A quick guide to Libya’s main players

In Libya there are very few truly national actors, the vast majority are local players. This guide explains who the players are and what they control.

Introduction

In Libya there are very few truly national actors. The vast majority are local players, some of whom are relevant at the national level while representing the interests of their region, or in most cases, their city. Many important actors, particularly outside of the largest cities, also have tribal allegiances.

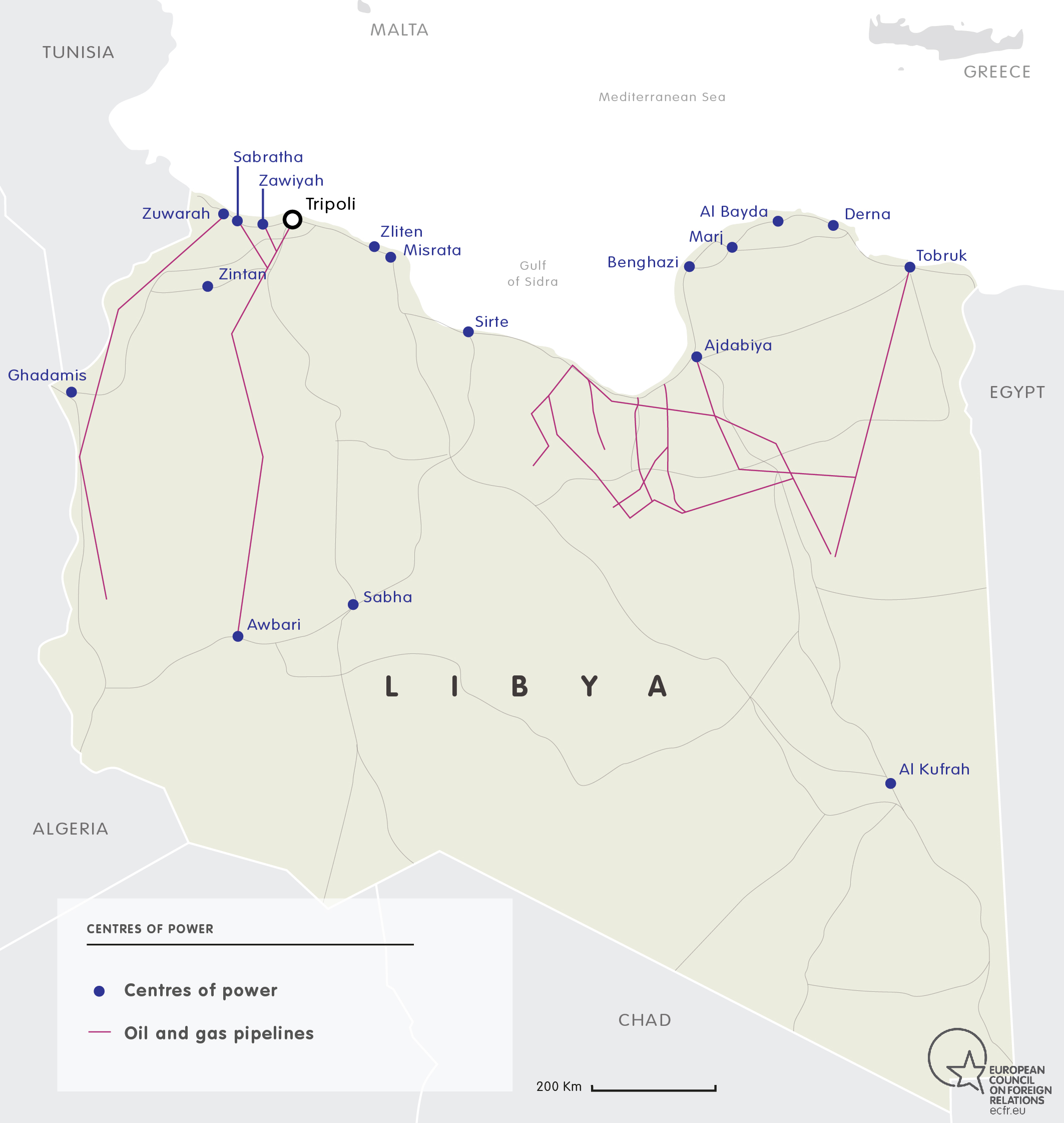

Since the summer of 2014, political power has been split between two rival governments in Tripoli and in Tobruk, with the latter having been recognised by the international community before the creation of the Presidency Council (PC) – the body that acts collectively as head of state and supreme commander of the armed forces – in December 2015. Several types of actor scramble for power in today’s Libya: armed groups; “city-states”, particularly in western and southern Libya; and tribes, which are particularly relevant in eastern and southern Libya.

