Migration through the Mediterranean: Mapping the EU response

The Mediterranean and migration: Postcards from a ‘crisis’

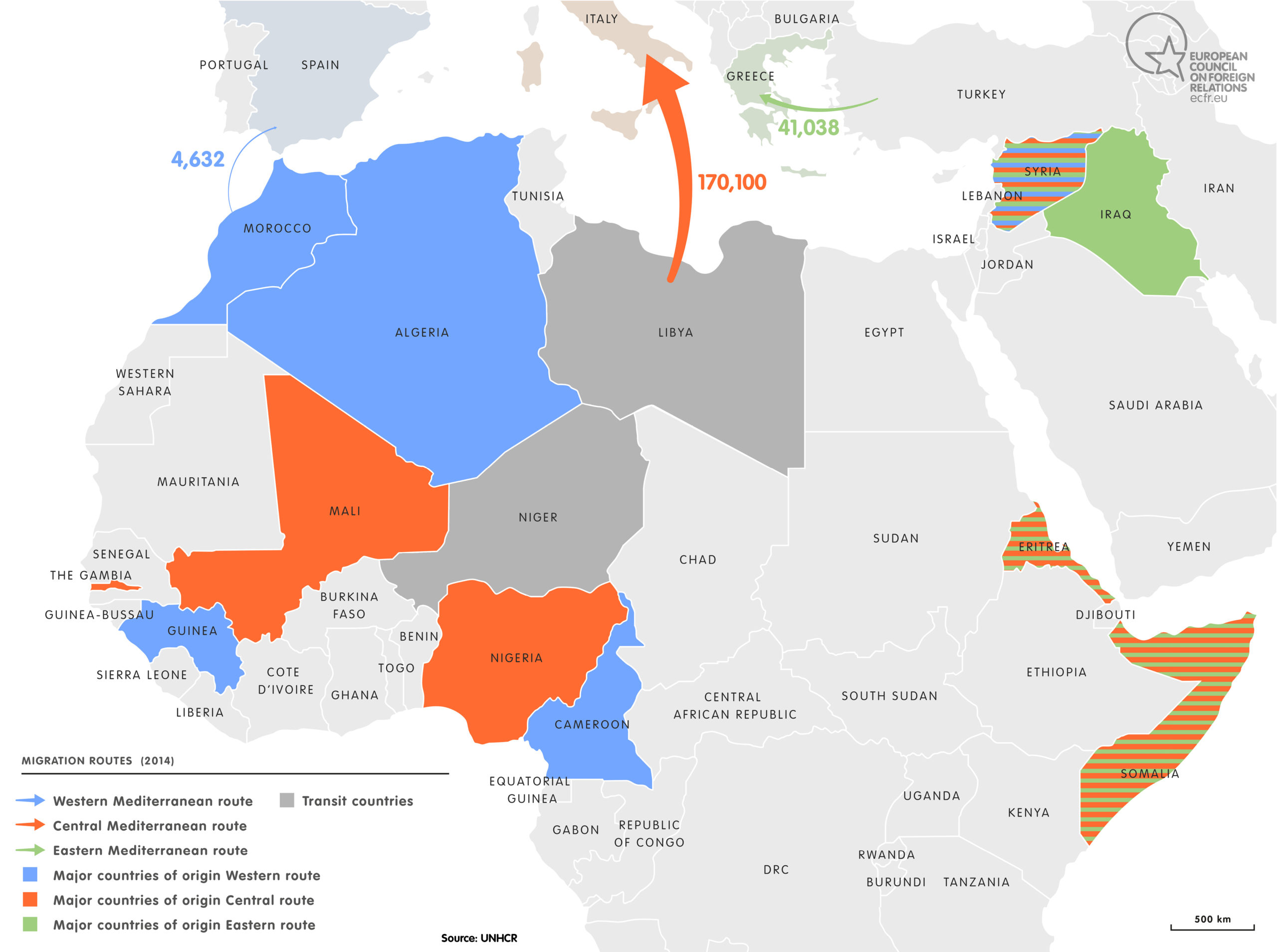

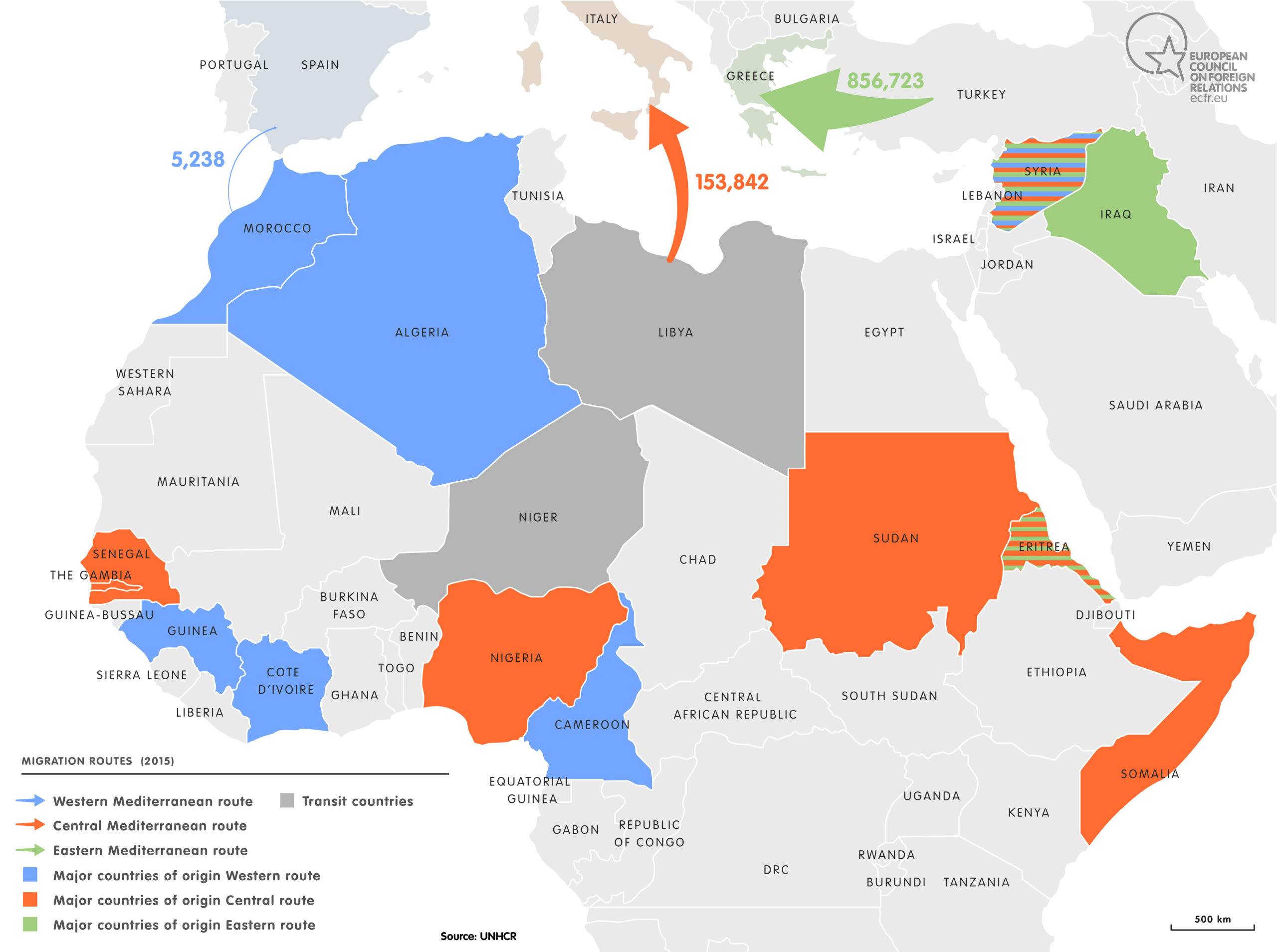

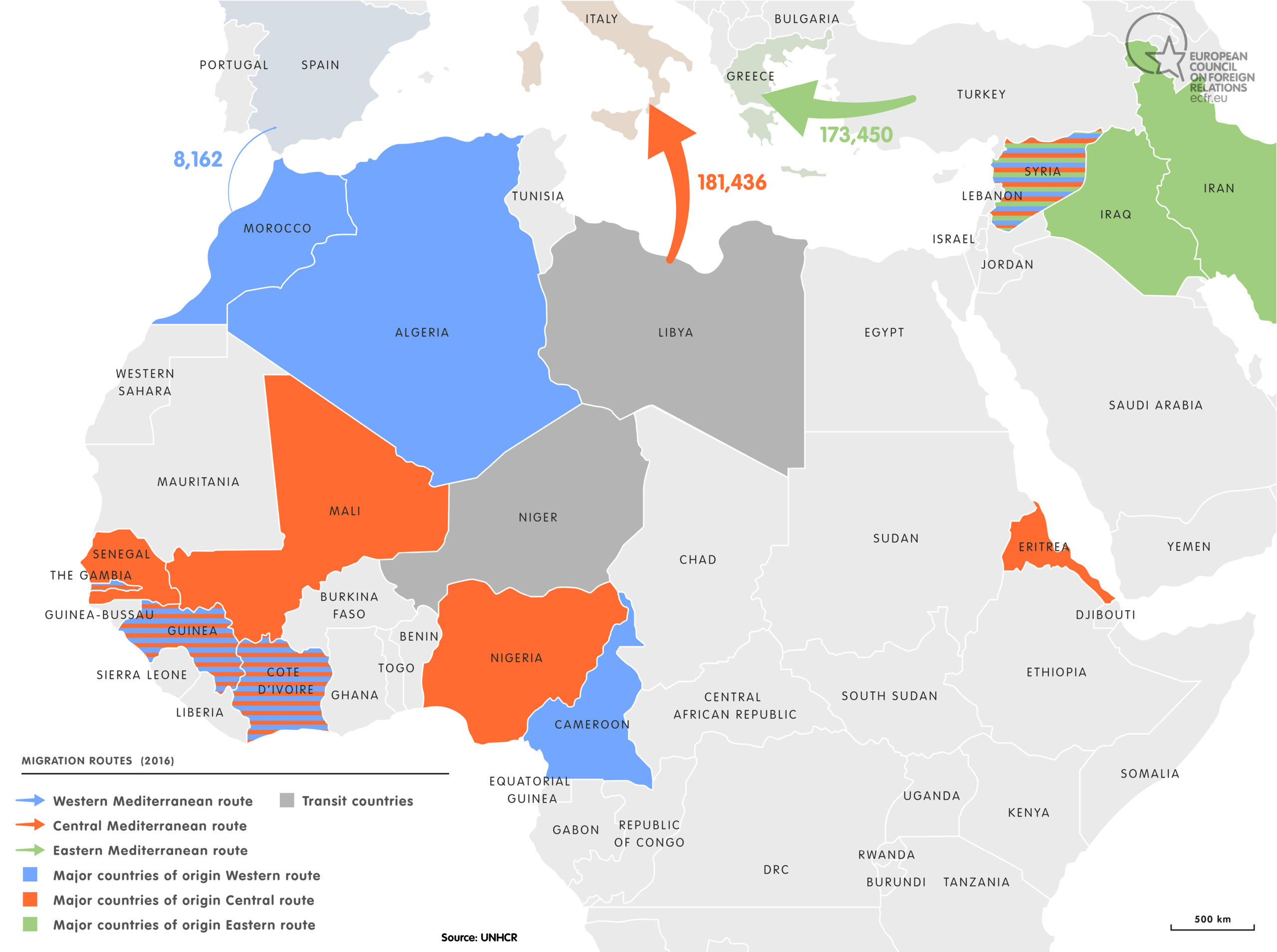

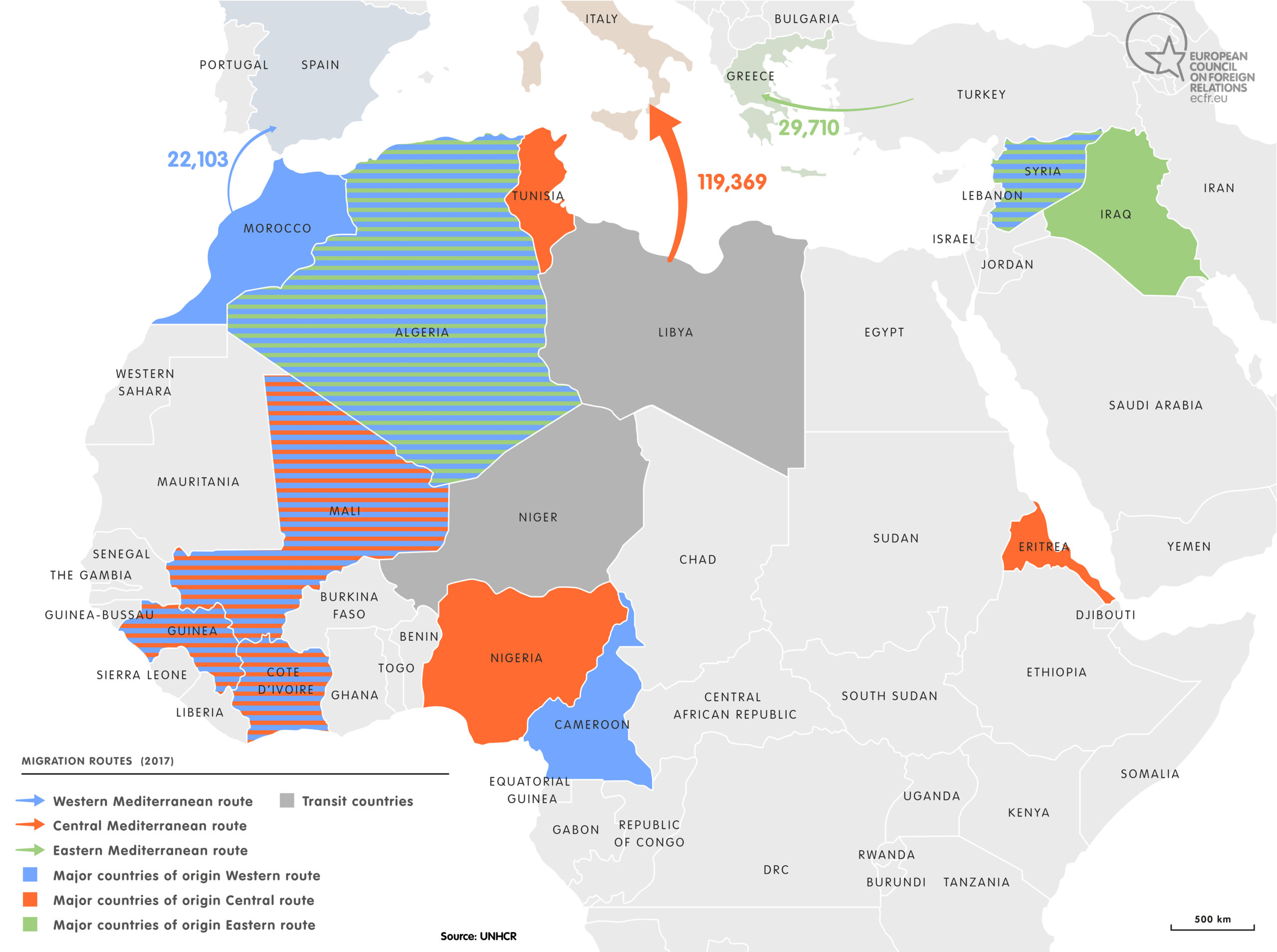

Since 2014, European citizens have been engaged in an intensifying discussion about migration. This is the result of an unprecedented increase in the number of refugees and other migrants entering Europe, many of them fleeing protracted conflicts in Africa and the Middle East, particularly the war in Syria. The phenomenon peaked in 2015, when more than one million people arrived in Europe, a large proportion of them having travelled along the eastern route through Turkey, Greece, and the Balkans. The number of arrivals has fallen significantly since 2016, albeit with more than 160,000 people reaching Europe through Mediterranean routes annually. As a consequence of their geographical position and the Dublin Regulation – which sets the procedures for asylum applications in the European Union – countries of first arrival Italy, Greece, and, to a lesser extent, Spain have been most affected. The growth in the number of arrivals has created the perception of an unmanageable crisis and made the public increasingly aware of the issue. Thus, the issue of migration has had great influence on elections held in Austria, France, Germany, Italy, and other European countries in the past year, boosting support for populist and eurosceptic parties. As shown in the maps below, patterns of migration tend to be very fluid and to change rapidly. Nevertheless, the central