Expanded ambitions, shrinking achievements: How China sees the global order

Summary

Xi Jinping took a bold stance at this year's Davos summit, claiming that China could be the leader and protector of global free trade. However, he fell short of pronouncing the same commitment to the international order.

While China finds little to criticise in globalisation, which has fuelled its rapid economic rise, it has an uneasy relationship with the international order, picking and choosing what parts of it to engage with.

China's governance model at home is fundamentally at odds with the liberal international order. Whether in climate talks, international arbitrations, or on the topic of open markets, China resists any parts of the order that infringe on its sovereignty.

Facing an increasingly interest-driven China, and a US in retreat from the international order, the EU must stand by its values if it wants to protect them. Faced with Donald Trump, Xi has sent a clear message about his country's commitment to internationalism. The EU should hold China to its word on this.

Policy recommendations

Stay true to the EU’s values

In the current political climate of eroding values and principles, there are two temptations that EU member states need to resist. The first is the temptation to move from the illusion that China has become “more like us” to a cynical strategy where Europe becomes “more like them” as a means of building bridges and cooperating. As tenuous as the EU’s moral high ground may be, it needs to preserve its values and those it has historically shared with the US. Washington should also be reminded of this.

Hold China to its word

In practical terms, this means that the EU should hold China to account on the recent pronouncements made by Xi Jinping and his government regarding multilateralism, the rule of law, free trade, the opening-up of the economy, and reciprocity. China must be challenged to push forward in those areas. After all, there is a strong rationale for conflict avoidance in China, and the country would be the biggest loser from a major setback to globalisation.

But don’t expect China to lead

The second temptation that must be resisted is to think that China could somehow replace the US as a dependable bastion of a free-trading and rules-based world order, let alone of democratic values. China’s political system affords opportunities for sectoral cooperation when it matches Chinese interest. But this fickle approach is simply incompatible with principled implementation of international law and global norms. This is even more true of the post-1989 ambitions for a global liberal order.

Maintain clear priorities

The appearance of Trump, and the more general questioning of globalisation by large sectors of Western societies, means that Europe has to adopt a Janus-faced approach, looking both east and west, to preserve its values. The US has become a priority as Europe attempts to feel out how it can bring back the Trump administration from isolationism. In doing so, Europe should be careful not to let China inadvertently off the hook through pre-occupation with the state of affairs in the US. Europe should take care to ensure its shift in priorities doesn’t make it blind to Chinese infractions. Two wrongs do not make a right.

Work to protect the liberal free trading system

Halfway between values and interests, Europe should also strive to maintain a liberal free trading system – something that still forms the heart of the European economic model. Today, it is at risk of being torn apart by different impulses of varying intensity. One is hostility to Chinese investment – a trend that is part of the so-called populist backlash against globalisation. The other is the US rejection of TPP and Trump’s economic pledge to put “America first”. Screening foreign direct investment on the grounds of preventing technology leaks, and on defence concerns, is not the same as shutting the door to China.

Act as one and know your strengths

There is a risk that recent moves by the EU and member states towards coordinated and demanding policies on trade and investment are scuttled by breakaway EU member states that seek to bilaterally woo Chinese investors. A recent American policy report is advising “fair reciprocity” with China in areas ranging from trade and investment to academic exchange and media.[18] These are exactly the sort of areas where the EU, acting as one, can make a difference. Member states that seek to opportunistically negotiate side deals with China are only undercutting themselves – allowing China to lobby the EU through them. The EU must remain committed to unified negotiation if it is to achieve the results it wants and protect its values on the global stage.

Introduction

President Xi Jinping’s keynote address at the World Economic Forum in Davos this year gave the world the strongest sense yet of how China wants to be seen in the global order.[1] In a rousing speech praising globalisation, multilateral institutions, the rules-based order, and even complete nuclear disarmament, Xi seemed to imply that China was willing to replace an increasingly isolationist United States as the champion of global free trade. The larger and unspoken question was whether China would also assume the mantle of leader and protector of the global order.

One might have been forgiven for thinking this was a speech delivered by an American president some 20 years ago, so much did it resonate with the words of Bill Clinton at the creation of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum. “We must remain committed,” Xi stated, “to developing global free trade and investment, promote trade and investment liberalisation and facilitation through opening-up and say[ing] no to protectionism […] We should adhere to multilateralism to uphold the authority and efficacy of multilateral institutions. We should honour promises and abide by rules. One should not select or bend rules as he sees fit.”[2]

The reason for this sudden change of tack for China does not come from within. External developments, chiefly the election of President Donald Trump, prompted the shift. Trump has not provided any assurances regarding free trade and the global order, preaching that “everything is negotiable” – a position that breaks with decades of Sino-American relations.[3] Xi’s speech betrays anxiety about Trump’s unpredictability, and a desire to persuade others that China can be a force of stability in uncertain times.

The election of Trump and the rise of populist and anti-globalisation forces in the West might signal a paradigm shift on the issue of China and the global order. Just two or three years ago, questions about the future of the global order centred on China’s potential contributions or challenges to it. Today, the world finds itself asking whether China could step in to lead, and what that would mean. China’s authoritarian governance system, sustained by a cocktail of ideological tenets, concerns for regime preservation, and an oft-cited legacy of Western encroachment, point to the same conclusion − a rich and strong China will not be a pushover. China has traditionally been a reactive force, framing its diplomatic efforts as responses to initiatives from the West. It would be a giant leap for China to step into the fray and evolve from reactive stakeholder to global leader.

Xi’s speech at Davos forcefully made the case that global trade brings global prosperity, and even pledged, in principle, further opening up of the Chinese economy. But there was less enthusiasm on the other aspects of the global order. The pledges Xi made towards the end of his speech all had to do with economic growth and development, rather than security and defence. If indeed the US appears to be wavering on some of its commitments as a leader and advocate of the global order, answers are urgently needed about China’s intentions. Is China adopting the global order, or at least adapting to it? Or is it, on the contrary, a rising revisionist power seeking to skew the tenets of the global order in its favour? Most fundamentally, will China make proactive contributions, or even take the lead in supporting a new or modified global order?

There is no simple answer. China takes a very different perspective on globalisation and free trade –which by and large it benefits from − and on the global order, which at best it seeks to adapt and at worst to supersede. But the most important component of China’s attitude to both the global order and globalisation is that it analyses them piecemeal. China breaks the tenets of both into separate components – those it accepts and those it rejects. A global order with Chinese characteristics is one that does not require large Chinese concessions. It is one that does not threaten China’s insecure regime by promoting liberal values at home. And it is one that focuses on self-interested guarantees for free trade and uses international law to protect Chinese sovereignty (and in theory that of other nations), with a distinction between the relative importance of “big” and “small” states. China’s preferred global order, just like its preferred version of globalisation, is both low cost and illiberal.

How should the European Union react to the changing roles of the US and China in the global order? To its west, the US eagle seems intent on reducing its commitments to the global order, while to its east, a rising Chinese dragon takes a mercantilist view of it. Since the very beginning the EU has been a normative power, capable of bringing other nations in line with its way of thinking through the establishment of global norms. As our societies face their own populist backlashes, Europe needs to consider whether it can rely on China to protect those norms. Understanding how China will react to, and interact with, the global order in the coming years is therefore key to understanding how the EU can protect its own values.

This paper seeks to understand how China balances the benefits it gains from globalisation with the maintenance of a stable global order. It focuses on explaining China’s attitudes towards specific parts of the global order to help European policymakers interpret China’s actions.