Political actors

One country, three governments

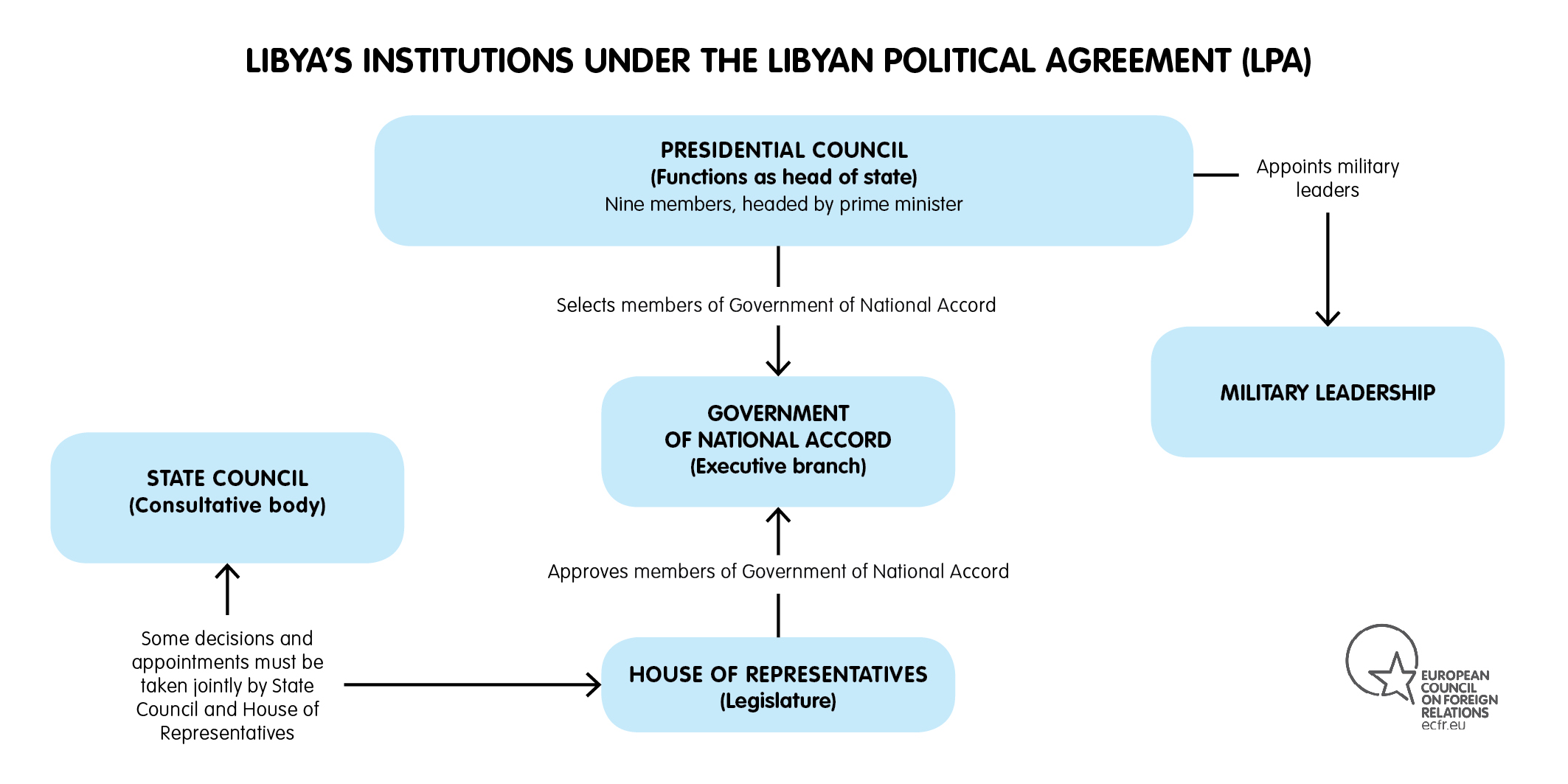

At the moment Libya has three centres of power. The first is the Presidency Council (PC), which has been based in Tripoli since 30 March 2016. The PC is headed by Fayez al-Sarraj – a former member of the Tobruk Parliament, where he represented a Tripoli constituency – and it was born out of the signing of the UN-brokered Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) in December 2015. According to this agreement, the PC presides over the Government of National Accord (GNA), also based in Tripoli. The GNA should be endorsed by the Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HoR) ac-cording to the agreement, but on two occasions the HoR has voted down the list of ministers.

The second centre of power is the rival, but ever weakening Government of National Salvation headed by Prime Minister Khalifa Ghwell – resting on the authority of a rump of the General National Congress (GNC), the resurrected parliament originally elected in 2012. The Government of National Salvation was also based in Tripoli, although it no longer controls any relevant institutions. In October 2016, Ghwell tried to reassert himself but failed to gain wider support and his forces were kicked out from Tripoli in the spring of 2017. The vast majority of the members of the GNC (also known as the “Tripoli Parliament”) have been moved across to the State Council, a consultative body created under the LPA which convenes in Tripoli and is headed by Abdul Rahman Swehli, a Misratan politician (and HoR member) who had previously been threatened with EU individual sanctions.

The third centre of power is made up of the authorities based in Tobruk and Bayda, which were also supposed to work under the LPA. The House of Representatives (HoR) in Tobruk would become the legitimate legislative authority under the LPA but it has so far failed to pass a valid constitutional amendment to enshrine itself as an authoritative institution. Instead the HoR endorsed the rival government of Abdullah al-Thinni which operates from the eastern Libyan city of Bayda. The Tobruk and Bayda authorities have been aligned with the Egypt-aligned, self-described anti-Islamist general Khalifa Haftar, who leads the Libyan National Army (LNA).

