The proof of the European Council pudding will be in the eating

EU leaders need to show that they are not only capable of reaching an agreement between themselves, but also of shaping the post-coronavirus world.

Against the expectations of many (this author included), in the early hours of 22 July, EU leaders reached a deal on the European Union’s budget for the next seven years and on a recovery fund. In addition to the euphoria that they expressed at reaching an agreement – any agreement – given the high-profile divisions between member states, they also focused on the major steps forward they had made in the substance of the accord. The European Commission has been empowered to borrow on the market to make grants and loans to member states through the recovery fund, to avoid adding to their national debt burden. Though it is a technical step, this binds states together and reinforces the idea of the EU as a single entity within the economic recovery.

Perhaps just as groundbreaking was the manner in which EU leaders made the deal, as it seemed to show that EU cooperation was up and running again. After strong, substantive input from Commission President Ursula von der Leyen at the outset of the negotiations – and in close liaison with European Council President Charles Michel – French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel reportedly worked together very closely to sustain pressure for an agreement throughout the 90-hour talks. This was despite their differing ideas about the ideal outcome of the discussions – with Merkel highly sceptical of the proposed scale of the borrowing, and Macron firmly convinced that there was no other option. To misquote Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, this was perhaps the Franco-German couple at its best: acknowledging their differences, but looking forward in the same direction. They knew that, to secure the EU’s future, they needed to find the right balance between the different parties around the table.

And to do so, everybody had to compromise – the “frugal states” (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, and in the end Finland) on the governance structure of the recovery fund and the principle and scale of borrowing to fund grants; and the southern states on the balance between loans and grants. Those who hoped that budget rebates might be abolished after Brexit (such as Macron) had to swallow an increase in the rebate to the frugal states. Even Budapest, which got off lightly on the rule of law conditionality attached to the funds, knew that the German presidency of the Council of the EU would eventually move forward with the Article 7 procedure against Hungary. Still, judging by the initial reactions of leaders across the EU, it appears that no one has compromised so much that they will disown the deal. They all appear to feel a certain sense of ownership of the agreement, having shaped one aspect of it or another.

But has this deal changed the EU for good and created “next generation Europe”, as von der Leyen claims? The proof of the pudding will be in the eating.

Firstly, the budget and the recovery fund have to prove themselves. They need to show that they can get post-lockdown Europe back on its feet economically. The next few months will be crucial in this.

Secondly, leaders must go home and sell the deal to voters. They must do so not by blaming Brussels – as they have in crises gone by – but by explaining why this deal, though a compromise, is in the best interests of their country, as part of the EU. This will not be straightforward for everyone, given that one of the major hurdles in the negotiations was that heads of state faithfully represented the views of the public in each of their countries.

Firstly, the budget and the recovery fund have to prove themselves. They need to show that they can get post-lockdown Europe back on its feet economically.