Globalisation versus the global order

The challenges confronted by the global order today are very different from those faced after the second World war. Then, the global order faced both Soviet interference and insurgencies in developing nations. At the same time, neither side in the cold war projected influence through globalisation, which only came about in the 1980s. Consequently, there was less interdependence between states than today. Furthermore, there were numerous stand-offs or hot wars that involved persistent military confrontations or actual land combat by proxy between the world’s superpowers. The end of the cold war gave birth to the hope of a global order that not only was toothless, but really needed no teeth. The trend towards the disarmament of most advanced industrial societies in the post-1989 period testifies to this hope.

Today, new challenges have risen from within the societies of the nations that prevailed in the cold war. In the post-cold war period, these democracies sought to create a perfect, individualist, and “value driven but belief-free” utopia. Now we are experiencing a backlash, launched by those who long for lost identities and solidarities.

The liberal world order, understood as the combination of democracy, free markets, and the rule of law in international relations, now faces two fundamental challenges. One, largely stemming from within the developed West, is a rejection of liberalism due to discontent with globalisation. The other is the willingness of some nations to test, or even face down, democracies. Coalitions of “anti-system” nations are emerging. These nations may not share specific interests, but they do share the same general reservations about the global order. Now they are pooling their capacity to disrupt the liberal order.

Modern history shows that such challenges come in cycles. While the dominant narrative of the democratic revolutions of the eighteenth century is one of steady victories towards “progress”, there have been several periods of historical regression. Edmund Burke, for example, documented the re-imposition of liberal conservatism across Europe against progressivism, while Oswald Spengler prophesied the decline of the West after the catastrophic first world war, and Karl Polanyi described in 1941 how the liberal order had unravelled. Domestically, déclinisme – the deep-seated fear of societal regression and nostalgia for the past – recurs in cycles. It is no accident that the United Kingdom, the United States, and France, where democratic revolutions originated, are today the centre of large-scale movements that seek to reverse course and restore national identity over international values.

Many Chinese intellectuals are themselves experts on the rise and fall of nations and societies – because this is the preferred script of Chinese history. The internal decline of the West makes sense to China, which faced a similar decline beginning in the late eighteenth century. China has a pessimistic outlook on the global order, which it justifies by referring back to the onslaught it faced from the West during the Opium Wars. But this pessimistic philosophy also reflects China’s self-awareness of its own internal decay in the same era. In China’s preferred historical narrative, its 150 years of victimisation at the hands of the West extend into the present. Even demonstrations of Chinese strength today are depicted as historical justice for past suffering. Exceptions are few, and confined to international economic relations, where China’s rise cannot be denied, even by China itself.

China’s outlook on the global order can be tied back to a book that probably had more influence than any other on Chinese intellectual trends − Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and its central idea of “survival of the fittest”. The idea remains popular in mainstream Chinese society today. Even the “progressivism” of China’s anti-imperialist May Fourth Movement and its utopian belief in modernity − or its parody under Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution − were founded on the basis of overturning existing values for survival. In order to save China, one first had to burn it down. China’s philosophy, taking into account its own experience, is neither zero sum nor win-win; it is winner takes all, loser loses all.

China’s rise and vision

China’s rise in the last 40 years has been momentous, owing to its integration in global markets. As the benefits China reaps from globalisation have increased, so have others’ expectations of its responsibilities for preserving the international order. The Chinese have not always welcomed this attention. For China, the changes to the world order, cemented at the end of the cold war era, can be summed up in a Chinese-sounding four-word maxim: expanded ambitions, shrinking achievements.

In the last 40 years, China has emerged as an enthusiastic supporter of globalisation while public opinion in the West has soured on it considerably. In the 1990s, Western powers assumed that the formula of integration through free trade would bring a convergence of norms and values on the way to economic growth. But as its share of the global economy has increased, China has increasingly been faulted for breaking away − whether surreptitiously or openly − from international norms that it has agreed to uphold.

China has strict and mercantilist ideas about what values it imports. Although it believes that “connectivity” serves to protect against conflict, its vision of globalisation pulls in two separate directions. From an economic standpoint, China advocates to others the most open position possible, while maintaining its perks as a “developing” economy under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. However, from a social and cultural standpoint, China is much less open. While China is liberal on trade, it is quite the opposite at home − controlling all online information and all social communication, whether public or private. This increasingly polarised vision is becoming more deeply embedded under Xi Jinping.

China is much more apprehensive of the global order than the democracies around the world commonly understand. The Euro-American belief in the value of a global order has grown since the end of the cold war. And since then, Western nations have promoted an increasingly ambitious and extensive agenda for international cooperation.

China is not always happy with how ambitious the global order has become even as it depends on that order. China has deep and unacknowledged interests in maintaining a stable order because of its integration in the global economy. A disruption to that order would − by necessity − be a disruption to its own economic interests. This vulnerability dictates how China positions itself as part of the global order and is the main deciding factor in finding compromises between riding the wave of globalisation and resisting the advances of a global order that seeks to impose liberal norms.

Where China “sets the needle” between reaping the benefits of globalisation and pushing back against the global order has now come to dominate its political thinking. Its approach to the international order is one of cautious engagement. In the words of one Chinese expert, it “picks and chooses” when to engage with the international order, and only then after weighing up the costs and benefits of doing so. In many ways, China attempts to dampen the impact of the global order by weakening UN resolutions or sitting on the fence. Still, dampening the impact of resolutions is not the same as sabotaging them.

China characterises most of its international actions as reactive rather than proactive. But China’s underhanded description of its own international role has fed the opposite narrative in the West – one that ranges from Chinese assertiveness to a China that will soon rule the world. Indeed, “Chinese supremacists” can envision a future of global leadership by China, though few envision that its leadership would be proactive. It would more likely be leadership by default in core areas of Chinese interest, such as international trade, or through its ability to act as a spoiler. This shouldn’t be surprising. China has always had a much less demanding vision for the international order than the West. China may rule the world one day, but only if the West has lost the capacity or the will to.

Today the challenge is of a China that becomes increasingly reactionary. As the party-state enforces nationalism and gathers hard power, it is loath to engage with a global order that seeks to impose norms infringing on its domestic regime. Instead it prefers to deal with a minimalist and low-cost international order that leaves more leeway for nation states to conduct themselves as they please. China suggests that nation states should work to roll back an intrusive, over-ambitious global order, and push against the rising demand in the West for guaranteed individual rights. How Europe and the West react to this attitude is of considerable importance to the protection of its own values.

The backlash against globalisation

The idea that the balance of power has changed because of the rise of peripheral challengers, such as Turkey, Russia, and China, is an illusion. These countries were not responsible for driving forward economic globalisation, nor are they responsible for the resulting economic shift towards emerging countries in the former “periphery”. Rather, it is the centre – the industrialised West and Japan – that has driven these changes. Financial liberalisation and the rise in foreign direct investment changed the global economic map from the early 1980s. Suddenly, it was cheaper to import from China and other developing economies than to produce in Europe. European industry began to dry up.

The “China angst” created by globalisation is distinct from Europe’s fears about labour or refugee migration. Angst over China comes from job losses in the West caused by the decline of native industry. In the United States, there is now a documented perception of higher numbers of job losses since 2001 – the year when China entered the WTO.[4] In Europe, too, that perception is rising, although it remains at a lower level than the hostility to immigrants and unfair labour market competition targeting other Europeans and immediate neighbours.

The list of countries that maintain a trade surplus with China has become much shorter since energy and raw material prices dropped in 2011–2014. South Korea is among the few remaining surplus exporters to China, but even Japan has been running a trade deficit. The problem isn’t just that China has benefited so much, it’s that it has done so little to support others’ advocacy of free trade that the pendulum has now swung the other way. More now see the downside of China’s outwards economic expansion than the benefits.

