The “European army”, a tale of wilful misunderstanding

The European army concept is ambiguous – what do European leaders actually want to achieve?

The European Union is, under French leadership, creating a European army with a European nuclear force – one that is able to defend Europe against the United States.

Sounds unlikely? Congratulations! If you, dear reader, are baffled by the above statement, it means that you are not afflicted with the disorder currently raging through the transatlantic realm: that of wilful misunderstanding.

In the last few weeks, I have heard the above interpretation of a European army and European strategic autonomy several times – sometimes from people who should know better.

How did this happen? After all, the idea of a European army is at least 68 years old and appears in the European debate with some regularity, particularly in France and Germany. As Agnieszka Brugger, defence spokesperson for the German Green party noted at the recent Women in International Security in Germany conference, the German Bundestag discusses the European army at least once a year. It has been mentioned in German party programmes and coalition treaties. In 1996, then French prime minister Alain Juppé argued for a European army.

To load the audio player provided by Soundcloud, click the button below. This means Soundcloud will receive technical data about your device or browser, as well as information about your visit on this page. Soundcloud may use cookies and may transfer your data to servers outside the EU, where the level of data protection may not be equivalent to that in the EU. For more information visit our privacy policy.

The current debate on the issue primarily stems from a widely publicised radio interview with French President Emmanuel Macron. In the interview, Macron called for a “real European army” as part of his idea for “L’Europe qui protège” (a Europe that protects). German chancellor Angela Merkel reiterated the idea shortly after in a speech at the European Parliament: “we have to look at the vision of one day creating a real, true European army,” she told MEPs in Strasbourg.

“European army” is a term that is designed to be ambiguous. It is meant to inspire. The idea behind terms of this kind – “European strategic autonomy” is another – is to deliberately leave room for interpretation so that potential supporters can project their ideas into it and lend support to the concept, despite there being no agreement as to its actual meaning. During the 2016 British referendum on membership of the European Union, the Leave campaign had great success with this approach, presenting the term “Brexit” in a fashion ambiguous enough to appeal to 52 percent of the population – even though, to this day, there is no agreement on what “Brexit” means, (a fact that underlines the dangers of continued ambiguity).

But what worked for the “Brexit” term isn’t working for “European army”. Rather, the opposite is happening, with some people, including the American president, wilfully misinterpreting the term in the most extreme way possible – only to reject it. The European army has become an idea that many love to hate.

Unfortunately, President Macron has recently made this easier with a slightly awkward formulation. In the same interview in which he called for the European army, Macron said “we need to protect ourselves – from China, Russia, and even the US” (“nous devons nous protéger, a l’égard de la Chine, de la Russie, même des Etats-Unis.”). Some outlets translated this as “need to defend against”. However, he was not speaking militarily. Rather, Macron was discussing the rise of great powers and their interference in European affairs – against which Europe needed to protect itself. This was more than five minutes before he mentioned the European army, in the context of future “projects”. At that point, he added, “we need a Europe that is increasingly able to defend itself by itself – and without solely depending on the US.” His phrasing clearly shows that this is not directed against the US, but that he is trying to do exactly what Washington (as well as others) have called for: build up a Europe that does more by itself in the military domain without depending on the US for everything.