Mediterranean route has been one of the most consistently busy; the route to Greece has undergone significant changes; and, since 2017, the western Mediterranean route to Spain has been used much more than in previous years. This does not mean that traffic across other routes has been diverted to the western one, as primary countries of origin have also changed. For example, arrivals in Spain could be linked to the deterioration of the socio-economic situation in Algeria and to the political tensions in the Rif region of Morocco, while the opening of a new route from Tunisia to Italy appears to stem from the difficulties that other North African countries are experiencing.

2014

2015

2016

2017

Through the eyes of migrants

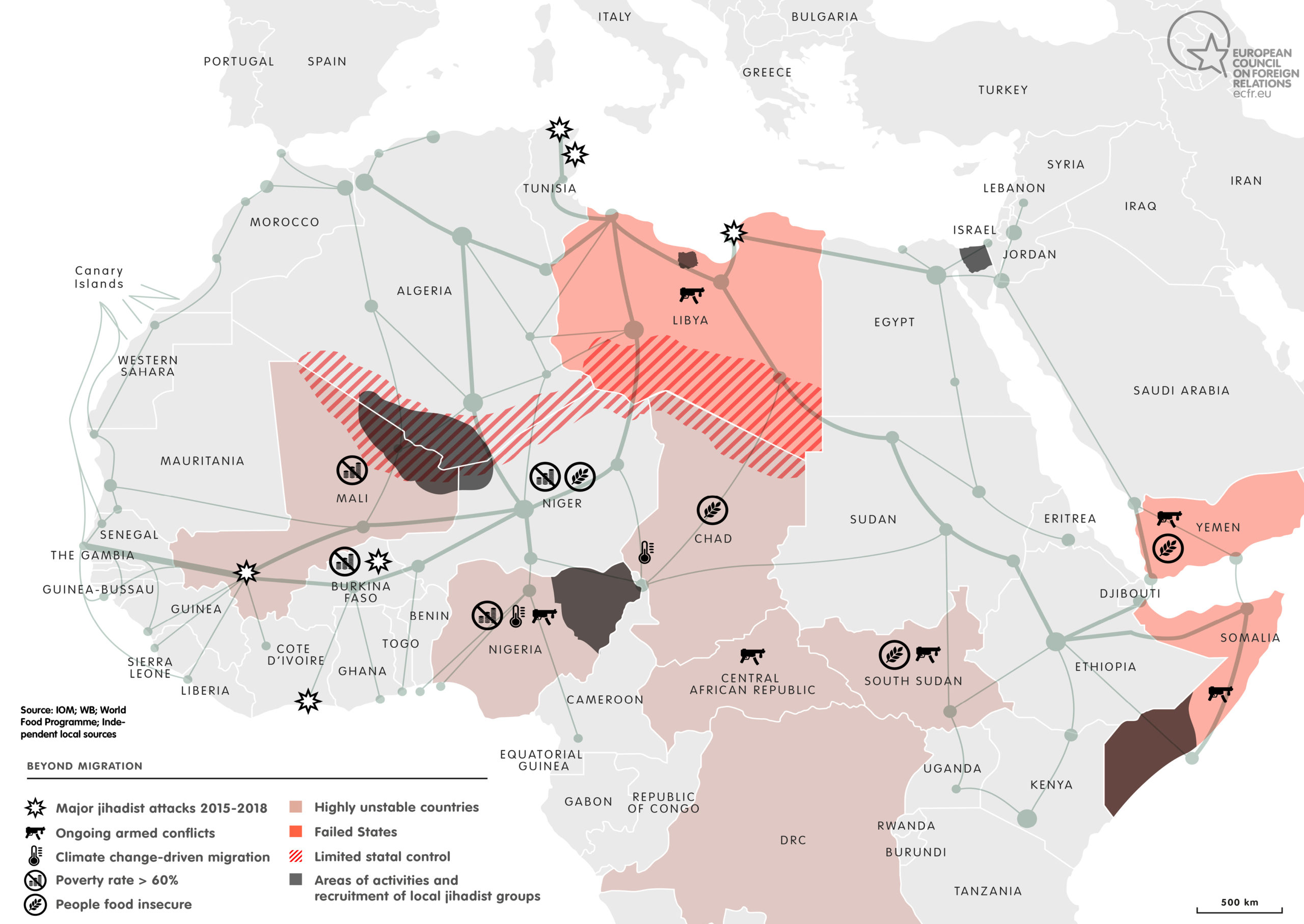

Many Europeans are unaware of the challenges migrants face before reaching the coast of Libya and crossing the Mediterranean. A large proportion of migrants, most of them from sub-Saharan African countries, endure a long journey in extreme conditions during which some of them die. Niger is the main hub on the route to North Africa. The agreements with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) make people move freely within Western Africa up to Niger. However from Niger northward, migrants are branded as “illegal” and are so forced to rely on smugglers and traffickers to reach Libya and Algeria. Migrants often travel to Europe – many of them having been forcibly displaced – due to armed conflict in places such as Syria, Yemen, and northern Nigeria. But there are also other factors behind the recent rise in migration, the most important of which is Africa’s population boom.

