Israeli elections primer: What to look out for

For the first time this century the leader of Israel’s Labour Party appears to be genuinely competing for the position of Prime Minister.

For the first time this century the leader of Israel’s Labour Party appears to be genuinely competing for the position of Prime Minister. In every election since Ehud Barak’s victory in 1999 the Labour Party has faced a double digit Knesset seat deficit in comparison to the winning party. When Netanyahu called for early elections the expectation was that the elections would again centre around what kind of a coalition he would form, much as was the case in 2013. After all, it was Netanyahu’s decision to go back to the voters after only two years.

What has emerged in the course of the campaign is threatening to become a perfect storm that could leave Israel’s second-longest serving Prime Minister out in the cold. While Netanyahu still remains favourite to be best positioned to form a coalition, momentum is with the “anyone but Bibi” camp.

The first shaping event of this election was the early alliance formed between Labour and the centrist party, Hatnuah, of Tzipi Livni (former Kadima party leader, outgoing justice minister in the old Netanyahu coalition, and chief peace negotiator). The combined list – known as the Zionist camp – immediately created a near parity between itself and Netanyahu’s Likud list. And while neither comes close to even winning a quarter of the Knesset’s seats, let alone a majority, they now seem to be competing over who will be the biggest party and take the lead in forming a new governing coalition.

In recent days a gap has emerged in polls in favour of the Zionist camp. The elusive momentum factor is with Zionist Camp candidate Isaac Herzog, and that can be attributed to a few factors.

First, for Netanyahu national security was the ideal fighting terrain for this election, while his opposition prefer a focus on Israel’s domestic socio-economic woes and fading international standing. Netanyahu has not been helped by State Commissioner reports published during the campaign, both on improprieties in the management and expenditures of his own household and on the longstanding housing crisis which has contributed to squeezing the middle class and worsened growing inequality and struggles for Israel’s working poor.

Netanyahu seemed well positioned to reassert security as the lead election item when Israel’s northern border saw a flare up and regional turmoil continued unabated as the Prime Minister played what seemed to be a trump card of putting the Iranian threat centre stage with his speech before the US Congress and its headline coverage. However, Netanyahu appears to have overreached in trying to impose this national security agenda. His comment that the housing crisis was important, but that first one needed to worry about staying alive in the shadow of the existential threat posed by Iran, for instance, did not go down well. The speech before Congress appears to have only given Netanyahu the most ephemeral of bumps in the polls. Meanwhile, Herzog has not quite managed to establish his own national security agenda, he has reached a bar of acceptability on that front for enough of Israel’s voters.

In fact, a number of former security establishment heavy weights, led by Former Mossad chiefs Meir Dagan and Shabtai Shavit, have come out in force opposing the incumbent Prime Minister’s policies in the national security arena and especially his mismanagement of the American relationship, his excessive scaremongering, and his lack of diplomatic initiative.

What is more, in this election traditional Likud voters are being offered an easy alternative to the original Likud brand with the formation of a party led by former Likud Minister Moshe Kahlon – known as the Kulanu party. Going over to Kahlon will be a simpler ask for many Likud voters than supporting either Labour or the Yesh Atid party of Yair Lapid, identified with the old Ashkenazi liberal elite. Kahlon is branding himself as the soft-Likud or real-Likud just a few centimetres to the centre of the now more right-wing brand.

“Anyone but Bibi” has gained popularity as a brand. There appears to be a pervasive atmosphere of having had enough of the man at the top. This has been helped by a media environment that is hostile to Netanyahu, in many respects more personally than ideologically. The damage that the mass circulation free newspaper established by Netanyahu and US Republican backer and casino billionaire Sheldon Adelson has wrought upon the rest of the print market has lent commercial incentive to much of the media in attacking Netanyahu.

But Netanyahu and the Likud have also simply run a bad campaign. Some things like the State Comptroller reports have worked against them. But the Likud campaign has mostly scored own goals. Many of Likud’s leading next generation figures have withdrawn from politics and there have been a number of campaign missteps, in particular an advert that appears to compare much maligned Israeli workers to Hamas terrorists. Some of the efforts at rebranding the Netanyahu couple as likeable have bordered on the grotesque. Overall the Likud camp and campaign has appeared lacklustre and downhearted.

