The roots of coalitions: Like-mindedness among EU member states

The EU28 survey explores Europe’s five power couples and potential strong bilateral partnerships

As the nineteenth century wore on, foreign policy in Europe increasingly became the preserve of cabinets rather than feudal rulers, calling into question bonds between royal families across the continent. As Lord Palmerston – a master of diplomacy in his time – observed, states do not have permanent friends; they have permanent interests. Today, Palmerston’s dictum seems only half true: the permanent interests he saw as key to foreign policy combine with other relevant factors – including principal values or preferences in rules and processes of engagement with others, as well as a shared history of cooperation and responsiveness. Together, these interests and other factors guide relationships and interactions between states.

In the early twenty-first century, Palmerston’s world seems to have made a comeback with a resurgence in geopolitics and great power rivalry. Nonetheless, the European Union has developed as a political system that could hardly be more different from the flexible alliances of his time. The Union integrates large and small member states into a common legal and institutional framework that often privileges the small, and that has tamed the power of the strong through the rule of law. But this does not mean that EU member states’ interests and preferences will always align with one another. Interestingly, a range of strong bilateral relationships and frustrated expectations shape the modern EU.

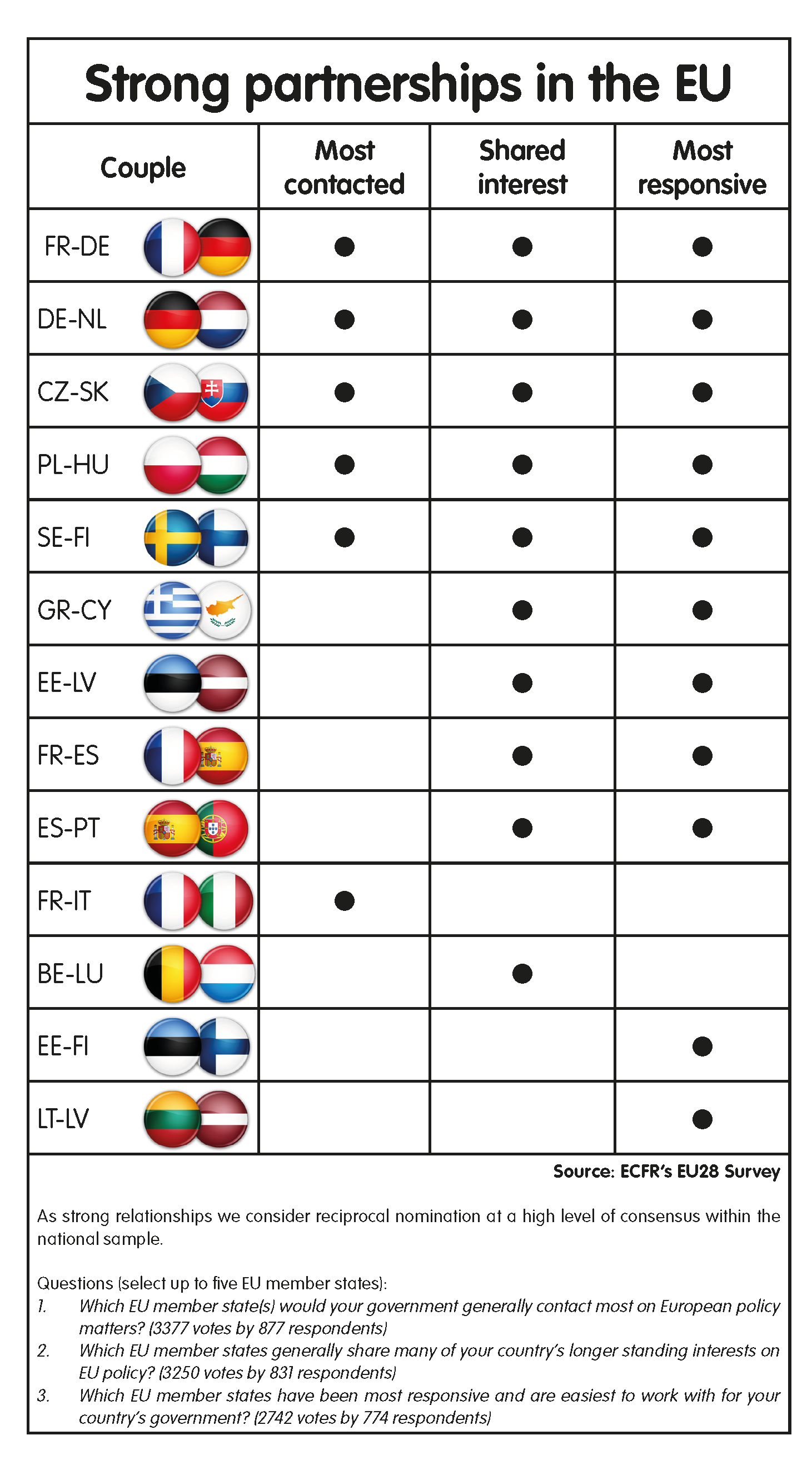

As demonstrated in the chapter on preferences in ECFR’s forthcoming EU Coalition Explorer, the Union encompasses a mixture of balanced and lopsided relationships. A strong relationship involves significant consensus and reciprocal engagement between two countries. For example, respondents from two member states in such a relationship listed their countries as having shared interests with each other significantly more often than they did with other EU countries.

