Connectivity wars

This essay introduces “Connectivity Wars“, an essay collection on why migration, finance and trade are the geo-economic battlegrounds of the future

This essay introduces “Connectivity Wars“, an essay collection on why migration, finance and trade are the geo-economic battlegrounds of the future. It is part of Rethink: Europe, a joint initiative by ECFR and Stiftung Mercator

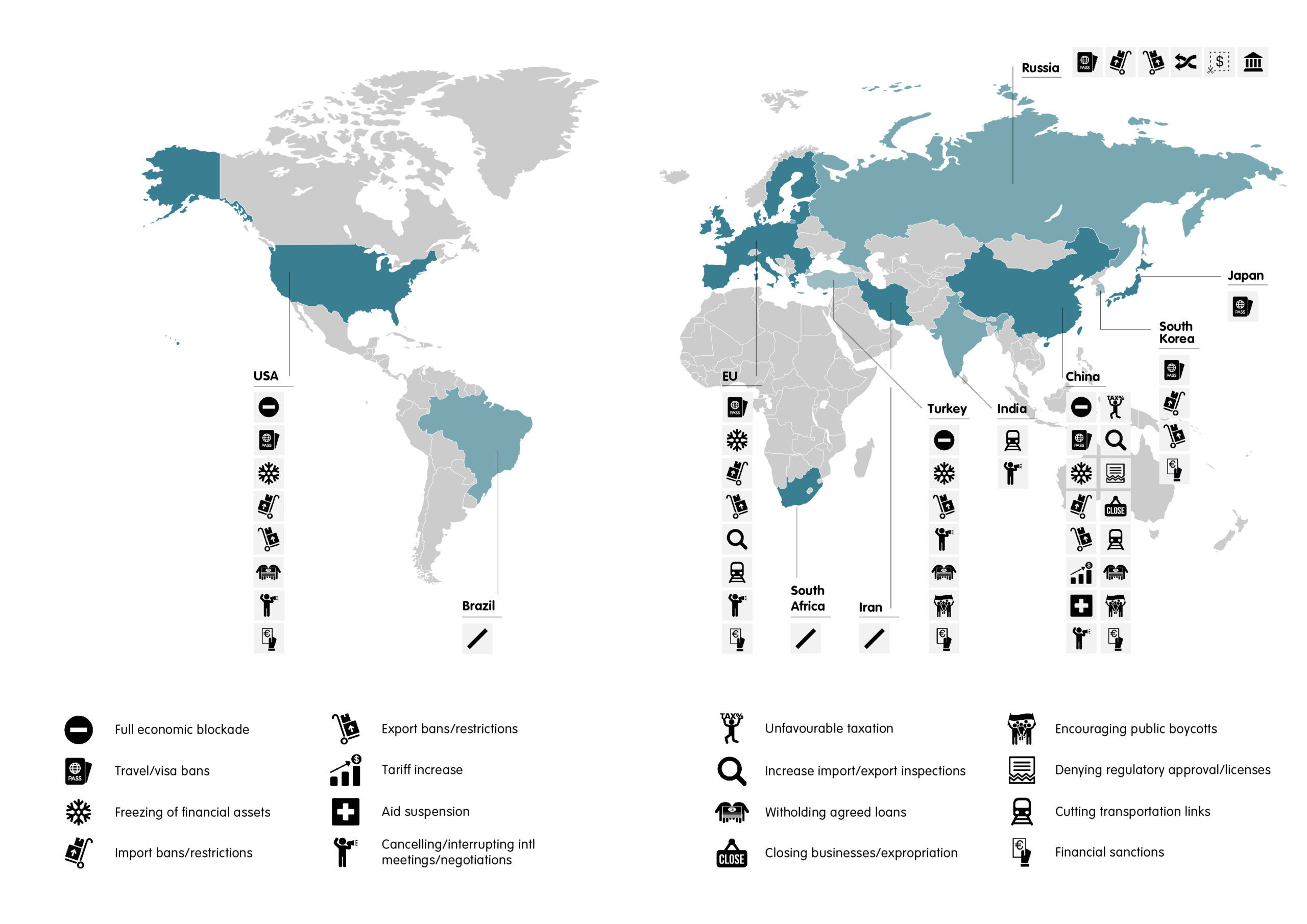

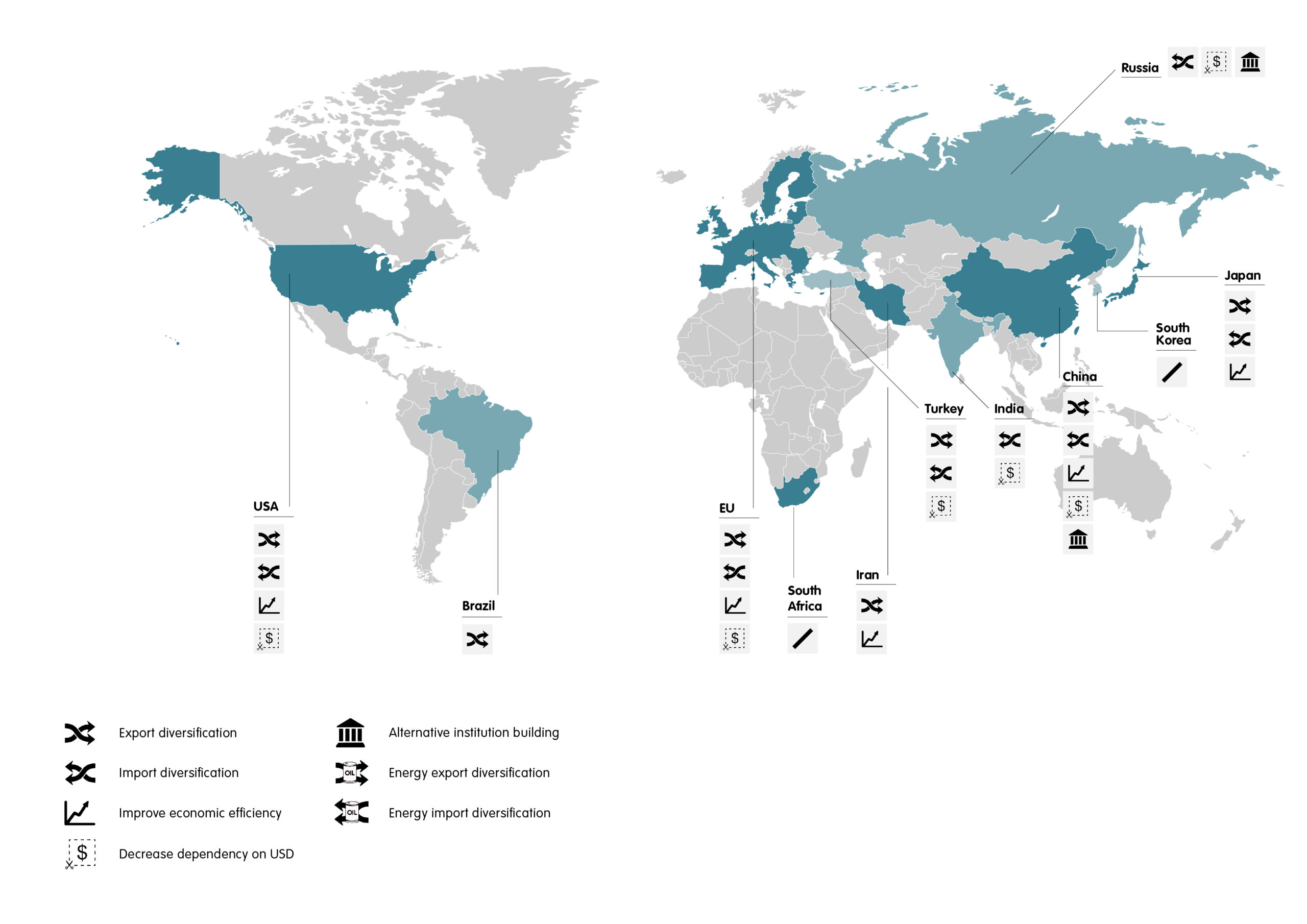

Weaponising interdependence

When Turkey shot down a Russian fighter jet in November 2015, the image of the falling plane went viral. Calls for revenge exploded across the Russian media and internet. Protesters hurled stones and eggs at the Turkish embassy in Moscow. And the high-profile host of Russia’s main political TV talk show compared the downing of the jet to the 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand that triggered the First World War. So how did Russia’s hawkish leader, Vladimir Putin, respond to the battle cries of his people?

He signed a decree halting fruit and vegetable imports from Turkey, banning charter flights and the sale of package holidays, and scrapping Russia’s visa-free regime with the country. His proxies warned about possible escalation involving energy imports, while the media speculated about cyber-attacks (Moscow had used this tool to powerful effect on Estonia in 2007, Georgia during the 2008 war, and then against Ukraine as it annexed Crimea in 2014). The most important battleground of this conflict will not be the air or ground but rather the interconnected infrastructure of the global economy: disrupting trade and investment, international law, the internet, transport links, and the movement of people. Welcome to the connectivity wars.