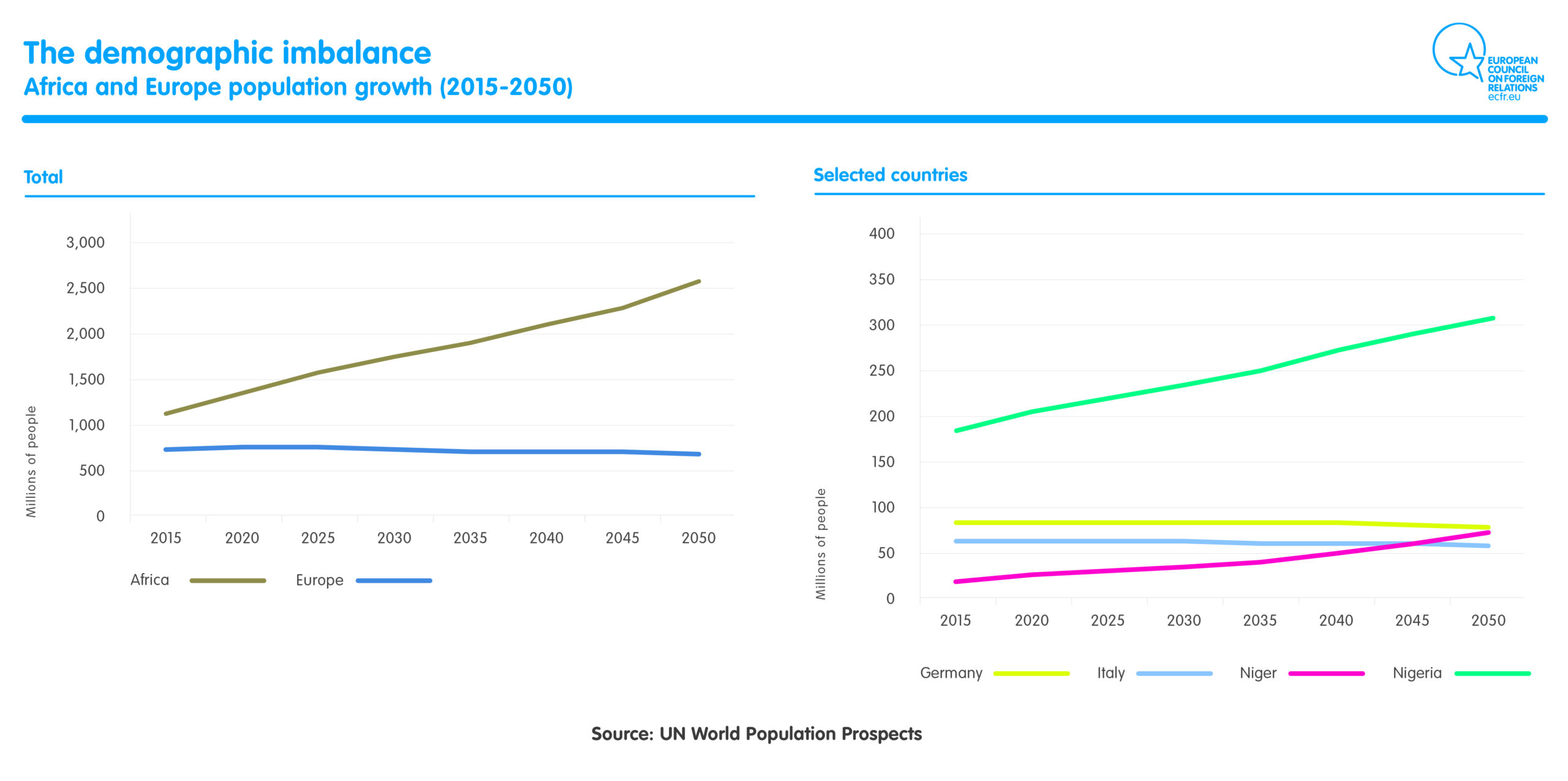

The continent’s population will double over the next 30 years because of very high fertility rates. Indeed, Niger has the highest fertility rate in the world: 7.3 children per woman. There is the opposite trend in Europe, which will have to address the challenges posed by an ageing population if it wants to maintain its current levels of prosperity. Beyond demographics, there are several other drivers of migration. Climate change is displacing large numbers of Africans, as reflected in trends in Nigeria and the Lake Chad region. Extreme poverty, food insecurity, and the predatory behaviour of authoritarian regimes also prompt people to flee their country to find alternatives both within Africa itself (about 90% of African migrants remain on the continent) and in Europe. Many are also displaced by the jihadist groups operating in order regions, such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and affiliated groups in the Sahel, and Boko Haram in northern Nigeria.