Lopsided relations involve a high level of engagement by one side that the other does not reciprocate. For example, in the survey, 24 percent of votes from Danish respondents listed Sweden as responsive in dealing with Denmark, while only 11 percent of votes from Swedish respondents listed Denmark as responsive in dealing with Sweden. In votes Swedish respondents cast, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, and Estonia came out as more responsive than Denmark.

Like-minded countries

Judging by member states that have strong relationships, a shared neighbourhood often appears to be an essential factor in European integration. The survey demonstrated that France and Germany have positive relations across the board; each country recognises the value of working closely with the other, complementing all other member states’ recognition of them as key partners. Like the Franco-German tandem, the relationship between the Netherlands and Germany is balanced and strong, as is that between Sweden and Finland.

The only other pairs of countries that are highly responsive to each other across the board are members of the Visegrád group. Poland has formed a robust partnership with Hungary, as has the Czech Republic with Slovakia. There is an extremely high level of consensus within each pair, but the survey indicates that there is no comparable consensus between them. This suggests that the Visegrád group is a 2+2 relationship that includes some inbuilt rivalry and disagreement – which could significantly constrain its members’ collective impact. While the relationships between Baltic states are close, they are not always balanced. Although the survey provides further evidence that Greece and Cyprus have a close relationship, it also leads to the surprising conclusion that Spain is more closely connected to France than Italy.

Denmark, Austria, Ireland, Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, and Slovenia appear to have no close partners in the EU. Meanwhile, Belgium, Luxembourg, Italy, and Lithuania seem to have only one close partner each. Thus, these countries have relatively weak or unbalanced relationships with other member states. For example, Ireland most often contacts the United Kingdom and Germany, but the UK and Germany most often contact countries other than Ireland. Similarly, the Irish perceive themselves as having greater shared interests with the Dutch than the British, but the Dutch do not perceive themselves as having significant shared interests with the Irish. The UK and the Netherlands top Ireland’s list of most responsive partners – a perception that that the UK moderately agrees with, but the Netherlands does not.

Disappointing EU member states

The EU28 survey also reveals which member states are the greatest source of disappointment for EU policymakers and experts. For example, French respondents cast 5 percent of their votes for Germany, while no German respondent’s vote reflected disappointed with France. French respondents showed greatest disappointment with Poland, which received 22 percent of the votes from France. German respondents cast 22 percent of the votes each for Hungary, Poland, and the UK.

Percentage figures reflect the share of votes in each national sample. Questioned about which EU member states were most contacted, like-minded, and responsive, respondents to the EU28 survey could select up to five countries other than their own. Shares of more than 20 percentage points indicated a high level of consensus within a national sample.