This form of warfare is not uniquely Russian – quite the contrary. As Putin signed his sanctions decree, the Turkish government was holding a summit on refugees with the European Union. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has realised that the inflow of refugees to Europe changes his power dynamic with the EU. Using his ability to control the flow of migrants as a weapon, Erdogan has gone from being a supplicant for membership of the EU club to being a power player who can extract money and political favours.

The ease with which countries are weaponising the structures of the international system raises dark omens for the current world order

The EU is equally adept at instrumentalising economic interdependence for geopolitical ends. When Russia annexed Crimea, it did not send troops to defend Ukrainian territory. Instead it introduced an array of sanctions, including visa bans and asset freezes against targeted individuals, as well as commercial measures aimed at specific sectors of the Russian economy, such as the financing of energy exploration. The United Nations has also used sanctions for decades, and the United States has reshaped the very nature of financial warfare since it launched its War on Terror.

While sanctions are vastly preferable to conventional warfare in humanitarian terms, the ease with which countries are weaponising the structures of the international system raises dark omens for the current world order. In 1914, globalisation collapsed because the world’s most powerful nations went to war. A hundred years later, it is the reluctance of the great powers to engage in all-out war that could precipitate a new unravelling of the global economy.

Some may say that this is an exaggeration: sanctions have been with us since the time of the Peloponnesian wars, and mercantilist behaviour is as old as the state. What is so dangerous about the phenomenon?

