Beyond good and evil: Why Europe should bring ISIS foreign fighters home

Summary

- Hundreds of EU citizens who joined ISIS abroad are in detention in northern Syria, a territory whose future is deeply uncertain.

- EU governments remain extremely reluctant to bring these detainees back home and have instead sought to have them tried in the region.

- Sending suspects to Iraqi courts or an international tribunal also appear to be non-starters given the risk of unfair trials and questionable legal footing available.

- Returning European ISIS supporters to Europe is the best way to ensure they remain under control and can be prosecuted, interrogated, and helped with re-engagement as necessary.

- Repatriation would also help the plight of European children in detention camps, who are now at risk of illness and further radicalisation.

Introduction

The dilemma was all too predictable. As forces fighting the Islamic State group (ISIS) succeeded in pushing it back in recent years, it was clear that they were soon likely to gain control of large numbers of the organisation’s members and followers – including many from European countries. Yet, seven months after the fall of ISIS’s last bastion in Syria, EU member states have still failed to come up with a coherent policy on how to handle the hundreds of their citizens who travelled to join the terrorist group, and who are now in the hands of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Turkey’s recent incursion into northern Syria has given sudden urgency to the problem. Fighting between Turkish-led forces and the SDF has affected some of the areas where detainees are held, and several have reportedly been freed or escaped. In other camps, Kurdish authorities have reportedly cut the number of security guards, and there is growing unrest.

This increased instability in northern Syria means that European governments now face a risk that more of their citizens held as ISIS members could escape and rejoin the group, perhaps becoming involved in further attacks or recruitment, either in the Middle East or back in Europe. There is also a danger that fighters and their families will end up in the hands of the Syrian regime. Already conditions in the overcrowded and insanitary refugee camps are putting children’s lives in jeopardy. These conditions also risk strengthening the radicalisation of women and children and making the task of reintegrating them into their own societies much more difficult.

Even before Turkey’s move, it was clear that the SDF did not have the capacity to make long-term arrangements for the many thousands of ISIS members it had captured. The prisons and refugee camps in which the SDF is holding them are, at best, temporary expedients. Officials from European governments, speaking off the record, conceded in recent months that the policy of leaving their citizens in these conditions was not sustainable in the longer term. Yet European countries delayed taking action, because they were determined not to bring their citizens back home but did not have any alternative proposal for dealing with them. European countries have taken back only small numbers of people, almost all of them children.

Bringing European ISIS fighters and supporters back home has a number of difficulties associated with it. Some individuals could still pose a threat, it may be hard to prosecute returnees in some cases, and – above all – repatriating ISIS members is politically unpopular. But doing so also has advantages over any of the options for prosecuting foreign fighters in the Middle East. This paper explores: the emergence of the problem of European ISIS fighters in Syria; Europe’s response until now; and the policy alternatives EU member states could yet hope to try. The paper concludes that the most feasible and effective way forward is repatriation of European ISIS fighters and supporters back to their home countries.

The evolution of the problem

The complex situation of ISIS fighters

The complications surrounding detained European ISIS supporters stem from the ambiguity of their situation. In a world where state borders are still fundamentally important to the operation and application of law, the detainees are suspended in a limbo created by the interaction of two territorial entities that both fell short of statehood.

The declaration of the Islamic State in 2014 drew huge numbers of people to its territory. Altogether at least 40,000 people travelled to join ISIS – more than the number of foreign fighters in all other recent jihadist campaigns combined. It is estimated that more than 5,000 of them came from Europe. Because of its state-like nature, the group attracted not just fighters but many people who wanted to make their lives in the reborn caliphate. To many Europeans, these recruits seemed to be turning their back on their native country and joining a hostile state. As French foreign minister Jean-Yves Le Drian has said, “French nationals who fought for Daesh [ISIS] fought against France. Therefore, they are enemies.” But the Islamic State was not recognised by any country, and the opposing coalition eventually reconquered all the territory it controlled.