Many saw China joining the WTO in 2001 as the beginning of an even deeper process of opening up its economy. In retrospect, it is clear that China understood its WTO admission terms as the upper limit of concessions it was willing to make. Not even the extraordinary growth of its exports and trade surplus in the following decades would persuade it to desist from taking a principled stand: China is a developing economy, allowed many exceptions to market competition regulations. All the same, it refuses to adopt a principle of reciprocity or symmetry in its trade and investment policies. On the contrary, China’s ambition to regain a large share of its booming domestic market has led it to favour Chinese companies over their foreign competitors. Chinese state-owned enterprises are being built up again, with 15 new mergers since 2012 and privileged access to financing, at home and abroad.[5]

Even with a lower amount of foreign trade in 2016, China runs very large trade and current account surpluses, and is a significant capital exporter. It doesn’t need to accommodate foreign interests in China because it receives enough benefit from its own trade with other nations. In many ways, China can afford to operate an asymmetric economic policy. The only thing it loses in the process is the goodwill of its partners in developed economies. As long as the same terms endure, China finds very little to criticise about globalisation, even as Western public consensus on the benefits of Chinese trade erodes.

China’s uneasy relationship with the global order

China may be content with globalisation, but it has plenty of complaints about the global order. This is, not least, because China believes that the order is biased in favour of its Western founders, and because its own ambitions have vastly expanded since it originally joined the UN and other multilateral organisations. China is often reticent to accept the global projection of Western norms, which it sees not only as a threat to its own political model, but also as inefficient compared to it. China is hostile to the key trend within the West: the retreat of the state in favour of civil society and non-governmental, often grassroots, organisations, as well as the rise of both individualist and communitarian demands at the expense of civic commitment. This makes the common ground for shared values very small indeed.

As different as they may be, Chinese and Western views are not perfectly opposed. Western societies are themselves deeply divided over the respective status of the state and civil society, and the Chinese pingmin – ordinary citizens – are among the most ardent individualists on earth. Yet their individualism takes the form of passive resistance rather than direct challenge to the state. In fact, their individualism often coexists with support, in principle, for a strong state.

Above all, it is the benefits of globalisation that draw Chinese citizens to global values. But the calculus on which China has based its growth, and its assumptions that gains from globalisation are irreversible, leave it in a potentially perilous situation. If China’s partners sour on globalisation and begin to retreat from free trade, Chinese public opinion could be driven further into active nationalism. This portends increased volatility for all, including the European Union.

China has been a free-rider on trade liberalisation and globalisation, with low levels of voluntary contributions to multilateral efforts. At the same time, it has demonstrated its willingness to break international legal norms by contesting territory in its own region. The status quo is far from ideal for China’s partners – and, as a result, there are rising demands in the West for greater reciprocity, or at least regulation to temper the advantages China enjoys at the expense of industry in the West. This may drive Chinese public sentiment further away from supporting global values. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), seeking new sources of legitimacy, may find its nationalist drive supported by a society that can no longer see the benefits of globalisation so clearly.

Picking and choosing within the global order

China’s modus operandi in the global order is to pick and choose what it engages with and what it doesn’t. Despite resisting some international norms, its cooperation with multilateral organisations has actually increased in recent years. As China’s economic integration has intensified, so has its integration into the global order. China is a keen supporter, in principle, of the UN system. In one official’s own words: “China supports the current international order. And you may take note that the word used is ‘international order’.”[6] The Chinese seldom talk about the “global order” because of the assumptions inherent in the phrase.

Today, China is the second-largest contributor to the UN’s general budget, and to the Department of Peacekeeping Operations’ budget. But these are statutory obligations handed down by the UN. More significant – if it is implemented – is the pledge by Xi Jinping to contribute $1 billion to the UN Peace and Development Trust Fund for reconstruction and stabilisation efforts. However, on the whole, China has been miserly with humanitarian efforts. In 2016, it was ranked as the 39th greatest contributor to the UNHCR, the UN’s refugee organisation, donating a paltry $2.8 million. For comparison, contributions by the EU and member states or individuals amounted to $1.2 billion in 2016.[7]

Nonetheless, China continues to interpret the international system restrictively. China also tends to resist the extension of mandates and mission creep – something that has been a key feature of post-1989 multilateralism. The section below analyses China’s choices, its negotiating positions, and its red lines, to better understand how China interacts with the global order.

The issue of representation

One of China’s perennial complaints is that it is under-represented on the world stage. On this issue, however, China differentiates between the UN and all other institutions – even though it was excluded from the UN until 1971, when it replaced Taiwan at the UN. Being vocally supportive of the UN allows China to shift emphasis away from the US-led security architecture and towards a multilateral format where it has more influence. At the UN, China believes it has a position that befits its stature. It is busy denying its closest neighbours a permanent seat at the Security Council. It is indeed able to use its veto to block permanent membership for Japan − which it does vehemently − and for India − which it does less obtrusively, but just as effectively.

China is less happy about the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Even though the IMF is a specialised agency under the UN, it has its own separate legal status and autonomy. In particular, it is the only UN-affiliated institution where voting quotas apply, instead of a “one country, one vote” system. China’s main sticking point with regards to the IMF has been the issue of voting quotas, which the US holds a monopoly on. Although the US Congress finally approved new quotas in December 2015 that give China (and other emerging economies) a bigger share, the US share still affords it a veto right over IMF decisions. Partly in response to the constraints it faces at the IMF, China created its own international financial institution in 2015 − the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Launched at the peak of China’s financial power, it has attracted almost all of America’s partners with the exception of Japan. Ironically, China has taken a leaf from the US’s book and retains a practical veto over AIIB decisions through its large voting share among the 57 founding members.

It was clear, in the past, that China had reason to complain about under-representation, but today China holds key positions in the IMF. Recently it held the deputy managing-director and chief economist posts at the IMF. It has also held the post of director-general at the World Health Organization since 2006. China holds the post of under-secretary-general at the Department of Economic and Social Affairs at the UN, which helps to fulfil its ambition to stay close to the G7 countries, and, more ominously, a former Chinese vice-minister of public security has headed Interpol since November 2016.

One has to distinguish between the UN and associated organisations, and global financial institutions, especially the IMF, when it comes to China’s complaints about representation. At the UN, China is able to attain votes from other states by campaigning actively for important resolutions, and has even campaigned for its seat in some instances – most recently for the Human Rights Council. It lobbies discreetly for executive positions – for instance, in 2016, it is said to have campaigned for the post of director of the Department for Peacekeeping Operations, although it was unsuccessful.

In sum, the issue of representation for China is diminishing in importance and it is harder for Beijing to justify its complaints when it does so well for itself. China is well represented in international institutions, but its funding of UN agencies and special programmes does not correspond to the influence it wields from senior positions within the organisation.

Foreign intervention and use of sanctions

China’s position on foreign interventions involves balancing domestic principles with a mercantilist logic inspired by its economic interests and fear of subversion. Does the affirmation of national sovereignty against international intervention, whatever the cause, qualify as a challenge to the international order? Certainly not in a traditional sense. It is the increase in interventions post-1989 that has alienated China from the attempt at a new and more liberal world order.

In 1955, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai signed up to the five principles of pacific coexistence at the Bandung Conference. Non-interference and sovereignty figured prominently in the discussions between them. But a decade ago, China began to soften its stance and accept interventions into domestic conflicts if they descended into genocide or could not be contained by international borders. It began balancing its general preference for Article 2 of the UN Charter – guaranteeing sovereignty − with a limited acceptance of Articles 42 and 51, which allow for intervention.