Niger in focus

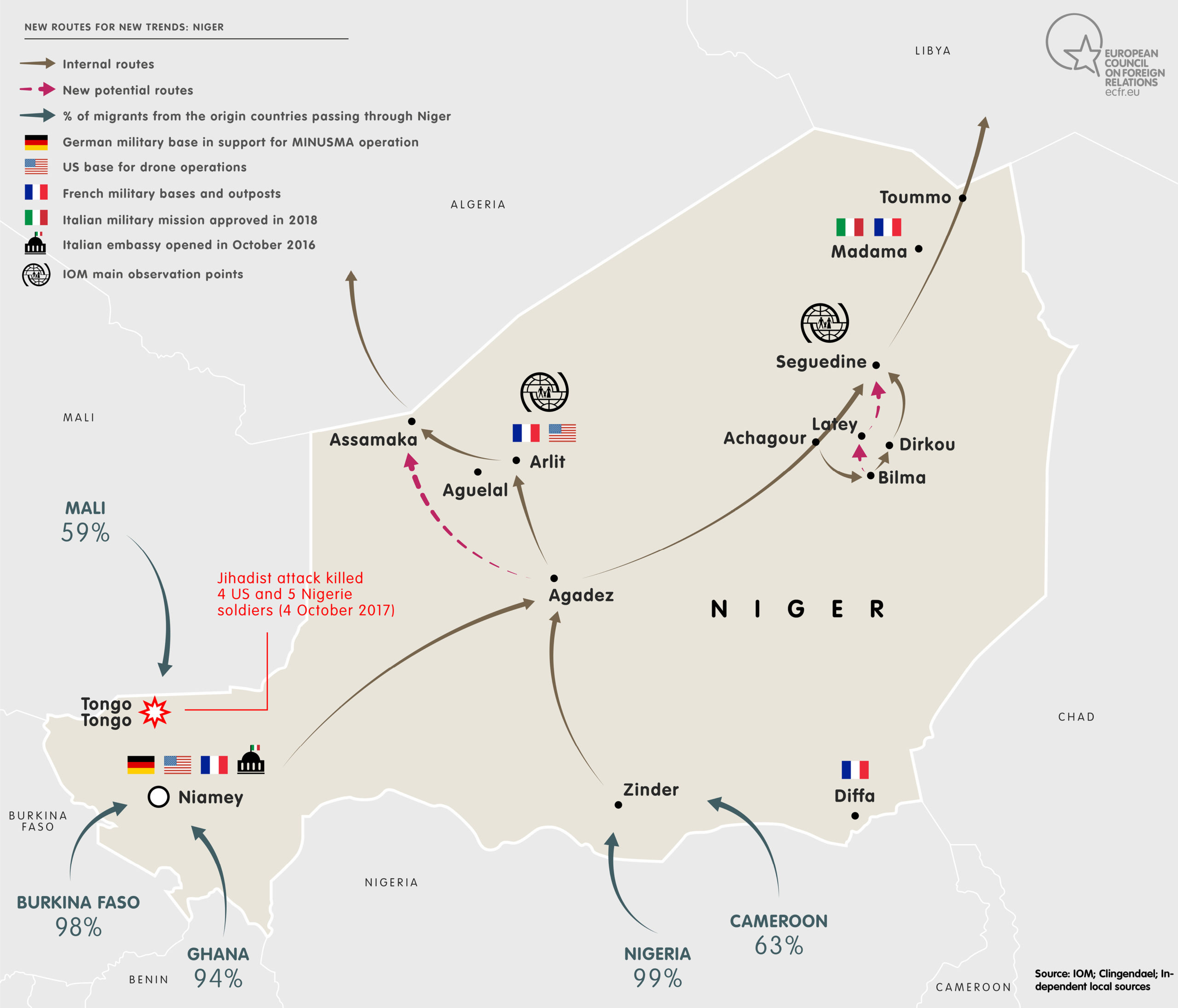

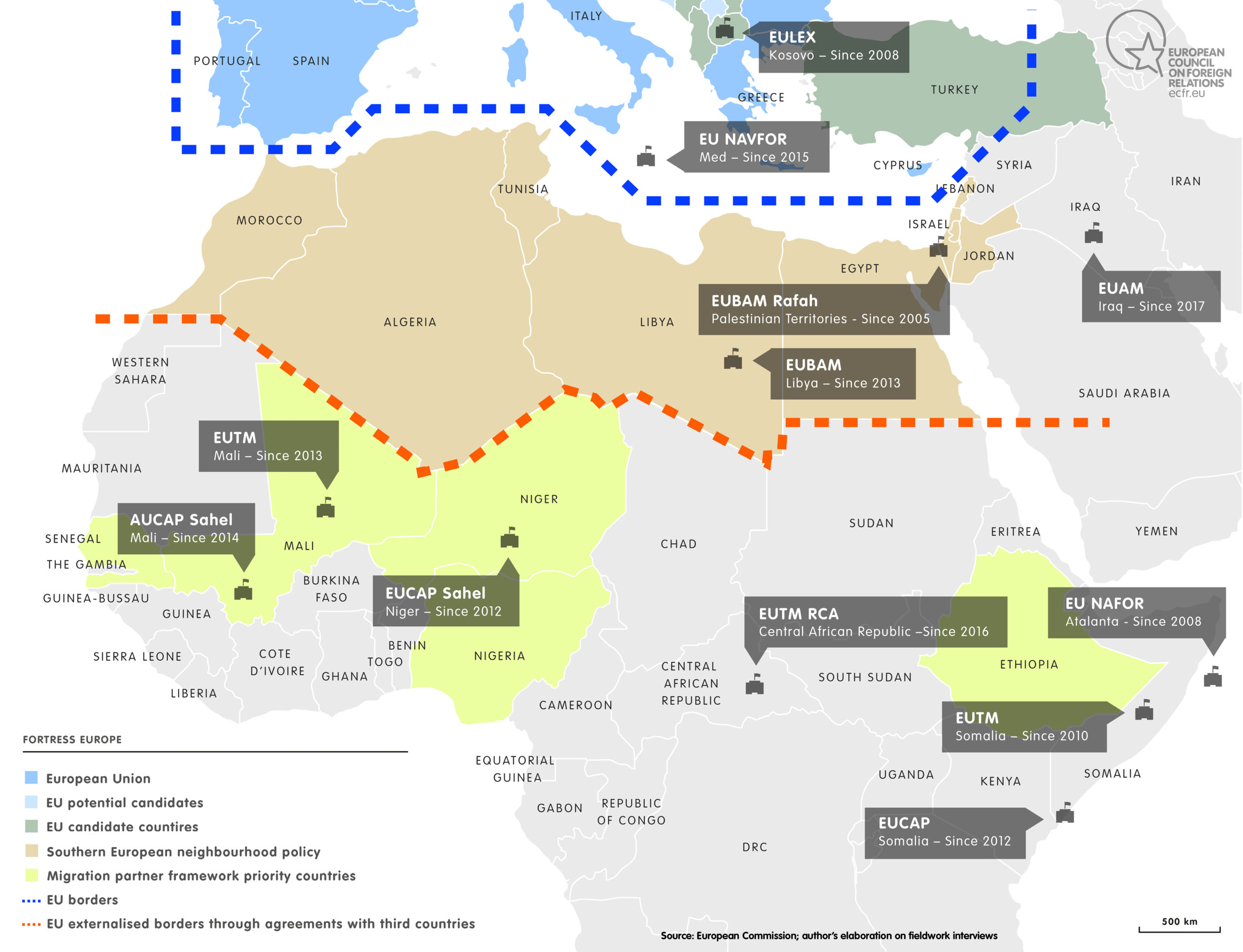

Faced with large numbers of people crossing the Mediterranean in recent years, the European Union has struggled to manage the phenomenon. As citizens become increasingly sensitive to the issue of migration, European governments have tried to provide immediate solutions to what is a long-term, structural shift. In this context, Niger became one of the first countries the EU engaged with, due to its position at the heart of migration routes to the Mediterranean. European countries’ activism in Niger involved the deployment of French and US troops there, along with activities at a German base in Niamey and the deployment of Italian soldiers in Madama (the last outpost for migrants travelling north before they reach Libya).

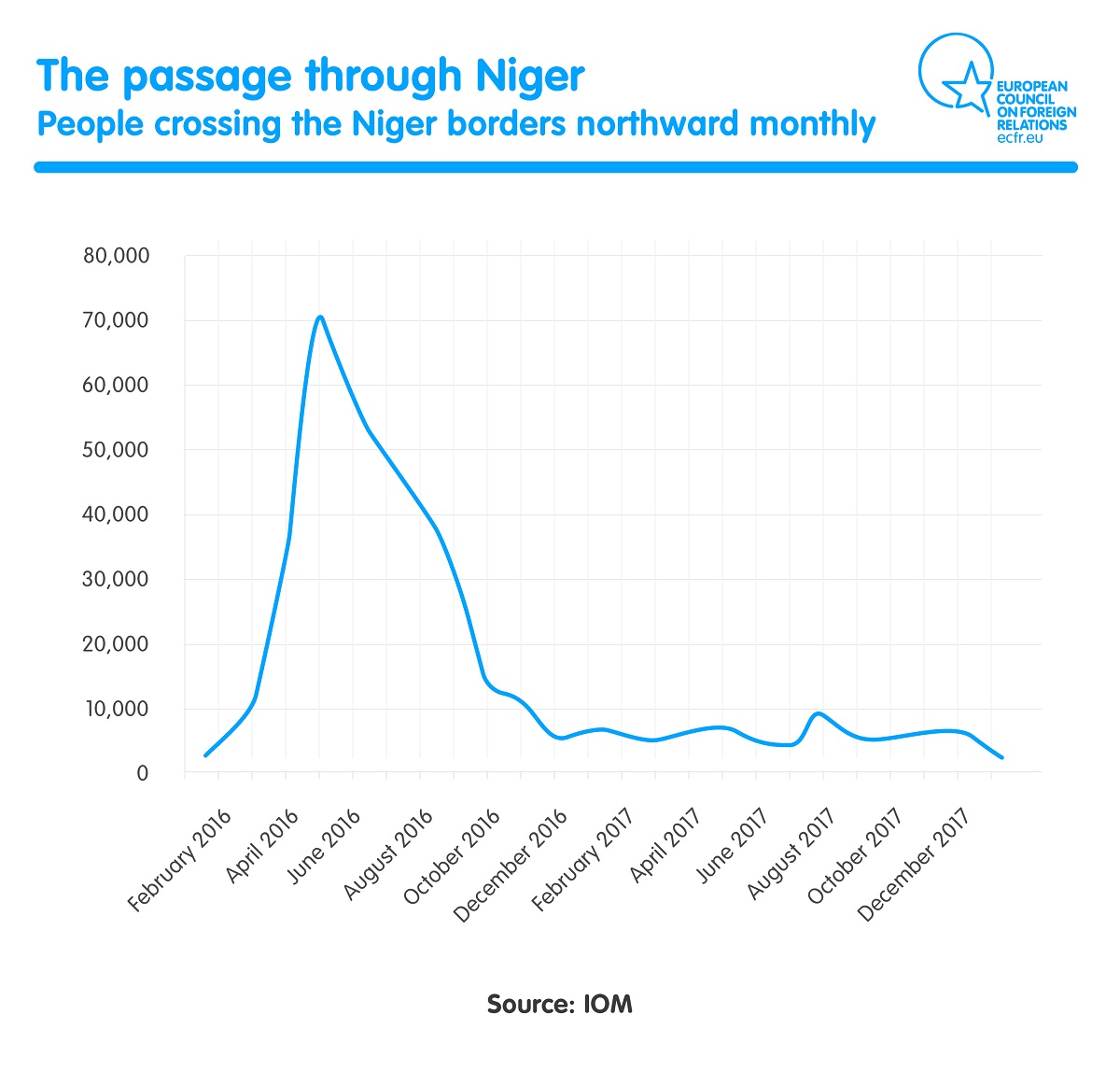

Aiming to stop migrants entering Libya from Niger, the EU has pushed the Nigerien government to adopt Law 2015/36, which criminalises people smuggling. However, this has had a counterproductive effect on the ground: although dozens of people have been arrested and dozens of vehicles confiscated since 2016, the law has destroyed the livelihoods of hundreds of people who involved in this informal economy without providing them with alternatives. As such, the law has exacerbated poverty and pushed migrants towards more dangerous routes and services. In fact, while the data collected by the International Organization for Migration shows a sharp decline in the number of people crossing the border between Niger and Libya since 2016, local sources confirm that the routes have simply adapted to the new context and that migrants continue to make the journey to Algeria and Libya.