The forces that gained control of the final bloc of that territory, and captured the majority of ISIS detainees, also fought on behalf of a non-state group. The SDF was led by the Kurdish YPG (People’s Defence Units) and the Kurdish autonomous administration in Syria now controls the prisons and refugee camps in which the captured ISIS supporters are being held. The Kurdish authorities do not have the resources or structures to prosecute their captives or to look after the needs of the tens of thousands of people they hold. Because the Kurdish administration is not a state, European countries cannot conclude an international agreement with it on handling the detainees; and Europe will not consider negotiating with the Syrian regime over the detainees’ fate. Iraq has prosecuted the foreign fighters it holds within its domestic justice system, while Turkey aims to deport many of them back to their countries of origin – though the process can be slowed by difficulties in identifying detainees. But the SDF holds the majority of foreign fighters and other ISIS supporters, and these captives and internees remain in limbo.

How many European ISIS supporters are in Syria?

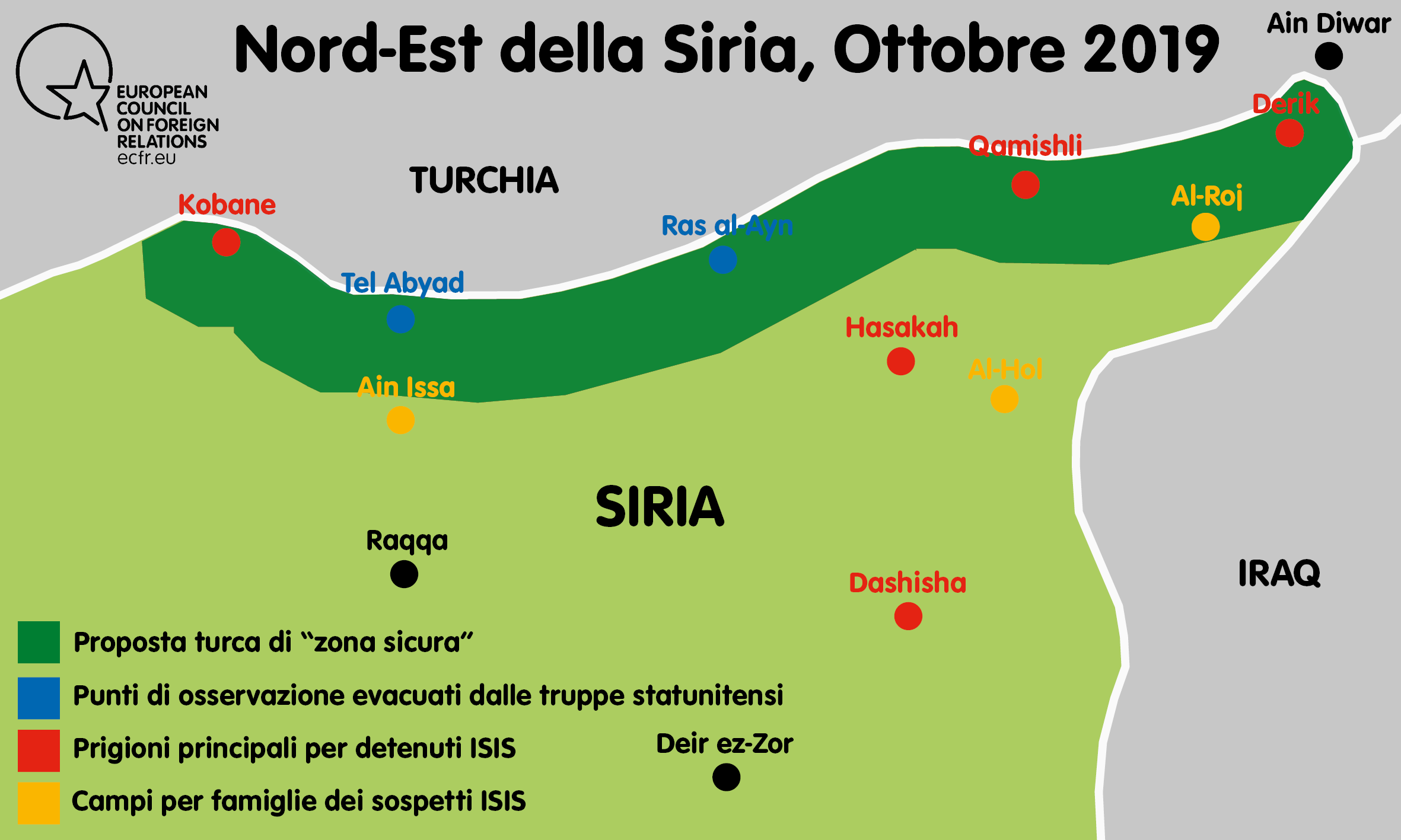

It is hard to establish precise figures for the number of European citizens being held as alleged ISIS members or supporters in Syria. There are thought to be around 10,000 men detained by the SDF, of whom around 2,000 are “foreign” (meaning not from Syria or Iraq). An SDF presentation given to a group of states and NGOs earlier this year suggested that only 10 percent of these, or around 200 people, were from Europe, including countries like Ukraine and Kosovo. Other SDF and NGO estimates have been higher. The detained men are held in a series of prisons and makeshift “pop-up” prisons across north-east Syria, with the largest facilities thought to be in Hasakah and Dashisha.

Women and children have been held in three large refugee camps, at al-Hol, al-Roj, and Ain Issa. Most, though not all, of the foreigners have been housed in an annex of al-Hol. UNHCR estimates that there are 11,000 people in the annex, of whom 27 percent are women and 67 percent children under the age of 12.

A recent study by the Egmont Institute estimated that there were altogether around 400-500 adults (including men and women) from EU member states detained in Syria, and around 700-750 children. The largest contingent is French – according to the Egmont study, this comprises 130 adults and 270-320 children. The other countries with significant numbers of detainees are Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Sweden.

Life in the camps