In Libya there are very few truly national actors. The vast majority are local players, some of whom are relevant at the national level while representing the interests of their region, or in most cases, their city. Many important actors, particularly outside of the largest cities, also have tribal allegiances.

Since the summer of 2014, political power has been split between two rival governments in Tripoli and in Tobruk, with the latter having been recognised by the international community before the creation of the Presidency Council (PC) – the body that acts collectively as head of state and supreme commander of the armed forces – in December 2015. Several types of actor scramble for power in today’s Libya: armed groups; “city-states”, particularly in western and southern Libya; and tribes, which are particularly relevant in eastern and southern Libya.

Prime Minister al-Sarraj and the Government of National Accord

Initially, the PC comprised nine members. Two of them started boycotting its meetings early on, while others became inactive over time so that now only two figures re-main active on a daily basis within the council: PC President Sarraj and his deputy, Ahmed Maiteeq.

Prime Minister al-Sarraj is not a strong figure on his own, but some of the other eight members that originally madke up his PC have close links to powerful stakeholders.

His deputy, Ahmed Maiteeq, who served a short stint as prime minister of Libya before being hit by a court ruling, comes from the powerful city-state of Misrata, which is the biggest backer of the GNA from both a political and military standpoint, though some elements in the city remain opposed to it. Misrata’s militias were a crucial component in the downfall of Gaddafi and are still one of the two most relevant military forces in the country, having taken the lead in the fight against the Islamic State group (ISIS) in Sirte in 2016.

Another important deputy is Ali Faraj al-Qatrani, who is aligned with General Haftar, who in turn heads the LNA – the other large military force. Al-Qatrani has boycotted meetings of the PC almost from start on the grounds that it is not inclusive enough, and has publicly called for military rule under the LNA.