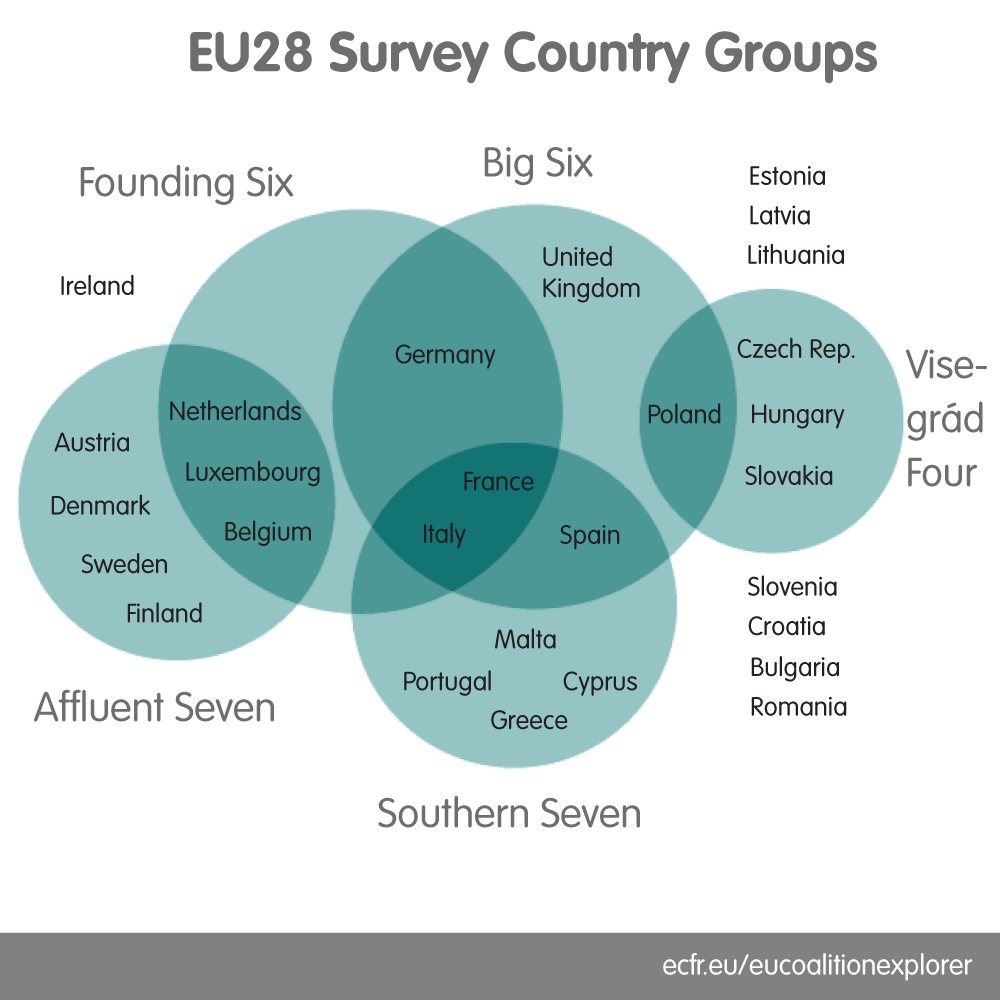

Across the EU as a whole, respondents perceived Hungary as the most disappointing member state by far, and Poland and the UK as equally the second most disappointing. Although respondents in 2016 saw Greece as one of the greatest sources of disappointment, this perception has now faded. These trends apply to various groupings of member states: the founding six, the six large states, the seven affluent small countries, and the seven southern member states. Yet they do not apply to the Visegrád group, whose members were most disappointed with France, Germany, and the UK (largely due to Budapest’s and Warsaw’s very negative views of Paris and Berlin).

Other deviations from the trend reflect specific issues in bilateral relationships. This can be seen in votes on the countries that disappointed respondents most, in which 18 percent of Spanish votes listed Belgium (reflecting the fact that Belgium hosted Catalan politician Carles Puigdemont), 33 percent of Slovenian votes listed Croatia (due to a dispute over a border in the Adriatic Sea), and 27 percent of Bulgarian and Romanian votes listed the Netherlands (likely because of a disagreement over Schengen access).

Coalitions of like-minded EU member states

These patterns of admiration and disappointment play an important role in EU coalition-building. In a way, strong bilateral ties are the basis for large coalitions. In 2018, these ties bind Germany and France to the Netherlands and Spain, Sweden and Finland to the Baltic states, Poland to Hungary, and Slovakia to the Czech Republic. Judging by the results of the EU28 survey, Germany and France are more effective at building coalitions than other member states. This is due to their uniquely high levels of interaction with their EU allies, and the widespread perception within the Union that they are the most influential member states and the most important partners in integration initiatives.

Yet there is more to the EU than these coalitions, which centre on the relationships that respondents either mentioned most often or saw as involving an unusually strong consensus. Moderately high levels of interaction and/or like-mindedness between countries – indicated by 10-20 percent of the share of votes of a national sample – are also important. These ties help explain why the Visegrád group is able to effectively veto EU policies but not to set the EU agenda: its two sub-groups can agree on some of the things they dislike, but are too different from each other to cooperate on more constructive efforts.

Meanwhile, lopsided relationships are also relevant to the chemistry between member states, because they reflect countries’ political aspirations and frustrated expectations. For instance, as the EU’s newest member state, Croatia has yet to integrate with pre-existing networks of member state governments. For example, Austria receives 19 percent and 21 percent of Croatian respondents’ votes on shared interests and responsiveness respectively – but only 2 percent and 6 percent of Austrian votes on these measures went to Croatia respectively. There was a similar asymmetry between Austrian and German respondents: the former looked to Germany far more often than the latter looked to Austria.

Denmark provides another example of imbalance. Seemingly due to Brexit, Danish respondents no longer referred to UK as their country’s top partner in 2018 as they had two years earlier. Moreover, Copenhagen’s other main partners were less focused on Denmark than it was on them – although the mismatch was less profound than in the cases of Croatia and Austria or Austria and Germany. While German respondents only occasionally referred to Denmark, it receives at least moderate shares of the vote (between 10 percent and 20 percent) from Sweden and the Netherlands.

Against this background, coalition-building strategies designed to broaden participation in EU policy initiatives will only be effective if they adequately address such gaps in reciprocity. By integrating member states into existing coalitions, these strategies could help such countries overcome their frustrations and lend new momentum to the European project.

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to explore the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. 730 respondents completed the questions discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey were published in October 2018 in the EU Coalition Explorer. This interactive data tool helps to understand the interactions, perceptions and chemistry between the 28 EU member states, and is available at https://ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU, funded by Stiftung Mercator.

This article is part of the Rethink: Europe project, an initiative of ECFR, supported by Stiftung Mercator, offering spaces to think through and discuss Europe’s strategic challenges. For more information on the EU28 Survey and the EU Coalition Explorer, the tool presenting the survey results, go to www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.