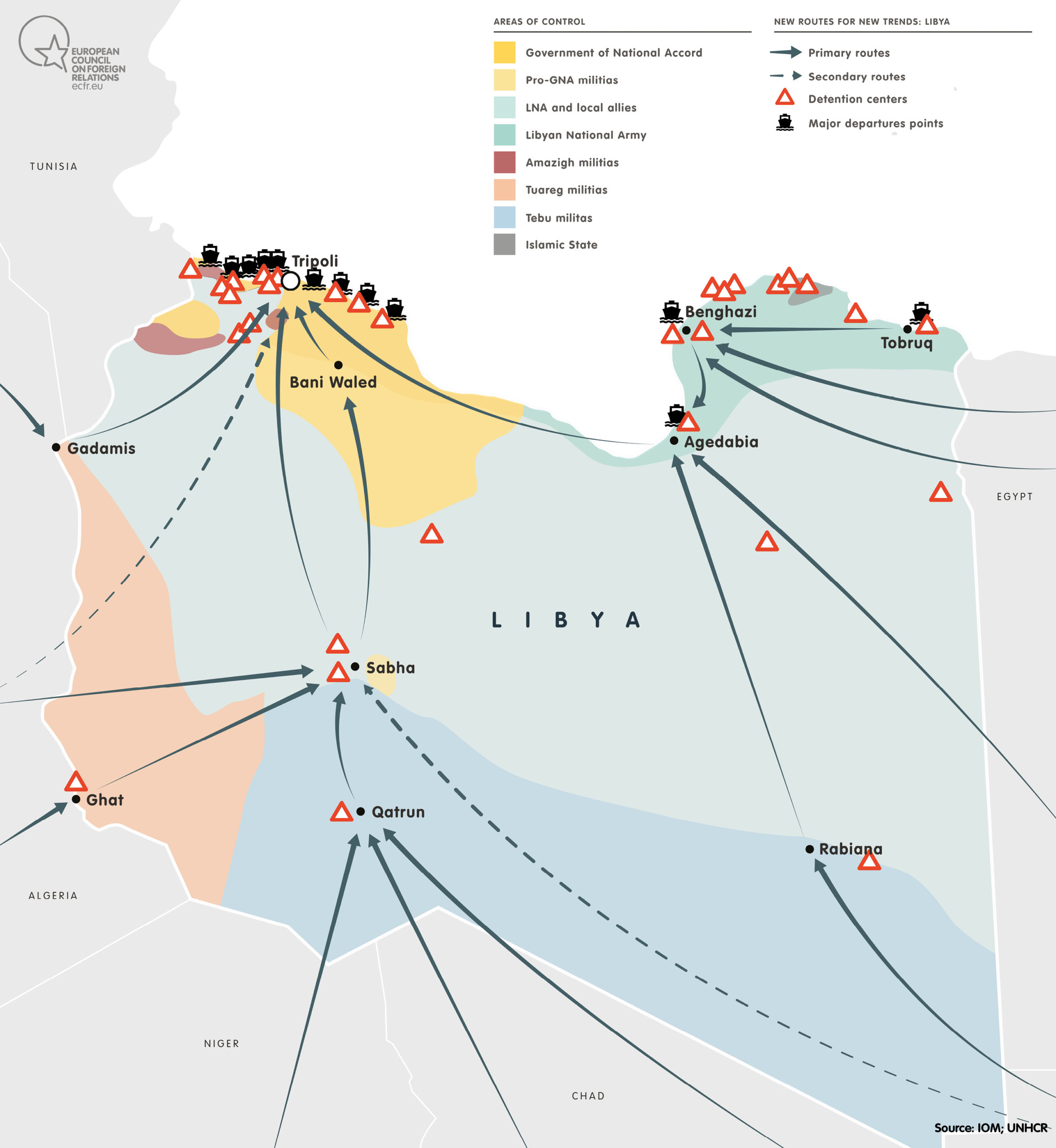

Libya in focus

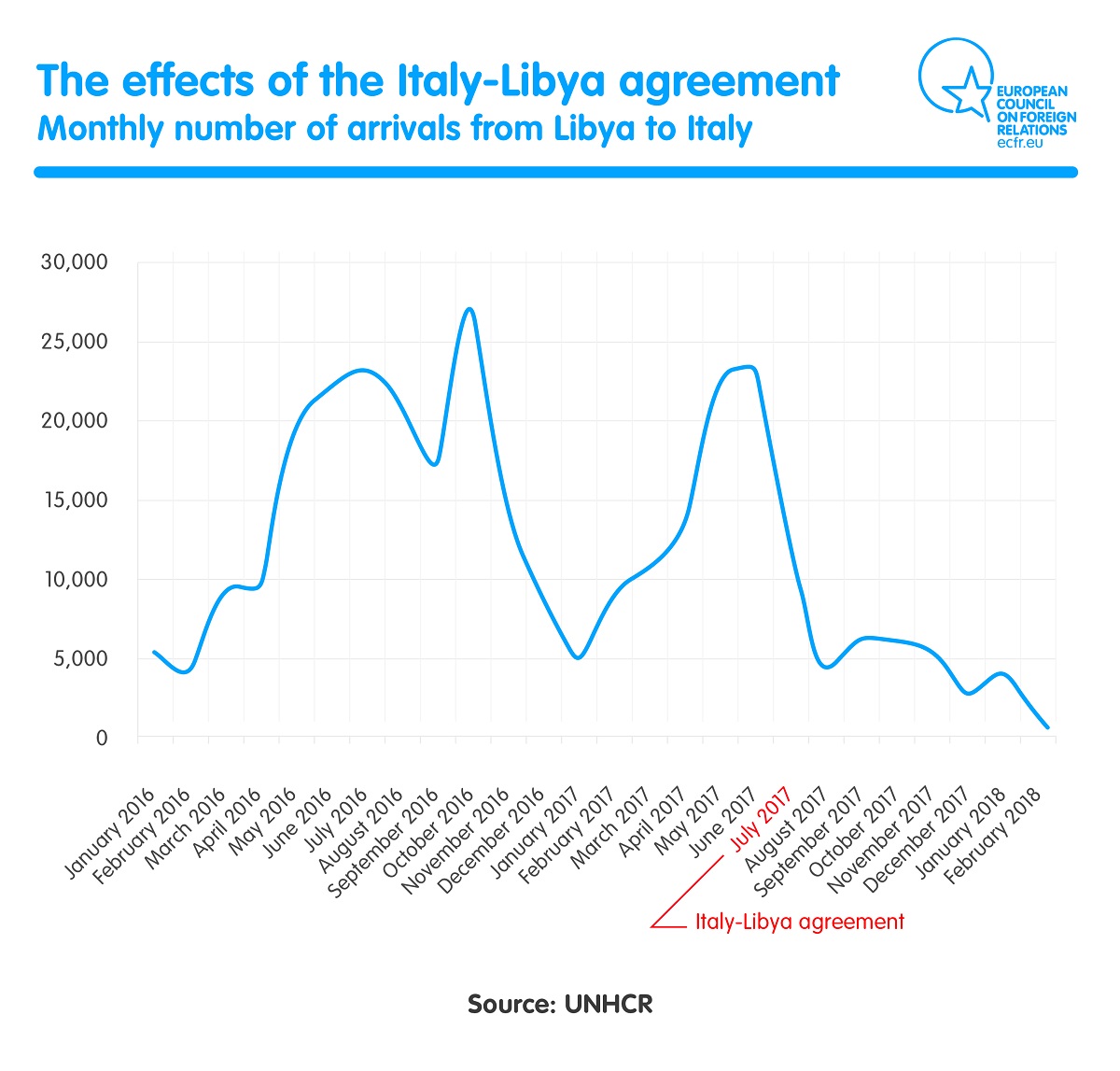

European, particularly Italian, policy on Libya has concentrated almost entirely on blocking the departure of migrants travelling to Italy without properly addressing the causes of migration. While this security-driven approach has proved effective in reducing the number of arrivals in Italy since summer 2017, these are short-term policies that do not represent a stable solution.

Quite the reverse: through these agreements, the Italian government unintentionally increased the political power of Libyan non-state actors, by indirectly involving armed militias, local authorities and the coast guard, whose roles often overlap. Furthermore, profiteers of detention centres have simply replaced profiteers of human trafficking. As reported by several organisations, in these facilities migrants frequently suffer physical and psychological abuse, as well as extortion. There are more than 30 official detention centres in Libya, along with an unspecified number of unofficial centres. The situation is made even more complicated by the country’s persistent internal conflict and the activities of dozens of armed militias affiliated with its protagonists. In Libya, there are more than 700,000 migrants, including almost 50,000 asylum seekers and 165,000 internally displaced persons. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees had begun to relocate asylum seekers from Libya to Niger and then to Europe, but the effort has stalled since last October: out of 1,300 people transferred to Niger, only 300 have been relocated to Europe, most of them to Italy.