Another member of the Presidency Council, Omar Ahmed al-Aswad, who comes from the town-state of Zintan in western Libya, has also previously boycotted the meetings of the PC. Zintan played an important role in the fall of Gaddafi-controlled Tripoli in 2011 and the head of its military council, Osama Jweili, was appointed commander of the GNA’s western region military zone in June 2017.

Others include Abdessalam Kajman, who aligned with the Justice and Construction Party of which the Muslim Brotherhood is the largest component while another deputy Musa al-Kuni was selected to represent southern Libya but later resigned.

Finally, Mohammed Ammari represents the pro-GNA faction within the GNC and Fathi al-Majburi, who was once an ally of the Facilities Guards (PFG) commander Ibrahim Jadhran until he was dislodged from key eastern oil ports by the LNA.

Two other institutions are based in Tripoli and play a major role in Libya’s politics. The Central Bank of Libya, which is where oil money is paid and government money is disbursed. Though pledging loyalty to the PC, it has had an uneasy relationship with it. The National Oil Corporation (NOC) is also formally loyal to the PC but has had relatively good working relations with Haftar’s LNA after its seizure of eastern oil ports.

Abusahmain, Ghwell and the “Tripoli government”

The speaker of the General National Congress Nouri Abusahmain and the prime minister of the “Government of National Salvation”, Khalifa Ghwell, come from the cities of Zwara and Misrata respectively. Their military support base is the Steadfastness Front (Jabhat al-Samud) of Salah Badi. Initially they represented the Libya Dawn coalition which included Islamists, the city-state of Misrata, and several other western cities (including parts of the Amazigh minority). Both Ghwell and Abusah-main have been hostile to the PC and have been subjected to sanctions by the EU because of this. Their support base has shrunk considerably and, at the moment, it is unclear whether they are capable of re-establishing a presence in Tripoli.

Haftar, Aguila Saleh, and the Tobruk power centre

The relationship between Haftar and the Speaker of the Tobruk parliament, Aguila Saleh Issa, has ebbed and flowed since 2015. Over the past year, it has become in-creasingly strained. Haftar oversees his forces from his headquarters in Marj (in eastern Libya) and has exerted pressure on both the Bayda government and the HoR in Tobruk. In July 2017, Haftar declared that his forces had “liberated” Benghazi from both the Islamist-dominated Benghazi Revolutionary Shura Council and ISIS, but fighting continues in pockets of the city. Haftar’s camp has faced several challenges from within and without, not least from erstwhile ally Faraj Ghaim, who was appointed deputy interior minister of the Government of National Accord in 2017.

The Tobruk centre of power has also established its own Central Bank and its own NOC which are not recognised on international markets and which were supposed to merge with their Tripoli counterparts. The merger has, so far, not happened.

The Former Regime

Developments over the past year have made elements associated with the former Gaddafi regime more confident than at any point since his ousting in 2011. Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, the son of the former Libyan dictator, was reported “freed” in June 2017 after being held for six years by a militia in Zintan. Speculation that he seeks to make a comeback – though in what way is not clear – continues amid growing consensus that former regime elements should be included in any sustainable political settlement. The former regime camp is far from united or cohesive, however, and includes prominent figures like Saif al-Islam, tribal elements, and armed groups including the one that sabotaged the Great Man Made River Project in late 2017, disrupting the water supply in Tripoli and its environs.