But China’s acceptance of interventions was relatively short-lived. Since the 2011 Libya intervention, which China claims went against the original goal of protecting civilians, it has become much less accepting of foreign interventions.[8] Its opposition to any UN-mandated military intervention in the Syrian civil war is a practical demonstration of the limitations China places on the UN’s role. The decision by major powers not to intervene in Syria has resulted in an enlarged civil war, a regional conflict, and a humanitarian tragedy. And finally, a Russian military intervention has served to bolster one side at the expense of the other. Yet China has not entirely turned its back on the post-1945 international order in this respect. Its stand on the Syrian crisis is overtly based on the doctrine of national sovereignty and non-interference as applied to the Assad regime. Its philosophy of sovereignty, more than any actual stance on Middle East issues, informs its position.

China has picked its battles carefully on the issue of international intervention, often preferring to extract concessions about their extent than to oppose them. In two celebrated instances – Iraq in 2002 and Libya in 2011 – it avoided a veto clash at the UN Security Council by compromising its own principles in the interest of protecting its relationship with the United States. Nonetheless, in almost any crisis, China couples its vote with admonitions for “patience” and “negotiation”. In 1999, China was more vocal against NATO’s Yugoslavia offensive specifically because there was no effort to achieve a UN mandate – and therefore no compromise to be made. In 2015–2016, China diminished the severity of its sanctions against North Korea instead of opting for frontal opposition. In fact, leaked information from a UN report indicate that China kept in place a network of North Korean ‘front’ companies that have allowed North Korea to dodge sanctions and trade across the border. In 2016, China also breached the limit of coal trade agreed with the UN sanctions committee, buying twice as much as it had agreed to.[9]

Abstention in the UN Security Council, which has traditionally been a useful resource for China, is also declining. China now abstains on only 2 percent of UN resolutions. This implies a departure from its previous policy of non-involvement and indicates that the China of today seeks a more active role in shaping resolutions. China has also supported 170 out of 178 votes for sanctions, vetoing three on Syria in 2010 and 2011 and one on Zimbabwe in 2008. But this optimistic view of China has its limits. By bargaining hard on resolutions, China has also watered many of them down − the key exception being resolutions on terrorism where it usually endorses the strongest positions. There are also large question marks around whether China has implemented key sanctions agreements on Iran and North Korea.

Since 2004, China has become very active inside UN peacekeeping operations. China now participates in nine operations, including in Lebanon, Mali, and South Sudan, deploying combat troops in the last two instances. In the case of Mali, Chinese direct involvement against terrorism and the study of military practice in desert areas is useful to China, since the terrain is very similar to the rolling plateaus and deserts of Western China. In South Sudan, China has oil interests that are directly threatened by the rising civil war, leading some to conclude that it is using UN peacekeeping troops to guarantee the safety of its own investments. Since 1989, China has sustained 18 casualties from UN-deployed contingents. In his September 2015 UN speech, Xi pledged $100 million to the UN emergency response force, and announced the creation of an 8,000-strong “standby” reserve for peacekeeping.[10] So far, the emphasis is on the word “standby”.

Law of the Sea and the arbitration process

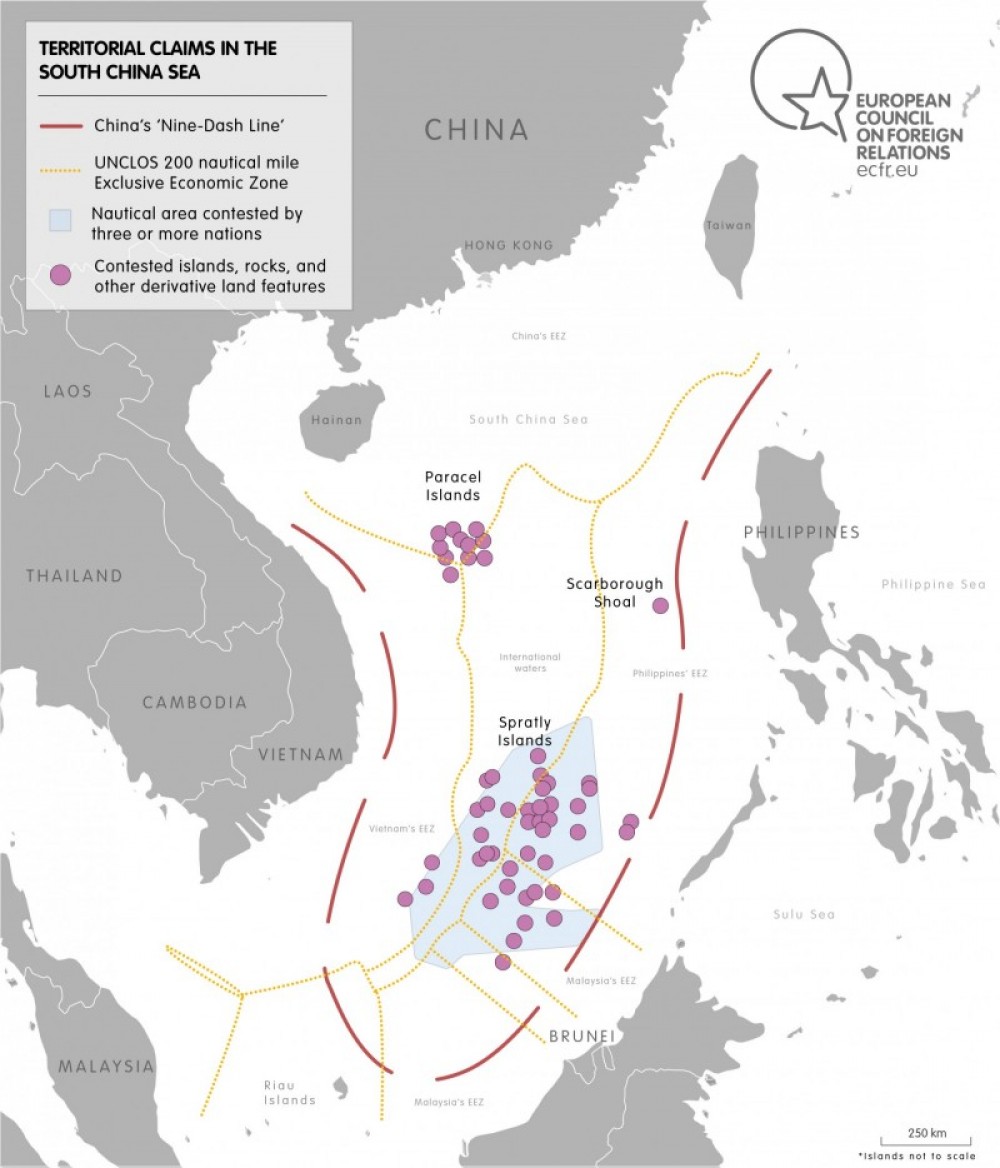

China crosses the line between traditional criticism of the international order and flat-out rejection of it when one considers its regional disputes and the implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). China signed and ratified UNCLOS in 1996, but with a reservation on the arbitration of border disputes and military activities.[11] China continues to cite its preference for negotiation rather than arbitration over international boundaries in the South China Sea (even though decades of negotiation have remained fruitless). But it is not alone in its reservations on UNCLOS and is responsible for only two of the 123 reservations made by signatories.