Conditions in the camps are desperate. Reports detail a lack of sanitation, inadequate medical facilities, and widespread trauma among young children. In al-Hol, where most European women and children are held, the most radical residents have taken control of much of the camp. They intimidate and punish women judged to be insufficiently observant, and a climate of lawlessness prevails. Since Turkish forces moved into Syria, the SDF has warned of the difficulties it faces in guarding camps and defending its territory. Already, ISIS’s leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, had called for the group to focus on breaking men and women out of detention. As fighting spread near Ain Issa, a group of women and children, numbering several hundred according to some reports, were able to leave; European sources have indicated that several French and Belgian women and children were among them. It also appears that a small group of men escaped a prison for fighters in Qamishli. If the ceasefire announced on 17 October holds, it is unclear what will happen to al-Roj camp, which sits within the “safe zone” that the SDF has apparently agreed to withdraw its forces from.

The realignment of forces under way in north-east Syria since the withdrawal of US troops also raises another danger. The SDF says the deal it recently reached with the Syrian regime was a purely military agreement and that the SDF will continue to administer camps and prisons holding foreign ISIS supporters. But this could change. If Bashar al-Assad were to gain control over European foreign fighters and family members, he could use them as a bargaining chip to gain recognition from European leaders. Meanwhile, hundreds of European citizens, including many children, would be at risk of abuse in the Syrian regime’s notorious prison system.

Current European approaches

Keeping European citizens away

So far, European countries’ response to their detained ISIS supporters has been shaped by their governments’ determination not to bring them back home. Europe is following an approach that is comparable to its ‘externalisation’ strategy on migration, through which it has tried to have would-be immigrants’ entry applications processed in third countries, especially in north Africa. The difference in this case is that governments are trying to keep away their own citizens. Some countries have taken active steps to prevent individuals from returning by revoking their citizenship. More often, they have simply avoided taking responsibility for their nationals, relying on the fact that they are not free to move and therefore cannot return home. European governments say they are reluctant to repatriate their citizens because they think many of them would pose a security threat, and that there are no fully satisfactory options for handling them at home.[1]

Officials believe that – in contrast to some earlier returnees, who may have left the region after becoming disillusioned with ISIS – fighters in detention now are more likely to be hardcore believers in ISIS’s ideology. As British defence secretary Ben Wallace has said, “They are the diehards. They are definitely in some cases dangerous.” According to Alex Younger, head of the United Kingdom’s secret intelligence service MI6, returnees “are likely to have acquired the skills and connections that make them potentially very dangerous.”

