges that are indifferent to the borders of the nation state – pandemics and cyber threats being the most prominent, but certainly not the only, examples of this.

Connectivity has been a buzzword in Brussels that never really caught on in the public discourse. Now that citizens have experienced the disastrous consequences of a breakdown in the international connections they rely on, digitalisation could take centre stage in their efforts to recover from the crisis. Europe needs to find a way to not only pay down debt but invest in future competitiveness.

Beijing will move swiftly while the rest of the world grapples with the crisis. And this will not be limited to domestic policy. It is also likely to entail a renewed focus on digital connectivity as part of its Belt and Road Initiative, as well as enhanced efforts to build a digital international order that caters to the interests of the Chinese Communist Party. EU member states need to adjust to this new environment as they make decisions on the economic recovery.

European discussions about technological sovereignty are an important first step in this direction. It is necessary to find pressure points through which to influence the debate on the issue and move from reaction to action. European companies that are part of global value chains are dependent on a rules-based order and commonly defined standards. Before the escalation between the US and China of the last few years, most Europeans had little awareness of the potential limitations they faced in access to technology, research, and innovation. Their commitment to deep integration and networked thinking left little room to consider vulnerabilities among all the opportunities. One could have foreseen the dynamics that have unfolded in recent years, but it seems that Europe needed a rude awakening from its deep geopolitical slumber to understand how the world around it is changing.

There is a persistent myth that Europe does not have what it takes to prevail in the tech world of the twenty-first century and, therefore, can only choose which masters it will serve – be they in Silicon Valley or in Shenzhen. Europe does not currently field a competitor to big US players Amazon, Facebook, and Google or their Chinese equivalents Alibaba, Tencent, or Baidu. But Europe has what it takes to become a force to be reckoned with in the tech space. The continent has 6.1 million developers (compared to 4.3 million in the US) and multiple tech hubs – from the classic top three of London, Berlin, and Paris to the vibrant centres of Stockholm, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Dublin, Helsinki, and Madrid.

Members of the EU have an especially significant long-term advantage in the freedom of movement of humans and capital across their borders with one another, as well as their common regulation and their increasingly appealing investment climate – given the unpredictability of US and Chinese policies and market conditions. The European Commission has set out ambitious targets to ensure that Europe not only has a powerful market but is also a leading innovator in technology. To hit these targets, the Commission will need the full support of all member states and new partnerships with like-minded players, such as Japan, Australia, and South Korea.

As the volatile US-China relationship changes almost daily, Europe urgently needs to build up its resilience against external shocks. Washington and Beijing are considering several extreme measures related to technological decoupling that, aside from their security implications, could throw global supply chains into disarray. These include potential US sanctions on Chinese companies that trade in US dollars, as well as Chinese threats against the status quo in the Taiwan Strait. If the developments of the past two years have demonstrated one thing, it is that such high-risk, low-probability scenarios deserve far more attention than they received in the past.

The view from Spain: The EU’s bid for digital sovereignty

Andrés Ortega Klein

The idea of European digital sovereignty suggests the control by Europeans of their economic environment – in this case the digital environment – even when there is a high level of interdependence. It is always a relative concept.

The coronavirus crisis will impact on its fate in two ways. On the one hand, the pandemic has made it clear that Europe – the European Union and its member states – is overdependent on supplies, both in technology and health, from China and other countries; something that Spain, one of the countries that has suffered greatly from covid-19, has experienced first-hand. The process of deglobalisation and greater nationalism that it has accelerated will lead to a greater effort to control – in some cases to reshore, or even to nationalise or “Europeanise” – parts of supply chains.

On the other hand, the consequent economic crisis will lead to a greater financial focus by EU member states and institutions on reconstruction. And this reconstruction has to lead to more investment in research and development (R&D) in the digital field, even at a time when there will be great pressures on EU and national budgets. If European countries – including Spain, which lags behind in R&D spending – want to compete with the United States and China in this strategic field, they need to increase public and private investment. This has to be part of the industrial and commercial strategy of the EU. The fallout from the crisis will also lead to a rethink of the need for ‘European champions’ and a consequent revamp of EU competition policy. Seen from southern Europe, those champions cannot just be Franco-German. It can begin from a Franco-German initiative, as with GAIA-X or the virtual network for artificial intelligence (AI). But to be truly European, those initiative must include other member states, not just France and Germany.