The possible Herzog candidacy for the premiership has emerged as a focal point for the “anyone but Bibi” camp. Herzog has not become Mr Popular, still trails Netanyahu in the preference for Prime Minister surveys, and has hardly set the world alight with his own campaign, or indeed with his policy ideas. But he has established a sense of being equal in competing for the top post. It will only become clear on Tuesday whether Herzog has sealed the deal with enough of the electorate and whether Netanyahu has become a liability rather than an asset for the Likud. If he falls, the post-mortem will be all about how badly Netanyahu misjudged in calling this early poll.

Yet given the perfect storm it might be more remarkable that Herzog is still the under-dog.

Coalition options

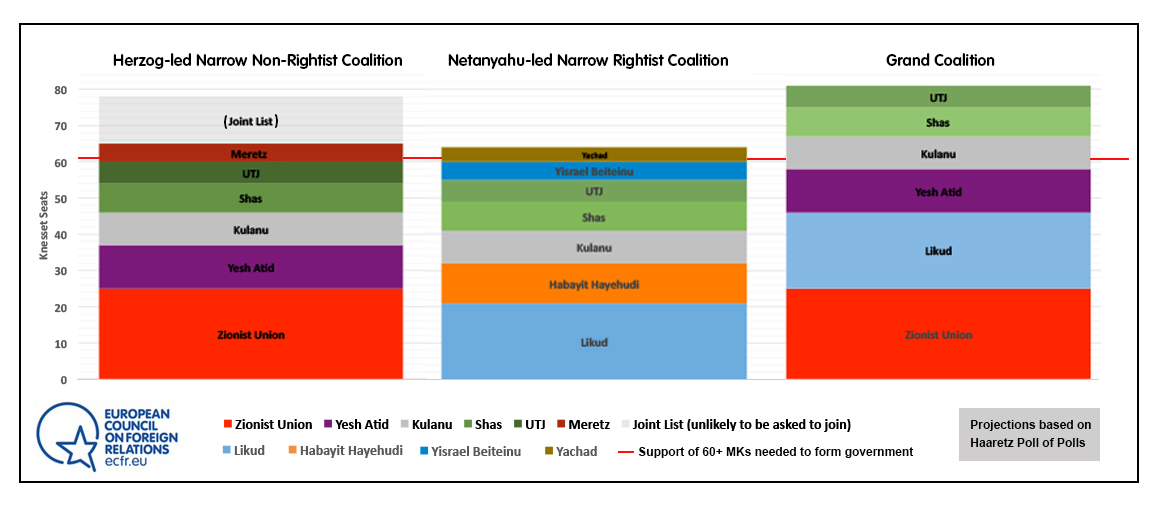

If the polling numbers more or less hold up then it could prove extremely tricky for any candidate to stitch together a functioning government. Three principle variations on coalition composition suggest themselves.

1. A Netanyahu-led narrow, rightist government. This would see the Prime Minister stay in power with his more natural right-wing and religious allies forming a governing block with the Jewish Home Party of Naftali Bennett, the party of outgoing Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, albeit a much diminished force, with the traditional ultra-Orthodox parties of Shas and the United Torah Judaism.

But to get a majority of 61 seats, Netanyahu would also have to win over his former Likud colleague and now rival, Moshe Kahlon. It would be a prospect Kahlon is not enthusiastic about, and would likely exacerbate many of Israel’s problems with the international community, including with Israel’s closest allies. It would pose Bibi the challenge of governing from the far right, rather than having fig-leaf allies from the centre to give acceptable cover to his policies. Netanyahu might expand the coalition by trying to woo Yair Lapid, leader and founder of the centrist Yesh Atid party, although that is unlikely. He might also try to enlist the ultra-rightist Yachad Party, led by Shas-breakaway Eli Yishai, although he and Aryeh Deri, leader of the ultra-Orthodox Shas (from which Yachad split) will make for very prickly bedfellows.

2. A Herzog-led narrow, non-rightist coalition. This still looks extremely tricky and perhaps impossibly heterogeneous cobble. If Herzog and his potential allies were willing to work with the joint Arab List (a joint list of the three parties that have garnered the Palestinian-Israeli vote in recent elections, currently getting at least a dozen seats in the polls) whether as a formal part of a coalition or supporting the government with a set of understandings from the outside (a kind of confidence and supply arrangement) then the task would be easier. But the parties supported by the Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel have been traditionally deemed unworthy coalition partners (a real Achilles heel of Israeli democracy and its lack of inclusivity). Barring an arrangement with the Joint Arab List, Herzog would somehow have to bring together the centrist Yair Lapid and his anti-clerical bent together with the ultra-Orthodox and the soft right of Moshe Kahlon, together with the secular party Meretz (or, alternatively, Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu party). The Zionist camp, Lapid, Meretz, Kahlon, Shas, and United Torah Judaism together would pass the 61 coalition threshold but it would be a remarkable feat to pull off. Only if Herzog can build around a 4-plus seat margin over Likud, might it give the sense of a popular mandate to form such a coalition and to persuade the constituent parts to sign up.