European governments view not just men as a threat, but women too. The Dutch justice minister, Ferd Grapperhaus, announced in September 2019 that he had turned down US assistance in repatriating ten Dutchwomen because their return could lead to “direct risks to the national security of the Netherlands” and other European countries. Influenced in part by the discovery of a plot by a group of Frenchwomen to bomb Notre-Dame cathedral in 2016, European governments have shifted to much more regularly investigating and prosecuting women who have returned from ISIS’s territory. Even when they are not directly involved in planning attacks, officials fear that returnees could radicalise other people or connect them with jihadist networks.

Public opinion in most European countries is also strongly opposed to repatriating adult ISIS members. One recent opinion poll showed that 89 percent of French respondents were worried about the prospect of ISIS members being returned to France. Fear of a public backlash lies behind much of the European hesitation on repatriating foreign fighters and ISIS supporters.

Italy is the only EU member state that is known to have taken back an adult ISIS supporter from the SDF since the recapture of the final enclave of ISIS territory in March 2019. Samir Bougana, a 25-year-old Italian citizen of Moroccan origin, was returned to Italy in June 2019 after being captured a year earlier by Syrian Kurds while trying to flee to Turkey. Bougana faces charges stemming from 2015 of participation in a terrorist organisation. Josep Borrell, the Spanish foreign minister, said in his hearing before the European Parliament for the position of EU high representative that Spain was also preparing to take back the few Spanish foreign fighters held in Syria.

Prosecution in Europe

Following the adoption of United Nations Security Council resolution 2178 in September 2014, which required states to pass laws to suppress foreign fighters, most European countries now have legislation that would allow the prosecution of returnees for belonging to or supporting a terrorist group. Sweden is an exception: a legal amendment introduced in 2016 criminalised travel for the purposes of terrorism, but not membership of a terrorist organisation, leaving those who left the country before that date outside the law’s scope. There are, however, significant variations between EU member states in how the relevant crimes are defined, and the jurisprudence surrounding these laws is still evolving.

European courts have convicted men on the basis of them being registered as fighters in ISIS documents. They have also convicted women for participating in terrorism through providing logistical support including cooking and looking after the household for their husbands who were ISIS fighters. It is unlikely, however, that merely being present in the area formerly controlled by ISIS would be sufficient for conviction in many cases. Many captured men claim to have fulfilled non-fighting roles such as ambulance drivers or cooks, and such claims can be hard to disprove when prosecutors lack evidence.

In many European jurisdictions, the sentences available for those convicted of membership of terrorist organisations are limited to a few years’ imprisonment. The average sentence in Belgium for returned foreign fighters has been five years in jail. In July 2019, a German woman who had married an ISIS fighter was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment for joining a foreign terrorist organisation. The recent average sentence in the UK for membership of a terrorist group has been seven years. France stands out among EU member states for imposing relatively long sentences for the crime of “association of wrongdoing in relation to a terrorist enterprise” – for example, in 2018 the Paris Assize Court sentenced a defendant to 14 years in prison (out of a maximum sentence of 20 years) for fighting on behalf of the al-Nusra Front and ISIS. European officials worry that bringing ISIS members home for prosecution could in many cases result in their being freed on licence in three or four years’ time, leaving security services with the burden of monitoring their activity.

Longer sentences are available for ISIS members who can be prosecuted for additional crimes such as killing civilians, torture, or enslavement. But that requires clear evidence. There is a variety of sources of evidence to tie defendants to crimes of violence: testimony from victims, colleagues, or family members; social media evidence including photographs and messages boasting about the defendant’s activities or attempting to recruit others; battlefield evidence including ISIS membership forms, mobile phones, computer hard drives, and fingerprints on weapons; and evidence from intercepts and other intelligence sources. Not all of this evidence is admissible, however, in all EU member states. The UK, for example, prohibits the use of intercept evidence in court. Germany has restrictions on the use of social media posts as evidence.

