The Yemen conflict: Southern separatism in action

The Southern Transitional Council’s declaration of “self-rule” threatens to revive the internecine feuds of previous generations.

On 25 April, the Southern Transitional Council (STC) declared “self-rule” over the former territory of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. The move threatens to create further instability in southern Yemen, by heightening the risk of conflict in the area and making it significantly more difficult to address an already dire humanitarian situation – one that could worsen as a result of covid-19.

According to the declaration, the STC formally ended cooperation with President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s internationally recognised government in response to months of non-payment of salaries, as well as a lack of military support, efforts to fuel internal conflict and support terrorism, and a deterioration of public services, particularly those in Aden. The STC attributes all these problems to the actions of the government. And it blames the government for failing to implement the Riyadh Agreement – which they signed last November in a bid to solve long-standing disagreements between them that, three months earlier, deteriorated into military conflict.

For the moment, the political shift has not reignited the conflict, but there is a high risk of military clashes in and around Aden

As part of this agreement, in exchange for the redeployment of military forces, the STC was supposed to gain greater involvement in the UN negotiating process, as well as several official positions in central and local government. Yet, six months after the sides signed the deal, none of its main clauses has been implemented, and military tension between them has increased. The lack of progress in forming a new, slimmed-down government is of less consequence than the military aspects of the deal. Forces on both sides were to be redeployed under Saudi supervision, with a few government troops returning to guard the presidential compound, and most STC fighters leaving Aden. No such redeployment has taken place.

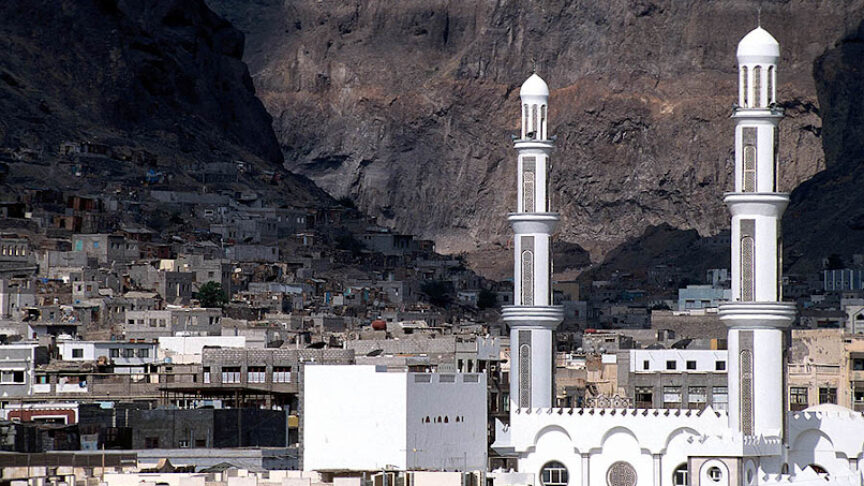

Aden is now the focus of the conflict, thanks to its symbolic importance as the temporary capital, as well as its large population, port, and economic infrastructure. For the moment, the political shift has not reignited the conflict, but there is a high risk of military clashes in and around Aden. Significantly, many southern leaders have disassociated themselves from the declaration.

The STC justified the move by explaining that “four governorates – Marib, Al Mahra, Shabwa, and Soqotra – were already largely self-administered”, and that “the STC sought to add Abyan, Aden, Lahj and Al-Dhale to the same model”. Interestingly, the organisation makes no mention of Hadhramaut, the most important of the governorates politically, demographically, and economically. This suggests that the STC hopes to persuade Hadhramaut’s leaders to follow it. Subsequent fighting in Soqotra between pro-government and pro-STC forces proved inconclusive before, yet again, Saudi mediation led to a ceasefire.

The STC is one of many separatist groups in southern Yemen. Since its creation in 2017, it has achieved prominence thanks to the financial and diplomatic support it receives from the United Arab Emirates. Its international offices lend it a wide public presence. Locally, the UAE recruited, trained, deployed, and financed its military forces. However, since withdrawing from the country last year and handing responsibility for its activities to Saudi Arabia, the UAE has reduced its support for the STC. While the president of the STC made the self-rule announcement from Abu Dhabi, Minister of State Anwar Gargash has issued the only official Emirati response to it to date: he did not explicitly condemn the STC, but said that the Riyadh Agreement should be implemented and that no party should take unilateral action.

Predictably, the declaration was condemned internationally, including by the UN Security Council, the UN special envoy to Yemen, the European Union, Russia, China, Arab states, and even US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. All of them focused on the fact that the move would likely erode Yemen’s capacity to deal with covid-19, while complicating efforts to revive negotiations between the government and the Houthis. And they emphasised the importance of implementing the Riyadh Agreement. While international agencies may treat the STC as the de facto authority for dealing with humanitarian issues in southern Yemen, this is far from constituting political recognition. The UN special envoy and Saudi Arabia hoped to use the covid-19 emergency to make progress in peace negotiations with the Houthis. Now, to their frustration, they have been diverted by this additional problem.

The declaration and its timing raise questions about STC leaders’ vision. They appear to have partially heard widespread advice against making a declaration of independence, as “self-rule” is not quite “independence”, thereby allowing for some wriggle room. The STC also says that it is willing to return to the Riyadh Agreement if the government fulfils its conditions. But the organisation’s leadership could have predicted the negative reaction in Yemen beyond its core support – as it could the international response.

The STC will now face a challenge in not only asserting its legitimacy following the move but also financing its rule (particularly salaries in the security sector), given that its main sources of funds are the post-withdrawal UAE and a Saudi Arabia likely angered by the declaration. It is also increasingly clear that Saudi Arabia also wants to withdraw from Yemen, resulting in a unilateral – albeit ineffective – ceasefire over recent weeks. As a result, Riyadh could well respond to the STC declaration by further distancing itself from Yemen.

The international community insists that Yemen’s future must be addressed within the framework of the internationally recognised state. Like all Yemenis, the people of Aden want peace, security, medical services, a livelihood, and physical and social infrastructure. The STC has struggled to provide any of these things. Instead, the organisation has risked reviving the internecine feuds of previous generations.

While it may hope to use the declaration to achieve a status comparable to that of the Houthis in Sana’a, the STC has far fewer assets with which to do so. The main question for its leadership concerns how to step back without losing face or local support. If it fails to achieve this, far from re-establishing the southern state along pre-1990 borders, the STC could lead southern Yemen into deeper political fragmentation and further conflict.

Helen Lackner is a visiting fellow at the European Council for Foreign Relations and research associate at SOAS University of London.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.