What will be the consequences of the Russian currency crisis?

Russia severe currency crisis finds the government totally unprepared and will likely bring a sharp diminution in people's income

The collapse of the rouble at the end of 2014 was obviously triggered by the drop in the price of oil. However, the Russian currency has weakened to a significantly greater degree than any other currency in the world, even the currencies of other oil-dependent economies. In just one month, between 18 November and 18 December, the rouble fell by 43 percent. This provoked two waves of runs on the banks and led to general consumer panic. Therefore, what is happening in Russia is a genuine currency crisis. What were the causes of this crisis and what will happen next?

The crisis was enabled by three types of factors – market factors, political factors, and structural factors.

The Russian economy’s structural problems were already becoming apparent in 2012. Oil prices reached historic highs in 2011 and stayed close to them until the third quarter of 2014. However, the Russian economy’s reaction to this export-driven windfall was very different from that in other periods, either in the period of economic boom between 2004 and 2008 or in the period of post-crisis recovery from 2010 to 2011.

The crisis was enabled by three types of factors – market factors, political factors, and structural factors.

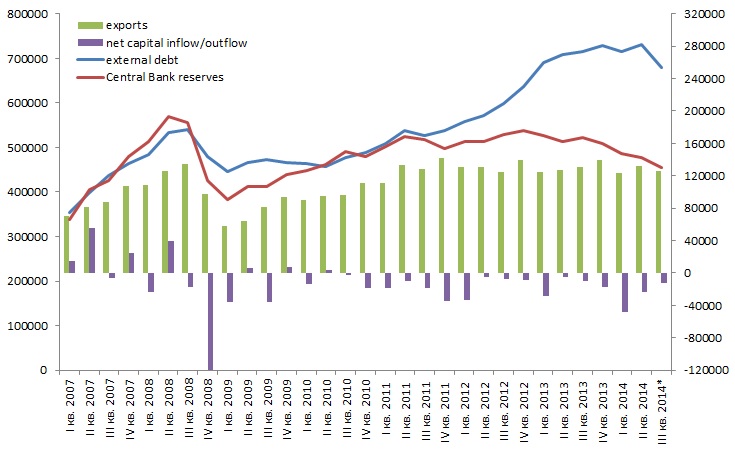

In the second half of 2011, Russia’s Central Bank reserves stopped growing. This meant that there was no extra demand for roubles from exporters or investors (through the sale of hard currency). Between 2011 and 2013, net capital outflow amounted to $196.2 billion. At the same time, Russian companies and banks continued to borrow from abroad: in 2012–2013, Russian external debt increased by $190 billion, and in January 2014, it had reached $728 billion. This fact partly reflects the current business model in the Russian economy: companies prefer to keep their profits abroad, while they support their operations within Russia through borrowing. This kind of debt financing is used to hedge against the risk of expropriation by the state. In general, this dynamic showed that the market has no great faith in the future of the Russian economy.

The dynamics of Central Bank reserves and total Russian debt (left-hand scale), Russian exports and net capital outflow (right-hand scale), $m

Source: Central Bank of Russia

Source: Central Bank of Russia

In 2012, when oil prices stopped rising and the economy returned to pre-crisis levels, investment growth and the economy as a whole abruptly slowed. This growth model driven by rising consumption (financed by increasing export revenue) stopped working. As a result, in 2013 the economy’s growth rate, at 1.3 percent, was significantly lower than that of the global economy and the average growth rate of CIS countries.

In 2013 the Central Bank announced that it was moving towards an inflation targeting policy. This basically meant that the bank intended to intervene less in setting exchange rates, concentrating primarily on the inflation rate target. Taking this under conditions of steady exports and growing net capital outflow led to the wholesale devaluation of the rouble. However, the devaluation helped the economy: while in 2013 industrial growth slowed to under 1 percent by the first half of 2014 it had bounced back to 2.5 percent, fuelled almost entirely by the dynamics of the manufacturing sector.