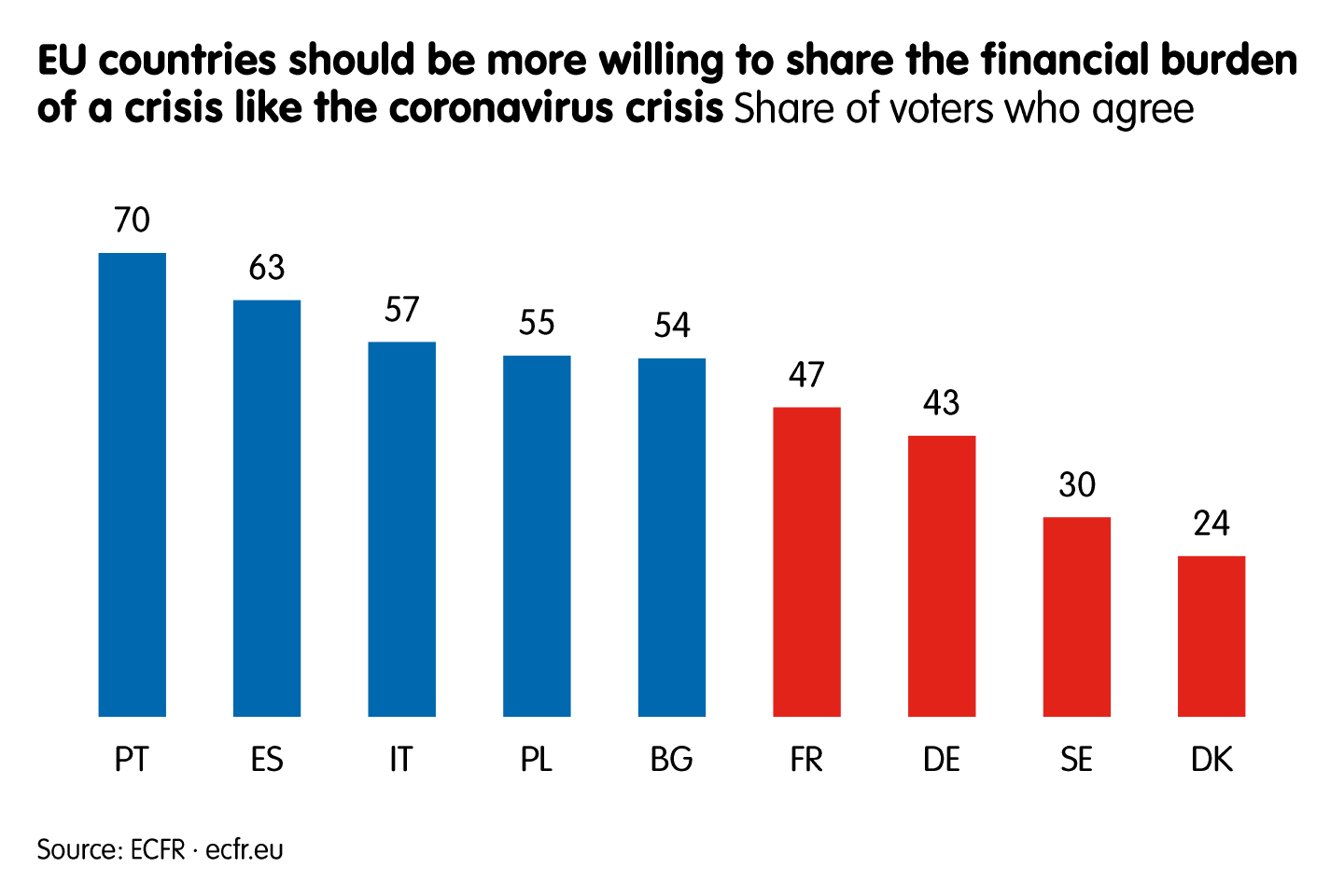

ECFR’s survey data from the peak of the coronavirus crisis show that German, Swedish, Danish, and French voters are not particularly open to the idea of sharing the financial burden of the recovery within the EU. This is in no small part because – like all member states in the survey – they feel that, ultimately, their country had to fend for itself in the crisis. But unlike southern member states – which also feel alone – the frugal four and Germany say that their national government handled the situation reasonably well. These states are still broadly in favour of more European cooperation after the crisis (as are 63 per cent of EU voters overall), but they do not feel such an urgent national need for this as the southern states do: around 50 per cent of Swedish and Danish voters hold this view, compared to 91 per cent of Portuguese, 80 per cent of Spaniards, and 77 per cent of Italians. The rebates for the frugal states will be an important part of the narrative on why this deal works for them too.

More broadly, Europe needs to ensure that the new agreement will be part of a bigger package. EU leaders should show that they are capable of not only reaching an agreement between themselves, but also of shaping the post-coronavirus world.

One of the biggest threats Europeans now face is the climate challenge. Support for a greater effort to tackle climate change has grown everywhere during the coronavirus crisis: according to ECFR’s survey, it is as high as 61 per cent of respondents in the United Kingdom and 60 per cent in Spain – with those who have grown more supportive outstripping those who have become less so in every country covered.

In her post-summit press conference, Von der Leyen promised that “Europe’s recovery will be green”. This must be reflected in how the budget and the recovery fund money is spent – supporting large-scale initiatives such as the creation of 70 million homes with solar panels, and a moratorium on new funding for fossil or nuclear fuels. The EU should invest in pan-European green transport systems, including high-speed train networks that link European cities. And the bloc should devise a European strategy for installing many more network charging points for electric cars, as well as for an alliance between European cities to procure emission-free buses.

And, as part of European global leadership, investment within Europe should go hand in hand with a smarter multilateral approach to the climate challenge – one that recalibrates the EU’s approach to China. If China continues to have little ambition to reduce its carbon emissions, Europe must look for new partners who can help change this – such as India and other developing countries.

So, in sum, while EU leaders may have done much at this summit, they still have much to do to build an EU that will take voters forward with it. But, after marathon negotiations, they probably deserve a short break over the summer before returning to the task.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.