The Islamic State group in Libya

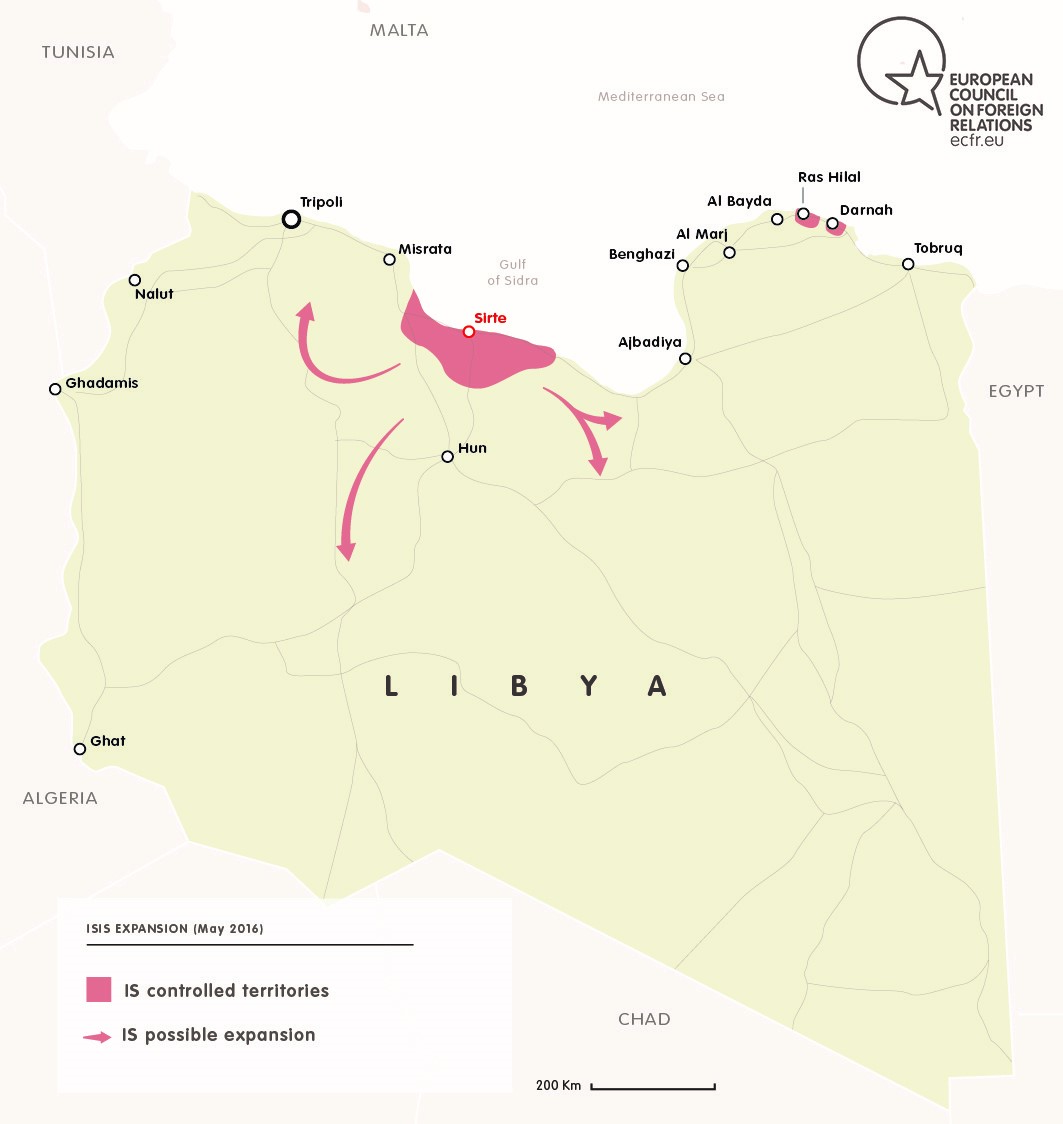

Also called Tandhim ad-Dawla (the Organisation of the State) by Libyans, ISIS controlled the central Mediterranean coast of Libya around the city of Sirte until a Misratan-led operation to uproot it began in May. ISIS has carried out attacks in all major Libyan cities, including the capital Tripoli. ISIS has also had a presence in other parts of Libya, including Benghazi, where it was largely defeated by Heftar’s LNA. Its affiliates have mostly been driven out from the towns of Derna and Sabratha by anti-Haftar forces.