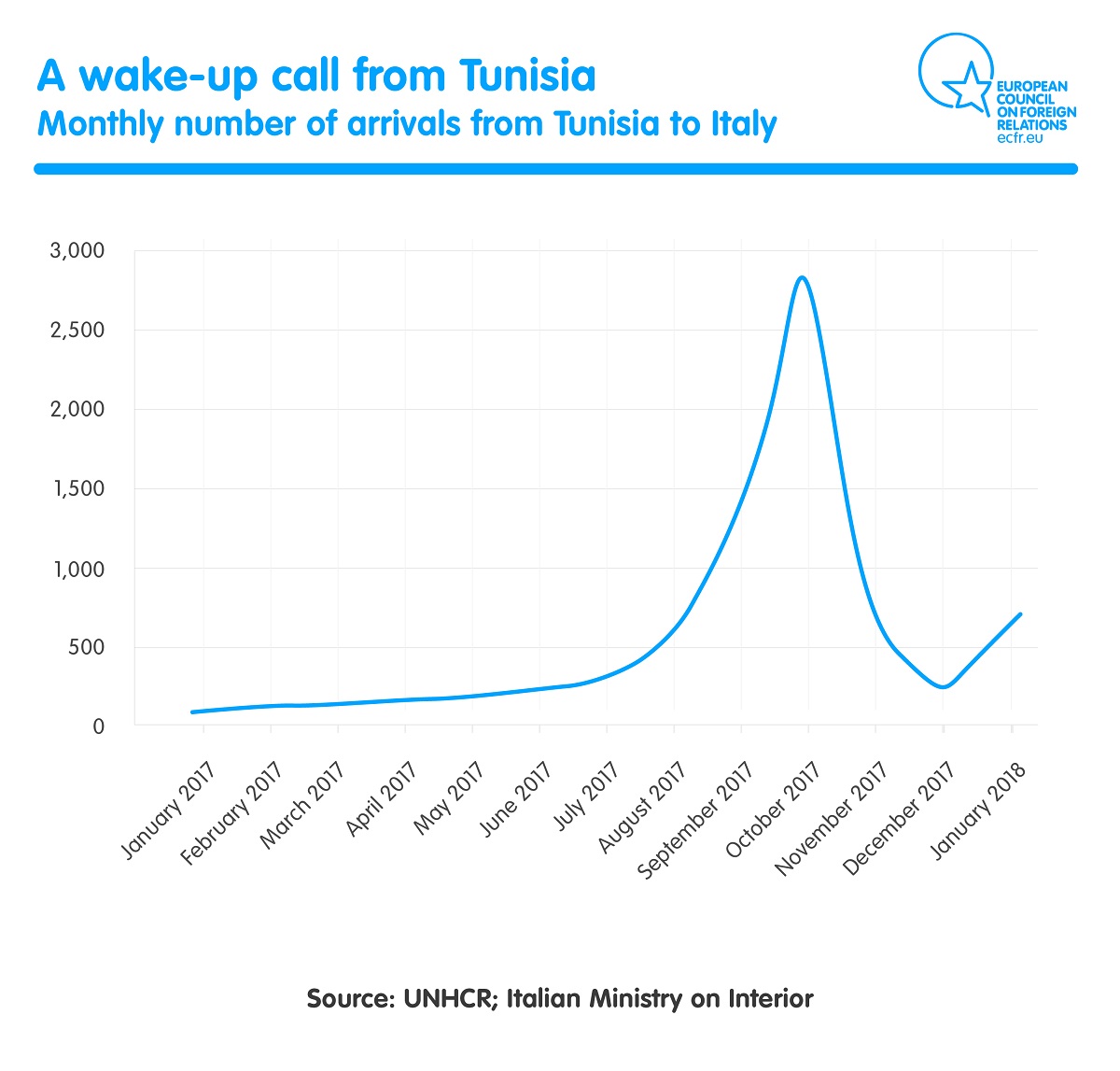

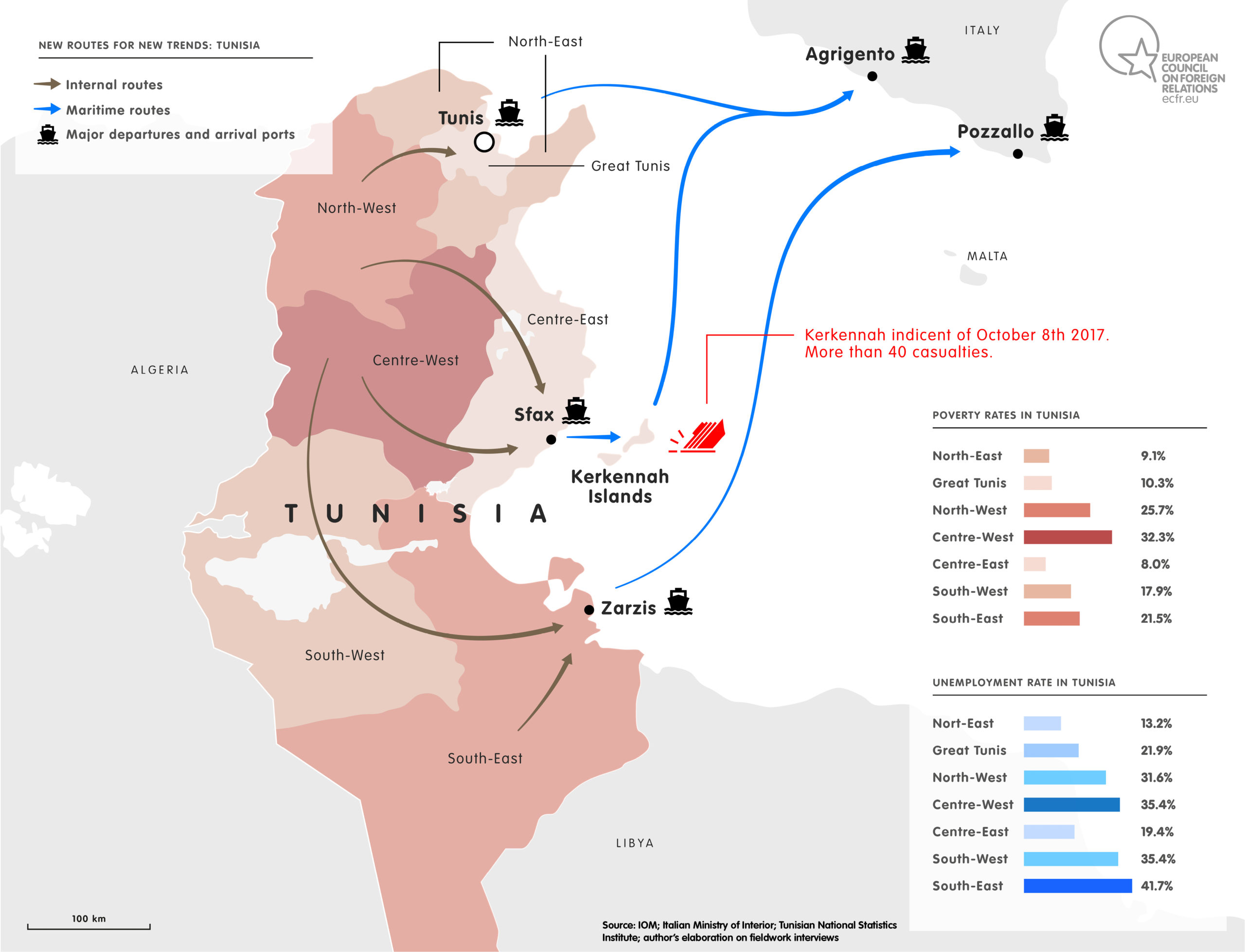

New routes and new crises: The case of Tunisia

Since 2017, as the number of migrants departing Libya has dropped, the number of people travelling from Tunisia to Italy has increased exponentially.

However, these trends are unrelated: almost all of these new migrants from Tunisia are Tunisians, while those who have travelled from Libya are predominantly sub-Saharan Africans. This suggests that Europe should tackle the drivers of migration in Tunisia independently, helping the country to overcome the difficult phase in which it finds itself. Although Tunisia’s process of democratisation is progressing, the country continues to have severe socioeconomic problems. The recent influx of migrants is just one of the most evident effects of this deteriorating situation. As such, the EU’s response to Tunisia will test whether it is able to regulate migration by providing prosperity in the region. To ensure stability and to prevent more people from leaving Africa, the EU needs a new approach – one based on local interests and aimed at tackling the specific needs within the local context.

“Fortress Europe”

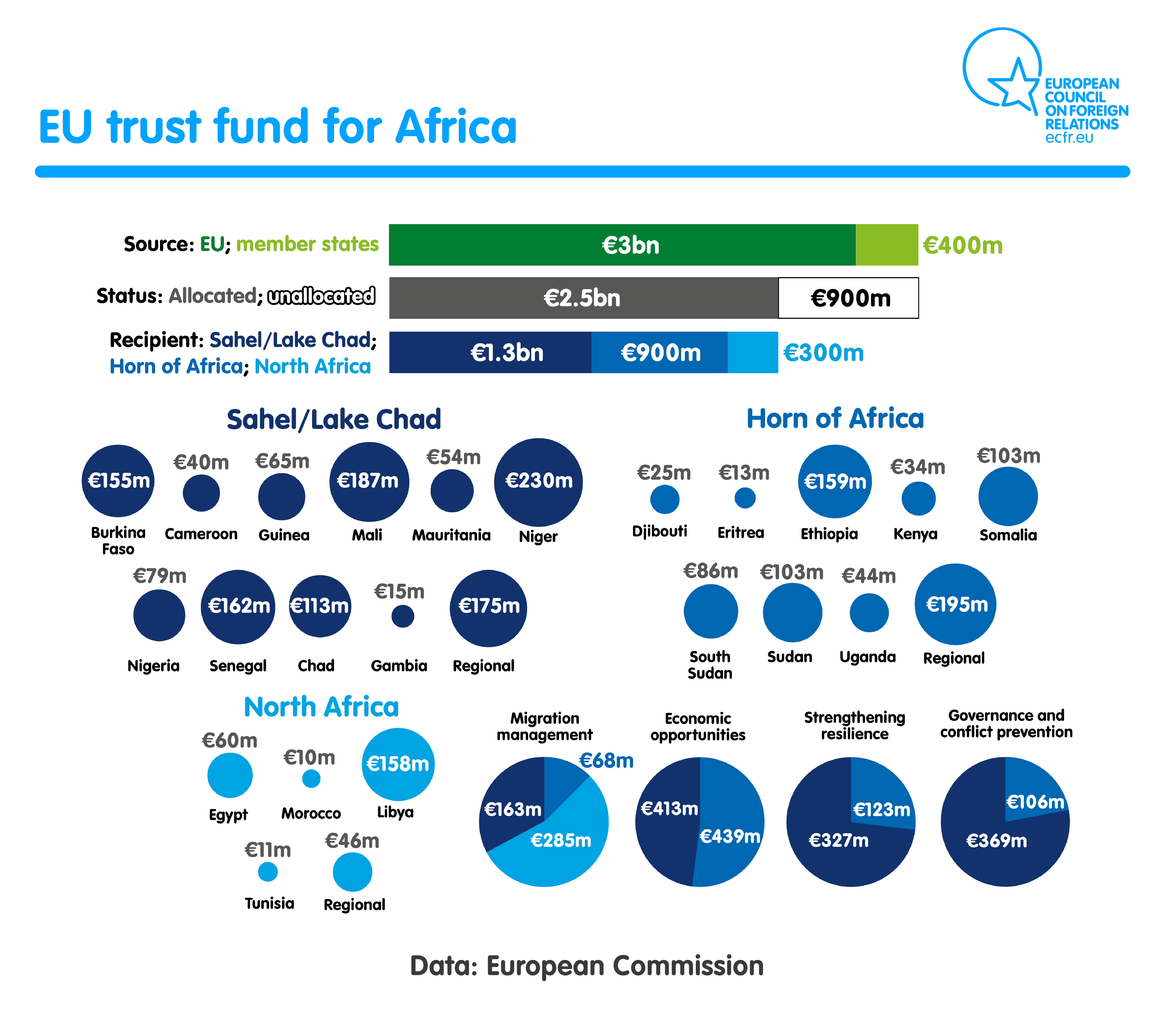

At the 2015 Valletta summit, the European Union created the EU Trust Fund for Africa, the initiative through which it aims to tackle the root causes of migration from Africa. Although the EU has recognised that Africa should be the heart of its efforts to address migration challenges, the policies it has implemented have done little to tackle the issue at the structural level. The Migration Partnership Framework – which prioritises work with Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Senegal – is part of no official EU policy and has produced few satisfactory results.

Brussels and member states appear to have often focused on their urgent interests in border control, security, and measures to restrict migratory flows rather issues within origin and transit countries. Moreover, their security-driven approach to migration risks exacerbating the problems that drive migration in countries of origin, generating greater instability in the long term. Through the policies it has adopted so far, the EU (which has a presence within civilian and military missions in Africa) effectively moved its borders south towards the Sahel. This externalisation of borders control and European security has helped to forge the image of a “fortress Europe” that has little interest in acknowledging or addressing the real causes of migration. Furthermore, reception and integration programmes within European countries are flawed. There is a lack of programmes that provide safe, legal entry routes for migrants and asylum seekers.