The short answer is: hyper-connectivity. During the Cold War, the global economy mirrored the global order – only limited links existed across the Iron Curtain, and the embryonic internet was used only by the US government and universities. But with the collapse of the Soviet Union, a divided world living in the shadow of nuclear war gave way to a world of interconnection and interdependence. Some hailed the end of history. The world was largely united in pursuing the benefits of globalisation. There was talk of win-win development as Western multinationals made record profits and emerging economies boomed. Trading, investment, communications, and other links between states mushroomed. And these interstate links have been amplified further by the ties between people powered by technology: by 2020, 80 percent of the planet’s population will have smartphones with the processing power of yesterday’s supercomputers.[1] Almost all of humanity will be connected into a single network.

Interdependence, once heralded as a barrier to conflict, has turned into a currency of power, as countries try to exploit the asymmetries in their relations

But, contrary to what many hoped and some believed, this burgeoning of connections between countries has not buried the tensions between them. The power struggles of the geopolitical era persist, but in a new form. In fact, the very things that connected the world are now being used as weapons – what brought us together – is now driving us apart. Stopping short of nuclear war, and not prepared to lose access to the spoils of globalisation, states are instead trying to weaponise the global system itself by utilising the disruption of various links and connections as a weapon. Mutually Assured Disruption is the new MAD.