In addition, collecting evidence in northern Syria presents significant challenges, particularly in the uncertain aftermath of Turkey’s incursion. European governments worry that evidence passed on by partner forces such as the SDF may not meet the requirements of being documented and looked after in a way that would ensure admissibility in domestic courts. And the British government in particular is concerned that defendants could seek to have charges dismissed on the grounds that they were returned from Syria to Europe through an unlawful process, although some legal experts believe these concerns are overstated and that solutions could easily be found.[2]

In any case, imprisonment also poses potential difficulties. In the words of the EU’s counterterrorism coordinator, Gilles de Kerchove, “prisons are often an incubator of radicalisation” and there is a danger that imprisoned foreign fighters could influence other inmates. A significant proportion of European foreign fighters were converted to jihadism while in prison. Mehdi Nemmouche, the French foreign fighter who killed four people in an attack on the Jewish Museum in Brussels in 2014, was said to have become radicalised while behind bars. European countries have addressed this danger by shifting towards the use of specialised units for those convicted of jihadist crimes, though approaches vary across the EU. Member states have also developed rehabilitation and disengagement programmes to work with convicts while in prison and after release, to encourage them to move away from violence and help them reintegrate into society. Experts acknowledge, however, that it is too early to speak with confidence about the longer-term prospects for these programmes’ success.

Removal of citizenship

To limit the risk of return, the UK has revoked the citizenship of several British nationals who travelled to join ISIS in the Middle East. It is against international law to make someone stateless, but the UK has removed citizenship of dual nationals and individuals who are, according to the government, entitled to citizenship of another country. The most high-profile case was that of Shamima Begum, who had travelled to join ISIS as a 15-year-old in 2015. Begum has no other nationality, but the British government says she is entitled to Bangladeshi citizenship; Begum’s family is appealing the decision. The UK also revoked the citizenship of Jack Letts, a Muslim convert who joined ISIS from Britain in 2014 and who has Canadian citizenship through his father. The Canadian government said that the UK had taken a “unilateral action to offload their responsibilities”. In 2018, Britain removed the citizenship of Alexanda Kotey and El Shafee Elsheikh, two of a group known as the “Beatles” by their captives, who are now being held by the United States.

Other European countries also have laws allowing the removal of citizenship. Germany introduced a law in April 2019 allowing it to revoke the citizenship of adults who possess a second nationality and who take part in combat operations for a terrorist militia. The law is not retrospective so would only apply in future cases. Denmark announced plans for a similar law in October 2019. In other EU member states, deprivation of citizenship is allowed following conviction for terrorist offences. The increasing attention to revoking citizenship shows how European countries have focused on exclusion as a policy response to foreign fighters, but the measure does nothing to promote accountability for terrorist crimes or due process for the alleged terrorist. It merely displaces the responsibility onto others.

Repatriation of children

The only group for whom many European countries have arranged returns is the children of ISIS supporters. European leaders and officials acknowledge that, even though some children may pose some degree of threat, they should be seen above all as victims. Most European countries accept a responsibility to offer help to children who were either taken to the region by their parents or were born there. The returns of children show that it is logistically possible for European countries to arrange repatriation of their citizens. Yet the repatriation of children has proceeded haltingly and in numbers that are tiny in comparison to the population of children in the camps with European parents. The SDF does not allow separation of children from mothers against the mother’s wishes, and European countries are opposed to bringing mothers home. Therefore almost all the children returned so far have been orphans. In these cases, establishing the children’s nationality is sometimes a slow and difficult process.

France has brought back 17 children in recent months, including two whose mother gave permission for them to leave. Belgium repatriated five children and one young woman in June 2019, while Sweden accepted seven orphans in May. A German delegation accepted the handover of four children, including one ill child of six months whose mother gave permission for the transfer. The UK has not had an announced policy of returning orphans, but its foreign secretary said on 15 October that the government was now looking at whether they could be repatriated. Denmark has accepted a sick child, but recently passed a law that strips children born abroad to Danish foreign fighters of the automatic right to Danish citizenship.

In some European countries, relatives of those detained have launched legal action to compel governments to repatriate children and mothers together. In France, lawyers for a group of relatives have challenged the foreign minister before the Court of Justice of the Republic, a special court that tries cases of ministerial misconduct. Cases have also been launched in Germany and Belgium, though in no case yet has a final ruling been issued that requires repatriation. Nevertheless, government officials anticipate increasing legal pressure to bring back children and parents together.

