European defence and the two per cent mantra

The best route to improved European defence capabilities is to build on the patchwork of co-operation that already exists – with Germany at its centre.

At the Munich Security Conference, the discussions over defence burden sharing took a predictable course. In 2014 NATO members agreed to increase their defence budgets to at least two per cent of GDP, to be reached over the coming decade. The Trump administration has been vocal in criticizing Europe’s ‘free-riding’ in the alliance, and US representatives in Munich were determined to once again make this spending pledge a central issue.

Burden-sharing across the Atlantic has long been a topic driven by the US, dating back to the Cold War. From the US perspective, allies should spend more and develop better military capabilities in order to support the US on global missions. These days those missions would most likely be in the Middle East, given Trump’s repeated promises to defeat ISIS.

Europeans, on the other hand, traditionally see NATO as an alliance for the defence of Europe itself. And NATO’s European members have long realized that they could do much to improve their capabilities by deepening co-operation between them. So when the US would call for greater spending, Europeans typically responded by proposing a ‘European pillar’ of the alliance, under which European members would co-ordinate their development and procurement processes and build an independent mission capability.

For Americans, of course, this would create an unwelcome challenge to US strategic leadership. Talk of a ‘European pillar’ therefore became an effective way for Europe to silence US complaints about free-riding.

But with President Trump’s obsession with getting a good ‘deal’ for America, calls for greater European spending have reached a new level. Decision-makers in Washington may finally be willing to accept the emergence of a European pillar, as long as they can demonstrate success in getting Europe to pay their fair share. And for the first time, a more sizable European contribution to NATO could become necessary to sustain US commitment to the alliance.

Angela Merkel has already recognized this, and confirmed her intention to meet the two per cent target over time. But effective defence spending is far more complex than percentages of GDP.

Spending smarter

In this fiscal year Germany's defence budget will grow by about 8 per cent. This is a faster rate than in recent years but will still not see Germany hit the two per cent goal any time soon. To do so would require an additional investment of between 25 and 30 billion euros each year and it is highly questionable whether Germany could spend such sums effectively. For smaller countries, of course, this problem is even more acute.