Interdependence, once heralded as a barrier to conflict, has turned into a currency of power, as countries try to exploit the asymmetries in their relations. Many have understood that the trick is to make your competitors more dependent on you than you are on them – and then use that dependency to manipulate their behaviour.

Like when a marriage goes wrong, it is the innumerable links and dependencies that make any war of the roses effective – and painful. Many of the tools look familiar to those employed during the globalisation of the 1990s, but their purpose is different.

The global trading regime, once a tool of integration, has been riven by economic and financial sanctions. Likewise, global multilateral institutions are increasingly sidelined by a new generation of competing friendship clubs. Rather than using infrastructure and the construction of physical infrastructure links as a way to maximise profits, China and the US are using them as a tool for power projection. And even the internet is being used as a weapon, and fragmented because of concerns about privacy and security.

This means that countries that do not depend too much on any single other country (with a diversified economy; able to import energy from many places) will be shielded from most geo-economic attacks. Few countries will follow North Korea into a world of autarchy – but reacting to the exploitation of interdependences, they will try to carve out spheres of independence. The US is on a quest for energy independence; China is shifting towards domestic consumption, diversifying its foreign holdings away from the dollar and developing an alternative to the SWIFT payment system; Russia is building pipelines to Asia to lessen its dependence on European markets.

The new battlegrounds: Three domains of disruption

When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, a new wall was erected between the management of the global economy and the battles of geopolitics. The economy was pure business, and foreign policy focused on managing geopolitical crises in parts of the world that are economically marginal.

But the reality is that in today’s world, all parts of the global system are ripe for disruption, be they economic, political, physical, or virtual. The wall between economics and politics has fallen, and political conflicts are fought through the system that manages the global economy.

Economic warfare

First, economic warfare. All types of economic activity – trade, access to finance, and investment – are being used as weapons and tools of disruption. Faced with war-weary publics and tightening budgets, Western powers are projecting power through their influence over the global economy, finance (including the dollar and euro), and trade, and through their control over multinational corporations domiciled in their countries. As British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond recently said: “There is a question about whether the EU – which does not have and won’t have a military capability – wants to develop a genuinely powerful alternative source of strategic power in the sanctions weapon.”

For the Obama administration, ever more sophisticated financial sanctions are the new drones – offering devastating effective and allegedly surgical interventions without running the risks of sending in ground troops.[2] Non-Western countries also impose sanctions, though these usually aren’t called sanctions and are sometimes disguised as stricter sanitary controls or customs-related delays: Russia has introduced sanctions on Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine to prevent their drift Westwards; Turkey is sanctioning Syria and blockading Armenia; and China has used sanctions against Japan and the Philippines over maritime disputes.[3]

Sanctions disrupt and distort global trade, and can hurt domestic businesses as well as their targets. US companies have had to stay away from Iran, while sanctions on Russia have hurt German businesses forced to reduce their exports to the country (58 percent of German firms have been negatively affected by the sanctions[4]), and French shipyards, which have suffered through the cancellation of the sale of Mistral ships. They can also provoke counter-measures. In 2014, Moscow retaliated against Western measures by banning food imports from the countries that had joined sanctions against it.

Governments also tap into their populations’ spending power and incite public boycotts. Turkey used this tactic in 1998 and 2001 after the Italian and French governments recognised the mass killings of Armenians as genocide. Beijing encouraged public boycotts of Japanese goods in 2005 as a response to the Japanese prime minister’s visit to a controversial shrine honouring the empire’s war dead, and against France in 2008 after anti-China protests disrupted the Olympic torch relay in Paris. And states are not the only relevant actors in this new world disorder: civil society campaigns to pressure investors to pull their money from targeted industries – such as fossil fuels, tobacco, and arms – have a significant impact.[5]

This economic warfare is turbo-charged as states return to or continue to use the tactics that globalisation tried to leave behind, manipulating currencies, and deploying regulations and subsidies to disadvantage foreign competitors. The fact that the success of the BRICS has been widely attributed to their willingness to intervene in the market has encouraged policies of “state capitalism” worldwide, which could lead to a nominally open but increasingly bastardised world trade system.