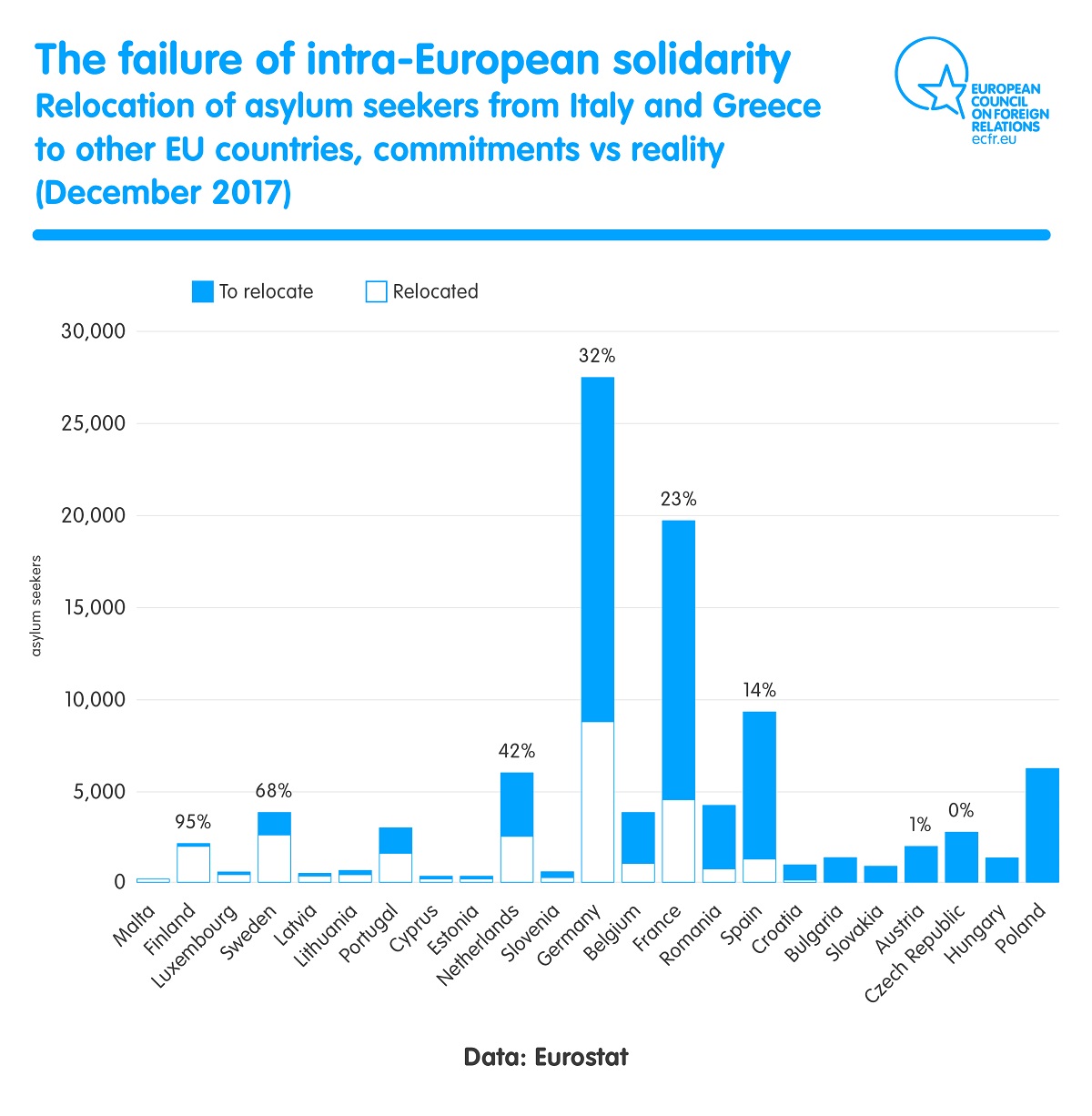

Moreover, proposals to establish the so-called hotposts in third countries are impractical for at least two reasons: the insecurity and lack of human, civil, and political rights in many of these countries; and member states’ unwillingness to relocate asylum seekers within their territories (as demonstrated by the failure of the relocation program launched in 2015, as well as UN High Commissioner for Refugees reports on asylum seekers who have been relocated from Libya to Niger).