What other countries are doing

EU member states’ reluctance to take back detained foreign fighters and ISIS supporters stands in contrast to the record of some other countries that have repatriated significant numbers of detainees. In April 2019, Kosovo brought back 110 of its citizens (four men, 32 women, and 74 children) from SDF custody with US assistance. The men were detained pending prosecution, while the women and children were allowed to return home together, with the women placed under house arrest.

Central Asian countries have brought home large numbers of ISIS supporters from SDF detention, as well as repatriating children from Iraq. By June this year, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan had repatriated 756 of their citizens, according to Human Rights Watch. Uzbekistan arranged an airlift for a reported 148 women and children from SDF custody in May 2019; they were taken by bus to Qamishli, and then flown to Russia’s air base in Syria for transfer home. Between January and May 2019 Kazakhstan reportedly repatriated 524 of its citizens – 357 children, 137 women, and 30 men. These countries claim to have rehabilitation programmes for women and children, though critics claim they focus more on outward indicators like clothing rather than on underlying attitudes.

Approaches under consideration in Europe

Prosecution in Syria and Iraq

European officials have frequently said that the most appropriate place for foreign fighters to be tried is in the region where they committed their crimes. This approach sounds reasonable in theory, but it would not justify trials that would likely be unfair, nor long delays in delivering justice or releasing anyone who is acquitted. There are some practical advantages to conducting trials in a location near victims, witnesses, and evidence, but practicality should not be used as a pretext for the use of local justice systems that fail to apply due process and violate defendants’ rights in other ways.

Some EU countries have explored the possibility of prosecuting detainees in the Kurdish area of Syria. But even before the Turkish incursion, the obstacles seemed too great for this to be feasible. An international tribunal could not be set up in Syria without the consent of the Syrian regime. According to EU sources, the Kurdish authorities have said they would be willing to prosecute and imprison foreign fighters themselves if they were given enough international assistance, but that would require a massive and time-consuming investment in building up the local justice system and prison infrastructure. Doing this without the approval of the Syrian government would be politically controversial. It would also be certain to provoke strong Turkish opposition.

For these reasons, European attention has focused increasingly on trying foreign fighters in Iraq. Two options have been considered: prosecuting foreign fighters within the Iraqi justice system; and setting up some form of tribunal with international involvement.

Iraq has already prosecuted many foreign men and women, including some Europeans, for terrorist crimes in the last few years. These include both people captured in Iraq by Iraqi or partner forces, and a smaller number transferred to the Iraqi authorities by the SDF. Many of those convicted have been sentenced to death, though none are known to have been executed yet. The proceedings have been widely criticised. According to Human Rights Watch’s Belkis Wille, who has followed the trials closely, there have been problems with the conditions in which prisoners were held, with the lack of access to adequate defence lawyers, with trials being rushed, and with convictions usually based solely on a confession and no other supporting evidence. According to Wille, torture is widely practised in the Iraqi justice system as a method to extract confessions. Arguments made by some defendants (for instance, women claiming that their husbands had brought them into ISIS territory against their will) have been ignored. In addition, victims of ISIS abuse have no role in the proceedings.[3]

In some cases, defendants have been sentenced to death or to life imprisonment for membership of ISIS after trials lasting only a few minutes. One detainee transferred from Syria and sentenced to death in Iraq alleged that he had been convicted on the basis of fabricated evidence designed to show that he fought on Iraqi territory, making it easier for Iraqi courts to assert jurisdiction in his case. Iraq’s penal code gives courts jurisdiction over people committing offences outside Iraq if these affect the “internal or external security of the state”. The Iraqi judiciary formerly interpreted this provision in a way that did not cover non-Iraqi ISIS members who had never crossed into Iraqi territory, though Wille notes that some senior judges have recently changed their position, now saying they can assert jurisdiction over all alleged ISIS members anywhere outside Iraq.

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) prohibits any state party from transferring its nationals to a country where they are at risk of being sentenced to death. The French government faced widespread criticism after the SDF transferred at least 11 Frenchmen to the Iraqi authorities in early 2019. Many of them were subsequently sentenced to death. The French government has denied that it was involved in arranging the transfer, and has called for the death penalty to be waived in these cases. But there have been press reports that France played a role in approving the transfer; the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, Agnès Callamard, said she was “particularly disturbed” by reports that France played a role in the operation, adding that she found the stories credible.