Another kind of economic coercion is on display in efforts to weaponise migration flows. Erdogan is only the most recent leader to use their ability to direct population flows as a tool against rivals. There have been more than 75 attempts by state and non-state actors to use population movements as political weapons since the 1950s. Leaders from Muammar Gaddafi to Slobodan Milosevic have threatened to displace or expel groups, demanding financial aid, political recognition, or an end to military intervention.

This economic warfare is likely to include the retreat from globalisation of countries and companies alike. Trying to shelter themselves from disruption, they further distort the market. It is not only countries with reason to fear that they will be targeted by sanctions that are hedging; the hyper-connectedness of the global market means that many fear that they are vulnerable to ripple effects. This has caused a global push to decrease vulnerabilities and interdependence. India, for example, has been trying to diversify its energy suppliers since the UN Security Council imposed sanctions on Iran. The rush to decrease dependencies may be sound for individual countries, but it leads to economic inefficiencies and reduces the economic benefits of globalisation.

Weaponising institutions

The second battleground is the weaponisation of international institutions. Optimists had hoped that global trade relations would help socialise rising powers such as Russia and China into “responsible stakeholders” in a single global system under shared laws and norms. But multilateral integration at times seems to be a source of division rather than unity.

Some countries undermine the international system by gridlocking institutions or pushing for a selective application of the rules. Emerging powers such as India, Russia, and China have sought to frustrate the established powers by disrupting their use of existing institutions – from the WTO’s Doha Round of trade talks, to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) on election observation. They claim – although this is contested in Western capitals – that this has been mirrored by the United States and its allies, which have increasingly sought exceptions from the rules for themselves. For example, Washington calls on other countries to abide by the law of the sea, although it has not itself ratified the relevant UN convention. The EU and the US talk about the inviolability of borders and national sovereignty, but tried to change both norms through their intervention in Kosovo (which they tried to retroactively legitimate by coining the “responsibility to protect”).

There is a global trend towards forming competing, exclusive “mini-lateral” groupings, rather than inclusive, universal multilateral projects. These groupings, bound by common values – or at least common enmities – are made up of like-minded countries at similar levels of development. The “world without the West” groupings include the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), and a host of sub-regional bodies. China is working to promote parallel institutions – such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) – some of which complement the existing order and some of which compete with it. Meanwhile, the West is also creating new groupings outside the universal institutions – such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in Asia and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) – that exclude China and Russia. Hillary Clinton referred to TTIP as an “economic NATO”[6] while President Barack Obama, speaking about the TPP, declared “We can’t let countries like China write the rules of the global economy. We should write those rules”.[7]

As the world grows increasingly multipolar, smaller states find themselves forced to choose between competing great powers’ spheres of influence, as major regional powers strengthen themselves at the expense of the periphery. Look at Russia’s relationship with its “near abroad”, Germany’s role in Europe, and China’s posture in Asia. All three have economic as well as diplomatic and security consequences. Chinese institutions are not really multilateral institutions which give states representation in binding institutions, but rather a cover for a series of bilateral relationships between smaller countries and a powerful Beijing. Russia’s “near abroad” policy does not reduce its neighbouring countries to vassal states, as some claim, but it does try to use asymmetries in the relationship to bind them into a Russian system. Competition between rival projects can spill into conflict; the Ukraine crisis came about because of a clash between two incompatible projects of multilateral integration — the European-led Eastern Partnership and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

International law was intended to be a way of de-escalating disputes between countries, but analysts are also speaking about its use as a weapon against hostile countries – “lawfare”. The multilateral institutions that were supposed to be the benign invigilators of a new era of win-win cooperation are becoming a battleground for geopolitical competition.

Infrastructure competition

The third battleground is competition through the infrastructure of globalisation – both physical and virtual.

