Who will the new European Commission serve?

A breakdown of the recent votes by the European Parliament to approve the incoming European Commission, headed by former prime minister of Luxembourg Jean-Claude Juncker.

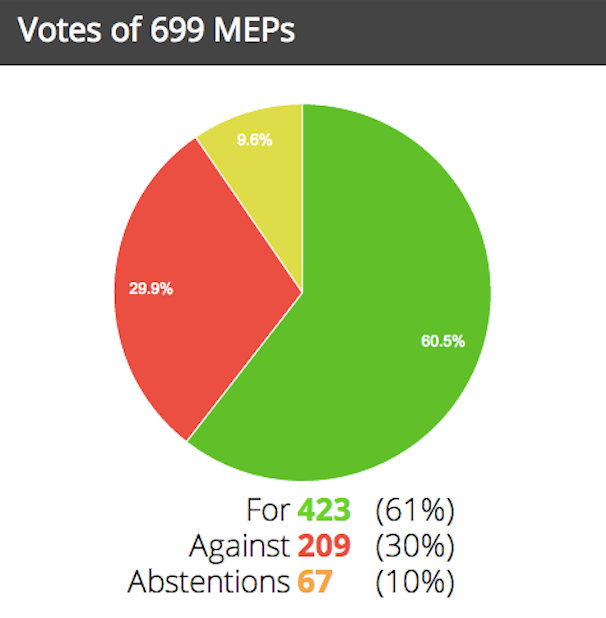

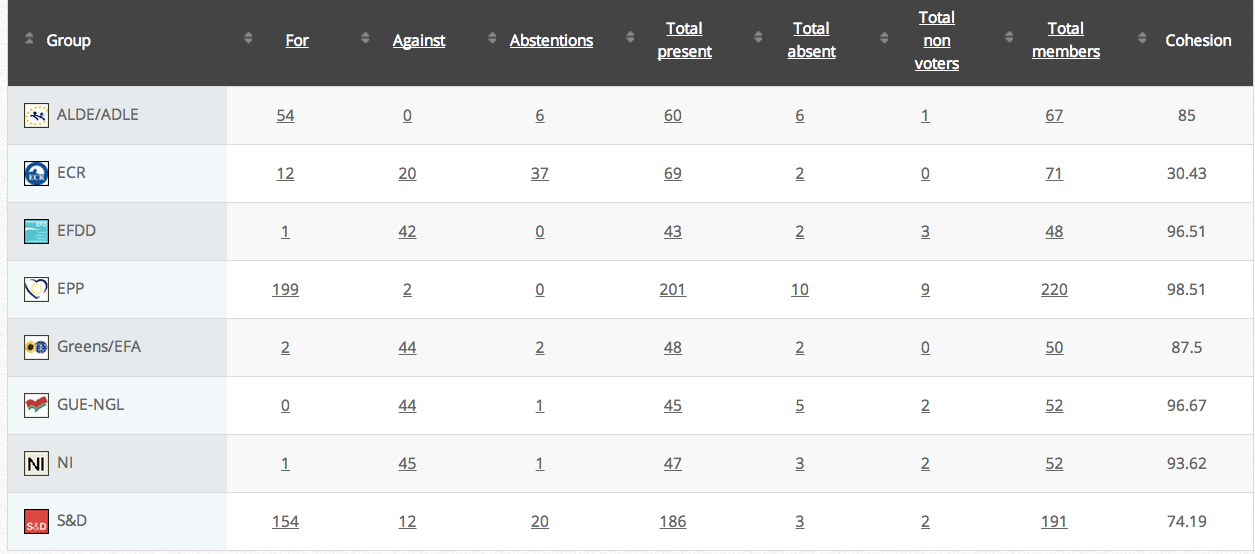

The Juncker Commission will inaugurate on 1 November after having received 423 votes in the European Parliament—a wide majority exceeding the necessary 317 votes to take office by 106 votes. 209 MEPs voted against the Commission and 67 abstained. Looking in some detail at those who voted in favour of the Commission, we see that Juncker obtained 90 percent of the Popular Party vote (199 of 220); 80 percent of the Liberal vote (54 of 67); and 81 percent of the Socialists’ vote (154 of 191). “[1]

Despite this ample majority, Juncker’s Commission has had a more controversial birth than that of its predecessor. With 60 percent of the votes cast, this Commission is well below that of Barroso, who received 70 percent of the votes in his first mandate (2004-2009) and 66 percent in his second. This loss in support reflects the fact that politics in the EU have become less consensual, partly due to the rise of the Eurosceptic parties but also due to divisions within mainstream European parties, such as the Socialists. Due to their internal divisions, the Socialists are perceived as the junior partner in the Commission, but are in fact the pivotal actor that enabled Juncker to become President.

Juncker needed 317 votes to pass, but the Popular (EPP) and Liberal (ALDE) groups only managed to contribute 253 votes (80 percent of the amount necessary for the majority). Falling short of an absolute majority by 56, it is clear that the Juncker Commission owes its position to the Socialists (S&D), who gave it the remaining 20 percent of the votes needed. The final result makes the European Commission a tri-colour government with the following composition of political support: 47 percent Popular (199 votes of 423), 36 percent Socialist (154 of 423) and 12 percent Liberal (54 of 423).

The big question is whose Commission it will become, especially with regards to the balance between austerity and structural reforms on the one hand, and investment policies, employment, and growth on the other. Likely because of this uncertainty, the Socialists’ votes revealed a three-way split. While 154 voted in favour of the Juncker Commission, the 13 Spanish Socialists abstained along with 7 others Socialist MEPs (Germans, Italians, and Poles). Twelve Socialist MEPs voted against (Swedish, some French, and Irish). The British Labour party finally voted in favour, along with some British Conservatives. Thus, Juncker succeeded in dividing the Socialist coalition (British Labour, Spanish Socialists, and Swedes) who in June had voted against him.

Supporters for the Commission are thus a broad mix. What about the no-votes? At the left end of the political spectrum, the European United Left (GUE/NGL) and the Greens (Greens/EFA) have shown almost perfect unity: only one deputy of the left bloc abstained, with the other 44 voting against, and 44 of the 48 Greens also voted against the Commission, which gives them a cohesion in voting of 97 percent and 91 percent respectively.

A further 45 of the total 209 no-votes came from MEPs from the extreme right Europhobic parties who failed to join a parliamentary group (Marine Le Pen’s National Front, the Austrian Freedom Party, Hungarian Jobbik, the Greek neo-Nazi Golden Dawn, Belgian Vlaams Belang, the Italian Northern League, and the Polish Congress party). The rest of the votes against the Commission came from the 42 Europhobes who have succeeded in gaining their own parliamentary group (the Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy party, EFDD), which includes the British UKIP, the “Grillini” Italians, and 20 classic Eurosceptics aligned in the ECR (mainly British Conservatives, Poles, Czechs, and the new German Eurosceptics of Alternative for Germany).

Juncker’s Commission is thus a centrist Commission whose support weakens as you move to the extremes of the political spectrum in either direction. The Commission represents the shrinking pro-Europe political centre in Europe. As such, it faces challenges from right and left.

[1] The sum of all yes-votes is 96% because Juncker earned 16 votes from other political forces. See the table detailing voting cohesion per group for details. [Source: Votewatch Europe]

This article was translated from Spanish by Carla Hobbs, a Research Assistant at the ECFR Madrid office. The Spanish version of this article was originally published in El Pais on 24 October 2014.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.