But the heightened political tensions caused by the conflict in Ukraine and the sharp deterioration in relations with the West have reinforced the scepticism of the markets about the future of the Russian economy. The annexation of Crimea and the ongoing conflict in eastern Ukraine led to a fall in the stock market and increased pressure on the rouble. The Central Bank was forced to prop up the rouble and spent $45 billion on supporting the currency between January and the end of September 2014.

The conflict in Ukraine and the sharp deterioration in relations with the West have reinforced the scepticism of the markets about the future of the Russian economy

The watershed moment was the imposition of the third round of Western sanctions, which cut Russian companies off from the world’s financial markets. Along with falling oil prices (a key market factor), this caused market players to reassess the risks. Before the introduction of sanctions, the ratio of external debt to foreign exchange reserves (at 1.4) was not particularly worrying. But the fact that companies could no longer refinance their debt on external markets necessitated a rethink. It became clear that, with export revenues falling because of lower oil prices, companies would accumulate excess currency in their accounts. The supply of currency in the market from exporters (many of whom also had large debts) declined sharply, while demand from the debtor companies increased.

In October 2014 the Central Bank was forced to spend another $26 billion to support the rouble. After that, preserving the country’s reserves became the priority, so in November, the bank’s intervention fell to $10 billion. So everything was in place for a currency crisis and this is why the Russian Minister for the Economy called it “the perfect storm”. The storm was only halted by a sharp increase in the Central Bank’s interest rate and by informal pressure on companies that brought about a speedy decline in foreign exchange trading.

Future developments in the foreign exchange market will depend on the price of oil. If oil prices keep falling, tension in the market will increase again. However, the weeks before and after the New Year holidays will be used to prevent a looming banking crisis caused by the interest rate being at 17 percent.

As for the economy in general, the crisis will spread through a sharp increase in the price of imports in roubles and the associated price shock for consumers.

Russia’s annual volume of imports of goods comes to around $340 billion, while the size of the entire Russian retail market comes to around $750 billion. According to Russian State Statistical Service, 40 percent of goods are for consumption, 40 percent are intermediate goods and the rest is machines and equipment. The share of imports in the consumer market is around 30–40 percent. A very important role is played by intermediate imports (components and raw materials used in domestic production), so their increase in rouble price will affect a large range of products. Moreover, while loans become less accessible, companies will be obliged to pass on the increased costs of production to consumers.

So the double devaluation of the rouble will be felt in rising price and shrinking consumption. According to the Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy, this will add at least 10–12 percentage points to normal inflation, which will reach 15-20 percent. Import substitution options are relatively limited: large-scale import substitution would require significant investment and, at the moment, the resources for this are not there. And a fall in consumption (as a result of the falling purchasing power of households) will cause a decline in production.

According to the Central Bank’s December forecast, GDP in 2015 may fall by 4.5–4.8 percent. This is what the bank calls a “stress scenario”, and it assumes that the oil price will stay at $60 a barrel and Western sanctions will remain in place. In fact, this scenario seems to be the most realistic; any other scenario would involve either the lifting of sanctions or a rise in the oil price to $80 or even $100.

The Russian government was clearly totally unprepared for such a sharp fall in the oil price and for the mayhem on the currency markets.

The Russian government was clearly totally unprepared for such a sharp fall in the oil price and for the mayhem on the currency markets. It is only now beginning to think about anti-crisis measures. This was very clear from President Vladimir Putin’s annual press conference on 18 December. The president did little more than express his conviction that oil prices will start to rise again in the next two years, boosting economic growth. This means that he is not yet ready to discuss options for a major adjustment of his model of crony state capitalism.

At the beginning of 2015, the government will have to balance between the desire to stimulate consumption and the danger of runaway inflation. In any case, this crisis – which to some extent is a sequel and completion of the previous crisis in 2008-2009 – will bring about a painful diminution in people’s income.

Kirill Rogov is Senior Researcher at the Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy, Moscow.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.