Through the eyes of Europe: Perception versus reality

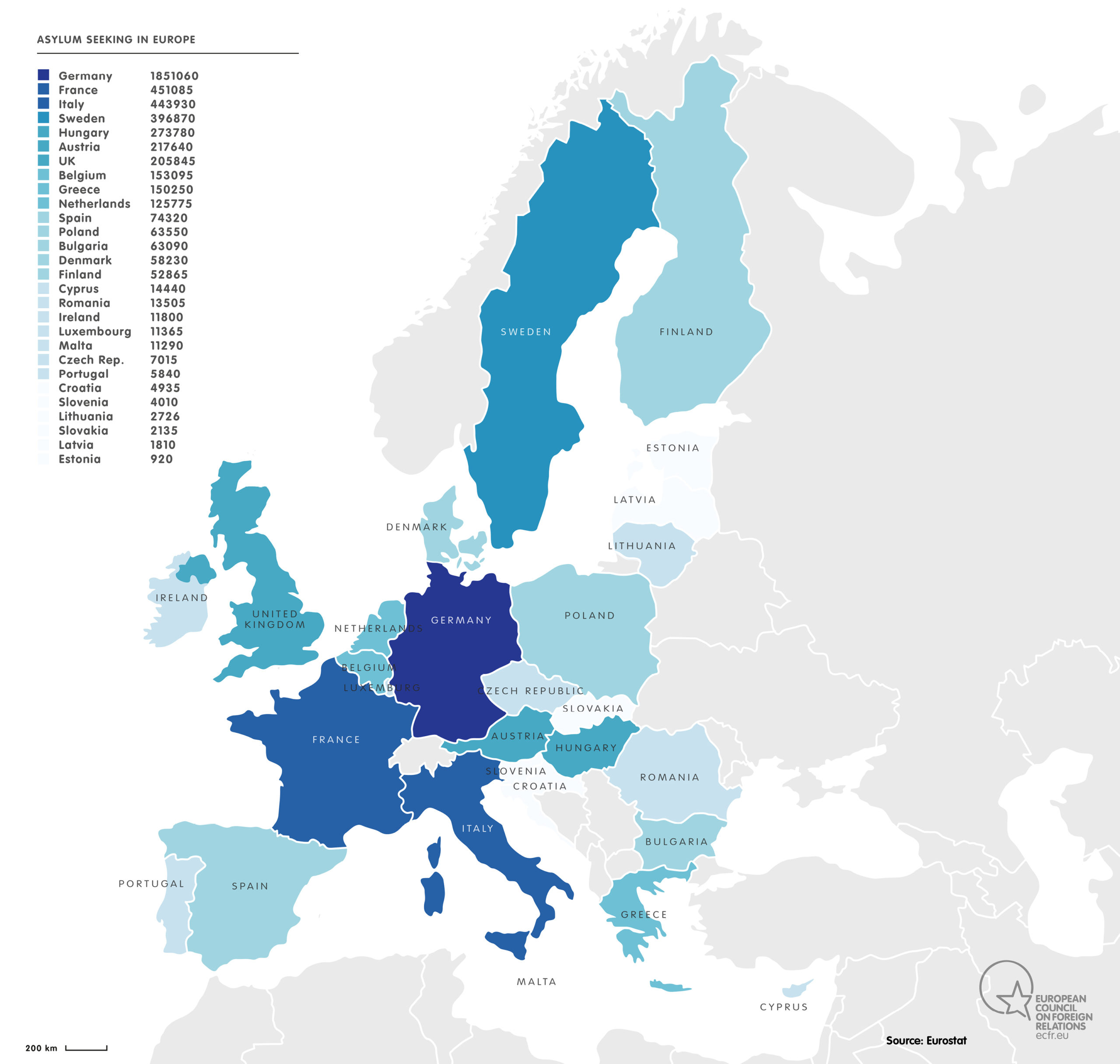

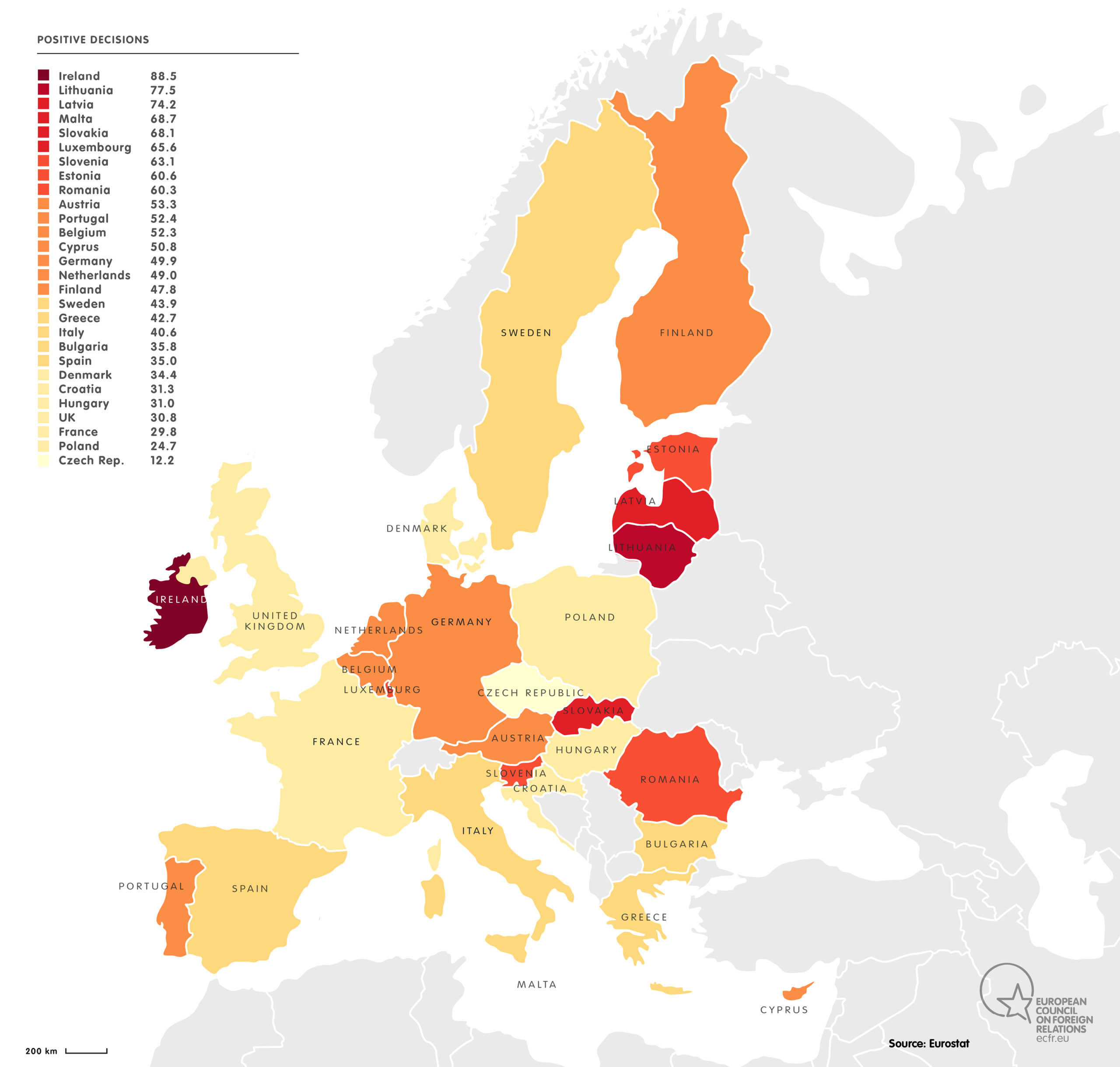

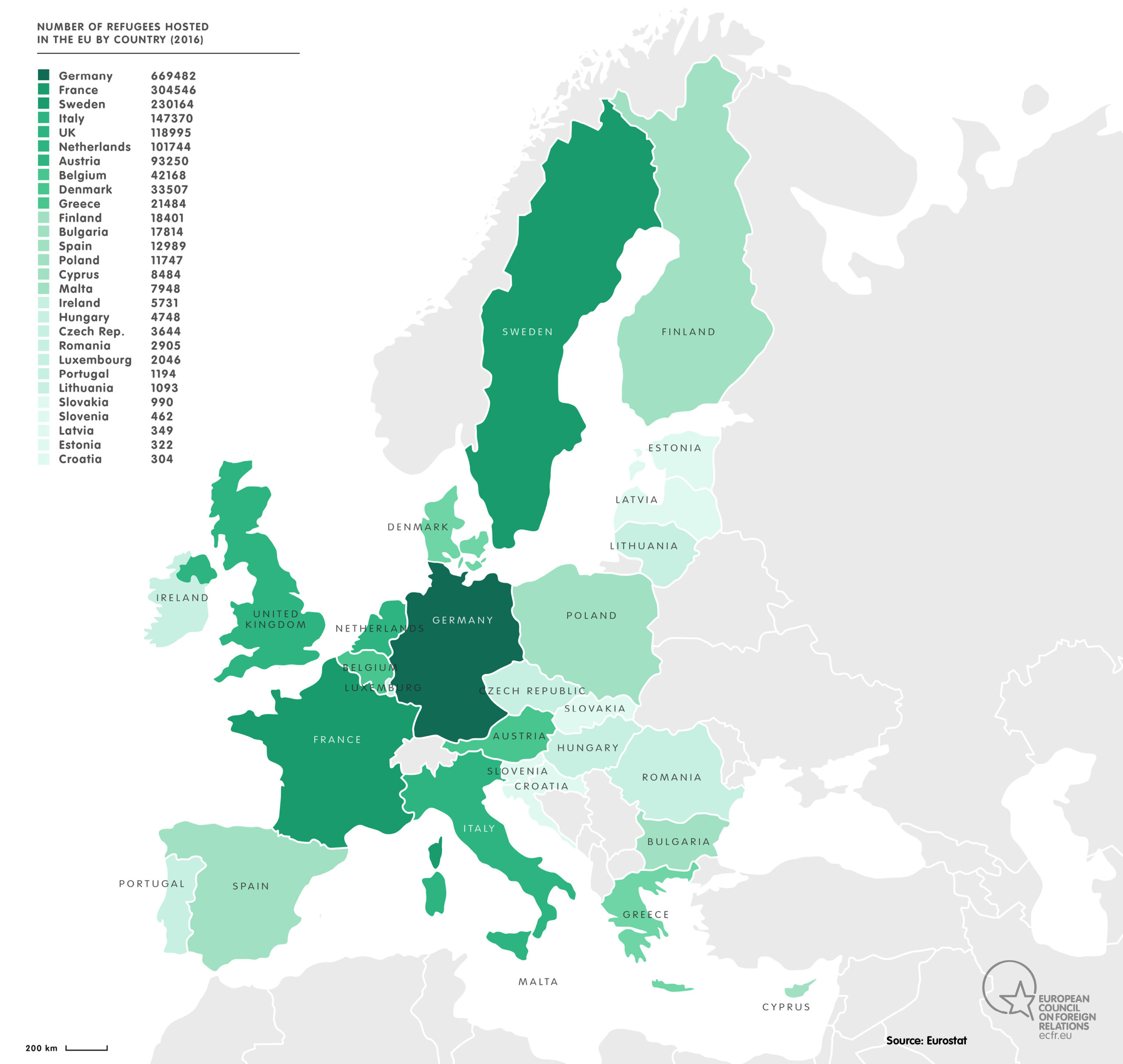

Despite widespread perceptions of Europe as having been invaded by migrants, the data show that European countries contain relatively small numbers of asylum seekers and refugees – although there is a clear imbalance in the distribution of asylum seekers across European Union. During the last six years, Germany has received more asylum applications than any other member state by far, while Italy and France have received the second- and third-largest numbers respectively.

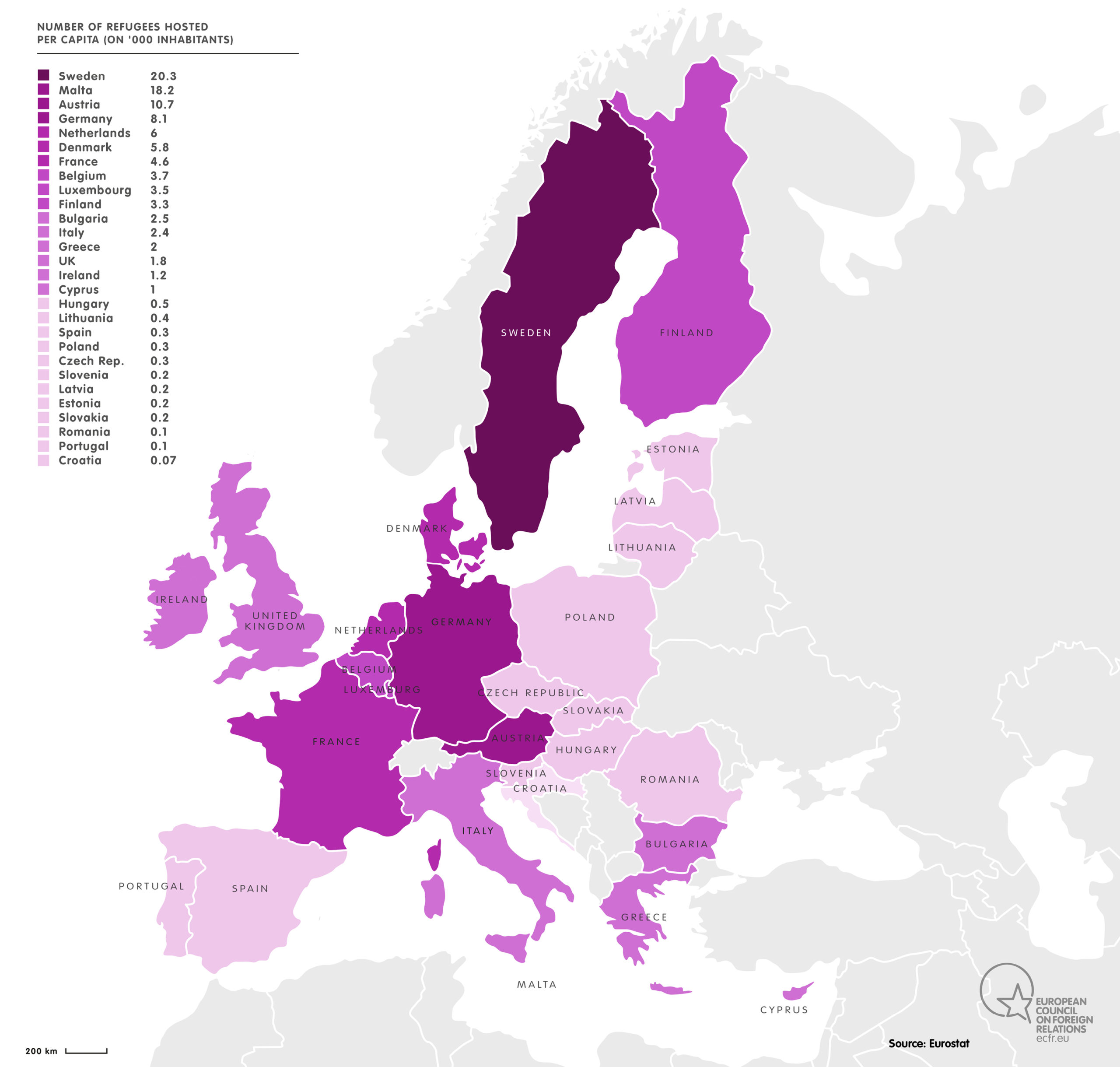

On average, around 40% of asylum applications are accepted through the recognition of refugee status, or humanitarian or subsidiary protection. Among member states, Germany hosts the largest number of refugees, while France, Sweden, and Italy host the second- third- and fourth-largest numbers respectively.

Although these factors may explain the rise of nationalist and eurosceptic parties in countries where elections have recently taken place, public perceptions of migration are often inaccurate. Indeed, Italy hosts ten times fewer refugees per capita than Sweden and Malta, and five times fewer than Austria. Furthermore, there is an imbalance in the distribution of asylum seekers between the northwestern countries and members of the Visegrád group.

The latters are among the main opponents of reception policies and of efforts to revise the Dublin regulation. The lack of a clear, shared EU policy is therefore the first obstacle to a long-term structural solution to the migration challenge in Europe. The sluggishness of asylum procedures is another obstacle. As there is no common asylum procedure in the EU, every member state adopts different standards. For example, the maximum duration of the regular procedure is eight days in the Netherlands, 33 days in Italy, and 180 days in countries such as Austria and France. A final decision on an asylum application takes an average of 24 months in Italy and Germany, and less than nine months in the Netherlands. A reform of the asylum system could help the countries most affected by migration speed their decision procedures, preventing them from becoming bogged down and unable to process new applications.

ECFR is grateful for the support of:

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.