The challenge for Berlin in 2017

Berlin will need to manage the fears of its fellow members, especially in regard to three specific issues.

In his book The Churchill Factor, British foreign secretary Boris Johnson sets out Churchill’s role at the beginning of WW2 as the lone defender of European civilization against Hitler. Today, perhaps ironically for Mr. Johnson, it is Germany that is Europe’s last defence against nationalism. And the Brexit vote was the event that not only elevated the former mayor of London to a bigger job, but that highlighted the extent of the threat facing Europe.

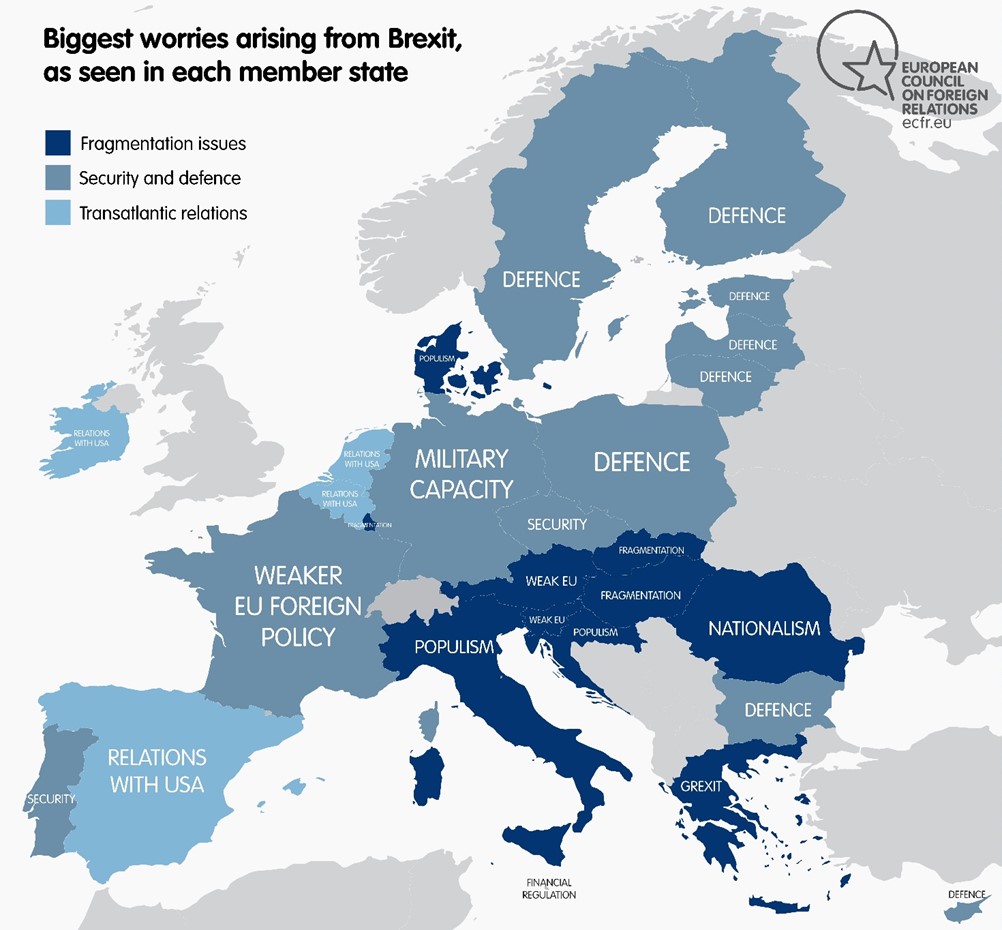

In a recent survey by ECFR of the political parties in all 28 EU member states on their perceptions of the EU’s current affairs, the consequences of Brexit figure high on their list of concerns. The states can be divided into three groups depending on their primary concern: those that fear the weakening of Europe’s security, others that fret about the fragmentation or even failure of the EU itself (as in the case of Hungary), and a third group that worries about future relations with the US without Britain as a bridge.

In dealing with all three sets of concerns, Germany’s role is and will remain crucial. In particular, Berlin will have to manage these fears with regards to three specific issues in the coming year:

- Dealing with Russia: Constructing common EU policy will become increasingly difficult, especially if Mr. Trump decides to strike a deal with Mr. Putin. In anticipation of this possibility, several member states have plans for rapprochement with Russia. Despite its de facto hard-liner role in the relationship, Germany will have to prevent an EU split over Russia, which will probably mean having to make some concessions. Isolating the discussion over the future of Ukraine (but possibly without Crimea) from any such deals will be key.

There will be voices in Berlin which will call for a German-Russian agreement of sorts, and the temptation to seek one will be significant. But Germany will have to balance EU unity and long-term interests over the short-term arguments for such a deal. The good news is that a wide-ranging US-Russian deal will not emerge easily: if Mr. Trump is a good businessman, he will soon discover that there is not much he can get in return for American gestures. Nevertheless, the commotion among member states will be significant and the sensitivities of eastern members like Poland will be exposed. Russia, on the other hand, will continue seeing the EU as a rival and Germany under Merkel’s leadership – the guardian of EU unity – as an enemy.

- Terrorism, migration and internal insecurity: The strongest factors in national politics will continue dividing societies and aggravating divisions in Europe. In order to prevent those problems from overlapping with other crises (as happened in 2016) Germany will have to overcome the impression around Europe that it is enforcing its own migration policy on Europe (‘Alleingang’). Stronger outer borders, quicker procedures for asylum applicants and a relocation mechanism acceptable to all member states will be needed. In addition, keeping the EU-Turkey deal intact will be critical: its failure could trigger a crisis of governance for a number of states along the Balkan route, including Bulgaria, Hungary and Austria.

- Marine Le Pen: If elected, Le Pen could trigger a ‘Frexit’ and subsequently a quick fragmentation of the EU. Planning for this contingency will not be easy but it already looks necessary. It will require mapping out the coalitions on the major issues which are vital for upholding the EU unity. As a next step, those coalitions should be put together in a loose structure that may not need – or be possible to institutionalise. In order to preserve the EU’s main principle of equality of big and small, those coalitions will have to be driven by a mixed group of countries, and in some cases Germany will have to act through proxies or even accept coalitions over which it has no say. The Visegrad format should be watched carefully as it has achieved significant autonomy and brings to the fore anti-German and anti-European ideas.

As the above makes clear, some out-of-the box thinking will be required, and Germany’s imagination will be put to the test. Defending the existing Europe is a task that Germany has been mastering well, but helping Europe move to the next stage will prove more difficult.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.