To avoid the problem of the death penalty, European countries have reportedly shifted to considering the creation of special chambers within the Iraqi justice system to try foreign fighters. These chambers, perhaps set up through a formal agreement with European countries, could exclude the use of capital punishment and follow at least minimal standards of due process. Speaking at the UN in September 2019, Iraq’s foreign minister, Mohamed Ali al-Hakim, said that the death penalty was one of the issues being discussed between Iraq and international partners; he did not rule out prohibiting it in the case of non-Iraqi defendants. In exchange, European countries would have to pay substantial sums to cover the costs of trying and imprisoning foreign fighters. According to press reports, Iraq has proposed an initial payment of $2 billion, calculated on the basis of the costs of the US detention regime at Guantanamo Bay. If an agreement includes payments on anything like this scale, prosecutions in Iraq could turn out to be a very expensive option for EU member states.

This arrangement might require an amendment to the Iraqi constitution, in which Article 95 prohibits the establishment of special or extraordinary courts. A bigger problem is the broader deficiencies of Iraq’s justice system. Even if the death penalty was banned, it would be an enormous task to establish detention and trial procedures that complied with human rights obligations and ruled out torture, and to monitor the courts to ensure they followed these procedures. Yet European countries that transferred their citizens to Iraq without these guarantees would violate their obligations under the ECHR and the Convention against Torture. Press reports also suggest these chambers might only prosecute fighters, leaving European countries to take care of women affiliated with ISIS. If the chambers also prosecuted women, European countries would need to take care of their children; repatriating them would mean the children growing up thousands of miles away from their mothers.

An international tribunal

An alternative option that some European countries have looked at is to establish an international tribunal in the region to try at least some ISIS fighters. The Swedish interior minister convened a meeting of European officials in June 2019 to promote the idea. Setting up a tribunal is an attractive idea in some ways and would fit with Europe’s traditional support for international justice. But it would raise questions about the scope of jurisdiction, would take a long time, and would probably only be able to prosecute a small fraction of the ISIS detainees in Syria. Traditionally, international courts have prosecuted those most responsible for serious crimes – not large numbers of low-level foot soldiers.

Since all EU member states are party to the International Criminal Court, it would have jurisdiction over international crimes committed by their citizens. However, this would only extend to those who could be charged with genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes – not membership of a terrorist group. For these reasons, officials have discussed setting up a new tribunal, probably in the form of a ‘hybrid’ international-national court established in association with Iraq.

One problem here would be the question of who the court could prosecute. Setting up an international tribunal that only had jurisdiction over suspected ISIS members, and that ignored the many other international crimes committed in Syria, would seem like selective justice. But Iraq would be unlikely to accept a tribunal that could investigate the Syrian regime and other parties to the conflict. Indeed, there has been no sign that Iraq is prepared to accept any international element in prosecuting terrorists on its territory, which it might regard as a slight on its national justice system. If it were to agree, an international tribunal could prosecute some higher-level ISIS members or those linked to particularly serious crimes, but would still leave most detainees to be handled in another way.

Repatriating ISIS members to Europe

Despite the complications involved, bringing European ISIS fighters and followers home remains the most feasible option for delivering justice for ISIS’s crimes. It also has advantages that no other options offer. For instance, some foreign fighters may be linked to crimes in Europe: according to the French terrorism analyst Jean-Charles Brisard, the French ISIS member Adrien Guihal, now detained in Syria, had links to the Nice truck attack in July 2016 that killed 86 people. In such cases, a domestic trial offers the best chance of a successful prosecution that establishes the defendant’s full responsibility and delivers justice to victims at home. More generally, European prosecutors have the experience and sophistication to build fair and effective cases against fighters and other ISIS members, including through the testimony of other ISIS followers and domestic contacts. Many cases have already been developed and several foreign fighters have been the subject of trials in absentia.

Repatriating detainees will also make it easier for security services to question ISIS members in order to gain intelligence about the group’s methods and activities. Some terrorism researchers, such as Brian Jenkins, believe a number of returnees could be turned into assets who would help discourage others from following their course. For those who cannot be prosecuted, or those who have been released, European governments have extensive powers to restrict their movement or monitor their activities through means such as conventional or electronic surveillance and house arrest. Such measures are expensive and time-consuming for security services, but they would be a bargain compared to some of the figures that have been floated for trial and imprisonment of foreign fighters in Iraq. It is far easier to keep track of fighters who have returned home than those who might escape in Syria and join jihadist groups in the region or elsewhere.