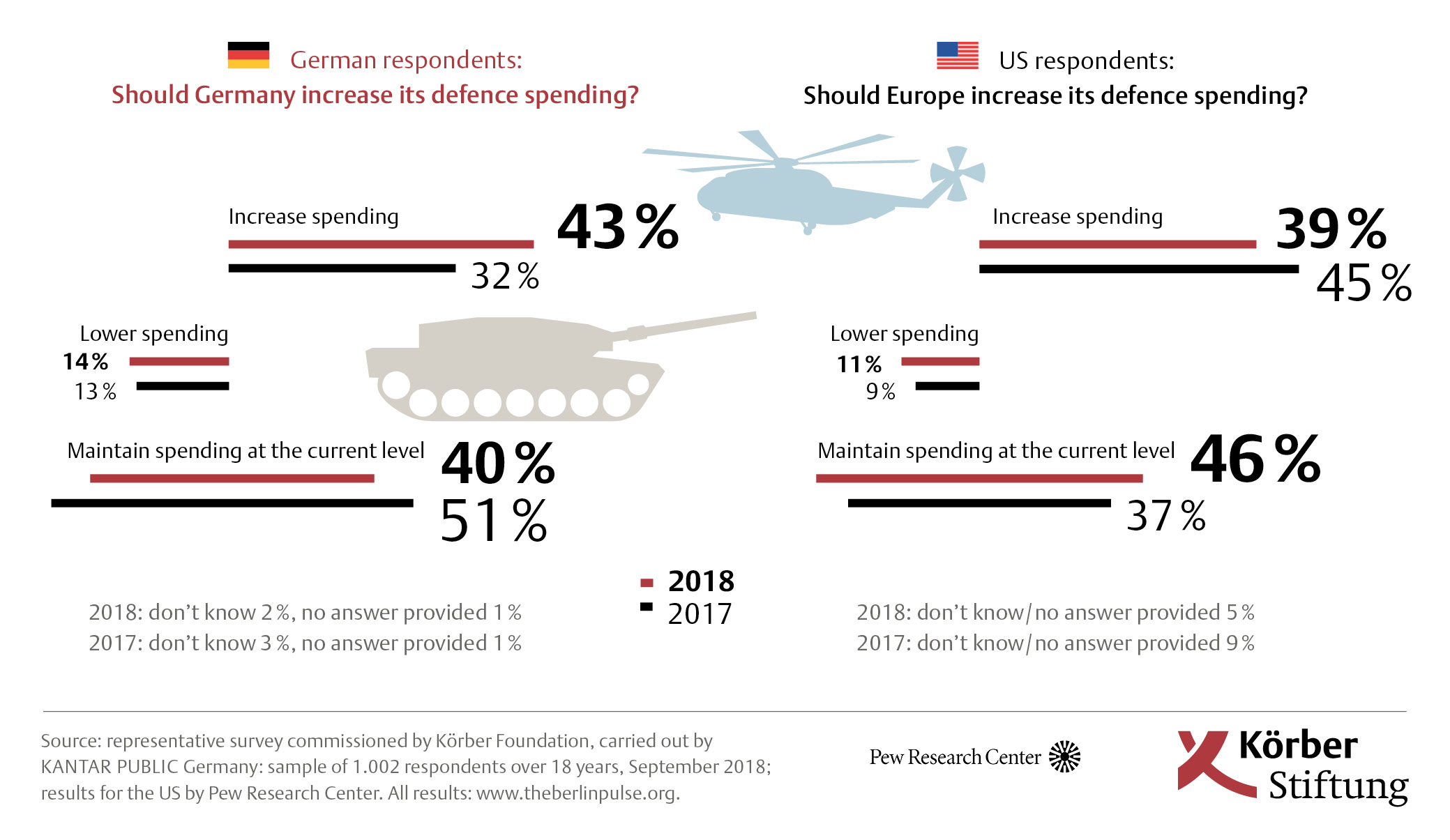

Initially intended as a rallying point, the European army idea is thus becoming a liability. Many military and political experts have grown tired of the concept and would prefer to retire it quietly. But, as I argued in the latest episode of Sicherheitshalber,[1] it is not enough for experts to reject the term and move on. This is because these misunderstandings have an impact on the real world. As a poll published in the 2018 Berlin Pulse shows, the number of Americans who support increased European defence spending has significantly dropped since last year, from 45 percent to 39 percent. And, last week, the European army debate even caused turmoil within the Dutch cabinet, when Deputy Prime Minister Kajsa Ollongren clashed with Defence Minister Ank Bijleveld over their respective support for and opposition to the idea.

It would, therefore, be useful if politicians such as Macron or German Chancellor Angela Merkel could be more precise in their rhetorical support for the long-term vision of a European army: what do they want to achieve, and when? Such precisions would likely reveal that the French and the Germans already have significantly different interpretations of a European army which would be worth addressing.

My sense is that the European army idea is similar in scope and ambition to the “United States of Europe” or former US president Barack Obama’s “Global Zero” (a world free of nuclear weapons). But, if the concept is a more substantive target for the current European defence procurement and coordination programmes, it is high time that European leaders explained what it would look like in greater detail. For the European army concept, strategic ambiguity is not working. To cure the affliction of wilful misunderstanding, we should abandon the ambiguity – or abandon the term.

[1] Sicherheitshalber is a co-production of ECFR and Augengeradeaus.net, the German podcast on Defence and Security. For all episodes of the series, see https://soundcloud.com/sicherheitshalber.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.