The “more Europe” core four

New ECFR research reveals the Franco-German tandem has a pair of outriders supporting it. But Europe-wide drive for deeper integration is lacking

This is a time of numerous appeals to European unity and strength, be it on migration or trade, on security or a rules-based order. Europeans may be gearing up for closer cooperation in reaction to an international environment that is profoundly less conducive to European interests and preferences. But how strong is the commitment to “more Europe” and deeper integration called for by Angela Merkel in response to the migration challenge and by Emmanuel Macron, concerned at economic disparities and security risks? Which countries appear to be strongly committed and which do not?

Results of ECFR's recently-concluded EU28 Survey 2018 hold the answers to such questions. As part of the study, ECFR asked practitioners and experts from governments and think-tanks all around the European Union to name the member states that they believe are most committed to deeper integration.

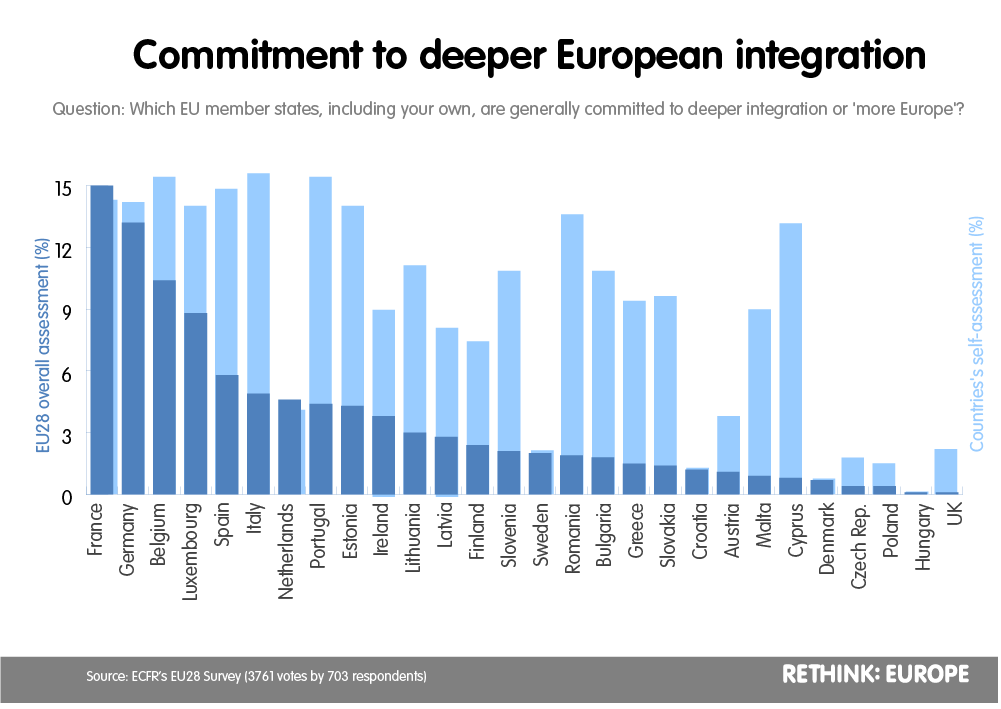

For those who believe in European integration, the results are disheartening: across the EU, respondents consider only four member states to be clearly committed to more Europe: France, Germany, Belgium, and Luxembourg suck up nearly half of the total vote (47 percent altogether, with 15 percent, 13 percent, 10 percent, and 9 percent respectively). Spain and Italy follow with 6 and 5 percent each. At the other end of the spectrum, four countries received less than 0.5 percent of the vote: the United Kingdom, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. If you then examine how different ‘subgroups’ – the ‘founding six, for example, or the Visegrad group – feel about this question, some slight differences emerge between them. For example, the founding six hold a more positive view of Italy, allocating it 9 percent of their vote compared to the 5 percent EU average. Obviously, policy elites in the old centre of the EU are more willing to acknowledge Italy’s former crucial role in integration than those who joined later.