Repatriation is the only path that offers a comprehensive solution for the full range of European citizens detained in Syria, based on a case-by-case assessment of each individual’s responsibility for crimes and commitment to violence. The European population in the SDF’s prisons and camps represents a diverse group, including: ISIS members responsible for multiple terrorist attacks and dedicated believers; individuals who may not have been fully committed to ISIS’s agenda but who lacked the initiative to defect; and, of course, children. While some foreign fighters may pose a direct threat if brought home, it is easy to exaggerate the likelihood that they will carry out attacks. Research has shown that almost all attempted plots occur in the first year after return, meaning that intensive surveillance might only be required for a limited time. In recent years, European security services have improved information sharing and refined their counterterrorism approaches in ways that have allowed them to mitigate the threat of returnees and jihadists at home.[4]

Bringing captured ISIS members home would also allow European governments to put some of them into disengagement programmes to direct them away from violence, instead of leaving them in an environment that only promotes alienation. In particular, welfare services could start working with the hundreds of children in the camps following their return, in order to begin healing the trauma they have suffered and reintegrating them into their own societies.

Conclusion

European countries should end their policy of denial and look for the first available opportunity to start repatriating detained ISIS supporters from Syria. Doing so offers numerous advantages, providing ways of: distinguishing between the different categories of European ISIS supporters; establishing their responsibility for specific crimes through fair and well-conducted trials; and using the information they possess to learn more about ISIS. The potential threat that returnees could pose, and difficulties in prosecuting them, may well be exaggerated, and ways exist for European governments to mitigate them.[5]

Repatriation would also be the fastest way to move detainees out of the situation of instability they currently find themselves in. It would limit both the risk of losing control of committed ISIS supporters and the harm that delay is inflicting on hundreds of children.

Were a ceasefire to take hold, an opening would emerge to begin repatriation operations. As a first step, European governments should put plans in place to move quickly once such an opportunity appears. They could then withdraw a certain number of their nationals in a controlled way, giving their own domestic services a chance to begin processing returnees. It may be best to arrange this as a coordinated action involving detainees from several European countries, in order to help countries without resources on the ground, but also to minimise the political backlash in any one country. French and British special forces could play a supporting role, and the most likely extraction route would be through Iraq, with the cooperation of SDF and Iraqi forces.

It will require some political courage for European governments to bring ISIS fighters and supporters home. But they will have to take action sooner or later, and in the meantime the costs of their current policy are clear. No other approach seems feasible or without serious drawbacks. Delaying further would be irresponsible, and only risk creating further problems.

About the author

Anthony Dworkin is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He leads the organisation’s work in the areas of human rights, democracy, and justice. Among other subjects, Dworkin has written on European and US frameworks for counterterrorism, the European Union’s support for transition in north Africa, and the changing international order. He is also a visiting lecturer at the Paris School of International Affairs at Sciences Po.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Olivia Sundberg Diez for excellent research assistance with this project. At an early stage of the project, I was able to present some initial ideas on a panel at ECFR’s Paris office alongside Marc Hecker, Sharon Weill, and Manuel Lafont Rapnouil, and I benefited a lot from their presentations and comments. Within ECFR I would like to thank Julien Barnes-Dacey and Jeremy Shapiro for their help, and Adam Harrison and Chris Raggett for their editorial support.

ECFR extends its gratitude to the Ministries of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for their support for ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa Programme.

Footnotes

[1] In addition to quoted sources, the following paragraphs draw on a series of unattributable conversations with government officials in European countries.

[2] ECFR interview with Maya Foa, Reprieve, 22 October 2019.

[3] ECFR interview with Belkis Wille, 13 October 2019.

[4] https://www.american.edu/spa/news/malet-foreign-fighters.cfm

[5] Daniel Byman, Road Warriors: Foreign Fighters in the Armies of Jihad (Oxford University Press, 2019), pp. 222-228.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.