What separates China from others is its interpretation of the law, specifically the articles on freedom of navigation. Instead of allowing ships to exercise their right to innocent passage through territorial waters, China requires that all ships declare their presence when they enter its waters. It also requires similar supervision of its Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and the adjoining airspace that it claims. But these objections are not new either. China has long put forward these views, but now it has the will and capacity to act upon them. Complicating the issue further is China’s ambiguity over the set of rules it follows. In other countries’ territorial waters, China adopts the prevailing interpretation of UNCLOS, rather than the one it claims in its own waters.

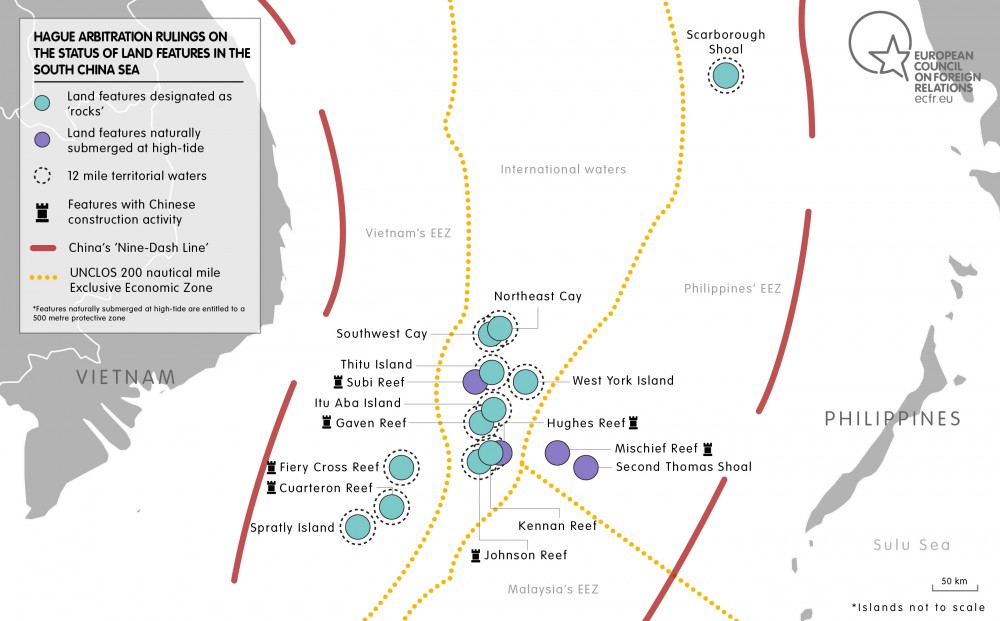

The situation created by the July 2016 ruling from The Hague on the South China Sea (SCS) has made waves. The arbitration tribunal ruled that there was no legal basis for China’s claims to EEZs over land masses and some territorial waters in the SCS. The tribunal also stripped the legitimacy of China’s claims to land it has created through land reclamation initiatives and construction. The tribunal itself did not rule directly on the sovereignty of individual features, but about whether such land features – atolls, rocks, and islets, whether submerged or above sea level − can generate sovereignty rights on their own account, and therefore also over adjacent maritime space. The court ruled that they cannot. In line with its reservations over arbitration, China stated that it would ignore the court’s ruling. China’s reservations to UNCLOS concerned sovereignty claims and international boundaries, rather than the criteria that must be fulfilled for land features to attract rights. This means there is still some room for regional contenders to negotiate sovereignty among themselves.

In its section on “habitability and economic life”, the court ruled that to justify an EEZ, a territory must, in its natural condition, be able to sustain “a stable community of people for whom the feature constitutes a home” and economic activity that doesn’t rely on external resources or is “purely extractive in nature”.[12] By denying maritime entitlements to many land features in the SCS, the tribunal drastically reduced the legal basis for China’s claims of sovereignty – particularly its Nine-Dash Line, which very roughly sketches out the extent of these claims. The tribunal also directly validated the Philippines’ EEZ claim of 200 nautical miles from its established baseline, in accordance with UNCLOS norms.

Worldwide, the ruling was a very welcome development. UNCLOS III had unwittingly created a global race for extended claims on maritime areas − be they EEZs or extended continental shelves − through its lack of clarity. The shaky basis for basing territorial claims on minor land features – sometimes just rocks barely emerging above sea level – has created an entirely new category of maritime disputes. In effect, the arbitration award rolls back many of the possibilities for claiming such territories, creating firm requirements on which to base EEZ claims. China has refused to acknowledge the validity of the arbitration process, but has stopped short of withdrawing from UNCLOS. China therefore continues to be bound by the arbitration award, despite the reservations it made upon ratifying UNCLOS.

But China’s method of fighting the court’s arbitration judgement has left some scratching their heads. In the wake of the arbitration judgement, China has taken the issue to its own Supreme People’s Court, which, unsurprisingly, has ruled that the land features within its Nine-Dash Line are fully sovereign Chinese territory. China’s decision to take this issue to its Supreme People’s Court reveals its philosophy that national sovereignty supersedes international law. The only things bolstering China’s claims now are its own court ruling, and its own historical criteria for its territories, which predate the creation of UNCLOS.

It was the Philippines that originally brought the case to the International Court of Justice. But shortly after coming to power, newly elected president Rodrigo Duterte, who is openly sceptical of America’s security guarantees in the region, engaged in a goodwill initiative towards Beijing, dismissing the policies of his predecessor. The goodwill gesture has been reciprocated by China, which has led it to resume its economic projects in the Philippines. It has also declared one of the contested areas − Scarborough Shoal − a wildlife reserve, with the announcement that both Chinese and Filipino fishermen are banned from operating on or near the atoll. While all of this sounds promising on paper, China has fallen short of making any legal commitment to this effect. As such, the agreement on the use of waters around the contested atoll remains informal and can easily be rescinded in future.

China’s attitude to maritime issues and international law reveals much about its intentions towards the global order. In China’s view, no tenets of international law can ever trump its national sovereignty or jurisdiction if they are deemed contrary to China’s core interests − and, with some hesitation, China has increasingly treated the South China Sea as a core interest. China’s adherence to UNCLOS embodies its “pick and choose” philosophy on international rules. China ratified UNCLOS but exempted itself from arbitration on issues such as border disputes and military passage. Finding that the tribunal result did not lean in its favour, it has decided to go by its own facts on the ground and will play on the reluctance of other parties to engage in conflict to strong-arm them into getting its way.

It is hard to see how China could be a guarantor of the legal order when it disregards, outright, some of its provisions in its own neighbourhood. But one should also be aware of weaknesses that UNCLOS III has revealed. Establishing a fuzzy delimitation for huge maritime spaces, with large economic and security implications, has created new possibilities for conflict; and allowing states to register reservations that, in effect, undermine the enforcement of the convention, was self-defeating. The beauty of the arbitration system is that it has found a way to legally address some of the loopholes in UNCLOS III. But it may have come too late in the day.

Climate change cooperation

If the response to the South China Sea disputes showed China at its most difficult, environmental policy and climate change mitigation have been highlighted as an area of possible Chinese cooperation – at least in the media. China’s environmental degradation and the increase in its carbon dioxide emissions currently make it the biggest environmental risk to the planet. But China has put significant resources into renewable energy and its targets for decreases in coal production pre-date the groundswell of international action on climate change – even if it has failed to hit them.

China has maintained an active hand in diplomatic initiatives on climate change, although it has at times been accused of being a spoiler, especially following its opposition to any agreement at the Copenhagen climate conference (COP15) in 2009.[13] After China impeded the process in 2009, the Obama administration and French organisers managed to win Chinese buy-in in 2015 at COP21 in Paris. Finally, all parties agreed to develop a target to cut carbon emissions. Today, in view of declarations by incoming president Donald Trump against the Paris agreement, China has been held up, by some, as the new global leader on climate change mitigation.[14]

But arriving at such a conclusion would be foolish and short-sighted. COP15 was sunk by a spat between the Obama administration and the Chinese government. The US, quite late in the day, decided it wanted to include a verification process in the agreement that would necessarily rely on international monitoring of domestic emissions. But this was one step too far for China, which saw this as an infringement on its sovereignty.