A telling case is the assessment of the Netherlands. Here it seems the strong integrationist commitment in the past is assumed to continue by newer members, whereas the changing mood in the Netherlands on “more Europe” has been sensed by its long standing EU-partners: The Visegrad countries are the only ones to rate the Netherlands higher than the average (7 percent compared to 5 percent overall), higher than the other founding members or the Dutch respondents rate themselves (4 percent).

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to provide insights into the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. 548 respondents completed the question discussed in this piece.The full results of the survey were published in October 2018 in the EU Coalition Explorer. This interactive data tool helps to understand the interactions, perceptions and chemistry between the 28 EU member states, and is available at https://ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer.The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU, funded by Stiftung Mercator.

As sobering as the aggregate results are, the respondents to the ECFR survey have a more positive view of their country because they are closely engaged in the policy process and tend to see their own country differently. In particular, the results reveal a tendency to view one’s own country as more committed to deeper integration than others in fact think it. As the graph clearly indicates, in only nine member states does the self-assessment of the professional class match the general view. For example, what Germans think about Germany on this question is on a par with what others think about Germany.

Within this group of nine, Germany and France are unanimously regarded as committed to deeper integration, and see themselves as such too. The data shows that most other countries in this group come across as much less committed – and their peers agree that they are less committed. For example, Hungary’s self-assessment and the general view coincide exactly – 0 percent in both cases. Meanwhile, a mere five out of 3,761 votes cast for this survey question go to the United Kingdom, of which two come from British respondents. The views of oneself and from others also match well for countries that exhibit only a very weak commitment to more Europe. These include Denmark, the Czech Republic, Croatia, and Poland. Euroscepticism in these places is no secret: professionals here know first-hand of national reluctance vis-à-vis deeper integration, and so do their peers around Europe.

For the remaining member states, the research reveals that they all think themselves committed to deeper integration – but their counterparts disagree. Cyprus comes top in this regard, with a 12-point discrepancy between its self-assessment and what others think of it. Interestingly, Italy holds a rather high opinion of itself in this regard, with a self-assessment of 15 percent (the highest percentage level for this question), no fewer than 10 percentage points greater than the general view. However, neither the French and German respondents nor practitioners and experts elsewhere in the EU share this view of Italy. A gap nearly as wide also emerges for Spain and Portugal, with 10 and 9 percentage points respectively between what the Spanish and Portuguese think of themselves and what others make of them. Here too the national view of oneself is far more positive than the overall view.

Other member states with sizable gaps include the most recent EU joiners. For these, the survey findings contain a bitter message: among the older member states, newer members do not receive much credit at all for wanting more Europe. Estonia does best on this question, but even then it wins the recognition of only 4 percent of respondents overall. Baltic and Balkans members do regard themselves as pro-integration, however.