Countries have learned that, if they cannot be independent, the next best thing is to make their partners more dependent on them than the reverse. If all roads lead to Rome, they are best served by becoming Rome. This quest for “asymmetric independence” is encouraging leading regional powers – Russia, China, Germany, Brazil, South Africa, and Nigeria – to try to entrench their role as core economies, reducing neighbouring countries to the status of periphery.

Transport infrastructure is a key weapon in this fight, and China is leading in its use. In 2013, President Xi Jinping announced the “One Belt, One Road” project, intended to link China to cities as far as Bangkok and Budapest, and develop the Eurasian coast. This is just one example of the infrastructure projects aimed at exporting China’s surplus capacity while expanding its access to raw materials and export markets.

This approach to regional integration differs from ASEAN-style or EU-style regionalism. Rather than using multilateral treaties to liberalise markets, China promises to facilitate prosperity by linking countries to its continuing growth through hard infrastructure such as railways, highways, ports, pipelines, industrial parks, border customs facilities, and special trade zones; and soft infrastructure such as development finance, trade and investment agreements, and multilateral cooperation forums.

The establishment of new links may at first glance not appear like a disruption, quite the opposite. But China’s “One Belt, One Road” project creates dependencies that can then be exploited, while it also bypasses certain countries. It will be a core-to-periphery structure of connectivity, regional decision-making, and membership status, a hub (Beijing) and spokes (other countries) arrangement. The practice of reciprocity between the core and the periphery will be that if others respect China, China will reciprocate with material benefits; but if they do not, China will find ways to punish them. China’s infrastructure projects could be as important to the twenty-first century as the US’s protection of sea lanes was to the twentieth.

If transport links are the hardware of globalisation, the internet is its software. Like physical infrastructure links, the virtual infrastructure of the internet is also being weaponised by states competing for power. As a result, rather than being the global public square “wholly indifferent to international boundaries” it was once thought to be, the internet is splintering along national lines. Putin might have offered Edward Snowden refuge, but it is Washington’s closest allies – such as Chancellor Angela Merkel in Germany and President Dilma Rousseff in Brazil – who are the most concerned about the US prying into their citizens’ private lives. Countries such as Australia, France, South Korea, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia and Vietnam have already moved to keep certain types of data on servers within their national borders. Deutsche Telekom has suggested a German-only “Internetz”, while the EU is considering a virtual Schengen area.

The New G7: The geo-economic playerse and their powers

In the new age of geo-economics, some countries and regional blocs will do well, and some will suffer. The US dominates on several fronts, but other players exert considerable influence in their respective niches. We have identified seven archetypal forms of power in the world of geo-economics, a new G7.

The financial superpower: The US

The US remains the world’s sole superpower and can still project military might with greater ease than any other country. But recently it has been using the role of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency to develop a new type of instrument for projecting power. After 9/11, when the president declared a global “War on Terror”, officials in the US Treasury started exploring how Washington could leverage the ubiquity of the dollar and US dominance of the international financial system to target the financing of terrorism. What started as a war against al-Qaeda grew to encompass measures against North Korea, Iran, Sudan, and even Russia. The enormous fines imposed on banks accused of breaking the sanctions – such as France’s BNP Paribas – sent shockwaves through global financial markets and acted as a powerful deterrent to future deals. In the words of the then-CIA director Michael Hayden, “this was a twenty-first-century precision-guided munition”.[8]

The regulatory superpower: The EU

Because the EU has the world’s largest single market, most multinational companies depend on access to the region – which means complying with EU standards. The Union has used this power at various times over the years in the economic realm – blocking the merger of General Electric and Honeywell, forcing Microsoft to unbundle its Explorer browser, and challenging US agri-business in Africa and other global markets over the use of genetically modified organisms. This export of regulations has extended into the political sphere on issues such as climate change – and most dramatically through the EU’s accession process and neighbourhood policy.