Regional actors

Egypt

No other Arab country plays as powerful a role in Libya as Egypt. Testament to Egypt’s involvement in the region is the regular travel Libyan leaders make to Cairo. The relationship between Tobruk and Egypt is not just defined by significant arms deliveries but also by a shared political project: eradicating political Islam and enhancing the autonomy of eastern Libya. For Egypt, according to some authors, having Cyrenaica – the eastern region of Libya – under the role of a leader that is friendly to Egypt (Haftar for instance) would create a buffer zone with ISIS and a territorial hinterland for any opposition to the regime in Cairo.

Nevertheless, over time Egypt has put out at least two statements that contradict this position. On the one hand, diplomats and the MFA have given assurances of their support to the UN-led political process; on the other, the security apparatus has supported Haftar, even when it was clear that he was on a collision course with UN-backed unity efforts.

United Arab Emirates

Although sharing some of the same goals as Egypt, the UAE has a more nuanced position on the situation in Libya. Reportedly, it has been more supportive of UN negotiations and ultimately less engaged on Libya since its intervention in Yemen. Nevertheless, Emirati weapons are still delivered to both Haftar and the militias of the city-state of Zintan, according to a report from a UN panel of experts. Moreover, the UAE’s political influence should not be underestimated. Aref al-Nayed, who was Libyan ambassador to Abu Dhabi until he resigned in October, was key to the UAE’s role in Libya and was even touted as potential prime minister at one point.

Turkey and Qatar

Neither Turkey nor Qatar have the same level influence on the Government of National Salvation and its allies that Egypt and the UAE have on the Tobruk side. Turkish companies have, according to the UN panel of experts, delivered weapons to one side (the defunct Libya Dawn coalition) and Qatar has maintained links with one Libyan politician and former jihadist – Abdelhakim Belhadj – since 2011. Yet none of the major Libyan actors respond to input from Ankara or Doha the way that Tobruk aligns itself with Cairo’s policies.

Algeria and Tunisia

The two Maghrebian countries, while having a high level of interest in what happens in Libya, have not built a network of proxies in the country like other Arab or regional powers. Both countries have been vocal supporters of reconciliation and a political solution while closely coordinating with each other to contain the spillover from ISIS’ presence in Libya.

Jihadists

Libya is home to a range of jihadist groups, from the Islamic State group (ISIS) to al Qaeda-linked groups, to other Salafi-jihadi factions. Some are wholly indigenous and rooted in particular locales while others – particularly ISIS affiliates – include many foreigners at both leadership and rank and file level.

The legacy of LIFG

Libya’s jihadist network can be divided along generational lines, starting with those who emerged in the 1980s. Many from that older generation fought against Soviet-backed forces in Afghanistan. These veterans later created a number of groups in opposition to Muammar Gaddafi, the largest of which was the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) which is now defunct. Several former LIFG figures, including its final leader, Abdelhakim Belhadj, played key roles in the 2011 uprising and went on to participate in the country’s democratic transition, forming political parties, running in elections, and serving as deputy ministers in government as in the case of Khaled Sherif at the Ministry of Defence. This did not sit well with the second and third generation of jihadists – among the former were those who fought in Iraq after 2003, among the latter were those who fought in Syria after 2011 – who lean towards more radical ideologies and reject democracy as un-Islamic. The Libyans that have joined ISIS tend to come from the second and third generations.

ISIS in Libya

Local returnees from Syria helped form Libya’s first ISIS affiliate in the eastern town of Derna in 2014. Many had fought as part of ISIS’s al-Battar unit in northern Syria before returning home to replicate the model with help from senior non-Libyan ISIS figures. The leadership of ISIS in Libya has always been dominated by foreigners. Its leader earlier this year was Abd al-Qadir al-Najdi, whose name suggests Saudi origins. He replaced an Iraqi whom the US claims it killed in an airstrike in eastern Libya in 2015.

ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi recognised the presence of ISIS in Libya in late 2014, declaring three wilayats or provinces: Barqa (eastern Libya), with Derna as its headquarters; Tarablus (Tripoli), with Sirte as its headquarters; and Fezzan (southwestern Libya).