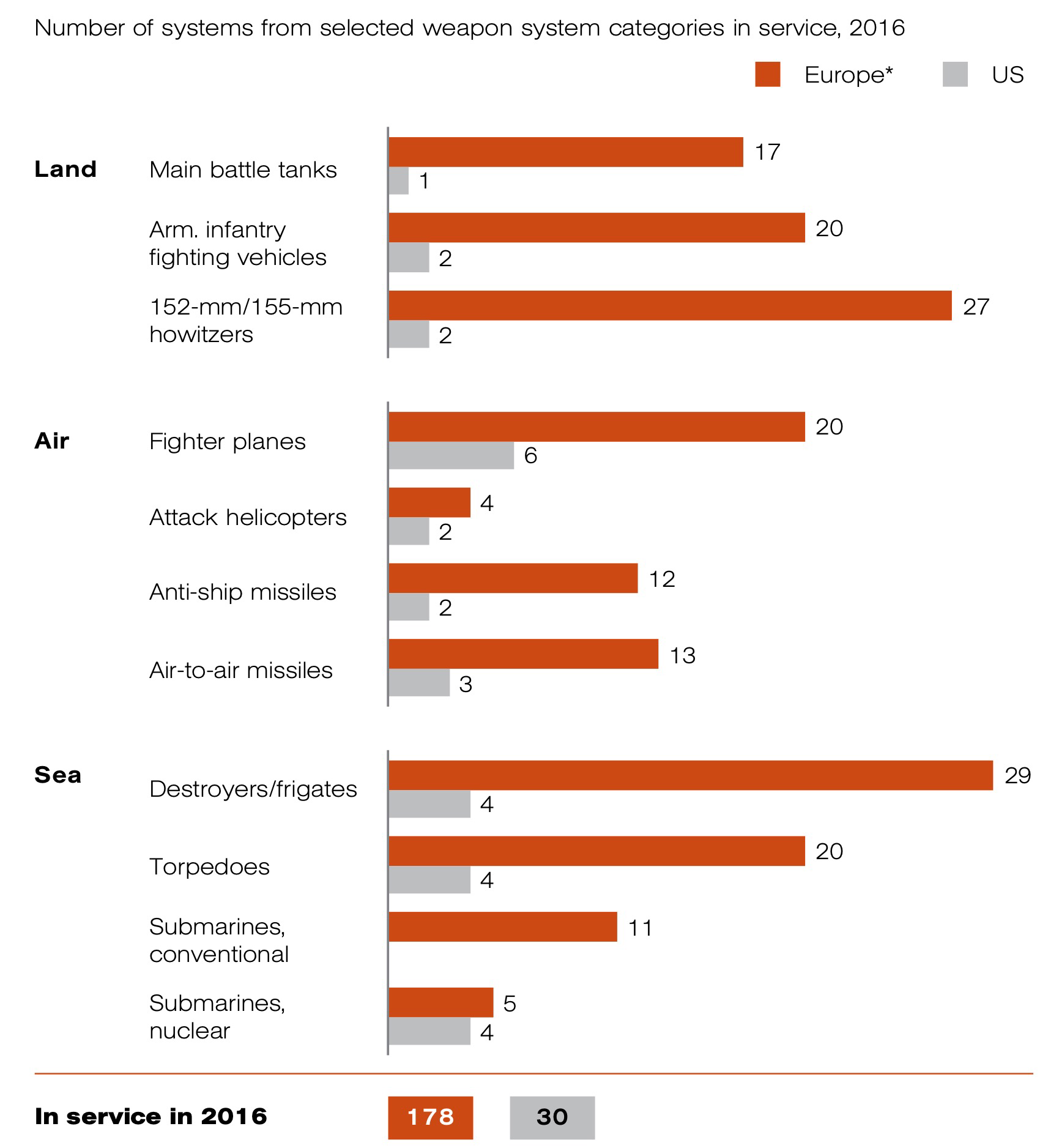

On the European level, the parallel existence of separate national defence forces means that NATO’s European members – despite their supposed miserliness – have about 500,000 more active personnel than the United States. And despite years of seeking enhanced pooling and sharing of capabilities, there is a great deal of fragmentation, duplication and incompatibility between national systems. As the table below shows, Europeans currently use 178 different systems in essential categories compared to just 30 in the US forces.

Graphic provided to MSC by Center for Security Studies (ETH Zurich).

So if European states are going to heed US calls to increase spending, they are going to have to spend much, much smarter. But the next question is: How?

For the European Union, security is high on the agenda. This is true both in terms of the link between migration and terrorism, as well as in terms of security and defence vis-à-vis a resurgent Russia. The EU is particularly important in the latter regard for Sweden and Finland, who are concerned about their eastern flank but remain outside of NATO. However, the momentum for a real leap forward towards integrated EU defence is still not there, even despite the departure of the biggest spoiler of such ambitions, the United Kingdom.

Instead, change will have to come from the patchwork of cooperation that already exists between member states. And in order to gain traction, visible outcomes will be needed on major development and procurement projects, moving beyond the traditional logic of juste retour.

These efforts will naturally revolve around Germany. It has the largest military in Central Europe and is the only one of the big three defence actors focused strongly on territorial defence.

More practical steps towards integration could follow the example of the Dutch, whose army now operates almost exclusively through joint structures with German land forces, with further plans for integrated special navy units and air force capabilities. The initial stages of that model are now also being applied to Polish-German and Czech-German military cooperation.

Should that blueprint be expanded and widened to cover full capabilities, European defence integration could be built from the bottom up. This offers a much more promising avenue of approaching the long term goal of a European pillar than does the classic top-down process of treaty revision.

The US, meanwhile, will likely welcome any model that means increased European spending and capabilities. But what they have not yet realized is that Europe’s readiness to engage in global missions alongside the US is unlikely to grow in tandem with its defence budget.

If and when Europe increases defence co-operation, it will do so with European security priorities in mind. These include territorial integrity, the linkage between external and internal security, and risk control in the periphery of Europe. Most continental Europeans view territorial defence as the core mission of their armed forces. While they accept some force projection in the neighbourhood, most do not believe in the rationale of overseas military intervention.

As such, while properly integrated and expanded European defence structures would be much more effective than the fragmentation that exists today, it might not be quite what America has in mind.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.