The Obama administration took a different approach in the lead-up to COP21. In view of its bitter relationship with China on several grounds – the Libya intervention, the South China Sea disputes, the Senkaku/Diaoyu island dispute, and dealings with North Korea – the US needed to get results in at least one important area to justify what remained a nominal engagement policy with China. Equally, China wanted the option of non-binding cooperation and to avoid being criticised as it had been after COP15 in 2009. Two side-by-side declarations by Presidents Barack Obama and Xi Jinping were therefore prepared, with separate and sufficiently distant targets set for a cap on carbon emissions to be achieved by 2030. Steps for verifying implementation of the agreement were removed in what ended up as two separate political commitments rather than a legal agreement of any sort.

By falling short of a legally binding agreement, the US and China ended up setting a ceiling for progress on future carbon emissions through COP21, and they weakened the prospect of real progress on climate change mitigation. Other participants in the talks knew that steps towards climate change mitigation would not be legally binding for either China or the US, so there would be no penalties if they failed to reach the targets themselves. The COP21 agreement of December 2015 was a brave attempt at securing commitments and pledges towards reducing carbon emissions, but one that ultimately lacked legal substance. The nearest thing to a legal verification process was the pledge for early review of progress towards the agreed emissions targets.

China initially implemented some emission-capping measures, but despite its investment in hydropower, solar panels, windmills, and nuclear plants, it has remained the world’s greatest exporter of coal-fired thermal plants. India, for instance, will buy one coal-fired thermal plant from China every three weeks for the next five years. Moreover, in early 2016, the downturn in China’s core industries such as steel or construction threatened GDP performance and employment. This caused the government to reverse course on emissions. A planned decline in coal production in 2016 was almost matched by an equivalent increase in coal imports, and use, contributing to widespread particle smog.

To the credit of the US, the Obama administration did pass verifiable emission-reduction targets into domestic legislation. These provisions could go a long way to fulfilling targets set by COP21. This also means that if Donald Trump were to formally renounce the COP21 agreement, his administration would be gratuitously reneging on an international agreement. On the other hand, a practical decision to desist from previous domestic energy policies would put the US on the same footing as China – signing off on international agreements that they do not, in the end, implement. It would not be the first time this happened in international climate conferences, although the consequences for the planet cannot be overstated.

Building on the idea of a mercantilist China that picks and chooses what issues it engages on, it is worth asking why it eventually signed the COP 21 agreement. In fact, China’s energy and environment policies are barely tied to international commitments at all. They are more closely related to the goals of self-sufficiency and achieving a diversified energy mix. However, on the domestic front, the COP 21 agreement spoke to those concerned about the government not taking action on its domestic smog problem – also referred to as “airpocalypse”.

In the COP21 talks, the EU’s negotiating stance, which promoted ambitious commitments to carbon emission caps, was undermined by both American and Chinese opposition to legally binding agreements. An open repudiation of the agreement by the Trump administration would be even more destructive. If this happens, China will be able to claim the moral high ground over the US, despite, in practice, having given up on implementing the agreement.

Renminbi internationalisation

In a world where geo-economics underpins the global order, an examination of China’s international role has to include the rise of the renminbi as an international currency, and China’s potential leverage over the global financial system. In October 2016, China’s currency became part of the IMF’s Special Drawing Right (SDR) currency basket. This means it is now a “freely used” (but not freely tradable) currency. Attaining international currency status is an important step for China, giving it legitimacy and leverage on the global financial stage. For more than a decade, Chinese officials and experts have talked about the coming internationalisation of the renminbi, and the hype has always distorted the facts. For all the fanfare around internationalisation, the renminbi remains a minor currency in international transactions. According to SWIFT, use of China’s currency in global payments decreased from 2.31 percent in December 2015 to 1.68 percent in December 2016.[15]

Yet currency internationalisation, and the status value it bestows on a country, has played a large role in wooing financiers, central banks, and international financial institutions the world over. Even more so because currency internationalisation has coincided with rising financial clout for China, both in terms of its current account surplus and in terms of direct investment. China has become a global financial leader over the past few decades, but more due to its large currency reserves than by renminbi internationalisation.

To become truly global, a currency must be used for borrowing and not only for trade settlement. China’s central bank has, so far, signed 39 bilateral swap agreements with other central banks, and is creating offshore markets for renminbi lending. But it does not maintain consistency in its exchange policy, which has undermined confidence in the currency. China has switched its exchange rate regime several times – from a peg with the US dollar, to a crawling peg, then to a banded valuation against an unspecified basket of currencies. In 2008, China then reverted back to a fixed peg, before resuming the banded valuation method in 2010. The last change in the valuation method was made in August 2015, when China’s central bank announced that it would, from then on, use a daily fixed valuation estimated by the bank according to market conditions. This last move was widely – and correctly – interpreted by the markets as evidence of a creeping devaluation, bringing a stock market meltdown in the process, which the authorities managed to control by imposing a curb on forward trading. Expectations of continued devaluation fuelled capital flight and, as a result, China’s foreign currency reserves have fallen by a trillion dollars since August 2015. After Trump’s threat of labelling China a currency manipulator, the country unexpectedly reversed course on the renminbi, intervening to prop it up in January 2017 and intensifying capital controls.

Indeed, China’s capital liberalisation, which began in 2010, has also suffered from uncertainty. China’s capital liberalisation has led it to enlarge offshore renminbi (CNH) trading and borrowing, especially in Hong Kong, Singapore, and London. It also extends to the Shanghai-Hong Kong and Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connects. The overseas expansion of Chinese payment systems has also allowed Chinese tourists to spend $224 billion in 2016 alone, though some of this is likely capital flight.

In the cases of both its monetary regime and capital account, the peak of China’s liberalisation came shortly before the IMF decided, in November 2015, that the renminbi could be included in its SDR currency basket. Less than two months after the renminbi became the first non-freely exchangeable currency in the IMF currency basket, authorities imposed new capital controls limiting the ability of Chinese companies to transfer money abroad for acquisitions without central bank authorisation. The threshold for payments requiring authorisation has been set very low, at $5 million. In setting such an authorisation threshold, China has, in effect, frozen the liberalisation of its capital flows.

China is not ready to compete with the United States in monetary or financial terms. In fact, its interrupted transition to a market economy and present inability to lift capital controls make it impossible for the renminbi to become an international reserve currency in the way that the US dollar or the euro are. China’s currency issue is possibly its best-hidden paradox. While the world has fawned over China’s extraordinary foreign currency reserves, the management of its own currency remains tied to the dollar, and it cannot afford, under its present political economy, to have free capital markets. China can be a passenger, benefiting from the world’s present financial architecture, or it can influence its partners with its financial resources, but if it is unable to lift its capital controls, it cannot possibly become the leader of a global financial architecture that relies on free capital movement.

China faces Trump

Whether through its ability to dilute UN resolutions, its reservations on key international treaties, or its reticence to sign legally binding agreements, China is an actor that simultaneously engages with and pushes back against the global order. China has increasingly projected power through its ability to make or break international agreements – the COP 15 or the UN sanctions process being cases in point. But that might be about to change. Donald Trump, with his focus on deal-making and putting America first, is changing the frame of reference for China.