These policies make access to EU markets and membership conditional on other countries adopting EU legislation and EU standards. To join the Union, candidates need to integrate over 80,000 pages of law – governing everything from gay rights and the death penalty to lawnmower sound emissions and food safety – into domestic legislation. What is more, regulatory power is less costly, more durable, more deployable, and less easily undermined by competitors than more traditional foreign policy tools.

The construction superpower: China

China today is using economic statecraft more frequently, more assertively, and in more diverse fashion than ever before. Even though China’s trade and economic power is growing, its most innovative geo-economic tool is infrastructure – both physical and institutional. Stretching from Hungary to Indonesia, Beijing’s budget for the AIIB is $100 billion – as much as the Marshall Plan spent in Europe, in inflation-adjusted dollars – which mostly goes to finance roads, railways, pipelines, and other infrastructure across Eurasia, smoothing China’s westward projection. Chinese sources claim it will add $2.5 trillion to China’s trade in the next decade, more than the value of its exports in 2013, when it was the world’s top exporter.

In addition, while Beijing remains an active player within existing international institutions, it is also promoting and financing parallel structures such as the AIIB and the SCO. The overall goal of these efforts is greater autonomy, primarily from the US, and an expansion of the Chinese sphere of influence in Asia and beyond.

China’s ambitions go beyond the physical to the virtual world where it is pushing a cyber-sovereignty agenda, challenging the multi-stakeholder, open model for internet governance defended by the US, to allow national governments to control data flows and control the internet within their jurisdiction. And the Chinese leadership is increasingly strengthening its control over the internet and technology suppliers. With the largest community of netizens (Nearly 700 million Chinese citizens now use the internet regularly, some 600 million of them through mobile devices), China has weight.

The migration superpower: Turkey

In an age of mass migration, the ability to control flows of people is a source of power. The Turkish authorities used the threat of people flows to change the balance of power between them and the EU – demanding the lifting of visa restrictions, financial aid to mitigate the burden of hosting more than two million Syrians, and the reinvigoration of their EU membership bid.

The spoiler superpower: Russia

As its empire receded after the end of the Cold War, Russia turned itself into a pioneer of disruption. Its foreign policy of the last few years has successfully shaped the behaviour of its neighbours and other powers through tactics including gas cut-offs, sanctions, expelling workers, cyber-attacks, disinformation and propaganda campaigns, and attempts to gridlock Western-led international organisations from the UN to the OSCE. In parallel, it has worked to establish new organisations to extend its power, such as the BRICS, the SCO and the EEU. But because Russia has not done enough to strengthen and diversify its economy – which relies overwhelmingly on hydrocarbon exports – its share of the global economy has been on a downward trajectory. This will limit its ability to act as a spoiler over time.

The energy superpower: Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s geo-economic power rests on the 10 million barrels of oil it extracts every day, and it is now responsible for a fifth of the global oil trade. For decades it has converted its hydrocarbons into economic and geopolitical power, fostering the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) as the primary instrument for translating market power into broader international economic leverage. It has used its willingness to take short-term hits to shape global markets to its advantage (and to the disadvantage of rivals such as the Iranian or US shale companies). What’s more it has been willing to invest billions of petro-dollars in support of its foreign policy goals – supporting counter-revolutionary regimes during the Arab uprisings as well as waging a regional proxy war against Iran.

The people’s power

The connected economy and society is much more vulnerable to disruptions from below – whether incited by hostile governments, terrorist groups or teenagers in their bedrooms. And the ability of people to cluster on the web – in imagined majorities – makes both democratic and autocratic politics more volatile and prone to campaigns against particular courses of action (Francis Fukuyama has talked about the birth of a vetocracy as skittish leaders bend to public pressure). Hacking, public boycotts and disinvestment campaigns – whether autonomous or staged by governments – are becoming more common, more effective, and take less time and less resources to stand up.

Where does this leave Europe?

In theory, the EU should fare better in a geo-economic world than a classic geopolitical one. Economically, the EU is a giant. It sits at the heart of a eurosphere of 80 countries that depend on it for trade and investment, and even align themselves with its currency. It is a regulatory superpower. What’s more, some of its leading member states – such as Germany, the world’s foremost export nation – are particularly well-suited to wield power in a geo-economic world.