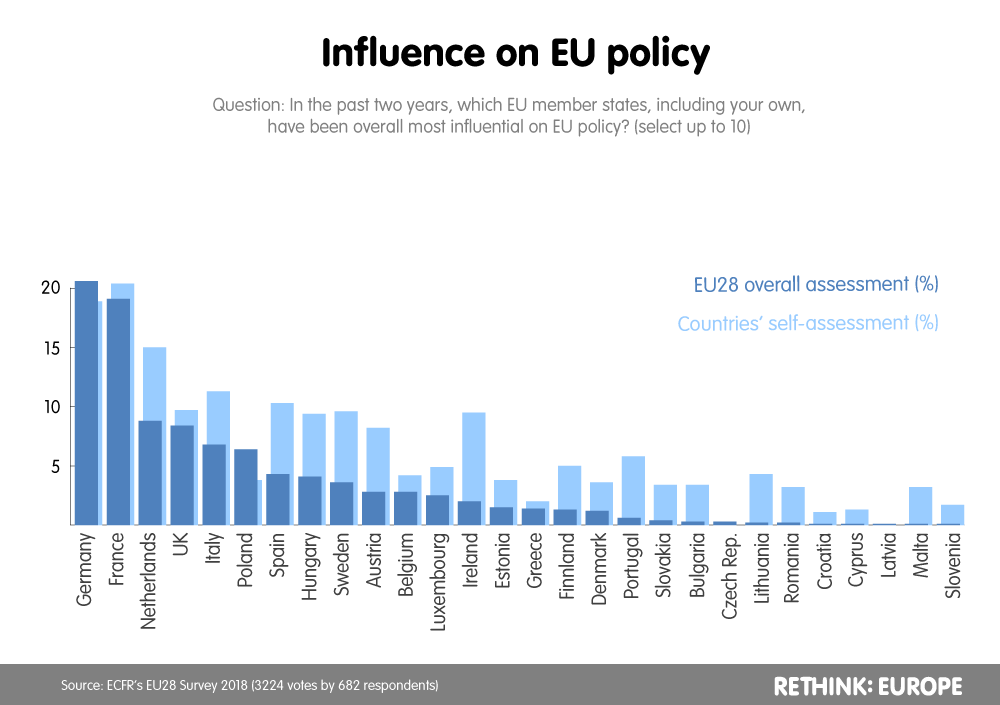

The tendency to overstate one’s own commitment to deeper integration corresponds with answers to another question of the EU28 Survey. When asked to name the EU member states that exert the biggest influence on EU policy in general, only Germany and France enter double digits, at 21 and 19 percent respectively. The Netherlands receives 9 percent, putting it in third place, while the UK and Italy sit on only 8 and 7 percent, with Poland just behind them on 6 percent. However, while French and Polish participants’ self-assessment matches the overall judgement, German respondents place their own country among the most influential less often than other member states do.

On the other hand, 10 out of 28 member states pick their own countries significantly more often than respondents as a whole do, with a difference of four or more percentage points above the average. Leading here is Ireland, which believes itself to be much more influential in EU policy than its peers do: its own respondents’ belief in this respect place the country 8 percentage points above the general view of Ireland. This may be a result of the prominence of the Irish border issue in the Brexit negotiations. Other capitals possessing a certain over-confidence in their own influence are The Hague, Madrid, and Stockholm, with a 6-percentage point difference above the general view.

In sum, the mood is better than the actual situation. Many countries see themselves as open to deeper integration but consider that others are not, except for the ‘core four’, which everyone views as integrationist: France, Germany, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Many also see themselves as having more influence on EU policy than their counterparts do, who instead single out Germany and France as the most integration-minded by far. In light of these figures, it comes as no surprise that the Franco-German tandem is the indispensable driver of integration policy, though the tandem alone is hardly a sufficient vehicle for moving integration ahead.

In today’s EU, enjoying the support of Belgium and Luxembourg in seeking more Europe is just not enough. Coalition-forming will have to take place by trying to integrate member states which have no principled enthusiasm for deepening integration. But this new research reveals that many of these countries hold themselves in high regard when it comes to their influence on EU policymaking. Obviously, views about what “more Europe” means differ between east and west. Without a common understanding of the trajectory of further integration, the apparent willingness to commit will be frustrated. In a similar way, overestimating one’s own influence on EU policymaking could backfire when put to the test on issues important to these countries. Do they risk a hard landing when they find themselves unable to wield the influence over the course of Europe’s future that they expect? Proponents of deeper integration should study these results carefully; they may need to deal with perceptions of power and influence as much as the reality of the questions themselves about how to integrate.

This article is part of the Rethink: Europe project, an initiative of ECFR, supported by Stiftung Mercator, offering spaces to think through and discuss Europe’s strategic challenges. For more information on the EU28 Survey and the EU Coalition Explorer, the tool presenting the results of the expert survey go to www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.