When the Spanish philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, famously wrote in 1911 that “Spain is the problem and Europe the solution,” he was thinking mainly about science and what we now call technology. “Europe is science above all else,” he said. More than a century later, we could say that Europe should be science and tech above all else. Moreover, Spain’s efforts in this field have a distinctly European ambition, in the sense that Spain, alongside other EU member states, is too small to compete by itself, and, in some ways, even to cooperate, beyond being a client or a user, with the US and China. Even the US is too small in many senses, and should cooperate more with the Europeans in this field.

Spain is an advanced economy which dominates some technology sectors and has some leading research centres. But investment in R&D is inadequate in Spain: it shrunk in the years of the “Great Recession” and only began to recover afterwards. Moreover, it still trails GDP growth. We will see what happens now. Total public and private investment in research, development, and innovation stands at 1.24 per cent of GDP (2018), down from 1.4 per cent of GDP in 2010 but still below the EU average of two per cent. In 2016 and 2017, the private sector increased its R&D investment by 3 per cent. While this is positive, public sector investment fell by a similar amount in 2016, totalling €3.260m. Unlike other countries, Spain, despite having a “State Plan of Scientific and Technical Research and Innovation 2017-2020”, does not have a defined general strategy on what its priority technology sectors should be, in general and with respect to China. As a country, Spain still needs to outline a technology and digitalisation strategy. This has to be part of a wider new industrial policy, especially given the manner in which the coronavirus crisis has shown the importance of digitalisation in keeping the economy going during lockdown, and the fact that countries with a strong industrial sector, like France and Germany, have better weathered such a crisis.

Spanish and other European firms complain that they are in a situation of excessive, even “neocolonial”, dependence, on the big US and Chinese digital companies. The notion of European digital sovereignty would thus constitute a form of liberation for the tech field, even if cooperation with these US and Chinese companies is unavoidable and desirable. Spain now views its European policy in a pragmatic way. In the tech and digital field Spain would benefit from more funding from the EU and stronger industrial alliances with European countries and companies. It hopes that such opportunities will grow with the policies being put in place in the EU through the Next Generation EU recovery fund and the union’s seven-year multiannual financial framework budget for 2021-2027, in which digitalisation and sustainability will be priorities. This could lead to greater Spanish involvement to push for greater European autonomy.

But while pursuing a European approach, Spain sees cooperation with US tech firms as both necessary and unavoidable. It views cooperation with China similarly, albeit it wants to see a greater degree of equilibrium and reciprocity on both the EU-China and Spain-China bilateral fronts. The “EU-China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation” adopted in November 2013 covers cooperation in science and technology. It was renewed in 2017 to emphasise innovation, the cross-border transfer of R&D results, and greater reciprocity in access to research centres; demands the EU had made since 2016.

For Spain, Latin America provides an added dimension to its tech relations with China. We could talk about a “technological triangle”. This dimension, especially the digital one, features at the Ibero-American Summits. China is also very present in the region, with investments and trade, albeit mainly in raw materials, but also interests in the tech field. For this reason, Spain’s approach to Latin America will also have to take into account China and its technological involvement in the region. This can be seen in the example of technological cooperation between Spanish, Chinese, and Latin American companies and research centres. There is thus a technological relationship between Spain and Latin America, another between China and the region, as well as one between China and Spain. This “technological triangle” could prove interesting and benefit each of its three elements.

On 19 February 2020 the European Commission issued three major initiatives, which were generally welcomed by Spain: a statement concerning Europe’s digital future, a white paper on AI, and a “European Data Strategy”. These outlined the major priorities in this field for the commission’s term, and have been supplemented by other post-covid statements, like the European Council’s “Shaping Europe’s Digital Future”. The commission’s announcements led Andrea Renda, of the Centre for European Policy Studies, to welcome the dawn of “Digital Independence Day” in Europe. This is debatable. While the impact of the coronavirus is going to force changes in these strategies, the commission had initially earmarked an annual budget of €20 billion for European AI. Even if it generates a multiplier effect, by way of comparison, Alphabet, Google’s parent company, spends more annually on its R&D. To be effective and credible – to end the notion of “digital neocolonialism” (or “techno-oligopolist dependency”) –European digital sovereignty must be matched by sufficient European resources.