However, there are questions about how durable Europe’s geo-economic power is. As its share of the global economy shrinks, how long will its regulatory power last? And will the EU – which, unlike the other great powers, is not a state – be able to overcome its structural divisions and pool its ample resources behind common policies? Much of its foreign policy depends on unanimous support from all 28 member states – which have divergent views and different levels of vulnerability to blowback. For example, while Russia doesn’t even appear in the list of the most important trading partners of Portugal, over 17 percent of Estonia’s exports go towards the east, as Sebastian Dullien explains.

But most importantly, Europe is hobbled by the fact that, more than any other power, its inhabitants live at the “end of history”, subscribing to the ideological orthodoxies of “win-win” globalisation. Many of its governments still think the economy should be protected from politics and geopolitics and that inter-state conflict can be avoided through integration and interdependence, and have faith in the ability of institutions to “socialise” the rising powers.

To counter these disadvantages, European states need to realise that – in the face of geo-economic challenges from other powers – state intervention can be the best way to promote an open global economy. For example, Western countries could learn from China’s infrastructure-first model, but adapt it to their strengths. They should also develop ways of compensating member states that lose out from particular geo-economic policies, so that they can more effectively wield their collective power. They need – at both a national and an EU level – to set up a machinery for economic statecraft similar to that of other great powers. The European Union should develop an economic statecraft taskforce and a sanctions bureau to co-ordinate this increasingly powerful tool.

Above all, Europeans should be at the forefront of the movement to develop the rules of engagement for economic warfare. When governments use the infrastructure of the global economy to pursue political goals, they challenge the universality of the system and make it more likely that other powers will hedge against this disruption. They can also provoke retaliation. In the same way that states have developed a series of agreements and conventions that govern the conduct of conventional wars between countries, principles of conduct must be applied to the economic arena. Of course, this kind of coordination will prove difficult, given the wariness of all-out conventional war that makes economic disruption so attractive and widespread in the first place.

As part of this movement, Europeans should encourage their businesses to become stronger advocates for trade liberalisation and foreign investment in the Global South. More than anyone else, Europeans have an interest in developing more political, regional and creative forms of collective action to fight the spirit of atomisation that is increasingly defining the world.

[1] http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21645180-smartphone-ubiquitous-addictive-and-transformative-planet-phones

[2]Although of course Obama did not invent them. Juan Zarate’s book is called “Treasury’s War” and he described a new kind of warfare that “involves the use of financial tools, pressure and market forces to leverage the banking sector, private-sector interests, and foreign partners in order to isolate rogue actors from the international financial and commercial systems and eliminate their funding sources.”

[3]When the Japanese government purchased three of the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in September 2012, Japanese workers suddenly had difficulties to obtain working visas and companies with investments in China were experiencing delays in gaining regulatory approval. Following the western sanctions, Russian health and safety authorities closed several McDonald’s restaurants in Moscow.

[4]http://russland.ahk.de/uploads/media/2014_12-18_Umfrage_Sanktionsauswirkungen_Auswertung_Presse_de.pdf

[5]The fossil fuel divestment campaign for instance which started only three years ago has caused the disinvestment by 400 institutions and over 2000 ‘ultra-high net worth individuals’ that together hold $2.6 trillion in assets. (Numbers given by the campaign.)

[6]https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/david-ignatius-a-free-trade-agreement-with-europe/2012/12/05/7880b6b2-3f02-11e2-bca3-aadc9b7e29c5_story.html

[7]https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/10/05/statement-president-trans-pacific-partnership

[8]Juan Zarate – Treasury’s War (2013), p. 244.

This essay is part of the Rethink:Europe project, a joint initiative by ECFR and Stiftung Mercator.

Pictures credits: Header: Zephyris / Wikimedia; Euros: Flickr / Hernan Piñera;

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.