3. A Grand Coalition. The third and perhaps most likely option is a national unity coalition. That would see a coalition based around the Likud and Zionist camp, most likely led by Netanyahu although possibly on the basis of a rotation. The coalition numbers would then be filled out by a combination of Lapid, Kahlon and perhaps Lieberman and/or ultra-Orthodox. Labour would insist on excluding the Jewish Home and Yishai’s Kahanists, while Likud would make the same demand vis-à-vis Meretz. The Joint Arab List would likely be excluded from all sides. But even a grand coalition would be a hard sell within the respective Likud and Labour movements.

Further complicating the coalition puzzle is a new rule whereby the threshold for entering parliament has been raised from 2 percent to 3.25 percent, which translates into a minimum of four seats for any faction to enter the Knesset. There are three parties running in this election that are hovering precariously close to that four-seat margin (Meretz left Zionist party, Yachad extreme right party and the Yisrael Beiteinu party of Avigdor Lieberman). Should any of them fail to meet the bar then this would be seats lost to the camp to which they belong and would tilt the balance in what is already set to be a very tight Knesset race.

There are some additional outlier possibilities. The two worth mentioning are a push within the Likud against Netanyahu, to keep the Likud in power without him – although the mechanism for doing that speedily would be challenging. The other is for the centrists to band together (Lapid and Kahlon – perhaps also with Lieberman) and to stake their own claim for leadership. Combined, they could well have the most seats and could refuse to serve in anyone else’s government. So far this has been ruled out, but what is said pre-election does not always hold true the morning after.

What is at stake in the election?

Much will depend on which of the coalition options emerges. All of them will make something of a priority of kick-starting some domestic socio-economic initiatives, with an emphasis on housing. A narrow rightist coalition predictably would accelerate the democratic recession and lurch towards a more exclusionary vision of a Jewish state that has been witnessed in recent years. Whereas a narrow Herzog-led non-rightist government could be expected to do the opposite.

On the Palestinian front neither of the two main blocks have come up with anything resembling a coherent programmatic plan. Herzog has suggested he would work with the Egyptians to re-launch peace talks with the Palestinians. But the Zionist camp has also defined Israel’s problem as more one of image and reputation than the occupation itself and policy substance, which suggests more investment will be made in making Israel appear better rather than definitively grappling with the occupation issue itself. The choice would seem to be between a doubling down on existing settlement and occupation policy, paralysis, or an attempt at some forward movement that would likely fall well short of a comprehensive deal and de-occupation. A centre-left government could pursue unilateral options alongside attempts at negotiations with the Palestinians and would likely be less provocative in the settlement arena, in withholding PA taxes, and in other punitive measures.

A more rightist government would see a clamour for some kind of further annexation of territory, though this is something that Netanyahu would likely want to resist. Under a continued Netanyahu premiership expect further international displeasure at irredentist policies, leading to more practical steps against settlements for instance (as Europe has been pursuing), albeit at a slow place. Nevertheless these do seem to affect the calculations of the Israeli public. If Herzog does become Prime Minister, the challenge for the international community will be to translate good will into meaningful change, something that Herzog’s government will not automatically embrace. And of course much will depend on what strategies the Palestinians themselves pursue.

On the most potentially explosive question of Gaza, none have presented a plan. But this might be one area where some progress can be made. Another Gaza war would put pressure on Israeli leaders to re-occupy Gaza, something they know is fraught with risks, but absent a change in policy that new round of violence is almost inevitable. So this is one arena outsiders should be actively pushing ideas. The biggest difference might be seen on the Iran question and how to handle that in the context of Israel’s relationship with America. A government that is somewhat split on the issue or Herzog-led would be less bellicose. That could stand in sharp contrast to the highly politically partisan way that Netanyahu has gone about his efforts to torpedo the negotiations.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.