ISIS was driven from its first headquarters in Derna in 2015 by a coalition of forces which included the Derna Mujahideen Shura Council, an umbrella group comprising fighters led by local jihadists including LIFG veterans, who joined with army personnel who had rejected Khalifa Haftar and his Operation Dignity campaign. The same alliance later routed ISIS from its remaining redoubts on the outskirts of the town.

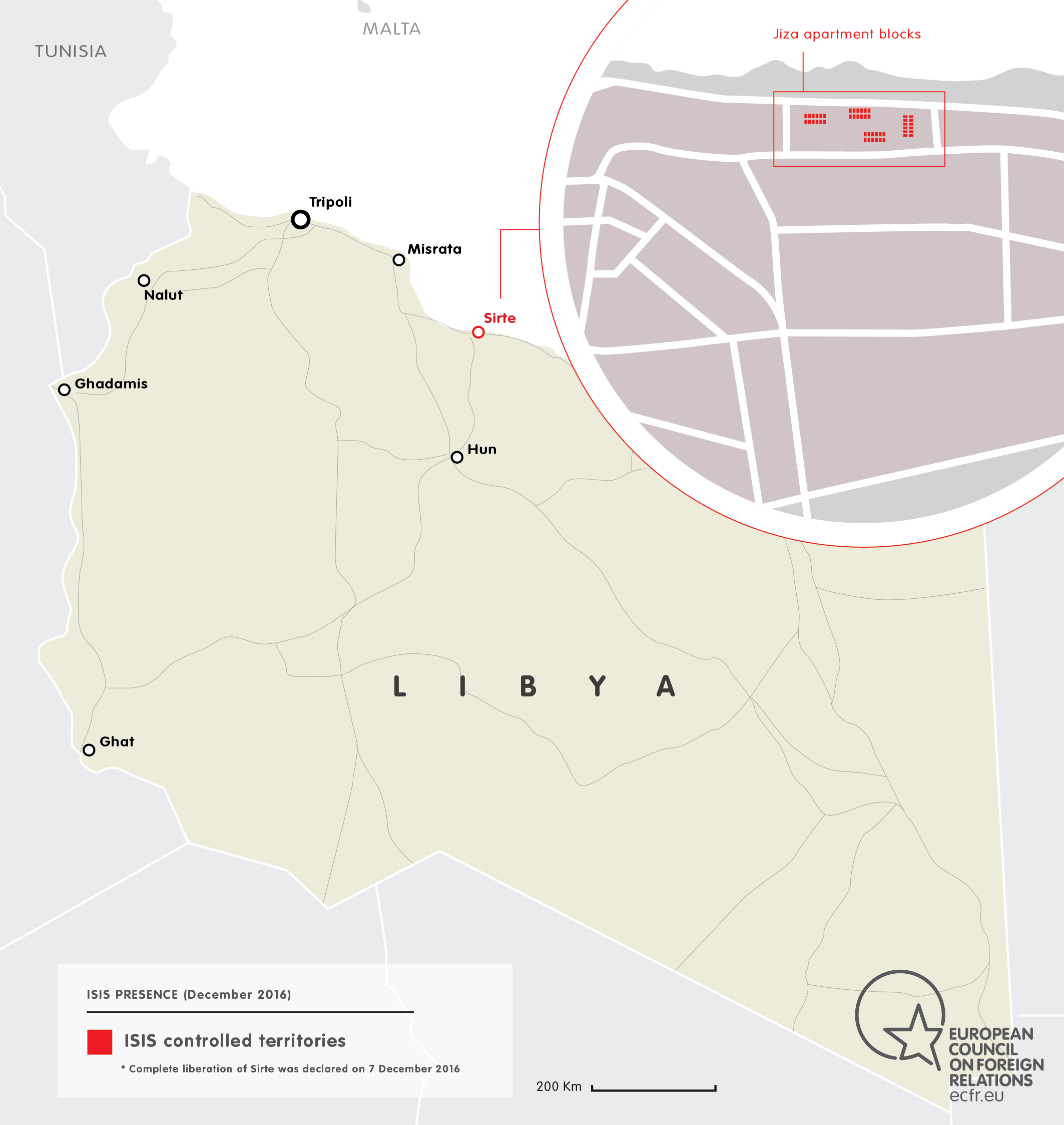

In early 2015, ISIS began to build its presence in Sirte, which was Gaddafi’s former hometown and one of the regime’s last hold-outs. Prominent ISIS cleric Turki al-Binali and other senior figures visited Sirte as the group began to consolidate control. It did so by reaching out to locals who felt aggrieved over the city’s marginalisation in post-Gaddafi Libya. However, the group met some resistance as a number of residents attempted an uprising, which was then brutally quashed. ISIS tried to impose a system of governance on the city, using public executions to instill fear. Sirte became ISIS’ stronghold in Libya until May 2016 when a coalition of Misrata-dominated forces known as Bunyan al-Marsous (BAM) declared war on the affiliate there. The BAM operation, which was accompanied by over 400 US air strikes on ISIS targets in and around Sirte, declared victory in early December.

ISIS also had a smaller presence on the outskirts of Sabratha, a coastal town in western Libya, until a combination of US airstrikes and attacks by local forces – including former jihadists from that first generation – managed to uproot the militants earlier this year. In Benghazi, those fighting Haftar’s Operation Dignity include Libyan and foreign members of ISIS. Although Sirte was the group’s ostensible base, ISIS sleeper cells operate in Tripoli and other cities and towns in Libya. While the Pentagon estimated there were over 6,000 ISIS fighters in Libya prior to the BAM operation, the UN and many Libyans believed that the actual number was much lower.

Many of these fighters fled Sirte before BAM forces entered the city. They then travelled in three directions: south-west towards Sebha, west towards Sabratha and south-east towards the border with Sudan. Most foreign intelligence estimates hold that the group now has upwards of 600 fighters, mostly scattered across Libya’s south-west and central regions, with notable concentrations around Bani Walid and the area south of Sirte, including the Jufra hinterland.