Trump’s presidential campaign put emphasis on questions of international trade and job losses to China. In his inauguration speech he stated that the US has “enriched foreign industry at the expense of American industry”, and that henceforth his policy positions would be motivated by a strategy that put “America first”.[16] In his first week in office Trump revoked the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), signalling to China and the world that his protectionist view on global trade was not just a façade to win votes, but a reality.

There are more doubts on the consistency of his intentions towards China on strategic issues. Trump’s post-election tweets indicated a willingness to speak bluntly to China. His decision to take a call from Taiwan’s president and then to question the One China policy was unprecedented for any US president since Richard Nixon. Trump has also not shied away from suggesting that he could surpass his predecessors in the most substantial aspect of the “pivot to Asia” − strengthening the US navy presence in the Pacific.

But Trump’s words as president have already contradicted his pre-inauguration tweets on China policy, and the administration is not yet solidified, if it will ever be. To confront China on strategic issues requires consistency, steadfastness, and a clear sense of priorities. These are by no means assured at this point. China’s leaders have completely refused to engage in the controversy around Trump so far − a sign that they are waiting for deeds rather than hanging on words.

For China, the US has historically been a more-or-less stable and predictable actor in the international system. Disagreement is built into the US-China relationship, but it is China that is accustomed to providing the surprises, rather than the US. Trump has turned that dynamic on its head. He has extolled the virtue of “uncertainty” as a policy posture to China, reversing decades of dogma in Sino-American relations. Trump’s strategic use of uncertainty stretches beyond trade – China’s main interest – and into security issues too. Even as he berates the EU and loudly proclaims the obsolescence of NATO, he has been clear to reassure primary Asian allies such as Japan and South Korea of their security. Shaking the bedrock of the relationship, Trump’s chief strategist, Steve Bannon, who also has a seat on the National Security Council, has stated that within the next ten years the US would be “going to war in the South China Sea…no doubt”.[17]

The Sino-American relationship has been built on the assumption that it should flourish under conditions of stability and predictability. An added rationale for American engagement was that such conditions could even build a foundation from which trust could enter the relationship. China does not buy-in to such mental schemes, but it has generally sought stability from others in the form of declaratory commitments and clear signalling of intent. The situation today therefore presents a unique dilemma to China.

But for all the discussion about China’s reluctance to honour internationally binding commitments, such as UNCLOS, the US hasn’t always been perfect itself. For instance, the US Senate has refused to ratify the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty since 1999, and has also failed to ratify UNCLOS – even though it professes to abide by its terms. Furthermore, it has consistently refused to submit its own citizens to the International Criminal Court. Campaigns against the UN system in the US have happened in the past − especially under the George W Bush administration, which reduced financing for the organisation. That campaign is being resurrected by some in the current administration. On issues such as climate change and environmental concerns, the US has been much less willing to make firm commitments than the EU or Japan.

The fact that China has been the largest beneficiary of the open international trading system, that it has made at least a political commitment to mitigating climate change through capping carbon emissions, and that it is an increasingly important financial contributor to the UN system, means that it may, ironically, have become one of the nations that are necessary to the global order. One can safely predict that, in the coming months and years, the disaffection of experts and the media with the Trump presidency will result in more conciliatory judgments being bestowed on China’s international behaviour.

If Trump and his administration remain intent on breaking away from free trade in favour of America first, and if they turn their back on environmental policy, this could still present China with a tempting political opportunity. Some more flexibility on issues such as economic opening-up and reciprocity, and more discipline at the expense of domestic energy and industry lobbies, would make China no worse an offender than the US. An American administration that distances itself from its own allies and creates hostility in public opinion would offer China an opportunity to shine at low cost in terms of actual political concessions. Dividing the West – and not simply Europeans among themselves – would be a possibility for China.

Holding China to its word

In tennis, most serious players compete from the back of the court – employing the long game that China has practised so successfully until now. But occasionally one sees a player who rushes to the net and finishes off an adversary. Surprise and disorientation are this player’s assets. Indeed, the surprise act seems to be Trump’s favoured tactic. But no one can hang around at the net for ever. At some point, your adversary will lob the ball over your head.

China’s rise in the past half-century has partly been based on the hard work of its people, on fluctuations in the market economy, and on strong state leadership. Today, China’s GDP per capita, for a population of almost 1.4 billion, exceeds that of at least one EU member state, and its overall GDP − calculated in purchasing power parity terms – exceeded that of the US for the first time at the end of 2016. China has grown into an economic behemoth, yet it is still treated as a developing economy under international agreements signed 15 years ago. With developing economy status come exemptions from global trading and a number of financial rules that govern its activities. Today it is China’s economic stature, rather than its direct challenge to global order – or even its regional shenanigans – that have grabbed the attention of Western societies.

Many Chinese observers and officials have seen the writing on the wall for some time, and as early as the 1990s began reaching beyond Deng Xiaoping’s prescription of “lying low” on the global stage, and taking on more international responsibilities. Only rarely does it oppose international sanctions processes or interventions outright. At the same time, its pledges to international peacekeeping and its commitment, at least in principle, to climate change mitigation indicate a gradual opening-up.

China’s interactions with the global order – whether on climate change, foreign intervention, or international financial institutions – betray a policy of cautious engagement. China relies on a stable global order to preserve the networks that support global free trade. It therefore has a vested interest in protecting that order. Therefore, where China “sets the needle” between engagement and disengagement often appears to be connected to its global economic interests. It is occasionally willing to act against its own principles to preserve good relationships, unlike Russia, which has no qualms about using its veto power at the UN Security Council. Where China draws the line on engagement often tells us more about its philosophy of global order than on what issues it does engage on. China draws the line on issues where its sovereignty – the power of its centralised state to wield total control – is threatened.

The challenge China faces is how to protect a global order that guarantees its economic interests, while the Western backlash against globalisation threatens to undercut the export markets China depends on. Its gradual engagement on the world stage reveals that China is more integrated into the global fabric than it cares to admit.

The upending of American politics by Trump has far-reaching consequences for China. Disillusion with the previous China policy was already ripe. Depending on the strategic focus of the Trump presidency, it could be a spoiler in China’s long game. The “cold peace” – an expression that first gained popularity in China to describe Sino-Japanese relations after 1998 – could be over. All the while, disaffection with Chinese trade mounts in Europe. China’s long game has relied on the West’s interest in an integrated economy, and on the reluctance to enter conflict – something that has also been interpreted by China as a sign of weakness and decline. Alternatively, if Trump withdraws and embraces protectionist objectives, this would vindicate China in its estimation that the US is in a long-term decline, and reveal that it may simply have underestimated the speed of this decline.

The emergence of Trump presents an opportunity for China to step up and become a stabilising force. There are several parts of the international order in which China could claim the mantle, though Chinese leadership is problematic in all of them. China has never proposed or committed to genuinely deep free trade deals, so it would be a leap for China to become a leader in the realm of free trade, even despite its support for globalisation. TPP, like the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), has strong regulatory aspects, and China’s present political economy cannot afford to endure them. Similarly, Chinese leadership on climate change mitigation has been held up as a possibility in the media. But this seems unlikely. Its persistent reliance on coal, oil, and natural gas make a real energy transition very doubtful. Even if the country develops even more significant alternative energy sources, its hunger for energy, to support its industry, would still make it dependent on fossil fuels, assuming its development doesn’t radically change. But appearances count, and an isolationist America would make China’s case for leadership much easier to make.

With an uncertain US and a China whose fickle approach to the international order makes it an unconvincing leader, Europe is challenged from both sides. It must gather its strength to engage the US on defending European security, and maintain faith in its values to hold China accountable on its abstract pledges to the international order.

Recommendations: How should Europe react?

Europe finds itself caught between a US president seemingly at odds with the global order that his country shaped, and a China that is increasingly engaging with that very same order on a mercantilist rather than values-driven basis. How should the EU position itself?

Stay true to the EU’s values

In the current political climate of eroding values and principles, there are two temptations that EU member states need to resist. The first is the temptation to move from the illusion that China has become “more like us” to a cynical strategy where Europe becomes “more like them” as a means of building bridges and cooperating. As tenuous as the EU’s moral high ground may be, it needs to preserve its values and those it has historically shared with the US. Washington should also be reminded of this.

Hold China to its word

In practical terms, this means that the EU should hold China to account on the recent pronouncements made by Xi Jinping and his government regarding multilateralism, the rule of law, free trade, the opening-up of the economy, and reciprocity. China must be challenged to push forward in those areas. After all, there is a strong rationale for conflict avoidance in China, and the country would be the biggest loser from a major setback to globalisation.

But don’t expect China to lead

The second temptation that must be resisted is to think that China could somehow replace the US as a dependable bastion of a free-trading and rules-based world order, let alone of democratic values. China’s political system affords opportunities for sectoral cooperation when it matches Chinese interest. But this fickle approach is simply incompatible with principled implementation of international law and global norms. This is even more true of the post-1989 ambitions for a global liberal order.

Maintain clear priorities

The appearance of Trump, and the more general questioning of globalisation by large sectors of Western societies, means that Europe has to adopt a Janus-faced approach, looking both east and west, to preserve its values. The US has become a priority as Europe attempts to feel out how it can bring back the Trump administration from isolationism. In doing so, Europe should be careful not to let China inadvertently off the hook through pre-occupation with the state of affairs in the US. Europe should take care to ensure its shift in priorities doesn’t make it blind to Chinese infractions. Two wrongs do not make a right.

Work to protect the liberal free trading system

Halfway between values and interests, Europe should also strive to maintain a liberal free trading system – something that still forms the heart of the European economic model. Today, it is at risk of being torn apart by different impulses of varying intensity. One is hostility to Chinese investment – a trend that is part of the so-called populist backlash against globalisation. The other is the US rejection of TPP and Trump’s economic pledge to put “America first”. Screening foreign direct investment on the grounds of preventing technology leaks, and on defence concerns, is not the same as shutting the door to China.

Act as one and know your strengths

There is a risk that recent moves by the EU and member states towards coordinated and demanding policies on trade and investment are scuttled by breakaway EU member states that seek to bilaterally woo Chinese investors. A recent American policy report is advising “fair reciprocity” with China in areas ranging from trade and investment to academic exchange and media.[18] These are exactly the sort of areas where the EU, acting as one, can make a difference. Member states that seek to opportunistically negotiate side deals with China are only undercutting themselves – allowing China to lobby the EU through them. The EU must remain committed to unified negotiation if it is to achieve the results it wants and protect its values on the global stage.

Conclusion

Policy twists and turns on European trade and investment relations with China may seem a small issue in view of larger interrogations of the global order. But the crux of China’s participation in the global order is economic interest. And to protect its economic interests it requires stability. The EU’s track record of achievement and leverage is particularly strong in this area, provided it stands together. Europe can claim a brokering position on trade and economic issues because China cannot afford to single out Europe in trade spats when faced with the most unpredictable and possibly combative US administration since the second world war. Europe must take China to task on its own words. But the EU must continue to be mindful of China’s assertiveness and shortcomings towards the international order if it wants to protect its values. Getting the balance right between admonishing China and engaging it requires cool heads and Europe-wide coordination.

In his speech at Davos, Xi mentioned that “we live in a world of contradictions”. Perhaps those contradictions are about to become ever more stark. Europe must hold firm and stand its ground.

[1] President Xi’s speech to Davos in full, 17 January 2017, available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/full-text-of-xi-jinping-keynote-at-the-world-economic-forum (hereafter, Xi’s speech).

[2] Xi’s speech.

[3] Theodore Schleifer and Jeremy Diamond, “Trump: ‘Everything is negotiable’”, CNN, 1 March 2016, available at http://edition.cnn.com/2016/02/29/politics/ted-cruz-new-york-times-immigration-tape/.

[4] David H. Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson, “The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, No. 21906, January 2016, available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w21906.

[5] François Godement, “Big is Beautiful? State-owned Enterprise Mergers Under Xi Jingping”, China Analysis, November 2016, available at https://ecfr.eu/page/-/China_Analysis_%E2%80%93_Big_is_Beautiful.pdf.

[6] “Putting the Order(s) Shift in Perspective”, Speech by Fu Ying at the Munich Security Conference, 13 February 2016, available at https://www.securityconference.de/en/activities/munich-security-conference/msc-2016/speeches/speech-by-fu-ying/.

[7] Contributions to UNHCR for the budget year 2016, available at http://www.unhcr.org/575e74567.html.

[8] “Libya conflict: reactions around the world”, the Guardian, 30 March 2011, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/mar/30/libya-conflict-reactions-world.

[9] Marie Bourreau, “Comment la Chine aide la Corée du Nord à contourner les sanctions de l’ONU”, Le Monde, 3 March 2017, available at http://abonnes.lemonde.fr/asie-pacifique/article/2017/03/03/comment-la-chine-aide-la-coree-du-nord-a-contourner-les-sanctions-de-l-onu_5088703_3216.html?xtmc=sanctions_coree_du_nord&xtcr=2.

[10] Jane Perlez, “Xi Jinping’s US visit”, the New York Times, 28 September 2015, available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/projects/cp/reporters-notebook/xi-jinping-visit/china-surprisesu-n-with-100-million-and-thousands-of-troops-for-peacekeeping.

[11] Declarations and statements, United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, available at http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_declarations.htm#China%20Upon%20ratification.

[12] Robert D. Williams, “Tribunal Issues Landmark Ruling in South China Sea Arbitration”, LawFare blog, 12 July 2016, available at https://www.lawfareblog.com/tribunal-issues-landmark-ruling-south-china-sea-arbitration.

[13] See this compelling account of the talks by an eyewitness: Mark Lynas, “How do I know China wrecked the Copenhagen deal? I was in the room”, the Guardian, 22 December 2009, available at https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/dec/22/copenhagen-climate-change-mark-lynas.

[14] Isabel Hilton, “With Trump, China Emerges As Global Leader on Climate”, Yale Environment 360, 21 November 2016, available at http://e360.yale.edu/features/with_trump_china_stands_along_as_global_climate_leader.

[15] Li Dongmei, “SWIFT Says RMB Internationalization Stalled Last Year”, China Money Network, 26 January 2017, available at https://www.chinamoneynetwork.com/2017/01/26/swift-says-rmb-internationalization-stalled-last-year.

[16] Aaron Blake, “Trump’s inauguration speech transcript, annotated”, the Washington Post, 20 January 2017, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/01/20/donald-trumps-full-inauguration-speech-transcript-annotated/?utm_term=.20be17854a64.

[17] Benjamin Haas, “Steve Bannon: ‘We’re going to war in the South China Sea…no doubt’”, the Guardian, 2 February 2017, available at https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/feb/02/steve-bannon-donald-trump-war-south-china-sea-no-doubt.

[18] Orville Schell and Susan L. Shirk, “US Policy Toward China: Recommendations for a New Administration”, Asia Society, Task Force Report, February 2017, available at http://asiasociety.org/files/US-China_Task_Force_Report_FINAL.pdf.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.