US air strikes on ISIS targets in late 2017 followed increased activity by the group in Libya since the middle of the summer. In August its Amaq news agency claimed that 21 LNA members had been killed or injured in a raid on an LNA checkpoint in the Jufra region. In October ISIS claimed responsibility for a suicide attack on the court house in Misrata, killing at least three.

Ansar al-Sharia and other al-Qaeda affiliates in Libya

Formed in 2012 by former revolutionary fighters calling for the immediate imposition of sharia law, Ansar al-Sharia’s first branch was set up in Benghazi, but affiliates also emerged in towns such as Derna, Sirte and Ajdabiya. After being driven from these cities and towns or weakened by defections to other al-Qaeda-linked groups or ISIS, Ansar al-Sharia announced its dissolution in May 2017.

The UN put Ansar al-Sharia on its al-Qaeda sanctions list in 2014, describing it as a group associated with Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and Al-Mourabitoun. Both groups mentioned also have a presence in Libya, both in the south and cen-tral/eastern regions, largely through Libyans who once worked with them elsewhere, particularly in Algeria, before returning home after Gaddafi was ousted.

Ansar al-Sharia ran training camps for foreign fighters, including a significant number of Tunisians, travelling to Syria, Iraq and Mali. Individuals associated with Ansar al-Sharia participated in the September 2012 attacks on the US diplomatic mission in Benghazi.

While they were, at the core, an armed group, Ansar al-Sharia adopted a strategy between 2012 and 2014 that focused on preaching and charitable work to build popular support and drive recruitment. As a result, it became the largest jihadist organisation in Libya, with its main branch being stationed in Benghazi.

In response to Haftar’s Operation Dignity, Ansar al-Sharia’s Benghazi unit merged with other militias to form the Benghazi Revolutionary Shura Council (BRSC) in summer 2014.

As ISIS tried to co-opt existing networks when attempting to expand in Libya from early 2015, tensions grew between it and Ansar al-Sharia (and by extension with the latter’s associates in AQIM and Al-Mourabitoun) as they competed for members and territory. The rivalry between what remains of ISIS in Libya and al-Qaeda-associated groups is likely to define Libya’s jihadist milieu for some time.

Published in October 2016.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.